Abstract

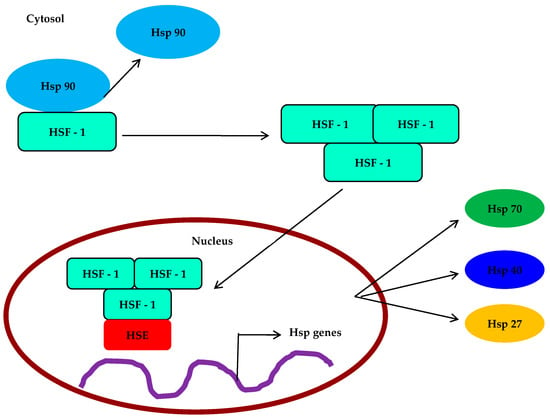

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) encompass both extrinsic chaperones and stress proteins. These proteins, with molecular weights ranging from 14 to 120 kDa, are conserved across all living organisms and are expressed in response to stress. The upregulation of specific genes triggers the synthesis of HSPs, facilitated by the interaction between heat shock factors and gene promoter regions. Notably, HSPs function as chaperones or helper molecules in various cellular processes involving lipids and proteins, and their upregulation is not limited to heat-induced stress but also occurs in response to anoxia, acidosis, hypoxia, toxins, ischemia, protein breakdown, and microbial infection. HSPs play a vital role in regulating protein synthesis in cells. They assist in the folding and assembly of other cellular proteins, primarily through HSP families such as HSP70 and HSP90. Additionally, the process of the folding, translocation, and aggregation of proteins is governed by the dynamic partitioning facilitated by HSPs throughout the cell. Beyond their involvement in protein metabolism, HSPs also exert a significant influence on apoptosis, the immune system, and various characteristics of inflammation. The immunity of aquatic organisms, including shrimp, fish, and shellfish, relies heavily on the development of inflammation, as well as non-specific and specific immune responses to viral and bacterial infections. Recent advancements in aquatic research have demonstrated that the HSP levels in populations of fish, shrimp, and shellfish can be increased through non-traumatic means such as water or oral administration of HSP stimulants, exogenous HSPs, and heat induction. These methods have proven useful in reducing physical stress and trauma, while also facilitating sustainable husbandry practices such as vaccination and transportation, thereby offering health benefits. Hence, the present review discusses the importance of HSPs in different tissues in aquatic organisms (fish, shrimp), and their expression levels during pathogen invasion; this gives new insights into the significance of HSPs in invertebrates.

1. Introduction

Due to the poikilothermic nature of aquatic animals, minor changes in the environment might lead to stress in fish. Fish are often exposed to various environmental stressors, such as pathogens, toxic gases, trauma, temperature fluctuations, and hypoxia. These factors, often referred to as stressors or stress factors, hold significant importance in determining the sequence of events that unfolds after encountering adverse consequences such as microbial infections, toxic exposure, traumatic injury, radiation, or nutritional deficiencies [1]. According to Selye’s [2] original definition from 1950, a normal metabolism is the objective that an animal strives to maintain or restore in the presence of chemical or physical stimuli. Easton [3] further proposed that stress occurs when an environmental or associated factor pushes an animal’s adaptive responses beyond its standard parameters or severely disrupts the animal’s proper functioning, ultimately reducing the probability of survival. This definition closely aligns with the circumstances observed in aquatic species. The term “general adaptation syndrome” (GAS) is used to describe the changes that occur in response to stress. It encompasses a sequence of biochemical and physiological changes that unfold in three stages: the alarm reaction (stage of resistance), during which adaptations are made to achieve homeostasis under the new conditions; the stage of exhaustion, where adaptations fail to restore homeostasis; and, if homeostasis is not achieved, it leads to a further decline in the probability of survival. The components of GAS are not specific to particular species or stressors, but the overall response to each stressor may vary significantly [4].

Research on the general adaptation syndrome in fish has primarily focused on hormonal and nervous responses. The role of the hypothalamic–pituitary internal axis in the GAS in fish has been extensively reviewed by Sumpter (1997) [5]. The impact of stress-mediated hormonal changes on the immune responsiveness of the animal, leading to increased susceptibility to infection, has been extensively discussed by Wedemeyer (1997) [6]. For further information on this aspect of GAS, readers are referred to these authors. Although the cellular stress response has received less attention in higher animals, fish, and shellfish, it is an important feature of the GAS (Locke, 1997) [7]. Cells typically respond to stress by altering gene expression, resulting in the upregulation of highly conserved proteins, collectively known as heat shock proteins (HSPs). These HSP molecules, produced in response to stressful conditions, not only play a crucial role in the early response to stressors but also contribute to host defenses against neoplasia and chronic pathogens. They may even hold potential as a primary avenue for the development of new vaccines, while being fundamental to evolution and all forms of life. Considering the growing interest in harnessing the induction of HSPs for clinical purposes in human medicine [8], methods for their induction are also emerging for veterinary purposes [9,10]. This review aims to explore the nature of the HSP response, its relevance to aquatic animals and their welfare, and recent research on methods of inducing HSPs in aquaculture, particularly concerning health and welfare issues.

2. Different Types of Stress Factors Involved in the Expression of HSPs

2.1. Desiccation, Temperature, and Hypoxia/Anoxia Stress

The impact of temperature on organisms is well recognized, as it can influence their physiology [11,12,13], behavior [14], and interactions with other species [15,16]. Thermal fluctuations are considered crucial factors that can disrupt physiological systems at the cellular and molecular levels [17]. Temperature affects molecular and physiological processes, influencing an organism’s activity patterns [18,19]. Aquatic organisms can exhibit physiological responses to acute temperature fluctuations before exhibiting behavioral responses [20]. Studies on marine species have shown that their thermal tolerance limits are determined by the onset of hypoxemia, which triggers the activation of anaerobic metabolic pathways [21]. In rocky shores, temperature and desiccation are recognized as key factors that set the upper limits of species distribution, with extreme desiccation stress leading to the diapause of crustacean eggs. However, organisms have developed adaptive mechanisms, including thermal tolerance, heat shock protein expression, and protein thermal stability, to counteract environmental extremes and minimize cell damage. The cellular stress response is activated to maintain cellular function and enhance the organism’s ability to cope with challenging situations [22]. This response involves the activation of cellular pathways such as proteolysis through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway and the increased production of heat shock proteins [23].

2.2. Osmotic Stress

Osmotic stress is a prevalent environmental factor that affects aquatic organisms. Osmoregulation, which is vital in maintaining osmotic homeostasis, plays a crucial role in response to this type of stress. The influence of stressors such as temperature or salinity on organisms has been studied extensively [24,25]. These stressors can impact the osmoregulation capability of organisms by affecting Na+-K+ ATPase activity or inducing heat shock protein production [26], both of which contribute to maintaining relative osmotic hemolymph homeostasis [27]. Numerous studies have investigated the expression patterns of heat shock proteins (HSPs) under salinity stress. For example, the expression of HSP90 was induced in Crassostrea hongkongensis [28] and Eriocheir sinensis [26,29] under osmotic stress. High salinity stress led to the significant upregulation of HSP70 expression in the hemocytes of Scylla paramamosain [30]. In the hepatopancreas of Portunus trituberculatus, HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90 showed either downregulated or upregulated expression profiles when exposed to low salinity (4 ppt) [31]. These findings suggest that HSPs play a role in mediating the effects of salinity stress in aquatic crustaceans.

2.3. Ultraviolet Radiation Stress

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, an abiotic factor, can have detrimental effects on organisms, both directly and indirectly. Direct exposure to UV radiation can lead to changes in protein synthesis and DNA due to the absorption of high-energy photons. Indirectly, UV radiation can generate reactive oxygen species that cause damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids [32,33,34]. The impact of UV radiation on aquatic organisms has become a significant concern in recent years. Research conducted on calanoid copepods has shown that UV-induced stress can impair feeding mechanisms and digestion and disrupt the entire food chain [35]. UV radiation directly and indirectly influences the survival, growth, and reproduction of organisms, and it led to the increased expression of antioxidant enzymes and heat shock protein (HSP) genes in the copepod Paracyclopina nana [34].

