Dysregulated Redox Signaling and Its Impact on Inflammatory Pathways, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Autophagy and Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms of Intracellular ROS Generation

3. Cellular Antioxidant System

4. Physiological Role of ROS, Redox Signaling and Redox Homeostasis

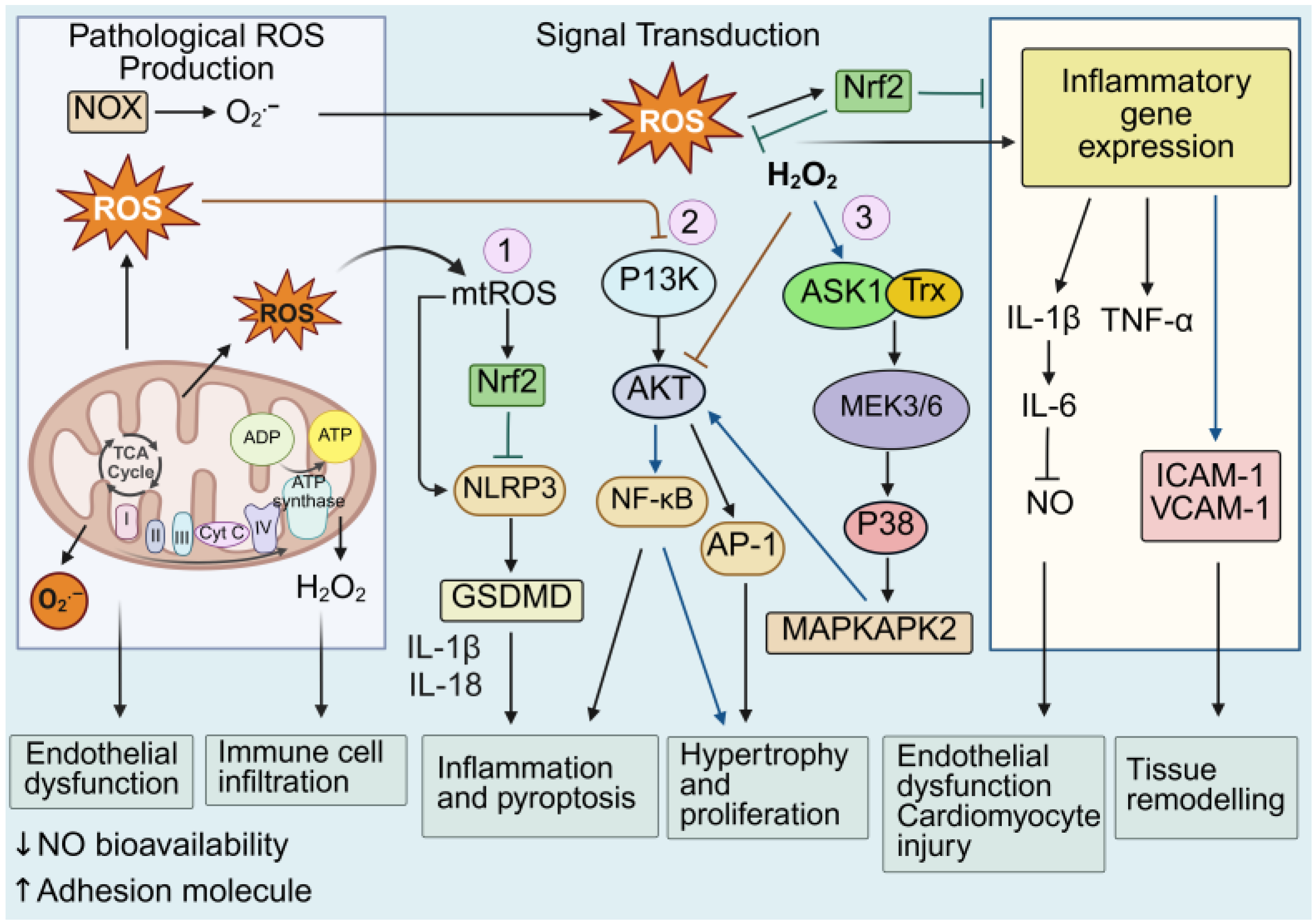

5. Dysregulated Redox Regulation: A Molecular Link to Inflammatory Pathways and Cell Death

6. The Crosstalk Between Redox Signaling and Mitochondrial Function

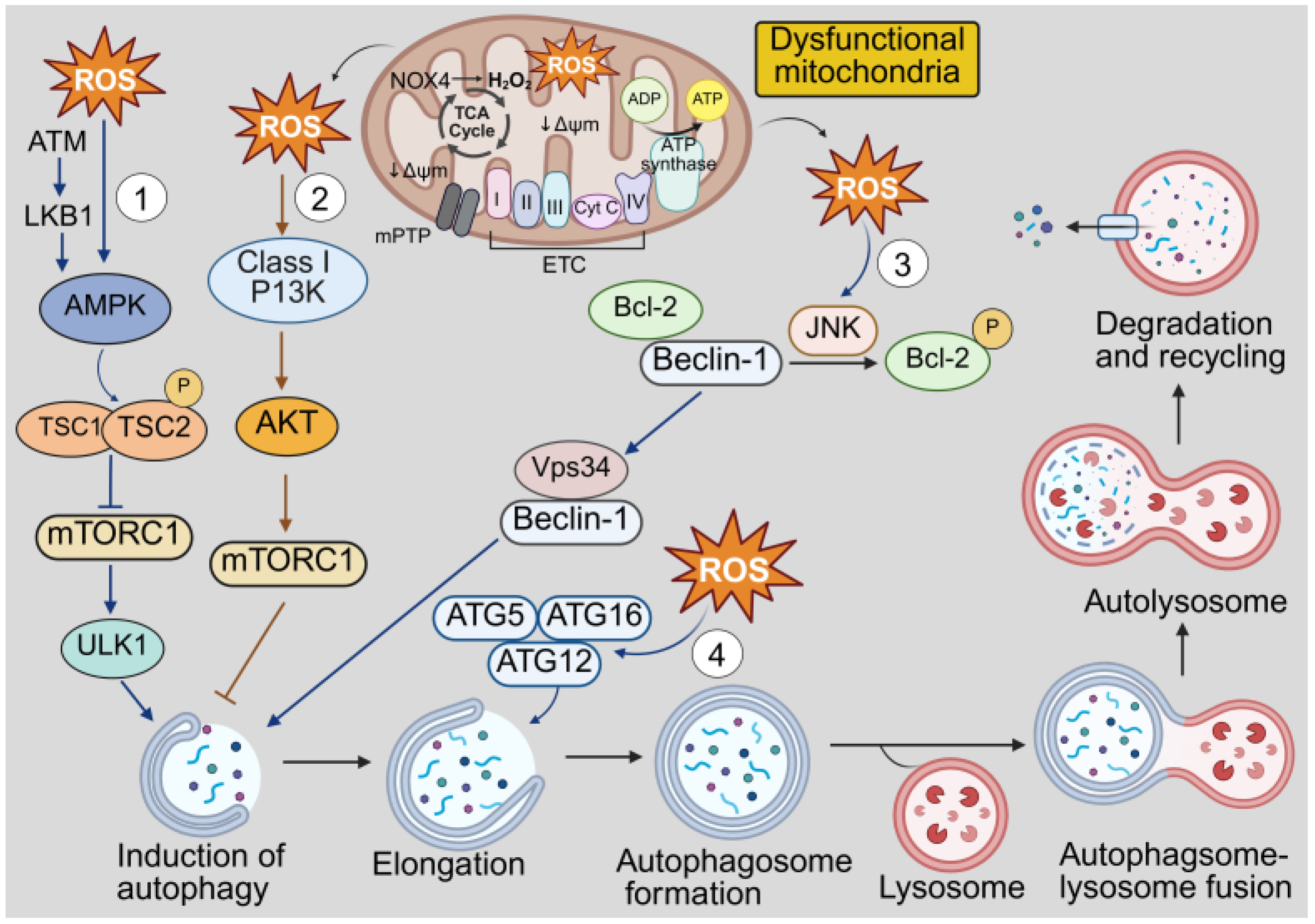

7. The Crosstalk Between Redox Signaling and Autophagy

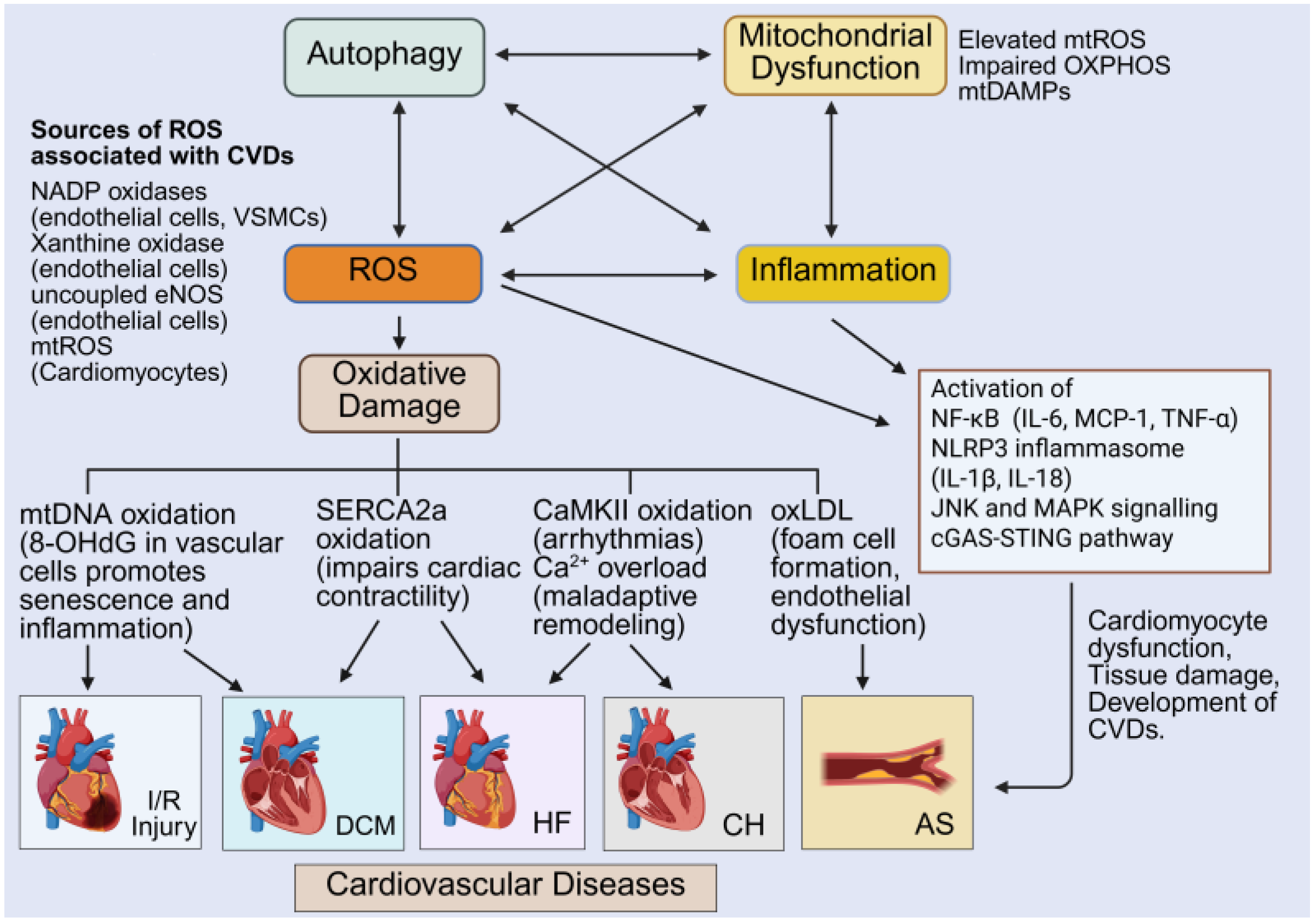

8. Interconnected Signaling and Feedback Loops: The Redox-Mitochondria–Autophagy–Inflammation Axis

9. Interplay of Autophagy, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cellular Redox States in the Context of CVDs

9.1. Atherosclerosis

9.2. Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy

9.3. Ischemia–Reperfusion (I/R) Injury

9.4. Heart Failure

9.5. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

10. Refining Redox Approaches for CVD: From Vitamins to Precision Therapies

11. Therapeutic Implications and Challenges

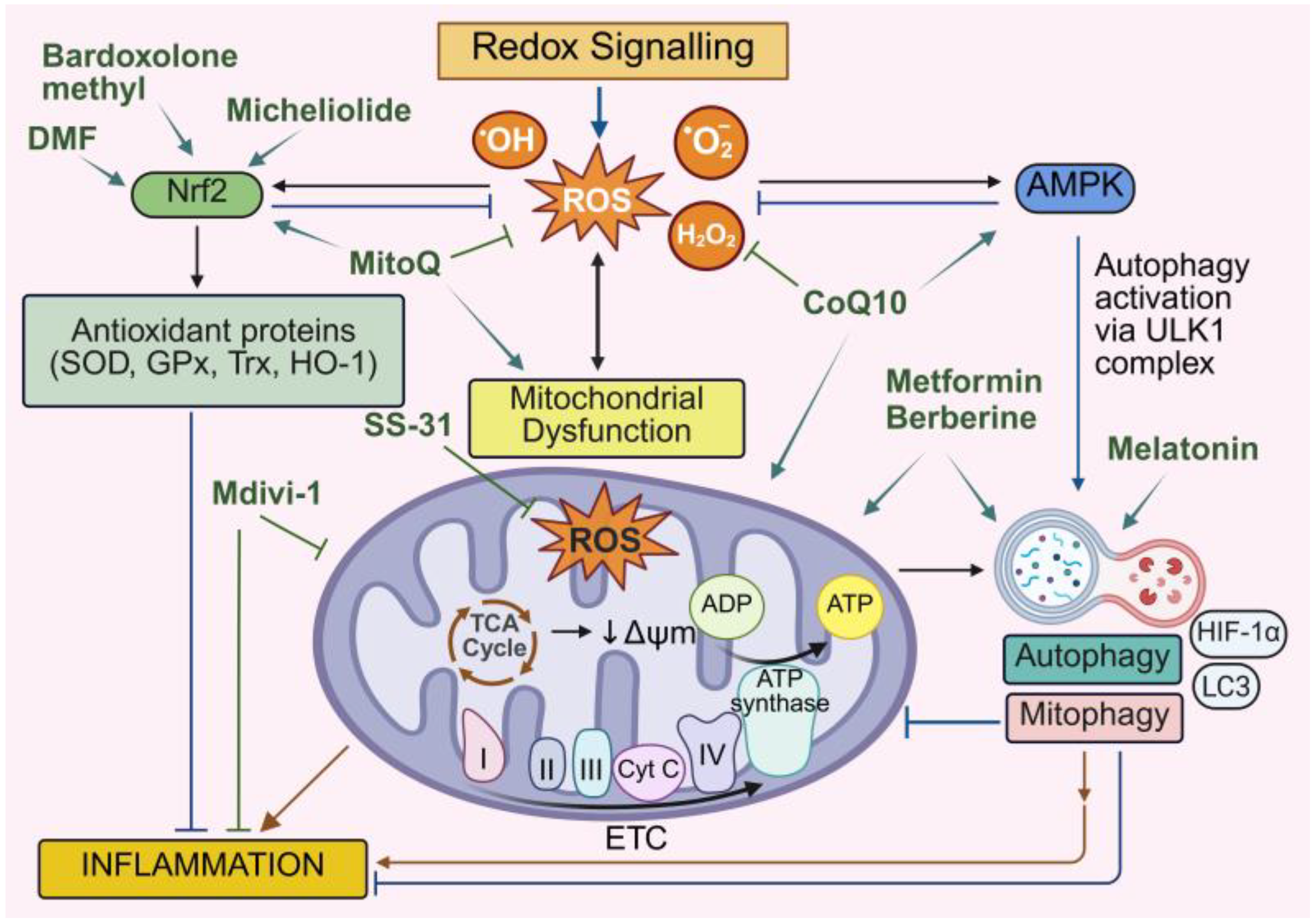

11.1. Targeting the Oxidative Stress–Mitochondria–Autophagy–Inflammation Axis

11.2. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Disease

