Nanoparticle-Based Assays for Antioxidant Capacity Determination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR)

3. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity/Activity Using Metallic Nanoparticles

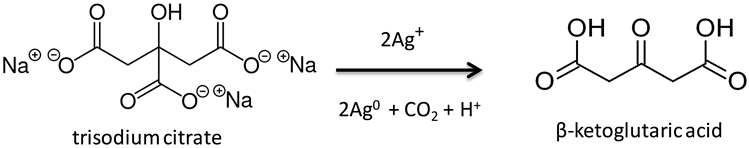

3.1. Silver NanoParticle Antioxidant Capacity (SNPAC)

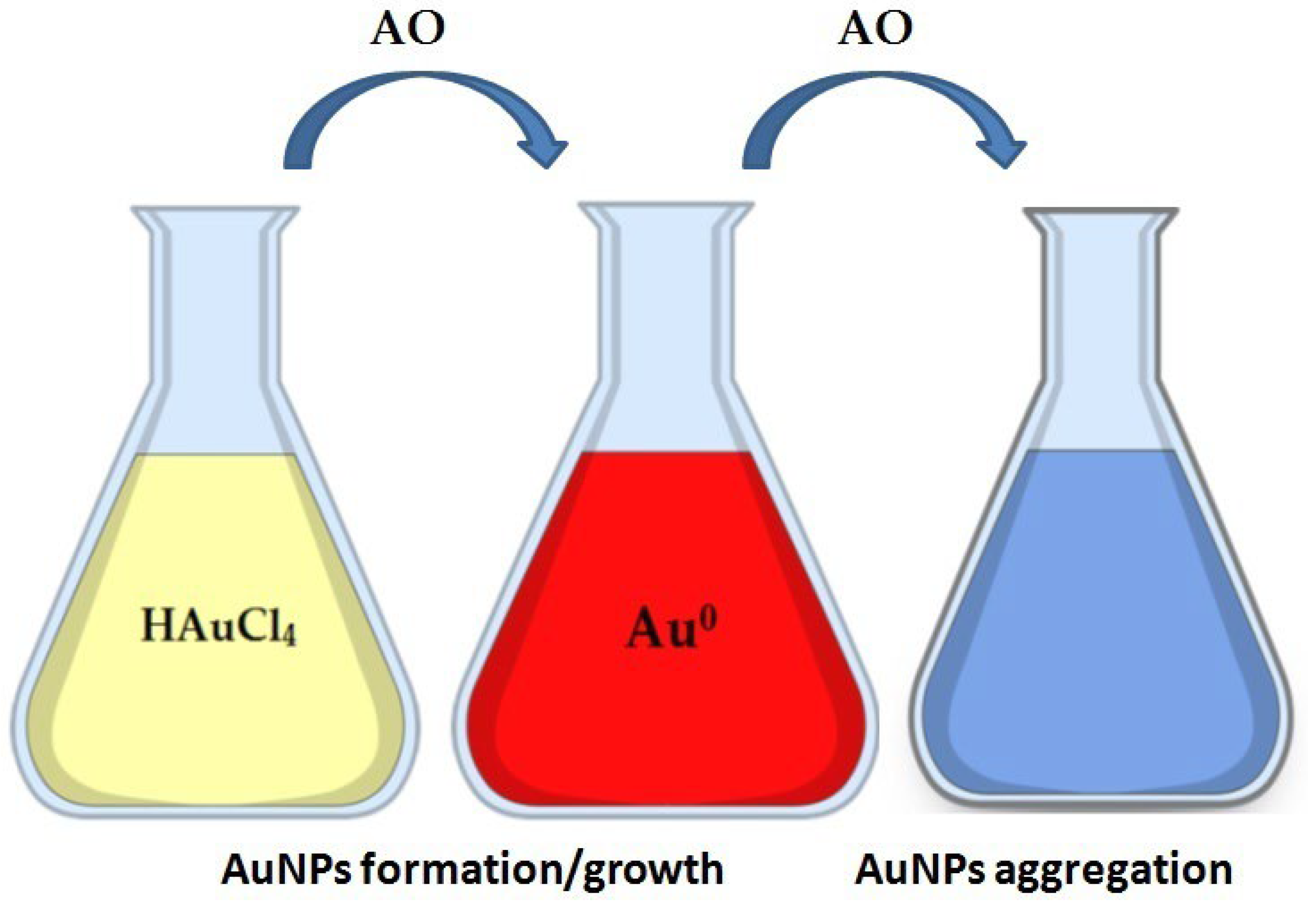

3.2. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

3.3. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles

3.3.1. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles CeONPs or Nanoceria

3.3.2. Other Metal Oxide Nanoparticles Used for AOxC Determination

3.4. Nanozymes

4. Quantum Dots (QDs)

4.1. Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs)

4.2. Semi-Conductor Metallic Nanocrystal QDs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3,4-DHBA | 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid |

| 4-HBA | 4-hydroxybenzoic acid |

| A | absorbance |

| AA | Ascorbic acid |

| AAPH | 2,2′-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay |

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| AgNPs | silver nanoparticles |

| AOs | Antioxidants |

| AOxC | antioxidant capacity |

| AuNCs | gold nanoclusters |

| AuNPs | gold nanoparticles |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CA | carminic acid |

| CDs | Carbon dots |

| CE | Capillary Electrophoresis |

| CeONPs | cerium oxide nanoparticles |

| CTAB | cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| CTAC | cetyltrimethylammonium chloride |

| Cu(I)-Nc | copper(I)-neocuproine |

| CUPRAC | Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity |

| CV | cyclic voltammetry |

| Cys | cysteine |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DPV | differential pulse voltammetry |

| DTNB | Ellman’s reagent: 5,5′-Dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

| ECL | Electrochemiluminescence |

| EM | Electromagnetic field |

| EPR | Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| ET | single electron transfer |

| FC | Folin–Ciocalteu method |

| FIA-AD | flow injection analysis with amperometric detection |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| GNSs | gold nanoshells |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| GQDs | graphene quantum dots |

