Transcriptome and Gene Family Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Channa maculata Larvae in Response to Nanoplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.4. Histopathological Analysis

2.5. Biochemical Analysis

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Differential Expression Analysis

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Validation

2.8. Identification and Characterization of the HNRNP Gene Family

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Analysis

3.2. Enzyme Activity Analysis

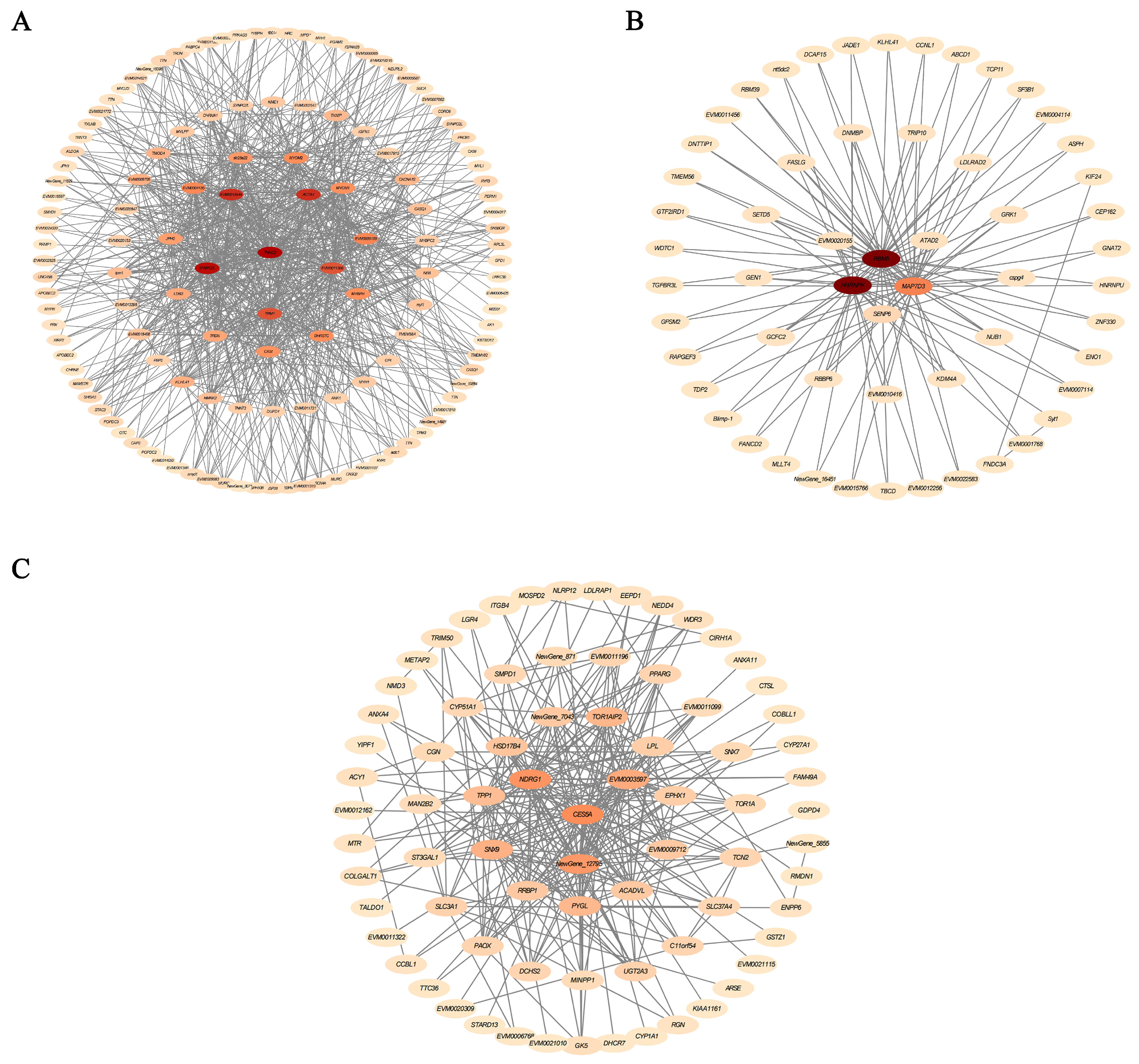

3.3. Transcriptome Analysis

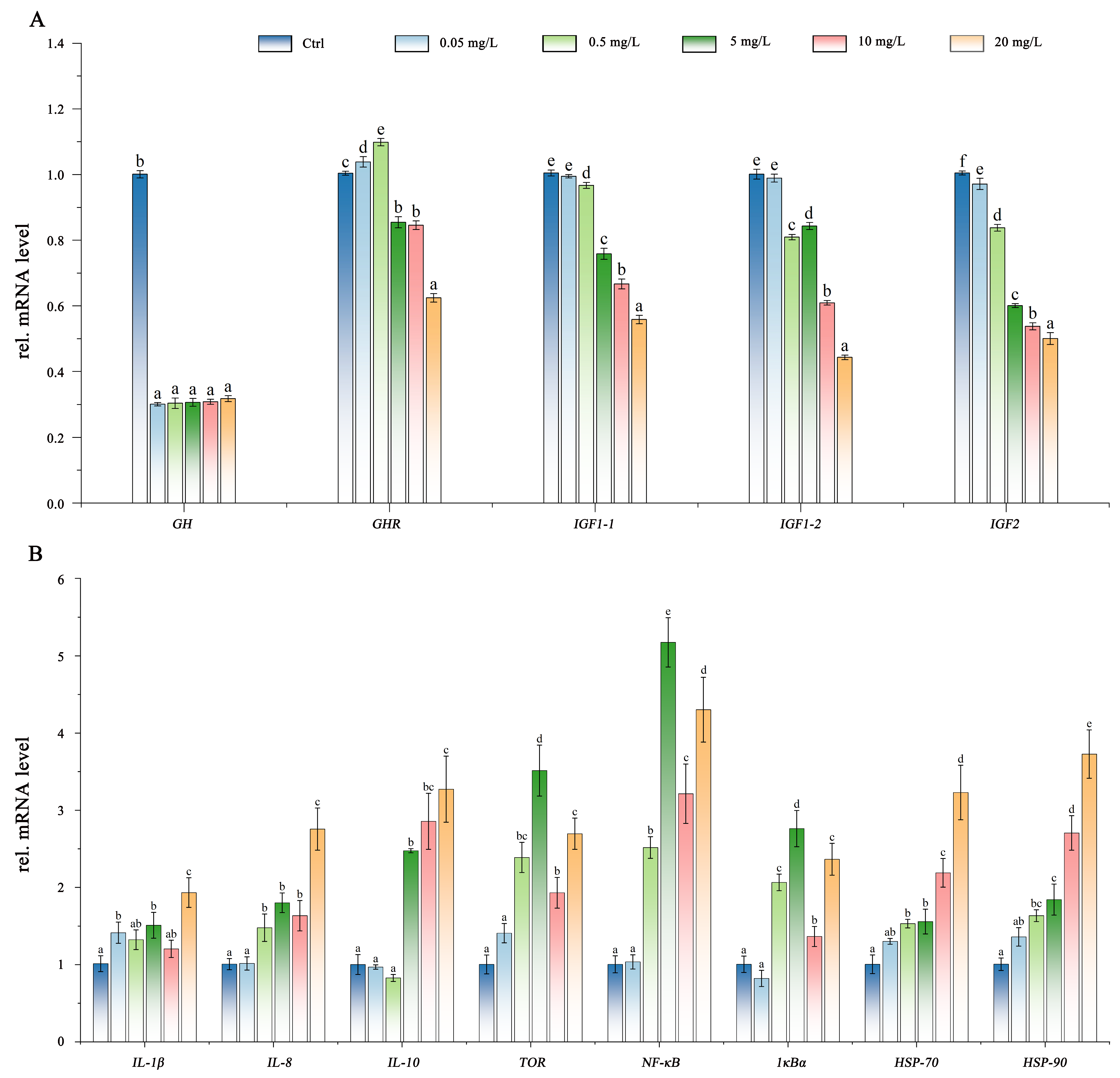

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis

3.5. Analysis of the HNRNP Gene Family

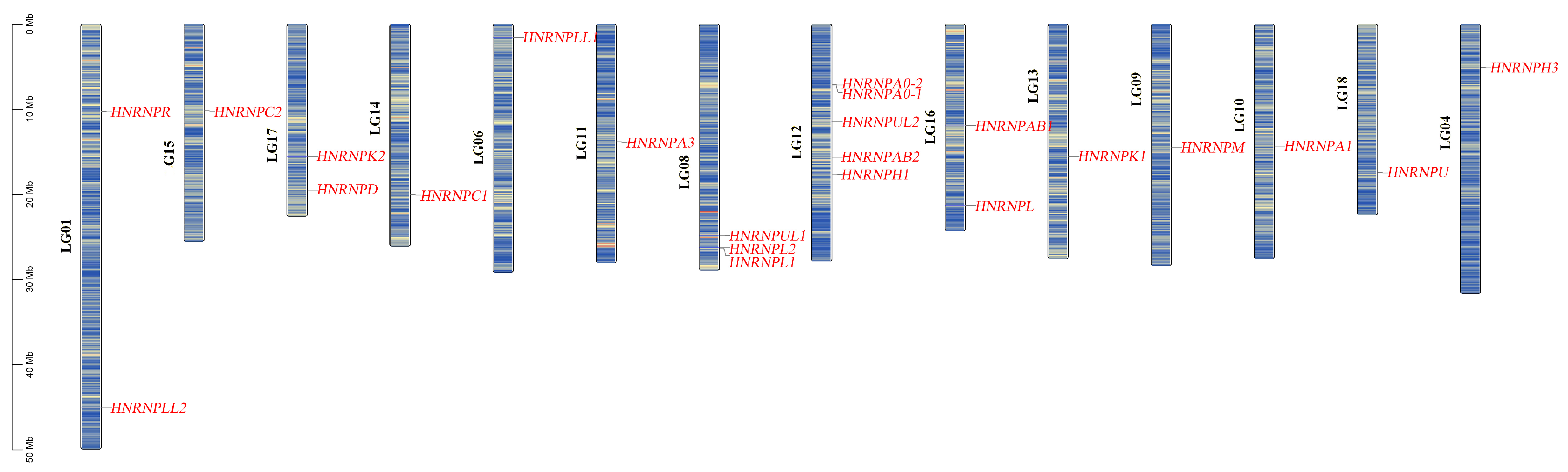

3.5.1. Genomic Distribution and Phylogenetic Classification

3.5.2. Evolutionary Conservation Revealed by Synteny Analysis

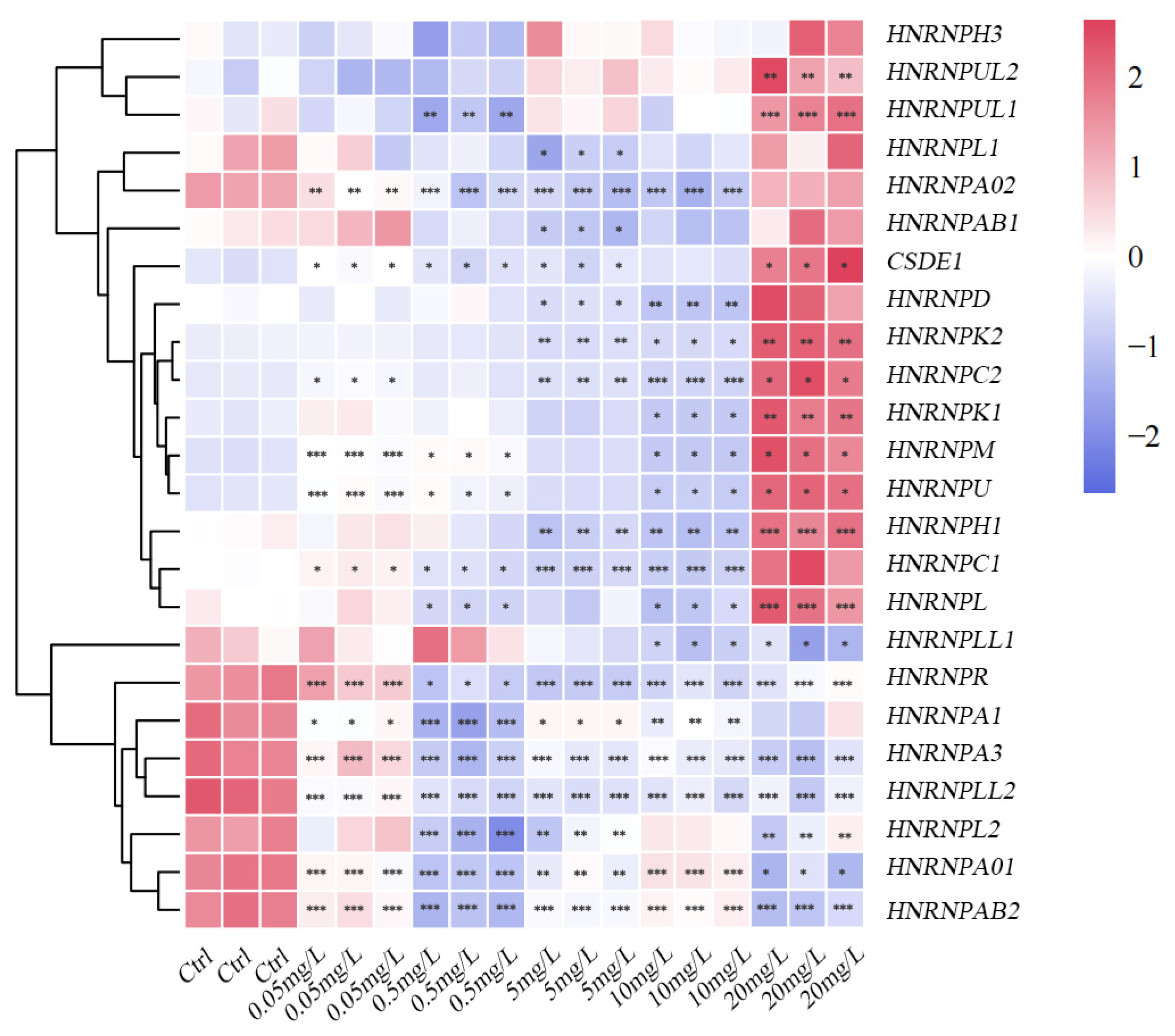

3.5.3. Expression Profiles in Response to PSNPs Exposure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhardwaj, L.K.; Rath, P.; Choudhury, M. A Comprehensive Review on the Classification, Uses, Sources of Nanoparticles (NPs) and Their Toxicity on Health. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2023, 7, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Cowger, W.; Erdle, L.M.; Coffin, S.; Villarrubia-Gómez, P.; Moore, C.J.; Carpenter, E.J.; Day, R.H.; Thiel, M.; Wilcox, C. A Growing Plastic Smog, Now Estimated to Be over 170 Trillion Plastic Particles Afloat in the World’s Oceans—Urgent Solutions Required. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Cao, J.; Yu, F.; Ma, J. Microbial Degradation of Polystyrene Microplastics by a Novel Isolated Bacterium in Aquatic Ecosystem. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 30, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Kelly, F.J.; Wright, S.L. Advances and Challenges of Microplastic Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems: A UK Perspective. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procop, I.; Calmuc, M.; Pessenlehner, S.; Trifu, C.; Ceoromila, A.C.; Calmuc, V.A.; Fetecău, C.; Iticescu, C.; Musat, V.; Liedermann, M. The First Spatio-Temporal Study of the Microplastics and Meso–Macroplastics Transport in the Romanian Danube. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, D.; Kamp, J.; Dierkes, G.; Ternes, T.; Hoffmann, T. Cross-Sectional Distribution of Microplastics in the Rhine River, Germany—A Mass-Based Approach. Microplastics 2025, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujaczek, T.; Kolter, S.; Locky, D.; Ross, M.S. Characterization of Microplastics and Anthropogenic Fibers in Surface Waters of the North Saskatchewan River, Alberta, Canada. FACETS 2021, 6, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Zeng, J.; Chai, L.; Niu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, P.; Yin, Q. Geographical Features and Management Strategies for Microplastic Loads in Freshwater Lakes. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Cao, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; Tong, Y.; Fan, W.; Xie, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, J. Characteristics and Source-Pathway of Microplastics in Freshwater System of China: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 297, 134192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Bai, Q.; Zheng, R.; Li, P.; Liu, R.; Yu, S.; Liu, J. Mass Concentration, Spatial Distribution, and Risk Assessment of Small Microplastics (1–100 Μm) and Nanoplastics (<1 Μm) in the Surface Water of Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moteallemi, A.; Dehghani, M.H.; Momeniha, F.; Azizi, S. Nanoplastics as Emerging Contaminants: A Systematic Review of Analytical Processes, Removal Strategies from Water Environments, Challenges and Perspective. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 111884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Jayasundara, N.; Di Giulio, R. Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments: Impacts on Aquatic Species and Interactions with Environmental Factors and Pollutants. Toxics 2022, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagner, M.; Boudry, G.; Courcot, L.; Vincent, D.; Dehaut, A.; Duflos, G.; Huvet, A.; Tallec, K.; Zambonino-Infante, J.-L. Experimental Evidence That Polystyrene Nanoplastics Cross the Intestinal Barrier of European Seabass. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandts, I.; Cánovas, M.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Llorca, M.; Vega, A.; Farré, M.; Pastor, J.; Roher, N.; Teles, M. Nanoplastics Are Bioaccumulated in Fish Liver and Muscle and Cause DNA Damage After a Chronic Exposure. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, W.-X. Nanoplastics Transport in Zebrafish Brain: Molecular and Phenotypic Behavioral Impacts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, T.; Glassom, D. Decreased Growth and Survival in Small Juvenile Fish, After Chronic Exposure to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Microplastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, F.; Pramata, A.D.; Soegianto, A.; Hu, S.-Y. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Cause Developmental Abnormalities, Oxidative Damage and Immune Toxicity in Early Zebrafish Development. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 295, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.; Soliman, H.A.M.; Badrey, A.E.A.; Osman, A.G.M. Microplastics Induced Histopathological Lesions in Some Tissues of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Early Juveniles. Tissue Cell 2021, 71, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.A.M.; Dehler, C.E.; Król, E. Transcriptomic Responses in the Fish Intestine. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 64, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. Effects of Acute Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoplastics on the Channel Catfish Larvae: Insights from Energy Metabolism and Transcriptomic Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 923278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonta, G.; Mancia, A.; Benkhalqui, A.; Bertolucci, C.; Abelli, L.; Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C. Microplastics Induce Transcriptional Changes, Immune Response and Behavioral Alterations in Adult Zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Dai, J.; Tong, J.; Jin, G. Transcriptome Sequencing and Metabolite Analysis Reveal the Toxic Effects of Nanoplastics on Tilapia After Exposure to Polystyrene. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotello, F.; Di Camillo, B. Measuring Differential Gene Expression with RNA-Seq: Challenges and Strategies for Data Analysis. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2015, 14, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, P.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Ten Years of Pathway Analysis: Current Approaches and Outstanding Challenges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ji, F.; Jiang, S.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Q. Scale Development-Related Genes Identified by Transcriptome Analysis. Fishes 2022, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.A.H.; Sidiq, M.J.; Altinok, I. Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Fish Health and Reproduction. Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Guo, H.-Y.; Liu, B.-S.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, K.-C.; Xian, L.; Zhao, P.-H.; Yang, H.-Y.; Zhang, D.-C. Genome-Wide Identification of Heat Shock Protein Gene Family and Their Responses to Pathogen Challenge in Trachinotus ovatus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 145, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, X.; Chang, M.; Tian, Q.; He, Z.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, D.; Yan, T. Toll-like Receptor-4 in the Fish Immune System. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 169, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Qiu, S.; Li, Y.; Fu, T.; Yu, J.; Ma, K.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, C. Heat Shock Proteins Gene Family: Genome-Wide Identification in Micropterus salmoides and Expression Analysis under High-Temperature Stress. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 43, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasauer, S.M.K.; Neuhauss, S.C.F. Whole-Genome Duplication in Teleost Fishes and Its Evolutionary Consequences. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yu, H.; Xue, N.; Bao, H.; Gao, Q.; Tian, Y. Alternative Splicing Patterns of Hnrnp Genes in Gill Tissues of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) During Salinity Changes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 271, 110948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Wang, F.; Li, K.; Wu, Y.; Huang, S.; Luo, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Fei, S.; Chen, K.; et al. Generation of Myostatin Gene-Edited Blotched Snakehead (Channa maculata) Using CRISPR/Cas9 System. Aquaculture 2023, 563, 738988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Deng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Luo, Q.; Fei, S.; et al. Single and Combined Effects of Polystyrene Nanoplastics and Dibutyl Phthalate on Hybrid Snakehead (Channa maculata ♀ × Channa argus ♂). Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, H.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xi, D. Toxicological Effects and Molecular Metabolic of Polystyrene Nanoplastics on Soybean (Glycine max L.): Strengthening Defense Ability by Enhancing Secondary Metabolisms. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q.; Zou, J.; Zhu, J. Species-Specific Effects of Microplastics on Juvenile Fishes. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1256005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Huang, R.; Yang, C.; Gui, B.; Luo, Q.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Chromosome-Level Genome Assemblies of Channa argus and Channa maculata and Comparative Analysis of Their Temperature Adaptability. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.C.; Geleta, B.; Maleki, S.; Richardson, D.R.; Kovačević, Ž. The Metastasis Suppressor NDRG1 Directly Regulates Androgen Receptor Signaling in Prostate Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geuens, T.; Bouhy, D.; Timmerman, V. The hnRNP Family: Insights into Their Role in Health and Disease. Hum. Genet. 2016, 135, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.A.; Kozal, J.S.; Jayasundara, N.; Massarsky, A.; Trevisan, R.; Geitner, N.; Wiesner, M.; Levin, E.D.; Di Giulio, R.T. Uptake, Tissue Distribution, and Toxicity of Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 194, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wu, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Fu, Z.; Shi, H.; Raley-Susman, K.M.; He, D. Microplastic Particles Cause Intestinal Damage and Other Adverse Effects in Zebrafish Danio rerio and Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pomeren, M.; Brun, N.R.