2.4. Heavy Metal Stress

Heavy metals pose a significant problem as a cause of pollution in water, soil, and plants. They enter water sources through seepage from household or industrial waste, resulting in serious risks to aquatic ecosystems and aquaculture animals. In laboratory studies focusing on crustaceans, the impact of heavy metals on gene expression changes has been extensively examined. Commonly tested heavy metals include copper (Cu), silver (Ag), zinc (Zn), lead (Pb), manganese (Mn), arsenic (As), and cadmium (Cd) [36,37,38]. Heavy metal stress is closely linked to the induction of oxidative stress. In seawater, heavy metals can trigger oxidative stress in various organisms, including the marine crab Portunus trituberculatus [39]. This type of oxidative stress disrupts the cellular redox balance, prompting a protective stress response. Numerous studies on aquatic organisms, particularly crustaceans, have demonstrated that heavy metal stress significantly stimulates the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes [40] and heat shock proteins [26,38]. Heat shock proteins (HSP) appear to play a crucial role in the innate immune systems and stress responses of crustaceans [36,37,38].

2.5. Effect of Endocrine Disruptor Chemicals in Heat Shock Proteins

Endocrine disruptor chemicals (EDCs) are compounds that imitate natural hormones, inhibiting their activity or altering their normal regulatory function within the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems [41]. These chemicals are ecotoxicologically significant as they have a tendency to be absorbed onto humic material or accumulate in aquatic organisms, persisting in water or the food web for extended periods. Consequently, their effects can induce prolonged stress in aquatic organisms. Various EDCs, including pesticides, bisphenol A, phthalates, dioxins, and phytoestrogens, have been shown to interact with the female reproductive system and cause endocrine disruption [42]. Endosulfan and deltamethrin, commonly used pesticides in shrimp farms [43], are particularly noteworthy. Endosulfan is widely employed as a broad-spectrum insecticide, primarily in agriculture, and is highly toxic to aquatic organisms [44,45,46]. Studies investigating the stress response induced by EDCs have indicated the significant induction of heat shock protein (HSP) family proteins [47,48,49], detoxification enzymes such as glutathione S-transferases [50], and superoxide dismutase. These proteins are considered to potentially contribute to the protection of aquatic organisms against stress.

2.6. Other Toxicants

Apart from the previously mentioned primary chemicals, there exist a significant number of other toxic substances in the habitats of aquatic organisms. These toxicants include hydrocarbons, diatom toxins, emamectin benzoate, nitrite, and prooxidant chemical hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), among others. They accumulate in aquatic and/or terrestrial environments through the release of household and/or industrial waste. Research studies have demonstrated that these toxicants can have harmful effects on crustaceans [51,52]. In a study conducted by Lauritano et al. [41], it was observed that feeding on a diatom species (Skeletonema marinoi) that produced strong oxylipins for only two days led to the significant downregulation of heat shock proteins (HSP40 and HSP70) in the copepod Calanus helgolandicus. Diatom oxylipins are known to induce the generation of free radicals, including reactive oxygen species, which can cause oxidative stress and cellular damage. Furthermore, nitrite is considered one of the most prevalent pollutants in aquaculture due to its numerous integrated effects. A study on shrimp demonstrated that oxidative stress was one of the mechanisms of nitrite toxicity [53]. Guo et al. [53] confirmed that exposure to nitrite induced the expression of apoptosis-related genes in hemocytes, while also upregulating the expression levels of HSP70 and antioxidant enzymes to protect against nitrite-induced stress.

3. The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Aquaculture Disease Management

3.1. Immunology and Stress Response

The identification of heat shock proteins (HSP) initially occurred in Drosophila busckii as a response to stress [54]. Since then, their roles as chaperones in protecting cellular proteins from denaturation have garnered significant interest [55,56]. In aquaculture animals, HSPs have been the focus of numerous studies due to their crucial function in mitigating the stress-induced denaturation of client proteins, as well as their involvement in protein folding, assembly, degradation, and gene expression regulation [57,58]. Physiological and environmental stressors, including high thermal shock, heavy metals, free radicals, desiccation, and microbial infection, can induce the synthesis of HSPs. This induction is considered a vital protective response that is conserved across organisms, enabling them to adapt to environmental challenges. Recent research has revealed the involvement of heat shock chaperonins in autoimmune and innate immune responses in various species, including crustaceans. HSPs play a crucial role in mounting protective immune responses against bacterial and viral diseases [59,60]. In the crustacean aquaculture industry, which faces substantial economic losses due to environmental stressors, investigations into heat shock proteins have gained popularity. These proteins play vital roles in conferring resistance to diverse stressors. Extensive research has been conducted to understand the structures, functions, cross-talk, immune response mechanisms, and innate immune pathways of HSPs in crustaceans when exposed to various environmental stressors or xenobiotics. Exploiting HSPs as a means of preventing and treating aquaculture diseases in commercially cultured aquatic organisms is crucial as it provides an alternative to the use of antibiotics and therapeutic drugs [61]. Furthermore, previous studies have aimed to identify effective strategies for the management of environmental stressors in aquaculture settings for aquatic organisms [62].

3.2. Crustaceans: Exploring the Link between Environmental Stresses and Disease

Crustacean aquaculture plays a significant role in the economies of several countries worldwide. However, the expansion and intensification of aquaculture farms have led to the emergence of various new diseases in commercially cultivated species. Disease outbreaks caused by viruses, bacteria, and environmental stressors pose a serious threat to the global crustacean aquaculture industry, resulting in substantial economic losses. Unlike vertebrates, invertebrates lack true adaptive immunity and have developed defense systems that respond to physiological and environmental stresses [16,63]. During crustacean aquaculture, organisms are constantly exposed to environmental stimuli and a range of natural and anthropogenic stressors (Table 1). Numerous studies have demonstrated that physical stressors such as temperature, salinity, and UV radiation, as well as chemical stressors such as endocrine disruptor chemicals, heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and other toxicants, can be detrimental to crustacean cells. Moreover, in natural ecosystems, multiple environmental forces interact, resulting in situations of combined stress [64,65]. Crustaceans possess an innate immune system, which serves as their first line of defense and responds to natural and anthropogenic stimuli, pollutants, and toxins [41,66]. Studies have indicated that certain metabolic enzymes (such as cytochrome P450, glutathione S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, etc.), heat shock proteins, and immune-related proteins in crustaceans play a role in enhancing disease tolerance and aiding the elimination of harmful compounds from their bodies [41,67].

Table 1.

Expression of HSPs in crustaceans under varying stress conditions and their responses.

Shellfish Diseases and the Role of Pathogens

Shellfish diseases are prevalent and frequently observed in various commercially exploited crustacean species. Currently, a range of pathogens, including Vibrio, chitinoclastic bacteria, Aeromonas, Spiroplasma, Rickettsia-like organisms, Chlamydia-like organisms, Rhodobacteriales-like organisms, white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), yellow head virus (YHV), infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV), Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) microsporidian parasites, and covert mortality nodavirus (CMNV), have been identified as causes of disease in crustaceans [93]. Vibrio species, found in various marine and freshwater crustaceans, are widespread worldwide. Vibrio infections commonly result in bacteremia and shell diseases [94]. For instance, Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection caused acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and led to significant mortality in a penaeid shrimp aquaculture [95]. Chitinolytic or chitinoclastic bacteria are often associated with shellfish diseases, leading to unsuccessful molting in crustaceans [96] or septicemic infections caused by opportunistic pathogenic bacteria [97]. Infections by other pathogens, such as Rickettsia-like organisms, Chlamydia-like organisms, spiroplasma, and Rhodobacteriales-like organisms, have caused severe stress or fatal diseases in crustaceans. Efforts have been made by numerous researchers to find effective methods to control bacterial diseases. Recent studies have shown that synbiotics can induce penaeid shrimp immunity and promote the growth of aquatic animals [98]. Oxytetracycline has been found to be highly effective in treating spiroplasma disease [99]. Several immune-related genes and proteins, including tachylectin-like genes and proteins and heat shock proteins [67], have been identified as being involved in shrimp tolerance to AHPND-causing strains. Crustacean fibrinogen-related proteins have also been found to participate in the innate immune response during AHPND or other pathogen infections [100]. Additionally, viruses continue to pose a significant challenge to crustacean aquaculture. Recent research has highlighted several new and emerging diseases in shrimp, including hepatopancreatic microsporidiosis, hepatopancreatic haplosporidiosis, aggregated transformed microvilli, covert mortality disease, white spot disease, yellow head disease, infectious myonecrosis, and white tail disease, which represent major viral threats to commercially cultivated shrimp [93].

