Alterations in Adenylate Nucleotide Metabolism and Associated Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage in Rat Kidneys Under Combined Acetaminophen Toxicity and Protein Deficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Protocols

2.2. Acetaminophen Toxicity Induction

2.3. Animal Welfare Monitoring and Clinical Scoring

2.4. Histopathological Examination of Renal Tissues

2.5. Isolation of Mitochondria

2.6. Isolation of Cytosolic Fraction

2.7. Quantification of Adenine Nucleotides (AMP, ADP, ATP)

2.8. Determination of AMP Deaminase Activity

2.9. Determination of 5′-Nucleotidase Activity

2.10. Determination of Mitochondrial ATPases’ Activity

2.11. Detection of Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Toxic Doses of APAP and a Low-Protein Diet on Rat Behavior

3.2. Liver and Kidney Weight Alterations

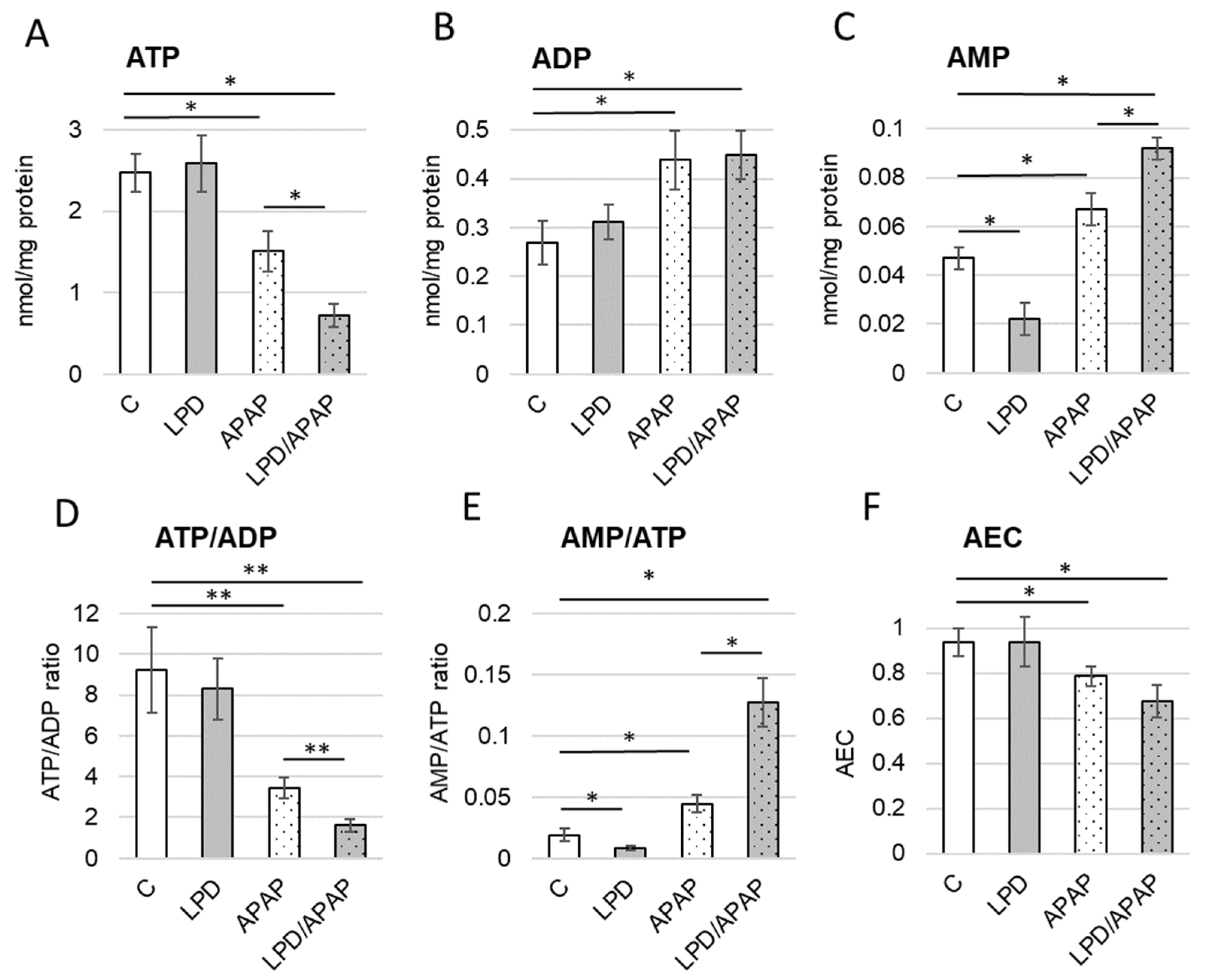

3.3. Impact of Experimental Conditions on Adenine Nucleotide Balance

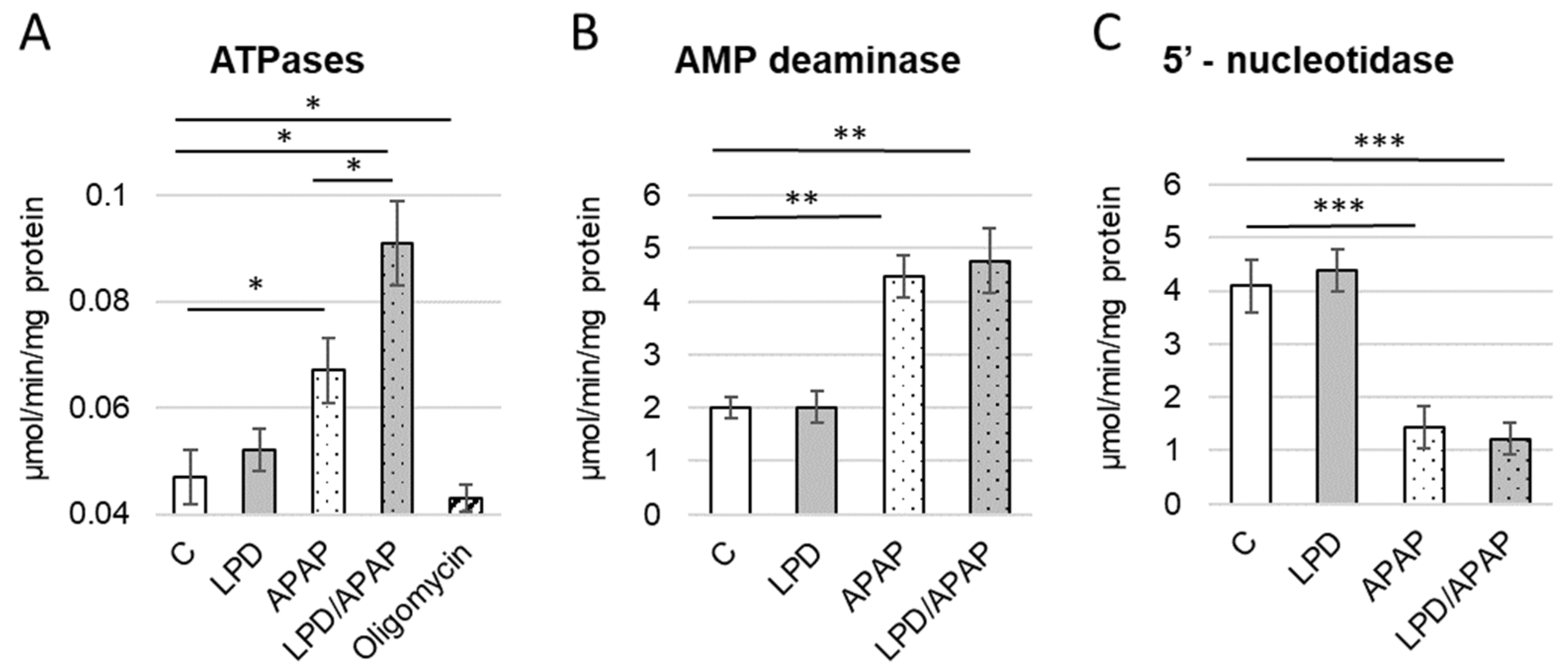

3.4. Alterations in Enzymes Involved in Energy Metabolism

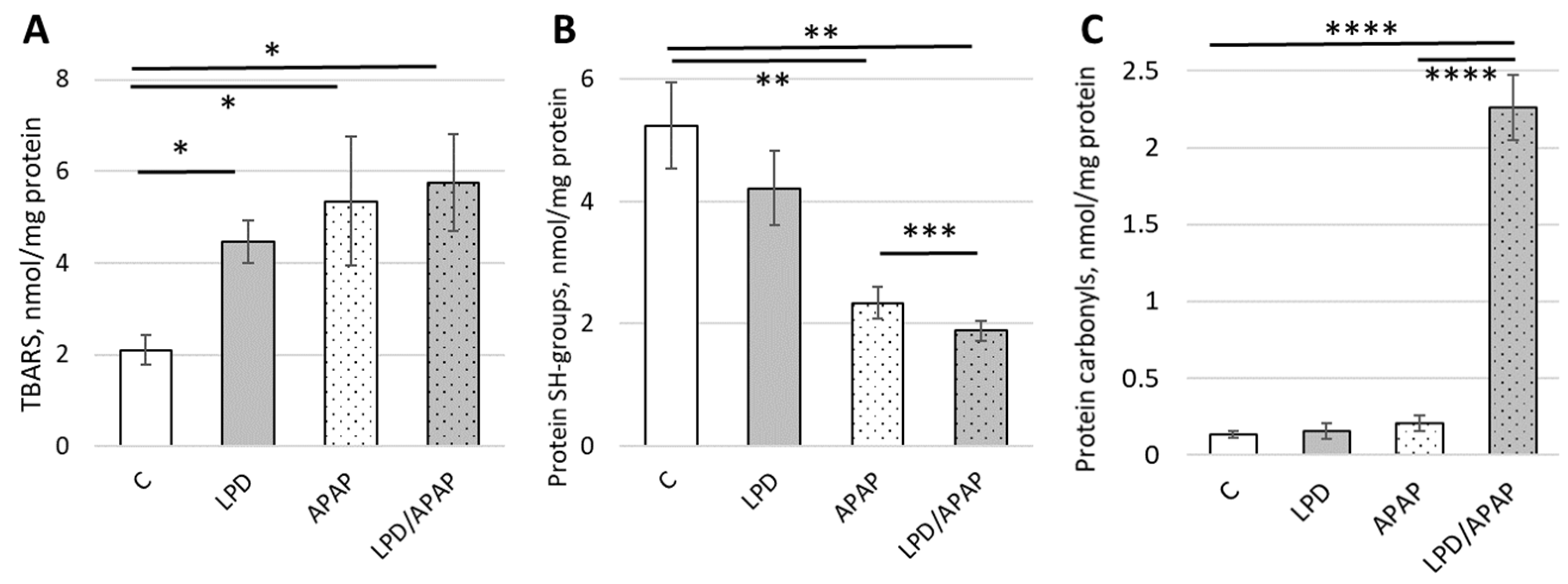

3.5. Impact of Toxic APAP Doses and Low-Protein Diet on Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Damage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Srivastava, S.P.; Kanasaki, K.; Goodwin, J.E. Loss of Mitochondrial Control Impacts Renal Health. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 543973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galichon, P.; Lannoy, M.; Li, L.; Serre, J.; Vandermeersch, S.; Legouis, D.; Valerius, M.T.; Hadchouel, J.; Bonventre, J.V. Energy depletion by cell proliferation sensitizes the kidney epithelial cells to injury. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2024, 326, F326–F337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.M.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, P.; Ko, Y.A.; Han, S.H.; Chinga, F.; Park, A.S.; Tao, J.; Sharma, K.; Pullman, J.; et al. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P. Reprogramming of Energy Metabolism in Kidney Disease. Nephron 2023, 147, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Parikh, S.M. Targeting energy pathways in kidney disease: The roles of sirtuins, AMPK, and PGC1α. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasu, M.; Kishi, S.; Nagasu, H.; Kidokoro, K.; Brooks, C.R.; Kashihara, N. The Role of Mitochondria in Diabetic Kidney Disease and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 10, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Parikh, S.M. Mitochondrial Metabolism in Acute Kidney Injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2020, 40, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, W.; Hepokoski, M.; Pham, H.; Tham, R.; Kim, Y.C.; Simonson, T.S.; Singh, P. Energy Metabolism Dysregulation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney360 2023, 4, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Q.H.; Yin, X.D.; Liu, H.X.; Zhao, B.; Huang, J.Q.; Li, Z.L. Kidney injury following ibuprofen and APAP: A real-world analysis of post-marketing surveillance data. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 750108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.K.; Solon-Biet, S.M.