An Antioxidative Exopolysaccharide–Protein Complex of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus and Its Epithelial Barrier-Protective Effects in Caco-2 Cell Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cs-HK1 Fermentation and EPS-LM Isolation

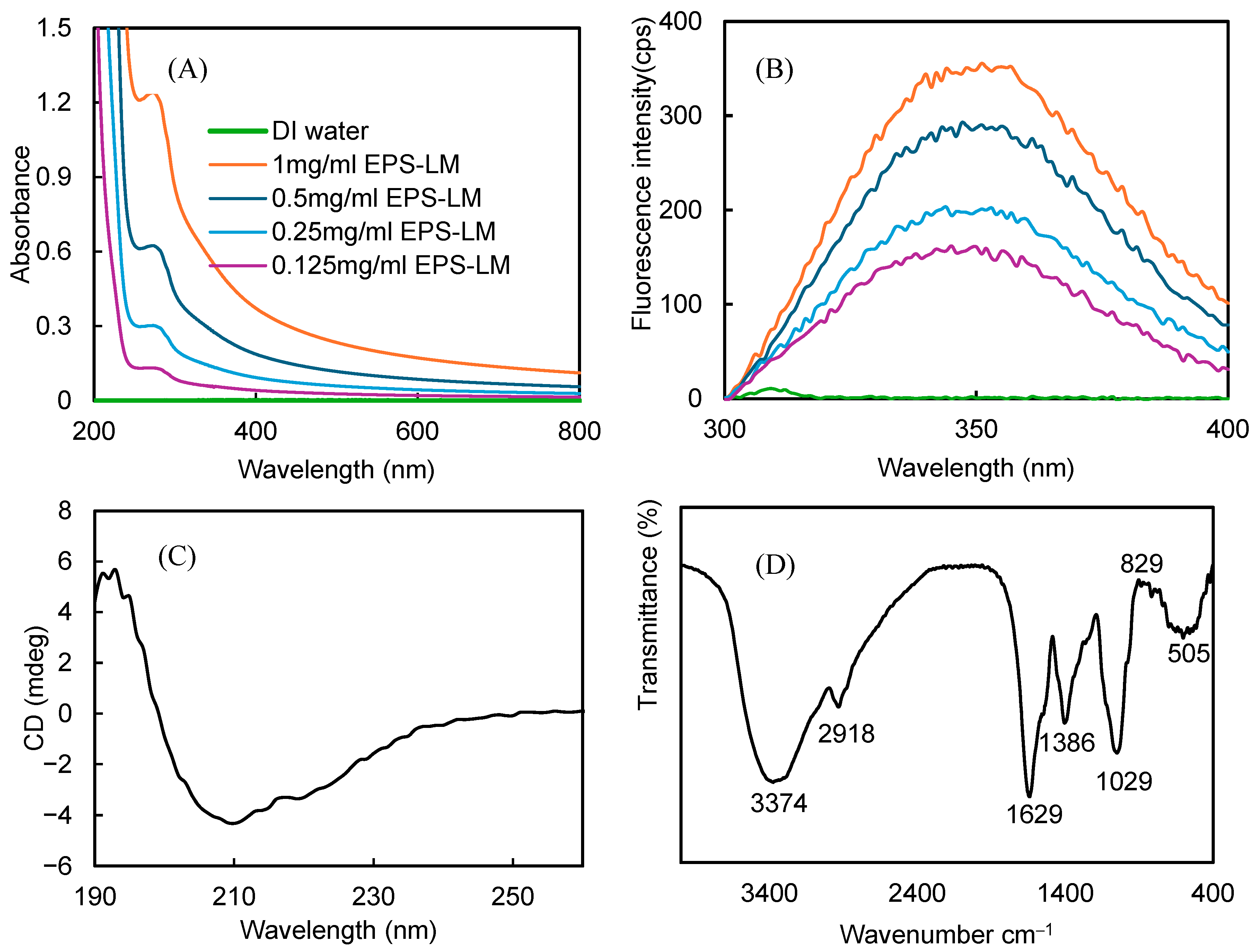

2.2. Characterization and Analysis of EPS-LM

2.2.1. Chemical Composition Analysis

2.2.2. Determination of Molecular Weight

2.2.3. FT-IR Analysis

2.2.4. Amino Acid Analysis

2.2.5. UV–Vis and Fluorescence Spectral Analysis

2.2.6. Circular Dichroism Analysis

2.2.7. Endotoxin Detection

2.3. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.3.1. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Assay