11.3. Therapies Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Autophagy in Cardiovascular Disease

11.3.1. CoQ10

11.3.2. MitoQ

11.3.3. Melatonin

11.3.4. Urolithin A

11.3.5. Elamipretide

11.3.6. Metformin

11.3.7. Berberine

| Therapeutic Agent | Signaling Pathways and Related Mechanisms | Treatment Outcome | Experimental Models | Disease Context | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoQ10 | Inhibits oxidative stress. Improves mitochondrial function. Activates the AMPK-YAP-OPA1 pathway. | Increases SOD and GSH in serum in diseased mice. Suppresses the expression of IL-6, TNF-α, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and NLRP3. Ameliorates atherosclerosis. | High-fat diet (HFD)-fed ApoE−/− mice | Atherosclerosis | [27] |

| Reduces oxidative stress. Enhances autophagy. | Increases GPx, GR, SOD and GSH. Decreases TBARS in myocardial tissue in rats with AMI. Increases autophagy proteins Beclin-1 and Atg5. Reduces infarct size. Improves cardiac function. | AMI/R Sprague–Dawley (SD) rat model | Acute myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury (AMI) | [288] | |

| MitoQ | Reduces oxidative stress. Activates p62-Nrf2 signaling pathway. | Decreases ROS accumulation. Improves cell viability. Reduces cardiotoxicity. | Triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity in rat cardiomyocyte H9c2 cells | [293] | |