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; McCarthy, D.A.; McMahon, A.C.; Ruohonen, K.; Li, I.; Sullivan, M.A.; Whiddett, R.O.; Borg, D.J.; et al. Kidney disease risk factors do not explain impacts of low dietary protein on kidney function and structure. iScience 2021, 24, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, K.D.; Dougherty, B.V.; Vinnakota, K.C.; Pannala, V.R.; Wallqvist, A.; Kolling, G.L.; Papin, J.A. Predicting changes in renal metabolism after compound exposure with a genome-scale metabolic model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 412, 115390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocic, G.; Nikolic, J.; Jevtovic-Stoimenov, T.; Sokolovic, D.; Kocic, H.; Cvetkovic, T.; Pavlovic, D.; Cencic, A.; Stojanovic, D. L-arginine intake effect on adenine nucleotide metabolism in rat parenchymal and reproductive tissues. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 208239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, M.A.; Hasan, M.; Mohieldein, A. Comparative Study of 5′-Nucleotidase Test in Various Liver Diseases. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, BC01–BC03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabielska, M.A.; Borkowski, T.; Slominska, E.M.; Smolenski, R.T. Inhibition of AMP deaminase as therapeutic target in cardiovascular pathology. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 67, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D.G. Energy sensing by the AMP-activated protein kinase and its effects on muscle metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2011, 70, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybakowska, I.M.; Milczarek, R.; Slominska, E.M.; Smolenski, R.T. Effect of decaffeinated coffee on function and nucleotide metabolism in kidney. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 439, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Menon, B.; Vijayan, V.; Bansal, S. Changes in Adenosine Metabolism in Asthma. A Study on Adenosine, 5′-NT, Adenosine Deaminase and Its Isoenzyme Levels in Serum, Lymphocytes and Erythrocytes. Open J. Respir. Dis. 2015, 5, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.C.; Lee, H.T. Adenosine and protection from acute kidney injury. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012, 21, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mise, K.; Galvan, D.L.; Danesh, F.R. Shaping Up Mitochondria in Diabetic Nephropathy. Kidney360 2020, 1, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafty, M.; Abdeen, A.; Aboubakr, M. Allicin and Omega-3 fatty acids attenuates acetaminophen mediated renal toxicity and modulates oxidative stress, and cell apoptosis in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, S.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Pei, H.; Yin, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; et al. Sesamin protects against Acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity by suppressing HMOX1-mediated apoptosis and ferroptosis. Redox Rep. 2025, 30, 2529695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Viedma-Poyatos, Á.; González-Jiménez, P.; Langlois, O.; Company-Marín, I.; Spickett, C.M.; Pérez-Sala, D. Protein Lipoxidation: Basic Concepts and Emerging Roles. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorokhod, O.; Triglione, V.; Barrera, V.; Di Nardo, G.; Valente, E.; Ulliers, D.; Schwarzer, E.; Gilardi, G. Posttranslational Modification of Human Cytochrome CYP4F11 by 4-Hydroxynonenal Impairs ω-Hydroxylation in Malaria Pigment Hemozoin-Fed Monocytes: The Role in Malaria Immunosuppression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Skorokhod, O.; Valente, E.; Mandili, G.; Ulliers, D.; Schwarzer, E. Micromolar Dihydroartemisinin Concentrations Elicit Lipoperoxidation in Plasmodium falciparum-Infected Erythrocytes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spickett, C.M.; Pitt, A.R. Modification of proteins by reactive lipid oxidation products and biochemical effects of lipoxidation. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshchuk, O.M.; Kopylchuk, H.P. Activity of poliolytic pathway enzymes in rat kidneys under conditions of different protein and sucrose supply in the diet. Fiziol. Zh 2024, 70, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.G.; Nielsen, F.H.; Fahey, G.C., Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: Final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshchuk, O.M.; Kopylchuk, H.P. Characteristics of water-salt balance in protein-deficiency rats with APAP-induced toxic injury. Fiziol. Zh 2019, 65, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yang, X.; Abdelmegeed, M.A.; Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Beger, R.D.; Davis, K.; Salminen, W.F.; Song, B.J.; et al. Proteomic analysis of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and identification of heme oxygenase 1 as a potential plasma biomarker of liver injury. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2017, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshchuk, O.; Kopylchuk, H. Alimentary protein deficiency aggravates mitochondrial dysfunction in animals with APAP-induced kidney injury. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2025, 38, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.A.; Shadel, G.S. Isolation of mitochondria from cells and tissues. In Cold Spring Harbor Protocols; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, J.R.; Wegler, C.; Artursson, P. Subcellular fractionation of human liver reveals limits in global proteomic quantification from isolated fractions. Anal. Biochem. 2016, 509, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, G.; Galanti, B. Colorimetric method. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, 1st ed.; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Verlag Chemie: Weinheim, Germany, 1984; pp. 315–323. Available online: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay/alma996047823406676/01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Heinonen, J.K.; Lahti, R.J. A new and convenient colorimetric determination of inorganic orthophosphate and its application to the assay of inorganic pyrophosphatase. Anal. Biochem. 1981, 113, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.G.; Alfaqih, M.A.; Al-Shboul, O. The 4-hydroxynonenal mediated oxidative damage of blood proteins and lipids involves secondary lipid peroxidation reactions. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 2132–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguilar Diaz De Leon, J.; Borges, C.R. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress in Biological Samples Using the Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 159, 10–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parihar, M.S.; Pandit, M.K. Free radical induced increase in protein carbonyl is attenuated by low dose of adenosine in hippocampus and mid brain: Implication in neurodegenerative disorders. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2003, 22, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.; Davies, M.J.; Grune, T. Determination of protein carbonyls in plasma, cell extracts, tissue homogenates, isolated proteins: Focus on sample preparation and derivatization conditions. Redox Biol. 2015, 5, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Voloshchuk, O.M.; Kopylchuk, G.P.; Mishyna, Y.I. Activity of the mitochondrial isoenzymes of endogenous aldehydes catabolism under the conditions of acetaminophen-induced hepatitis. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2018, 90, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 82, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshchuk, O.M.; Ursatyy, M.S.; Kopylchuk, G.P. The NADH ubiquinone reductase and succinate dehydrogenase activity in the rat kidney mitochondria under the conditions of different protein and sucrose content in the diet. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2022, 94, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakpo, J.Y.; Ramachandran, A.; Orhan, H.; Curry, S.C.; Rumack, B.H.; Jaeschke, H. 4-methylpyrazole protects against APAP-induced acute kidney injury. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 409, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Jaeschke, H. A mitochondrial journey through APAP hepatotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 140, 111282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Jaeschke, H. APAP Toxicity: Novel Insights Into Mechanisms and Future Perspectives. Gene Expr. 2018, 18, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.M.; Kuhlman, C.; Terneus, M.V.; Labenski, M.T.; Lamyaithong, A.B.; Ball, J.G.; Lau, S.S.; Valentovic, M.A. S-adenosyl-l-methionine protection of acetaminophen mediated oxidative stress and identification of hepatic 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts by mass spectrometry. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 281, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Ha, J. AMPK activators: Mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, Y.W. Rifampicin activates AMPK and alleviates oxidative stress in the liver as mediated with Nrf2 signaling. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 315, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopylchuk, H.; Voloshchuk, O. Adenine nucleotide content and activity of AMP catabolism enzymes in the kidney of rats fed on diets with different protein and sucrose content. Biol. Stud. 2024, 18, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudet, L.; Mabley, J.G.; Soriano, F.G.; Pacher, P.; Marton, A.; Haskó, G.; Szabó, C. Inosine reduces systemic inflammation and improves survival in septic shock induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xiang, Q.; Mao, B.; Tang, X.; Cui, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Protective Effects of Microbiome-Derived Inosine on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Liver Damage and Inflammation in Mice via Mediating the TLR4/NF-κB Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7619–7628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesi, R.; Allegrini, S.