Iron Chelation Reduces Intracellular Hydroxyl Radicals in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Independently of Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Evaluation of Senescent Cells

2.4. Measurement of Catalase Activity

2.5. Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide Production

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.8. Fluorescent Staining (Superoxide, Fe2+, HPF, and Mitochondria)

2.9. Image Measurement and Image Adjustment

2.10. Cellular Exposure to DFO and Iron or Hydrogen Peroxide

2.11. Hydroxyl Radical Induction by Hydrogen Peroxide

2.12. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. The Number of Senescent NHDFs Positive for SA-β-Galactosidase Increased with Increasing Time in Culture

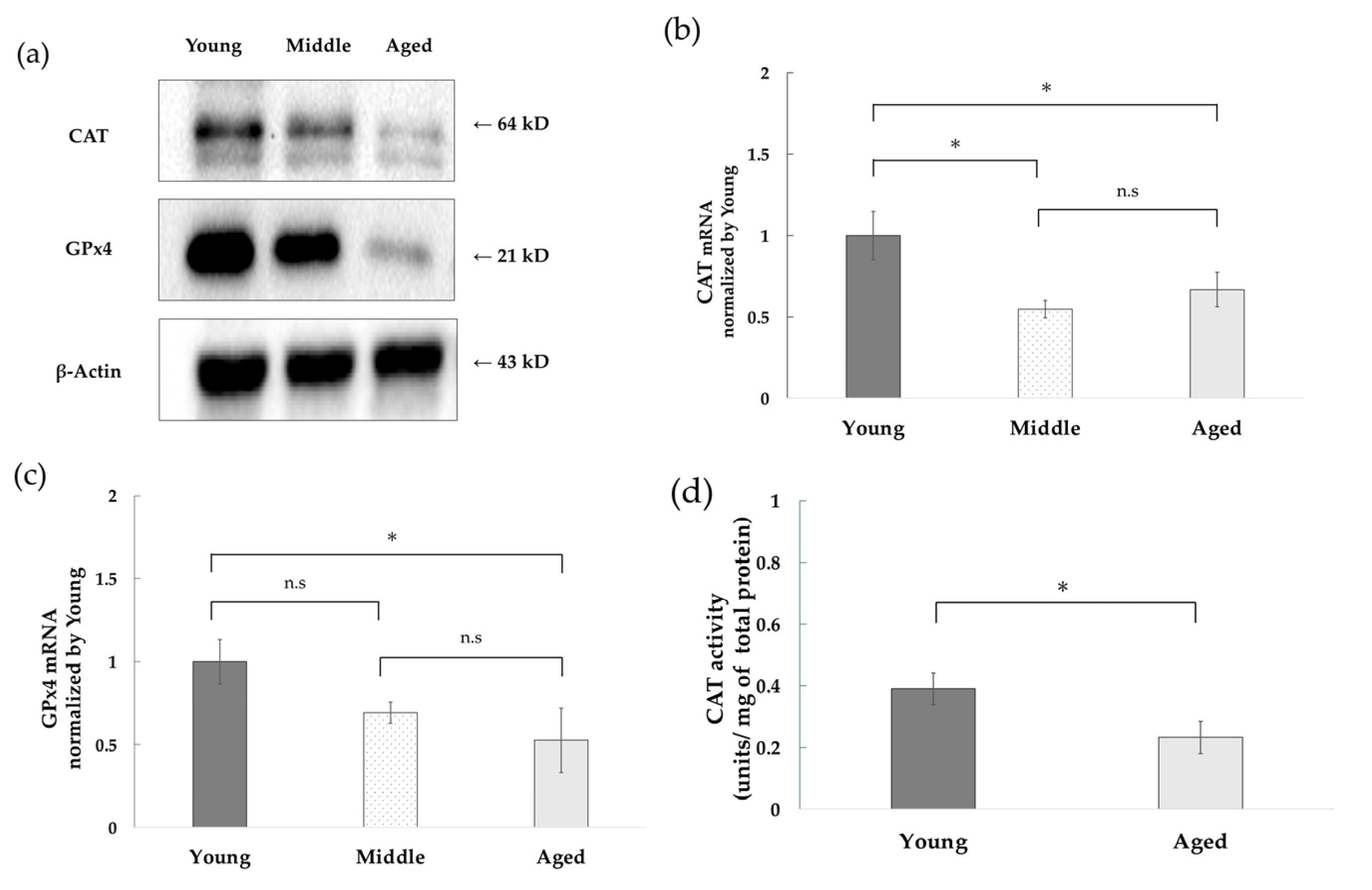

3.2. Decreased Expression of CAT and GPx4 and Decreased CAT Activity with Replicative Aging of NHDFs

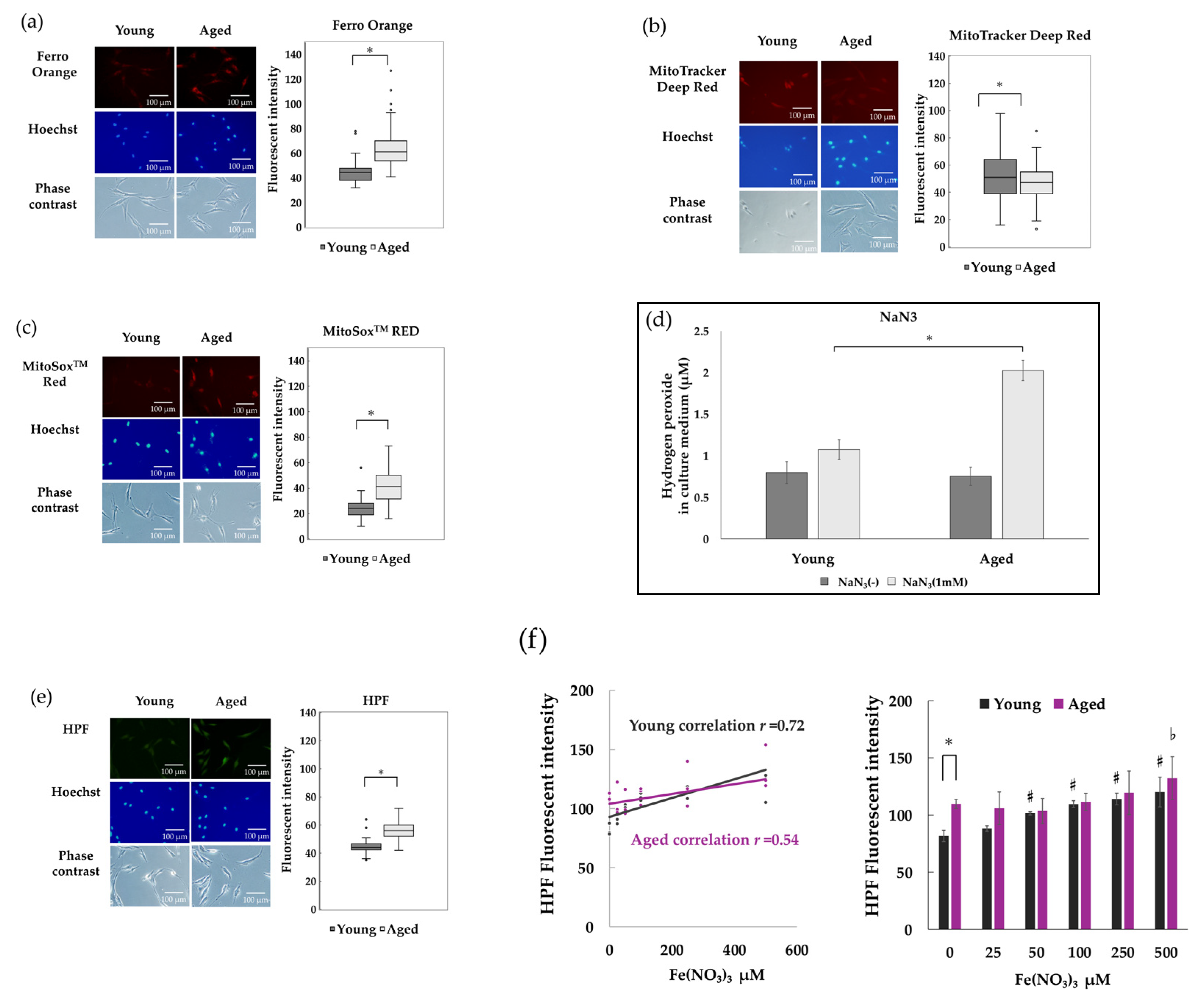

3.3. Intracellular Free Fe2+ Accumulates and ROS Increases in Senescent NHDFs

3.4. Hydroxyl Radicals in NHDFs Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide and Fe2+ Were Attenuated by Iron Chelators