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Vijver, M.G. Exploring Uptake and Biodistribution of Polystyrene (Nano)Particles in Zebrafish Embryos at Different Developmental Stages. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 190, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, M.; Xu, C.; Zou, X.; Xia, Z.; Su, L.; Qiu, N.; Cai, L.; Yu, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Microplastics Induces Intestinal Function Dysbiosis in Rare Minnow (Gobiocypris rarus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa Araújo, A.P.; De Melo, N.F.S.; De Oliveira Junior, A.G.; Rodrigues, F.P.; Fernandes, T.; De Andrade Vieira, J.E.; Rocha, T.L.; Malafaia, G. How Much Are Microplastics Harmful to the Health of Amphibians? A Study with Pristine Polyethylene Microplastics and Physalaemus cuvieri. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 382, 121066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, A.; Ye, Q.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, G.; Zou, J. Species-Specific Effect of Microplastics on Fish Embryos and Observation of Toxicity Kinetics in Larvae. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatelli, G.; Furlan, A.; Calandra, A.; Dioguardi Burgio, M. Hepatic Sinusoidal Dilatation. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 2011–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-M.; Byeon, E.; Jeong, H.; Kim, M.-S.; Chen, Q.; Lee, J.-S. Different Effects of Nano- and Microplastics on Oxidative Status and Gut Microbiota in the Marine Medaka (Oryzias melastigma). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Liu, S.; Junaid, M.; Gao, D.; Ai, W.; Chen, G.; Wang, J. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exacerbated the toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics through histological damage and intestinal microbiota dysbiosis in freshwater Micropterus salmoides. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.; Le, M.; Hazemi, M.; Biales, A.; Bencic, D.C.; Blackwell, B.R.; Bush, K.; Flick, R.; Hoang, J.X.; Martinson, J.; et al. Comparing Transcriptomic Points of Departure to Apical Effect Concentrations For Larval Fathead Minnow Exposed to Chemicals with Four Different Modes of Action. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 86, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, X.; Company, J.J.; Alomar, C.; Compa, M.; Sureda, A.; Grau, A.; Hansjosten, B.; López-Vázquez, J.; Quintana, J.B.; Rodil, R.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Virgin and Seawater Exposed Microplastic Enriched-Diet Causes Liver Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Gilthead Seabream Sparus aurata, Linnaeus 1758. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iheanacho, S.C.; Odo, G.E. Dietary Exposure to Polyvinyl Chloride Microparticles Induced Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Damage in Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21159–21173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Fang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, C. Adverse Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics in the Freshwater Commercial Fish, Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): Emphasis on Physiological Response and Intestinal Microbiome. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Yao, X.; Yan, X.; Peng, R. Environmental Nanoplastics Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Review of Cellular Mechanisms and Associated Diseases. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.A.; Diniz, Y.S.; Marques, S.F.G.; Faine, L.A.; Ribas, B.O.; Burneiko, R.C.; Novelli, E.L.B. The Use of the Oxidative Stress Responses as Biomarkers in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Exposed to in Vivo Cadmium Contamination. Environ. Int. 2002, 27, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, M.; Dai, L.; Cao, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y. Polystyrene Nanoplastic Exposure Induces Developmental Toxicity by Activating the Oxidative Stress Response and Base Excision Repair Pathway in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). ACS Omega 2022, 7, 32153–32163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Addotey, T.N.A.; Chen, J.; Xu, G. Effect of Polystyrene Microplastics on the Antioxidant System and Immune Response in GIFT (Oreochromis niloticus). Biology 2023, 12, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T. Microplastics Bioaccumulation in Fish: Its Potential Toxic Effects on Hematology, Immune Response, Neurotoxicity, Oxidative Stress, Growth, and Reproductive Dysfunction. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, W.; Ru, S. Polystyrene Microplastics Cause Tissue Damages, Sex-Specific Reproductive Disruption and Transgenerational Effects in Marine Medaka (Oryzias melastigma). Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Geng, J. Toxicological Effects of Nano- and Micro-Polystyrene Plastics on Red Tilapia: Are Larger Plastic Particles More Harmless? J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 396, 122693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piano, F.; Lama, A.; Piccolo, G.; Addeo, N.F.; Iaccarino, D.; Fusco, G.; Riccio, L.; De Biase, D.; Mattace Raso, G.; Meli, R.; et al. Impact of Polystyrene Microplastic Exposure on Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata linnaeus, 1758): Differential Inflammatory and Immune Response Between Anterior and Posterior Intestine. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, B. Size-Specific Effects of Microplastics and Lead on Zebrafish. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 139383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, H.; Cong, Z.; Zhao, L.-H.; Zhou, Q.; Mao, C.; Cheng, X.; Shen, D.-D.; Cai, X.; Ma, C.; et al. Structural Basis for Activation of the Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone Receptor. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Bian, C.; Ji, H.; Ji, S.; Sun, J. DHA Induces Adipocyte Lipolysis Through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the cAMP/PKA Signaling Pathway in Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Anim. Nutr. 2023, 13, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, H.-J.; Chang, C.-Y.; Ho, H.-P.; Chou, M.-Y. Oxytocin Signaling Acts as a Marker for Environmental Stressors in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, N.; Body-Malapel, M. Immunotoxicity and Intestinal Effects of Nano- and Microplastics: A Review of the Literature. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, L.-B.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Zheng, J.-L. Combined Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics and Cadmium on Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and GH/IGF Axis in Zebrafish Early Life Stages. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-L.; Chen, X.; Peng, L.-B.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Li, J.; Han, T. Particles Rather than Released Zn2+ from ZnO Nanoparticles Aggravate Microplastics Toxicity in Early Stages of Exposed Zebrafish and Their Unexposed Offspring. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Yao, L.; Pan, L. Gene Expression and Functional Analysis of Different Heat Shock Protein (HSPs) in Ruditapes Philippinarum Under BaP Stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 251, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, B.P.; Mahanty, A.; Mitra, T.; Parija, S.C.; Mohanty, S. Heat Shock Proteins in Stress in Teleosts. In Regulation of Heat Shock Protein Responses; Heat Shock Proteins; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 13, pp. 71–94. ISBN 978-3-319-74714-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Shadi, A. Combined Effects of Microplastics and Benzo[a]Pyrene on Asian Sea Bass Lates calcarifer Growth and Expression of Functional Genes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 283, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.; Xu, S.; Cui, J.; Li, K.; Shiwen, X.; Guo, M. Polystyrene Microplastics Induce Myocardial Inflammation and Cell Death via the TLR4/NF-κB Pathway in Carp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 135, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.L.; Bera, A.; Wong, F.K.; Lewis, S.M. Cellular Stress Orchestrates the Localization of hnRNP H to Stress Granules. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 394, 112111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.J.; Zhu, Z.X.; Qin, H.; Meng, Z.N.; Lin, H.R.; Xia, J.H. Genome-Wide Characterization of Alternative Splicing Events and Their Responses to Cold Stress in Tilapia. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.S.; Hightower, R.M.; Reid, A.L.; Bennett, A.H.; Iyer, L.; Slonim, D.K.; Saha, M.; Kawahara, G.; Kunkel, L.M.; Kopin, A.S.; et al. hnRNP L Is Essential for Myogenic Differentiation and Modulates Myotonic Dystrophy Pathologies. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maceratessi, S.; Sampaio, N.G. hnRNPs in Antiviral Innate Immunity. Immunology 2024, 173, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cen, J.; Wu, H.; Gao, W.; Jia, Z.; Adamek, M.; Zou, J. Autophagy Mediated Degradation of MITA/TBK1/IRF3 by a hnRNP Family Member Attenuates Interferon Production in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 149, 109563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Cheng, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Leader RNA Facilitates Snakehead Vesiculovirus (SHVV) Replication by Interacting with CSDE1 and hnRNP A3. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.-Q.; Qin, X.; Wu, H.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.-A.; Tu, J. hnRNPA1 Impedes Snakehead Vesiculovirus Replication via Competitively Disrupting Viral Phosphoprotein-Nucleoprotein Interaction and Degrading Viral Phosphoprotein. Virulence 2023, 14, 2196847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Gao, D.; Lu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, L.; Luo, Q.; Liu, H.; Fei, S.; Chen, K.; et al. Transcriptome and Gene Family Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Channa maculata Larvae in Response to Nanoplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010125

Yang Z, Gao D, Lu Y, Zou Y, Deng Y, Liu L, Luo Q, Liu H, Fei S, Chen K, et al. Transcriptome and Gene Family Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Channa maculata Larvae in Response to Nanoplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ziwen, Dandan Gao, Yuntao Lu, Yang Zou, Yueying Deng, Luping Liu, Qing Luo, Haiyang Liu, Shuzhan Fei, Kunci Chen, and et al. 2026. "Transcriptome and Gene Family Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Channa maculata Larvae in Response to Nanoplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010125

APA StyleYang, Z., Gao, D., Lu, Y., Zou, Y., Deng, Y., Liu, L., Luo, Q., Liu, H., Fei, S., Chen, K., Zhao, J., & Ou, M. (2026). Transcriptome and Gene Family Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Channa maculata Larvae in Response to Nanoplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants, 15(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010125