Temporal Dynamics of Perioperative Redox Balance and Its Association with Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

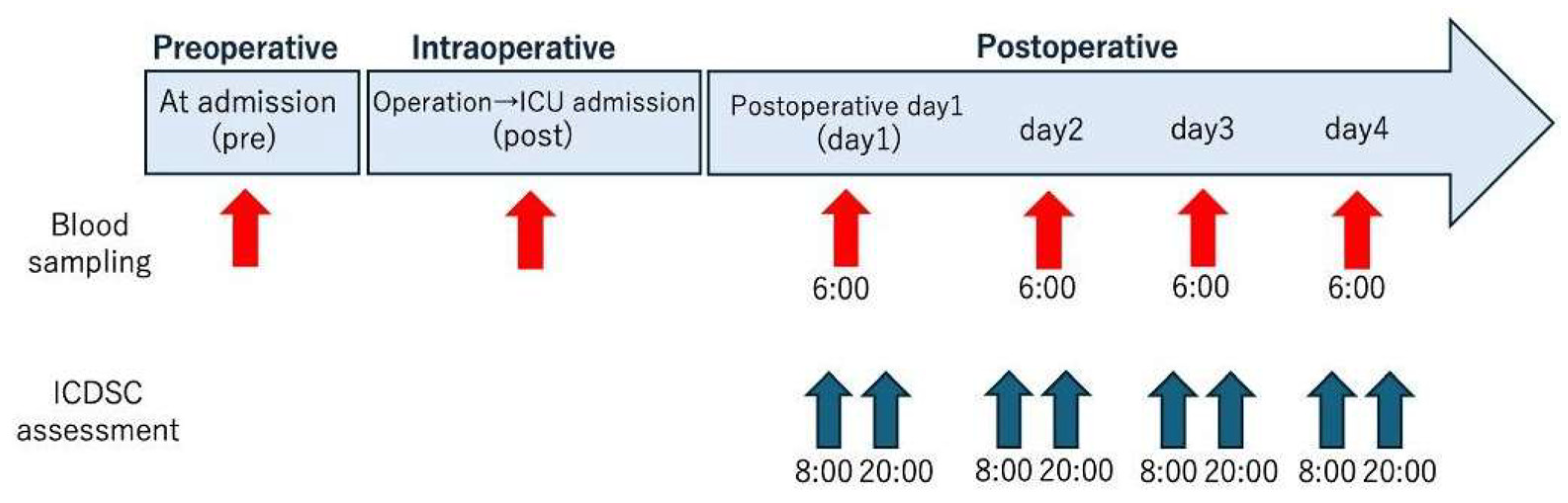

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Blood Analysis

2.4. POD Assessment

2.5. Study Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

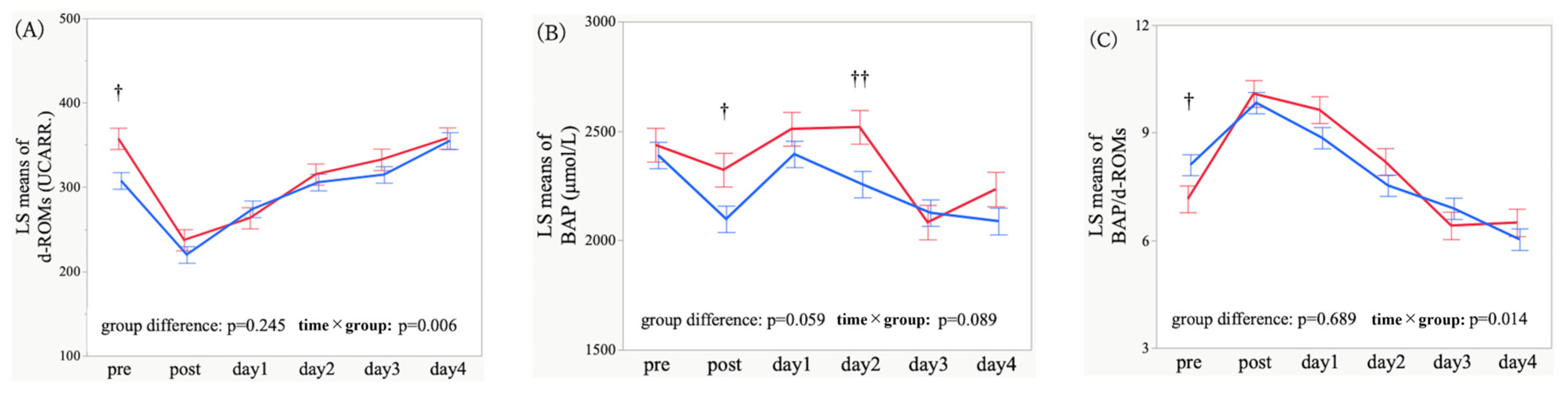