| GSH | glutathione |

| GSSG | glutathione disulfide |

| HA | hyaluronic acid |

| HAT | hydrogen atom transfer |

| HPF | 2-[6-(4′-hydroxy)phenoxy-3H-xanthen-3-one-9-yl]benzoic acid |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| IC50 | Inhibitory Concentration 50% |

| IONPs | Iron Oxide Nano-particles |

| ITO | indium tin oxide |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LRET | luminescence resonance energy transfer |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| Mel | melamine |

| Met | methionine |

| MNPs | metal nanoparticles |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical antioxidant capacity |

| OXTMB | tetramethylbiphenyl |

| PBN | N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone |

| QDs | quantum dots |

| RhNPs | rhodium nanoparticles |

| RLS | the resonance light-scattering |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SEF | Surface-enhanced fluorescence |

| SEIRA | Surface-enhanced infrared absorption |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SES | Surface-enhanced spectroscopies |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| SNAPC | Silver NanoParticle Antioxidant Capacity |

| SP | surface plasmons |

| SPE | screen-printed electrode |

| SPR | surface plasmon resonance |

| ss-AuNPs | starch-stabilized gold nanoparticles |

| ssDNA | single-stranded DNA |

| SWV | square-wave voltammetry |

| TAC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| TEAC | trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TEMPOL | 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl |

| TMB | tetramethylbenzidine |

| TP | total phenolic compounds |

| TRAP | total peroxyl radical-trapping antioxidant parameter assay |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Flora, S.J.S. Role of free radicals and antioxidants in health and disease. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007, 53, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- López-Alarcón, C.; Denicola, A. Evaluating the antioxidant capacity of natural products: A review on chemical and cellular-based assays. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 763, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, J.; Flieger, W.; Baj, J.; Maciejewski, R. Antioxidants: Classification, Natural Sources, Activity/Capacity Measurements, and Usefulness for the Synthesis of Nanoparticles. Materials 2021, 14, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, L.M.; Segundo, M.A.; Reis, S.; Lima, J.L.F.C. Methodological aspects about in vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 613, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J. Detection and characterization of radicals using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin trapping and related methods. Methods 2016, 109, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozmelj, T.R.; Voinov, M.A.; Grilc, M.; Smirnov, A.I.; Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek, E.; Lucia, L.; Likozar, B. Lignin Structural Characterization and Its Antioxidant Potential: A Comparative Evaluation by EPR, UV-Vis Spectroscopy, and DPPH Assays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešić, E.; Rajić, Z.; Šakić, D. Advancements in electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy: A comprehensive tool for pharmaceutical research. Acta Pharm. 2025, 74, 551–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, T.; Dobosz, B. Road Map for the Use of Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy in the Study of Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles. Materials 2025, 18, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prima, G.; De Caro, V.; Cardamone, C.; Oliveri, G.; D’Oca, M.C. EPR Spectroscopy Coupled with Spin Trapping as an Alternative Tool to Assess and Compare the Oxidative Stability of Vegetable Oils for Cosmetics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Willner, I. Integrated nanoparticle-biomolecule hybrid systems: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 6042–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Willner, I.; Wang, J. Electroanalytical and Bioelectroanalytical Systems Based on Metal and Semiconductor Nanoparticles. Electroanalysis 2004, 16, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, N.L.; Mirkin, C.A. Nanostructures in biodiagnostics. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Angeles, G.; Alvarez-Romero, G.A.; Merkoci, A. Emerging Nanomaterials for Analytical Detection. Biosensors for Sustainable Food—New Opportunities and Technical Challenges. Compr. Anal. Chem. 2016, 74, 195–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pelle, F.; Compagnone, D. Nanomaterial-Based Sensing and Biosensing of Phenolic Compounds and Related Antioxidant Capacity in Food. Sensors 2018, 18, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedlovičová, Z.; Strapáč, I.; Baláž, M.; Salayová, A. A Brief Overview on Antioxidant Activity Determination of Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules 2020, 25, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Escarpa, A. Nanoparticles as analytical tools for in-vitro antioxidant-capacity assessment and beyond. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G. Nanostructures and Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Çapanoğlu, E.; Arda, A.Ü. Nanotechnological Methods of Antioxidant Characterization. In The Chemical Sensory Informatics of Food: Measurement, Analysis, Integration; Guthrie, B., Beauchamp, J., Buettner, A., Lavine, B.K., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 1191, pp. 209–234. ISBN 9780841230699. [Google Scholar]

