Effects of Food Enrichment Based on Diverse Feeding Regimes on Growth, Immunity, and Stress Resistance of Nibea albiflora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Fish and Food Enrichment Construction

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Feeding Trial

2.3.2. Dehydration Stress Assay

2.4. Monitoring Indicators and Method

2.4.1. Growth Performance

2.4.2. Physiological and Biochemical Indexes

2.5. Histology Observation

2.6. Transcriptome Analysis

2.7. qRT-PCR Verification

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Physiological and Biochemical Indexes

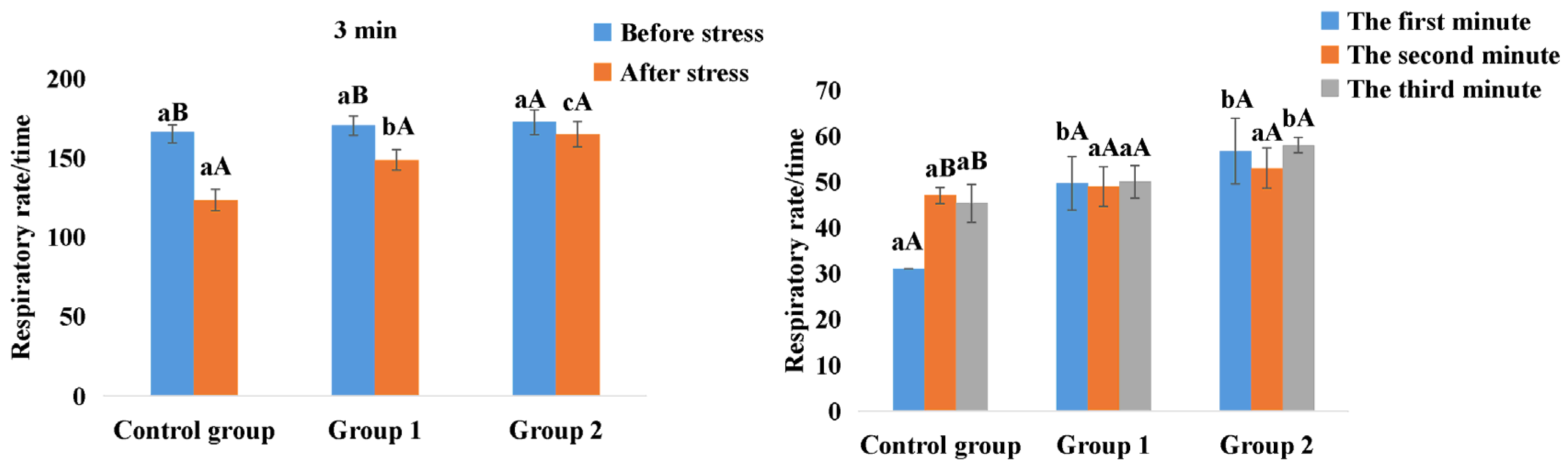

3.3. Respiratory Rate Statistics for the Dehydration Stress Assay

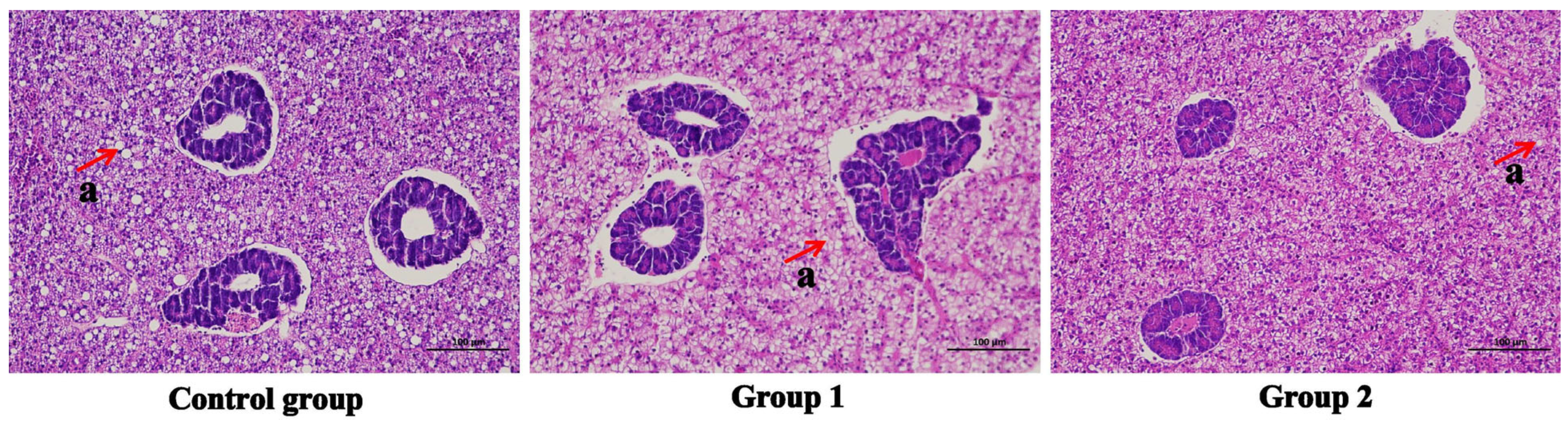

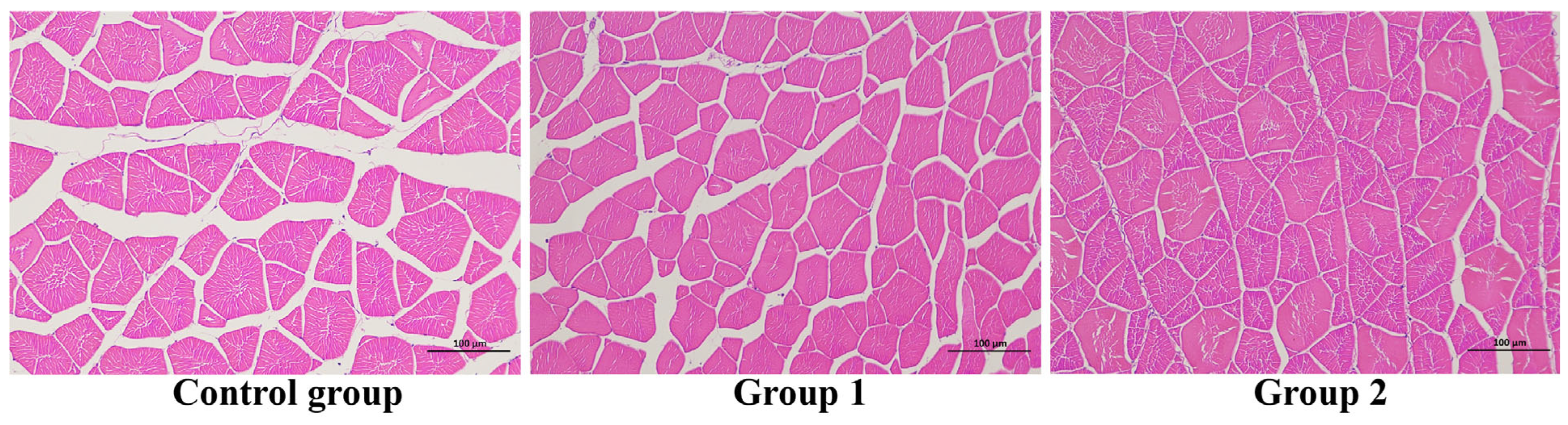

3.4. Histology Observation

3.5. Transcriptomic Analysis

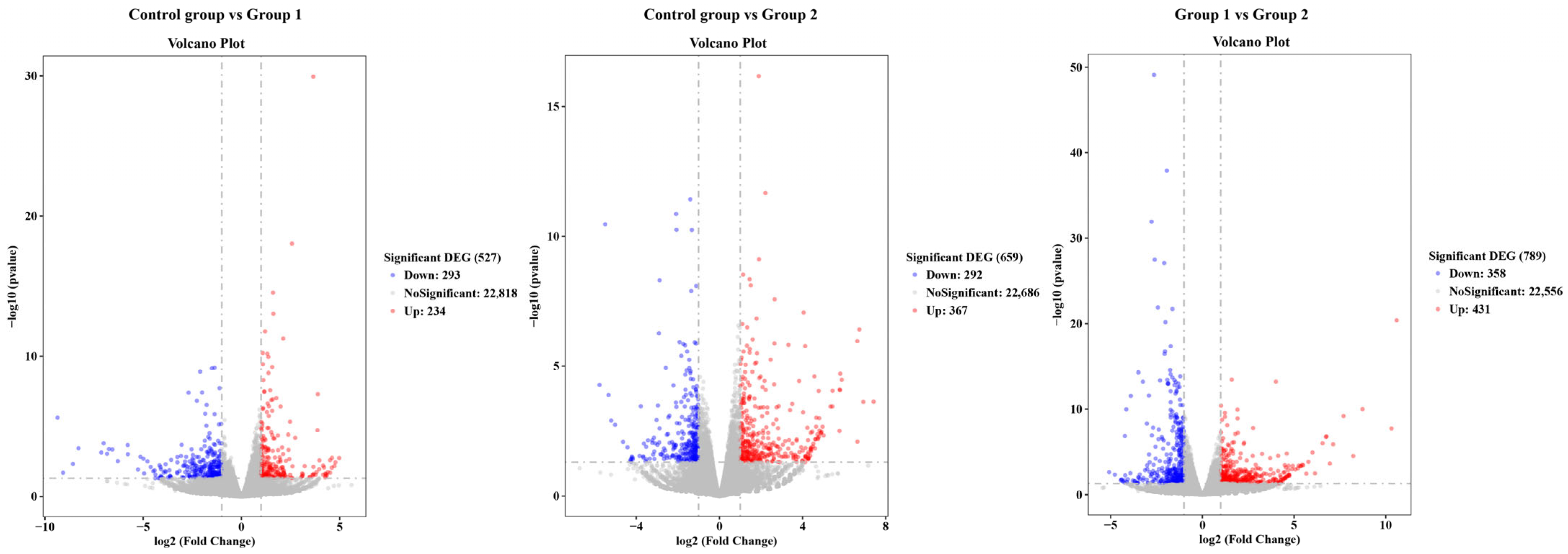

3.5.1. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.5.2. GO Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.5.3. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.5.4. Differentially Expressed Genes Verification by qRT-PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WG | Weight gain |