| Decreases oxidative stress. Regulates mitochondrial function. | Restores mitochondrial membrane potential and respiration. Improves mitochondrial calcium retention capacity. Inhibits ROS production. Improves cardiac function. | Rat model of heart failure induced by pressure overload | Heart failure | [291] | |

| Enhances mitophagy via PINK1/Parkin pathway. | Reduces myocardial infarction, myocardial pathological damage and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Improves cardiac function. | Myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in Type 2 diabetic rats | MIR injury in Type 2 diabetes (T2D) | [29] | |

| Melatonin | Suppresses oxidative stress. Enhances mitochondrial biogenesis via the AMPK/PGC1α pathway. | Reduces mtROS production. Alters mitochondrial morphology of cardiomyocytes. Attenuates myocardial damage. | Hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in cardiomyocytes | Cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury | |

| Reduces inflammation. Enhances autophagy. Promotes TFEB nuclear translocation. Inhibits NF-κB by inhibiting Gal-3. | Inhibits secretion of IL-6, IL-18, IL-1β and TNF-α in arteries. Inhibits atherosclerotic plaque progression. | HFD-fed ApoE−/− mice | Atherosclerosis | [28] | |

| Urolithin A | Restores mitochondrial dynamics proteins DRP1 and MFN1. Activates mitochondrial recycling and quality control (QC). | Improves heart mitochondrial ultrastructure, morphology and function. Enhances cardiac function and skeletal muscle force in aging. | Non-diseased old C57BL/6RJ mice | Aging | [30] |

| Promotes mitochondrial QC pathways. | Improves systolic function. Improves cardiac function and mitochondrial health. | Rat model of chronic heart failure (HFrEF) | Heart failure | [30] | |

| Elamipretide (SS-31) | Regulates age-associated post-translational modifications of heart proteins. | Affects mouse heart function. | Aged mouse hearts | Cardiac aging | [301] |

| Suppresses mtROS production. Inhibits protein oxidation and cellular senescence. | Reduces cardiac hypertrophy. Improves cardiac function. | Aged mice | Myocardial hypertrophy | [302] | |

| Metformin | Preserves mitochondrial function. | Alleviates mitochondrial dynamic imbalance and apoptosis. Reduces arrhythmia and infarct size. Improves cardiac function. | Cardiac I/R injury in Wistar rats | Cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury | [98] |

| Induces autophagy. | Enhances epicardial, endocardial and vascular endothelial regeneration. Improves transient collagen deposition and resolution. Induces cardiomyocyte proliferation. Improves systolic function of the heart. | Adult zebrafish model of heart cryoinjury | Myocardial infarction | [305] | |

| Berberine | Inhibits inflammatory responses and oxidative stress via miR-26b-5p-mediated PTGS2/MAPK. | Increases GSH, GSH-Px and SOD. Suppresses MDA, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6. Preserves myocardial structure. Improves cardiac function. | OGD/R-treated cardiomyocytes Rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury | Acute myocardial infarction model (AMI) | [279] |

| Activates autophagy and reduces inflammation. Modulates RAGE-NF-κB. | Increases lipid accumulation and foam cell formation. Maintains vascular endothelial cell integrity. Reduces atherosclerotic inflammation. | High-fat diet ApoE−/− mouse model | Atherosclerosis | [278] | |

| Regulates PI3K/AKT/mTOR. | Improves intimal hyperplasia. Reduces carotid lipid accumulation. Promotes cell proliferation. | High-fat diet ApoE−/− mice | Carotid atherosclerosis | [309] | |

| Mdivi-1 | Suppresses mt-ROS/NLRP3 by inhibiting DRP1-dependent mitochondrial fission. | Decreases plaque area. Reduces foam cells. Inhibits M1 polarization. Inhibits activation of NLRP3. | High-fat diet ApoE−/− mice | Atherosclerosis | [97] |

| DMF | Exerts antioxidant effects by activating the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. | Reduces the area of aortic atherosclerosis. Decreases serum and aortic ROS, HO-1, NF-κB, ICAM-1 and gp91phox. Increases serum and aortic Nrf2, eNOS and p-eNOS. | ApoE−/− mice with streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia | Atherosclerosis | [281] |

| Micheliolide (MCL) | Promotes KEAP1/Nrf2 dissociation. Activates Nrf2 pathway. | Decreases inflammatory responses. Reduces oxidative stress. Inhibits macrophage ferroptosis. | High-fat diet ApoE−/− mice | Atherosclerosis | [105] |

| Bardoxolone- methyl | Increases Nrf2 binding to the CREB-binding protein. Increases Nrf2 downstream targets NQO1, HO-1 and CAT. | Reduces myocardial oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. Attenuates myocardial inflammation. | Rat model of chronic heart failure | Chronic heart failure | [282] |

12. Discussion

13. Conclusions

Novelty

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin II-converting enzyme |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| AMI | Acute myocardial infraction |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANT1 | Adenine nucleotide translocase 1 |

| ApoE−/− | Apolipoprotein E-deficient |

| ARBs | Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| AREs | Antioxidant response elements |

| ASC | Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD |

| ATM | Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated |

| BNIP3 | Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3 |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| Caspase-1 | Cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase-1 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CBP | Transcriptional coactivator CREB-binding protein |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CoQ10 | Coenzyme Q10 |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CypD | Cyclophilin D |

| cytoROS | Cytosolic ROS |

| DCM | Diabetic cardiomyopathy |

| DMF | Dimethyl fumarate |

| DMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DRP1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Gal-3 | Galectin-3 |

| GCLC | Glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic |

| GeX1 | Gerontoxanthone I |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSNOR | S-nitrosoglutathione reductase |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| HAECs | Human aortic endothelial cells |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| Hsp70 | Heat shock protein 70 |

| I/R | Ischemia–reperfusion |

| IKKβ | Inhibitor kappa-B kinaseβ |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-16 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LKB1 | Liver kinase B1 |

| LOX-1 | Lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor |

| LTF | Lactoferrin |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| MAO-A | Monoamine oxidase A |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCL | Micheliolide |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 |

| MCU | Mitochondrial calcium uniporter |

| McX | Macluraxanthone |

| MD1 | Myeloid differentiation protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| Mdivi-1 | Mitochondrial division inhibitor 1 |

| MFN1 | Mitofusins 1 |

| MFN2 | Mitofusins 2 |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| Mito-Esc | Mitochondria-targeted esculetin |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| MsrA | Methionine sulfoxide reductase A |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mtKATP | Mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium K channel |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial ROS |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NEK7 | NIMA-associated kinase 7 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3 |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthases |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| Nt-R | N-terminal arginine |

| 1O2 | Singlet oxygen |

| O2•− | Superoxide |

| O8G | 8-oxoguanosine |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radicals |

| OGD/R | Oxygen–glucose deprivation/re-oxygen |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy 1 |

| ox-LDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 |

| PDE5 | Phosphodiesterase 5 |

| Prx | Peroxiredoxin |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROMO1 | Reactive oxygen species modulator 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RSS | Reactive sulfur species |

| RV | Right ventricular |

| Sirt1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| SLC26A4 | Solute carrier family 26 member 4 |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SR-1 | Scavenger receptor-1 |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| TAC | Transverse aortic constriction |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TPP+ | Triphenylphosphonium cation |

| Trx | Thioredoxin |

| TRXox | Oxidized thioredoxin |

| TRXred | Reduced thioredoxin |

| ULK1 | Autophagy-activating kinase 1 |

| Vcp | Valosin-containing protein |

| VDAC1 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| XO | Xanthine oxidase |