- Sati, A.; Mali, S.N.; Samdani, N.; Annadurai, S.; Dongre, R.; Satpute, N.; Ranade, T.N.; Pratap, A.P. From Past to Present: Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) in Daily Life—Synthesis Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, Characterization, Toxicity, and Emerging Applications in Biomedicine, Nanoelectronics, and Materials Science. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 33999–34087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeGen, S.; Meng, G.; Aodeng, G.; Ga, L.; Ai, J. Advances in aptamer-based electrochemical biosensors for disease diagnosis: Integration of DNA and nanomaterials. Nanoscale Horiz. 2025, 10, 2668–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, M. Metal-Organic Frameworks Nanocomposite Enzymes with Peroxidase-like Activity: Can They Bring Us a New Perspective in the Field of Biological Applications? ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 4621–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavan, M.; Yousefian, Z.; Bakhtiar, Z.; Rahmandoust, M.; Mirjalili, M.H. Carbon quantum dots: Multifunctional fluorescent nanomaterials for sustainable advances in biomedicine and agriculture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 231, 121207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.I.; Kurbanoglu, S.; Ozkan, S.A. Nanomaterials-Based Nanosensors for the Simultaneous Electrochemical Determination of Biologically Important Compounds: Ascorbic Acid, Uric Acid, and Dopamine. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 49, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargazi, S.; Fatima, I.; Hassan Kiani, M.; Mohammadzadeh, V.; Arshad, R.; Bilal, M.; Rahdar, A.; Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Behzadmehr, R. Fluorescent-based nanosensors for selective detection of a wide range of biological macromolecules: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 115–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.D.; Bains, A.; Sridhar, K.; Sharma, M.; Dhull, S.B.; Goksen, G.; Chawla, P.; Inbaraj, B.S. Recent advances in the analytical methods for quantitative determination of antioxidants in food matrices. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Zhang, J.; McNicholas, T.P.; Reuel, N.F.; Kruss, S.; Strano, M.S. Recent advances in molecular recognition based on nanoengineered platforms. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Demirci Çekiç, S.; Üzer, A.; Çelik, S.E.; Bener, M.; Bekdeşer, B.; Can, Z.; Sağlam, Ş.; Önem, A.N.; Erçağ, E. Novel Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Sensors and Nanoprobes for the Characterization of Food and Biological Antioxidants. Sensors 2018, 18, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.C.; Maxwell, D.J.; Gao, X.; Bailey, R.E.; Han, M.; Nie, S. Luminescent quantum dots for multiplexed biological detection and imaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.D.; Kubota, L.T. Biosensors as a tool for the antioxidant status evaluation. Talanta 2007, 72, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.J.; Ahamed, M.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Alshamsan, A. Mechanism of ROS scavenging and antioxidant signalling by redox metallic and fullerene nanomaterials: Potential implications in ROS associated degenerative disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, J.N.; Hall, W.P.; Lyandres, O.; Shah, N.C.; Zhao, J.; Van Duyne, R.P. Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.B.; Abdala, A.; Jahan, M.I.; Susan, M.A.B.H. Nanomaterials in cosmetics: Transforming beauty through innovation and science. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2025, 44, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Bello, A.; Adams, S.M.; Onwualu, A.P.; Anye, V.C.; Bello, K.A.; Obianyo, I.I. Nano-Enhanced Polymer Composite Materials: A Review of Current Advancements and Challenges. Polymers 2025, 17, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narware, J.; Chakma, J.; Singh, S.P.; Prasad, D.R.; Meher, J.; Singh, P.; Bhargava, P.; Sawant, S.B.; Pitambara; Singh, J.P.; et al. Nanomaterial-based biosensors: A new frontier in plant pathogen detection and plant disease management. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1570318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Huang, X.; Xue, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, K. Advances in medical devices using nanomaterials and nanotechnology: Innovation and regulatory science. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 48, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çimen, D.; Ünal, S.; Denizli, A. Nanoparticle-assisted plasmonic sensors: Recent developments in clinical applications. Anal. Biochem. 2025, 698, 115753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Xie, G.; Luo, J. Mechanical properties of nanoparticles: Basics and applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamborini, F.P.; Bao, L.; Dasari, R. Nanoparticles in measurement science. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 541–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willets, K.A.; Duyne, R.P.V. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy and Sensing. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2007, 58, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreibig, U.; Vollmer, M. Optical Properties of Metal Clusters; Springer Series in Materials Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Siangproh, W.; Dungchai, W.; Rattanarat, P.; Chailapakul, O. Nanoparticle-based electrochemical detection in conventional and miniaturized systems and their bioanalytical applications: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 690, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.H.; Suh, W.H.; Stucky, G.D. Multifunctional nanosystems at the interface of physical and life sciences. Nano Today 2009, 4, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.H.D. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particle; John-Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig, U.; Genzel, L. Optical absorption of small metallic particles. Surf. Sci. 1985, 156, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcoyi, M.P.; Mpofu, K.T.; Sekhwama, M.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Developments in Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 5481–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.D.; Kubota, L.T. Review of the use of biosensors as analytical tools in the food and drink industries. Food Chem. 2002, 77, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, L.J.; Chang, S.-H.H.; Schatz, G.C.; Van Duyne, R.P.; Wiley, B.J.; Xia, Y. Localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy of single silver nanocubes. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amendola, V.; Bakr, O.M.; Stellacci, F. A study of the surface plasmon resonance of silver nanoparticles by the discrete dipole approximation method: Effect of shape, size, structure, and assembly. Plasmonics 2010, 5, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Spaeth, P.; Kar, A.; Baaske, M.D.; Khatua, S.; Orrit, M. Photothermal microscopy: Imaging the optical absorption of single nanoparticles and singlemolecules. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16414–16445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albella, P.; Alcaraz de la Osa, R.; Moreno, F.; Maier, S.A. Electric andmagnetic field enhancement with ultralow heat radia-tion dielectric nanoantennas: Considerations for surface-enhanced spectroscopies. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zheng, W.; Singh, D. Light scattering and surface plasmons on small spherical particles. Light Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.M.; Hafner, J.H. Localized surface plasmon resonance sensors. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3828–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.-S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold and silver nanoparticles in sensing and imaging: Sensitivity of plasmon response to size, shape, and metal composition. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 19220–19225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, M.; Güngör, N.; Baki, S.; Güçlü, K.; Apak, R. Development of a Silver Nanoparticle-Based Method for the Antioxidant Capacity Measurement of Polyphenols. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8052–8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.V.; Vasilescu, A.; Litescu, S.C.; Albu, C.; Danet, A.F. Metal Nano-Oxide based Colorimetric Sensor Array for the Determination of Plant Polyphenols with Antioxidant Properties. Anal. Lett. 2020, 53, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormozi Nezhad, M.R.; Karimi, M.A.; Shahheydari, F. A Sensitive Colorimetric Detection of Ascorbic Acid in Pharmaceutical Products Based on Formation of Anisotropic Silver Nanoparticles. Trans. F Nanotechnol. 