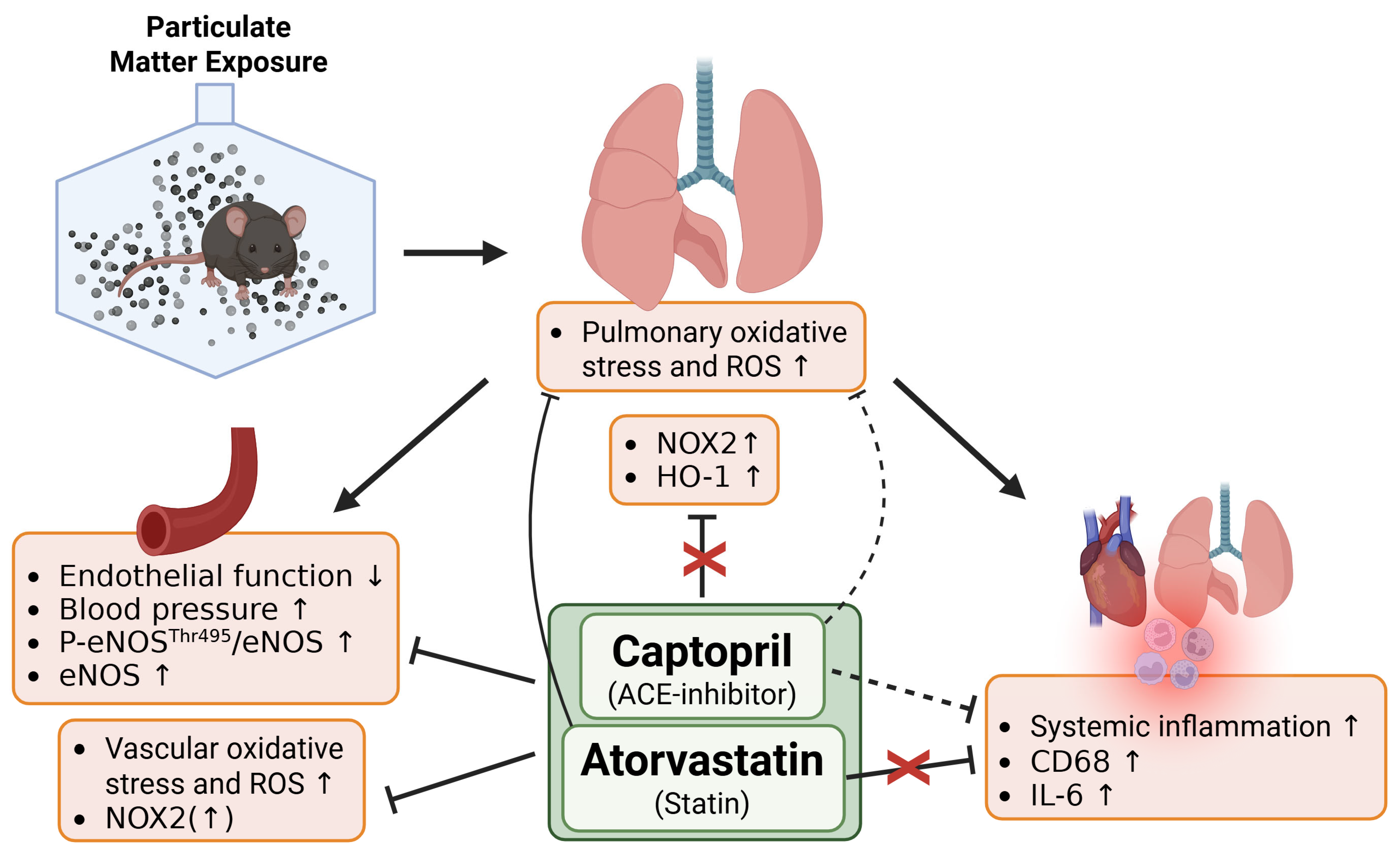

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Statins Mitigate Negative Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Effects of Particulate Matter in a Mouse Exposure Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exposure of Laboratory Animals

