Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: From Cause to Therapy

Abstract

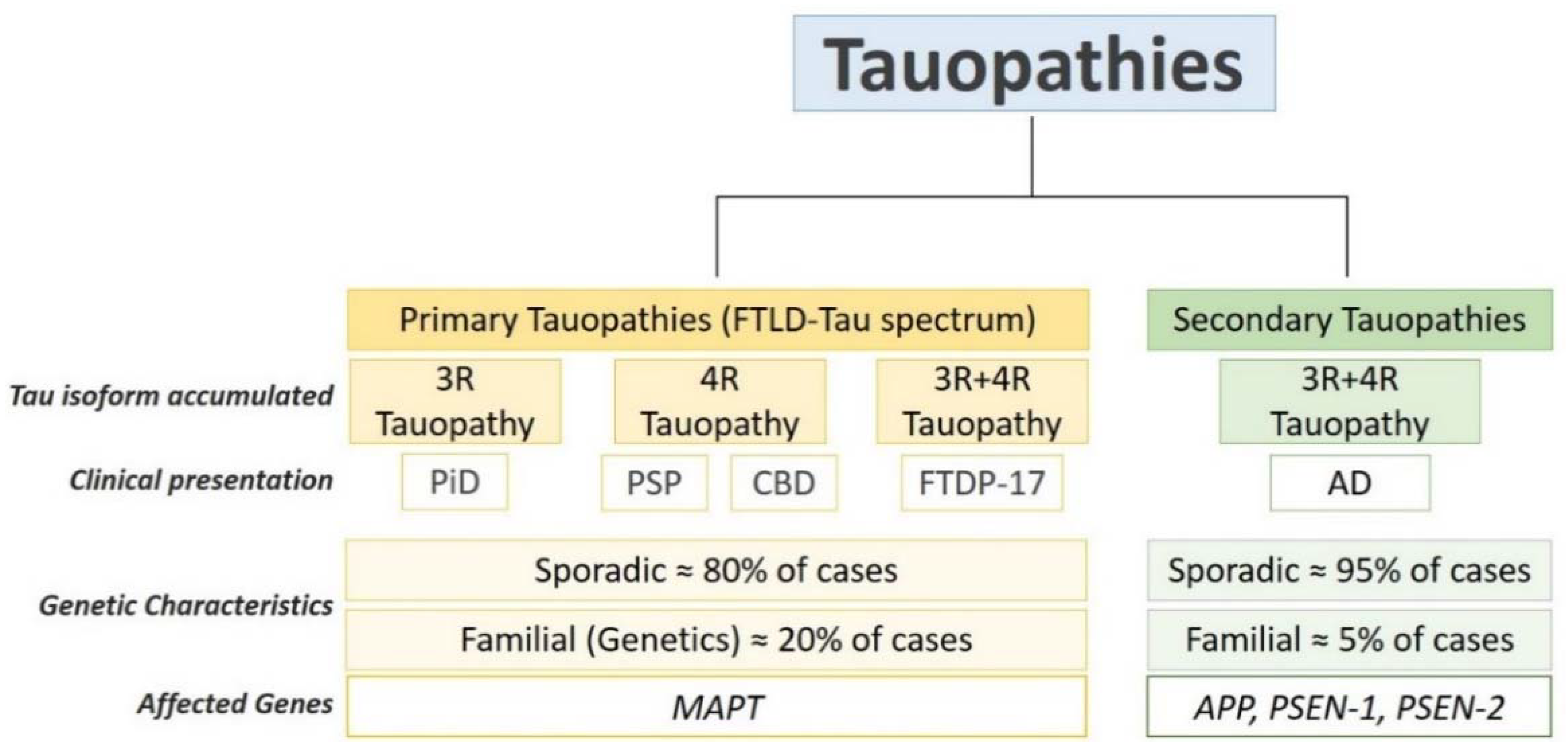

1. Introduction: Oxidative Stress and Tauopathies

2. Molecular Mechanisms Leading to Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: Implication of Mitochondria and Antioxidant Enzymes