| XOR | Xanthine oxidoreductase |

| ZDHHC13 | Zinc finger DHHC-type palmitoyltransferase 13 |

| ΔΨm | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

References

- Goh, R.S.J.; Chong, B.; Jayabaskaran, J.; Jauhari, S.M.; Chan, S.P.; Kueh, M.T.W.; Shankar, K.; Li, H.; Chin, Y.H.; Kong, G.; et al. The burden of cardiovascular disease in Asia from 2025 to 2050: A forecast analysis for East Asia, South Asia, South-East Asia, Central Asia, and high-income Asia Pacific regions. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 49, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, B.; Jayabaskaran, J.; Jauhari, S.M.; Chan, S.P.; Goh, R.; Kueh, M.T.W.; Li, H.; Chin, Y.H.; Kong, G.; Anand, V.V.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, S.D.; Khera, R.; Zafar, S.Y.; Nasir, K.; Warraich, H.J. Financial burden, distress, and toxicity in cardiovascular disease. Am. Heart J. 2021, 238, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Schmidlin, T. Recent advances in cardiovascular disease research driven by metabolomics technologies in the context of systems biology. NPJ Metab. Health Dis. 2024, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.; Parthasarathy, S.; Carew, T.E.; Khoo, J.C.; Witztum, J.L. Beyond cholesterol. Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Khan-Merchant, N.; Penumetcha, M.; Khan, B.V.; Santanam, N. Did the antioxidant trials fail to validate the oxidation hypothesis? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2001, 3, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, N.; van Dam, R.M.; Koh, W.P.; Chen, C.; Lee, Y.P.; Yuan, J.M.; Ong, C.N. Plasma vitamin E and coenzyme Q10 are not associated with a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction in Singapore Chinese adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Shiekh, Y.; Lawrence, J.A.; Ezekwueme, F.; Alam, M.; Kunwar, S.; Gordon, D.K. A Systematic Review of Effects of Vitamin E on the Cardiovascular System. Cureus 2021, 13, e15616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Mailloux, R.J.; Jakob, U. Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ming, H.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Huang, C. Redox regulation: Mechanisms, biology and therapeutic targets in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennicke, C.; Cocheme, H.M. Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Findings in redox biology: From H2O2 to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13458–13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.T.; Singh, A.K.; Knaus, U.G. Redox regulator network in inflammatory signaling. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2019, 9, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galley, J.C.; Straub, A.C. Redox Control of Vascular Function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, e178–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, J.; Kopf, M. Redox regulation of immunometabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.J.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, E.K.; Park, S.I.; Lee, S.J. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, B.U.; Habib, S.; Ahmad, P.; Allarakha, S.; Moinuddin; Ali, A. Pathophysiological Role of Peroxynitrite Induced DNA Damage in Human Diseases: A Special Focus on Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP). Indian. J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; Touyz, R.M.; Zweier, J.L.; Dikalov, S.; Chilian, W.; Chen, Y.R.; Harrison, D.G.; Bhatnagar, A.; American Heart Association Council on Basic Cardiovascular, S. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species, Reactive Nitrogen Species, and Redox-Dependent Signaling in the Cardiovascular System: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, e39–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, V.; Pradhan, P.; Braud, L.; Fuchs, H.R.; Gueler, F.; Motterlini, R.; Foresti, R.; Immenschuh, S. Human and murine macrophages exhibit differential metabolic responses to lipopolysaccharide-A divergent role for glycolysis. Redox Biol. 2019, 22, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.; Mills, E.L. Redox regulation of macrophages. Redox Biol. 2024, 72, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, G.K.; Shen, X.; Kevil, C.G. Reactive Sulfur Species: A New Redox Player in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, G.K.; Shackelford, R.E.; Shen, X.; Dominic, P.; Kevil, C.G. Sulfide regulation of cardiovascular function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, A.; Tang, X.; Zhou, L.; Ito, T.; Kato, Y.; Nishida, M. Sulfur metabolism as a new therapeutic target of heart failure. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 155, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, R.; Sun, X.; Chen, G. Sulfur signaling pathway in cardiovascular disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1303465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hu, Q.; Tan, B.; Rose, P.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, Y.Z. Amelioration of mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure through S-sulfhydration of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Redox Biol. 2018, 19, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, T.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Sun, H. CoenzymeQ10-Induced Activation of AMPK-YAP-OPA1 Pathway Alleviates Atherosclerosis by Improving Mitochondrial Function, Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Promoting Energy Metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Kou, J.; Song, D.; Yu, X.; Dong, B.; Chen, T.; Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; et al. Melatonin inhibits atherosclerosis progression via galectin-3 downregulation to enhance autophagy and inhibit inflammation. J. Pineal Res. 2023, 74, e12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Leng, Y.; Lei, S.; Qiu, Z.; Ming, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Wu, Y.; Xia, Z. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in type 2 diabetic rats. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2022, 27, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Faitg, J.; Tissot, C.; Konstantopoulos, D.; Laws, R.; Bourdier, G.; Andreux, P.A.; Davey, T.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Ivanisevic, J.; et al. Urolithin A provides cardioprotection and mitochondrial quality enhancement preclinically and improves human cardiovascular health biomarkers. iScience 2025, 28, 111814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristow, M. Unraveling the truth about antioxidants: Mitohormesis explains ROS-induced health benefits. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.C.; Case, A.J. Redox biology in physiology and disease. Redox Biol. 2019, 27, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peoples, J.N.; Saraf, A.; Ghazal, N.; Pham, T.T.; Kwong, J.Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canton, M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Spera, I.; Venegas, F.C.; Favia, M.; Viola, A.; Castegna, A. Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages: Sources and Targets. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 734229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, F.; Francia, P.; Camici, G.G.; Pelicci, P.G.; Luscher, T.F.; Volpe, M. Final common molecular pathways of aging and cardiovascular disease: Role of the p66Shc protein. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslem, L.; Hays, J.M.; Hays, F.A. p66Shc in Cardiovascular Pathology. Cells 2022, 11, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, I.; Motohashi, H.; Dallenga, T.; Schaible, U.E.; Benhar, M. Redox signaling in innate immunity and inflammation: Focus on macrophages and neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, S.; Awad, M.; Harrington, E.O.; Sellke, F.W.; Abid, M.R. Subcellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, E.; Torina, A.; Reichert, K.; Colantuono, B.; Nur, N.; Zeeshan, K.; Ravichandran, V.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Zeeshan, K.; et al. Mitochondrial redox plays a critical role in the paradoxical effects of NAPDH oxidase-derived ROS on coronary endothelium. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, F.; Mattevi, A. Structure and mechanisms of ROS generation by NADPH oxidases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 59, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishy, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chung, H.S.; Riehle, C.; Soto, J.; Jenkins, S.; Abel, P.; Cowart, L.A.; Van Eyk, J.E.; Abel, E.D. Lipid-induced NOX2 activation inhibits autophagic flux by impairing lysosomal enzyme activity. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.P.; Di Marco, E.; Okabe, J.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Heitz, F.; Montezano, A.C.; de Haan, J.B.; Koulis, C.; El-Osta, A.; Andrews, K.L.; et al. NADPH oxidase 1 plays a key role in diabetes mellitus-accelerated atherosclerosis. Circulation 2013, 127, 1888–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligeon, L.A.; Pena-Francesch, M.; Vanoaica, L.D.; Nunez, N.G.; Talwar, D.; Dick, T.P.; Munz, C. Oxidation inhibits autophagy protein deconjugation from phagosomes to sustain MHC class II restricted antigen presentation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoboue, E.D.; Sitia, R.; Simmen, T. Redox crosstalk at endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane contact sites (MCS) uses toxic waste to deliver messages. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moris, D.; Spartalis, M.; Spartalis, E.; Karachaliou, G.S.; Karaolanis, G.I.; Tsourouflis, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Tzatzaki, E.; Theocharis, S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the clinical significance of myocardial redox. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: The latest update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, L.R.; Leichert, L.I. Global approaches for protein thiol redox state detection. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 77, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.C.; Mieyal, J.J. Glutathione and Glutaredoxin-Key Players in Cellular Redox Homeostasis and Signaling. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Yaguchi, N.; Iijima, T.; Muramatsu, A.; Baird, L.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M. Sensor systems of KEAP1 uniquely detecting oxidative and electrophilic stresses separately In vivo. Redox Biol. 2024, 77, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Runge, M.S. Redox signaling in cardiovascular health and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Wang, S.B.; Venkatraman, V.; Murray, C.I.; Van Eyk, J.E. Cysteine oxidative posttranslational modifications: Emerging regulation in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Liu, J.; Finkel, T. Mitohormesis. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.R.; Cotter, T.G. Hydrogen peroxide: A Jekyll and Hyde signalling molecule. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Witting, P.K.; Drummond, G.R. Redox control of endothelial function and dysfunction: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1713–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Deng, N.; Tian, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Z. The role of ROS-induced pyroptosis in CVD. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.I.; Griendling, K.K. Regulation of signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, G.Z.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Tabas, I. Macrophage mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atherosclerosis and nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated inflammation in macrophages. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Q.; Ma, H.; Zou, J.; Wang, W.; Zhu, L.; Deng, H.; Meng, M.; Tan, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, X.; et al. Metformin protects against ischaemic myocardial injury by alleviating autophagy-ROS-NLRP3-mediated inflammatory response in macrophages. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 145, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Rizky, L.; Stefanovic, N.; Tate, M.; Ritchie, R.H.; Ward, K.W.; de Haan, J.B. The nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) activator dh404 protects against diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.T.; Li, X.Y.; Zhu, H.Z.; Xie, Y.H.; Wang, S.W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Carvacrol alleviates LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB and NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes. J. Inflamm. 2024, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziehr, B.K.; MacDonald, J.A. Regulation of NLRPs by reactive oxygen species: A story of crosstalk. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yazdi, A.S.; Menu, P.; Tschopp, J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2011, 469, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, L.; Xiao, Z.; Rao, F.; Yakupu, W.; Rouzi, A.; Cheng, K.; Pang, Y.; Su, Y.; Wu, D. Kirenol attenuates pressure overload-induced heart failure by enhancing autophagy in macrophages. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 440, 133681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Cui, L.; White, J.; Kuck, J.; Ruchko, M.V.; Wilson, G.L.; Alexeyev, M.; Gillespie, M.N.; Downey, J.M.; Cohen, M.V. Mitochondrially targeted Endonuclease III has a powerful anti-infarct effect in an in vivo rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 2015, 110, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, M.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, X.; Sarapultsev, A.; Luo, S.; Hu, D. Mitochondrial DNA Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Novel Therapeutic Target. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Nikiforov, N.G.; Markin, A.M.; Kashirskikh, D.A.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Gerasimova, E.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Overview of OxLDL and Its Impact on Cardiovascular Health: Focus on Atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 613780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermayer, G.; Afonyushkin, T.; Binder, C.J. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein in inflammation-driven thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Khismatullin, D.B. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein contributes to atherogenesis via co-activation of macrophages and mast cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Hu, X.; Fu, W. Bone marrow NLRP3 inflammasome-IL-1beta signal regulates post-myocardial infarction megakaryocyte development and platelet production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 585, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, D.J.; Goldstein, D.R. Ageing and atherosclerosis: Vascular intrinsic and extrinsic factors and potential role of IL-6. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, P.; Buckley, D.J.; Greaney, J.L.; Case, A.J.; Fadel, P.J.; Trott, D.W. IL-6 induces mitochondrial ROS production and blunts NO bioavailability in human aortic endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2025, 328, R509–R514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, V.C.; Bahl, J.J.; Chen, Q.M. Signals of oxidant-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy: Key activation of p70 S6 kinase-1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 300, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniyama, Y.; Ushio-Fukai, M.; Hitomi, H.; Rocic, P.; Kingsley, M.J.; Pfahnl, C.; Weber, D.S.; Alexander, R.W.; Griendling, K.K. Role of p38 MAPK and MAPKAPK-2 in angiotensin II-induced Akt activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C494–C499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.M.; Sharma, A.; Stefanovic, N.; Yuen, D.Y.; Karagiannis, T.C.; Meyer, C.; Ward, K.W.; Cooper, M.E.; de Haan, J.B. Derivative of bardoxolone methyl, dh404, in an inverse dose-dependent manner lessens diabetes-associated atherosclerosis and improves diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3091–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Ding, W.; Ji, X.; Ao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, J. Oxidative Stress in Cell Death and Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9030563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando-Rodriguez, G.E.; Gibson, S.B. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Regulates Different Types of Cell Death by Acting as a Rheostat. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9912436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, K.; Jiang, H.; Zou, Y.; Song, C.; Cao, K.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, D.; Zhang, N.; et al. Programmed death of cardiomyocytes in cardiovascular disease and new therapeutic approaches. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, G.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Tong, C.; Fan, D.; Du, F.; Yu, H. PEP-1-MsrA ameliorates inflammation and reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.S.; Pan, B.Y.; Tsai, P.H.; Chen, F.Y.; Yang, W.C.; Shen, M.Y. Kansuinine A Ameliorates Atherosclerosis and Human Aortic Endothelial Cell Apoptosis by Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Suppressing IKKbeta/IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Xie, E.; Yang, X.; Wei, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhu, N.; Yin, X.; et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Men, H.; Bao, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Keller, B.B.; Tong, Q.; et al. Ferroptosis is essential for diabetic cardiomyopathy and is prevented by sulforaphane via AMPK/NRF2 pathways. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: From mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.K. Antimycin-insensitive oxidation of succinate and reduced nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in electron-transport particles. I. pH dependency and hydrogen peroxide formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1966, 122, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschen, G.; Flohe, L.; Chance, B. Respiratory chain linked H2O2 production in pigeon heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1971, 18, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschen, G.; Azzi, A.; Richter, C.; Flohe, L. Superoxide radicals as precursors of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 1974, 42, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolotto Dos Reis, F.H. Mitochondria and the heart. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1963–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, R.; Gustafsson, A.B. Mitochondrial quality control in cardiomyocytes: Safeguarding the heart against disease and ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.D.; Li, C.Q.; Wang, H.W.; Zheng, M.M.; Chen, Q.W. Inhibition of DRP1-dependent mitochondrial fission by Mdivi-1 alleviates atherosclerosis through the modulation of M1 polarization. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palee, S.; Higgins, L.; Leech, T.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. Acute metformin treatment provides cardioprotection via improved mitochondrial function in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S.; McClintock, D.S.; Feliciano, C.E.; Wood, T.M.; Melendez, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Schumacker, P.T. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: A mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 25130–25138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.L.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Maitland, M.L.; Rich, S.; Garcia, J.G.; Weir, E.K. Mitochondrial metabolism, redox signaling, and fusion: A mitochondria-ROS-HIF-1alpha-Kv1.5 O2-sensing pathway at the intersection of pulmonary hypertension and cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H570–H578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H.; Honda, S.; Maeda, S.; Chang, L.; Hirata, H.; Karin, M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 2005, 120, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cui, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.X.; Su, Y.D.; Li, S.N.; Wang, L.L.; Zhao, Y.W.; Wang, S.X.; Yan, F.; et al. ATP6AP2 knockdown in cardiomyocyte deteriorates heart function via compromising autophagic flux and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariappan, N.; Elks, C.M.; Sriramula, S.; Guggilam, A.; Liu, Z.; Borkhsenious, O.; Francis, J. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 85, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Chen, M. The role of mitochondria-associated membranes mediated ROS on NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1059576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, B.; Bai, X.; Weng, X.; Xu, J.; Tao, Y.; Yang, D.; et al. MCL attenuates atherosclerosis by suppressing macrophage ferroptosis via targeting KEAP1/NRF2 interaction. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, K.; Bugger, H.; Wende, A.R.; Soto, J.; Jenson, G.A.; Tor, A.R.; McGlauflin, R.; Kenny, H.C.; Zhang, Y.; Souvenir, R.; et al. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Lipotoxic Hearts Induce Post-Translational Modifications of AKAP121, DRP1, and OPA1 That Promote Mitochondrial Fission. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.Y.; Wei, X.X.; Zhi, X.L.; Wang, X.H.; Meng, D. Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission in cardiovascular disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, I.; Innis-Whitehouse, W.; Lopez, A.; Keniry, M.; Gilkerson, R. Oxidative insults disrupt OPA1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics in cultured mammalian cells. Redox Rep. 2018, 23, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehaitly, A.; Guihot, A.L.; Proux, C.; Grimaud, L.; Aurriere, J.; Legouriellec, B.; Rivron, J.; Vessieres, E.; Tetaud, C.; Zorzano, A.; et al. Altered Mitochondrial Opa1-Related Fusion in Mouse Promotes Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, P.; Chen, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zou, D.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Lin, Z. Mitochondrial ROS promote macrophage pyroptosis by inducing GSDMD oxidation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 11, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devant, P.; Borsic, E.; Ngwa, E.M.; Xiao, H.; Chouchani, E.T.; Thiagarajah, J.R.; Hafner-Bratkovic, I.; Evavold, C.L.; Kagan, J.C. Gasdermin D pore-forming activity is redox-sensitive. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evavold, C.L.; Hafner-Bratkovic, I.; Devant, P.; D’Andrea, J.M.; Ngwa, E.M.; Borsic, E.; Doench, J.G.; LaFleur, M.W.; Sharpe, A.H.; Thiagarajah, J.R.; et al. Control of gasdermin D oligomerization and pyroptosis by the Ragulator-Rag-mTORC1 pathway. Cell 2021, 184, 4495–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Dai, S.; Zhong, L.; Shi, X.; Fan, X.; Zhong, X.; Lin, W.; Su, L.; Lin, S.; Han, B.; et al. GSDMD (Gasdermin D) Mediates Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy and Generates a Feed-Forward Amplification Cascade via Mitochondria-STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) Axis. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2505–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Gao, Y.; Dong, Z.; Yang, J.; Gao, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. GSDMD-Mediated Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis Promotes Myocardial I/R Injury. Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Luan, J.; Xu, C.; Wu, Z.; Ju, D.; Hu, W. GSDMD contributes to myocardial reperfusion injury by regulating pyroptosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 893914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.J.; Mishra, R.; Schneider, K.S.; Medard, G.; Wettmarshausen, J.; Dittlein, D.C.; Shi, H.; Gorka, O.; Koenig, P.A.; Fromm, S.; et al. K+ Efflux-Independent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Small Molecules Targeting Mitochondria. Immunity 2016, 45, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhan, X.; Tang, M.; Fina, M.; Su, L.; Pratt, D.; Bu, C.H.; Hildebrand, S.; et al. NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.M.; Hooftman, A.; Angiari, S.; Tummala, P.; Zaslona, Z.; Runtsch, M.C.; McGettrick, A.F.; Sutton, C.E.; Diskin, C.; Rooke, M.; et al. Glutathione Transferase Omega-1 Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through NEK7 Deglutathionylation. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, W.; Tao, L.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, R. Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor-2 Negatively Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity by Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced NLRP3 Priming. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Foster, D.B.; Rucker, J.; O’Rourke, B.; Kass, D.A.; Van Eyk, J.E. Redox regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase: Implications for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, M.; Pinton, P.; Rizzuto, R. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in health and disease. Biol. Res. 2004, 37, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Song, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, A.; Shi, G.; Wang, Q.; Gu, L.; Liu, M.; Xie, L.H.; Qu, Z.; et al. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Influx Contributes to Arrhythmic Risk in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, 657a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patron, M.; Granatiero, V.; Espino, J.; Rizzuto, R.; De Stefani, D. MICU3 is a tissue-specific enhancer of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Tomar, D.; Siddiqui, N.; Lynch, S.; Nemani, N.; Breves, S.L.; Zhang, X.; Tripathi, A.; Palaniappan, P.; et al. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uniporter Is a Mitochondrial Luminal Redox Sensor that Augments MCU Channel Activity. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomeni, G.; De Zio, D.; Cecconi, F. Oxidative stress and autophagy: The clash between damage and metabolic needs. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, J.E.; Wilson, N.; Son, S.M.; Obrocki, P.; Wrobel, L.; Rob, M.; Takla, M.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Autophagy, aging, and age-related neurodegeneration. Neuron 2025, 113, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzych, K.R.; Klionsky, D.J. An overview of autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 20, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, A.K.; Strub, M.P.; Piszczek, G.; Tjandra, N. Structure of transmembrane domain of lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2a (LAMP-2A) reveals key features for substrate specificity in chaperone-mediated autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 35111–35123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wible, D.J.; Bratton, S.B. Reciprocity in ROS and autophagic signaling. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, K.; Imai, K.; Fukuda, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kunugi, H.; Fujita, T.; Kaminishi, T.; Tischer, C.; Neumann, B.; Reither, S.; et al. Palmitoylation of ULK1 by ZDHHC13 plays a crucial role in autophagy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Virgilio, L.; Silva-Lucero, M.D.; Flores-Morelos, D.S.; Gallardo-Nieto, J.; Lopez-Toledo, G.; Abarca-Fernandez, A.M.; Zacapala-Gomez, A.E.; Luna-Munoz, J.; Montiel-Sosa, F.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; et al. Autophagy: A Key Regulator of Homeostasis and Disease: An Overview of Molecular Mechanisms and Modulators. Cells 2022, 11, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holczer, M.; Hajdu, B.; Lorincz, T.; Szarka, A.; Banhegyi, G.; Kapuy, O. Fine-tuning of AMPK-ULK1-mTORC1 regulatory triangle is crucial for autophagy oscillation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, R.C.; Yuan, H.X.; Guan, K.L. Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Kominami, E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008, 445, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.G.; Hurley, J.H. Structure and function of the ULK1 complex in autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016, 39, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cao, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Fang, X.; Jia, S.; Ye, J.; Liu, Y.; Weng, L.; et al. Mitophagy-regulated mitochondrial health strongly protects the heart against cardiac dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Weinheimer, C.J.; Kovacs, A.; Finck, B.; Diwan, A.; Mann, D.L. Targeting the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway in a Pathophysiologically Relevant Murine Model of Reversible Heart Failure. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2022, 7, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, V.; Hawkins, W.D.; Klionsky, D.J. Watch What You (Self-) Eat: Autophagic Mechanisms that Modulate Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell 2014, 159, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornatowski, W.; Lu, Q.; Yegambaram, M.; Garcia, A.E.; Zemskov, E.A.; Maltepe, E.; Fineman, J.R.; Wang, T.; Black, S.M. Complex interplay between autophagy and oxidative stress in the development of pulmonary disease. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Interactions between reactive oxygen species and autophagy: Special issue: Death mechanisms in cellular homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alers, S.; Loffler, A.S.; Wesselborg, S.; Stork, B. Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: Cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Mo, L.; Niu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Xu, X. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Autophagy in Periodontitis and Their Potential Linkage. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhou, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, L.; Feng, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Jing, W.; Wang, T.; Su, H.; et al. The role of autophagy in cardiovascular disease: Cross-interference of signaling pathways and underlying therapeutic targets. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1088575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, L.X.; Xie, S.P. Autophagy in cardiac pathophysiology: Navigating the complex roles and therapeutic potential in cardiac fibrosis. Life Sci. 2025, 123761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, D.H. Redefining the role of AMPK in autophagy and the energy stress response. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Bisaglia, M.; Plotegher, N. Linking ROS Levels to Autophagy: The Key Role of AMPK. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Cai, S.L.; Kim, J.; Nanez, A.; Sahin, M.; MacLean, K.H.; Inoki, K.; Guan, K.L.; Shen, J.; Person, M.D.; et al. ATM signals to TSC2 in the cytoplasm to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4153–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duan, J.; Liao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Gu, H.; Yang, P.; Fu, D.; et al. Shengjie Tongyu Decoction Regulates Cardiomyocyte Autophagy Through Modulating ROS-PI3K/Akt/mTOR Axis by LncRNA H19 in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Kou, J.; Han, X.; Li, X.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, L. ROS-Dependent Activation of Autophagy through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway Is Induced by Hydroxysafflor Yellow A-Sonodynamic Therapy in THP-1 Macrophages. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8519169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Feng, J.; Wu, Y.; Shen, H.M.; Lu, G.D. Full-coverage regulations of autophagy by ROS: From induction to maturation. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, S.R.; Gordon, B.S.; Moyer, J.E.; Dennis, M.D.; Jefferson, L.S. Leucine induced dephosphorylation of Sestrin2 promotes mTORC1 activation. Cell. Signal. 2016, 28, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.C.; Liu, P.F.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Shu, C.W. The interplay of autophagy and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and therapy of retinal degenerative diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, Z.; Gu, Q.; Xia, F.; Fu, Y.; Liu, P.; Yin, X.M.; Li, M. The protease activity of human ATG4B is regulated by reversible oxidative modification. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1838–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.; Otten, E.G.; Manni, D.; Stefanatos, R.; Menzies, F.M.; Smith, G.R.; Jurk, D.; Kenneth, N.; Wilkinson, S.; Passos, J.F.; et al. Oxidation of SQSTM1/p62 mediates the link between redox state and protein homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Enaka, M.; Muragaki, Y. Activation of KEAP1/NRF2/P62 signaling alleviates high phosphate-induced calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells by suppressing reactive oxygen species production. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.R.; Zhang, M.H.; Chen, Y.J.; Sun, Y.L.; Gao, Z.M.; Li, Z.J.; Zhang, G.P.; Qin, Y.; Dai, X.Y.; Yu, X.Y.; et al. Urolithin A ameliorates obesity-induced metabolic cardiomyopathy in mice via mitophagy activation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Goh, J.Y.; Xiao, L.; Xian, H.; Lim, K.L.; Liou, Y.C. Reactive oxygen species trigger Parkin/PINK1 pathway-dependent mitophagy by inducing mitochondrial recruitment of Parkin. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16697–16708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Tan, E.K. Oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent mitochondrial deacetylase sirtuin-3 as a potential therapeutic target of Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 62, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J.H.; Schafer, Z.T. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitophagy: A Complex and Nuanced Relationship. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Cheng, J.; Qu, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, L. Effects of mitochondrial dysfunction on cellular function: Role in atherosclerosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, K.P.; Michalak, A.Z. Understanding chronic inflammation: Couplings between cytokines, ROS, NO, Cai2+, HIF-1alpha, Nrf2 and autophagy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1558263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Lei, J.; Han, H.; Li, W.; Qu, Y.; Fu, E.; Fu, F.; Wang, X. SIRT1 protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via activating eNOS in diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2015, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.J.; Zhang, T.N.; Chen, H.H.; Yu, X.F.; Lv, J.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.Q.; Wei, Y.F.; et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, D.; Ping, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y. SIRT1 mediates the inflammatory response of macrophages and regulates the TIMP3/ADAM17 pathway in atherosclerosis. Exp. Cell Res. 2024, 442, 114253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Tie, J.; Hu, D. Regulation of SIRT1 and Its Roles in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 831168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhao, Y. SIRT1/PGC-1alpha Signaling Promotes Mitochondrial Functional Recovery and Reduces Apoptosis after Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Rats. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, D.; Wei, C.; Liu, L.; Xin, Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, R. The relationship between SIRT1 and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1465849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Kang, Y.J.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, H.C. SIRT1-dependent PGC-1alpha deacetylation by SRT1720 rescues progression of atherosclerosis by enhancing mitochondrial function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2024, 1869, 159453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.J.; Zhang, X.; Rodriguez-Velez, A.; Evans, T.D.; Razani, B. p62/SQSTM1 and Selective Autophagy in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 31, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Xing, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, F.; Sun, H. p62/SQSTM1, a Central but Unexploited Target: Advances in Its Physiological/Pathogenic Functions and Small Molecular Modulators. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 10135–10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lv, T.; Gu, X.; Feng, H.; Zhen, J.; Xin, W.; Wan, Q. SQSTM1/p62 Controls mtDNA Expression and Participates in Mitochondrial Energetic Adaption via MRPL12. iScience 2020, 23, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Fatahian, A.N.; Rouzbehani, O.M.T.; Hathaway, M.A.; Mosleh, T.; Vinod, V.; Vowles, S.; Stephens, S.L.; Chung, S.D.; Cao, I.D.; et al. Sequestosome 1 (p62) mitigates hypoxia-induced cardiac dysfunction by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Kaltwasser, B.; Pillath-Eilers, M.; Walkenfort, B.; Voortmann, S.; Mohamud Yusuf, A.; Hagemann, N.; Wang, C.; et al. Autophagy hub-protein p62 orchestrates oxidative, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and inflammatory responses post-ischemia, exacerbating stroke outcome. Redox Biol. 2025, 84, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.V.; Mills, J.; Lapierre, L.R. Selective Autophagy Receptor p62/SQSTM1, a Pivotal Player in Stress and Aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 793328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Gao, M.; Liu, B.; Qin, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Gong, G. Mitochondrial autophagy: Molecular mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, H.; Liu, J. P66Shc Deletion Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Cardiac Dysfunction in Pressure Overload-Induced Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, M.; Migliaccio, E.; Orsini, F.; Paolucci, D.; Moroni, M.; Contursi, C.; Pelliccia, G.; Luzi, L.; Minucci, S.; Marcaccio, M.; et al. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 2005, 122, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijhoff, J.; Dagnell, M.; Augsten, M.; Beltrami, E.; Giorgio, M.; Ostman, A. The mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulator p66Shc controls PDGF-induced signaling and migration through protein tyrosine phosphatase oxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 68, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, H.A.; Ali, R.; Mushtaq, U.; Khanday, F.A. Structure-functional implications of longevity protein p66Shc in health and disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 63, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Lin, L.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Ren, J. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology and mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; You, X.; Gao, B.; Sun, Y.; Liu, C. The Role of ROS in Atherosclerosis and ROS-Based Nanotherapeutics for Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerotic Lesion Targeting, ROS Scavenging, and ROS-Responsive Activity. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 22366–22381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: A perspective for the 1990s. Nature 1993, 362, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, S.E.; Robinson, A.J.B.; Zurke, Y.X.; Monaco, C. Therapeutic strategies targeting inflammation and immunity in atherosclerosis: How to proceed? Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tabas, I. Emerging roles of mitochondria ROS in atherosclerotic lesions: Causation or association? J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2014, 21, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batty, M.; Bennett, M.R.; Yu, E. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Cells 2022, 11, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendrov, A.E.; Lozhkin, A.; Hayami, T.; Levin, J.; Silveira Fernandes Chamon, J.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Runge, M.S.; Madamanchi, N.R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming induce macrophage pro-inflammatory phenotype switch and atherosclerosis progression in aging. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1410832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Y.; Wang, N.; Li, S.; Hong, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y. The Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophage Polarization: Reflecting Its Dual Role in Progression and Treatment of Human Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2795090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Deng, C.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Dai, B.; Guo, W.; Guo, Q.; Feng, Y.; Xu, H.; Song, X.; et al. A novel role for the ROS-ATM-Chk2 axis mediated metabolic and cell cycle reprogramming in the M1 macrophage polarization. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitinger, N.; Schulman, I.G. Phenotypic polarization of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.J.; Dragoljevic, D.; Tall, A.R. Cholesterol efflux pathways regulate myelopoiesis: A potential link to altered macrophage function in atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Ning, K.; Guo, H. M1/M2 macrophage-targeted nanotechnology and PROTAC for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Life Sci. 2024, 352, 122811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnewar, S.; Pulipaka, S.; Katta, S.; Panuganti, D.; Neeli, P.K.; Thennati, R.; Jerald, M.K.; Kotamraju, S. Mitochondria-targeted esculetin mitigates atherosclerosis in the setting of aging via the modulation of SIRT1-mediated vascular cell senescence and mitochondrial function in Apoe−/− mice. Atherosclerosis 2022, 356, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Liang, J.; Lu, Y.; Ding, J.; Peng, J.; Li, F.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wan, C.; et al. Lactoferrin influences atherosclerotic progression by modulating macrophagic AMPK/mTOR signaling-dependent autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A.J.; Ray, K.K.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Ditmarsch, M.; Kling, D.; Hsieh, A.; Szarek, M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Davidson, M.H. Impact of Obicetrapib on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in High-Risk Patients: A Pooled Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, M.; Barrett, T.J.; Fisher, E.A. HDL and Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. HPS2-THRIVE, AIM-HIGH and dal-OUTCOMES: HDL-cholesterol under attack. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2014, 2014, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, P.; Rohatgi, A. Niacin Therapy, HDL Cholesterol, and Cardiovascular Disease: Is the HDL Hypothesis Defunct? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2015, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingwell, B.A.; Nicholls, S.J.; Velkoska, E.; Didichenko, S.A.; Duffy, D.; Korjian, S.; Gibson, C.M. Antiatherosclerotic Effects of CSL112 Mediated by Enhanced Cholesterol Efflux Capacity. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.M.; Kazmi, S.H.A.; Korjian, S.; Chi, G.; Phillips, A.T.; Montazerin, S.M.; Duffy, D.; Zheng, B.; Heise, M.; Liss, C.; et al. CSL112 (Apolipoprotein A-I [Human]) Strongly Enhances Plasma Apoa-I and Cholesterol Efflux Capacity in Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients: A PK/PD Substudy of the AEGIS-I Trial. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 27, 10742484221121507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite-Moreira, A.M.; Lourenco, A.P.; Falcao-Pires, I.; Leite-Moreira, A.F. Pivotal role of microRNAs in cardiac physiology and heart failure. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, Y.K.; Bernardo, B.C.; Ooi, J.Y.; Weeks, K.L.; McMullen, J.R. Pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure: Signaling pathways and novel therapeutic targets. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1401–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, J.R.; Mongue-Din, H.; Eaton, P.; Shah, A.M. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.D.; Holody, C.D.; Wells, L.; Silver, H.L.; Morales-Llamas, D.Y.; Du, W.W.; Reeks, C.; Khairy, M.; Chen, H.; Ferdaoussi, M.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Modulator 1 Plays an Obligate Role in Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Tang, Q.F.; Wang, W. SLC26A4 regulates autophagy and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to mediate pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.B.; Zhao, S.T.; Xu, Z.Q.; Hu, L.J.; Zeng, R.Y.; Qiu, Z.C.; Peng, H.Z.; Zhou, L.F.; Cao, Y.P.; Wan, L. Thymoquinone mitigates cardiac hypertrophy by activating adaptive autophagy via the PPAR-gamma/14-3-3gamma pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 55, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Tong, T.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Y.; Shi, P.; Que, L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; et al. ECSIT-X4 is Required for Preventing Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy via Regulating Mitochondrial STAT3. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2414358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Cao, J.; Gu, J.; Zhu, X.; Qian, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W. SBK3 suppresses angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy by regulating mitochondrial metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakabe, A.; Zhai, P.; Ikeda, Y.; Saito, T.; Maejima, Y.; Hsu, C.P.; Nomura, M.; Egashira, K.; Levine, B.; Sadoshima, J. Drp1-Dependent Mitochondrial Autophagy Plays a Protective Role Against Pressure Overload-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Heart Failure. Circulation 2016, 133, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, D.P.; Amgalan, D.; Linkermann, A.; Liu, Q.; Kitsis, R.N. Fundamental Mechanisms of Regulated Cell Death and Implications for Heart Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1765–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Q.; Yang, W.; Zhu, X.; Feng, Z.; Song, J.; Xu, X.; Kong, M.; Mao, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, Y.; et al. Deptor protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating the mTOR signaling and autophagy. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusch, G. Myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and cardioprotection in perspective. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, L.; Tan, M.; Jin, Y.; Yin, Y.; Han, L.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, T.; et al. Corosolic acid attenuates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through the PHB2/PINK1/parkin/mitophagy pathway. iScience 2024, 27, 110448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Cao, C.; Xin, G.; Chen, Y.Y.; et al. Mitophagy in ischemic heart disease: Molecular mechanisms and clinical management. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.Y.; Vanhoutte, D.; Del Re, D.P.; Purcell, N.H.; Ling, H.; Banerjee, I.; Bossuyt, J.; Lang, R.A.; Zheng, Y.; Matkovich, S.J.; et al. RhoA protects the mouse heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3269–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ding, E.Y.; Yu, O.M.; Xiang, S.Y.; Tan-Sah, V.P.; Yung, B.S.; Hedgpeth, J.; Neubig, R.R.; Lau, L.F.; Brown, J.H.; et al. Induction of the matricellular protein CCN1 through RhoA and MRTF-A contributes to ischemic cardioprotection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 75, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Tan, V.P.; Yu, J.D.; Tripathi, R.; Bigham, Z.; Barlow, M.; Smith, J.M.; Brown, J.H.; Miyamoto, S. RhoA signaling increases mitophagy and protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia by stabilizing PINK1 protein and recruiting Parkin to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 2472–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Fu, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lao, Y.; Xu, H. Gerontoxanthone I and Macluraxanthone Induce Mitophagy and Attenuate Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. Melatonin Attenuates Anoxia/Reoxygenation Injury by Inhibiting Excessive Mitophagy Through the MT2/SIRT3/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway in H9c2 Cells. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2020, 14, 2047–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. Melatonin postconditioning ameliorates anoxia/reoxygenation injury by regulating mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics in a SIRT3-dependent manner. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 904, 174157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. SIRT3 and RORalpha are two prospective targets against mitophagy during simulated ischemia/reperfusion injury in H9c2 cells. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Yang, P.; Tao, J.; Lu, D.; Sun, L. ZNF143 regulates autophagic flux to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through Raptor. Cell. Signal. 2022, 99, 110444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yoon, N.; Dadson, K.; Sung, H.K.; Lei, Y.; Dang, T.Q.; Chung, W.Y.; Ahmed, S.; Abdul-Sater, A.A.; Wu, J.; et al. Impaired autophagy flux contributes to enhanced ischemia reperfusion injury in the diabetic heart. Autophagy Rep. 2024, 3, 2330327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Hu, X.; Lee, S.H.; Chen, F.; Jiang, K.; Tu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Du, J.; Wang, L.; Yin, C.; et al. Diabetes Exacerbates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Down-Regulation of MicroRNA and Up-Regulation of O-GlcNAcylation. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2018, 3, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, D. Research progress on the effects of novel hypoglycemic drugs in diabetes combined with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 86, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefer, D.J.; Granger, D.N. Oxidative stress and cardiac disease. Am. J. Med. 2000, 109, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Huang, S.; Wei, G.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Si, X.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. CircRNA Samd4 induces cardiac repair after myocardial infarction by blocking mitochondria-derived ROS output. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 3477–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, P.; Malik, A.; Chhabra, L. Heart Failure (Congestive Heart Failure). In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- D’Oria, R.; Schipani, R.; Leonardini, A.; Natalicchio, A.; Perrini, S.; Cignarelli, A.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Disease: From Physiological Response to Injury Factor. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5732956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Osko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczynska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress-A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.F.; Johnson, S.C.; Villarin, J.J.; Chin, M.T.; Nieves-Cintron, M.; Chen, T.; Marcinek, D.J.; Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Kang, Y.J.; Prolla, T.A.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and Galphaq overexpression-induced heart failure. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlidis, G.; Nascimben, L.; Couper, G.S.; Shekar, P.S.; del Monte, F.; Tian, R. Defective DNA replication impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in human failing hearts. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Tian, R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3716–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Jiang, X.; Perwaiz, I.; Yu, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huttemann, M.; Felder, R.A.; Sibley, D.R.; Polster, B.M.; et al. Dopamine D5 receptor-mediated decreases in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production are cAMP and autophagy dependent. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 44, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, X.; Long, A.; Feng, J.; Sun, S.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Jiang, X. An inducible mouse model of heart failure targeted to cardiac Drd5 deficiency detonating mitochondrial oxidative stress. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 396, 131560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Kong, B.; Shuai, W.; Zhang, J.J.; Huang, H. MD1 deletion exaggerates cardiomyocyte autophagy induced by heart failure with preserved ejection fraction through ROS/MAPK signalling pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 9300–9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, R.F.; Li, L.; Wang, A.L.; Yang, H.; Xi, J.; Zhu, Z.F.; Wang, K.; Li, B.; Yang, L.G.; Qin, F.Z.; et al. Enhanced oxidative stress mediates pathological autophagy and necroptosis in cardiac myocytes in pressure overload induced heart failure in rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielawska, M.; Warszynska, M.; Stefanska, M.; Blyszczuk, P. Autophagy in Heart Failure: Insights into Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Xiao, D.; Fang, X.; Wang, J. Oxidative modification of miR-30c promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation via CDKN2C mismatch. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Sha, X.; Huang, C.; Hu, L.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. Mitochondrial GSNOR Alleviates Cardiac Dysfunction via ANT1 Denitrosylation. Circ. Res. 2023, 133, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, M.; Sawa, T.; Kitajima, N.; Ono, K.; Inoue, H.; Ihara, H.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Suematsu, M.; Kurose, H.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide anion regulates redox signaling via electrophile sulfhydration. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, S.; Ago, T.; Kitazono, T.; Zablocki, D.; Sadoshima, J. The role of redox modulation of class II histone deacetylases in mediating pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 87, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Hill, M.A.; Sowers, J.R. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Mechanisms Contributing to This Clinical Entity. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 624–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.L.; Feng, Q.; Pan, S.; Fu, W.J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Early diagnostic biomarkers, pathogenetic mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Tan, X.; Liao, B.; Li, P.; Feng, J. Oxidative stress signaling in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy and the potential therapeutic role of antioxidant naringenin. Redox Rep. 2023, 28, 2246720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilkun, O.; Wilde, N.; Tuinei, J.; Pires, K.M.; Zhu, Y.; Bugger, H.; Soto, J.; Wayment, B.; Olsen, C.; Litwin, S.E.; et al. Antioxidant treatment normalizes mitochondrial energetics and myocardial insulin sensitivity independently of changes in systemic metabolic homeostasis in a mouse model of the metabolic syndrome. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 85, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Mijares, A.; Rocha, M.; Rovira-Llopis, S.; Banuls, C.; Bellod, L.; de Pablo, C.; Alvarez, A.; Roldan-Torres, I.; Sola-Izquierdo, E.; Victor, V.M. Human leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions and mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients and their association with silent myocardial ischemia. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firgany, A.A.M.A.-H.a.A.E.L. Favorable outcomes of metformin on coronary microvasculature in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Histol. 2018, 49, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qian, J.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Khan, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liang, G. Kaempferol attenuates hyperglycemia-induced cardiac injuries by inhibiting inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. Endocrine 2018, 60, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.S. A Synopsis of the Associations of Oxidative Stress, ROS, and Antioxidants with Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes induced by high glucose via upregulating AMPK activity. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. Naringenin ameliorates myocardial injury in STZ-induced diabetic mice by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis via regulating the Nrf2 and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 946766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribano-Lopez, I.; Diaz-Morales, N.; Rovira-Llopis, S.; de Maranon, A.M.; Orden, S.; Alvarez, A.; Banuls, C.; Rocha, M.; Murphy, M.P.; Hernandez-Mijares, A.; et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ modulates oxidative stress, inflammation and leukocyte-endothelium interactions in leukocytes isolated from type 2 diabetic patients. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Shen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Pan, R.; Kuang, S.; Liu, G.; Sun, G.; Sun, X. Myricitrin Alleviates Oxidative Stress-induced Inflammation and Apoptosis and Protects Mice against Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Ge, X.; Meng, L.; Kong, J.; Meng, X. Regulatory T cells protect against diabetic cardiomyopathy in db/db mice. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The HOPE (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation) Study: The design of a large, simple randomized trial of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril) and vitamin E in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events. The HOPE study investigators. Can. J. Cardiol. 1996, 12, 127–137.