3.3. Expression of Heat Shock Proteins in Fish

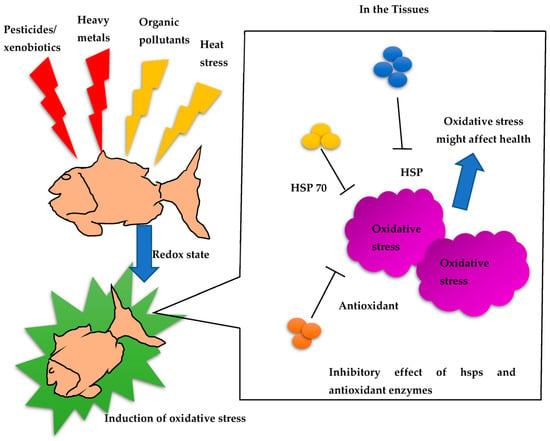

The presence of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in fish has been extensively documented, emphasizing their importance in responding to stress and safeguarding cellular integrity. HSPs are a group of highly conserved proteins that serve as molecular chaperones, aiding in the folding, assembly, and breakdown of other proteins. Fish exhibit increased HSP production when exposed to various stressors, such as elevated temperatures, exposure to heavy metals, oxidative stress, and infection by pathogens. Numerous studies have observed the heightened expression of HSPs in different fish species, including zebrafish (Danio rerio), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), in response to stressors [101,102] (Table 2). These HSPs play a vital role in maintaining cellular balance, facilitating fish survival, and enabling adaptation to adverse environmental conditions. Furthermore, HSPs have been implicated in fish immune responses, enhancing their ability to defend against bacterial and viral infections [103]. The monitoring of HSP expression in fish serves as a valuable method to assess environmental stress levels and evaluate the overall health of fish populations in aquatic ecosystems (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Expression of HSPs in various parts of fish under stress conditions.

Figure 1.

Redox signaling mechanisms and inhibitory effects of HSPs in fish.

3.4. Expression of Heat Shock Proteins in Mollusk

The expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs) is associated with important developmental processes in various species, including gametogenesis, embryogenesis, and metamorphosis. In marine invertebrates with a biphasic life cycle, where pelagic larvae undergo settlement and metamorphosis, research has revealed interesting findings. For instance, studies on Eastern oyster C. virginica larvae and early spat have shown the presence of three HSP70 isoforms: HSC77, HSC72, and HSP69. The expression of constitutive and inducible forms of HSP70 differs among the larval and early juvenile stages and in response to thermal stress. Interestingly, the low expression of HSP69 during early larval and spat development may contribute to their vulnerability to environmental stress. In another investigation, Gunter and Degnan examined how the marine gastropod Haliotis asinine expresses HSP90, HSP70, and the heat shock transcription factor (me) during development (Table 3). HSP70, HSP90, and HSF are first expressed in this species by maternal contribution, before being gradually confined to the micromere lineage after cleavage (Figure 2). These proteins are expressed in distinct ways in the prototroch, foot, and mantle during larval morphogenesis. When cells are differentiating and undergoing morphogenesis, their expression is at its highest; however, after morphogenesis is complete, it starts to decline.

Table 3.

Mollusk expression of heat shock proteins in different organs with varying stress conditions.

Figure 2.

Expression and molecular mechanisms of HSP and HSF in Mollusca.

3.5. Heat Shock Protein Expression in Insects

A group of conserved polypeptides collectively known as heat shock proteins (HSPs) are rapidly increased in synthesis by insects in response to high temperatures and a variety of chemical and physical stimuli. Hspshave molecular-weight-based names, such as Hsp10, Hsp40, Hsp60, Hsp70, Hsp90, and Hsp100. Small Hsps (sHsp) are a subclass of Hsps that play a role in the folding and unfolding of other proteins (Table 4). In the fruit fly Drosophila busckii, Ritossa was the first to note that heat and the metabolic uncoupler dinitrophenol caused a distinctive pattern of puffing in the salivary gland chromosomes [54]. This discovery ultimately helped to identify the Hsps that these puffs were representing. The first observation of the increased production of certain proteins in Drosophila cells in response to stressors such as heat shock was made in 1974 [170]. There is currently a vast body of research that describes the extensive spectrum of action taken by cells in response to a wide range of biotic and abiotic stressors in a variety of insects [171,172].

Table 4.

Roles of different stressors in the responses and expression of heat shock proteins in insects.

3.6. Heat Shock Proteins in Myxozoan Parasites (Cnidaria)

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are expressed by parasites as a response to various stimuli, such as heat and oxidative stress. These HSPs provide parasites with resistance to these harsh conditions, which is crucial for their survival. The genes associated with protein refolding, including HSP60, HSP70, and HSP80 family members, express these heat shock proteins. Apart from their role in protein refolding, HSPs also show significant involvement in other processes, such as maintaining protein balance and stability. They have the ability to bind to abnormal forms of proteins and facilitate their folding into their natural conformations. T. bryosalmonae, a parasite, faces the challenge of overcoming the robust immune responses mounted by both brown trout and rainbow trout [185]. This challenge potentially affects various physiological processes of T. bryosalmonae, including protein structure and function. Moreover, HSPs found in several parasites, such as T. cruzi [186] and Schistosomes [187], have been discovered to elicit an immune response in their respective hosts and are immunogenic in nature. In a recent study, it was found that myxozoan parasites such as Ceratonova shasta, Myxobolus cerebralis, and Sphaerospora molnari from the intestine and abdominal cavity (ascitic fluid) of rainbow trout expressed HSP70 when exposed to oxidative stress [188].

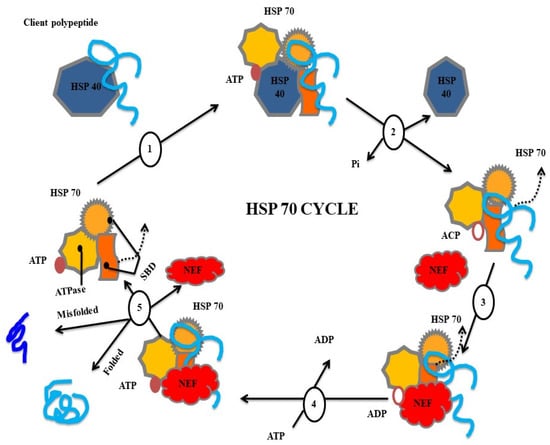

4. Defense Mechanisms of Heat Shock Proteins

The heat shock protein family, such as HSP70, are primarily studied for disease control purposes, but other members, such as small heat shock proteins (sHSPs), including HSP60 and HSP90, alongside HSP40/co-chaperone, have shown potential in treating pathogen infections. sHSPs act as oligomeric platforms, binding structurally perturbed proteins without requiring ATP, thereby preventing their irreversible denaturation under cellular stress. HSP90, HSP70, and HSP60 are stress-induced and provide protection against irreversible protein denaturation. However, their primary function involves binding and folding newly synthesized proteins through allosteric rearrangement, which is driven by ATP, although the mechanisms of action and the molecular structure differ among the chaperone families. In cooperation, these HSPs form intracellular networks with accessory proteins and other co-chaperones. sHSP monomers are a group of conserved α-crystallin domains flanked by carboxyl- and amino-terminal sequences and assemble into oligomers. The α-crystallin domain facilitates monomer dimerization and substrate binding, with the efficiency depending on the terminal region. During stress, sHSP oligomers may undergo structural rearrangement or disassemble, which promotes substrate protein interactions and increases surface hydrophobicity. Upon stress resolution, proteins released from sHSPs have the ability to spontaneously refold with the assistance of HSP70, which is an ATP-dependent HSP [189]. The key role of sHSPs is to prevent protein denaturation, which is irreversible during infection and stress.

