The Effect of Newly Designed High-Antioxidant Food Products on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prototype Design of New Antioxidant Bars

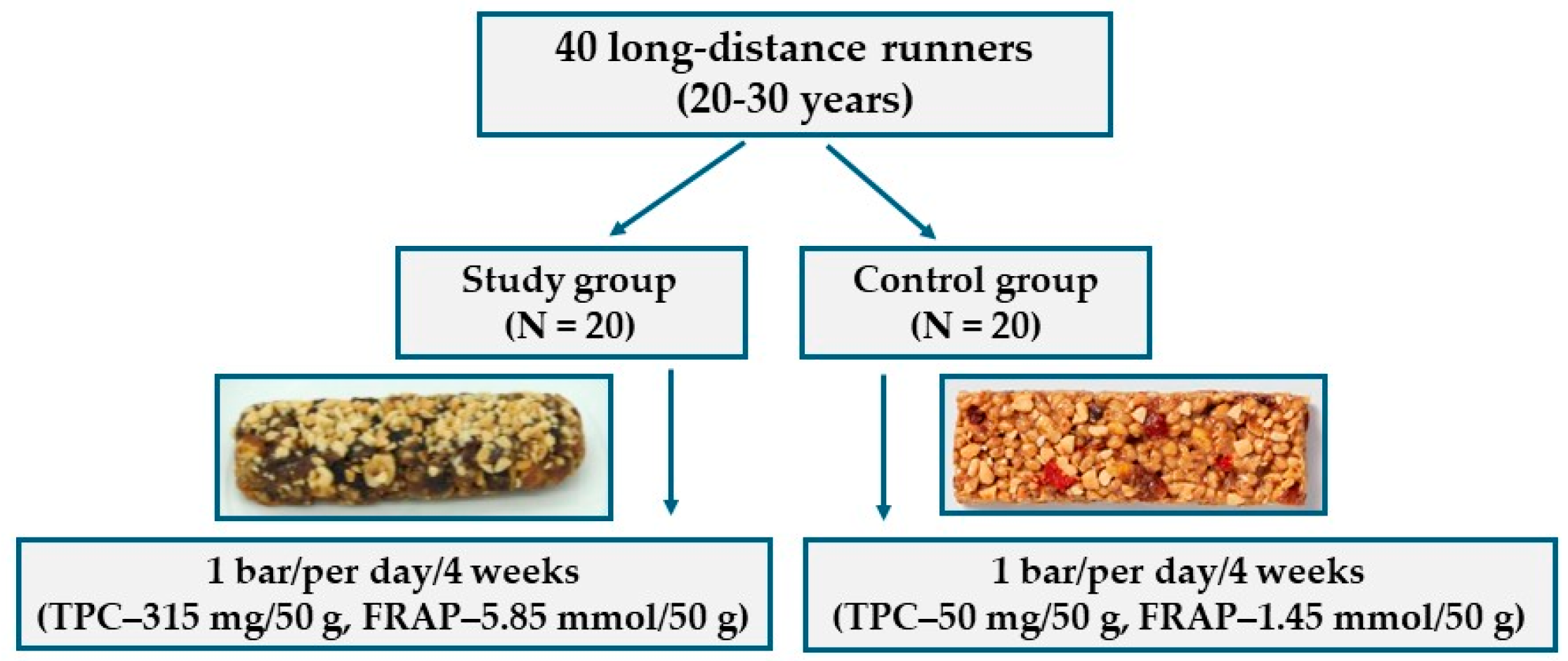

2.2. Study Population and Intervention

2.3. Antioxidant and Oxidative Stress Markers

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional and Antioxidant Value of the Bars