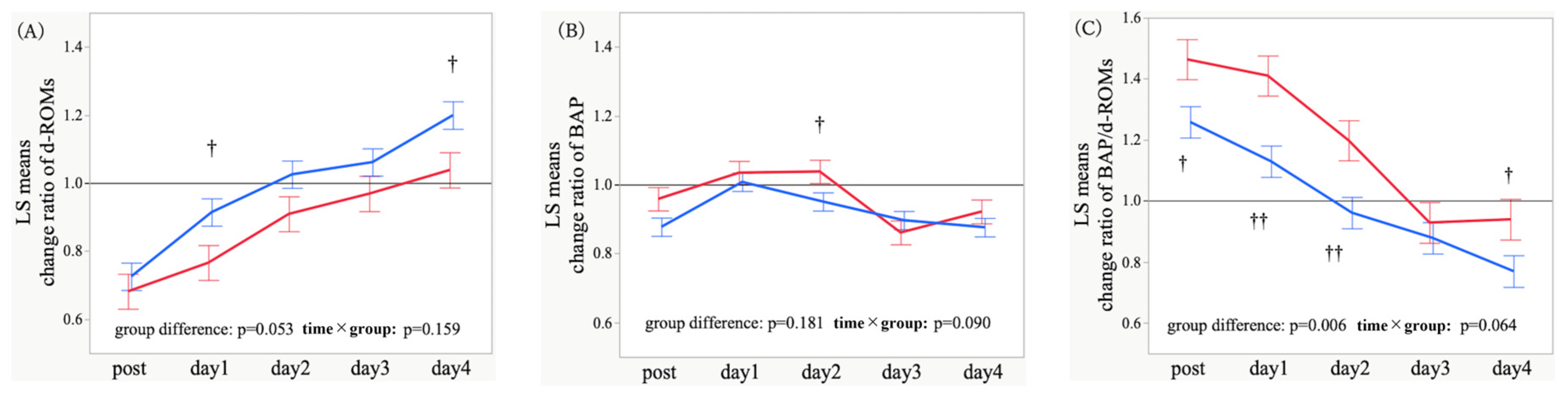

3.2. Temporal Trajectories and Time-Point Comparisons of Oxidative Stress Markers

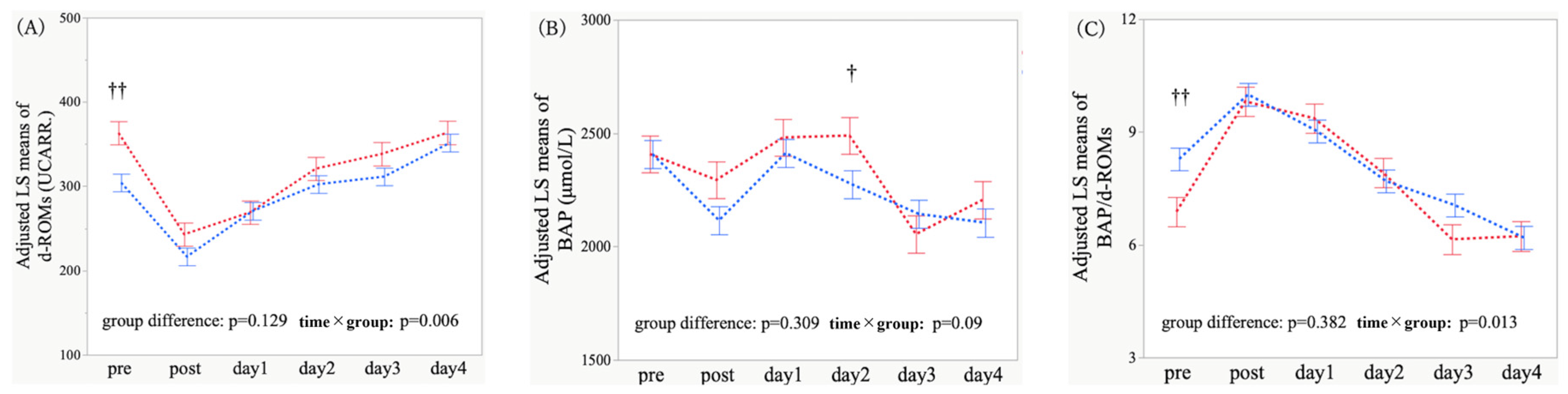

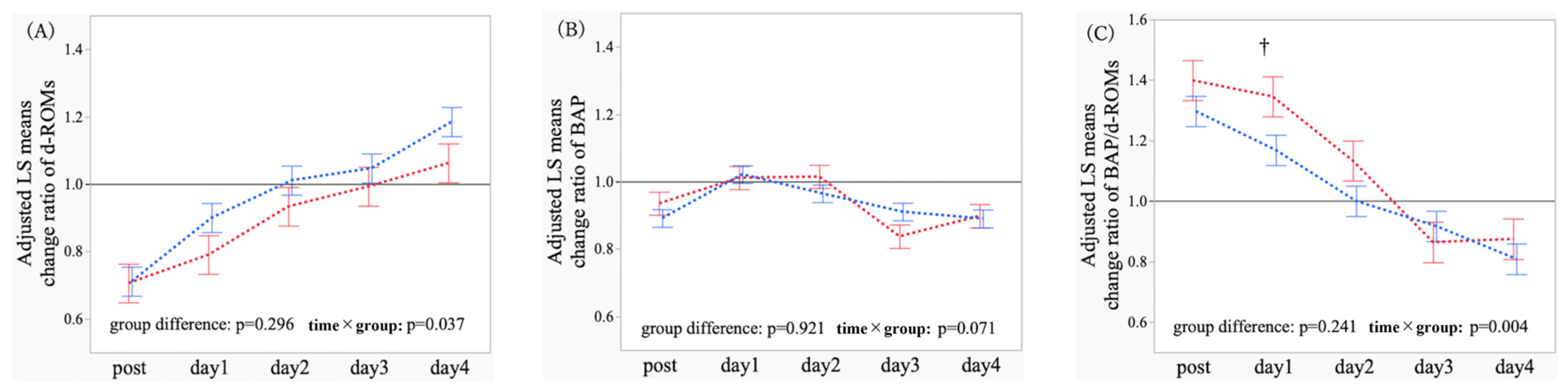

3.3. Adjusted Temporal Trajectories and Time-Point Comparisons of Oxidative Stress Markers

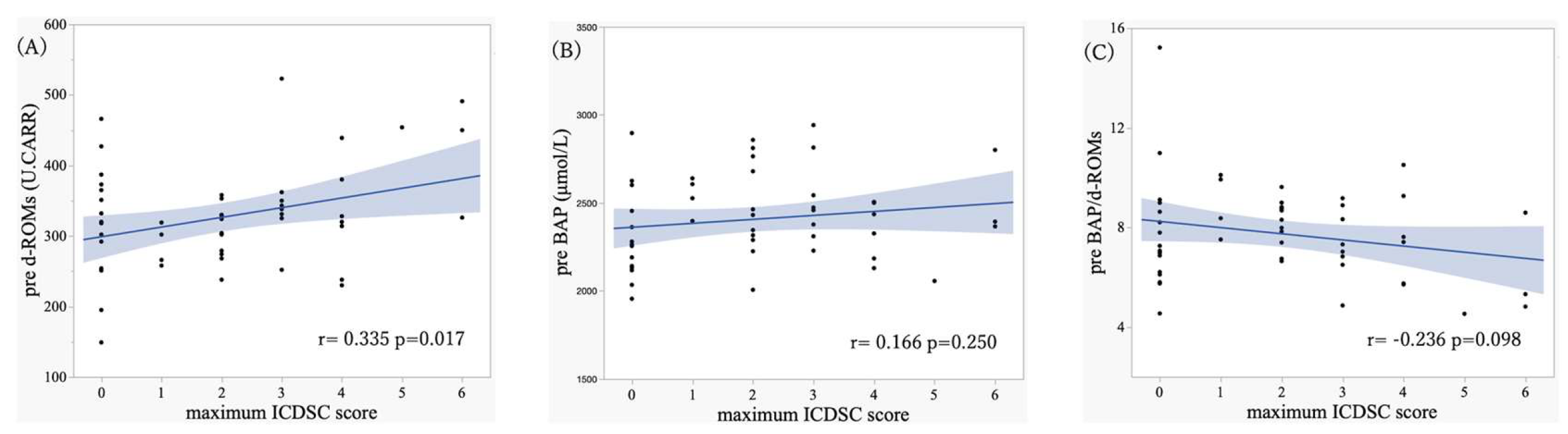

3.4. Association Between Oxidative Stress Markers and ICDSC Scores

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Secondary and Subgroup Analyses

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAP | Biological antioxidant potential |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| d-ROMs | Derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites |

| ICDSC | Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist |

| LS | Least-squares |

| MMRM | Mixed-effects model for repeated measures |

| POD | Postoperative delirium |

| RASS | Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale |

| SE | Standard error |

References

- Evered, L.; Silbert, B.; Knopman, D.S.; Scott, D.A.; DeKosky, S.T.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Oh, E.S.; Crosby, G.; Berger, M.; Eckenhoff, R.G. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery—2018. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, T.G.; Weldon, B.C.; Garvan, C.W.; Dede, D.E.; van der Aa, M.T.; Heilman, K.M.; Gravenstein, J.S. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2008, 108, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachter, R.M. Understanding Patient Safety, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National Quality Clearinghouse Measure: Delirium—Proportion of Patients Meeting Diagnostic Criteria on CAM; AHRQ: Rockville, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle, P.G.; MacLean, C.H.; Morton, S.C.; Wenger, N.S. ACOVE quality indicators. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 135, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Kotfis, K.; Hosie, A.; MacLullich, A.M.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Ely, E.W.; Pun, B.T. Delirium monitoring: Yes or no? That is the question. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lee, M.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Jeong, S.Y. Effects of nonpharmacological interventions on sleep improvement and delirium prevention in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, E.W.; Shintani, A.; Truman, B.; Speroff, T.; Gordon, S.M.; Harrell, F.E.; Inouye, S.K.; Bernard, G.R.; Dittus, R.S. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004, 291, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.H.; Laflam, A.; Max, L.; Lymar, D.; Neufeld, K.J.; Tian, J.; Shah, A.S.; Whitman, G.; Hogue, C.W. Cognitive decline after delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C.N.; Starke-Reed, P.E.; Stadtman, E.R.; Liu, G.J.; Carney, J.M.; Floyd, R.A. Oxidative damage to brain proteins during ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 5144–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.G.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Morse, J.; Shotwell, M.S.; Milne, G.L.; Pretorius, M.; Shaw, A.D.; Roberts, L.J.; Billings, F.T. Intraoperative cerebral oxygenation, oxidative injury, and delirium. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 103, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantke, U.; Volk, T.; Schmutzler, M.; Loop, T.; Geiger, K.; Pahl, H.L. Oxidized proteins as a marker of oxidative stress during coronary heart surgery. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquini, A.; Luchetti, E.; Marchetti, V.; Cardini, G.; Iorio, E.L. Analytical performances of d-ROMs test and BAP test in canine plasma. Vet. Res. Commun. 2008, 32, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesarone, M.R.; Belcaro, G.; Carratelli, M.; Cornelli, U.; De Sanctis, M.T.; Incandela, L.; Barsotti, A.; Terranova, R.; Nicolaides, A.N. A simple test to monitor oxidative stress. Int. Angiol. 1999, 18, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trotti, R.; Carratelli, M.; Barbieri, M. A new method for detection of hydroperoxides in serum. Panminerva Med. 2002, 44, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Atabek, M.E.; Keskin, M.; Yazici, C.; Kendirci, M.; Hatipoglu, N.; Koklu, E.; Kurtoglu, S. Oxidative stress in childhood obesity. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 17, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamezaki, F.; Sonoda, S.; Tomiyama, H.; Yamashina, A.; Ohya, Y.; Nakashima, Y. Derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites correlate with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in a Japanese population. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2008, 15, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, H.; Kawabe, H.; Komiya, N.; Saito, I. Relationships between serum reactive oxygen metabolites (ROMs) and metabolic parameters in patients with lifestyle-related diseases. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2009, 16, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Saito, H.; Yoshida, T.; Nishino, H. Oxidative stress and atherosclerotic changes in retinal arteries in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. J. 2008, 55, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrano, V.; Lenti, M.; Sanesi, M.; Cocci, F.; Papa, A.; Zucchelli, G.C. A new method to evaluate oxidative stress in humans. Immunoanal. Biol. Specim. 2002, 17, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regano, N.; Ceravolo, R.; Caroleo, M.C.; Foti, D.; Gallelli, L.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Iorio, E.L. Assessment of oxidative stress in clinical practice: Evaluation of d-ROMs and BAP tests in metabolic disorders. Nutr. Ther. Metab. 2008, 26, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Tsuda, Y.; Kitaoka, T.; Kyotani, S. Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity in healthy children using d-ROMs and BAP tests. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2019, 82, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzzone, M.J.; Hornung, R.; Weibel, S.; Spies, C.D.; Berger, M. Electroencephalographic measures of delirium in the perioperative setting: A systematic review. Anesth. Analg. 2025, 140, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boettger, S.; Meyer, R.; Richter, C.; Henschel, J.; Bär, K.J. Screening for delirium with the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC): A validation study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2018, 148, w14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Mo, L.; Hu, H.; Ou, Y.; Luo, J. Risk factors of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress, and the biology of ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucerius, J.; Gummert, J.F.; Borger, M.A.; Walther, T.; Doll, N.; Falk, V.; Schmitt, D.V.; Mohr, F.W. Predictors of delirium after cardiac surgery: Effect of off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 127, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-la-Asunción, J.; Bruno, L.; Perez-Griera, J.; Morcillo, E.; Gallego, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Belda, F.J. Oxidative stress injury after on-pump cardiac surgery: Role of intraoperative antioxidant administration. Redox Rep. 2013, 18, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, R.; González, J.; Paoletto, F. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of hypertension. World J. Cardiol. 2011, 3, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, Y.C.; Ainslie, P.N. Blood pressure regulation IX: Cerebral autoregulation under blood pressure challenges. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Kawamoto, M.; Watanabe, S.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, T. Ascorbic acid attenuates postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierski, J.; Szylińska, A.; Żukowski, M.; Kaliszewska, A.; Jaźwińska-Tarnawska, E.; Kowalski, M.; Madziarska, K.; Sobów, T.; Macherzyńska, B.; Jasiński, M.; et al. Antioxidant capacity as a biomarker of delirium after cardiac surgery. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Xu, Z.; Huang, J.; Nair, S.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Sun, J. Reductive stress causes pathological cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 1293–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloret, A.; Fuchsberger, T.; Giraldo, E.; Viña, J. Reductive stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Guo, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Netrin-1 improves postoperative delirium-like behavior in aged mice through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 14, 751570. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Scopolamine causes delirium-like brain dysfunction via cholinergic and oxidative pathways. Zool. Res. 2023, 44, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative eustress and oxidative distress: On redox homeostasis and signalling. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P. Redox theory of aging: Implications for health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.L.; Jia, L.; Feelisch, M.; Martin, D.S. Perioperative oxidative stress: The unseen enemy. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.R.; Kim, B.S.; Sahoo, S.; Maestre, G.; Moore, R.C. Biomarkers of delirium risk in older adults: A meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab282. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report 2017–2018; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2018.