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHP | 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| CAT | Catalase |

| DFO | Deforoxamine–mesylate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| E-MEM | Eagle’s minimal essential medium |

| Fe(NO3)3 | Iron (II) nitrate hexahydrate |

| GPx4 | Glutathione Peroxidase 4 |

| HBSS | Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution |

| HPF | Hydroxyphenyl Fluorescein |

| NaN3 | Sodium azide |

| NHDFs | Normal human dermal fibroblasts |

| Nrf2-ARE | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2—Antioxidant Response Element |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PVDF | Poly Vinylidene Di-Fluoride |

| RIPA | Radio-immune precipitation assay |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RT-PCR | Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| 3-AT | 3-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole |

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

References

- Beckman, K.B.; Ames, B.N. The Free Radical Theory of Aging Matures. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78, 547–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Beccaria, M.; Martínez, P.; Flores, J.M.; Blasco, M.A. In vivo role of checkpoint kinase 2 in signaling telomere dysfunction. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, N.; Vierkoetter, A.; Kraemaer, U.; Suguri, D.; Matui, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Kurtomann, J.; Morita, A. Mitochondrial common deletion mutation and extrinsic skin ageing in German and Japanese women. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 21, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutmann, J.; Schroeder, P. Role of Mitochondria in Photoaging of Human Skin: The Defective Powerhouse Model. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2009, 14, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.H.; Lee, H.C.; Wei, Y.-H. Photoageing-associated mitochondrial DNA length mutations in human skin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1995, 287, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Hammerberg, C.; Li, Y.; He, T.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Expression of catalytically active matrix metalloproteinase-1 in dermal fibroblasts induces collagen fragmentation and functional alterations that resemble aged human skin. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killilea, D.W.; Wong, S.L.; Cahaya, H.S.; Atamna, H.; Ames, B.N. Iron Accumulation during Cellular Senescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1019, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Kornatowski, M.; Krzywińska, O.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Changes in the blood antioxidant defense of advanced age people. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodier, F.; Coppé, J.P.; Patil, C.K.; Hoeijmakers, W.A.M.; Muñoz, D.P.; Raza, S.R.; Freund, A.; Campeau, E.; Davalos, A.R.; Campisi, J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killilea, D.W.; Atamna, H.; Liao, C.; Ames, B.N. Iron Accumulation During Cellular Senescence in Human Fibroblasts In Vitro. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2003, 5, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enami, S.; Sakamoto, Y.; Colussi, A.J. Fenton chemistry at aqueous interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, V.; Henríquez, A.; Freer, J.; Contreras, D. Reactivity of catecholamine-driven Fenton reaction and its relationships with iron (III) speciation. Redox Rep. 2015, 20, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcello, E.; Herpain, A.; Tomatis, M.; Turci, F.; Jacques, P.J.; Lison, D. Hydroxyl radicals and oxidative stress: The dark side of Fe corrosion. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 185, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yi, J.; Zhu, J.; Minikes, A.M.; Monian, P.; Thompson, C.B.; Jiang, X. Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2018, 73, 354–363.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, K.; Ozaki, A.; Yagi, M.; Ando, H. Measurement of Catalase Activity Using Catalase Inhibitors. J. Anal. Sci. Methods Instrum. 2024, 14, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, T.; Ohara, T.; Noma, K.; Katsura, Y.; Katsube, R.; Kashima, H.; Kato, T.; Tomono, Y.; Tazawa, H.; Kagawa, S.; et al. Iron depletion is a novel therapeutic strategy to target cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 98405–98416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Lee, H.C.; Fahn, H.J.; Wei, Y.H. Oxidative damage elicited by imbalance of free radical scavenging enzymes is associated with large-scale mtDNA deletions in aging human skin. Mutat. Res. 1999, 423, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, J.F.; Maines, M.D. Regulation and expression of heme oxygenase enzymes in aged-rat brain: Age related depression in HO-1 and HO-2 expression and altered stress-response. J. Neural Transm. 2006, 113, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Bailey-Downs, L.; Gautam, T.; Sosnowska, D.; Wang, M.; Monticone, R.E.; Telljohann, R.; Pinto, J.T.; de Cabo, R.; Sonntag, W.E.; et al. Age-associated vascular oxidative stress, Nrf2 dysfunction, and NF-{kappa}B activation in the nonhuman primate Macaca mulatta. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011, 66, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Davies, K.J.; Forman, H.J. Oxidative stress response and Nrf2 signaling in ageng. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyokuni, S.; Yanatori, I.; Kong, Y.; Zheng, H.; Motooka, Y.; Jiang, L. Ferroptosis at the Crossroads of Infection, Aging and Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2665–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maus, M.; Lopez-Polo, V.; Mateo, L.; Lafarga, M.; Aguilera, M.; De Lama, E.; Meyer, K.; Sola, A.; Lopez-Martinez, C.; Lopez-Alonso, I.; et al. Iron accumulation drives fibrosis, senescence and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 2111–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, J.; Robert, L. Cell Senescence: Role in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. In Aging: Facts and Theories; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 39, pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, J.M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014, 509, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masaldan, S.; Clatworthy, S.