3.2. Consumer Acceptability of the Bars

3.3. Study Population and Intervention Study

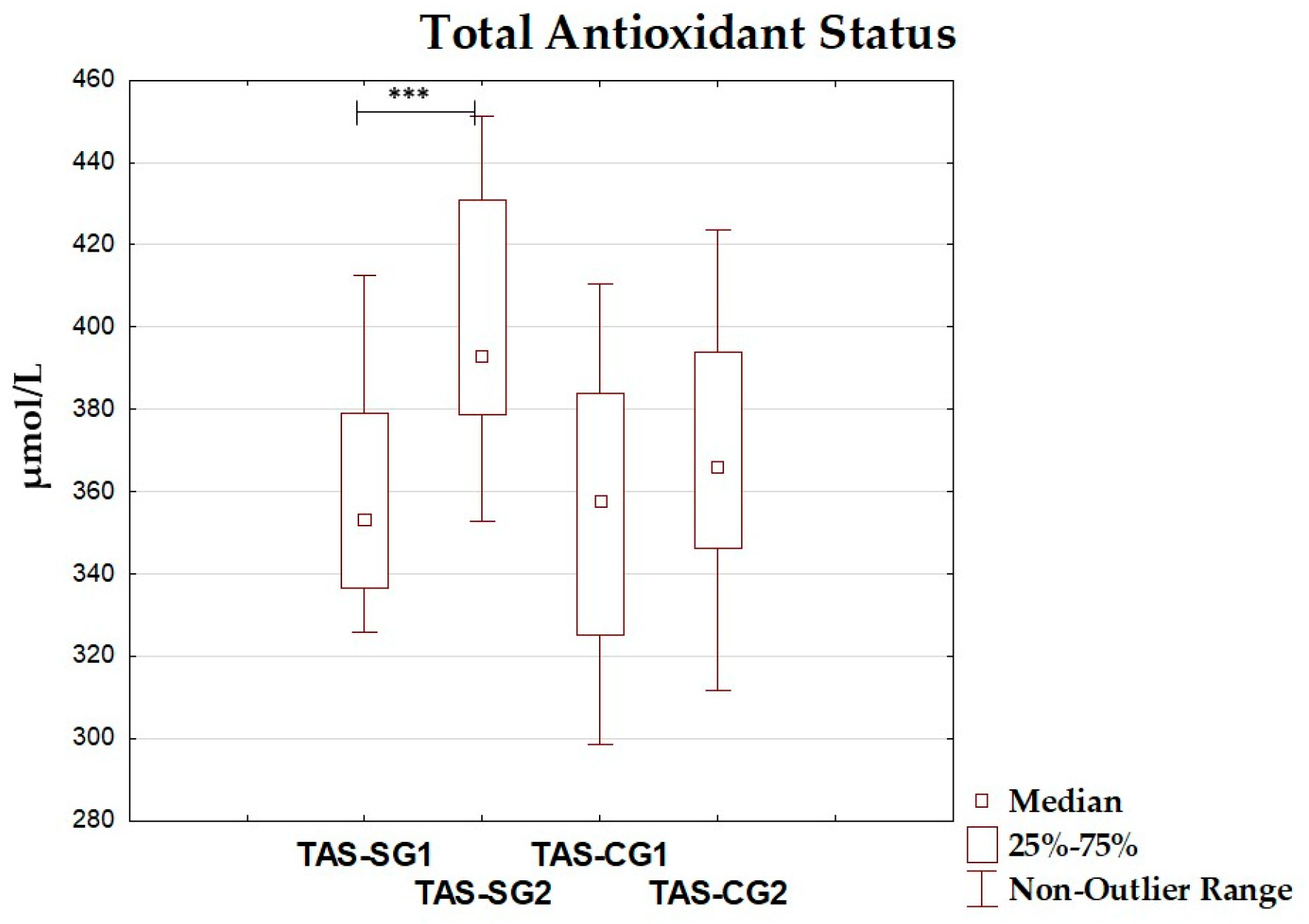

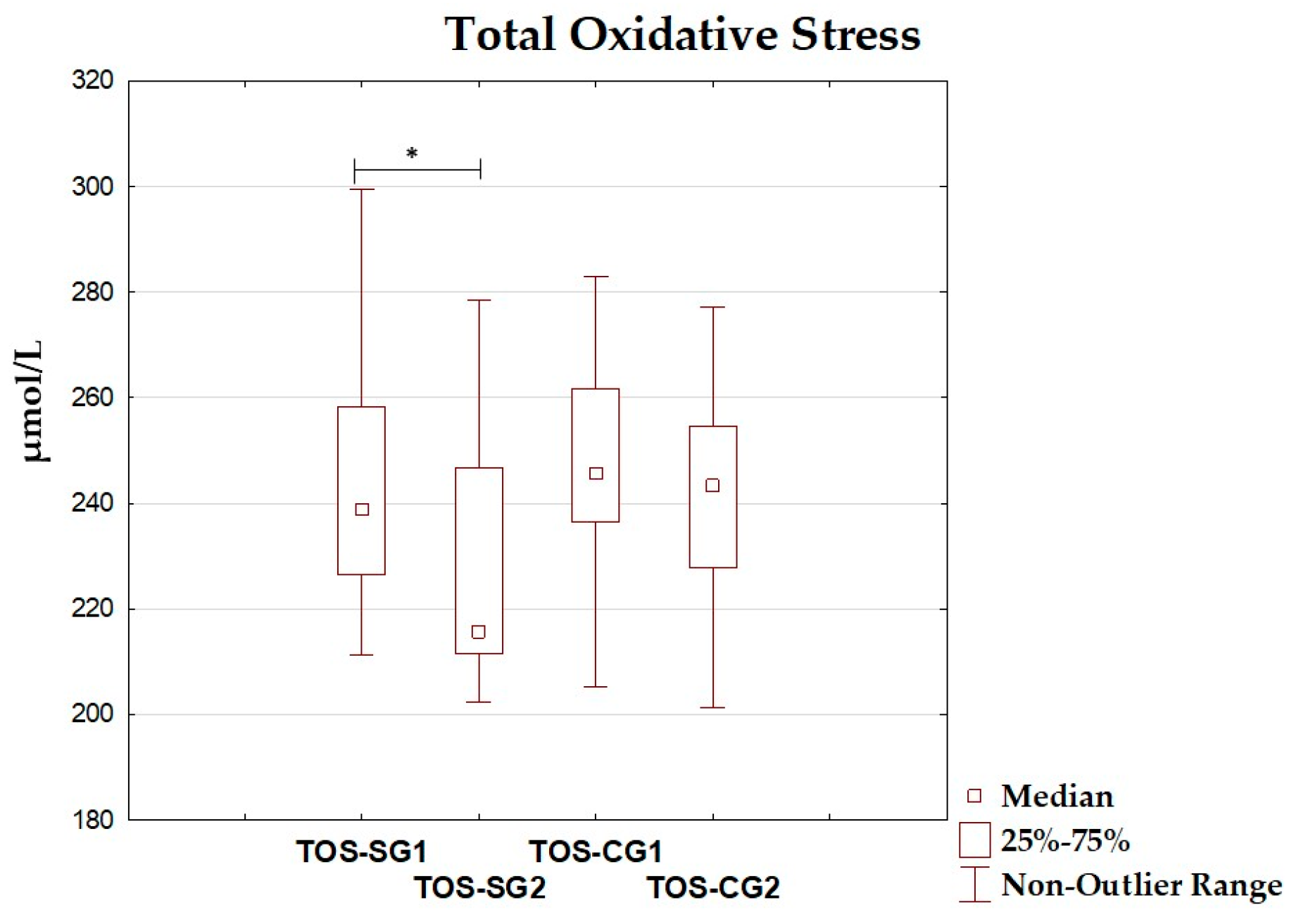

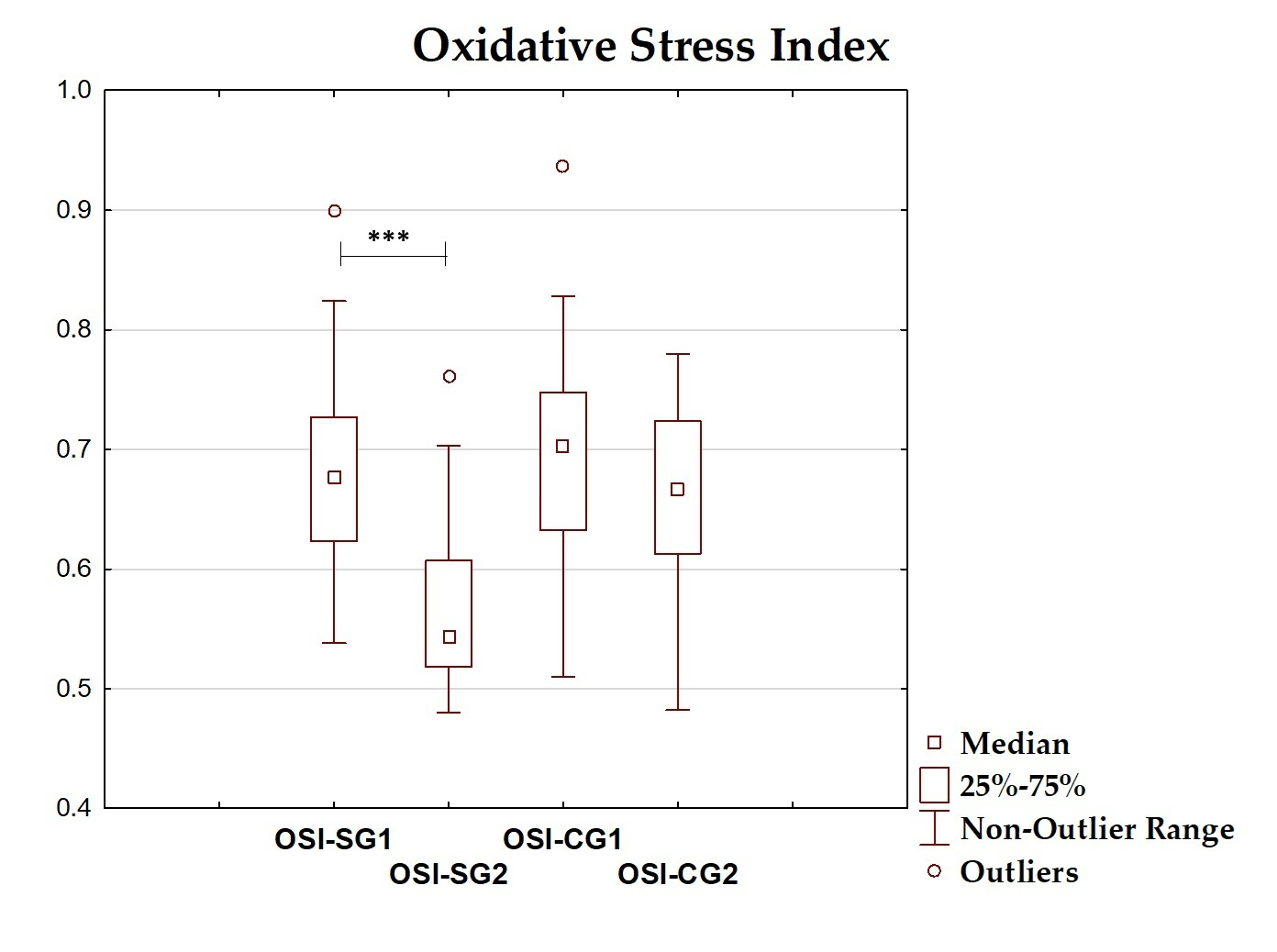

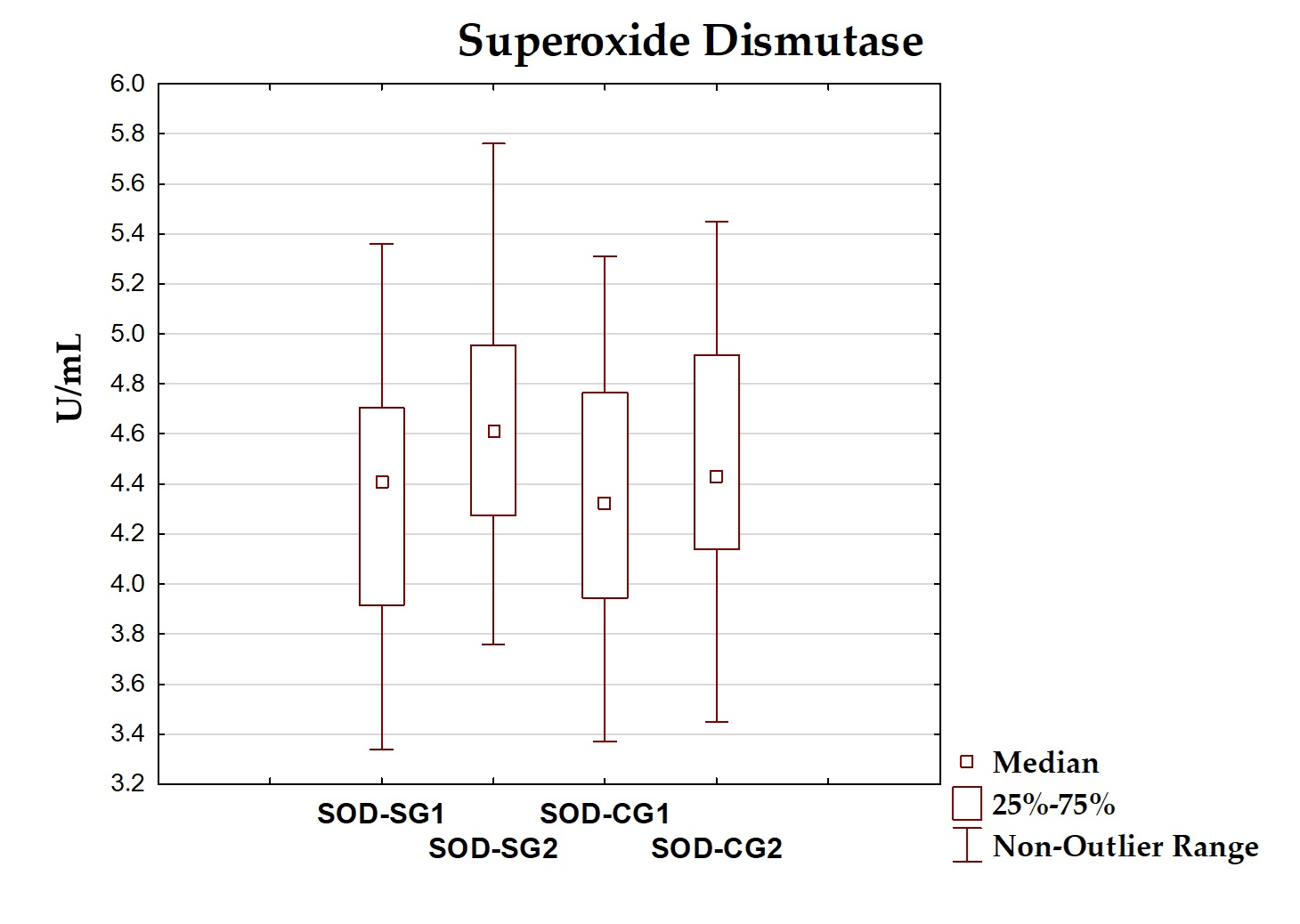

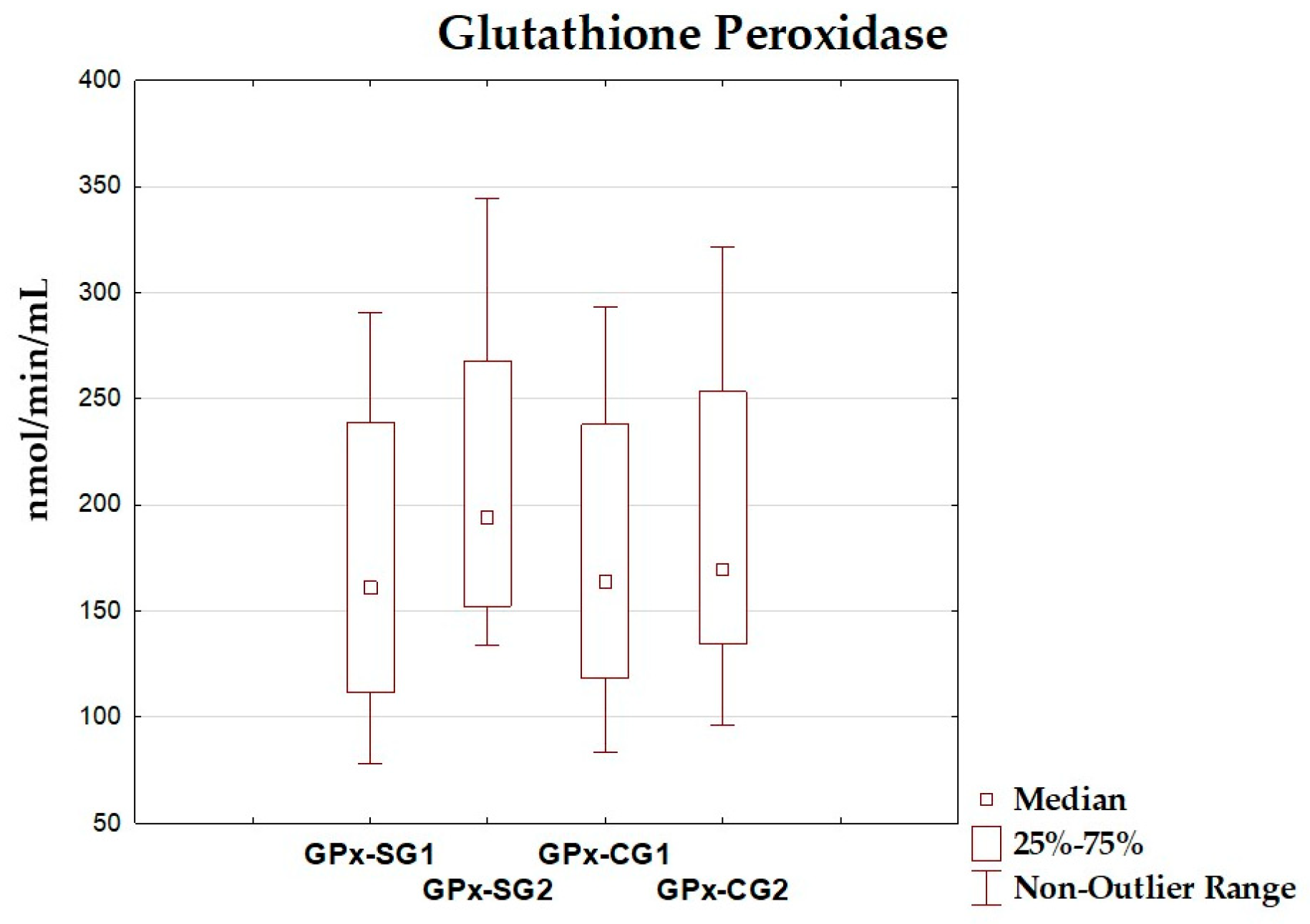

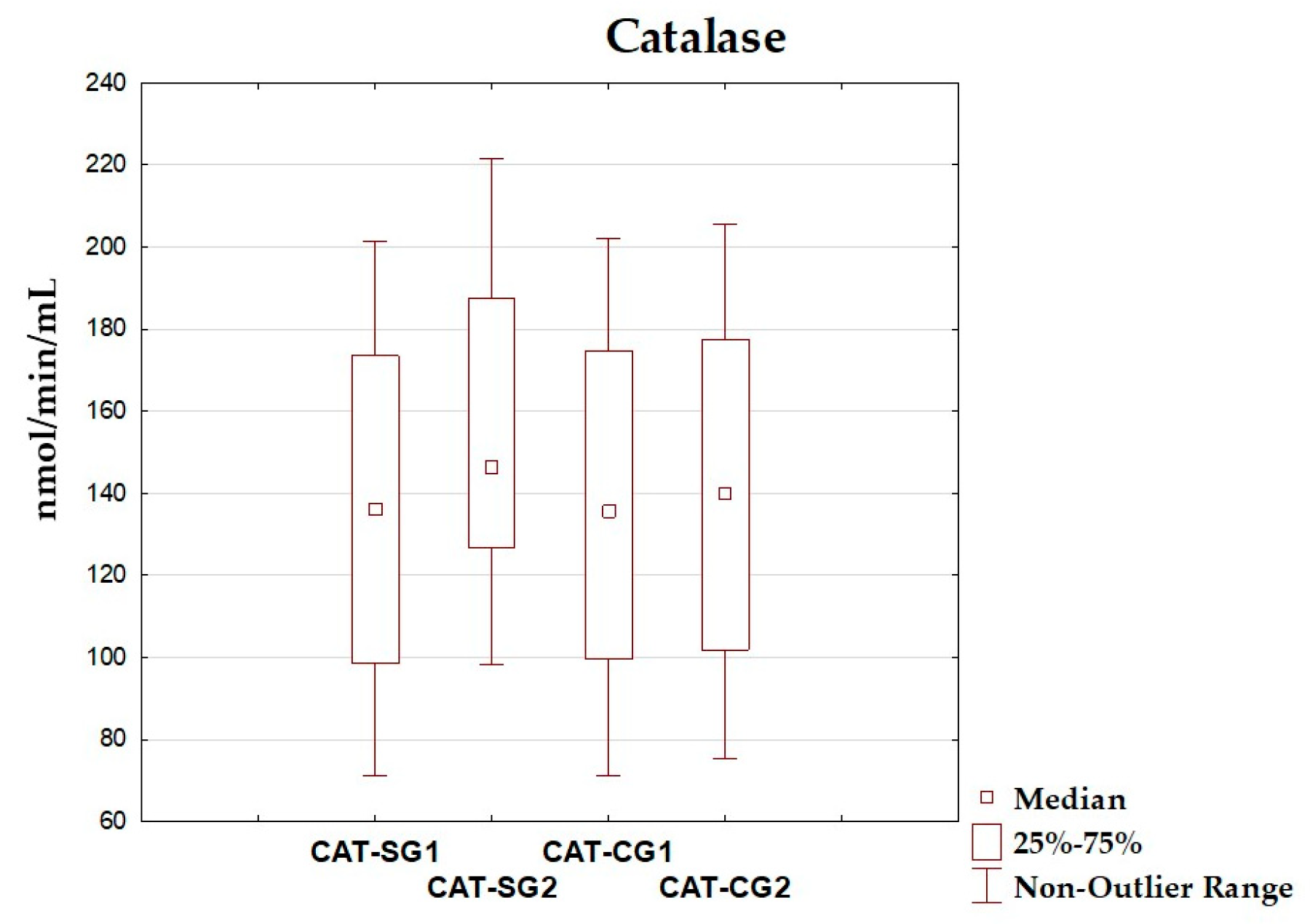

3.4. Oxidative–Antioxidant Markers Before and After Intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarkson, P.M.; Thompson, H.S. Antioxidants: What role do they play in physical activity and health? Am. J. Clin Nutr. 2000, 72 (Suppl. S2), 637S–6346S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, K.G.; Asif, I.M.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Owens, D.S.; Prutkin, J.M.; Salerno, J.C.; Zigman, M.L.; Ellenbogen, R.; Rao, A.L.; Ackerman, M.J.; et al. Incidence, cause, and comparative frequency of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes: A decade in review. Circulation 2015, 132, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zujko-Kowalska, K.; Kamiński, K.A.; Małek, Ł. Detraining among athletes—Is withdrawal of adaptive cardiovascular changes a hint for the differential diagnosis of physically active people? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarczuk, A.; Dzitkowska-Zabielska, M. Polyphenol supplementation and antioxidant status in athletes: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, S.; Guglielmetti, M.; Neri, L.C.L.; Correale, L.; Tagliabue, A.; Ferraris, C. Mediterranean diet and athletic performance in elite and competitive athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeini, A.A.; Rahnama, N.; Hamedinia, M.R. Effects of vitamin E supplementation on oxidative stress at rest and after exercise to exhaustion in athletic students. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness. 2006, 46, 458–461. [Google Scholar]