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Piazza, L.; Moschini, R.; Jordheim, L.P.; Camici, M.; Tozzi, M.G. Cytosolic 5′-Nucleotidase II Silencing in Lung Tumor Cells Regulates Metabolism through Activation of the p53/AMPK Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.R.; Sharpe, M.R.; Williams, C.D.; Taha, M.; Curry, S.C.; Jaeschke, H. The mechanism underlying acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knight, T.R.; Fariss, M.W.; Farhood, A.; Jaeschke, H. Role of lipid peroxidation as a mechanism of liver injury after acetaminophen overdose in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2003, 76, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: A product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Heck, D.E.; Mishin, V.; Black, A.T.; Shakarjian, M.P.; Kong, A.N.; Laskin, D.L.; Laskin, J.D. Modulation of keratinocyte expression of antioxidants by 4-hydroxynonenal, a lipid peroxidation end product. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 275, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, M.N.; Jaganjac, M.; Milkovic, L.; Horvat, T.; Rojo, D.; Zarkovic, K.; Ćorić, M.; Hudolin, T.; Waeg, G.; Orehovec, B.; et al. Relationship between 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) as systemic biomarker of lipid peroxidation and metabolomic profiling of patients with prostate cancer. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelli, A.; Canosa, S.; Bergandi, L.; Skorokhod, O.A.; Biasoni, V.; Carosso, A.; Bertagna, A.; Maule, M.; Aldieri, E.; D’Eufemia, M.D.; et al. Oocyte polarized light microscopy, assay of specific follicular fluid metabolites, and gene expression in cumulus cells as different approaches to predict fertilization efficiency after ICSI. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutti, S.; Albano, E. Oxidative Stress in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Reappraisal of the Role in Supporting Inflammatory Mechanisms. Redox Exp. Med. 2022, 1, R57–R68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellati, C.; Casolari, P.; Pecorelli, A.; Sticozzi, C.; Nucera, F.; Papi, A.; Caramori, G.; Valacchi, G. Scavenger Receptor B1 Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Pathogenesis. Redox Exp. Med. 2023, 1, e230012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorokhod, O.A.; Barrera, V.; Heller, R.; Carta, F.; Turrini, F.; Arese, P.; Schwarzer, E. Malarial pigment hemozoin impairs chemotactic motility and transendothelial migration of monocytes via 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 75, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorokhod, O.; Barrera, V.; Valente, E.; Ulliers, D.; Uchida, K.; Schwarzer, E. Malarial pigment-induced lipoperoxidation, inhibited motility and decreased CCR2 and TNFR1/2 expression on human monocytes. Redox Exp. Med. 2025, 2025, e240017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negre-Salvayre, A.; Swiader, A.; Guerby, P.; Salvayre, R. Post-Translational Modifications of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Induced by Oxidative Stress in Vascular Diseases. Redox Exp. Med. 2022, 1, R139–R148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Anand, S.K.; Singh, N.; Dwivedi, U.N.; Kakkar, P. AMP-activated protein kinase: An energy sensor and survival mechanism in the reinstatement of metabolic homeostasis. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 428, 113614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, T.; Kouzu, H.; Tanno, M.; Tatekoshi, Y.; Kuno, A. Role of AMP deaminase in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 3195–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenório, M.C.d.S.; Graciliano, N.G.; Moura, F.A.; Oliveira, A.C.M.d.; Goulart, M.O.F. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): Impacts on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Dullaart, R.P.F.; Olinga, P.; Moshage, H. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Delivery of Antioxidant Enzymes: Emerging Insights and Translational Opportunities. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Hue, M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Vázquez-Carballo, C.; Palomino-Antolín, A.; García-Caballero, C.; Opazo-Rios, L.; Morgado-Pascual, J.L.; Herencia, C.; Mas, S.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Protective Role of Nrf2 in Renal Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; An, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhou, H. Activation of NRF2 Signaling Pathway Delays the Progression of Hyperuricemic Nephropathy by Reducing Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukobratovic, M.; Jevtic, J.; Zakic, T.; Korac, A.; Korac, B.; Jankovic, A. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins: Redox-metabolic homeostasis and disease pathogenesis. Redox Exp. Med. 2025, 1, e250012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, D.; Toyoshima, K.; Kojima, K.; Ishida, H.; Kaitoh, K.; Imamura, R.; Kanamitsu, K.; Kojima, H.; Funakoshi-Tago, M.; Osawa, M.; et al. Development of Keap1-Nrf2 Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitor Activating Intracellular Nrf2 Based on the Naphthalene-2-acetamide Scaffold, and its Anti-Inflammatory Effects. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coderch, C.; Bazán, H.A.; Bazan, N.G.; Surjyadipta, B.; Alvarez-Builla, J.; de Pascual-Teresa, B. Computational Insights into the Structural Basis for Reduced Hepatotoxicity of Novel Nonopioid Analgesics. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pérez-Fernández, M.; Suárez-Rojas, I.; Bai, X.; Martínez-Martel, I.; Ciaffaglione, V.; Pittalà, V.; Salerno, L.; Pol, O. Novel Heme Oxygenase-1 Inducers Palliate Inflammatory Pain and Emotional Disorders by Regulating NLRP3 Inflammasome and Activating the Antioxidant Pathway. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwata, D.; Kempen, A.L.; Dayal, N.; Brauer, N.R.; Sintim, H.O. Identification of a Selective FLT3 Inhibitor with Low Activity against VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR, c-KIT, and RET Anti-Targets. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202300442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control | LPD | APAP | LPD/APAP | H(3), p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apathy | 0 (0–0) a | 1 (0–2) b | 2 (1–2) b | 3 (2–3) c | 23.61, p = 2.32 × 10−5 |