2.3.2. ABTS Radical-Scavenging Assay

2.4. Assessment of EPS-LM Bioactivities

2.4.1. Caco-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cell Culture

2.4.2. Reagents

2.4.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4.4. Cell Viability Staining Assay

2.4.5. Intracellular ROS Assay

2.4.6. Measurement of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.4.7. TEER Measurement

2.4.8. Cell Permeability Assay

2.4.9. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.4.10. Western Blotting Analysis

2.4.11. Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition and Molecular Weight of EPS-LM

3.2. Structural Characteristics

3.3. Monosaccharide and Amino Acid Composition

3.4. Antioxidant Activities

3.5. Effects of EPS-LM on Caco-2 Cell Viability

3.6. Effects of EPS-LM on Antioxidant Responses in Caco-2 Cells

3.6.1. EPS-LM Reduces ROS Levels and Restores Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.6.2. EPS-LM Modulates NRF2-NQO1 Signaling Under Oxidative Stress

3.7. Protective Effects of EPS-LM on Epithelial Barrier Function in Caco-2 Cell Culture

3.7.1. EPS-LM Alleviates H2O2-Induced Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction

3.7.2. EPS-LM Restores Tight-Junction Components Under Oxidative Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J.M. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ding, L.; Lu, Q.; Chen, Y.H. Claudins in intestines: Distribution and functional significance in health and diseases. Tissue Barriers 2013, 1, e24978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Lasch, K.; Zhou, W. Irritable bowel syndrome: Methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. The confluence of increased permeability, inflammation, and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G775–G785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, K.A.; Raffals, L.E.; Camilleri, M. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Underpinning Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 4306–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patlevic, P.; Vaskova, J.; Svorc, P., Jr.; Vasko, L.; Svorc, P. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in human gastrointestinal diseases. Integr. Med. Res. 2016, 5, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petecchia, L.; Sabatini, F.; Usai, C.; Caci, E.; Varesio, L.; Rossi, G.A. Cytokines induce tight junction disassembly in airway cells via an EGFR-dependent MAPK/ERK1/2-pathway. Lab. Investig. 2012, 92, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Breton, S. The MAPK/ERK-Signaling Pathway Regulates the Expression and Distribution of Tight Junction Proteins in the Mouse Proximal Epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelow, S.; Ahlstrom, R.; Yu, A.S. Biology of claudins. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008, 295, F867–F876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Cell-cell junctions: Structure and regulation in physiology and pathology. Tissue Barriers 2021, 9, 1848212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.; Ragupathy, S.; Borchard, G. Target specific tight junction modulators. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 171, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Tight junctions at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3677–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M. Stress-sensing mechanisms and the physiological roles of the Keap1-Nrf2 system during cellular stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16817–16824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Jin, W.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J.; Oz, F.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effects of Natural Polysaccharides on the Gut Microbiota Related to Human Metabolic Health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e202400792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Wu, Z.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, B.; Sun, B. Protective Effects of Natural Polysaccharides on Intestinal Barrier Injury: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.-J.; Zhou, X.-W. Chinese Cordyceps: Bioactive Components, Antitumor Effects and Underlying Mechanism—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.H.; Zhao, S.; Ho, K.P.; Wu, J.Y. Chemical properties and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides from mycelial culture of Cordyceps sinensis fungus Cs-HK1. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.-L.; Siu, K.-C.; Wang, W.-Q.; Cheung, Y.-C.; Wu, J.-Y. Fractionation, characterization and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides from fermentation broth of a Cordyceps sinensis fungus. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Y.; Dong, Y.-H.; Gu, F.-T.; Zhao, Z.-C.; Huang, L.-X.; Cheng, W.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus Exopolysaccharide on Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB Pathway. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.C.; Gu, F.T.; Li, J.H.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Huang, L.X.; Wu, J.Y. Fractionation, characterization, and assessment of nutritional and immunostimulatory protein-rich polysaccharide-protein complexes isolated from Lentinula edodes mushroom. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Q.; Song, A.X.; Yin, J.Y.; Siu, K.C.; Wong, W.T.; Wu, J.Y. Anti-inflammation activity of exopolysaccharides produced by a medicinal fungus Cordyceps sinensis Cs-HK1 in cell and animal models. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Siu, K.C.; Wang, W.Q.; Liu, X.X.; Wu, J.Y. Structure and antioxidant activity of a novel poly-N-acetylhexosamine produced by a medicinal fungus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramsangtienchai, P.; Sirirak, T.; Seesan, P.; Singrakphon, W.; Padungkasem, J.; Srisook, K.; Watanachote, J. Sulfated polysaccharide from Phyllophorella kohkutiensis: Extraction, purification, and bioactivity assessment. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Hussain, M.; Ni, C.; Jiang, X. Proteolysis and ACE-inhibitory peptide profile of Cheddar cheese: Effect of digestion treatment and different probiotics. LWT 2021, 145, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Xue, S.; Tan, Y.; Zhong, W.; Liang, X.; Wang, J. Binding of Licochalcone A to Whey Protein Enhancing Its Antioxidant Activity and Maintaining Its Antibacterial Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 15917–15927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marullo, S.; Petta, F.; Infurna, G.; Dintcheva, N.T.; D’Anna, F. Polysaccharide-based supramolecular bicomponent eutectogels as sustainable antioxidant materials. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 4513–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.-J.; Udenigwe, C.C.; Aluko, R.E.; Wu, J. Multifunctional peptides from egg white lysozyme. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Rendine, M.; Venturi, S.; Porrini, M.; Gardana, C.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Del Bo, C. Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) preserves intestinal barrier integrity and reduces oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells exposed to a proinflammatory stimulus. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 6943–6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Lu, X.; Liang, X.; Hong, D.; Guan, Z.; Guan, Y.; Zhu, W. Mechanistic studies of the transport of peimine in the Caco-2 cell model. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masungi, C.; Borremans, C.; Willems, B.; Mensch, J.; Van Dijck, A.; Augustijns, P.; Brewster, M.E.; Noppe, M. Usefulness of a novel Caco-2 cell perfusion system. I. In vitro prediction of the absorption potential of passively diffused compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 2507–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Miao, J.; Lou, G. Knockdown of circ-FURIN suppresses the proliferation and induces apoptosis of granular cells in polycystic ovary syndrome via miR-195-5p/BCL2 axis. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błaszczyk, K.; Wilczak, J.; Harasym, J.; Gudej, S.; Suchecka, D.; Królikowski, T.; Lange, E.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Impact of low and high molecular weight oat beta-glucan on oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in spleen of rats with LPS induced enteritis. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 51, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, X.; Siu, K.-C. Isolation and structure characterization of an antioxidative glycopeptide from mycelial culture broth of a medicinal fungus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 17318–17332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, M.L. Chapter 5—UV-absorbance, fluorescence and FT-IR spectroscopy in biopharmaceutical development. In Biophysical Characterization of Proteins in Developing Biopharmaceuticals, 2nd ed.; Houde, D.J., Berkowitz, S.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, M.; Moore, K.J.; Meyer-Almes, F.J.; Guenther, R.; Pope, A.J.; Stoeckli, K.A. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: Lead discovery by miniaturized HTS. Drug Discov. Today 1998, 3, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.J.; Wallace, B.A. Biopharmaceutical applications of protein characterisation by circular dichroism spectroscopy. In Biophysical Characterization of Proteins in Developing Biopharmaceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Bai, C.; Bai, H.; Yang, C.; Tian, L.; Pang, J.; Pang, Z.; Li, D.; Wu, W. Screening of sweet potatoes varieties, physicochemical and biological activity studies of glycoproteins of selected varieties. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, N.J. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2876–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Structural and functional properties of Maillard reaction products of protein isolate (mung bean, Vigna radiate (L.)) with dextran. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Qi, B.; Zhou, L. Relationship between Secondary Structure and Surface Hydrophobicity of Soybean Protein Isolate Subjected to Heat Treatment. J. Chem. 2014, 2014, 475389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, C.; Lee, S.J. Membrane-bound alpha-synuclein has a high aggregation propensity and the ability to seed the aggregation of the cytosolic form. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, M.; Yang, T.; Fang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Zhang, W. Changes in structure and emulsifying properties of coconut globulin after the atmospheric pressure cold plasma treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. A review of NMR analysis in polysaccharide structure and conformation: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nord, L.I.; Vaag, P.; Duus, J.Ø. Quantification of Organic and Amino Acids in Beer by 1H NMR Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 4790–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritota, M.; Marini, F.; Sequi, P.; Valentini, M. Metabolomic characterization of Italian sweet pepper (Capsicum annum L.) by means of HRMAS-NMR spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9675–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Falco, B.; Incerti, G.; Pepe, R.; Amato, M.; Lanzotti, V. Metabolomic Fingerprinting of Romaneschi Globe Artichokes by NMR Spectroscopy and Multivariate Data Analysis. Phytochem. Anal. 2016, 27, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubb, W.A. NMR spectroscopy in the study of carbohydrates: Characterizing the structural complexity. Concepts Magn. Reson. A 2003, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.; Babu, D.; Siraki, A.G. Interactions of the antioxidant enzymes NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and NRH: Quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) with pharmacological agents, endogenous biochemicals and environmental contaminants. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 345, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, B.; Kolli, A.R.; Esch, M.B.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L.; Hickman, J.J. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. J. Lab. Autom. 2015, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, A.; Vollmar, B.; Boros, M.; Menger, M.D. In vivo fluorescence microscopic imaging for dynamic quantitative assessment of intestinal mucosa permeability in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2008, 145, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cor, D.; Knez, Z.; Knez Hrncic, M. Antitumour, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Antiacetylcholinesterase Effect of Ganoderma Lucidum Terpenoids and Polysaccharides: A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.C.-T.; Chang, C.A.; Chiu, K.-H.; Tsay, P.-K.; Jen, J.-F. Correlation evaluation of antioxidant properties on the monosaccharide components and glycosyl linkages of polysaccharide with different measuring methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, J. Chemical properties and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides fractions from mycelial culture of Inonotus obliquus in a ground corn stover medium. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Qu, J.; Tian, X.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Chen, P.; Li, G.; Ma, T. Tailor-made polysaccharides containing uniformly distributed repeating units based on the xanthan gum skeleton. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, J.; Wu, W.; Wen, Y.; Lu, S.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zhao, C. Structure-immunomodulatory activity relationships of dietary polysaccharides. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimgampalle, M.; Chakravarthy, H.; Devanathan, V. Chapter 8—Glucose metabolism in the brain: An update. In Recent Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biochemistry; Viswanath, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bains, K. Protein, lysine and vitamin D: Critical role in muscle and bone health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2548–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Zeng, X.; Qiao, S.; Wu, G.; Li, D. Specific roles of threonine in intestinal mucosal integrity and barrier function. Front. Biosci. 2011, 3, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, D.E.; Shakarjian, M.; Kim, H.D.; Laskin, J.D.; Vetrano, A.M. Mechanisms of oxidant generation by catalase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1203, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.; Chattopadhyay, A. Nrf2-ARE signaling in cellular protection: Mechanism of action and the regulatory mechanisms. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, N.; Nieto-Veloza, A.; Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Si, X.; Tian, J.; Lin, Y.; Jiao, X.; Li, B. Lonicera caerulea polyphenols inhibit fat absorption by regulating Nrf2-ARE pathway mediated epithelial barrier dysfunction and special microbiota. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1309–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Lu, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Ou, X.; Xie, J. Mesona chinensis Benth polysaccharide improves intestinal barrier function in dextran sodium sulfate-induced human Caco-2 cells and its molecular mechanisms. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Accession No. | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZO-1 | NM_003257.4 | CTAAGGGAGCACATGGTGAAGGTAA | GTCGGGCAGAACTTGTATATGGTTT |