| SGR | Specific growth rate |

| K | Condition factor |

| PER | Protein efficiency ratio |

| HSI | Hepatosomatic index |

| SR | Survival rate |

| UPC | Unit production cost |

| TFC | total feed cost |

| TBG | total biomass gain |

References

- Heenan, A.; Simpson, S.D.; Meekan, M.G.; Healy, S.D.; Braithwaite, V.A. Restoring depleted coral-reef fish populations through recruitment enhancement: A proof of concept. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 75, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Sundh, H.; Buchmann, K.; Douxfils, J.; Sundell, K.S.; Mathieu, C.; Ruane, N.; Jutfelt, F.; Toften, H.; Vaughan, L. Health of farmed fish: Its relation to fish welfare and its utility as welfare indicator. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence-Jones, H.C.; Frommen, J.G.; Jones, N.A.R. Closing the Gaps in Fish Welfare: The Case for More Fundamental Work Into Physical Enrichment. Fish Fish. 2025, 26, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderzwalmen, M.; Carey, P.; Snellgrove, D.; Sloman, K.A. Benefits of enrichment on the behaviour of ornamental fishes during commercial transport. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewett, T.A.; Ackerly, K.L.; Sundin, J.; Clark, T.D.; Rowsey, L.E.; Griffin, R.A.; Metz, M.; Kuchenmüller, L.; Leeuwis, R.H.J.; Levet, M.; et al. Unintended Consequences of Aquatic Enrichment in Experimental Biology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8301–8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Lin, W.H.; Li, Y.Q.; Yuan, X.Y.; He, X.Q.; Zhao, H.C.; Mo, J.Z.; Lin, J.Q.; Yang, L.L.; Liang, B.; et al. Physical enrichment for improving welfare in fish aquaculture and fitness of stocking fish: A review of fundamentals, mechanisms and applications. Aquaculture 2023, 574, 739651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Alexander, M.E.; Lightbody, S.; Snellgrove, D.; Smith, P.; Bramhall, S.; Henriquez, F.L.; McLellan, I.; Sloman, K.A. Influence of social enrichment on transport stress in fish: A behavioural approach. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 262, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, A.; Stomp, M.; Rouby, M.; Ferreira, V.H.B.; Bégout, M.-L.; Benhaïm, D.; Labbé, L.; Tocqueville, A.; Levadoux, M.; Calandreau, L.; et al. Cognitive enrichment to increase fish welfare in aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A.M.; De la Llave-Propín, Á.; De la Fuente, J.; Pérez, C.; de Chavarri, E.G.; Díaz, M.T.; Cabezas, A.; González-Garoz, R.; Torrent, F.; Villarroel, M.; et al. Using underwater currents as an occupational enrichment method to improve the stress status in rainbow trout. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 50, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, A.; Roy, J.; Brunet, V.; Baranek, E.; Le-Calvez, J.M.; Kerneis, T.; Batard, A.; Calvez, S.; Pineau, L.; Milla, S.; et al. Feeding predictability as a cognitive enrichment protects brain function and physiological status in rainbow trout: A multidisciplinary approach to assess fish welfare. Animal 2024, 18, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherdson, D.J.; Carlstead, K.; Mellen, J.D.; Seidensticker, J. The influence of food presentation on the behavior of small cats in confined environments. Zoo Biol. 1993, 12, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelka, J. Problem-seeking behaviour in rats. Can. J. Psychol. 1956, 10, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.E.; Shapiro, H.G.; Ehmke, E.E. Behavioral responses of three lemur species to different food enrichment devices. Zoo Biol. 2018, 37, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavamian, Y.; Minier, D.E.; Jaffe, K.E. Effects of Complex Feeding Enrichment on the Behavior of Captive Malayan Sun Bears (Helarctos malayanus). J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 26, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashaw, M.J.; Gibson, M.D.; Schowe, D.M.; Kucher, A.S. Does enrichment improve reptile welfare? Leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) respond to five types of environmental enrichment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 184, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januszczak, I.S.; Bryant, Z.; Tapley, B.; Gill, I.; Harding, L.; Michaels, C.J. Is behavioural enrichment always a success? Comparing food presentation strategies in an insectivorous lizard (Plica plica). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 183, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, C.; Thompson, D.; Hao, C.; Houlahan, J. The response of amphibian larvae to exposure to a glyphosate-based herbicide (Roundup WeatherMax) and nutrient enrichment in an ecosystem experiment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 109, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Ashby, H.E.; Pankhurst, S.J. Effects of feeding enrichment on the behaviour and welfare of captive Waldrapps (Northern bald ibis) (Geronticus eremita). Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Lima, M.F.; de Azevedo, C.S.; Young, R.J.; Viau, P. Impacts of food-based enrichment on behaviour and physiology of male greater rheas (Rhea Americana, Rheidae, Aves). Papéis Avulsos Zool. 2019, 59, e20195911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz-Zukowska, R.; Puscion-Jakubik, A.; Grabia, M.; Perkowski, J.; Nowakowski, P.; Bielecka, J.; Soroczynska, J.; Kangowski, G.; Boltryk, J.M.; Socha, K. Nuts as a dietary enrichment with selected minerals-content assessment supported by chemometric analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.L.; Zheng, Y.T.; Zhang, X.M.; Xu, D.D.; Wang, J.X.; Sun, J.P. Effect of food enrichment based on diverse feeding regimes on the immunity of Nibea albiflora by biochemical and RNA-seq analysis of the spleen. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genom. Proteom. 2025, 53, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdue, B.M.; Beran, M.J.; Washburn, D.A. A computerized testing system for primates: Cognition, welfare, and the Rumbaughx. Behav. Process. 2018, 156, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, C.; Rajini, P.S. Glucose-rich diet aggravates monocrotophos-induced dopaminergic neuronal dysfunction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.W.; Czoty, P.W.; Porrino, L.J.; Nader, M.A. Social status in monkeys: Effects of social confrontation on brain function and cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 42, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, E.; Agh, N.; Malekzadeh Viayeh, R. Potential of plant oils as alternative to fish oil for live food enrichment: Effects on growth, survival, body compositions and resistance against environmental stresses in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2016, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl, L.M.; Donovan, D.A. Survival, growth, and radula morphology of Haliotis kamtschatkana postlarvae fed six species of benthic diatoms. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Tian, H.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Jiang, G.Z.; Liu, W.B. Feeding frequency affects stress, innate immunity and disease resistance of juvenile blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 38, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, K.N.; Rath, S.C.; Nayak, K.C.; Pradhan, C.; Mohanty, T.K.; Giri, S.S. Effect of restricted feeding and refeeding on compensatory growth, nutrient utilization and gain, production performance and whole body composition of carp cultured in earthen pond. Aquac. Nutr. 2017, 23, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwy, F.M.; Kohbara, J. Dualistic feeding pattern of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, L.)reared under different self-feeding system conditions. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.Y.; Lou, B.; Xu, D.D.; Zhan, W.; Takeuchi, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, F. Induction of meiotic gynogenesis in yellow drum (Nibea albiflora, Sciaenidae) using heterologous sperm and evidence for female homogametic sex determination. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Yuan, X.W.; Guo, J.; Ling, J.Z.; Yang, L.L.; Li, S.F. Diet composition and feeding ecology of Nibea albiflora in Xiangshan Bay, east China Sea. J. Fish. Sci. China 2013, 20, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.G.; Dong, X.J.; Zuo, R.T.; Mai, K.S.; Ai, Q.H. Response of juvenile Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus) to different dietary fatty acid profiles: Growth performance, tissue lipid accumulation, liver histology and flesh texture. Aquaculture 2016, 461, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Erwan, E.; Nagasawa, M.; Furuse, M.; Chowdhury, V.S. Changes in free amino acid concentrations in the blood, brain and muscle of heat-exposed chicks. Br. Poult. Sci. 2014, 55, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.D.; Lu, L.; Chen, R.Y.; Li, S.S.; Xu, D.D. Exploring sexual dimorphism in the intestinal microbiota of the yellow drum (Nibea albiflora, Sciaenidae). Front. Microbiol 2022, 12, 808285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.L.; Shang-Guan, J.B.; Li, Z.B.; Huang, Z.F.; Shi, S.J.; Ye, Y.L. Effects of dietary vitamin E on the growth performance, immunity and digestion of Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ by physiology, pathology and RNA-seq. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Andraca, V.H.; Ángeles Campos, S.C.; Castillo-Juárez, H.; Marin-Coria, E.J.; Quintana-Casares, J.C.; Domínguez-May, R.; Campos-Montes, G.R. Different stocking density effects on growth performance, muscle protein composition, and production cost of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) juveniles in on-growing stage in biofloc system. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2002, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, L.G.; Lou, B.; Zhan, W.; Chen, R.Y.; Luo, S.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, Z.L. Effects of dietary protein level on growth performance, body composition and digestive enzyme activities of juvenile Nibea albiflora. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 27, 3763–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.G.; Ma, B.H.; Chen, D.X.; Lou, B.; Zhan, W.; Chen, R.Y.; Tan, P.; Xu, D.D.; Liu, F.; Xie, Q.P. Effect of dietary level of vitamin E on growth performance, antioxidant ability, and resistance to Vibrio alginolyticus challenge in yellow drum Nibea albiflora. Aquaculture 2019, 507, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mims, S.D.; Knaub, R.S. Condition Factors and Length-Weight Relationships of Pond-Cultured Paddlefish Polyodon spathula with Reference to Other Morphogenetic Relationships. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2010, 24, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Mao, Y.Q.; Cai, F.S. Nutritional lipid liver disease of grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idullus (C. et V.). Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 1990, 8, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.; Burkow, I.C.; Jobling, M. Patterns of growth and lipid deposition in cod (Gadus morhua L.) fed natural prey and fish-based feeds. Aquaculture 1993, 110, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Tian, L.X.; He, J.G.; Cao, J.M.; Liang, G.Y. The influence of feeding rate on growth, feed efficiency and body composition of juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquac. Int. 2005, 14, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.P. Utilization of dietary carbohydrate by fish. Aquaculture 1994, 124, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Luo, Y.; Li, X.J.; Dong, Y.; Liao, Y.; Yao, W.; Jin, Z.B.; Wu, X.Y. Effects of Dietary Carbohydrate/Lipid Ratios on Growth, Feed Utilization, Hematology Parameters, and Intestinal Digestive Enzyme Activities of Juvenile Hybrid Grouper (Brown-Marbled Grouper Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Giant Grouper E. lanceolatus ♂). North Am. J. Aquac. 2018, 80, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvier-Péres, A.; Kestemont, P. Development of some digestive enzymes in Eurasian perch larvae Perca fluviatilis. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2001, 24, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S.; Contois, J.H.; Tucker, K.L.; Wilson, P.W.; Schaefer, E.J.; Lammi-Keefe, C.J. Plasma retinol and plasma and lipoprotein tocopherol and carotenoid concentrations in healthy elderly participants of the Framingham Heart Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.A. Nutritional Biochemistry of the Vitamins; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, C.; Cabas Rodriguez, L.; Mulder, W.J.; Engelen-Smit, N.; Spekking, W.; van den Broek, L.A.M.; Olivieri, G.; Sijtsma, L. Energy consumption and water-soluble protein release by cell wall disruption of Nannochloropsis gaditana. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, P.; Di Stefano, L.; Di Meo, S. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Liang, Y.M.; Ramalingam, R.; Tang, S.W.; Shen, W.; Ye, R.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Au, D.W.T.; Lam, Y.W. Proteomic characterization of the interactions between fish serum proteins and waterborne bacteria reveals the suppression of anti-oxidative defense as a serum-mediated antimicrobial mechanism. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 62, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nya, E.J.; Austin, B. Use of garlic, Allium sativum, to control Aeromonas hydrophila infection in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Wang, W.J.; Hou, S.Y.; Fu, W.X.; Cai, J.; Xia, L.Q.; Lu, Y.S. Comparison of protective efficacy between two DNA vaccines encoding DnaK and GroEL against fish nocardiosis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 95, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, I.; Arnott, S.A.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Andrew, J.; Huntingford, F.A. Indirect fitness consequences of mate choice in sticklebacks: Offspring of brighter males grow slowly but resist parasitic infections. Proc. R. Soc. Lond Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, A.M. Hypothalamic- and pituitary-derived growth and reproductive hormones and the control of energy balance in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 287, 113322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pane, J.; Joly, L.; Koubbi, P.; Giraldo, C.; Monchy, S.; Tavernier, E.; Marchal, P.; Loots, C. Ontogenetic shift in the energy allocation strategy and physiological condition of larval plaice (Pleuronectes platessa). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrial, C.; Grassin-Delyle, S.; Salvator, H.; Brollo, M.; Naline, E.; Devillier, P. 15-Lipoxygenases regulate the production of chemokines in human lung macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 4319–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatzy, Y.; Palmer, M.A.; Brüne, B. Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B: Regulation, function, and its role in pathophysiology. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwindinger, W.F.; Betz, K.S.; Giger, K.E.; Sabol, A.; Bronson, S.K.; Robishaw, J.D. Loss of G Protein γ7 Alters Behavior and Reduces Striatal αolf Level and cAMP Production. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 6575–6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Szaumkessel, M.; Salaverria, I.; Simon, R.; Sauter, G.; Kiwerska, K.; Gawecki, W.; Bodnar, M.; Marszalek, A.; Richter, J.; et al. Loss of protein expression and recurrent DNA hypermethylation of the GNG7 gene in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Appl. Genet. 