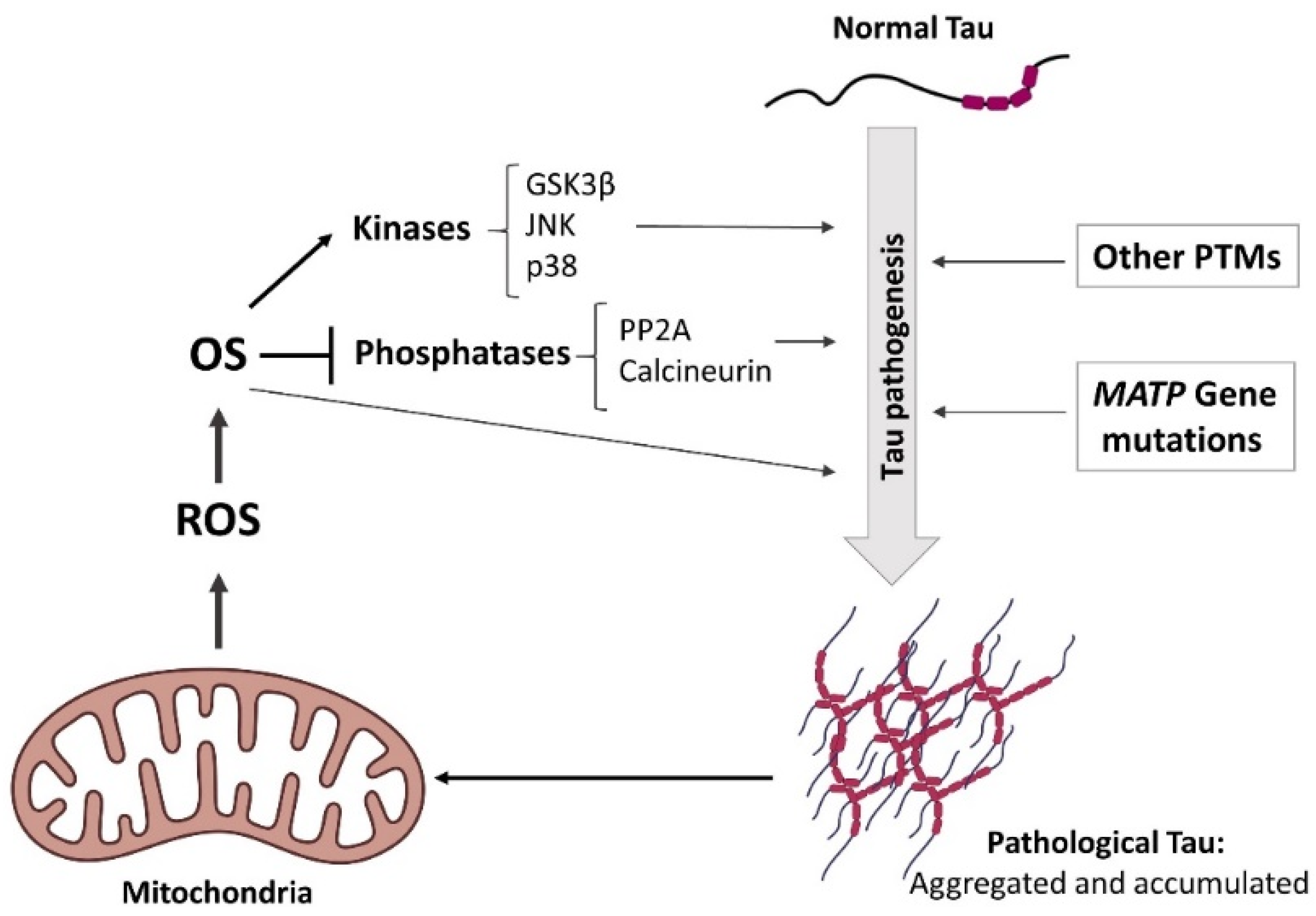

3. Oxidative Stress and Tau Pathogenesis: Cause or Consequence?

3.1. Tau Pathogenesis as a Consequence of Oxidative Stress

3.2. Pathological Tau as Oxidative Stress Inductor

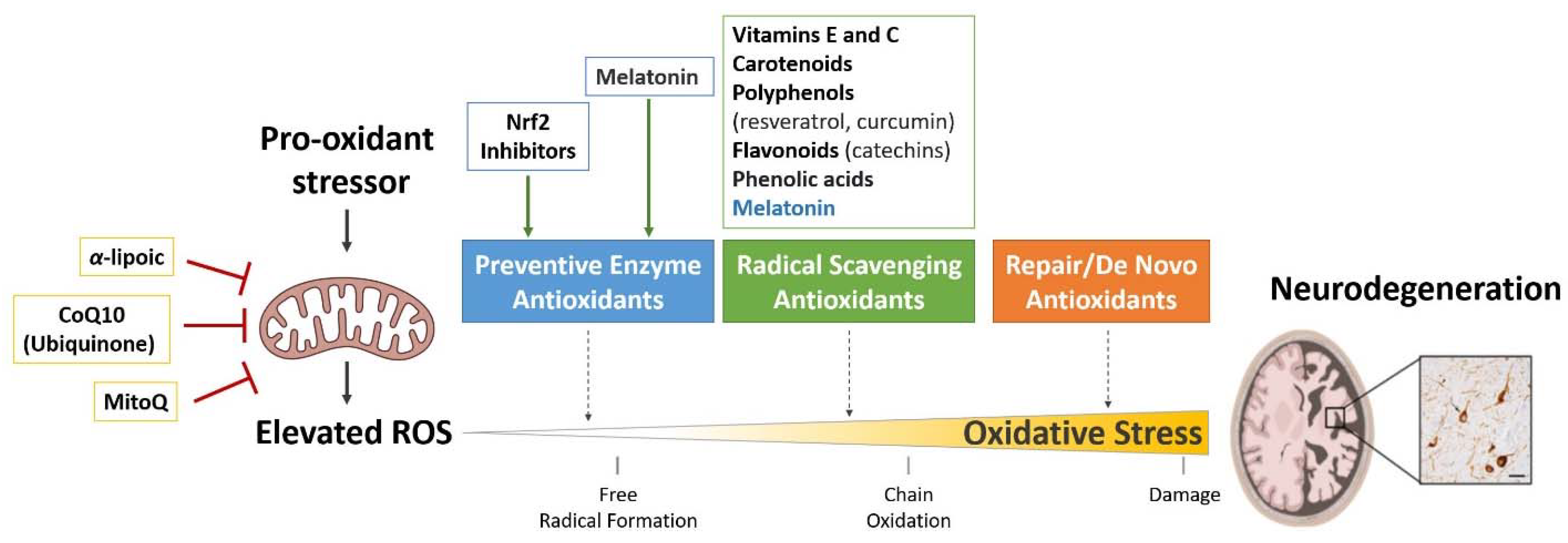

4. Antioxidant Therapies for the Treatment of Tauopathies

4.1. Treatments Targeting Antioxidant Enzymes

4.2. Free Radical Scavengers

4.3. Treatments Targeting Mitochondria

5. Present and Future of Antioxidant Therapies

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D.; Affourtit, C.; Esteves, T.C.; Green, K.; Lambert, A.J.; Miwa, S.; Pakay, J.L.; Parker, N. Mitochondrial superoxide: Production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W. Free Radicals in the Physiological Control of Cell Function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auten, R.L.; Davis, J.M. Oxygen Toxicity and Reactive Oxygen Species: The Devil Is in the Details. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-Y.; Lee, T.-H. Antioxidant enzymes as redox-based biomarkers: A brief review. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Witkowska, A.M.; Zujko, M.E. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Adv. Med. Sci. 2018, 63, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, T.; Stieler, J.T.; Holzer, M. Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 126, 238–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ture, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.-E.C.; Roemer, S.; Petrucelli, L.; Dickson, D.W. Cellular and pathological heterogeneity of primary tauopathies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alquezar, C.; Schoch, K.M.; Geier, E.G.; Ramos, E.M.; Scrivo, A.; Li, K.H.; Argouarch, A.R.; Mlynarski, E.E.; Dombroski, B.; De Ture, M.; et al. TSC1 loss increases risk for tauopathy by inducing tau acetylation and preventing tau clearance via chaperone-mediated autophagy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, G.G. Tauopathies. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 145, pp. 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, S. Oxidative Stress and the Central Nervous System. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 360, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. The economy of brain network organization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.S.; Hardingham, G.E. Adaptive regulation of the brain’s antioxidant defences by neurons and astrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, V.; Lazzarino, G.; Amorini, A.M.; Tavazzi, B.; D’Urso, S.; Longo, S.; Vagnozzi, R.; Signoretti, S.; Clementi, E.; Giardina, B.; et al. Neuroglobin expression and oxidant/antioxidant balance after graded traumatic brain injury in the rat. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 69, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerstein, D.; Backes, H.; Gramer, M.; Takagaki, M.; Gabel, P.; Kumagai, T.; Graf, R. Regulation of cerebral metabolism during cortical spreading depression. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016, 36, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, R.; Smith, M.; Richey, P.; Kalaria, R.; Gambetti, P.; Perry, G. Evidence for oxidative stress in Pick disease and corticobasal degeneration. Brain Res. 1995, 696, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.; Stack, C.; Elipenahli, C.; Jainuddin, S.; Gerges, M.; Starkova, N.N.; Yang, L.; Starkov, A.A.; Beal, F. Behavioral deficit, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction precede tau pathology in P301S transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 4063–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.; Carmona, M.; Portero-Otin, M.; Naudí, A.; Pamplona, R.; Ferrer, I. Type-Dependent Oxidative Damage in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Cortical Astrocytes Are Targets of Oxidative Damage. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 67, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvan, I. Update on progressive supranuclear palsy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2004, 4, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odetti, P.; Garibaldi, S.; Norese, R.; Angelini, G.; Marinelli, L.; Valentini, S.; Menini, S.; Traverso, N.; Zaccheo, D.; Siedlak, S.; et al. Lipoperoxidation Is Selectively Involved in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 59, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Albers, D.S.; Augood, S.J.; Martin, D.M.; Standaert, D.G.; Vonsattel, J.P.G.; Beal, M.F. Evidence for Oxidative Stress in the Subthalamic Nucleus in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. J. Neurochem. 1999, 73, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, I.; Keller-McGandy, C.E.; Albers, D.S.; Beal, M.F.; Vonsattel, J.