1. Introduction

Cells must continuously adapt to fluctuating environmental and intracellular conditions, a process fundamentally governed by the regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level [

1]. Transcription factors and repressors orchestrate this adaptive response by binding to specific DNA sequences and modulating the recruitment of the transcriptional machinery, thereby activating or silencing gene expression as needed. This dynamic interplay is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, enabling responses to stress, and preventing pathological states. An important class of transcription factors involved in these processes is the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family, characterised by a conserved basic region for DNA binding and a leucine zipper motif that mediates dimerization. The modularity of bZIP proteins allows them to form both homo- and heterodimers, greatly expanding their DNA-binding specificity and regulatory potential [

2]. Among the bZIP superfamily, the Cap ‘n’ Collar (CNC) subfamily—including NRF2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2), BACH1 (broad complex, tramtrack, and bric-a-brac (BTB) and CNC homology 1), and small Maf proteins (sMafs, e.g., sMafF, sMafG, and sMafK)—plays a pivotal role in the transcriptional regulation of stress-responsive genes.

One of the most critical challenges for aerobic cells is the maintenance of redox balance. Reactive oxygen species, produced as byproducts of metabolism or in response to external insults, can cause significant cellular damage at elevated levels. To counteract oxidative stress, cells rely on a robust network of antioxidant defence genes, many of which are regulated by the NRF2 pathway [

3]. Under basal conditions, NRF2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by Keap1 (kelch-like enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase (ECH)-associated protein 1), which targets it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Upon oxidative or electrophilic stress, modifications of Keap1 cysteine residues disrupt the ubiquitination reaction [

4]. This allows the newly synthesised NRF2 molecules to accumulate and translocate into the nucleus [

5]. In the nucleus, NRF2 heterodimerises with sMaf proteins and binds to CNC-sMaf-binding element (CsMBE) [

6] in the promoters of target genes. Among these, antioxidant response elements (AREs) represent a functionally important subset that drives the expression of genes involved in a broad cytoprotective programme.

Importantly, the CsMBEs are occupied by repressive complexes in the absence of stimulation. In fact, sMaf proteins act as repressors when forming homodimers because they lack transactivation domains. BACH1 can also form heterodimers with sMaf to bind CsMBEs in the promoter regions of iron metabolism genes (e.g., heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), ferritin heavy chain 1, and ferritin light chain). These genes are uniquely regulated by hemes, which inhibit the DNA-binding ability of BACH1 [

7,

8] and promote its degradation [

9,

10]. This provides a rapid mechanism for gene derepression during cellular oxidative and heme stress. In keratinocytes, BACH1 knockdown was found to cause the robust derepression of HMOX1 and more modest increases in other NRF2 target genes (e.g., glutathione synthesis). This suggests that while KEAP1–NRF2 signalling is the dominant regulator of the antioxidant response, BACH1 could provide an additional layer of gene-specific repression [

11]. Importantly, a possible second layer of redox regulation has been reported in NRF2 and BACH1. These proteins contain a conserved cysteine residue located near the DNA phosphate backbone that could act as a redox sensor. The C574S mutation in BACH1 abolishes its sensitivity to diamide, leading to persistent transcriptional repression even under oxidative conditions [

12]. In contrast, the C506S mutation in mouse NRF2 (corresponding to Cys514 in humans) renders the transcription factor unable to activate gene expression in response to oxidative stress, likely due to the impaired DNA binding [

13]. Together, these findings suggest that both transcriptional repressors and activators of CsMBE-driven genes are regulated by redox-sensitive mechanisms targeting their DNA-binding domains.

While NRF2 activation provides cytoprotection and suppresses carcinogenesis under physiological conditions, persistent NRF2 stabilisation—frequently due to mutations in Keap1 or NRF2—promotes tumour survival, metabolic adaptation, and chemoresistance [

14]. BACH1, a transcriptional repressor, is recognised for its ability to drive tumour metastasis by repressing antioxidant genes and fostering pro-metastatic programmes [

15]. Notably, recent work demonstrates that sustained NRF2 activation can stabilise BACH1 by inducing HO-1, thereby inhibiting BACH1 degradation and enhancing the metastatic potential, particularly in lung [

16] and pancreatic cancers [

17]. The elevated expression of both BACH1 and NRF2 correlates with a poor prognosis, emphasising the importance of their interplay at CsMBE promoters in cancer biology and therapy.

The structural basis for a DNA-bound sMafG homodimer [

18] and DNA-bound NRF2/sMafG heterodimer [

19] has been elucidated by crystallography. Both sMafG/sMafG and NRF2/sMafG utilise their leucine zippers to homo- and heterodimerise, whilst the basic regions of each monomer interact with the major groove of the CsMBE. These CNC-bZIP proteins share a similar overall architecture, with the CNC domain contributing to DNA-binding specificity and protein–protein interactions and the bZIP domain mediating dimerisation and DNA binding. Notably, bZIP proteins can form both homo- and heterodimers, and both sMafG and NRF2 have been shown to bind DNA as homodimers in vitro [

19].

Previous studies have shown how NRF2 can outcompete the sMafG/sMafG homodimer to form an active NRF2/sMafG heterodimer, representing the activation of the promoters. However, to our knowledge, NRF2 outcompeting BACH1 has not been demonstrated in a reconstituted system mimicking the activation of iron metabolism genes. On the other hand, the re-inactivation of these genes (BACH1 replacing NRF2) has not been investigated. The roles of the oxidative modifications of cysteines in the DNA-binding domains of BACH1 remains to be fully elucidated with regard to the heme-sensing capabilities of BACH1. To address these gaps, we have adapted a tethering approach with a cleavable linker and fluorescent tagging to dissect the molecular mechanisms underlying the transition between repressed (BACH1/sMafG) and activated (NRF2/sMafG) states, as well as the re-inactivation process (NRF2/sMafG to BACH1/sMafG). Using competition assays, we observe that the displacement of the bZIP factors is facilitated when they compete as heterodimers instead of homodimers. In addition, the tethering system preserves the redox regulation of BACH1 through C574 oxidation, allowing us to probe how this post-translational modification influences BACH1’s DNA binding and promoter occupancy. We propose that the oxidation of BACH1 C574 acts as a secondary safety mechanism, preventing BACH1 from binding to CsMBE ARE promoters under oxidative conditions and ensuring the appropriate activation of antioxidant gene expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning and Mutagenesis