- Popovic, L.M.; Mitic, N.R.; Miric, D.; Bisevac, B.; Miric, M.; Popovic, B. Influence of vitamin C supplementation on oxidative stress and neutrophil inflammatory response in acute and regular exercise. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 295497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Li, Z.; Kim, J.C. Effects of flavonoid supplementation on athletic performance in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peternelj, T.T.; Coombes, J.S. Antioxidant supplementation during exercise training: Beneficial or detrimental? Sports Med. 2011, 41, 1043–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, A.; Javadi, M.; Mirmiran, P.; Bahadoran, Z. Exercise-induced oxidative stress and dietary antioxidants. Asian J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, e24898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.D.; Bock, P.M.; Becker, G.F.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Bello-Klein, A.; Oliveira, A.R. Comparison of the effects of two antioxidant diets on oxidative stress markers in triathletes. Biol. Sport. 2018, 35, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devrim-Lanpir, A.; Bilgic, P.; Kocahan, T.; Deliceoğlu, G.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Total dietary antioxidant intake including polyphenol content: Is it capable to fight against increased oxidants within the body of ultra-endurance athletes? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnulty, S.R.; McAnulty, L.S.; Nieman, D.C.; Dumke, C.L.; Morrow, J.D.; Utter, A.C.; Henson, D.A.; Proulx, W.R.; George, G.L. Consumption of blueberry polyphenols reduces exercise-induced oxidative stress compared to vitamin C. Nutr. Res. 2004, 24, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupina, S.; Fields, C.; Roman, M.C.; Brunelle, S.L. Determination of total phenolic content using the Folin-C Assay: Single-Laboratory Validation, First Action 2017.13. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zujko, M.E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Piotrowski, W.; Terlikowska, K.M. Dietary antioxidant capacity of the patients with cardiovascular disease in a cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, V.; Perez-Jiménez, J.; Vos, F.; Crespy, V.; du Chaffaut, L.; Mennen, L.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Cruz, J.; Wishart, D.; et al. Phenol-Explorer: An online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database 2010, 2010, bap024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, M.H.; Halvorsen, B.L.; Holte, K.; Bøhn, S.K.; Dragland, S.; Sampson, L.; Willey, C.; Senoo, H.; Umezono, Y.; Sanada, C.; et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, E.; Stoś, K.; Woźniak, A.; Mojska, H. Nutritional Standards for the Polish Population; (In Polish). National Institute of Public Health PZH—National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; pp. 433–455. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W.; Radák, Z.; Gu, Y. Harmony in motion: Unraveling the nexus of sports, plant-based nutrition, and antioxidants for peak performance. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dion, S.; Walker, G.; Lambert, K.; Stefoska-Needham, A.; Craddock, J.C. The diet quality of athletes as measured by diet quality indices: A scoping review. Nutrients 2024, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EC) no 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006R1924 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Zupo, R.; Castellana, F.; Lisco, G.; Corbo, F.; Crupi, P.; Sardone, R.; Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Rondanelli, M.; Clodoveo, M.L. Dietary intake of polyphenols and all-cause mortality: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Metabolites 2024, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Liao, L.M.; Sinha, R.; Chun, O.K. Dietary