-A.S.; Gamell, C.; Meggyesy, P.M.; Rigopoulos, A.-T.; Haupt, S.; Ygal Haupt, Y.; Denoyer, D.; Adlard, P.A.; Bush, A.-I.; et al. Iron accumulation in senescent cells is coupled with impaired ferritinophagy and inhibition of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, H.; Atsumi, T.; Sakurai, H. Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide and Hydroxyl Radicals in Murine Skin Fibroblasts under UVB Irradiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 206, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, A.; Jung, T.; Grimm, S.; Grune, T. Lipofuscin-bound iron is a major intracellular source of oxidants: Role in senescent cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, A.; Weiss, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Modulation of Cellular Iron Metabolism by Hydrogen Peroxide: Effect of H2O2 on the expression and function of iron-responsive element-containig mRNAs in B6 fibroblast. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19738–19745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinnerthaler, M.; Bischof, J.; Streubel, M.K.; Trost, A.; Richte, K. Oxidative Stress in Aging Human Skin. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 545–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Iketani, M.; Ito, M.; Ohsawa, I. Temporal changes in mitochondrial function and reactive oxygen species generation during the development of replicative senescence in human fibroblasts. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 165, 111866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamna, H.; Killilea, D.W.; Killilea, A.N.; Ames, B.N. Heme deficiency may be a factor in the mitochondrial neuronal decay of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14807–14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamna, H. Heme, iron, and the mitochondrial decay of ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2004, 3, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftel, A.D.; Wilbrecht, C.; Stehling, O.; Niggemeyer, B.; Elsässer, H.P.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Lill, R. The human mitochondrial ISCA1, ISCA2, and IBA57 proteins are required for [4Fe-4S] protein maturation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Fukushima, K.; Nishizaki, K. The discovery of acatalasemia (lack of catalase in the blood) and its significance in human genetics. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2024, 100, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, G.; Taddeo, M.A.; Petersen, R.B.; Castellani, R.J.; Harris, P.L.R.; Siedlak, S.L.; Cash, A.D.; Liu, Q.; Nunomura, A.; Atwood, C.S.; et al. Adventiously-bound redox active iron and copper are at the center of oxidative damage in Alzheimer disease. Biometals 2003, 16, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, E.C.; Brandel, J.P.; Galle, P.; Javoy-Agid, F.; Agid, Y. Iron and aluminum increase in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson’s disease: An X-ray microanalysis. J. Neurochem. 1991, 56, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yantiri, F.; Andersen, J.K. The Role of Iron in Parkinson Disease and 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine Toxicity. IUBMB Life 1999, 48, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Chilakala, A.; Ananth, S.; Mandala, A.; Veeranan-Karmegam, R.; Powell, F.L.; Ganapathy, V.; Gnana-Prakasam, J.P. Renal iron accelerates the progression of diabetic nephropathy in the HFE gene knockout mouse model of iron overload. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 317, F512–F517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Jiang, C.; Peng, S.; Yao, P.; Tang, Y. Excess iron accumulation mediated senescence in diabetic kidney injury. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghugre, N.R.; Ramanan, V.; Pop, M.; Yang, Y.; Barry, J.; Qiang, B.; Connelly, K.A.; Dick, A.J.; Wright, G.A. Quantitative Tracking of Edema, Hemorrhage, and Microvascular Obstruction in Subacute Myocardial Infarction in a Porcine Model by MRI: Quantitative Tracking of Edema, Hemorrhage, and MVO. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011, 66, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Jin, S.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Dai, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, L.F. Altered expression of ferroptosis markers and iron metabolism reveals a potential role of ferroptosis in vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2022, 35, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Palte, M.J.; Deik, A.A.; Li, H.; Eaton, J.K.; Wang, W.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Deasy, R.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Dančík, V.; et al. A GPX4-dependent cancer cell state underlies the clear-cell morphology and confers sensitivity to ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Zhu, G.; Yin, Y.; Diao, H.; Liu, Z.; Sun, S.; Guo, Z.; Xu, W.; Xu, J.; Cui, C.; et al. Dual-Responsive multifunctional “core-shell” magnetic nanoparticles promoting Fenton reaction for tumor ferroptosis therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 622, 121898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajah, J.R.; Chang, J.; Goettel, J.A.; Alan SVerkman, A.S.; Lencer, W.I. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide-dependent responses to environmental stress in colonic epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinotti, S.; Laforenza, U.; Patrone, M.; Moccia, F.; Ranzato, E. Honey-Mediated Wound Healing: H2O2 Entry through AQP3 Determines Extracellular Ca2+ Influx. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu-Hsiang Liu, S.-H.; Lin, W.-C.; Liao, E.-C.; Lin, Y.-F.; Wang, C.-S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Pei, D.; Hsu, C.-H. Aquaporin-8 promotes human dermal fibroblasts to counteract hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage: A novel target for management of skin aging. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20220828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Culture Duration (Days) |