| Claudin-1 | NM_021101.6 | GAAGATGAGGATGGCTGTCATTGGG | GGTAAGAGGTTGTTTTTCGGGGAC |

| Occludin | NM_002538.3 | AACTTCGCCTGTGGATGACTTCAG | TTTGACCTTCCTGCTCTTCCCTTTG |

| GAPDH | NM_002046.7 | TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG | TCAAAGGTGGAGGAGTGGGT |

| Total Carbohydrate (%) | Total Protein (%) | MW (Peak Area, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19.29 ± 0.04 | 28.71 ± 0.16 | 2.50 × 104 (41.93%) 1.70 × 103 (53.97%) | |

| Protein structure (chain conformation forms) | |||

| Random: 30.8% | α-Helix: 19.3% | β-Sheet: 49.8% | |

| Monosaccharide composition (molar ratio) | |||

| Mannose: 2.127 | Galactose: 1 | Glucose: 0.4946 | Galactosamine: 0.2688 |

| Essential Amino Acid (EAA) | Non-Essential Amino Acid (NAA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 3.3 ± 0.1 | Alanine | 13.6 ± 0.1 |

| Isoleucine | 6.6 ± 0.1 | Aspartic acid | 43.7 ± 0.1 |

| Leucine | 5.7 ± 0.2 | Arginine | 8.4 ± 0.3 |

| Lysine | 12.4 ± 0.3 | Glutamic acid | 22.2 ± 0.1 |

| Phenylalanine | 7.0 ± 0.2 | Glycine | 21.8 ± 0.1 |

| Threonine | 19.3 ± 0.1 | Serine | 15.5 ± 0.1 |

| Valine | 10.7 ± 0.1 | Tyrosine | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| Proline | 16.5 ± 0.4 | ||

| Total Amino Acids (TAA) | 210.4 ± 1.1 | ||

| Essential Amino Acids (EAA) | 65.0 ± 1.1 | ||

| Non-essential Amino Acids (NAA) | 145.4 ± 0.6 | ||

| TAA (mg/g) = MW/W × V1/V2 × 10 | |||

| Where MW = amino acid MW, W = 100 mg, V1 = 50 mL, and V2 = 20 μL. | |||

| Time (h) | IC50 (ABTS) (mg/mL) ± SEM | IC50 (DPPH) (mg/mL) ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.689 ± 0.032 | 2.023 ± 0.036 |

| 6 | 0.296 ± 0.013 | 1.282 ± 0.032 |

| 12 | 0.34 ± 0.024 | 0.983 ± 0.055 |

| 24 | 0.305 ± 0.015 | 0.807 ± 0.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.Y.; Wu, M.M.H.; Zhao, Z.C.; Gu, F.T.; Huang, L.X.; Kwok, K.W.H.; Wu, J.Y. An Antioxidative Exopolysaccharide–Protein Complex of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus and Its Epithelial Barrier-Protective Effects in Caco-2 Cell Culture. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121501

Zhu YY, Wu MMH, Zhao ZC, Gu FT, Huang LX, Kwok KWH, Wu JY. An Antioxidative Exopolysaccharide–Protein Complex of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus and Its Epithelial Barrier-Protective Effects in Caco-2 Cell Culture. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121501

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yan Yu, Margaret M. H. Wu, Zi Chen Zhao, Fang Ting Gu, Lin Xi Huang, Kevin W. H. Kwok, and Jian Yong Wu. 2025. "An Antioxidative Exopolysaccharide–Protein Complex of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus and Its Epithelial Barrier-Protective Effects in Caco-2 Cell Culture" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121501

APA StyleZhu, Y. Y., Wu, M. M. H., Zhao, Z. C., Gu, F. T., Huang, L. X., Kwok, K. W. H., & Wu, J. Y. (2025). An Antioxidative Exopolysaccharide–Protein Complex of Cordyceps Cs-HK1 Fungus and Its Epithelial Barrier-Protective Effects in Caco-2 Cell Culture. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121501