2012, 53, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, P.L.R.; Lima, D.; Mattos, J.J.; Bainy, A.C.D.; Grott, S.C.; Alves, T.C.; de Almeida, E.A.; da Silva, D.G.H. Fipronil impairs the GABAergic brain responses of Nile Tilapia during the transition from normoxia to acute hypoxia. J. Exp. Zool. Part A: Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2022, 339, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocker, C.N.; Yue, J.; Kim, D.; Qu, A.; Bonzo, J.A.; Gonzalez, F.J. Hepatocyte-specific PPARA expression exclusively promotes agonist-induced cell proliferation without influence from nonparenchymal cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 312, G283–G299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.C.; Wu, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.H.; Li, D.D.; Luo, Z. Magnesium Reduces Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in Yellow Catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) and Modulates Lipogenesis and Lipolysis via PPARA, JAK-STAT, and AMPK Pathways in Hepatocytes. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.X.; Ning, Z.W.; Huang, T.; Wen, B.; Liao, C.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, H.T.; Bian, Z.X. Cyclocarya paliurus Leaves Tea Improves Dyslipidemia in Diabetic Mice: A Lipidomics-Based Network Pharmacology Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.Q.; Lan, M.Y.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, Y.Q. Effects of florfenicol on the antioxidant and immune systems of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 140, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liang, Y.X.; Chen, Q.H.; Shan, S.J.; Yang, G.W.; Li, H. The function of NLRP3 in anti-infection immunity and inflammasome assembly of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 145, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Tang, L.S.; Feng, H. Mx1 of black carp functions importantly in the antiviral innate immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 58, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Gao, T.X.; Han, Z.Q. RNA-seq and Analysis of Argyrosomus japonicus Under Different Salinities. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 790065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.M.; Wang, L.; Ou, R.K.; Nie, X.P.; Yang, Y.F.; Wang, F.; Li, K.B. Effects of norfloxacin on hepatic genes expression of P450 isoforms (CYP1A and CYP3A), GST and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in Swordtail fish (Xiphophorus Helleri). Ecotoxicology 2015, 24, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.L.; Han, F.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.Q.; Bian, L.; Gao, T.X. Transcriptomic profiling reveals the immune response mechanism of the Thamnaconus modestus induced by the poly (I:C) and LPS. Gene 2024, 897, 148065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, J.N.; Shen, Q.; Chen, Z.L.; Qiao, Z.K. Investigating the mechanism of Tongqiao Huoxue decotion in the treatment of allergic rhinitis based on network pharmacology and molecular docking: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e33190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Singh, R.D.; Tiwari, R.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Roy, S.K.; Singh, D.; Srivastava, V. Mercury exposure induces cytoskeleton disruption and loss of renal function through epigenetic modulation of MMP9 expression. Toxicology 2017, 386, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, C.Z.; Yang, Q.H.; Dong, X.H.; Chi, S.Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Shi, L.L.; Tan, B.P. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of Wnt4, Wnt5, Wnt6, Wnt7, Wnt10 and Wnt16 from Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 54, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M.; Friedl, A.; Srivastava, M.; Soliman, H.; Secombes, C.J.; El-Matbouli, M. STAT3/SOCS3 axis contributes to the outcome of salmonid whirling disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wu, L.Q.; Lin, P.; Zhai, S.W.; Guo, S.L.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Wan, Q.J. First expression and immunogenicity study of a novel trivalent outer membrane protein (OmpII-U-A) from Aeromonas hydrophila, Vibrio vulnificus and Edwardsiella anguillarum. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.Z.; Liu, J.H.; Huang, D.; Guo, Y.L.; Luo, K.; Yang, M.X.; Gao, W.H.; Xu, Q.Q.; Zhang, W.B.; Mai, K.S. FoxO3 Modulates LPS-Activated Hepatic Inflammation in Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.J.; Fu, X.Z.; Liu, L.H.; Lin, Q.; Liang, H.R.; Huang, Z.B.; Li, N.Q. Molecular characterization and function of EGFR during viral infectionprocess in Mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 102, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciarelli, R.; Tasinato, A.; ClÉMent, S.; ÖZer, N.K.; Boscoboinik, D.; Azzi, A. α-Tocopherol specifically inactivates cellular protein kinase C α by changing its phosphorylation state. Biochem. J. 1998, 334, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | W0 (g) | WG (%) | SGR (%/day) | HSI (%) | K (g/cm3) | PER (%) | SR (%) | UPC RMB/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 29.72 ± 0.07 | 82.30 ± 14.03 a | 1.00 ± 0.13 a | 1.44 ± 0.02 b | 1.23 ± 0.06 a | 1.50 ± 0.23 a | 86.25 ± 4.78 a | 20.63 ± 2.75 |