2.2. Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measurement

2.3. Isometric Tension Studies in Isolated Aortic Rings

2.4. Dihydroethidium Fluorescence Microtopography

2.5. Western Blot and Dot Blot Analysis

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.7. Statistics

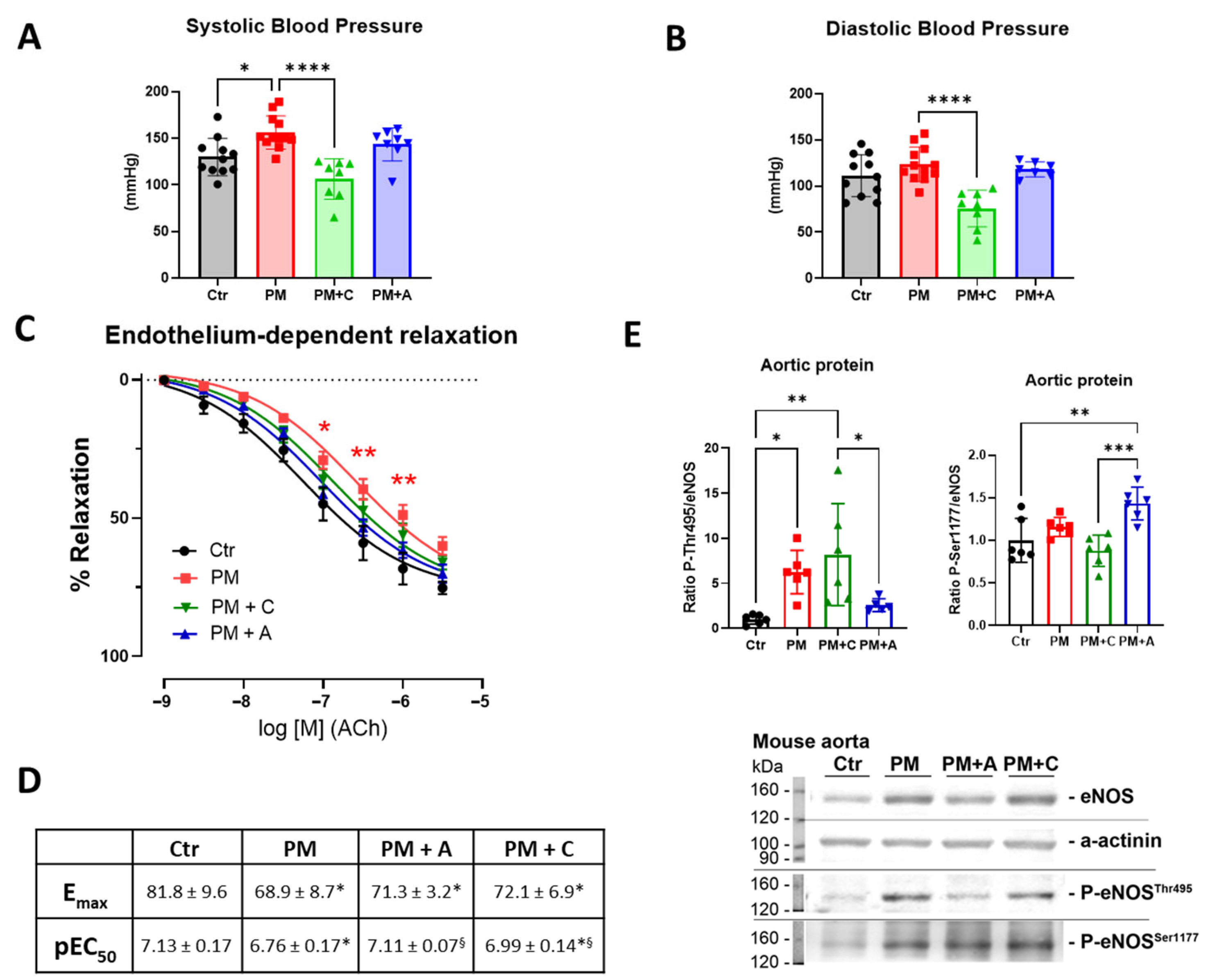

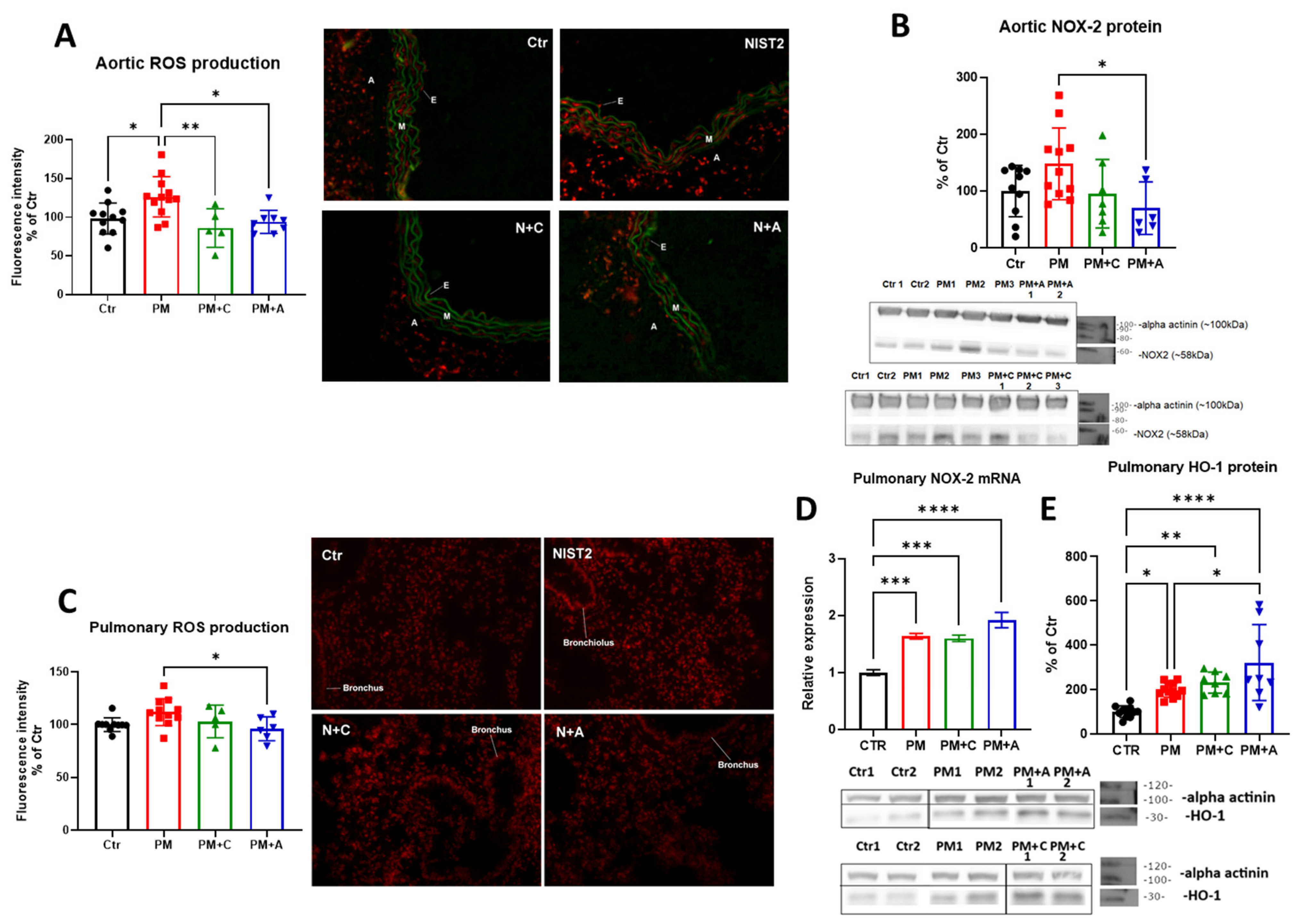

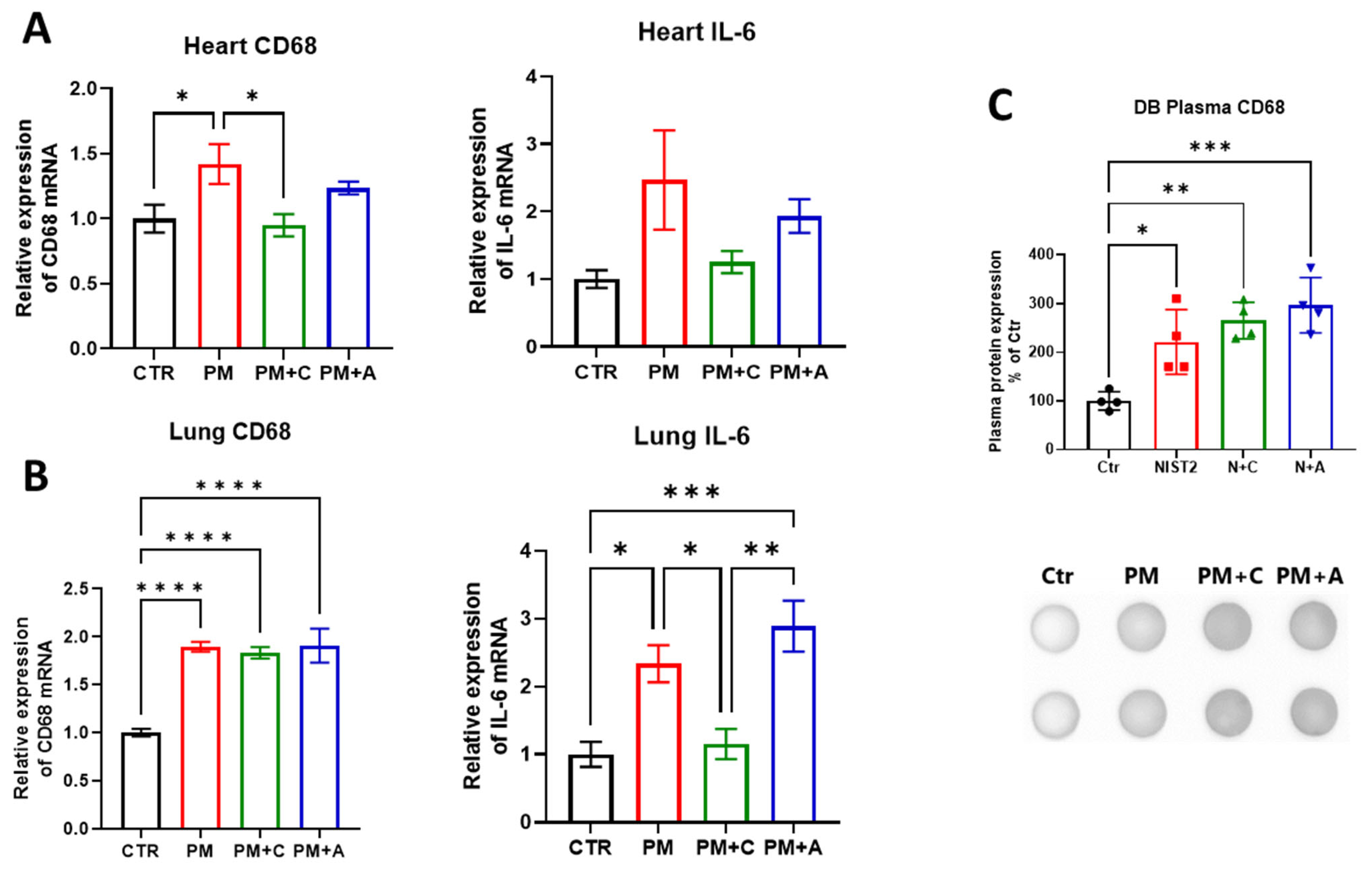

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of PM2.5 on Vascular Function