- Huang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M. Association between C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and postoperative delirium: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 8909–8920. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X. Emerging biomarkers of postoperative delirium: A systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1632947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, J. Effects of anesthetic depth on postoperative pain and delirium in elderly surgical patients: A randomized controlled trial. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, H. Predictive value of CAM-ICU and ICDSC for postoperative delirium: A meta-analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2024, 29, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucerius, J.; Gummert, J.F.; Borger, M.A.; Walther, T.; Doll, N.; Falk, V.; Mohr, F.W. Predictors of delirium after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 127, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Hudetz, J.A.; Patterson, K.M.; Byrne, A.J.; Warltier, D.C.; Pagel, P.S. Postoperative delirium and short-term cognitive dysfunction in patients after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2011, 25, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matata, B.M.; Galiñanes, M. Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting reduces oxidative stress and inflammation compared to conventional surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000, 69, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukićević, P.; Milojević, P.; Marinković, M.; Ivanović, B.; Vasiljević, J. Oxidative stress in on-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Medicina 2021, 57, 763. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hafez, M.F.; El-Masry, A.; Gohar, A.; Sayed, M. Oxidative stress biomarkers in minimally invasive versus off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Egypt. J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

| POD (n = 18) | No POD (n = 32) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 75.6 ± 6.7 | 69.3 ± 11.6 | 0.019 |

| Sex (Male), n (%) | 10 (55.5%) | 18 (56.5%) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.2 ± 3.9 | 22.4 ± 4.1 | 0.312 |

| Smoking(ever), n (%) | 4 (22.2%) | 15 (46.8%) | 0.130 |

| Daily drinking, n (%) | 2 (11.1%) | 5 (18.8%) | 1.000 |

| Baseline oxidative stress markers | |||

| pre d-ROMs (U.CARR) | 352.4 ± 80.6 | 312.1 ± 67.6 | 0.082 |

| pre BAP (µmol/L) | 2438.8 ± 234.4 | 2389.7 ± 254.0 | 0.495 |

| pre BAP/d-ROMs | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 0.188 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (22.2%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.436 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (72.2%) | 12 (37.5%) | 0.038 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (18.8%) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 7 (38.9%) | 7 (21.9%) | 0.325 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 4 (22.2%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.436 |

| Procedure characteristics | |||

| Type of operation, n (%) | |||

| CABG | 2 (11.1%) | 5 (15.6%) | 0.157 |

| Aortic Surgery | 10 (55.6%) | 9 (28.1%) | |

| Valve Surgery | 6 (33.3%) | 18 (56.3%) | |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | |||

| MICS | 6 (33.3%) | 15 (46.9%) | 0.388 |

| MS | 12 (66.7%) | 17 (53.1%) | |

| Operative time (min) | 373 ± 153.3 | 260.1 ± 74.0 | <0.001 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 477.9 ± 161.7 | 353.1 ± 75.6 | <0.001 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) | 212.5 ± 84.4 | 154.2 ± 45.6 | 0.002 |

| Total blood product transfusion (mL) | 3692.6 ± 2754.9 | 2110.8 ± 1620.1 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arai, Y.; Koyama, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Shimada, S.; Yoshida, T. Temporal Dynamics of Perioperative Redox Balance and Its Association with Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010108

Arai Y, Koyama Y, Takahashi A, Shimada S, Yoshida T. Temporal Dynamics of Perioperative Redox Balance and Its Association with Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleArai, Yukiko, Yoshihisa Koyama, Ayako Takahashi, Shoichi Shimada, and Takeshi Yoshida. 2026. "Temporal Dynamics of Perioperative Redox Balance and Its Association with Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010108

APA StyleArai, Y., Koyama, Y., Takahashi, A., Shimada, S., & Yoshida, T. (2026). Temporal Dynamics of Perioperative Redox Balance and Its Association with Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery. Antioxidants, 15(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010108