| Group 1 | 29.65 ± 0.11 | 103.73 ± 10.50 b | 1.18 ± 0.09 b | 1.15 ± 0.06 a | 1.26 ± 0.01 a | 1.86 ± 0.09 b | 95.00 ± 0.00 b | 20.96 ± 0.99 |

| Group 2 | 29.57 ± 0.21 | 113.51 ± 11.33 b | 1.26 ± 0.09 b | 1.14 ± 0.04 a | 1.38 ± 0.03 b | 2.33 ± 0.11 c | 98.75 ± 2.50 b | 23.24 ± 1.16 |

| p-value 1 | 0.204 | 0.530 | 0.363 | 0.169 | 0.176 | 0.203 | 0.013 | 0.159 |

| p-value 2 | 0.013 | 0.502 | 0.361 | 0.025 | 0.796 | 0.331 | 0.072 | 0.203 |

| p-value | 0.397 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.141 |

| Groups | AMS(U/mgprot) | LPS (U/gprot) | Trypsin (U/mgprot) | AKP (U/100 mL) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Foregut | Stomach | Liver | Foregut | Stomach | Liver | Foregut | Stomach | Liver | Foregut | Stomach | |

| Control | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 2.95 ± 0.49 | 0.27 ± 0.12 | 2.47 ± 0.15 a | 2.35 ± 0.39 a | 2.40 ± 0.18 a | 3.48 ± 0.62 a | 87.70 ± 9.85 a | 21.95 ± 4.34 a | 50.82 ± 7.42 a | 3122.86 ± 294.30 | 181.42 ± 4.82 a |

| Group 1 | 1.11 ± 0.12 | 2.43 ± 0.21 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 3.41 ± 0.13 b | 3.79 ± 0.76 b | 2.64 ± 0.30 a | 5.15 ± 0.23 b | 127.79 ± 11.22 b | 25.26 ± 2.65 ab | 76.12 ± 2.93 b | 3166.05 ± 138.31 | 173.09 ± 6.47 a |

| Group 2 | 1.18 ± 0.07 | 2.58 ± 0.15 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 3.69 ± 0.27 b | 3.63 ± 0.25 b | 3.05 ± 0.16 b | 6.49 ± 0.92 c | 117.01 ± 10.29 b | 30.07 ± 1.15 b | 95.73 ± 7.94 c | 3036.57 ± 134.27 | 218.25 ± 12.28 b |

| p-value 1 | 0.307 | 0.183 | 0.075 | 0.392 | 0.209 | 0.259 | 0.317 | 0.963 | 0.335 | 0.281 | 0.132 | 0.254 |

| p-value 2 | 0.425 | 0.273 | 0.706 | 0.207 | 0.864 | 0.337 | 0.968 | 0.542 | 0.743 | 0.837 | 0.275 | 0.12 |

| p-value 3 | 0.603 | 0.207 | 0.306 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.740 | 0.001 |

| Groups | Serum | Liver | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG (mmol/L) | HDL-C (mmol/L) | T-CHO (mmol/L) | TG (mmol/gprot) | HDL-C (mmol/gprot) | T-CHO (mmol/gprot) | |

| Control | 1.20 ± 0.20 b | 2.19 ± 0.13 a | 2.21 ± 0.13 a | 1.51 ± 0.16 b | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.02 a |

| Group 1 | 1.30 ± 0.19 b | 2.23 ± 0.17 a | 2.57 ± 0.21 b | 1.01 ± 0.09 a | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.02 b |

| Group 2 | 0.82 ± 0.04 a | 2.59 ± 0.16 b | 2.88 ± 0.10 c | 1.18 ± 0.11 a | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.04 c |

| p-value 1 | 0.208 | 0.784 | 0.323 | 0.425 | 0.96 | 0.352 |

| p-value 2 | 0.62 | 0.643 | 0.552 | 0.383 | 0.294 | 0.518 |

| p-value 3 | 0.023 | 0.036 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.992 | 0.001 |

| Groups | T-AOC (mM) | SOD (U/mL) | CAT (U/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | |

| Control | 0.37 ± 0.03 aA | 0.46 ± 0.04 B | 8.45 ± 0.96 bB | 5.84 ± 0.26 A | 8.69 ± 0.49 ab | 8.22 ± 0.59 |

| Group 1 | 0.68 ± 0.06 bB | 0.51 ± 0.03 A | 5.93 ± 0.43 a | 5.03 ± 0.38 | 7.84 ± 0.16 aA | 8.87 ± 0.34 B |

| Group 2 | 0.71 ± 0.06 bB | 0.48 ± 0.01 A | 9.29 ± 0.76 bB | 5.73 ± 0.38 A | 9.58 ± 0.62 b | 8.73 ± 0.40 |

| p-value 1 | 0.432 | 0.351 | 0.49 | 0.604 | 0.167 | 0.377 |

| p-value 2 | 0.061 | 0.902 | 0.369 | 0.414 | 0.437 | 0.396 |

| p-value 3 | 0.000 | 0.178 | 0.004 | 0.057 | 0.011 | 0.266 |

| Groups | T-AOC (mmol/gprot) | SOD (U/mgprot) | CAT (U/mgprot) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | |

| Control | 0.10 ± 0.01 aA | 0.12 ± 0.01 bB | 20.00 ± 5.52 a | 15.73 ± 4.22 a | 8.352 ± 2.04 aB | 3.38 ± 0.85 aA |

| Group 1 | 0.12 ± 0.01 bA | 0.17 ± 0.01 cB | 20.18 ± 3.39 aA | 36.35 ± 3.13 cB | 15.35 ± 1.84 bB | 10.35 ± 0.80 bA |

| Group 2 | 0.13 ± 0.01 bB | 0.10 ± 0.01 aA | 30.37 ± 3.01 b | 25.46 ± 1.15 b | 23.27 ± 2.99 cB | 14.77 ± 2.15 cA |