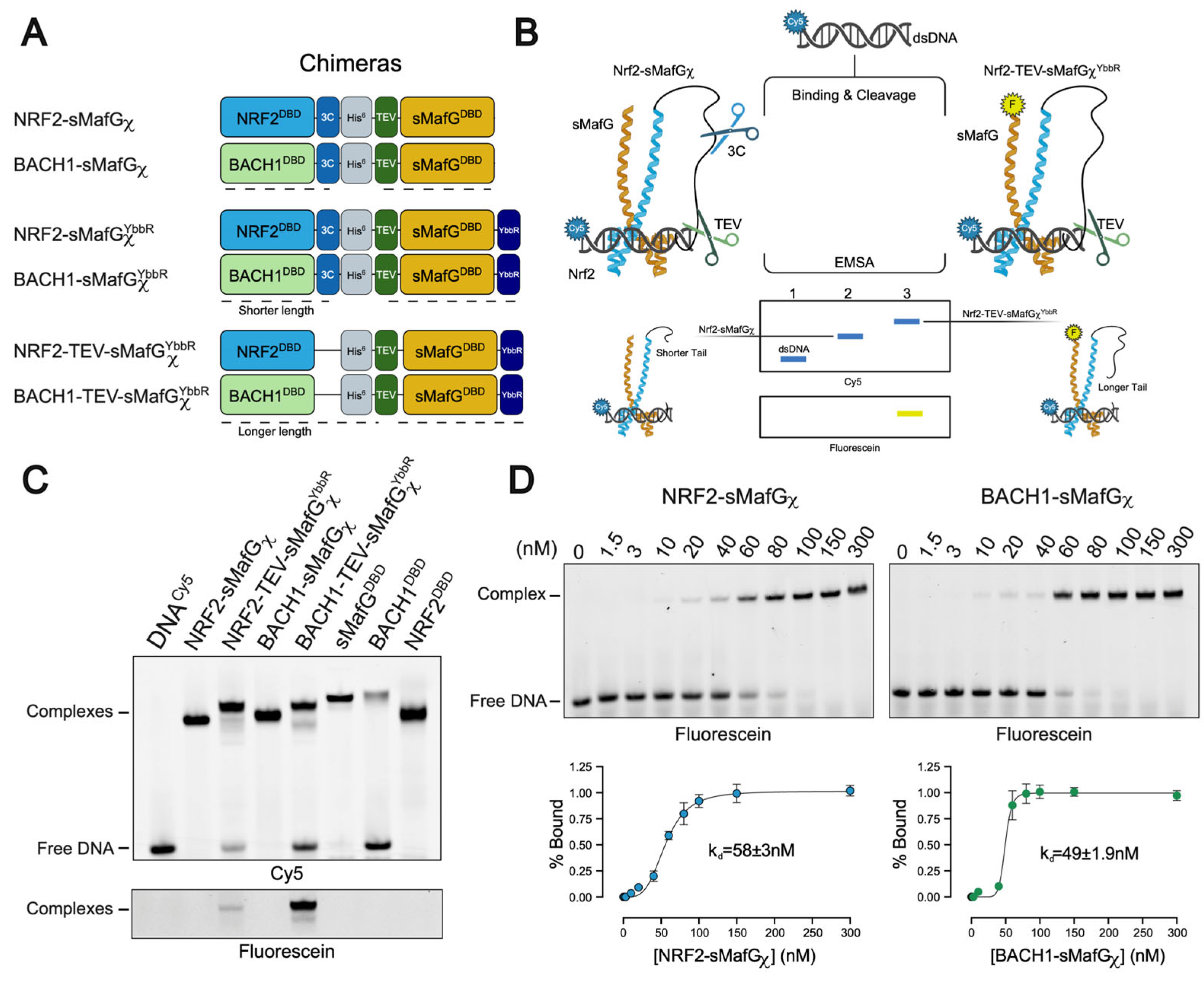

Synthetic genes for full length BACH1, sMafG, and NRF2 have been codon-optimised and purchased from Genscript. The DNA-binding domains were subcloned in pET29 (BACH1residues 511–627, sMafG residues 1–162, and NRF2 residues 451–567) with a cleavable His-tag to yield the following constructs: BACH1DBD-3C-6xHis-pET29, 6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBD-pET29, and NRF2DBD-3C-6xHis-pET29.

Chimeric constructs were synthesised by fusing NRF2DBD or BACH1DBD with sMafGDBD gene to obtain NRF2-sMafGχ (NRF2DBD-3C-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-pET29) and BACH1-sMafGχ (BACH1DBD-3C-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-pET29), respectively. The sequence of the linker is as follows: GSGLEVLFQGPGSAGSAAGSGEGSAGHHHHHHGSAGSAAGSGHHHHHHGSASAAGSGESAGASEGSGAASGASGEGSAGSENLYFQGG. Point mutation of BACH1C574A-sMafGχ was generated by divergent PCR.

YbbR containing chimeric constructs were generated by introducing a YbbR tag (DSLEFIASKLA) to the C-terminus of the NRF2-sMafGχ and Bach1-sMafGχ constructs using divergent PCR. The generated constructs are NRF2-sMafGχYbbR (NRF2DBD-3C-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-YbbR-pET29) and BACH1-sMafGχYbbR (BACH1DBD-3C-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-YbbR-pET29). To observe different gel shifts during competition assays, we generated NRF2DBD-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-YbbR-pET29 and BACH1DBD-6xHis-TEV-sMafGDBDχ-YbbR-pET29 constructs by removing the 3C protease cleavage site using divergent PCR.