|---|---|

| Young | 68 ± 15 |

| Aged | 141 ± 28 |

| Middle | Approximately 100 days |

| Primar Name | Sequence | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|

| CAT F | GACTGACCAGGGCATCAAAAACC | NM_001752.4 |

| CAT R | TGCCTGATTAAATGTCATGACCTGG | NM_001752.4 |

| Gpx4 F | CGATACGCTGAGTGTGGTTT | NM_001367832.1 |

| Gpx4 R | CGGCGAACTCTTTGATCTCTT | NM_001367832.1 |

| β-actin F | AGAAAATCTGGCACCACACC | NM_001101.5 |

| β-actin F | AGAGGCGTACAGGGATAGCA | NM_001101.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takemoto, K.; Ozaki, A.; Tanii, Y.; Yagi, M.; Ichihashi, M.; Ando, H. Iron Chelation Reduces Intracellular Hydroxyl Radicals in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Independently of Aging. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121437

Takemoto K, Ozaki A, Tanii Y, Yagi M, Ichihashi M, Ando H. Iron Chelation Reduces Intracellular Hydroxyl Radicals in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Independently of Aging. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121437

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakemoto, Kazunori, Ami Ozaki, Yusuke Tanii, Masayuki Yagi, Masamitsu Ichihashi, and Hideya Ando. 2025. "Iron Chelation Reduces Intracellular Hydroxyl Radicals in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Independently of Aging" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121437

APA StyleTakemoto, K., Ozaki, A., Tanii, Y., Yagi, M., Ichihashi, M., & Ando, H. (2025). Iron Chelation Reduces Intracellular Hydroxyl Radicals in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Independently of Aging. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121437