total antioxidant capacity, a diet quality index predicting mortality risk in US adults: Evidence from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Haumont, M.; Prost-Camus, E.; Durand, P.; Prost, M.; Lizard, G.; Latruffe, N. Protection of C2C12 skeletal muscle cells toward oxidation by a polyphenol-rich plant extract. Redox Exp. Med. 2023, 1, e230002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, V.; Labbé, J.; Deckert, V.; Pais de Barros, J.P.; Boidot, R.; Haumont, M.; Maquart, G.; Le Guern, N.; Masson, D.; Prost-Camus, E.; et al. Healthy adiposity and extended lifespan in obese mice fed a diet supplemented with a polyphenol-rich plant extract. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary polyphenols and their role in oxidative stress-induced human diseases: Insights into protective effects, antioxidant potentials and mechanism(s) of action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Feng, H.; Li, C.; Jia, F.; Zhang, X. The mutual effect of dietary fiber and polyphenol on gut microbiota: Implications for the metabolic and microbial modulation and associated health benefits. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 358, 123541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Raza, S.T.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmad, A.; Abbas, S.; Mahdi, F. The role of vitamin E in human health and some diseases. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2014, 14, e157–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Jang, J.Y.; Baik, S.M. Selenium as an antioxidant: Roles and clinical applications in critically Ill and trauma patients: A narrative review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wąsowicz, W.; Gromadzińska, J.; Rydzyński, K.; Tomczak, J. Selenium status of low-selenium area residents: Polish experience. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 137, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepeda, V.; Ródenas-Munar, M.; García, S.; Bouzas, C.; Tur, J.A. Unlocking the power of magnesium: A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding its role in oxidative stress and inflammation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaamouri, N.; Zouhal, H.; Suzuki, K.; Hammami, M.; Ghaith, A.; El Mouhab, E.H.; Hackney, A.C.; Laher, I.; Ounis, O.B. Effects of carob rich-polyphenols on oxidative stress markers and physical performance in taekwondo athletes. Biol. Sport. 2024, 41, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A.; Hashimoto, S.; Suzuki, M.; Ueno, H.; Sugita, M. Oligomerized polyphenols in lychee fruit extract supplements may improve high-intensity exercise performance in male athletes: A pilot study. Phys. Act. Nutr. 2021, 25, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valder, S.; Habersatter, E.; Kostov, T.; Quenzer, S.; Herzig, L.; von Bernuth, J.; Matits, L.; Herdegen, V.; Diel, P.; Isenmann, E. The influence of a polyphenol-rich red berry fruit juice on recovery process and leg strength capacity after six days of intensive endurance exercise in recreational endurance athletes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, E.; Erbasan, H.; Riso, P.; Perna, S. Impact of the Mediterranean diet on athletic performance, muscle strength, body composition, and antioxidant markers in both athletes and non-professional athletes: A systematic review of intervention trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska-Krępa, E.; Bańkowski, S.; Kargul, A.; Iskra, J. Changes in blood antioxidant status in American football players and soccer players over a training macrocycle. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Units | Bar No. 1 | Bar No. 2 | Bar No. 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | kcal/100 g | 434 | 458 | 308 |