| p-value 1 | 0.436 | 0.258 | 0.294 | 0.101 | 0.645 | 0.08 |

| p-value 2 | 0.765 | 0.254 | 0.347 | 0.742 | 0.926 | 0.311 |

| p-value 3 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Groups | TP (gprot/L) | AKP (U/100 mL) | ACP (U/100 mL) | LZM (U/mL) | C3 (µg/mL) | IgM (µg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | |

| Control | 21.02 ± 0.65 aB | 11.20 ± 0.27 aA | 1.69 ± 0.21 aA | 2.12 ± 0.15 B | 5.45 ± 0.19 aB | 3.82 ± 0.08 aA | 34.01 ± 2.17 b | 30.00 ± 1.88 a | 1088.20 ± 22.39 bB | 804.13 ± 69.27 bA | 139.91 ± 12.37 b | 111.74 ± 13.54 b |

| Group 1 | 24.40 ± 1.23 bB | 13.09 ± 1.14 bA | 2.13 ± 0.05 b | 2.05 ± 0.11 | 5.06 ± 0.36 a | 4.85 ± 0.22 c | 34.27 ± 2.39 bB | 26.46 ± 3.08 aA | 881.07 ± 40.90 aB | 525.26 ± 88.63 aA | 120.80 ± 13.27 abB | 76.80 ± 2.59 aA |

| Group 2 | 29.64 ± 1.63 cB | 14.69 ± 0.64 cA | 2.42 ± 0.24 bB | 1.90 ± 0.08 A | 6.81 ± 0.25 bB | 4.29 ± 0.18 bA | 28.32 ± 1.23 aA | 35.21 ± 2.01 bB | 1068.10 ± 46.18 bB | 780.13 ± 133.49 bA | 109.42 ± 8.46 a | 102.74 ± 2.88 b |

| p-value 1 | 0.317 | 0.196 | 0.106 | 0.332 | 0.481 | 0.250 | 0.427 | 0.405 | 0.386 | 0.545 | 0.579 | 0.043 |

| p-value 2 | 0.559 | 0.343 | 0.809 | 0.912 | 0.263 | 0.577 | 0.804 | 0.871 | 0.053 | 0.626 | 0.053 | 0.319 |

| p-value 3 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.128 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.047 | 0.005 |

| Groups | AKP (U/100 mL) | ACP (U/100 mL) | LZM (U/mgprot) | C3 (mg/gprot) | IGM (mg/gprot) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | Feeding Trial | Air Exposure Stress | |

| Control | 50.82 ± 7.42 a | 39.88 ± 8.40 a | 224.02 ± 39.98 a | 193.13 ± 45.25 a | 9.84 ± 3.38 aB | 3.11 ± 0.60 A | 193.55 ± 18.39 B | 134.39 ± 11.21 aA | 31.08 ± 3.24 B | 21.15 ± 1.96 bA |

| Group 1 | 76.12 ± 2.93 b | 66.69 ± 8.04 b | 310.98 ± 12.97 b | 330.01 ± 63.49 b | 19.92 ± 3.47 bB | 4.45 ± 0.84 A | 194.21 ± 2.20 | 184.04 ± 28.05 b | 24.87 ± 3.12 | 20.83 ± 3.32 b |

| Group 2 | 95.73 ± 7.94 cB | 38.46 ± 5.93 aA | 313.64 ± 51.44 b | 221.88 ± 42.75 a | 17.03 ± 2.29 bB | 3.38 ± 0.49 A | 198.01 ± 27.41 B | 116.54 ± 9.60 aA | 30.09 ± 4.84 B | 15.45 ± 1.68 aA |

| p-value 1 | 0.281 | 0.777 | 0.249 | 0.621 | 0.813 | 0.469 | 0.055 | 0.225 | 0.447 | 0.337 |

| p-value 2 | 0.837 | 0.267 | 0.688 | 0.575 | 0.955 | 0.505 | 0.285 | 0.205 | 0.384 | 0.949 |

| p-value 3 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.018 | 0.099 | 0.954 | 0.010 | 0.182 | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruan, Y.; Sun, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Gao, T.; Xu, A.; Zhang, X. Effects of Food Enrichment Based on Diverse Feeding Regimes on Growth, Immunity, and Stress Resistance of Nibea albiflora. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121446

Ruan Y, Sun J, Zheng Y, Wang J, Xu D, Gao T, Xu A, Zhang X. Effects of Food Enrichment Based on Diverse Feeding Regimes on Growth, Immunity, and Stress Resistance of Nibea albiflora. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121446

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Yuhan, Jipeng Sun, Yuting Zheng, Jiaxing Wang, Dongdong Xu, Tianxiang Gao, Anle Xu, and Xiumei Zhang. 2025. "Effects of Food Enrichment Based on Diverse Feeding Regimes on Growth, Immunity, and Stress Resistance of Nibea albiflora" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121446

APA StyleRuan, Y., Sun, J., Zheng, Y., Wang, J., Xu, D., Gao, T., Xu, A., & Zhang, X. (2025). Effects of Food Enrichment Based on Diverse Feeding Regimes on Growth, Immunity, and Stress Resistance of Nibea albiflora. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121446