2.2. Protein Expression and Purification of the DNA-Binding Domain and Chimeric Constructs

The DBD constructs were expressed at 30 °C for 3 h 30 min in E. coli One Shot™ BL21 Star™ cells (DE3; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) using 1 mM IPTG when the optical density (OD600) reached 0.7. The chimeric constructs were expressed overnight (O/N) at 20 °C with 1 mM IPTG supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. After expression, the cells were harvested by centrifugation using a Beckman Coulter JLA8.1000 rotor (5000 rpm; Amersham, UK) for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in the resuspension buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MgCl2, 40 mU/mL DNaseI-XT (NEB), and 5 mM imidazole and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany)). After resuspension, cells were sonicated using Soniprep 150 (5 s pulse ON/5s pulse OFF; 10 min at 35% amplitude). Following sonication, the sample was centrifuged using the Beckman CoulterJA-25.50 rotor (18,000 rpm) for 30 min at 4 °C.

Protein purification was performed using the ÄKTA Pure™ system (Cytiva, Amersham, UK). The filtered lysate was loaded onto a HisTrap™ HP column (Cytiva) equilibrated in binding buffer (50 mM HEPES 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM imidazole). The column was washed with 50 mM HEPES 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 50 mM imidazole. Proteins were eluted with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 300 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was then diluted to have a lower NaCl concentration and loaded onto a HiTrap™ Heparin HP (Cytiva) column, equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT, and 250 mM NaCl. The protein was eluted using a step elution with 1 M NaCl in the same buffer. The eluted protein was further purified using size exclusion chromatography. The protein was injected in Superdex™ 200 Increase 16/600 column (Cytiva), equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 2 mM TCEP, and 500 mM NaCl. The purity of the sample was assessed using SDS-PAGE gel. The protein concentration was determined using the Pierce™ Bradford plus protein assay reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and the protein was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C. All the proteins were expressed and purified similarly, except for NRF2DBD, which was purified by His-tag purification followed by Heparin purification.

2.3. Protein Expression and Purification of TEV, 3C, and Sfp

Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease, HRV 3C (3C) protease, and 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (Sfp) were expressed overnight at 20 °C with 1 mM IPTG in E. coli One Shot™ BL21 Star™ cells (DE3; Invitrogen). These constructs have been gifted by Alessandro Vannini. After expression, cells were harvested and sonicated as described above, excluding the use of protease inhibitors within the lysis buffers. Protein purification was performed using the ÄKTA Pure™ system (Cytiva).

The 3C lysate was loaded onto a HisTrap™ HP column (Cytiva) equilibrated in binding buffer (25 mM HEPES 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM imidazole). The column was washed with 15% elution buffer, followed by a step elution with 100% elution buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 300 mM imidazole). The eluted protein was diluted to lower the NaCl concertation. The protein was then loaded onto HiTrap™ SP HP column (Cytiva) equilibrated in 8% elution buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 160 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT), followed by a gradient elution to 50% elution buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). The purity of the purified sample was assessed using SDS-PAGE gel. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay reagent and the protein was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C. The TEV lysate was passed onto a HisTrap™ HP column (Cytiva) equilibrated in binding buffer (25 mM HEPES 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM imidazole). The column was washed with 15% elution buffer, followed by a step elution with 100% elution buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, and 300 mM imidazole). Sfp (phosphopantetheinyl transferase) was purified as described previously [

18].

2.4. SEC-MALS Analysis of Protein Oligomeric State

To assess the oligomeric state of BACH1DBD and sMafGDBD, we performed size exclusion chromatography coupled with multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS; Agilent 1100, Wyatt Dawn8+, T-rEX; Cheadle, UK). The Superdex™ 75 increase 10/300 column (Cytiva) was equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 2 mM TCEP, and 500 mM NaCl. The protein (1–2 mg) was injected into the system, and the chromatograms obtained were exported and analysed by GraphPad Prism (version 10).

2.5. CoA–Fluorescein Conjugation and Protein Labelling

The CoA–fluorescein conjugate was generated as described before [

20]. Briefly, fluorescein-5-maleimide (; 1.2 mg in 500 μL DMSO, Thermo Fisher) and coenzyme A (CoA) trilithium salt (BIC7401; Apollo Scientific, Manchester, UK; and 3.2 mg in 1500 μL 100 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0 mM) were incubated at 25 °C for 1 h in the dark. HPLC (Waters, Elstree, UK) was used to purify the CoA–fluorescein conjugate. The sample was centrifuged to remove precipitants and injected onto a 10 × 250 mm C8 Vydac column (Cat. 208TP1010) equilibrated by 2.5% acetonitrile in 200 mM ammonium acetate pH 6. The CoA–fluorescein conjugate was eluted using isocratic elution (200 mM ammonium acetate pH 6 and 2.5% acetonitrile) from time 0–2 min, followed by gradient elution (2.5–32.5% acetonitrile in 200 mM ammonium acetate pH 6) from time 2–17 min at 6 mL/min flow rate. The CoA–fluorescein conjugate peak was detected at 215 nm and 260 nm. The eluted peak (at 11.2 min) was then lyophilized and stored at −20 °C. Prior to protein labelling, the lyophilized CoA–fluorescein conjugate was resuspended in water, and its concentration was measured using the Nanodrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher).

To label the YbbR tag containing constructs (NRF2-sMafGχYbbR, BACH1-sMafGχYbbR, NRF2-TEV-sMafGχYbbR, and BACH1-TEV-sMafGχYbbR) with fluorescein, a 1:2:0.2 ratio of protein (1 mg)/CoA–fluorescein conjugate/Sfp was used. The mixture was incubated for 2 h at 25 °C in the dark. To separate the labelled protein Sfp, the sample was diluted with a low NaCl-containing buffer and then applied onto a HiTrap™ Heparin column (1 mL, Cytiva), equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, and 250 mM NaCl. The protein was eluted using a gradient elution of 0–75% elution buffer (100% elution buffer: 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, and 2 M NaCl) for 20 min. Both 280 nm and 488 nm were monitored. The purity of the sample was assessed using SDS-PAGE gel. The protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay and nanodrop. The labelled proteins were stored at −80 °C.