| Protein | g/100 g | 10.4 | 12.0 | 2.9 |

| Carbohydrates | g/100 g | 47.2 | 40.2 | 69.6 |

| Dietary fiber | g/100 g | 9.9 | 7.8 | 6.1 |

| Fat | g/100 g | 20.4 | 28.4 | 0.6 |

| SFA | g/100 g | 1.8 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| MUFA | g/100 g | 11.7 | 16.3 | 0.2 |

| PUFA | g/100 g | 6.8 | 7.8 | 0.2 |

| Zinc | mg/100 g | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| Phosphorus | mg/100 g | 218 | 257 | 49.5 |

| Magnesium | mg/100 g | 120 | 135 | 51.8 |

| Potassium | mg/100 g | 521 | 544 | 635 |

| Selenium | µg/100 g | 7.43 | 22.3 | 2.5 |

| Calcium | mg/100 g | 114 | 99.1 | 55.3 |

| Iron | mg/100 g | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| Vitamin B1 | mg/100 g | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0.08 |

| Vitamin B2 | mg/100 g | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.1 |

| Vitamin B3 | mg/100 g | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Vitamin B9 | µg/100 g | 14.7 | 10.4 | 9.4 |

| Vitamin E | mg/100 g | 5.4 | 8.4 | 1.0 |

| TPC | mg GAE/100 g | 546 | 630 | 385 |

| FRAP | mmol/100 g | 8.4 | 11.7 | 5.2 |

| Scale | Range | Bar No. 1 | Bar No. 2 | Bar No. 3 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic scale | 1–8 | ||||

| Taste | 7.37 ± 0.53 | 7.30 ± 0.64 | 7.05 ± 0.84 | 0.045 (1,2/3) | |

| Overall rating | 7.32 ± 0.47 | 7.32 ± 0.59 | 6.97 ± 0.76 | 0.039 (1,2/3) | |

| Intention to purchase | 1–5 | 4.62 ± 0.35 | 4.55 ± 0.41 | 4.20 ± 0.74 | 0.027 (1,2/3) |

| Characteristics | Total | Study Group | Control Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample number | 40 | 20 | 20 | - |

| Age, years | 24.4 ± 5.3 | 24.8 ± 4.7 | 23.9 ± 5.6 | 0.723 |

| Gender (men), N (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| Higher education, N (%) | 82.5 | 85 | 80 | 0.644 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 1.9 | 23.7 ± 1.6 | 22.9 ± 2.3 | 0.572 |

| Variables | SG Before | SG After | p | CG Before | CG After | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 2465 ± 414 | 2512 ± 494 | 0.341 | 2410 ± 562 | 2548 ± 470 | 0.561 |

| Protein (g) | 92.6 ± 12.7 | 90.4 ± 17.3 | 0.423 | 88.9 ± 19.5 | 90.3 ± 15.2 | 0.385 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 324.3 ± 45.5 | 343.4 ± 54.2 | 0.092 | 295.7 ± 35.2 | 320.3 ± 42.1 | 0.113 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 24.3 ± 8.4 | 23.8 ± 9.2 | 0.655 | 24.5 ± 7.2 | 24.1 ± 8.6 | 0.726 |

| Fat (g) | 83.4 ± 24.2 | 78.3 ± 26.6 | 0.543 | 85.7 ± 22.9 | 82.9 ± 25.3 | 0.584 |

| SFA (g) | 24.4 ± 11.5 | 23.8 ± 12.1 | 0.241 | 23.5 ± 12.7 | 24.1 ± 12.5 | 0.183 |