In aquatic organisms, such as the white shrimp (L. vannamei) and Scrippsiella trochoidea, various HSP genes (e.g., LvHSP40, LvHSP60, LvHSP70, LvHSC70, and LvHSP90) are significantly induced under acute thermal stress, highlighting their sensitivity to temperature fluctuations. Shrimp HSPs are also highly expressed in response to pathogen infections, as demonstrated by the upregulation of LvHsp60 in the gills, hemocytes, and hepatopancreas after challenge with Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria. Furthermore, the use of plant-based polyphenolic compounds such as phloroglucinol and carvacrol has been shown to result in the induction of HSP70 and protection against bacterial infection in brine shrimp and freshwater prawns [190]. These findings suggest that HSPs may play a role in crustaceans’ immune system regulation, which triggers immune defense against diseases, as evidenced by the modulation of immune-related genes. Overall, the investigation of HSPs in aquatic organisms provides insights into their involvement in combating stress and infection, offering potential avenues for disease control and enhancing the immune responses in these organisms.

Biotic stress factor bacteria induce HSP20 expression in fish [191,192]. Similarly, some sHsp cDNA have been isolated and characterized in an expression analysis performed in fish [117,128,193,194,195]. Following this, the HSP expression level was detected in Ictalurus punctatus [196], Paralichthys olivaceus [197], and Epinephelus coioides [198]. However, the expression patterns of fish sHsp under environmental stress are still limited with regard to biotic stress factors. Another type of HSP21 transcript was induced after 24 h exposure to Vibrio harveyi in shrimp P. monodon [158]; this was found to be entirely different in WSSV infection with P. monodon [199]. M. rosenbergii showed upregulated expression of HSP37 mRNA in the hepatopancreas under an infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus challenge [200]. In disk abalone Haliotis discus, HSP20 expression reached its highest peak in V. parahemolyticus with the VHSV virus [201]. Although some sHsp cDNA have been isolated and characterized in fish, there is little research on their roles in the immune response [117,128,193,194,195]. Recently, it was validated that, when infected with Singapore grouper iridovirus (SGIV) and V. alginolyticus, Epinephelus coioides hsp22 mRNA expression was significantly increased, and HSP22 could significantly inhibit the SGIV-induced cell apoptosis [202].

Importantly, abiotic factors also interact with the expression levels of HSPs in aquatic organisms, among which temperature can influence the growth, reproduction, and survival of aquatic organisms (fish and shellfish) and result in serious losses in aquaculture (Figure 3) [203,204]. In a study, the existing HSP20 gene expression was regulated by heat stress [191,192,200,205]. However, few reports provide information about the temperature regulation of HSP20 in fish, and the HSP expression levels in fish under stress factors are poorly understood. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the findings regarding HSP expression in a range of aquatic organisms with regard to biotic and abiotic stress factors, as the gene expression profile can reveal the importance of their enhancement against foreign stimuli/invaders.

Figure 3.