2.6. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

EMSAs were used to study the protein–DNA interactions. A 30-mer sequence of fluorescently labelled Forward (5′-[Fluo]-ctcgggaccgTGACTCAGCAggaaaaacac-3′) and a non-labelled Reverse oligonucleotide (5′gtgtttttccTGCTGAGTCAcggtcccgag-3′) were synthesised by Sigma (Merck Life Science, Gillingham, UK). This sequence, including the flanking regions, is based on naturally occurring CsMBE found in the HMOX-1 promoter (GRCh37/hg19 chr22:35,768,001–35,768,031 or GRCh38/hg38 chr22:35,372,008–35,372,037) and known to be bound by BACH1 [

21] and NRF2 [

22] in ChIP-seq. The fluorophore on the Fw oligo is either fluorescein or Cy5, as indicated for each experiment. The oligos were annealed using the Biorad thermal cycler (Watford, UK).

To determine the affinity constants (Kd) of the chimeric constructs (NRF2-sMafGχ and BACH1-sMafGχ), increasing concentrations of the proteins (0–300 nM) were mixed with the fluorescein labelled dsDNA (3 nM) in the reaction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM DTT, and 2 mM MgCl2). The samples were incubated with TEV (50 μg/mL) and 3C (50 μg/mL) proteases for 4 h at 25 °C and then loaded on a 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. A similar experimental setup was used to determine the relative Kd of NRF2DBD, BACH1DBD, and sMafGDBD (0–3 μM). Independent triplicates were performed for each experiment.

To compare the migration of the different chimeric constructs (NRF2-sMafGχ, NRF2-TEV-sMafGYbbR, BACH1-sMafGχ, and BACH1-TEV-sMafGYbbR), the proteins were incubated with Cy5-labelled dsDNA (3 nM) and TEV (50 μg/mL) and 3C (50 μg/mL) proteases for 4 h at 25 °C. As a control, the DBD-containing proteins (NRF2DBD, BACH1DBD, and sMafGDBD) were also used. The samples were then loaded on a 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Independent duplicates were performed.