4.2. Effects of PM on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

4.3. Importance for Vulnerable Groups

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Collaborators, G.B.D.R.F. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Future Health Scenarios—Forecasting the GBD; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hahad, O.; Rajagopalan, S.; Lelieveld, J.; Sorensen, M.; Frenis, K.; Daiber, A.; Basner, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Brook, R.D.; Munzel, T. Noise and Air Pollution as Risk Factors for Hypertension: Part I—Epidemiology. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzel, T.; Sorensen, M.; Gori, T.; Schmidt, F.P.; Rao, X.; Brook, J.; Chen, L.C.; Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S. Environmental stressors and cardio-metabolic disease: Part I-epidemiologic evidence supporting a role for noise and air pollution and effects of mitigation strategies. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bont, J.; Jaganathan, S.; Dahlquist, M.; Persson, A.; Stafoggia, M.; Ljungman, P. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular diseases: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Haines, A.; Burnett, R.; Tonne, C.; Klingmuller, K.; Munzel, T.; Pozzer, A. Air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels: Observational and modelling study. BMJ 2023, 383, e077784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Klingmüller, K.; Pozzer, A.; Pöschl, U.; Fnais, M.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Cardiovascular disease burden from ambient air pollution in Europe reassessed using novel hazard ratio functions. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, K.; Vodonos, A.; Schwartz, J.; Marais, E.A.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Mickley, L.J. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smichowski, P.; Gómez, D.R. An overview of natural and anthropogenic sources of ultrafine airborne particles: Analytical determination to assess the multielemental profiles. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2024, 59, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntic, M.; Kuntic, I.; Krishnankutty, R.; Gericke, A.; Oelze, M.; Junglas, T.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Stamm, P.; Nandudu, M.; Hahad, O.; et al. Co-exposure to urban particulate matter and aircraft noise adversely impacts the cerebro-pulmonary-cardiovascular axis in mice. Redox Biol. 2023, 59, 102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadei, M.; Naddafi, K. Cardiovascular effects of airborne particulate matter: A review of rodent model studies. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, A.; Jin, X.; Natanzon, A.; Duquaine, D.; Brook, R.D.; Aguinaldo, J.G.; Fayad, Z.A.; Fuster, V.; Lippmann, M.; et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and acceleration of atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation in an animal model. JAMA 2005, 294, 3003–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Hahad, O.; Kuntic, M.; Daiber, A.; Munzel, T. Noise, Air, and Heavy Metal Pollution as Risk Factors for Endothelial Dysfunction. Eur. Cardiol. 2023, 18, e09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, T.; Zirlik, A.; Wolf, D. Pathogenic Role of Air Pollution Particulate Matter in Cardiometabolic Disease: Evidence from Mice and Humans. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2020, 33, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahad, O.; Rajagopalan, S.; Lelieveld, J.; Sorensen, M.; Kuntic, M.; Daiber, A.; Basner, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Brook, R.D.; Munzel, T. Noise and Air Pollution as Risk Factors for Hypertension: Part II—Pathophysiologic Insight. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.A.; Barajas, B.; Kleinman, M.; Wang, X.; Bennett, B.J.; Gong, K.W.; Navab, M.; Harkema, J.; Sioutas, C.; Lusis, A.J.; et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Kwong, J.C.; Kaufman, J.S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Chen, C.; van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Kim, J.; Lu, H.; Burnett, R.T.; et al. Effect modification by statin use status on the association between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and cardiovascular mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 53, dyae084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Jeong, S.; Choi, S.; Chang, J.; Choi, D.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.R.; Park, S.M. Cardiovascular Benefit of Statin Use Against Air Pollutant Exposure in Older Adults. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 32, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, R.; Hiraiwa, K.; Cheng, J.C.; Bai, N.; Vincent, R.; Francis, G.A.; Sin, D.D.; Van Eeden, S.F. Statins attenuate the development of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction induced by exposure to urban particulate matter (PM10). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 272, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostro, B.; Malig, B.; Broadwin, R.; Basu, R.; Gold, E.B.; Bromberger, J.T.; Derby, C.; Feinstein, S.; Greendale, G.A.; Jackson, E.A.; et al. Chronic PM2.5 exposure and inflammation: Determining sensitive subgroups in mid-life women. Environ. Res. 2014, 132, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeka, A.; Sullivan, J.R.; Vokonas, P.S.; Sparrow, D.; Schwartz, J. Inflammatory markers and particulate air pollution: Characterizing the pathway to disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Xing, X.; Cao, J.; Li, J.; Huang, K.; Yan, W.; et al. Impacts of Short-Term Fine Particulate Matter Exposure on Blood Pressure Were Modified by Control Status and Treatment in Hypertensive Patients. Hypertension 2021, 78, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.M.; Adar, S.D.; Szpiro, A.A.; Jorgensen, N.W.; Van Hee, V.C.; Barr, R.G.; O’Neill, M.S.; Herrington, D.M.; Polak, J.F.; Kaufman, J.D. Vascular responses to long- and short-term exposure to fine particulate matter: MESA Air (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2158–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, Y.; Pan, J. Transcriptomic analysis of key genes and pathways in human bronchial epithelial cells BEAS-2B exposed to urban particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 9598–9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Carter, J.D.; Dailey, L.A.; Huang, Y.C. Pollutant particles produce vasoconstriction and enhance MAPK signaling via angiotensin type I receptor. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Felber Dietrich, D.; Schaffner, E.; Carballo, D.; Barthelemy, J.C.; Gaspoz, J.M.; Tsai, M.Y.; Rapp, R.; Phuleria, H.C.; Schindler, C.; et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related PM(10) and decreased heart rate variability: Is the association restricted to subjects taking ACE inhibitors? Environ. Int. 2012, 48, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, P.; Daiber, A.; Oelze, M.; Brandt, M.; Closs, E.; Xu, J.; Thum, T.; Bauersachs, J.; Ertl, G.; Zou, M.H.; et al. Mechanisms underlying recoupling of eNOS by HMG-CoA reductase inhibition in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 2008, 198, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenis, K.; Kalinovic, S.; Ernst, B.P.; Kvandova, M.; Al Zuabi, A.; Kuntic, M.; Oelze, M.; Stamm, P.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Kij, A.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Aircraft Noise Exposure on Vascular Oxidative Stress, Endothelial Function and Blood Pressure: No Evidence for Adaptation or Tolerance Development. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 814921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal Krzyzanowski, M.; Apte, J.S.; Bonjour, S.P.; Brauer, M.; Cohen, A.J.; Pruss-Ustun, A.M. Air Pollution in the Mega-cities. Glob. Environ. Health Sustain. 2014, 1, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Cai, J.; Xu, B.; Bai, Y. Understanding the Rising Phase of the PM(2.5) Concentration Evolution in Large China Cities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal Care and Use Committee. Available online: https://web.jhu.edu/animalcare/procedures/mouse.html (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Tankersley, C.G.; Fitzgerald, R.S.; Levitt, R.C.; Mitzner, W.A.; Ewart, S.L.; Kleeberger, S.R. Genetic control of differential baseline breathing pattern. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 82, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Steven, S.; Tran, L.P.; Ullmann, E.; Kossmann, S.; Schmidt, F.P.; Oelze, M.; Xia, N.; Li, H.; et al. Effects of noise on vascular function, oxidative stress, and inflammation: Mechanistic insight from studies in mice. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2838–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroller-Schon, S.; Daiber, A.; Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Frenis, K.; Kalinovic, S.; Heimann, A.; Schmidt, F.P.; Pinto, A.; Kvandova, M.; et al. Crucial role for Nox2 and sleep deprivation in aircraft noise-induced vascular and cerebral oxidative stress, inflammation, and gene regulation. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3528–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntic, M.; Oelze, M.; Steven, S.; Kroller-Schon, S.; Stamm, P.; Kalinovic, S.; Frenis, K.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Kvandova, M.; et al. Short-term e-cigarette vapour exposure causes vascular oxidative stress and dysfunction: Evidence for a close connection to brain damage and a key role of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase (NOX-2). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2472–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Joseph, J.; Fales, H.M.; Sokoloski, E.A.; Levine, R.L.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Kalyanaraman, B. Detection and characterization of the product of hydroethidine and intracellular superoxide by HPLC and limitations of fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5727–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Laude, K.; McCann, L.; Doughan, A.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S. Detection of intracellular superoxide formation in endothelial cells and intact tissues using dihydroethidium and an HPLC-based assay. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C895–C902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renart, J.; Reiser, J.; Stark, G.R. Transfer of proteins from gels to diazobenzyloxymethyl-paper and detection with antisera: A method for studying antibody specificity and antigen structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 3116–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, T.; Muxel, S.; Damaske, A.; Radmacher, M.C.; Fasola, F.; Schaefer, S.; Schulz, A.; Jabs, A.; Parker, J.D.; Munzel, T. Endothelial function assessment: Flow-mediated dilation and constriction provide different and complementary information on the presence of coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundell, K.W.; Hoffman, J.R.; Caviston, R.; Bulbulian, R.; Hollenbach, A.M. Inhalation of ultrafine and fine particulate matter disrupts systemic vascular function. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Neas, L.; Herbst, M.C.; Case, M.; Williams, R.W.; Cascio, W.; Hinderliter, A.; Holguin, F.; Buse, J.B.; Dungan, K.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction: Associations with exposure to ambient fine particles in diabetic individuals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Urch, B.; Dvonch, J.T.; Bard, R.L.; Speck, M.; Keeler, G.; Morishita, M.; Marsik, F.J.; Kamal, A.S.; Kaciroti, N.; et al. Insights into the mechanisms and mediators of the effects of air pollution exposure on blood pressure and vascular function in healthy humans. Hypertension 2009, 54, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvonch, J.T.; Kannan, S.; Schulz, A.J.; Keeler, G.J.; Mentz, G.; House, J.; Benjamin, A.; Max, P.; Bard, R.L.; Brook, R.D. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter on blood pressure: Differential effects across urban communities. Hypertension 2009, 53, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftis, J.B.; Miller, M.R. Nanoparticle translocation and multi-organ toxicity: A particularly small problem. Nano Today 2019, 26, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, M.; Bard, R.L.; Wang, L.; Das, R.; Dvonch, J.T.; Spino, C.; Mukherjee, B.; Sun, Q.; Harkema, J.R.; Rajagopalan, S.; et al. The characteristics of coarse particulate matter air pollution associated with alterations in blood pressure and heart rate during controlled exposures. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.E.; Cozzi, E.; Hazarika, S.; Devlin, R.B.; Henriksen, R.A.; Lust, R.M.; Van Scott, M.R.; Wingard, C.J. Cardiac and vascular changes in mice after exposure to ultrafine particulate matter. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhao, T.; Xu, Q.; Duan, J.; Sun, Z. Evaluation of fine particulate matter on vascular endothelial function in vivo and in vitro. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 222, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntic, M.; Kuntic, I.; Cleppien, D.; Pozzer, A.; Nußbaum, D.; Oelze, M.; Junglas, T.; Strohm, L.; Ubbens, H.; Daub, S.; et al. Differential cardiovascular effects of nano- and micro-particles in mice: Implications for ultrafine and fine particle disease burden in humans. ChemRxiv 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhu, N.; Guo, Z.; Li, G.K.; Chen, C.; Sang, N.; Yao, Q.C. Particulate matter (PM10) exposure induces endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in rat brain. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 213–214, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Zhong, M.; Chen, L.C.; Sun, Q.; Rajagopalan, S. A synergistic vascular effect of airborne particulate matter and nickel in a mouse model. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 135, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Geng, J.; Wang, B.; Yuan, G.; Peng, Y.; Xu, B. PM2.5 induces endothelial dysfunction via activating NLRP3 inflammasome. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Kampfrath, T.; Thurston, G.; Farrar, B.; Lippmann, M.; Wang, A.; Sun, Q.; Chen, L.C.; Rajagopalan, S. Ambient particulates alter vascular function through induction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 111, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, H.C.; Jeong, H.M.; Lee, J.S.; Cha, H.J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.; Song, K.S. Inhibition of Urban Particulate Matter-Induced Airway Inflammation by RIPK3 through the Regulation of Tight Junction Protein Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Oelze, M.; Daub, S.; Steven, S.; Schuff, A.; Kroller-Schon, S.; Hausding, M.; Wenzel, P.; Schulz, E.; Gori, T.; et al. Vascular Redox Signaling, Redox Switches in Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase and Endothelial Dysfunction. In Systems Biology of Free Radicals and Antioxidants; Laher, I., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1177–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Mollnau, H.; Oelze, M.; August, M.; Wendt, M.; Daiber, A.; Schulz, E.; Baldus, S.; Kleschyov, A.L.; Materne, A.; Wenzel, P.; et al. Mechanisms of increased vascular superoxide production in an experimental model of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 2554–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollnau, H.; Wendt, M.; Szocs, K.; Lassegue, B.; Schulz, E.; Oelze, M.; Li, H.; Bodenschatz, M.; August, M.; Kleschyov, A.L.; et al. Effects of angiotensin II infusion on the expression and function of NAD(P)H oxidase and components of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, E58–E65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hink, U.; Li, H.; Mollnau, H.; Oelze, M.; Matheis, E.; Hartmann, M.; Skatchkov, M.; Thaiss, F.; Stahl, R.A.; Warnholtz, A.; et al. Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, E14–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, G.R.; Cai, H.; Davis, M.E.; Ramasamy, S.; Harrison, D.G. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yue, P.; Ying, Z.; Cardounel, A.J.; Brook, R.D.; Devlin, R.; Hwang, J.S.; Zweier, J.L.; Chen, L.C.; Rajagopalan, S. Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1760–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Navab, M.; Shen, M.; Hill, J.; Pakbin, P.; Sioutas, C.; Hsiai, T.K.; Li, R. Ambient ultrafine particles reduce endothelial nitric oxide production via S-glutathionylation of eNOS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 436, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Nakayama, M.; Goto, T.M.; Amano, M.; Komori, K.; Kaibuchi, K. Rho-kinase phosphorylates eNOS at threonine 495 in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 361, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oak, J.H.; Cai, H. Attenuation of angiotensin II signaling recouples eNOS and inhibits nonendothelial NOX activity in diabetic mice. Diabetes 2007, 56, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, F.; Martinka, P.; Brassanova, J.; Klimas, J.; Gvozdjakova, A.; Kucharska, J.; Bada, V.; Hulin, I.; Kyselovic, J. Passive cigarette smoking induced changes in reactivity of the aorta in rabbits: Effect of captopril. Pharmazie 2001, 56, 431–432. [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto, M.