| MUFA (g) | 31.4 ± 11.7 | 32.1 ± 12.5 | 0.523 | 29.5 ± 12.9 | 32.8 ± 13.7 | 0.127 |

| PUFA (g) | 13.2 ± 5.8 | 12.8 ± 4.7 | 0.146 | 13.5 ± 6.1 | 13.7 ± 6.8 | 0.454 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 465.3 ± 88.2 | 446.8 ± 85.3 | 0.352 | 446.2 ± 98.7 | 428.1 ± 91.5 | 0.148 |

| Zinc (mg) | 11.3 ± 4.8 | 10.8 ± 4.2 | 0.395 | 11.5 ± 3.9 | 10.4 ± 3.7 | 0.092 |

| Iron (mg) | 12.2 ± 6.8 | 13.2 ± 7.6 | 0.144 | 12.6 ± 7.1 | 13.5 ± 8.2 | 0.122 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 105.2 ± 63.7 | 101.9 ± 70.4 | 0.321 | 103.3 ± 75.8 | 106.2 ± 77.6 | 0.246 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 11.4 ± 5.6 | 12.1 ± 6.3 | 0.286 | 11.8 ± 6.7 | 12.7 ± 7.4 | 0.183 |

| Vitamin A (mg) | 1125 ± 487 | 1231 ± 423 | 0.164 | 1096 ± 459 | 1198 ± 511 | 0.086 |

| Vitamin D (µg) | 5.3 ± 3.4 | 5.8 ± 4.1 | 0.113 | 5.1 ± 3.9 | 5.5 ± 4.4 | 0.144 |

| TPC (mg) | 2311 ± 643 | 2287 ± 711 | 0.321 | 2365 ± 574 | 2295 ± 624 | 0.286 |

| FRAP (mmol) | 15.3 ± 7.1 | 14.6 ± 7.5 | 0.487 | 15.8 ± 6.9 | 14.9 ± 6.7 | 0.382 |

| Variables | Study Group Before Intervention | Study Group After Intervention | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | Me (IQR) | M ± SD | Me (IQR) | ||

| TAS (µmol/L) | 359.60 ± 28.21 | 353.21 (336.43–378.97) | 401.98 ± 32.21 | 392.82 (378.83–430.78) | <0.001 |

| TOS (µmol/L) | 244.72 ± 25.21 | 238.93 (226.47–258.29) | 227.54 ± 22.87 | 215.55 (211.46–246.77) | 0.029 |

| OSI | 0.686 ± 0.089 | 0.677 (0.623–0.727) | 0.569 ± 0.076 | 0.544 (0.519–0.607) | <0.001 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 4.318 ± 0.572 | 4.410 (3.915–4.705) | 4.646 ± 0.559 | 4.610 (4.275–4.955) | 0.075 |

| GPx (nmol/min/mL) | 171.73 ± 71.29 | 161.15 (111.54–238.99) | 210.65 ± 66.47 | 194.60 (152.37–267.60) | 0.082 |

| CAT (nmol/min/mL) | 135.06 ± 41.85 | 135.98 (98.58–173.43) | 157.15 ± 37.85 | 146.54 (126.57–187.51) | 0.088 |

| Variables | Control Group Before Intervention | Control Group After Intervention | p | ||

| M ± SD | Me (IQR) | M ± SD | Me (IQR) | ||

| TAS (µmol/L) | 355.58 ± 35.48 | 357.74 (325.28–383.82) | 368.21 ± 34.49 | 365.92 (346.29–393.97) | 0.261 |

| TOS (µmol/L) | 246.26 ± 21.67 | 245.70 (236.46–261.74) | 240.49 ± 21.53 | 243.43 (227.82–254.60) | 0.404 |

| OSI | 0.699 ± 0.095 | 0.703 (0.633–0.748) | 0.658 ± 0.080 | 0.667 (0.613–0.724) | 0.403 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 4.309 ± 0.555 | 4.320 (3.945–4.765) | 4.446 ± 0.545 | 4.430 (4.140–4.915) | 0.434 |

| GPx (nmol/min/mL) | 173.28 ± 70.46 | 163.65 (118.16–237.77) | 185.92 ± 72.54 | 170.02 (134.49–253.28) | 0.579 |

| CAT (nmol/min/mL) | 135.68 ± 42.08 | 135.78 (99.53–174.79) | 140.16 ± 41.87 | 139.98 (101.87–177.49) | 0.738 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zujko-Kowalska, K.; Stefanek, M.; Łuszczewska, I.; Małek, Ł.; Kamiński, K.A.; Zujko, M.E. The Effect of Newly Designed High-Antioxidant Food Products on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Athletes. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121457

Zujko-Kowalska K, Stefanek M, Łuszczewska I, Małek Ł, Kamiński KA, Zujko ME. The Effect of Newly Designed High-Antioxidant Food Products on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Athletes. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121457

Chicago/Turabian StyleZujko-Kowalska, Kinga, Magdalena Stefanek, Izabela Łuszczewska, Łukasz Małek, Karol Adam Kamiński, and Małgorzata Elżbieta Zujko. 2025. "The Effect of Newly Designed High-Antioxidant Food Products on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Athletes" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121457

APA StyleZujko-Kowalska, K., Stefanek, M., Łuszczewska, I., Małek, Ł., Kamiński, K. A., & Zujko, M. E. (2025). The Effect of Newly Designed High-Antioxidant Food Products on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Markers in Athletes. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121457