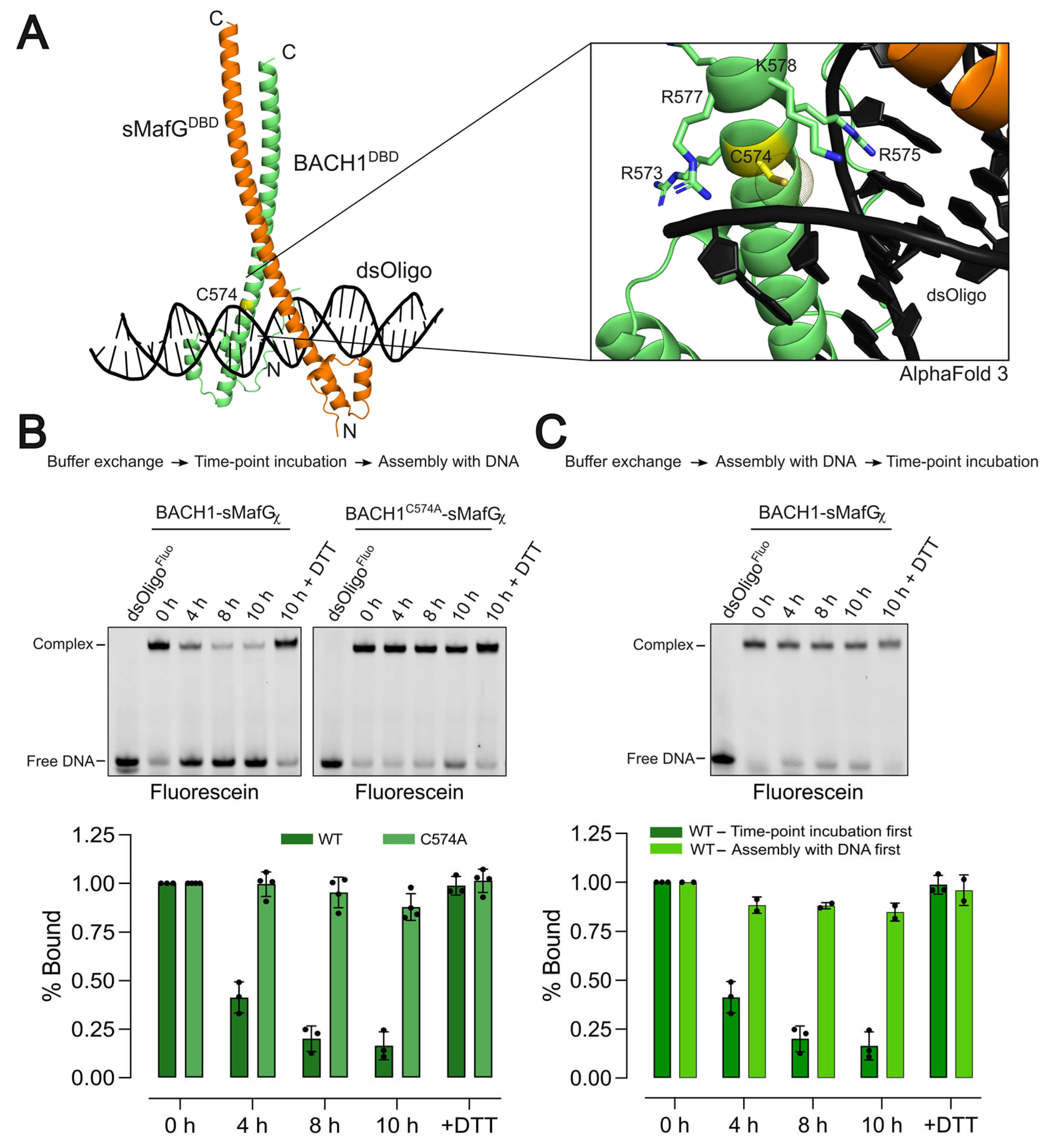

2.7. Time-Course Experiment on C574 Redox Sensitivity

Prior to the time-course protein oxidation experiment, the reducing agent was removed from the sample by gel filtration (Superdex™ 200 increase 5/150 column, Cytiva) using a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, and 500 mM NaCl. The eluted sample was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Two experimental setups were used. In the “incubation-first experiment”, BACH1-sMafGχ or BACH1C574A-sMafGχ (200 nM) was incubated under non-reducing conditions (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM MgCl2) at 4 °C for 0, 4, 8, or 10 h. Proteins were then mixed with fluorescein-labelled dsDNA (3 nM) and TEV/3C proteases (50 μg/mL each) and incubated for 4 h at 25 °C. A parallel 10 h sample was supplemented with 5 mM DTT.

In the “assembly-first experiment”, BACH1-sMafGχ (200 nM) was first assembled with fluorescein-labelled dsDNA (3 nM) and TEV/3C proteases (50 μg/mL each), followed by incubation at 4 °C for 0, 4, 8, or 10 h. A 10 h sample with 5 mM DTT was included as control. All samples were analysed on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Incubation-first assays were performed in ≥3 independent replicates, and assembly first assays in two replicates.