Types of heat shock proteins involved in folding and misfolding mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Our understanding of the chaperone system of HSPs and its significance in farmed aquatic organisms is still limited, but progress is being made in medical and veterinary research. There have been rapid advances in comprehending the fundamental aspects of HSP genes and the effects of their products and their regulation on cell maintenance, as well as cell signaling, inflammation, and the immune response. This knowledge has been applied to various veterinary and human clinical situations, and promising results have been obtained during the initial development of HSP vaccines derived from pathogens. These advancements indicate the potential value of HSPs in numerous areas of aquatic science. Further exploration of the HSP chaperone system and its applications could have significant implications for the health and wellbeing of farmed aquatic animals, providing opportunities for advancements in aquaculture practices, disease prevention, and overall aquatic ecosystem management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and K.P.; methodology, S.J. and H.C.; software, S.J.; validation, S.J., I.-S.K. and H.C.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, H.C.; resources, I.-S.K. and S.J.; data curation, K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C. and K.P.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and K.P.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, I.-S.K. and S.J.; project administration, S.J.; funding acquisition, I.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, Republic of Korea, which is funded by the Korean Government [NRF-2018-R1A6A1A-03024314].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study will be disclosed upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roberts, R.J.; Agius, C.; Saliba, C.; Bossier, P.; Sung, Y.Y. Heat shock proteins (chaperones) in fish and shellfish and their potential role in relation to fish health: A review. J. Fish Dis. 2010, 33, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selye, H. Stress; Acta: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D.P.; Rutledge, P.S.; Spotila, J.R. Heat shock protein induction and induced thermal tolerance are independent in adult salamanders. J. Exp. Zool. 1987, 241, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, K.E.; Dickerson, R.R.; Huffman, G.J.; Boatman, J.F.; Schanot, A. Trace gas transport in the vicinity of frontal convective clouds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1988, 93, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, J.P. The endocrinology of stress. In Fish Stress and Health in Aquaculture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; Volume 819, pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wedemeyer, G.A. Effects of rearing conditions on the health and physiological quality of fish in intensive culture. In Fish Stress and Health in Aquaculture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, M. The cellular stress response to exercise: Role of stress proteins. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 1997, 25, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.K. New Jobs for Ancient Chaperones. Sci. Am. 2008, 299, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinod, S.R.; Bernard, B.; Serrar, M.; Gutierrez, G. Release of heat-shock protein Hsp72 after exercise and supplementation with an Opuntia ficus indica extract TEX-OE. In Proceedings of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, Orlando, FL, USA, 1–5 December 2007; Volume 53, pp. 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sandilands, J.; Drynan, K.; Roberts, R.J. Preliminary studies on the enhancement of storage time of chilled milt of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., using an extender containing the Tex-OE®heat shock-stimulating factor. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomanek, L. Variation in the heat shock response and its implication for predicting the effect of global climate change on species’ biogeographical distribution ranges and metabolic costs. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somero, G.N. The Physiology of Global Change: Linking Patterns to Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.D.; Harmer, D.W.; Coleman, R.A.; Clark, B.J.; Namachivayam, K.; Blanco, C.L.; MohanKumar, K.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Vasquez, M.; McGill-Vargas, L.; et al. GAPDH as a housekeeping gene: Analysis of GAPDH mRNA expression in a panel of 72 human tissues. Physiol. Genom. 2005, 21, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, R.B. Physiological Consequences of Habitat Selection. Am. Nat. 1991, 137, S91–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, N.J.; Lewis, J.W. Temperature stress and parasitism of endothermic hosts under climate change. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labaude, S.; Moret, Y.; Cézilly, F.; Reuland, C.; Rigaud, T. Variation in the immune state of Gammarus pulex (Crustacea, Amphipoda) according to temperature: Are extreme temperatures a stress? Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 76, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossins, A.R.; Bowler, K. Rate compensations and capacity adaptations. In Temperature Biology of Animals; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 155–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, M.C. Effect of temperature on the survival and growth of freshwater prawns Macrobrachium borellii and Palaemonetes argentinus (Crustacea, Palaemonidae). Iheringia Série Zool. 2011, 101, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Habashy, W.; Ghoname, M.; Elnaggar, A. Blood hematology and biochemical of four laying hen strains exposed to acute heat stress. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedulina, D.; Meyer, M.F.; Gurkov, A.; Kondratjeva, E.; Baduev, B.; Gusdorf, R.; Timofeyev, M.A. Intersexual differences of heat shock response between two amphipods (Eulimnogammarus verrucosus and Eulimnogammarus cyaneus) in Lake Baikal. PeerJ 2017, 5, e2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H. Climate variations and the physiological basis of temperature dependent biogeography: Systemic to molecular hierarchy of thermal tolerance in animals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 132, 739–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.P.; Thatje, S.; Hauton, C. The use of stress-70 proteins in physiology: A re-appraisal. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, D.; Mendonça, V.; Dias, M.; Roma, J.; Costa, P.M.; Larguinho, M.; Vinagre, C.; Diniz, M.S. Physiological, cellular and biochemical thermal stress response of intertidal shrimps with different vertical distributions: Palaemon elegans and Palaemon serratus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 183, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmantier, G.U.Y. Ontogeny of osmoregulation in crustaceans: A review. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1998, 33, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R. Ionic regulation in fish: The influence of acclimation temperature on plasma composition and apparent set points. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Physiol. 1986, 85, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhang, D.; Pan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Yang, X. ZmHSP16.9, a cytosolic class I small heat shock protein in maize (Zea mays), confers heat tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, N.; Zeng, C. The effects of salinity on the survival, growth and haemolymph osmolality of early juvenile blue swimmer crabs, Portunus pelagicus. Aquaculture 2006, 260, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z. Cloning and expression of a heat shock protein (HSP) 90 gene in the haemocytes of Crassostrea hongkongensis under osmotic stress and bacterial challenge. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 31, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Y.; Song, C.; Shi, G. Transcriptome Analysis and Discovery of Genes Involved in Immune Pathways from Hepatopancreas of Microbial Challenged Mitten Crab Eriocheir sinensis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, H.; Huang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Zeng, X.; Gong, J. Expression of Hsp70 in the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain in response to bacterial, osmotic, and thermal stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2013, 18, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Mu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Li, R.; Wang, C. mRNA expression profiles of heat shock proteins of wild and salinity-tolerant swimming crabs, Portunus trituberculatus, subjected to low salinity stress. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 6837–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.-O.; Rhee, J.-S.; Won, E.-J.; Lee, K.-W.; Kang, C.-M.; Lee, Y.-M.; Lee, J.-S. Ultraviolet B retards growth, induces oxidative stress, and modulates DNA repair-related gene and heat shock protein gene expression in the monogonont rotifer, Brachionus sp. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-M.; Rhee, J.-S.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, M.-J.; Shin, K.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Lee, J.-S. UV-B radiation-induced oxidative stress and p38 signaling pathway involvement in the benthic copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 167, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, E.-J.; Han, J.; Lee, Y.; Kumar, K.S.; Shin, K.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Park, H.G.; Lee, J.-S. In vivo effects of UV radiation on multiple endpoints and expression profiles of DNA repair and heat shock protein (Hsp) genes in the cycloid copepod Paracyclopina nana. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 165, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacuna, D.G.; Uye, S.-I. Influence of mid-ultraviolet (UVB) radiation on the physiology of the marine planktonic copepod Acartia omorii and the potential role of photoreactivation. J. Plankton Res. 2001, 23, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamuna, A.; Kabila, V.; Geraldine, P. Expression of heat shock protein 70 in freshwater prawn Macrobrachium malcolmsonii (H. Milne Edwards) following exposure to Hg and Cu. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2000, 38, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-M.; Rhee, J.-S.; Jeong, C.-B.; Seo, J.S.; Park, G.S.; Lee, Y.-M.; Lee, J.-S. Heavy metals induce oxidative stress and trigger oxidative stress-mediated heat shock protein (hsp) modulation in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 166, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestana, J.L.; Novais, S.C.; Norouzitallab, P.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Bossier, P.; De Schamphelaere, K.A. Non-lethal heat shock increases tolerance to metal exposure in brine shrimp. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Zheng, C.-J.; Liu, J.; Hu, H.-J. Identification of two hsp90 genes from the marine crab, Portunus trituberculatus and their specific expression profiles under different environmental conditions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 150, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-J.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kumar, V. Heavy metal toxicity: An update of chelating therapeutic strategies. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 54, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritano, C.; Procaccini, G.; Ianora, A. Gene expression patterns and stress response in marine copepods. Mar. Environ. Res. 2012, 76, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M.F.; Spritzer, P.M.; Hohl, A.; Bachega, T.A.S.S. Effects of endocrine disruptors in the development of the female reproductive tract. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2014, 58, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Niu, L.; Liu, W.; Xu, C. Embryonic exposure to butachlor in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Endocrine disruption, developmental toxicity and immunotoxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 89, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, C.; Thompson, S.; Ritz, B.; Cockburn, M.; Heck, J.E. Residential proximity to pesticide application as a risk factor for childhood central nervous system tumors. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defur, P.L. Use and Role of Invertebrate Models in Endocrine Disruptor Research and Testing. ILAR J. 2004, 45, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capkin, E.R.O.L.; Altinok, I.; Karahan, S. Water quality and fish size affect toxicity of endosulfan, an organochlorine pesticide, to rainbow trout. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.S.; Park, T.-J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Park, H.G.; Yoon, Y.-D.; Lee, J.-S. Small Heat Shock Protein 20 Gene (Hsp20) of the Intertidal Copepod Tigriopus japonicus as a Possible Biomarker for Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006, 76, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorts, J.; Silvestre, F.; Tu, H.T.; Tyberghein, A.-E.; Phuong, N.T.; Kestemont, P. Oxidative stress, protein carbonylation and heat shock proteins in the black tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon, following exposure to endosulfan and deltamethrin. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 28, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocci, P.; Capriotti, M.; Mosconi, G.; Palermo, F.A. Effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals on estrogen receptor alpha and heat shock protein 60 gene expression in primary cultures of loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) erythrocytes. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.B.; Park, C.H.; Choi, J. Expression of heat shock protein and hemoglobin genes in Chironomus tentans (Diptera, chironomidae) larvae exposed to various environmental pollutants: A potential biomarker of freshwater biomonitoring. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianora, A.; Miralto, A.; Poulet, S.A.; Carotenuto, Y.; Buttino, I.; Romano, G.; Casotti, R.; Pohnert, G.; Wichard, T.; Colucci-D’Amato, L.; et al. Aldehyde suppression of copepod recruitment in blooms of a ubiquitous planktonic diatom. Nature 2004, 429, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.H.; Altin, D.; Rørvik, S.F.; Øverjordet, I.B.; Olsen, A.J.; Nordtug, T. Comparative study on acute effects of water accommodated fractions of an artificially weathered crude oil on Calanus finmarchicus and Calanus glacialis (Crustacea: Copepoda). Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xian, J.-A.; Li, B.; Ye, C.-X.; Wang, A.-L.; Miao, Y.-T.; Liao, S.-A. Gene expression of apoptosis-related genes, stress protein and antioxidant enzymes in hemocytes of white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei under nitrite stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 157, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritossa, F. A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in drosophila. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1962, 18, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.M. Stress Proteins in Aquatic Organisms: An Environmental Perspective. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1993, 23, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, M.E.; Hofmann, G.E. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: Evolutionary and Ecological Physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1999, 61, 243–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piano, A.; Franzellitti, S.; Tinti, F.; Fabbri, E. Sequencing and expression pattern of inducible heat shock gene products in the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis. Gene 2005, 361, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, K.; Minami, M.; Minami, Y. Constantly Updated Knowledge of Hsp90. J. Biochem. 2005, 137, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habich, C.; Burkart, V. Heat shock protein 60: Regulatory role on innate immune cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, Y.Y.; MacRae, T.H. Heat Shock Proteins and Disease Control in Aquatic Organisms. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2011, s2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, M.K.; Nizam, F.; Ravichandran, G.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Arshad, A.; Elumalai, P.; Arockiaraj, J. Molecular importance of prawn large heat shock proteins 60, 70 and 90. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 48, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.; Becher, M.A.; Osborne, J.L.; Kennedy, P.J.; Aupinel, P.; Bretagnolle, V.; Brun, F.; Grimm, V.; Horn, J.; Requier, F. Predictive systems models can help elucidate bee declines driven by multiple combined stressors. Apidologie 2017, 48, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla-Vazquez, M.A.; Matilla, A.J. Ethylene: Role in plants under environmental stress. In Physiological Mechanisms and Adaptation Strategies in Plants under Changing Environment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, J.M.J.; Travis, J.M.J.; Travis, J.M.J.; Travis, J.M.J. Climate change and habitat destruction: A deadly anthropogenic cocktail. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2003, 270, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehedin, A.; Piscart, C.; Marmonier, P. Seasonal variations of the effect of temperature on lethal and sublethal toxicities of ammonia for three common freshwater shredders. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowsky-Suzuki, B.; Koski, M.; Hallberg, E.; Wallén, R.; Carlsson, P. Glutathione transferase activity and oocyte development in copepods exposed to toxic phytoplankton. Harmful Algae 2009, 8, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junprung, W.; Supungul, P.; Tassanakajon, A. Structure, gene expression, and putative functions of crustacean heat shock proteins in innate immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 115, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, J.-S.; Raisuddin, S.; Lee, K.-W.; Seo, J.S.; Ki, J.-S.; Kim, I.-C.; Park, H.G.; Lee, J.-S. Heat shock protein (Hsp) gene responses of the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus to environmental toxicants. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 149, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Qiu, L.; Zhou, F.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, K. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a heat shock protein (Hsp90) gene from black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Xiang, J.; Wang, P. Gene expression profiles of four heat shock proteins in response to different acute stresses in shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 156, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Nong, W.; Wei, X.; Zhu, M.; Mao, L. Impacts of a novel live shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) water-free transportation strategy on flesh quality: Insights through stress response and oxidation in lipids and proteins. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, A.; Bernatowicz, P.; Grzesiuk, M.; Kloc, M.; Pijanowska, J. Differential Levels of Stress Proteins (HSPs) in Male and Female Daphnia magna in Response to Thermal Stress: A Consequence of Sex-Related Behavioral Differences? J. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 37, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haap, T.; Schwarz, S.; Köhler, H.-R. Metallothionein and Hsp70 trade-off against one another in Daphnia magna cross-tolerance to cadmium and heat stress. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 170, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W.-J.; Zhu, X.-J.; Karouna-Renier, N.K.; Rao, R.K. Molecular cloning and expression of two HSP70 genes in the prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Cell Stress Chaperones 2004, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeyev, M.A.; Shatilina, Z.M.; Bedulina, D.S.; Protopopova, M.V.; Pavlichenko, V.V.; Grabelnych, O.I.; Kolesnichenko, A.V. Evaluation of biochemical responses in Palearctic and Lake Baikal endemic amphipod species exposed to CdCl2. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 70, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, M.-J.S.J.; Schill, R.O.; Knigge, T.; Eckwert, H.; Kammenga, J.E.; Köhler, H.-R. Stress Proteins (hsp70, hsp60) Induced in Isopods and Nematodes by Field Exposure to Metals in a Gradient near Avonmouth, UK. Ecotoxicology 2004, 13, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.S. Stressed-Out Lobsters: Crustacean Hyperglycemic Hormone and Stress Proteins. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005, 45, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spees, J.L.; Chang, S.A.; Snyder, M.J.; Chang, E.S. Osmotic Induction of Stress-Responsive Gene Expression in the LobsterHomarus americanus. Biol. Bull. 2002, 203, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázque-Amado, R.M.; Escamilla-Chimal, E.G.; Fanjul-Moles, M.L. Daily Light-Dark Cycles Influence Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 and Heat Shock Protein Levels in the Pacemakers of Crayfish. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012, 88, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheller, R.A.; Smyers, M.E.; Grossfeld, R.M.; Ballinger, M.L.; Bittner, G.D. Heat-shock proteins in axoplasm: High constitutive levels and transfer of inducible isoforms from glia. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998, 396, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, J.S.; Jackson, S.A.; Van Hoa, N.; Sorgeloos, P. Thermal resistance, developmental rate and heat shock proteins in Artemia franciscana, from San Francisco Bay and southern Vietnam. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2000, 252, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.-J.; Zheng, C.-Q.; Wang, Y.-W.; Meng, C.; Xie, X.-L.; Liu, H.-P. Differential protein expression using proteomics from a crustacean brine shrimp (Artemia sinica) under CO2-driven seawater acidification. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 58, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, D.; Foucreau, N.; Hervant, F.; Piscart, C. Differential regulation of hsp70 genes in the freshwater key species Gammarus pulex (Crustacea, Amphipoda) exposed to thermal stress: Effects of latitude and ontogeny. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2015, 185, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedulina, D.S.; Timofeyev, M.A.; Zimmer, M.; Zwirnmann, E.; Menzel, R.; Steinberg, C.E.W. Different natural organic matter isolates cause similar stress response patterns in the freshwater amphipod, Gammarus pulex. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2010, 17, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruda, A.M.; Baumgartner, M.F.; Reitzel, A.M.; Tarrant, A.M. Heat shock protein expression during stress and diapause in the marine copepod Calanus finmarchicus. J. Insect Physiol. 2011, 57, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, L.; Dimant, B.; Suárez, L.D.; Portiansky, E.L.; Delorenzi, A. Food odor, visual danger stimulus, and retrieval of an aversive memory trigger heat shock protein HSP70 expression in the olfactory lobe of the crab Chasmagnathus granulatus. Neuroscience 2012, 201, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, K.; Jollivet, D.; Papot, C.; Léger, N.; Corre, E.; Ravaux, J.; Clark, M.S.; Toullec, J.-Y. Diversification, Evolution and Sub-Functionalization of 70kDa Heat-Shock Proteins in Two Sister Species of Antarctic Krill: Differences in Thermal Habitats, Responses and Implications under Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colson-Proch, C.; Morales, A.; Hervant, F.; Konecny, L.; Moulin, C.; Douady, C.J. First cellular approach of the effects of global warming on groundwater organisms: A study of the HSP70 gene expression. Cell Stress Chaperones 2010, 15, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.T.; Chu, K.H. Characterization of heat shock protein 90 in the shrimpMetapenaeus ensis: Evidence for its role in the regulation of vitellogenin synthesis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2008, 75, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Cao, J.; Mao, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides comprehensive insights into the heat stress response of Marsupenaeus japonicus. Aquaculture 2019, 502, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, J.; Chen, P.; Chang, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Cloning of a heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) gene and expression analysis in the ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 32, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Yan, G.; Cheng, Y. Oxidative stress and genotoxic effect of deltamethrin exposure on the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 212, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thitamadee, S.; Prachumwat, A.; Srisala, J.; Jaroenlak, P.; Salachan, P.V.; Sritunyalucksana, K.; Flegel, T.W.; Itsathitphaisarn, O. Review of current disease threats for cultivated penaeid shrimp in Asia. Aquaculture 2016, 452, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Bacterial diseases of crabs: A review. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011, 106, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.; Nunan, L.; Redman, R.; Mohney, L.; Pantoja, C.; Fitzsimmons, K.; Lightner, D. Determination of the infectious nature of the agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome affecting penaeid shrimp. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2013, 105, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolowitz, R.M.; Bullis, R.A.; Abt, D.A. Pathologic Cuticular Changes of Winter Impoundment Shell Disease Preceding and During Intermolt in the American Lobster, Homarus americanus. Biol. Bull. 1992, 183, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogan, C.; Costa-Ramos, C.; Rowley, A. A histological study of shell disease syndrome in the edible crab Cancer pagurus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2001, 47, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.G.; Hu, S.Y.; Chiu, C.S.; Truong, Q.P.; Liu, C.H. Bacterial population in intestines of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei fed a synbiotic containing Lactobacillus plantarum and galactooligosaccharide. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, M.; Yuan, M.; Liu, M.; Gao, Q.; Wei, P.; Gu, W.; Wang, W.; Meng, Q. Characterization of cathepsin D from Eriocheir sinensis involved in Spiroplasma eriocheiris infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 86, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angthong, P.; Roytrakul, S.; Jarayabhand, P.; Jiravanichpaisal, P. Involvement of a tachylectin-like gene and its protein in pathogenesis of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in the shrimp, Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 76, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, N.; Todgham, A.; Ackerman, P.; Bibeau, M.; Nakano, K.; Schulte, P.; Iwama, G.K. Heat shock protein genes and their functional significance in fish. Gene 2002, 295, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, D.P.; Sinclair, A.F.; Hanson, J.M. Evolutionary response to size-selective mortality in an exploited fish population. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2007, 274, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, G.K.; Vijayan, M.M.; Forsyth, R.B.; Ackerman, P.A. Heat Shock Proteins and Physiological Stress in Fish. Am. Zool. 1999, 39, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Sharma, J.G.; Chakrabarti, R. Simulation study of natural UV-B radiation on Catla catla and its impact on physiology, oxidative stress, Hsp 70 and DNA fragmentation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2015, 149, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, B.P.; Banerjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mitra, T.; Purohit, G.K.; Sharma, A.P.; Karunakaran, D.; Mohanty, S. Muscle proteomics of the Indian major carp catla (Catla catla, Hamilton). J. Proteom. Bioinform. 2013, 6, 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, G.K.; Mahanty, A.; Suar, M.; Sharma, A.P.; Mohanty, B.P.; Mohanty, S. Investigating hsp gene expression in liver of Channa striataunder heat stress for understanding the upper thermal acclimation. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 381719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mohapatra, A.; Sahoo, P.K. Expression analysis of heat shock protein genes during Aeromonas hydrophila infection in rohu, Labeo rohita, with special reference to molecular characterization of Grp78. Cell Stress Chaperones 2015, 20, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, T.; Pal, A.K.; Chakraborty, S.K.; Manush, S.M.; Dalvi, R.S.; Apte, S.K.; Sahu, N.P.; Baruah, K. Biochemical and stress responses of rohu Labeo rohita and mrigal Cirrhinus mrigala in relation to acclimation temperatures. J. Fish Biol. 2009, 74, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elicker, K.S.; Hutson, L.D. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the small heat shock proteins in zebrafish. Gene 2007, 403, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, B.P.; Banerjee, S.; Sadhukhan, P.; Chowdhury, A.N.; Golder, D.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Bhowmick, S.; Manna, S.K.; Samanta, S. Pathophysiological Changes in Rohu (Labeo rohita, Hamilton) Fingerlings Following Arsenic Exposure. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2015, 38, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengkokpam, S.; Pal, A.; Sahu, N.; Jain, K.; Dalvi, R.; Misra, S.; Debnath, D. Metabolic modulation in Labeo rohita fingerlings during starvation: Hsp70 expression and oxygen consumption. Aquaculture 2008, 285, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, A.; Mohanty, S.; Mohanty, B.P. Dietary supplementation of curcumin augments heat stress tolerance through upregulation of nrf-2-mediated antioxidative enzymes and hsps in Pethia sophore. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, T.; Mahanty, A.; Ganguly, S.; Purohit, G.K.; Mohanty, S.; Parida, P.K.; Behera, P.R.; Raman, R.K.; Mohanty, B.P. Expression patterns of heat shock protein genes in Rita rita from natural riverine habitat as biomarker response against environmental pollution. Chemosphere 2018, 211, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia de la Serrana, D.; Johnston, I.A. Expression of heat shock protein (Hsp90) paralogues is regulated by amino acids in skeletal muscle of Atlantic salmon. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksala, N.K.; Ekmekçi, F.G.; Özsoy, E.; Kirankaya, S.; Kokkola, T.; Emecen, G.; Lappalainen, J.; Kaarniranta, K.; Atalay, M. Natural thermal adaptation increases heat shock protein levels and decreases oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2014, 3, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, T.F.; Inácio, A.; Coelho, M.M. Different levels of hsp70 and hsc70 mRNA expression in Iberian fish exposed to distinct river conditions. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2013, 36, 061–069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-L.; Yao, C.-L.; Wang, Z.-Y. Acute temperature and cadmium stress response characterization of small heat shock protein 27 in large yellow croaker, Larimichthys crocea. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 155, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perezcasanova, J.C.; Rise, M.L.; Dixon, B.; Afonso, L.O.B.; Hall, J.R.; Johnson, S.C.; Gamperl, A.K. The immune and stress responses of Atlantic cod to long-term increases in water temperature. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 24, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fangue, N.A.; Hofmeister, M.; Schulte, P.M. Intraspecific variation in thermal tolerance and heat shock protein gene expression in common killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 2859–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, H.; Watabe, S. Temperature-dependent enhancement of cell proliferation and mRNA expression for type I collagen and HSP70 in primary cultured goldfish cells. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2004, 138, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, N. A Drastic Reduction in the Basal Level of Heat-shock Protein 90 in the Brain of Goldfish (Carassius auratus) after Administration of Geldanamycin. Zool. Sci. 2004, 21, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.G.; Tufts, B.L. The physiological effects of heat stress and the role of heat shock proteins in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus f) red blood cells. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. Effect of heat stress on heat-shock protein (Hsp60) mRNA expression in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 5280–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendell, J.L.; Fowler, S.; Cockshutt, A.; Currie, S. Development-dependent differences in intracellular localization of stress proteins (hsps) in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, following heat shock. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2006, 1, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, I.; Linares-Casenave, J.; Van Eenennaam, J.P.; Doroshov, S.I. The Effect of Temperature Stress on Development and Heat-shock Protein Expression in Larval Green Sturgeon (Acipenser mirostris). Environ. Biol. Fishes 2007, 79, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Vega, E.; Hall, M.R.; Degnan, B.M.; Wilson, K.J. Short-term hyperthermic treatment of Penaeus monodon increases expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) and reduces replication of gill associated virus (GAV). Aquaculture 2006, 253, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.E.; Small, B.C.; Bosworth, B.G. Lipopolysaccharide regulates myostatin and MyoD independently of an increase in plasma cortisol in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005, 28, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Song, L.; Weng, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z. Hsp90, Hsp60 and sHsp families of heat shock protein genes in channel catfish and their expression after bacterial infections. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 44, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvakumar, S.; Geraldine, P. Heat shock protein induction in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium malcolmsonii: Acclimation-influenced variations in the induction temperatures for Hsp70. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2005, 140, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.M.; Briden, A.; Stokell, T.; Griffin, F.J.; Cherr, G.N. Thermotolerance and Hsp70 profiles in adult and embryonic California native oysters, Ostreola conchaphila (Carpenter, 1857). J. Shellfish Res. 2004, 23, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A.G.; Wuertz, S.; Mohammed-Geba, K. Lead-induced heat shock protein (HSP70) and metallothionein (MT) gene expression in the embryos of African catfish Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822). Sci. Afr. 2019, 3, e00056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothary, R.K.; Jones, D.; Candido, E.P. 70-Kilodalton heat shock polypeptides from rainbow trout: Characterization of cDNA sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1984, 4, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murtha, J.M.; Keller, E.T. Characterization of the heat shock response in mature zebrafish (Danio rerio). Exp. Gerontol. 2003, 38, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.G.; Yamamoto, Y.; Jeffery, W.R.; Krone, P.H. Zebrafish Hsp70 is required for embryonic lens formation. Cell Stress Chaperones 2005, 10, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherian, A.; Krone, P.H.; Ovsenek, N. A comparison of Hsp90 α and Hsp90 β interactions with cochaperones and substrates. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 86, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krone, P.; Sass, J. Hsp 90α and Hsp 90β Genes Are Present in the Zebrafish and Are Differentially Regulated in Developing Embryos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 204, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Ye, X.; Zou, S.; Lu, M.; Liu, Z.; Tian, Y. Characterization of four heat-shock protein genes from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and demonstration of the inducible transcriptional activity of Hsp70 promoter. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 40, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, L.; Lanubile, R.; Tarantino, P.; Mandich, A.; Cataldi, E. Expression of stress proteins 70 in tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) during confinement and crowding stress. Ital. J. Zool. 2006, 73, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, A.N.; Ghaida’a Jassim, A.; Al-Niaeem, K.S. Comet and Micronucleus Assays for Detecting Benzo (a) Pyrene Genotoxicity in Blood Cells of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) from the Shatt Al-Arab River in Southern Iraq. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, A.; Biemar, F.; Müller, F.; Iyengar, A.; Prunet, P.; Maclean, N.; Martial, J.A.; Muller, M. Cloning and expression analysis of an inducibleHSP70gene from tilapia fish. FEBS Lett. 2000, 474, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuanazzi, J.S.G.; De Lara, J.A.F.; Goes, E.S.D.R.; Almeida, F.L.A.; De Oliveira, C.A.L.; Ribeiro, R.P. Anoxia stress and effect on flesh quality and gene expression of tilapia. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tine, M.; Bonhomme, F.; McKenzie, D.J.; Durand, J.-D. Differential expression of the heat shock protein Hsp70 in natural populations of the tilapia, Sarotherodon melanotheron, acclimatised to a range of environmental salinities. BMC Ecol. 2010, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zhang, G.; Yin, S.; Wang, L. The role of three heat shock protein genes in the immune response to Aeromonas hydrophila challenge in marbled eel, Anguilla marmorata. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y. Responses of HSP gene expressions to elevated water temperature in the Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Dev. Reprod. 2010, 14, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Xu, T. A heat shock protein 90 β isoform involved in immune response to bacteria challenge and heat shock from Miichthys miiuy. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Q.; Fei, F.; Huang, B.; Meng, X.S.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, K.F.; Chen, H.-B.; Xing, R.; Liu, B.L. Alterations in hematological and biochemical parameters, oxidative stress, and immune response in Takifugu rubripes under acute ammonia exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 243, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karouna-Renier, N.K.; Zehr, J.P. Short-term exposures to chronically toxic copper concentrations induce HSP70 proteins in midge larvae (Chironomus tentans). Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 312, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Luan, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Xiang, J. Cloning of cytoplasmic heat shock protein 90 (FcHSP90) from Fenneropenaeus chinensis and its expression response to heat shock and hypoxia. Cell Stress Chaperones 2009, 14, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, A.N.; Winton, J.R.; Dickhoff, W.W. Tissue-Specific Induction of Hsp90 mRNA and Plasma Cortisol Response in Chinook Salmon following Heat Shock, Seawater Challenge, and Handling Challenge. Mar. Biotechnol. 2000, 2, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, G.; Buckley, B.; Airaksinen, S.; Keen, J.; Somero, G. Heat-shock protein expression is absent in the antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii (family Nototheniidae). J. Exp. Biol. 2000, 203, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S.D.; Dickson, K.L.; Zimmerman, E.G.; Sanders, B.M. Tissue-specific patterns of synthesis of heat-shock proteins and thermal tolerance of the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Can. J. Zool. 1991, 69, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebaugh, D.R.; Wallace, W.G. Assimilation and subcellular partitioning of elements by grass shrimp collected along an impact gradient. Aquat. Toxicol. 2009, 93, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarate, J.; Bradley, T.M. Heat shock proteins are not sensitive indicators of hatchery stress in salmon. Aquaculture 2003, 223, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, R.B.; Candido, E.P.M.; Babich, S.L.; Iwama, G.K. Stress Protein Expression in Coho Salmon with Bacterial Kidney Disease. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1997, 9, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, P.A.; Iwama, G.K. Physiological and Cellular Stress Responses of Juvenile Rainbow Trout to Vibriosis. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2001, 13, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, E.E.; Woo, N.Y.S. Evidence for disruption of Na+-K+-ATPase and hsp70 during vibriosis of sea bream, Sparus (= Rhabdosargus) sarba Forsskål. J. Fish Dis. 2005, 28, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.Y.; Van Damme, E.J.; Sorgeloos, P.; Bossier, P. Non-lethal heat shock protects gnotobiotic Artemia franciscana larvae against virulent Vibrios. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007, 22, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.-Y.; Kang, S.-T.; Chen, W.-Y.; Hsu, T.-C.; Lo, C.-F.; Liu, K.-F.; Chen, L.-L. Identification of the small heat shock protein, HSP21, of shrimp Penaeus monodon and the gene expression of HSP21 is inactivated after white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, V.; Miquel, A.; Burzio, L.O.; Rosemblatt, M.; Engel, E.; Valenzuela, S.; Parada, G.; Valenzuela, P.D. A vaccine against the salmonid pathogen Piscirickettsia salmonis based on recombinant proteins. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5083–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, K.P.; LaPatra, S.E.; Cain, K.D. Vaccination of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), with recombinant and DNA vaccines produced to Flavobacterium psychrophilum heat shock proteins 60 and 70. J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryckaert, J.; Pasmans, F.; Tobback, E.; Duchateau, L.; Decostere, A.; Haesebrouck, F.; Sorgeloos, P.; Bossier, P. Heat shock proteins protect platyfish (Xiphophorus maculatus) from Yersinia ruckeri induced mortality. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 28, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falfushynska, H.I.; Phan, T.; Sokolova, I.M. Long-Term Acclimation to Different Thermal Regimes Affects Molecular Responses to Heat Stress in a Freshwater Clam Corbicula Fluminea. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, V.A.; Peck, L.S.; Dyrynda, E.A.; Smith, V.J.; Clark, M.S. Cellular stress responses to chronic heat shock and shell damage in temperate Mya truncata. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsakiozi, P.; Parmakelis, A.; Aggeli, I.-K.; Gaitanaki, C.; Giokas, S.; Valakos, E.D. Water balance and expression of heat-shock protein 70 in Codringtonia species: A study within a phylogenetic framework. J. Molluscan Stud. 2015, 81, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanina, A.V.; Cherkasov, A.S.; Sokolova, I.M. Effects of cadmium on cellular protein and glutathione synthesis and expression of stress proteins in eastern oysters, Crassostrea virginica Gmelin. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 211, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Pan, H.; Pan, B.; Bu, W. Identification and functional characterization of three TLR signaling pathway genes in Cyclina sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 50, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Kim, P.-J.; Dahms, H.-U.; Han, K.-N. Bio-effect-monitoring of long-term thermal wastes on the oyster, Crassostrea gigas, using heat shock proteins. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-M. Expression profiles of heat shock protein gene families in the monogonont rotifer Brachionus koreanus—Exposed to copper and cadmium. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcy, E.; Serpentini, A.; Fiévet, B.; Lebel, J.-M. Identification of cDNAs encoding HSP70 and HSP90 in the abalone Haliotis tuberculata: Transcriptional induction in response to thermal stress in hemocyte primary culture. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 146, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissiéres, A.; Mitchell, H.K.; Tracy, U.M. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: Relation to chromosome puffs. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 84, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, S. Regulation of protein synthesis during heat shock. Nature 1981, 293, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhotia, S.C. Forty years of the 93D puff of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biosci. 2011, 36, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathasivam, R.; Ki, J.-S. Heat shock protein genes in the green alga Tetraselmis suecica and their role against redox and non-redox active metals. Eur. J. Protistol. 2019, 69, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Folgar, R.; Martínez-Guitarte, J.-L. Cadmium alters the expression of small heat shock protein genes in the aquatic midge Chironomus riparius. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Paz, P.; Morales, M.; Martín, R.; Martínez-Guitarte, J.L.; Morcillo, G. Characterization of the small heat shock protein Hsp27 gene in Chironomus riparius (Diptera) and its expression profile in response to temperature changes and xenobiotic exposures. Cell Stress Chaperones 2014, 19, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Lei, C.; Zhu, F. Starvation-, thermal- and heavy metal- associated expression of four small heat shock protein genes in Musca domestica. Gene 2018, 642, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærsgaard, A.; Blanckenhorn, W.U.; Pertoldi, C.; Loeschcke, V.; Kaufmann, C.; Hald, B.; Pagès, N.; Bahrndorff, S. Plasticity in behavioural responses and resistance to temperature stress in Musca domestica. Anim. Behav. 2015, 99, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Ren, G.; Huang, D.; Liu, F. Stress-induced HSP70 from Musca domestica plays a functionally significant role in the immune system. J. Insect Physiol. 2012, 58, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Rohilla, M.S.; Tiwari, P.K. Developmental and hyperthermia-induced expression of the heat shock proteins HSP60 and HSP70 in tissues of the housefly Musca domestica: An in vitro study. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinet, H.; Hance, T. Male Reproductive Potential of Aphidius colemani (Hymenoptera: Aphidiinae) Exposed to Constant or Fluctuating Thermal Regimens. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, K.; Kotsiliti, E.; Mintzas, A.C. Stage and cell-specific expression and intracellular localization of the small heat shock protein Hsp27 during oogenesis and spermatogenesis in the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 96, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yocum, G.D.; Joplin, K.H.; Denlinger, D.L. Upregulation of a 23 kDa small heat shock protein transcript during pupal diapause in the flesh fly, Sarcophaga crassipalpis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 28, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.-H.; Hou, Q.-L. Identification and expression analysis of cuticular protein genes in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 178, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrońska, A.K.; Boguś, M.I. Heat shock proteins (HSP 90, 70, 60, and 27) in Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera) hemolymph are affected by infection with Conidiobolus coronatus (Entomophthorales). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivam, S.; Ertl, R.; Sexl, V.; El-Matbouli, M.; Kumar, G. Differentially expressed transcripts of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Cnidaria) between carrier and dead-end hosts involved in key biological processes: Novel insights from a coupled approach of FACS and RNA sequencing. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engman, D.M.; Dragon, E.A.; Donelson, J.E. Human humoral immunity to hsp70 during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 1990, 144, 3987–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedstrom, R.; Culpepper, J.; Schinski, V.; Agabian, N.; Newport, G. Schistosome heat-shock proteins are immunologically distinct host-like antigens. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1988, 29, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]