| Fur Condition (Dullness/Loss)) | 0 (0–0) a | 2 (1–2) b | 1 (1–1) c | 2 (2–2) d | 28.40, p = 2.99 × 10−6 |

| Motor Coordination | 0 (0–0) a | 0 (0–1) b | 1 (1–2) c | 2 (2–2) d | 27.85, p = 3.91 × 10−6 |

| General Clinical Score (sum of individual scores) | 0 (0–0) a | 3 (3–4) b | 5 (3–5) c | 7 (6–7) d | 30.78, p = 9.47 × 10−7 |

| Control | LPD | APAP | LPD/APAP | H(3), p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final body weight (g) | 192 ± 7 193 (186–200) b | 155 ± 7 154 (149–170) a | 186 ± 5 185 (180–190) b | 150 ± 5 155 (148–158) a | 24.79, 1.71 × 10−5 |

| Absolute liver weight (g) | 6.77 ± 1.15 6.20 (5.90–7.92) b | 4.96 ± 0.74 4.50 (4.20–5.40) a | 8.27 ± 1.21 7.50 (7.10–9.40) c | 6.43 ± 0.59 6.20 (5.90–7.02) b | 24.67, 1.8 × 10−5 |

| Relative liver weight (mg/g body weight) | 35.63 ± 0.43 35.50 (35.30–36.00) a | 32.42 ± 0.24 32.30 (32.20–32.60) b | 43.99 ± 0.55 43.80 (43.50–44.54) c | 42.3 ± 0.37 42.10 (41.95–42.67) d | 32.84, 3.48 × 10−7 |

| Absolute kidney weight (g) | 1.53 ± 0.18 1.40 (1.38–1.70) b | 1.11 ± 0.07 1.07 (1.05–1.16) a | 1.63 ± 0.09 1.58 (1.55–1.71) c | 1.41 ± 0.11 1.35 (1.32–1.50) b | 25.62, 1.14 × 10−5 |

| Relative kidney weight (mg/g body weight) | 8.05 ± 0.12 7.99 (7.95–8.15) b | 7.25 ± 0.68 6.90 (6.70–7.90) a | 8.67 ± 0,5 8.30 (8.20–9.20) c | 9.28 ± 1.02 8.60 (8.40–10.20) c | 25.84, 1.03 × 10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Voloshchuk, O.M.; Kopylchuk, H.P.; Ursatyy, M.S.; Kovalchuk, K.A.; Skorokhod, O. Alterations in Adenylate Nucleotide Metabolism and Associated Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage in Rat Kidneys Under Combined Acetaminophen Toxicity and Protein Deficiency. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010105

Voloshchuk OM, Kopylchuk HP, Ursatyy MS, Kovalchuk KA, Skorokhod O. Alterations in Adenylate Nucleotide Metabolism and Associated Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage in Rat Kidneys Under Combined Acetaminophen Toxicity and Protein Deficiency. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoloshchuk, Oksana M., Halyna P. Kopylchuk, Maria S. Ursatyy, Karolina A. Kovalchuk, and Oleksii Skorokhod. 2026. "Alterations in Adenylate Nucleotide Metabolism and Associated Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage in Rat Kidneys Under Combined Acetaminophen Toxicity and Protein Deficiency" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010105

APA StyleVoloshchuk, O. M., Kopylchuk, H. P., Ursatyy, M. S., Kovalchuk, K. A., & Skorokhod, O. (2026). Alterations in Adenylate Nucleotide Metabolism and Associated Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidative Damage in Rat Kidneys Under Combined Acetaminophen Toxicity and Protein Deficiency. Antioxidants, 15(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010105