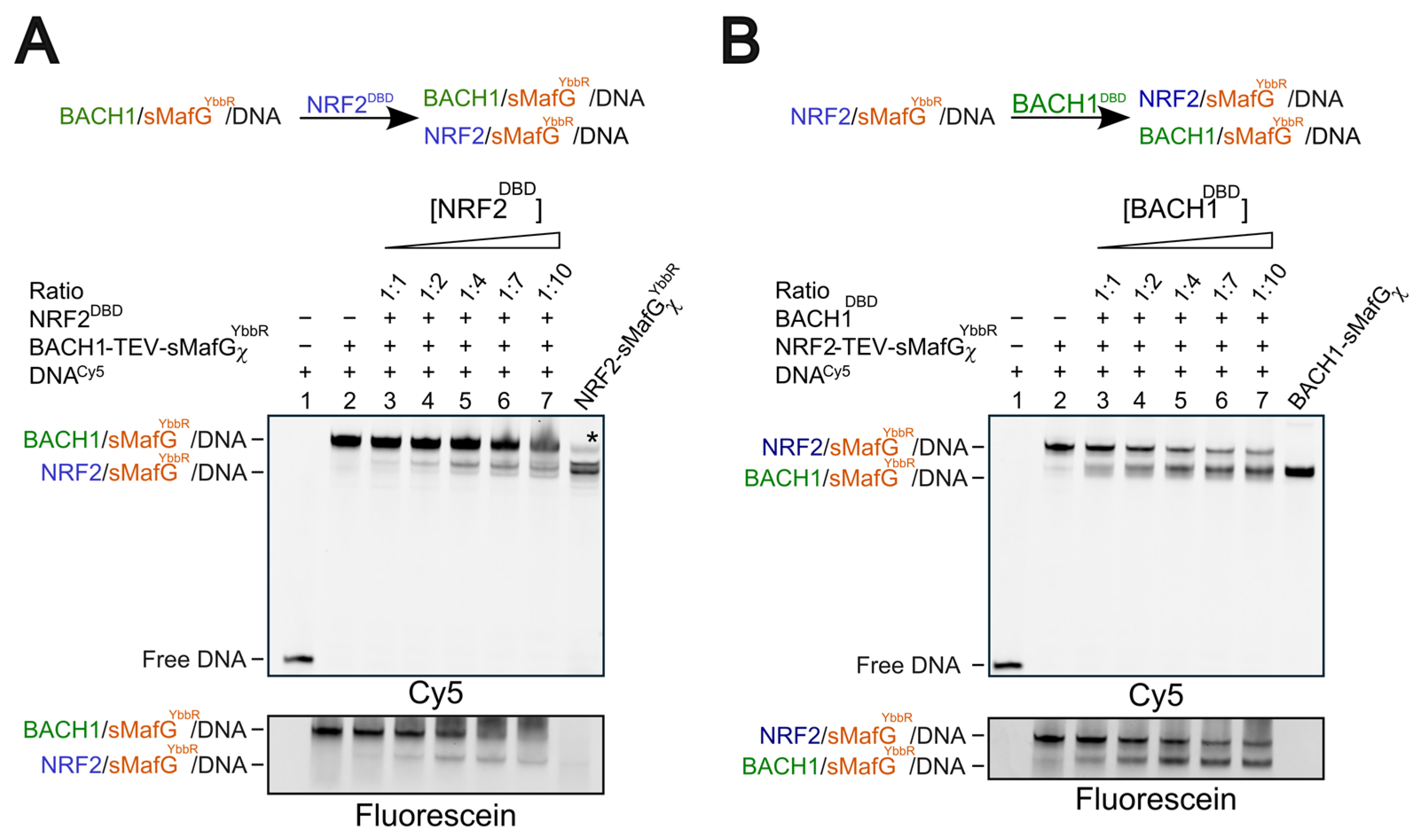

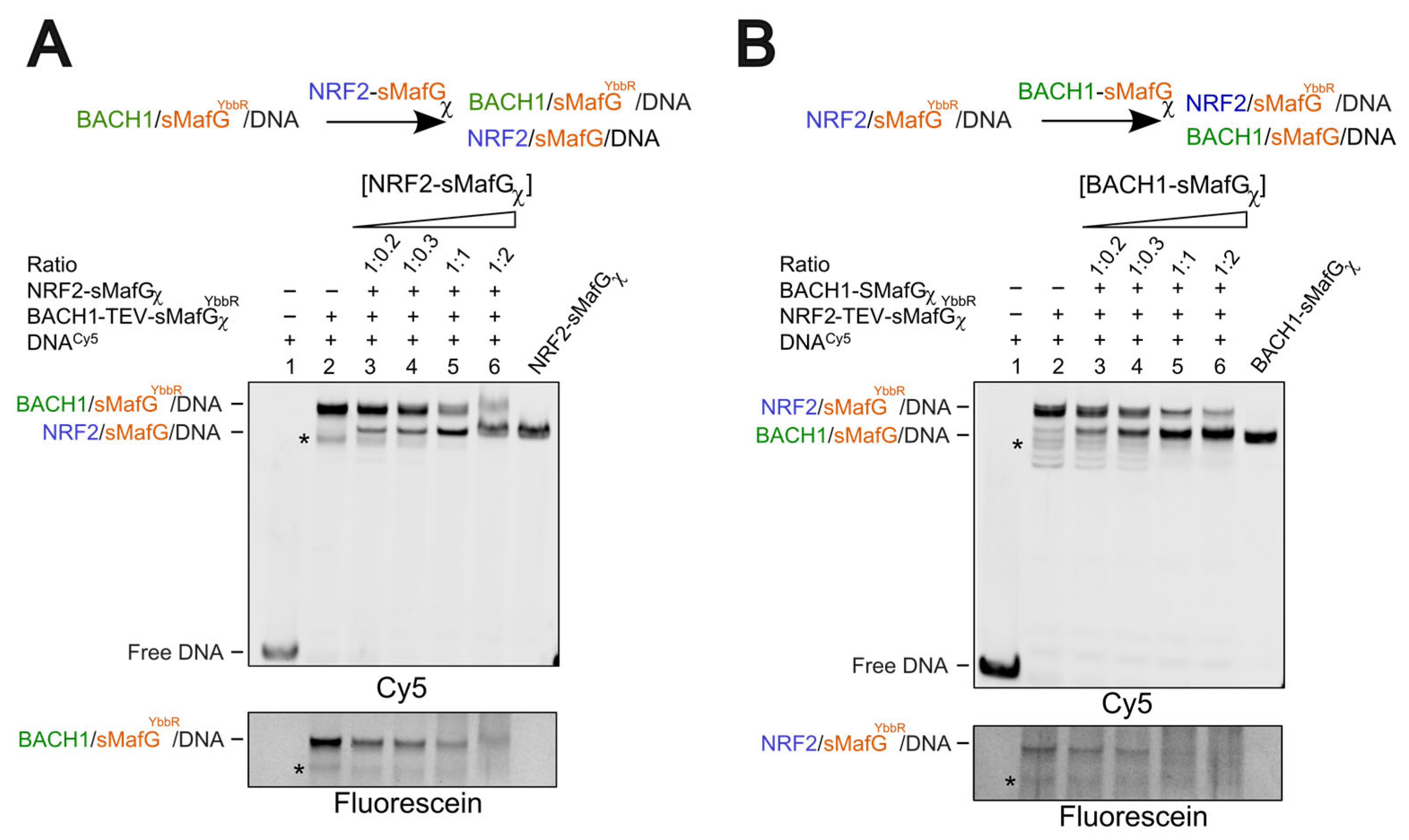

2.8. Competition Assays Using EMSA

To perform competition assays, fluorescein-labelled NRF2-TEV-sMafGχYbbR (150 nM) was incubated with Cy5-labelled dsDNA (3 nM) and TEV (50 μg/mL) and 3C (50 μg/mL) proteases for 4 h at 25 °C. Following the incubation, increasing concentrations of BACH1DBD (150 nM-1.5 μM) or BACH1-sMafGχ (25–300 nM) were added, and the samples were incubated O/N at 4 °C. Similarly, fluorescein-labelled BACH1-TEV-sMafGχYbbR (150 nM) was incubated with Cy5-labelled dsDNA and TEV/3C proteases for 4 h at 25 °C. Following the incubation, increasing concentrations of NRF2DBD (150 nM–1.5 μM) or NRF2-sMafGχ (25–300 nM) were added, and the samples were incubated O/N at 4 °C. For the titration by DBD proteins, either NRF2-sMafGχYbbR or BACH1-sMafGχ were used as controls. For the titration by chimeric constructs, NRF2-sMafGχ or BACH1-sMafGχ were used as controls in the absence of the fluorescein-labelled proteins. All the samples were then loaded on a 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Independent duplicates were performed for each experiment.