2010, 17, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Eustis, S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Why gold nanoparticles are more precious than pretty gold: Noble metal surface plasmon resonance and its enhancement of the radiative and nonradiative properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomé, M.; Villaseñor, M.J.; Ríos, Á. Surface plasmon resonance optical sensors involving nanomaterials as reliable analytical tools: A critical view about performance and applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2026, 1382, 344693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, F.; Çimen, D.; Denizli, A. Plasmonic sensors for point of care diagnostics. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 265, 117042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.-C.; Gao, N.; Li, J.-F.; Wu, F.-Y. Colorimetric detection of methionine based on anti-aggregation of gold nanoparticles in the presence of melamine. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 2779–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Zeng, L.; Li, X.; Wu, A.; Zhang, Y. Colorimetric sensor for Cr (VI) by oxidative etching of gold nanotetrapods at room temperature. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 295, 122589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgönüllü, S.; Denizli, A. Plasmonic nanosensors for pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 236, 115671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Brook, M.A.; Li, Y.F. Design of Gold NanoparticleBased Colorimetric Biosensing Assays. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatselou, V.; Christodouleas, D.C.; Kouloumpis, A.; Gournis, D.; Giokas, D.L. Determination of phenolic compounds using spectral and color transitions of rhodium nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 932, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, T.; Arai, Y. Environmental geochemistry of cerium: Applications and toxicology of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1253–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir Olgun, F.A.; Üzer, A.; Ozturk, B.D.; Apak, R. A novel cerium oxide nanoparticles-based colorimetric sensor using tetramethyl benzidine reagent for antioxidant activity assay. Talanta 2018, 182, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, E.; Frasco, T.; Andreescu, D.; Andreescu, S. Portable ceria nanoparticle-based assay for rapid detection of food antioxidants (NanoCerac). Analyst 2013, 138, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, E.; Bradley, R.; Frasco, T.; Jayathilaka, D.; Marsh, A.; Andreescu, S. Metal oxide-based multisensor array and portable database for field analysis of antioxidants. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 193, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilescu, A.; Sharpe, E.; Andreescu, S. Nanoparticle-Based Technologies for the Detection of Food Antioxidants. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2012, 8, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourdikoudis, S.; Pallares, R.M.; Thanh, N.T.K. Characterization techniques for nanoparticles: Comparison and complementarity upon studying nanoparticle properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12871–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydlowska-Czerniak, A.; Tulodziecka, A. Comparison of a silver nanoparticle-based method and the modified spectrophotometric methods for assessing antioxidant capacity of rapeseed varieties. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Dong, J.; Qian, W. Growth-sensitive 3D ordered gold nanoshells precursor composite arrays as SERS nanoprobes for assessing hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity. Analyst 2011, 136, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qian, W. Phenolic acid induced growth of gold nanoshells precursor composites and their application in antioxidant capacity assay. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, E. Colorimetric Detection Based on Localised Surface Plasmon Resonance Optical Characteristics for the Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide Using Acacia Gum–Stabilised Silver Nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. Insights 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scampicchio, M.; Wang, J.; Blasco, A.J.; Sanchez Arribas, A.; Mannino, S.; Escarpa, A. Nanoparticle-based assays of antioxidant activity. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 2060–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Wei, D.; Ye, Y. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of chrysanthemum extracts and tea beverages by gold nanoparticles-based assay. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 92, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tułodziecka, A.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A. Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity of Rapeseed and Its By-Products by a Novel Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle-Based Spectrophotometric Method. Food Anal. Methods 2016, 9, 3053–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Łaszewska, A.; Tułodziecka, A. A novel iron oxide nanoparticle-based method for the determination of the antioxidant capacity of rapeseed oils at various stages of the refining process. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 4650–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, A.J.; Crevillén, A.G.; González, M.C.; Escarpa, A. Direct Electrochemical Sensing and Detection of Natural Antioxidants and Antioxidant Capacity in Vitro Systems. Electroanalysis 2007, 19, 2275–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, J.; Franus, W.; Panek, R.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Flieger, W.; Flieger, M.; Kołodziej, P. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Natural Extracts with Proven Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; Flieger, W.; Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Franus, W.; Panek, R.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Suśniak, K.; Rajtar, B.; Świątek, Ł.; Żuk, N.; et al. Antimicrobial and Apoptotic Efficacy of Plant-Mediated Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczuk, J.; Demchuk, O.M.; Borkowski, M.; Bielejewski, M. Stabilisation of Nanosilver Supramolecular Hydrogels with Trisodium Citrate. Molecules 2025, 30, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Negulescu, G.P. Methods for Total Antioxidant Activity Determination: A Review. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 1, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlala, A.R.; Moyo, M.; Van Staden, J. Natural antioxidants: Fascinating or mythical biomolecules? Molecules 2010, 15, 6905–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Tułodziecka, A.; Szłyk, E. A silver nanoparticle-based method for determination of antioxidant capacity of rapeseed and its products. Analyst 2012, 137, 3750–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects—A review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovich, M.; Prenzler, P.D.; Patsalides, E.; McDonald, S.; Robards, K. Methods for testing antioxidant activity. Analyst 2002, 127, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M.B. Some methodological problems in the determination of antioxidant activity using chromogen radicals: A practical case. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveković, D.; Milardović, S.; Roboz, M.; Grabarić, B.S. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity by flow injection analysis method with electrochemically generated ABTS radical cation. Analyst 2005, 130, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukovsky-Reyes, S.E.R.; Lowe, L.E.; Brandon, W.M.; Owens, J.E. Measurement of antioxidants in distilled spiritsby a silver nanoparticle assay. J. Inst. Brew. 2018, 124, 201–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-j.; Liu, C.-y. Seed-Mediated Growth Technique for the Preparation of a Silver Nanoshell on a Silica Sphere. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 12411–12415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everette, J.D.; Bryant, Q.M.; Green, A.M.; Abbey, Y.A.; Wangila, G.W.; Walker, R.B. Thorough study of reactivity of various compound classes toward the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8139–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Ozyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzer, A.; Durmazel, S.; Erçağ, E.; Apak, R. Determination of hydrogen peroxide and triacetone triperoxide (TATP) with a silver nanoparticles—Based turn-on colorimetric sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 247, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, P.; Donkova, B.; Karadjova, I.; Dushkin, C. Synthesis of starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles and their application as a surface plasmon resonance-based sensor of hydrogen peroxide. Colloid Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 382, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippo, E.; Serra, A.; Manno, D. Poly(vinyl alcohol) capped silver nanoparticles as localized surface plasmon resonance-based hydrogen peroxide sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 138, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Escarpa, A. Gold-nanosphere formation using food sample endogenous polyphenols for in-vitro assessment of antioxidant capacity. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 404, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, M.; Şen, F.B.; Apak, R. Heparin-stabilized gold nanoparticles-based CUPRAC colorimetric sensor for antioxidant capacity measurement. Talanta 2018, 187, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.; Serban, A.; Radulescu, C.; Danet, A.F.; Florescu, M. Bioelectrochemical evaluation of plant extracts and gold nanozyme-based sensors for total antioxidant capacity determination. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 129, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Kim, I.-K.; Tae, G.P. Fluorescent Gold Nano-probe Sensitive to Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.B. Assembly of ferrocenylhex-anethiol functionalized gold nanoparticles for ascorbic acid determination. Microchim. Acta 2010, 171, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zougagh, M.; Salghi, R.; Dhair, S.; Rios, A. Nanoparticle-based assay for the detection of virgin argan oil adulteration and its rapid quality evaluation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pelle, F.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Sergi, M.; Del Carlo, M.; Compagnone, D.; Escarpa, A. Gold Nanoparticles-based Extraction-Free Colorimetric Assay in Organic Media: An Optical Index for Determination of Total Polyphenols in Fat-Rich Samples. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 6905–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, D.; Castaneda, R.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Mendoza, S.; Escarpa, A. Fast and reliable determination of antioxidant capacity based on the formation of gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2015, 182, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, D.; González, M.C.; Escarpa, A. Sensing colorimetric approaches based on gold and silver nanoparticles aggregation: Chemical creativity behind the assay. A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 751, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enüstün, B.V.; Turkevich, J. Coagulation of Colloidal Gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3317–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, G. Detection of flavonoids and assay for their antioxidant activity based on enlargement of gold nanoparticles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 388, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, M.R.; Alimohammadi, M.; Tashkhourian, J.; Razavian, S.M. Optical detection of phenolic compounds based on the surface plasmon resonance band of Au nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 71, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, D.; González, M.C.; Escarpa, A. (Bio)-synthesis of Au NPs from soy isoflavone extracts as a novel assessment tool of their antioxidant capacity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3075–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Laskar, R.A.; Sk, I.; Kumari, D.; Ghosh, T.; Begum, N.A. A detailed study on the antioxidant activity of the stem bark of Dalbergia sissoo Roxb., an Indian medicinal plant. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Rao, Y.; Ma, X.; Dong, J.; Qian, W. Raman spectroscopy for scavenging activity assay using nanoshell precursor nanocomposites as SERSprobes. Anal. Methods 2011, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudeep, P.K.; Joseph, S.T.; Thomas, K.G. Selective detection of cysteine and glutathione using gold nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6516–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Kundu, S.; Panigrahi, S.; Praharaj, S.; Pande, S.; Jana, S.; Pal, T. Biomolecule induced nanoparticle aggregation: Effect of particle size on interparticle coupling. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 313, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, C. Visual detection of ascorbic acid via alkyne-azide click reaction using gold nanoparticles as a colorimetric probe. Analyst 2010, 135, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.P.; Duan, X.R.; Liu, C.H.; Du, B.A. Selective determination of cysteine by resonance light scattering technique based on self-assembly of gold nanoparticles. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 351, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, H.; Dong, J.; Qian, W. Determination of hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity of phenolic acids by employing gold nanoshells precursor composites as nanoprobes. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.E.; Bekdeşer, B.; Apak, R. A novel colorimetric sensor for measuring hydroperoxide content and peroxyl radical scavenging activity using starch-stabilized gold nanoparticles. Talanta 2019, 196, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, X.Y.; Dong, J.; Qian, W.P. Development of Methodology Based on the Formation Process of Gold Nanoshells for Detecting Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging Activity. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 8916–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, M.; Ding, C.; Zhu, A.; Tian, Y. Ratiometric fluorescence probe for monitoring hydroxyl radical in live cells based on gold nanoclusters. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Wu, N.; Sun, B.; Su, H.C.; Ai, S.Y. Colorimetric detection of peroxynitrite-induced DNA damage using gold nanoparticles, and on the scavenging effects of antioxidants. Microchim. Acta 2013, 180, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Noble metals on the nanoscale: Optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Sánchez-Mendieta, V.; Camacho-López, M.A.; Gómez-Espinosa, R.M.; Camacho-López, M.A.; Arenas-Alatorre, J.A. Solventless synthesis and optical properties of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Camellia sinensis extract. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 3103–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Navarro, A.; Fernández-Romero, J.M.; Gómez-Hens, A. Determination of antioxidant additives in foodstuffs by direct measurement of gold nanoparticle formation using resonance light scattering detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 695, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, J. Phenolic acids induced growth of 3D ordered gold nanoshell composite array as sensitive SERS nanosensor for antioxidant capacity assay. Talanta 2018, 190, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.C.; Liu, J.; Hu, M.; Song, L.; Li, M.; Kou, Q.; Huang, R.; Sun, L.; Wen, C. An Au@CuS@CuO2 nanoplatform with peroxidase mimetic activity and self-supply H2O2 properties for SERS detection of GSH. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 340, 126376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choleva, T.G.; Kappi, F.A.; Giokas, D.L.; Vlessidis, A.G. Paper-based assay of antioxidant activity using analyte-mediated on-paper nucleation of gold nanoparticles as colorimetric probes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 860, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danet, A.F. Recent Advances in Antioxidant Capacity Assays. In Antioxidants-Benefits, Sources, Mechanisms of Action; Waisundara, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Yu, Z.; Li, G.X. Enlargement of gold nanoparticles on the surface of a self-assembled monolayer modified electrode: A mode in biosensor design. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 5227–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Ai, S.; Shang, K.; Meng, X.; Wang, C. Electrochemical determination of NADH using a glassy carbon electrode modified with Fe3O4 nanoparticles and poly-2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid, and its application to the determination of antioxidant capacity. Microchim. Acta 2011, 174, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Calas-Blanchard, C.; Cortina-Puig, M.; Baohong, L.; Marty, J.-L. An electrochemical method for sensitive determination of antioxidant capacity. Electroanalysis 2009, 21, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, A.G.; Barison, A.; Oliveira, V.S.; Foti, L.; Krieger, M.A.; Dhalia, R.; Viana, I.F.T.; Schreiner, W.H. The mechanism of cysteine detection in biological media by means of vanadium oxide nanoparticles. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2012, 14, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lagger, G.; Tacchini, P.; Girault, H.H. Generation of OH radicals at palladium oxide nanoparticle modified electrodes, and scavenging by fluorescent probes and antioxidants. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2008, 619–620, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, B.N.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative cleavage-based upconversional nanosensor for visual evaluation of antioxidant activity of drugs. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 64, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Nanozymes: Classification, Catalytic Mechanisms, Activity Regulation, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4357–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J. Boosting the oxidase mimicking activity of nanoceria by fluoride capping: Rivaling protein enzymes and ultrasensitive F− detection. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 13562–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Ju, E.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Self-Assembly of Multi-nanozymes to Mimic an Intracellular Antioxidant Defense System. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 6646–6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Yin, J.J.; Hou, S.; Wen, T.; He, W.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Formation of PdPt alloy nanodots on gold nanorods: Tuning oxidase-like activities via composition. Langmuir 2011, 27, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C. A facile method for the sensing of antioxidants based on the redox transformation of polyaniline. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 208, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshath, U.S.; Shubha, L.R.; Bhatt, P.; Thakur, M.S. Quantum dots as optical labels for ultrasensitive detection of polyphenols. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 57, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Xiao, L.; Ren, C.; Chen, X. Carbon Dots as Fluorescent/Colorimetric Probes for Real-Time Detection of Hypochlorite and Ascorbic Acid in Cells and Body Fluid. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 15477–15483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Qureshi, A.; Azhar, M.; Hassan, Z.U.; Gul, S.; Ahmad, S. Recent Progress of Fluorescent Carbon Dots and Graphene Quantum Dots for Biosensors: Synthesis of Solution Methods and their Medical Applications. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 2623–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Welsher, K.; Robinson, J.T.; Goodwin, A.; Zaric, S.; Dai, H. Nano-Graphene Oxide for Cellular Imaging and Drug Delivery. Nano Res. 2008, 1, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.H.; Abdouss, M.; Rahdar, A.; Pandey, S. Graphene Quantum Dots: Background, Synthesis Methods, and Applications as Nanocarrier in Drug Delivery and Cancer Treatment: An Updated Review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 161, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Martínez, S.; Valcárcel, M. Graphene quantum dots as sensor for phenols in olive oil. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 197, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maghrabey, M.; Yamamichi, A.; Abdel-Hakim, A.; Kishikawa, N.; Kuroda, N. Application of Ferric–Graphene Quantum Dot Complex for Evaluation and Imaging of Antioxidants in Foods Based on Fluorescence Turn-Off–On Strategy. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cui, Y.; Song, L.; Liu, X.; Hu, Z. Microwave Assisted One-Pot Synthesis of Graphene Quantum Dots as Highly Sensitive Fluorescent Probes for Detection of Iron Ions and PH Value. Talanta 2016, 150, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Yan, X.; Qiu, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, X.E. Turn-on fluorescent assay for antioxidants based on their inhibiting polymerization of dopamine on graphene quantum dots. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 225, 117516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Su, X. A simple and convenient fluorescent strategy for the highly sensitive detection of dopamine and ascorbic acid based on graphene quantum dots. Talanta 2018, 189, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, R.S.; Zhou, J.; Huang, C.Z. Branched polyethylenimine-functionalized carbon dots as sensitive and selective fluorescent probes for N-acetylcysteine via an off-on mechanism. Analyst 2017, 142, 4221–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, Y.; Ruiyi, L.; Yongqiang, Y.; Zaijun, L.; Zhiguo, G.; Guangli, W.; Junkang, L. Pentaethylene hexamine and penicillamine co-functionalized graphene quantum dots for fluorescent detection of mercury(II) and glutathione and bioimaging. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 203, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y.N.; Serge, K. A rapid and label-free dual detection of Hg (II) and cysteine with the use of fluorescence switching of graphene quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 207, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yang, R.; Qu, C.J.; Mao, H.C.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.J.; Qu, L.B. Synthesis of glycinefunctionalized graphene quantum dots as highly sensitive and selective fluorescent sensor of ascorbic acid in human serum. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Na, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Su, X. Graphene quantum dots as selective fluorescence sensor for the detection of ascorbic acid and acid phosphatase via Cr(vi)/Cr(iii)-modulated redox reaction. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3278–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, X.L.; Li, M.; Gao, H.; Sun, J.; Zhu, S.Y.; Han, S.; Jia, L.N.; Zhao, X.E.; Wang, H. A “turn-on” fluorescence sensor for ascorbic acid based on graphene quantum dots via fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaloo, A.; Nguyen, S.; Lee, B.H.; Valimukhametova, A.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R.; Sottile, O.; Dorsky, A.; Naumov, A.V. Doped Graphene Quantum Dots as Biocompatible Radical Scavenging Agents. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Ju, H. Electrochemiluminescence sensors for scavengers of hydroxyl radical based on its annihilation in CdSe quantum dots film/peroxide system. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 6690–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Tang, L.; Chang, H.; Li, J. Graphene oxide amplified electrogenerated chemiluminescence of quantum dots and its selective sensing for glutathione from thiol-containing compounds. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9710–9715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Yan, X.P. Chemical redox modulation of the surface chemistry of CdTe quantum dots for probing ascorbic acid in biological fluids. Small 2009, 5, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharya, S.C.; Saha, A. Probing of ascorbic acid by CdS/dendrimer nanocomposites: A spectroscopic investigation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmateenejad, B.; Shamsipur, M.; Khosousi, T.; Shanehsaz, M.; Firuzi, O. Antioxidant activity assay based on the inhibition of oxidation and photobleaching of L-cysteine-capped CdTe quantum dot. Analyst 2012, 137, 4029–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshkumar, A.; Sivasudha, T.; Jeyadevi, R.; Sangeetha, B.; Ananth, D.A.; Aseervatham, G.S.B.; Nagarajan, N.; Renganathan, R.; Kathiravan, A. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Merremia emarginata using thio glycolic acid-capped cadmium telluride quantum dots. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 101, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.Z.; Ju, H.X. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence from a CdSe Nanocrystal film and its sensing application in aqueous solution. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 6871–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. Interaction of flavonoids (baicalein and hesperetin) with CdTe QDs by optical and electrochemical methods and their analytical applications. Colloids Surf. B Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 421, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loima, T.; Yoon, J.-Y.; Kaarj, K. Microfluidic Sensors Integrated with Smartphones for Applications in Forensics, Agriculture, and Environmental Monitoring. Micromachines 2025, 16, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Assay Mechanism (Observed Change) | Detection (λmax) | Examples | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs | Formation/Growth (Reduction); Color Change: colorless salt solution to dark red/red colloidal solution. | 555 nm; 540 nm; 530 nm (General LSPR for spherical AuNPs). | AOxC of phenolic acids, chrysanthemum extracts and tea beverages. Detection of Daizeol, Puerarin, and Quercetin | [77,78] |