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.K. Effects of statins on vascular wall: Vasomotor function, inflammation, and plaque stability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 47, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, R.; Kan, H.; Song, W. Effects of atorvastatin on fine particle-induced inflammatory response, oxidative stress and endothelial function in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2011, 30, 1828–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M.S.; Veves, A.; Sarnat, J.A.; Zanobetti, A.; Gold, D.R.; Economides, P.A.; Horton, E.S.; Schwartz, J. Air pollution and inflammation in type 2 diabetes: A mechanism for susceptibility. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 64, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexeeff, S.E.; Coull, B.A.; Gryparis, A.; Suh, H.; Sparrow, D.; Vokonas, P.S.; Schwartz, J. Medium-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and markers of inflammation and endothelial function. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garshick, E.; Grady, S.T.; Hart, J.E.; Coull, B.A.; Schwartz, J.D.; Laden, F.; Moy, M.L.; Koutrakis, P. Indoor black carbon and biomarkers of systemic inflammation and endothelial activation in COPD patients. Environ. Res. 2018, 165, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busenkell, E.; Collins, C.M.; Moy, M.L.; Hart, J.E.; Grady, S.T.; Coull, B.A.; Schwartz, J.D.; Koutrakis, P.; Garshick, E. Modification of associations between indoor particulate matter and systemic inflammation in individuals with COPD. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Hahad, O.; Andreadou, I.; Steven, S.; Daub, S.; Munzel, T. Redox-related biomarkers in human cardiovascular disease—Classical footprints and beyond. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Kuntic, M.; Hahad, O.; Delogu, L.G.; Rohrbach, S.; Di Lisa, F.; Schulz, R.; Munzel, T. Effects of air pollution particles (ultrafine and fine particulate matter) on mitochondrial function and oxidative stress—Implications for cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 696, 108662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Zhong, J.; Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S. Effect of Particulate Matter Air Pollution on Cardiovascular Oxidative Stress Pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2018, 28, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L. Oxidative stress is the pivot for PM2.5-induced lung injury. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 184, 114362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzel, T.; Gori, T.; Al-Kindi, S.; Deanfield, J.; Lelieveld, J.; Daiber, A.; Rajagopalan, S. Effects of gaseous and solid constituents of air pollution on endothelial function. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3543–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.A.; Piao, M.J.; Fernando, P.; Herath, H.; Yi, J.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Hyun, Y.M.; Zhang, K.; Park, C.O.; Hyun, J.W. Particulate matter stimulates the NADPH oxidase system via AhR-mediated epigenetic modifications. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampfrath, T.; Maiseyeu, A.; Ying, Z.; Shah, Z.; Deiuliis, J.A.; Xu, X.; Kherada, N.; Brook, R.D.; Reddy, K.M.; Padture, N.P.; et al. Chronic fine particulate matter exposure induces systemic vascular dysfunction via NADPH oxidase and TLR4 pathways. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.J.; Miller, M.R.; Newby, D.E. Effects of Diesel Exhaust on Cardiovascular Function and Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2018, 28, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Borthwick, S.J.; Shaw, C.A.; McLean, S.G.; McClure, D.; Mills, N.L.; Duffin, R.; Donaldson, K.; Megson, I.L.; Hadoke, P.W.; et al. Direct impairment of vascular function by diesel exhaust particulate through reduced bioavailability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide induced by superoxide free radicals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Hassan, A.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Barbas, C.; Daiber, A.; Ghezzi, P.; León, R.; López, M.G.; Oliva, B.; et al. Transcription Factor NRF2 as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Diseases: A Systems Medicine Approach. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 348–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Xiong, L.; Wu, T.; Wei, T.; Liu, N.; Bai, C.; Huang, X.; Hu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. NADPH oxidases regulate endothelial inflammatory injury induced by PM(2.5) via AKT/eNOS/NO axis. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 42, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Liu, G.; Shen, L.; Qi, Y.; Hu, Q.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Du, J.; Bai, Y.; Wu, W. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by ambient fine particulate matter and potential mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, P.; Kossmann, S.; Munzel, T.; Daiber, A. Redox regulation of cardiovascular inflammation—Immunomodulatory function of mitochondrial and Nox-derived reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 109, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Perez, R.D.; Taborda, N.A.; Gomez, D.M.; Narvaez, J.F.; Porras, J.; Hernandez, J.C. Inflammatory effects of particulate matter air pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 42390–42404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, D.H.; Amyai, N.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Wang, J.L.; Riediker, M.; Mooser, V.; Paccaud, F.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Bochud, M. Effects of particulate matter on inflammatory markers in the general adult population. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2012, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden, S.F.; Tan, W.C.; Suwa, T.; Mukae, H.; Terashima, T.; Fujii, T.; Qui, D.; Vincent, R.; Hogg, J.C. Cytokines involved in the systemic inflammatory response induced by exposure to particulate matter air pollutants (PM(10)). Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; McLean, S.G.; Duffin, R.; Lawal, A.O.; Araujo, J.A.; Shaw, C.A.; Mills, N.L.; Donaldson, K.; Newby, D.E.; Hadoke, P.W. Diesel exhaust particulate increases the size and complexity of lesions in atherosclerotic mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhao, G.; Edwards, S.; Tran, J.; Rajagopalan, S.; Rao, X. Particulate air pollution exaggerates diet-induced insulin resistance through NLRP3 inflammasome in mice. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 328, 121603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liang, S.; Duan, J.; Sun, Z. Short-term PM(2.5) exposure induces sustained pulmonary fibrosis development during post-exposure period in rats. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntic, M.; Kuntic, I.; Cleppien, D.; Pozzer, A.; Nussbaum, D.; Oelze, M.; Junglas, T.; Strohm, L.; Ubbens, H.; Daub, S.; et al. Differential inflammation, oxidative stress and cardiovascular damage markers of nano- and micro-particle exposure in mice: Implications for human disease burden. Redox Biol. 2025, 83, 103644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzel, T.; Sorensen, M.; Hahad, O.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Daiber, A. The contribution of the exposome to the burden of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.N.; Balde, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Rajagopalan, S.; Balmes, J.R.; Brauer, M.; Breysse, P.N.; Brown, A.G.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Cascio, W.E.; Collman, G.W.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Impact of Particulate Air Pollution in High-Risk Populations: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2878–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Steinberg, D.M.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Yuval; Levy, I.; Chen, S.; Shafran-Nathan, R.; Levin, N.; Shimony, T.; Witberg, G.; et al. Preexisting coronary heart disease and susceptibility to long-term effects of traffic-related air pollution: A matched cohort analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 28, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., III; Turner, M.C.; Burnett, R.T.; Jerrett, M.; Gapstur, S.M.; Diver, W.R.; Krewski, D.; Brook, R.D. Relationships between fine particulate air pollution, cardiometabolic disorders, and cardiovascular mortality. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; von Klot, S.; Heier, M.; Trentinaglia, I.; Hormann, A.; Wichmann, H.E.; Lowel, H. Exposure to traffic and the onset of myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Dockery, D.W.; Muller, J.E.; Mittleman, M.A. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001, 103, 2810–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B.W.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Man, R.Y.; Leung, S.W. 17β-estradiol potentiates endothelium-dependent nitric oxide- and hyperpolarization-mediated relaxations in blood vessels of male but not female apolipoprotein-E deficient mice. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Junglas, T.; Daiber, A.; Kuntic, I.; Valar, A.; Zheng, J.; Oelze, M.; Strohm, L.; Ubbens, H.; Hahad, O.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Statins Mitigate Negative Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Effects of Particulate Matter in a Mouse Exposure Model. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010106

Junglas T, Daiber A, Kuntic I, Valar A, Zheng J, Oelze M, Strohm L, Ubbens H, Hahad O, Bayo Jimenez MT, et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Statins Mitigate Negative Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Effects of Particulate Matter in a Mouse Exposure Model. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleJunglas, Tristan, Andreas Daiber, Ivana Kuntic, Arijan Valar, Jiayin Zheng, Matthias Oelze, Lea Strohm, Henning Ubbens, Omar Hahad, Maria Teresa Bayo Jimenez, and et al. 2026. "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Statins Mitigate Negative Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Effects of Particulate Matter in a Mouse Exposure Model" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010106

APA StyleJunglas, T., Daiber, A., Kuntic, I., Valar, A., Zheng, J., Oelze, M., Strohm, L., Ubbens, H., Hahad, O., Bayo Jimenez, M. T., Münzel, T., & Kuntic, M. (2026). Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors and Statins Mitigate Negative Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Effects of Particulate Matter in a Mouse Exposure Model. Antioxidants, 15(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010106