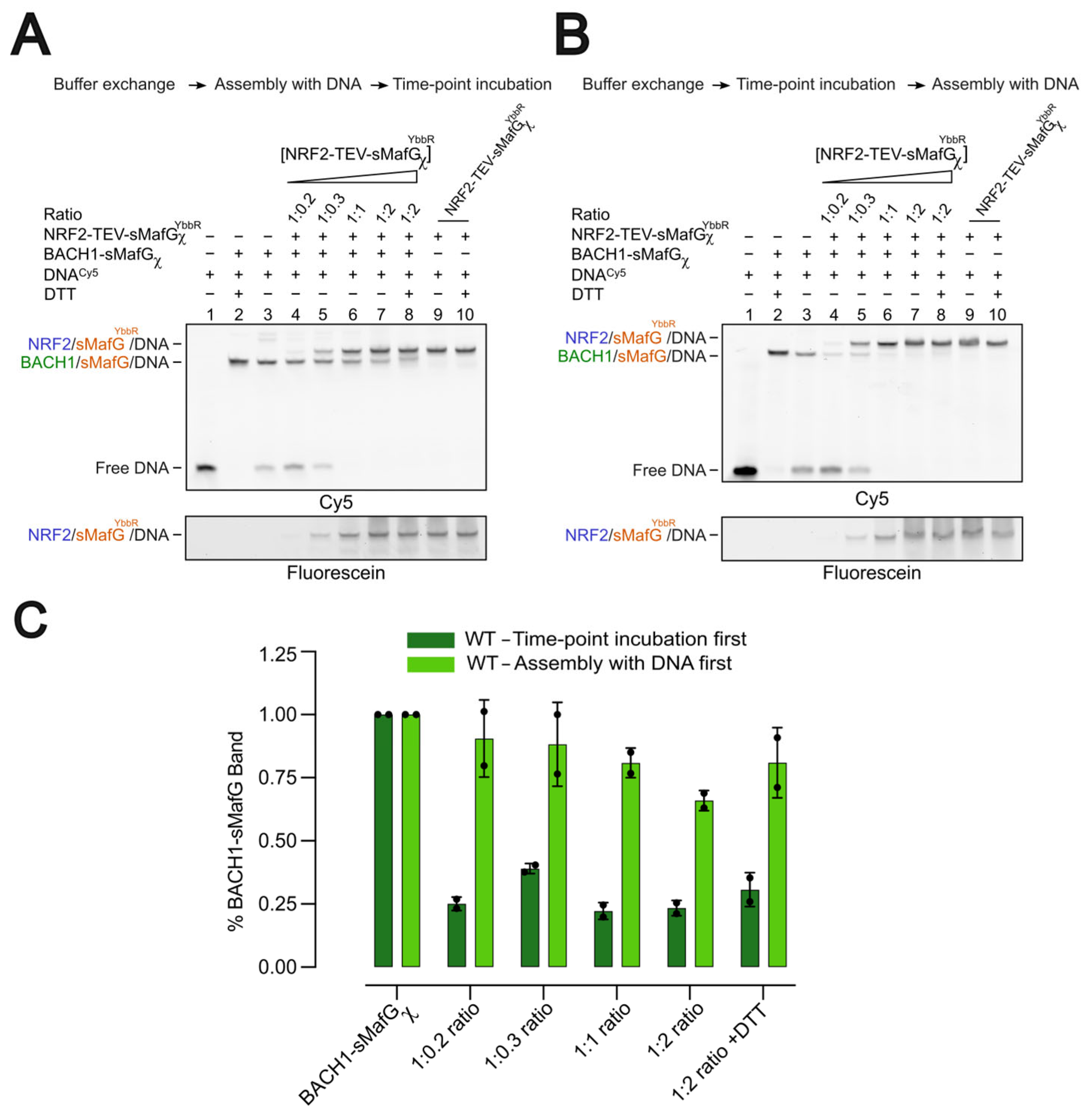

2.9. BACH1/sMafG Displacement by NRF2/sMafG Under Non-Reducing Conditions

Bach1/sMafG was buffer exchanged as described above. In the “assembly-first experiment”, BACH1-sMafGχ (200 nM) was preassembled with Cy5-labelled dsDNA (3 nM; in presence of TEV/3C) and then incubated at 4 °C for 8 h under non-reducing conditions. In the “incubation-first experiment”, BACH1-sMafGχ (200 nM) was incubated at 4 °C for 8 h under non-reducing conditions and then assembled with Cy5-labelled dsDNA (3 nM; in presence of TEV/3C) for 4 h at RT. For both experiments, the BACH1/sMafG/dsDNA complex was incubated O/N with increasing concentrations of fluorescein-labelled NRF2-TEV-sMafGYbbR at 4 °C. All the samples were then loaded on a 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. At least two independent replicates were performed for each experiment.

2.10. EMSA Running, Scanning, and Processing

The EMSAs with 6% and 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels were ran in 1X TBE buffer at 4 °C, 40 mA for 17 min or 30 min, respectively. The gels were imaged by the Amersham Typhoon 5 (Cytiva) using the Cy5 670BP30 and Cy2 525BP20 filters, which detect the Cy5 and fluorescein signals, respectively. Band intensity quantification was performed by ImageQuant™ analysis software (version 11.0; Cytiva). To determine the K

d values, the protein concentration in function of %Protein bound to DNA was plotted using GraphPad Prism10. The curve was fitted to a non-linear regression, and the K

d value was obtained. Bands marked with an asterisk correspond to degradation products (figure in the

Section 3.5), incomplete linker cleavage (figure in

Section 3.4), non-specific species, or combination of these (

Figure S3).

2.11. BACH1/sMafG/CsMBE Structure Prediction

Protein structures were predicted using AlphaFold 3 server [

23]. Sequences of the DNA-binding domains (BACH1 residues 511–627, sMafG residues 1–162) as well as CsMBE-containing sequences (5′-ctcgggaccgTGACTCAGCAggaaaaacac-3′ and 5′-gtgtttttccTGCTGAGTCAcggtcccgag-3′) were used as inputs. Predicted structures were assessed using pLDDT (most of the structure reached >90, especially around C574), ipTM (0.78, suggesting that the predicted structure is close to experimental ones), and PAE (shows very low expected error around C574).

2.12. Sequence Alignments

Sequences were retrieved from Uniprotkb with the following identifiers: Q16236 (NF2L2_HUMAN, human NRF2), O15525 (MAFG_HUMAN, human sMafG), 14867 (BACH1_HUMAN, human BACH1), P97302 (BACH1_MOUSE, mouse BACH1), A0A4X1U9G6 (A0A4X1U9G6_PIG, pig BACH1), F7BYY6 (F7BYY6_XENTR, xenopus BACH1), and A0AB32T1F9 (A0AB32T1F9_DANRE, zebrafish BACH1). Sequences were aligned using Clustal omega (version 1.2.4) [

24]; the alignments were prepared using ESPript (version 3.0) [

25].

2.13. Crosslinking Using Hanging-Drop Vapour Diffusion Method

To determine the oligomerization states of BACH1

DBD and sMafG

DBD, the proteins were crosslinked by glutaraldehyde using the hanging-drop vapour diffusion method [

26]. Briefly, 120 μL at 5% for BACH1

DBD or 25% for sMafG

DBD was added into the wells of a 48-well crystallisation plate, and 5–7 μM of protein (10 μL) was added onto a cover slip. Wells were covered by the cover slip, and the sample was incubated for 15 min (sMafG

DBD) or 45 min (BACH1

DBD) to allow for vapour diffusion and protein crosslinking. Following incubation, 250 mM ammonium sulfate was added to stop the crosslinking reaction. The sample was then mixed with SDS-loading dye, boiled, and analysed on SDS-PAGE using Coomassie staining (Instant Blue; Expedeon Ltd., Swavesey, UK).