| AuNPs | Aggregation Color Change: red (dispersed) to blue (aggregated). | ~520 nm (for monitoring dispersed state). | Detection of polynucleotides based on distance-dependent optical properties; detection of proteins. | [65] |

| AgNPs | Seed Growth (SNPAC); Color Change: No color into pale yellow (seeds formation); gradual change from pale yellow to more intense in the reaction mixture (measurements) | 423 nm; 405 nm (used in some comparisons). | TAC of polyphenols, vitamins C and E; Rapeseed varieties; Fruit juices and herbal teas | [73] |

| CeONPs (NanoCerac, CERAC) | Formation CeONPs Color Change: Formation of red-purple solutions of CeO NPs. | 510 nm | TAC determination of rapeseed, white flakes, and meal | [79] |

| IONPs | Formation/Growth Color Change: Formation of yellow-orange solutions. | 396 nm | TAC determination of rapeseed oils at various stages of the refining process. | [80] |

| Detection Mechanism | Detection Type | Detection Conditions | Analyzed Antioxidant | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs Formation/Growth | Spectrophotometry (LSPR) | The absorption peaks at 555 nm | Phenolic acids (e.g., ferulic, vanillic and syringic acids) in virgin argan oil | [106] |

| AuNPs Formation | UV–Vis–NIR Fluorescence | The absorption peaks at ~550 nm. Fluorescence at ~448 nm (2.7 eV emission energy) | Polyphenols (59.8 mg CAE/g), terpenoids (β-cariophyllene, linalool, cis-jasmone, α-terpineol, δ-cadinene, indole, geraniol) in green tea (Camellia sinensis) | [126] |

| the growth of GNS precursor composites (SiO2/GNPs) on ITO electrode surface | the UV-vis-NIR (the intensified LSPR features); CV (reduced cathodic currents) | (SiO2/GNPs nanocomposites)/APTES/ITO (0.01 M PBS pH 7.4, 3.3 × 10−4 M AuCl4−, 1.6 × 10−3 M K2CO3, AOs, stirring for 30 min) | Phenolic compounds: Ferulic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid and gallic acid | [75] |

| AuNPs formation | UV–vis 500–700 nm | 5 mL of the sample solution, 150 µL of 0.1 M aq. HAuCl4 stirring and heating at 45 °C for 10 min. | The total polyphenol content of AED (153.35 ± 4.42 mg GAE g−1) and MED (189.79 ± 4.27 mg GAE g−1). The flavonoid content of AED (45.33 ± 0.14 mg QE g−1) and MED (49.41 ± 0.49 mg QE g−1) in the aqueous (AED) and methanol (MED) Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. extracts | [114] |

| AuNP enlargement, and a Au electrode modified with Au seeds | UV-vis and CV | The Au-NP growth solution: 2.06 × 102 μM HAuCl4, 2.0 × 103 μM CTAC in 1 × 104 μM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 heated for 20 min at 45 °C | Flavonoids (quercetin, daizeol and puerarin) in radix astragali, (80% flavonoids); and soybean (40% flavonoids) extracts | [111] |

| AuNPs growth | Spectrophotometry (LSPR). Detection at 545 nm. | 100 µL of 5 × 10−4 M AuCl4−, 600 µL of 3.7 × 10−3 M CTAB, 300 µL of 2 × 10−4 M sodium citrate, 1 mL of extract; 10 min at 45 °C | Flavonoids, triterpenes, vitamin, and polysaccharides in (C. morifolium) extracts and tea beverages | [78] |

| GNSs as the optical nanoprobes | Spectrophotometry (the red shift from 530 nm to 780 nm) | The reduction of AuCl4− with NaBH4 to GNSs used to fabrication of SiO2/GNPs. AOs inhibit the H2O2-induced growth of GNSs | Phenolic acids: trans-cinnamic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, protocatechuic acid and caffeic acid in licorice, mulberry leaves, chrysanthemum, green tea, black tea, honeysuckle, baicalin, ephedra and rooibos. | [120] |

| AuNPs growth | Spectrophotometry (LSPR) Detection at 568 nm. | Addition of 0.1 M CTAC, 0.001 M HAuCl4 | Hydroquinone, catechol, and pyrogallol in pharmaceutical preparations and water | [112] |

| AuNPs growth | stopped-flow mixing technique and RLS as detection system | the presence of CTAB used as stabilizing agent | Gallic acid, propyl gallate, octyl gallate, dodecyl gallate, butylated hydroxyanisol, butylated hydroxytoluene, ascorbic acid, sodium citrate in foodstuffs | [127] |

| AuNPs growth | Spectrophotometry (LSPR) detection at 555 nm and CV | 1 × 10−3 M AuCl4−, 3.7 × 10−3 M, CTAC, and 2 × 10−4 M sodium citrate in 1 × 10−2 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0); 10 min heating at 45 °C | Phenolic acids: propyl gallate, caffeic acid, protocatechuic acid, ferulic acid, and vanillic acid in plant extracts and food samples | [77] |

| AuNPs aggregation of probes | Color change from a red-to-purple (or pink) color change) or UV-vis spectrometer | the terminal azide- and alkyne-functionalized AuNPs in the presence of Cu2+ | AA (3 nM LOD) in citrus fruits, presence of other reducing compounds: glucose, cysteine, dopamine, thiamine and uric acid | [118] |

