EFNA5 as an Oocyte-Derived Factor Enhances Developmental Competence by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis During In Vitro Maturation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Oocyte Collection and In Vitro Maturation

2.3. In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Culture

2.4. Evaluation of COCs’ Expansion

2.5. Detection of Apoptosis

2.6. Measurement of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Glutathione (GSH) Levels

2.7. Lipid Peroxidation

2.8. γH2AX Staining

2.9. Cortical Granule Staining

2.10. Immunofluorescence Localization of EFNA5 and EPHA4

2.11. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

2.12. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.13. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Expression Pattern of EFNA5 and EPHA4 in Ovine COCs

3.2. EFNA5 Enhances In Vitro-Matured Oocyte Developmental Potential

3.3. EFNA5 Enhances Maturation Status of COCs

3.4. Effects of EFNA5 on the Transcriptional Profile of Oocytes Matured In Vitro

3.5. EFNA5 Enhances Oocyte Redox Homeostasis

3.6. EFNA5 Alters the Transcriptional Profile of Cumulus Cells

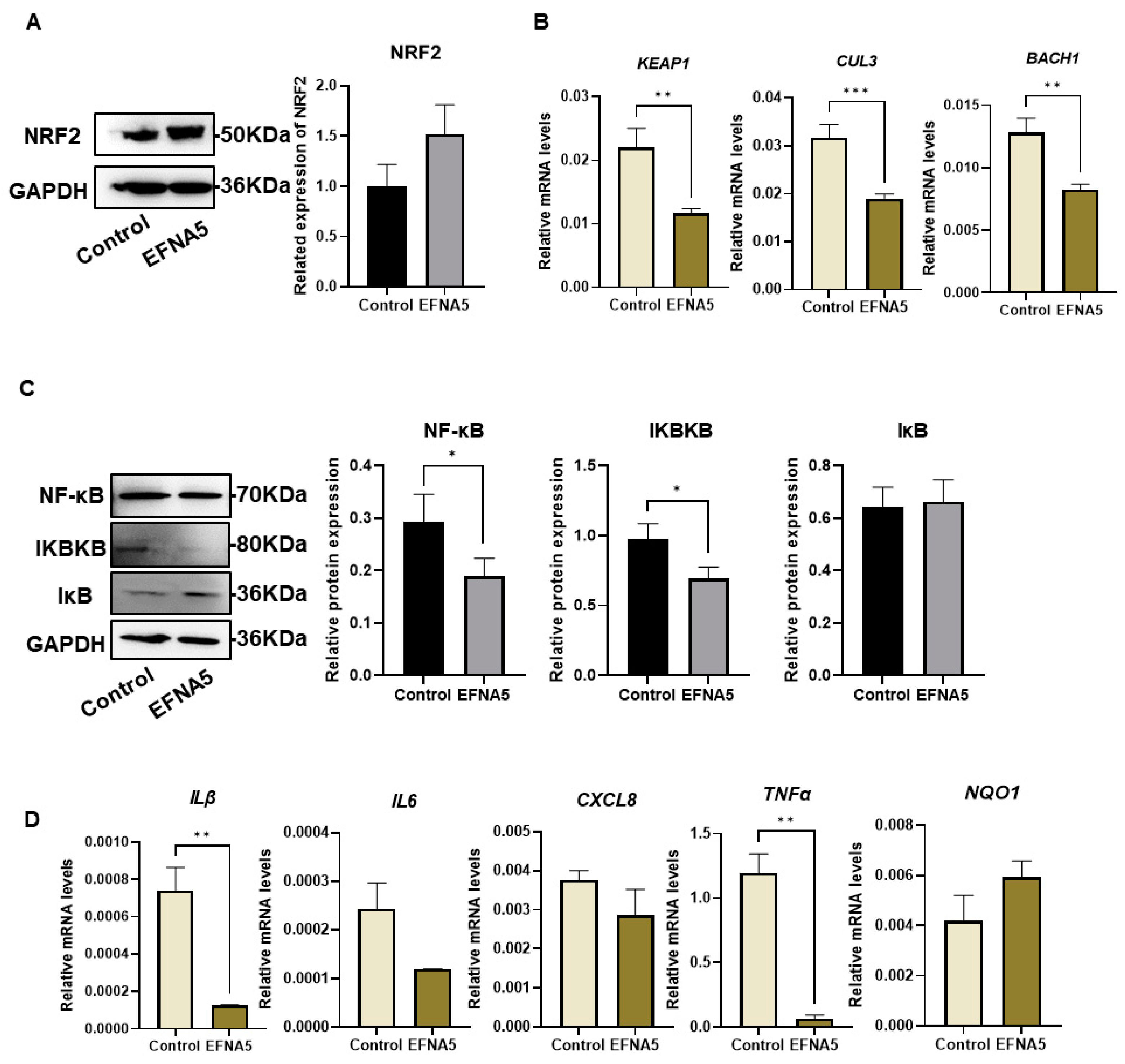

3.7. EFNA5 Regulates NRF2 and NF-κB Signaling in COCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mostinckx, L.; Goyens, E.; Mackens, S.; Roelens, C.; Boudry, L.; Uvin, V. Clinical outcomes from ART in predicted hyperresponders: In vitro maturation of oocytes versus conventional ovarian stimulation for IVF/ICSI. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, K.M.; Thompson, J.G. In vitro maturation of mammalian oocytes: Outcomes and consequences. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2008, 26, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, M.; Grynberg, M.; Ho, T.M.; Yuan, Y.; Albertini, D.F.; Gilchrist, R.B. Perspectives on the development and future of oocyte IVM in clinical practice. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppig, J.J.; O’Brien, M.J.; Wigglesworth, K.; Nicholson, A.; Zhang, W.; King, B.A. Effect of in vitro maturation of mouse oocytes on the health and lifespan of adult offspring. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chian, R.; Li, J.; Lim, J.; Yoshida, H. IVM of human immature oocytes for infertility treatment and fertility preservation. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2023, 22, e12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R.B.; Thompson, J.G. Oocyte maturation: Emerging concepts and technologies to improve developmental potential in vitro. Theriogenology 2007, 67, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Albertini, D.F. The road to maturation: Somatic cell interaction and self-organization of the mammalian oocyte. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, R.B.; Lane, M.; Thompson, J.G. Oocyte-secreted factors: Regulators of cumulus cell function and oocyte quality. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 14, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wu, X.; O’Brien, M.J.; Pendola, F.L.; Denegre, J.N.; Matzuk, M.M. Synergistic roles of BMP15 and GDF9 in the development and function of the oocyte–cumulus cell complex in mice: Genetic evidence for an oocyte—Granulosa cell regulatory loop. Dev. Biol. 2004, 276, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulini, F.; Melo, E.O. The role of oocyte secreted factors GDF9 and BMP15 in follicular development and oogenesis. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2011, 46, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Otsuka, F.; Nakamura, E.; Inagaki, K.; Ogura-Ochi, K.; Tsukamoto, N. Regulatory role of kit ligand–kit interaction and oocyte factors in steroidogenesis by rat granulosa cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 358, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; You, L.; Wang, S.; Bie, J.; Su, Z. RSPO2 coordinates with GDF9: BMP15 heterodimers to promote granulosa cell and oocyte development in mice. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, S. Intercellular communication in the cumulus–oocyte complex during folliculogenesis: A review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1137787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, Q. Role of EFNAs in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment and their impact on pancreatic adenocarcinoma prognosis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2025, 17, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Feng, X.; Cui, Y.; Wang, L.; Gan, J.; Zhao, Y. Expression characteristic, immune signature, and prognosis value of EFNA family identified by multi-omics integrative analysis in pan-cancer. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buensuceso, A.V.; Son, A.I.; Zhou, R.; Paquet, M.; Withers, B.M.; Deroo, B.J. Ephrin-A5 is required for optimal fertility and a complete ovulatory response to gonadotropins in the female mouse. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Worku, T.; Wang, K.; Ayers, D.; Wu, D.; Ur Rehman, Z.; Zhou, H. Regulatory roles of ephrinA5 and its novel signaling pathway in mouse primary granulosa cell apoptosis and proliferation. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.; Li, K.; Yang, K.; Gao, G.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X. Genome-wide association study reveals novel candidate genes influencing semen traits in Landrace pigs. Animals 2024, 14, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.; Lledó, B.; Ortiz, J.A.; Lozano, F.M.; García, E.M.; Bernabeu, A. Identification of new variants and candidate genes in women with familial premature ovarian insufficiency using whole-exome sequencing. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzirodos, N.; Irving-Rodgers, H.F.; Hummitzsch, K.; Harland, M.L.; Morris, S.E.; Rodgers, R.J. Transcriptome profiling of granulosa cells of bovine ovarian follicles during growth from small to large antral sizes. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhyden, B.C.; Caron, P.J.; Buccione, R.; Eppig, J.J. Developmental pattern of the secretion of cumulus expansion-enabling factor by mouse oocytes and the role of oocytes in promoting granulosa cell differentiation. Dev. Biol. 1990, 140, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Ng, J.; Liao, J.; Luk, A.C.; Suen, A.; Chan, T. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies molecular targets associated with poor in vitro maturation performance of oocytes collected from ovarian stimulation. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1907–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Ju, J.; Pan, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, S. Increased environment-related metabolism and genetic expression in the in vitro matured mouse oocytes by transcriptome analysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Bian, X.; Sun, Q. Nuclear transfer improves the developmental potential of embryos derived from cytoplasmic deficient oocytes. iScience 2023, 26, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.M.; Silva, E.; Chitwood, J.L.; Schoolcraft, W.B.; Krisher, R.L.; Ross, P.J. Differing molecular response of young and advanced maternal age human oocytes to IVM. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Lee, T. Aging-related aneuploidy is associated with mitochondrial imbalance and failure of spindle assembly. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.M.; Chitwood, J.L.; Ross, P.J. RNA-seq profiling of single bovine oocyte transcript abundance and its modulation by cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 82, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liang, H.; Wu, Z.; Huo, L.; Du, Z. Identification of lncRNAs involved in maternal–zygotic transition of in vitro produced porcine embryos by single-cell RNA-seq. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2022, 57, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopps, E.; Noto, D.; Caimi, G.; Averna, M.R. A novel component of the metabolic syndrome: The oxidative stress. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaka, M.; Tajima, K.; Tsang, B.K.; Kotsuji, F. Oocyte–granulosa–theca cell interactions during preantral follicular development. J. Ovarian Res. 2009, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangas, S.A.; Matzuk, M.M. The art and artifact of GDF9 activity: Cumulus expansion and the cumulus expansion-enabling factor. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 73, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Juengel, J.L.; Hudson, N.L.; Heath, D.A.; Smith, P.; Reader, K.L.; Lawrence, S.B. Growth differentiation factor 9 and bone morphogenetic protein 15 are essential for ovarian follicular development in sheep. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 67, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisabeth, E.M.; Falivelli, G.; Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a009159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Patel, O.; Janes, P.W.; Murphy, J.M.; Lucet, I.S. Eph receptor signalling: From catalytic to non-catalytic functions. Oncogene 2019, 38, 6567–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, K.; Karikis, I.; Byrd, C.; Sanidas, G.; Wolff, N.; Triantafyllou, M. Eph/ephrin-mediated immune modulation: A potential therapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1523456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomé, A.; Suda, N.; Yu, J.; Zhu, C.; Son, J.; Ding, H. Notch-mediated Ephrin signaling disrupts islet architecture and cell function. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e157694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, J.; Schell, B.; Nasser, H.; Rachid, M.; Ruaud, L.; Couque, N. EPHA7 haploinsufficiency is associated with a neurodevelopmental disorder. Clin. Genet. 2021, 100, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNatty, K.P.; Juengel, J.L.; Wilson, T.; Galloway, S.M.; Davis, G.H.; Hudson, N.L. Oocyte-derived growth factors and ovulation rate in sheep. Reproduction 2003, 61, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juengel, J.L.; Hudson, N.L.; Berg, M.; Hamel, K.; Smith, P.; Lawrence, S.B. Effects of active immunization against growth differentiation factor 9 and/or bone morphogenetic protein 15 on ovarian function in cattle. Reproduction 2009, 138, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li-Ling, J.; Xiong, D.; Wei, J.; Zhong, T.; Tan, H. Age-related decline in the expression of GDF9 and BMP15 genes in follicle fluid and granulosa cells derived from poor ovarian responders. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, R.; Ferrari, I.; Bestetti, I.; Moleri, S.; Brancati, F.; Petrone, L. Fundamental role of BMP15 in human ovarian folliculogenesis revealed by null and missense mutations associated with primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2020, 41, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirard, M.; Richard, F.; Blondin, P.; Robert, C. Contribution of the oocyte to embryo quality. Theriogenology 2006, 65, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerin, P.; El Mouatassim, S.; Menezo, Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Hum. Reprod. Update 2001, 7, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, R.K. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2005, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizos, D.; Ward, F.; Duffy, P.; Boland, M.P.; Lonergan, P. Consequences of bovine oocyte maturation, fertilization or early embryo development in vitro versus in vivo: Implications for blastocyst yield and blastocyst quality. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2002, 61, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromfield, J.J.; Sheldon, I.M. Lipopolysaccharide initiates inflammation in bovine granulosa cells via the TLR4 pathway and perturbs oocyte meiotic progression in vitro. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 5029–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Huang, L.; Tang, X.; Li, J.; Li, X. EphrinA5 is involved in retinal neovascularization in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7161027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, L.; Oeckl, P.; Timmers, M.; Lenaerts, A.; van der Vos, J.; Smolders, S. Reduction of ephrin-A5 aggravates disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, A.; Blaschuk, O.W.; Dinh, D.T.; McPhee, T.; Becker, R.; Abell, A.D. N-cadherin mechanosensing in ovarian follicles controls oocyte maturation and ovulation. eLife 2025, 13, RP92068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turathum, B.; Gao, E.; Chian, R. The function of cumulus cells in oocyte growth and maturation and in subsequent ovulation and fertilization. Cells 2021, 10, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, A.; Robbins, S.M. EphrinA5 modulates cell adhesion and morphology in an integrin-dependent manner. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5396–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, G.; Kästner, B.; Weth, F.; Bolz, J. Multiple effects of ephrin-A5 on cortical neurons are mediated by SRC family kinases. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5643–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Cui, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; An, L.; Tian, J.; Xi, G. EFNA5 as an Oocyte-Derived Factor Enhances Developmental Competence by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis During In Vitro Maturation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121476

Liu X, Cui J, Wang Y, Hao J, Wu Y, Wang Y, An L, Tian J, Xi G. EFNA5 as an Oocyte-Derived Factor Enhances Developmental Competence by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis During In Vitro Maturation. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121476

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xingyuan, Jian Cui, Yubing Wang, Jia Hao, Yingjie Wu, Yinjuan Wang, Lei An, Jianhui Tian, and Guangyin Xi. 2025. "EFNA5 as an Oocyte-Derived Factor Enhances Developmental Competence by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis During In Vitro Maturation" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121476

APA StyleLiu, X., Cui, J., Wang, Y., Hao, J., Wu, Y., Wang, Y., An, L., Tian, J., & Xi, G. (2025). EFNA5 as an Oocyte-Derived Factor Enhances Developmental Competence by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis During In Vitro Maturation. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121476