4. Discussion

In this study, we employed a chimeric tethering strategy combined with covalent fluorescent labelling to dissect the DNA-binding dynamics and competitive interplay between repressive BACH1/sMafG and activating NRF2/sMafG heterodimers. By covalently linking the DNA-binding domains of BACH1

DBD and NRF2

DBD to sMafG

DBD using a protease-cleavable linker, we enforced heterodimer formation and overcame the kinetic limitations associated with partner exchange in vitro. This experimental design allowed us to quantitatively assess DNA-binding affinities, redox sensitivity, and the displacement behaviour of various bZIP dimers at CsMBEs. Importantly, the sequence chosen as well as the flanking regions are found to be bound by both BACH1 and NRF2 in ChIP-seq experiments [

21,

22]. Therefore, our results are likely to be generalisable to other all CsMBE sequences.

Our results demonstrate that both tethered NRF2/sMafG and BACH1/sMafG heterodimers bind CsMBE sequences with a high affinity, surpassing those of their respective bZIP homodimers. This finding validates the utility of our approach for dissecting stable heterodimer/DNA interactions. A similar tethering method has previously been applied to study sMafG/NRF2 in cells [

30]; here, we extend their applicability to BACH1/sMafG. The inclusion of fluorescently labelled sMafG

YbbR enabled the tracking of partner replacements in EMSA, offering a precise readout for the dynamics of heterodimer exchange. This modular and broadly applicable system could be adapted to other bZIP pairings, providing a powerful means to investigate DNA-binding competition and exchange under defined and tuneable biochemical conditions.

Our data show that, like sMafG

DBD, BACH1

DBD can form homodimers in a solution in the absence of DNA. This dimerisation is likely an artefact of recombinant expression: the leucine zipper presents an apolar surface that promotes dimer formation, with surrounding residues further contributing to the interaction [

28]. In contrast, NRF2

DBD showed no evidence of dimerisation under the same conditions, likely due to its predominantly disordered nature [

34]. Consistently, the NMR structure of a construct comprising only the CNC and basic regions (

Figure S1A) shows that the CNC domain is folded, while the basic region is disordered (PDB ID 2LZ1).

In the cellular context, there is compelling evidence that NRF2 associates with sMafG in the nucleoplasm, even in absence of DNA binding. A study by Li et al. showed that the leucine zipper of NRF2 can associate with sMafG in cells, enhancing the nuclear retention of NRF2 by masking its NESzip motif [

35]. This suggests that NRF2/sMafG heterodimerisation plays a role in the subcellular localisation independent of DNA binding. While earlier in vitro biochemical data demonstrated that BACH1 binds sMafG in the presence of DNA [

7], cellular interaction off the DNA should be assessed in the future. Consistent with the idea that NRF2 (and possibly BACH1) associate with sMafG off the DNA in cells, our competition assays using preassembled heterodimers demonstrate that BACH1/sMafG can displace NRF2/sMafG from the DNA with similar efficiency as NRF2/sMafG displaces BACH1/sMafG (

Figure 5A,B). In both cases, comparable amounts of titrants are sufficient to achieve displacement. This supports the notion that relative protein abundance is one of the key determinants of transcriptional regulation at CsMBE promoters. This is particularly relevant given that both NRF2 and BACH1 are regulated at the protein level by E3 ligases [

9,

10,

36].

We observed that the displacements of DBDs from the DNA are more efficient when they are assembled as heterodimers. This can be explained by the structural and thermodynamic features inherent to bZIP architecture. Indeed, when BACH1DBD competes with NRF2 in a NRF2/sMafG complex, the process likely requires dissociation of the homodimer, which imposes an energetic barrier. Once displaced, NRF2DBD might not be as stable than when engaged with sMafG. Likewise, if indeed NRF2DBD is disordered in solution, folding of the basic region—and potentially the leucine zipper—would carry an additional energetic cost required to displace BACH1DBD from a BACH1/sMafG complex. Similarly, when displaced, BACH1DBD will have the hydrophobic leucine zipper exposed, which is likely to be less stable than when engaged in a dimer. These considerations support a model in which preassembled heterodimers are thermodynamically and kinetically favoured for the efficient bZIP exchange at CsMBE elements, at least in in vitro conditions.

A central finding of this study is that BACH1’s DNA-binding capacity is impaired in a C574-dependent manner. Free BACH1/sMafG heterodimer incubated under non-reducing conditions showed diminished DNA-binding competence, whereas the preformed BACH1/sMafG/DNA complex remained stable (

Figure 3B,C). These observations suggest that redox modifications at C574 either occur only when BACH1/sMafG is off the DNA or that C574 is protected once engaged on the DNA. Structural modelling places C574 adjacent to the DNA phosphate backbone, where oxidative modifications could sterically or electrostatically interfere with DNA contacts. Our competition assays further support this model: when oxidation preceded DNA binding, the displacement of BACH1/sMafG by NRF2/sMafG was markedly accelerated, but once assembled on the DNA, the complex resisted oxidation (

Figure 6C).

These findings are consistent with earlier work by Ishikawa et al. [

12], who showed that electrophiles such as diamide and HNE impair BACH1–DNA binding in cells, implicating C574 as a key regulatory site. Direct comparison, however, is challenging because of key differences in the experimental design: our assays use a reconstituted system containing only the DNA-binding domains, whereas Ishikawa’s observations were made in cells with the full-length protein. It therefore remains possible that electrophiles promote BACH1 release indirectly—for example, through heme release—and that C574 is subsequently modified in the unbound protein, thereby preventing re-binding. Alternatively, the redox modifications observed in our system may occur only when BACH1 is off DNA and not when it is engaged with sMafG on the DNA. Together, the cellular findings of Ishikawa and our biochemical data support a unified model in which the redox modifications of C574 attenuate the ability of BACH1 to (re)engage CsMBE sites.