| AuNPs precursor composite (SiO2)/AuNP) | SERS | AOs inhibit Au3+ reduction in the presence of H2O2 and deposition of Au0 onto the surface of the SiO2/AuNPs. | tannic acid, citric acid, ferulic acid, and tartaric acid | [74] |

| Au nanozyme-sensor | CV, DPV, EI | AuNPs nanozymes act as natural peroxidases (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) | lavender and sea buckthorn extracts; Trolox as standard AO | [103] |

| growth of AuNPs precursor composite (SiO2)/AuNP) | UV–vis spectrophotometry, SERS | SiO2/AuNPs, K2CO3/HAuCl4 solution, AOs were stirred for 30 min at RT | phenolic acids: vanillic acid (10–250 µM), syringic acid (10–110 µM), and gallic acid (5–55 µM) | [128] |

| Au@CuS core–shell loaded with CuO2 NPs | SERS (decrease in the Raman signal of OXTMB) | a slightly acidic environment, Cu2+, H2O2, TMB, GSH | GSH; LOD 1.2 × 10−13 mol∙L−1 in serum samples | [129] |

| AuNPs growth | image acquisition using a desktop flatbed scanner; visual or optical color changes on paper based sensor | paper nucleation of AuNPs as colorimetric probes | GAE in teas and wines Linear range: 10 μM–1.0 mM, LOD < 1.0 μM, 3.6–12.6% RSD | [130] |

| AuNPs Growth | The absorbance at 537, 539, 571, 573 nm. | 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 15.2 µM CTAC, 1 mM HAuCl4, AOs; stirred (2 min), heated at 45 °C (10 min), frozen 25 min | aglycones-genistein, daidzein, and glycosides: genistin and daidzin in soy extracts | [113] |

| Process | Reaction | Rate Constant | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Generation (Electrochemistry) | PdO + H2O + 2e→Pd + 2OH−● | k0 | Electrochemical reduction of PdO to metallic Pd, exposing active sites |

| OH Radical Generation (Catalytic) | H2O2→2OH−● | k1 | Catalytic dissociation rate constant of H2O2 on the freshly exposed metallic Pd |

| H2O2 Generation (In Situ) | O2 + H2O + 2e→H2O2 + 2OH−● | kr | Electrochemical reduction of dissolved O2 to H2O2 |

| Catalytic Cycle (Current Enhancement) | Pd + 2OH−●→PdO + H2O | k2 | Re-oxidation: OH−● reoxidize metallic Pd to PdO causing the enhancement of the cathodic reduction current |

| Competitive Consumption (AO Measurement) | OH−● + AO→H2O + AO+ (AO+ oxidized form of AO) | kAO | Scavenging: AO competes with Pd for the OH−●. Higher kAO results in a lower catalytic current |

| Additional Reactions | H2O2 + 2e→2OH−● | k3 | Electrochemical reduction rate constant of H2O2 |

| Mechanism | QDs | Target/Type of Antioxidant (LODs) | Measurement Conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECL Quenching | CdSe QDs | GSH (1.0 μM), L-Cys (2.0 μM) | OH● are produced from H2O2 reduction by electron-injected QDs; AOs scavenge free radicals, causing ECL quenching. | [160] |

| ECL Quenching—Scavenging of CdTe-QDs●+ amplified by Graphene Oxide (GO) | CdTe QDs (amplified by GO) | GSH (8.3 μM) | Selective detection of GSH due to stronger hydrogen bonding with GO than GSSG or Cys. GO enhances the ECL signal and generation of QD radicals CdTe-QDs●+ GSH causes total quenching of ECL. | [161] |

| Fluorescence Restoration | GSH-CdTe QDs (capped by GSH) | AA (74 nM) in urine, plasma | QDs are initially quenched by KMnO4 (oxidation of Te atoms). AA reduces the oxidized forms (CdTeO3/TeO2), restoring the fluorescence (turn-on effect). | [162] |

| Photoluminescence Quenching | CdS/dendrimers | AA (3.3 μM) in tablets | AA quenches the photoluminescence, which is linearly correlated with AA concentration. | [163] |

| Inhibition of Photobleaching | CdTe-QDs (L-Cys) | Flavonoids (quercetin, tannic acid, caffeic acid, gallic acid, naringin, trolox); in teas | the QD solution (30 nM) generate ROS under UV irradiation (254 nm) for 30 s, causing photobleaching. AOs scavenge ROS, inhibiting bleaching and preserving fluorescence. AOxC is measured as percentage inhibition of photobleaching. | [164] |

| Fluorescence Quenching | TGA-capped CdTe-QDs | Extract Merremia emarginata (Polyphenols) in herbs | AOs trap the holes (positive charge carriers) created during excitation, preventing electron-hole recombination and thus quenching the fluorescent emission. The reduction in the signal depends on the amount of extract added. | [165] |

| Fluorescence Quenching | CdTe QDs | Baicalein (24.5 ngmL−1; 1.3%RSD), Hesperitin (9.7 ng mL−1; 1.97%RSD) in urine | Quenching due to optical and electrochemical interaction. Conditions: Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, 0.24 mM QDs, 10 min of incubation | [167] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flieger, J.; Żuk, N.; Grabias-Blicharz, E.; Puźniak, P.; Flieger, W. Nanoparticle-Based Assays for Antioxidant Capacity Determination. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121506

Flieger J, Żuk N, Grabias-Blicharz E, Puźniak P, Flieger W. Nanoparticle-Based Assays for Antioxidant Capacity Determination. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121506

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlieger, Jolanta, Natalia Żuk, Ewelina Grabias-Blicharz, Piotr Puźniak, and Wojciech Flieger. 2025. "Nanoparticle-Based Assays for Antioxidant Capacity Determination" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121506

APA StyleFlieger, J., Żuk, N., Grabias-Blicharz, E., Puźniak, P., & Flieger, W. (2025). Nanoparticle-Based Assays for Antioxidant Capacity Determination. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121506