- Lonn, E.; Bosch, J.; Yusuf, S.; Sheridan, P.; Pogue, J.; Arnold, J.M.; Ross, C.; Arnold, A.; Sleight, P.; Probstfield, J.; et al. Effects of long-term vitamin E supplementation on cardiovascular events and cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005, 293, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioli, R.; Schweiger, C.; Tavazzi, L.; Valagussa, F. Efficacy of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: Results of GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico. Lipids 2001, 36, S119–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Porteous, C.M.; Gane, A.M.; Murphy, M.P. Delivery of bioactive molecules to mitochondria in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5407–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Rivero, J.M.; Pastor-Maldonado, C.J.; de la Mata, M.; Villanueva-Paz, M.; Povea-Cabello, S.; Alvarez-Cordoba, M.; Villalon-Garcia, I.; Suarez-Carrillo, A.; Talaveron-Rey, M.; Munuera, M.; et al. Atherosclerosis and Coenzyme Q10. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Battson, M.L.; Cuevas, L.M.; Eng, J.S.; Murphy, M.P.; Seals, D.R. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapy with MitoQ ameliorates aortic stiffening in old mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 124, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossman, M.J.; Santos-Parker, J.R.; Steward, C.A.C.; Bispham, N.Z.; Cuevas, L.M.; Rosenberg, H.L.; Woodward, K.A.; Chonchol, M.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; et al. Chronic Supplementation With a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Function in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.P.; Wrolstad, D.; Bakris, G.L.; Chertow, G.M.; de Zeeuw, D.; Goldsberry, A.; Linde, P.G.; McCullough, P.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Wittes, J.; et al. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Maulik, N.; Engelman, R.M.; Ho, Y.S.; Das, D.K. Targeted disruption of the mouse Sod I gene makes the hearts vulnerable to ischemic reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]