-P.; Standaert, D.G.; Augood, S.J. Expression and activity of antioxidants in the brain in progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain Res. 2002, 930, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K.; Matsubara, K.; Kobayashi, S. Aging and oxidative stress in progressive supranuclear palsy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunomura, A.; Castellani, R.J.; Zhu, X.; Moreira, P.I.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojsiat, J.; Zoltowska, K.M.; Laskowska-Kaszub, K.; Wojda, U. Oxidant/Antioxidant Imbalance in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic and Diagnostic Prospects. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6435861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, C. Alzheimer’s disease and oxidative stress: Implications for novel therapeutic approaches. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999, 57, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.; Chauhan, A. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Pathophysiology 2006, 13, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M. Alzheimer´s Disease and Oxidative Stress: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-González, E.; Henares-Chavarino, Á.A.; Pedrero-Prieto, C.M.; García-Carpintero, S.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Sancho-Bielsa, F.J.; Alcain, F.J.; Peinado, J.R.; Rabanal-Ruíz, Y.; Durán-Prado, M. Interplay Between Mitochondrial Oxidative Disorders and Proteostasis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Vasciaveo, V.; Tabaton, M. Oxidative Stress and Beta Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease. Which Comes First: The Chicken or the Egg? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, R.; Hirai, K.; Aliev, G.; Drew, K.L.; Nunomura, A.; Takeda, A.; Cash, A.D.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 70, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Ma, X.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteras, N.; Rohrer, J.; Hardy, J.; Wray, S.; Abramov, A.Y. Mitochondrial hyperpolarization in iPSC-derived neurons from patients of FTDP-17 with 10+16 MAPT mutation leads to oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, D.S.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurochem. Int. 2002, 40, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, M.F. Mitochondria, free radicals, and neurodegeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996, 6, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, K.; Aliev, G.; Nunomura, A.; Fujioka, H.; Russell, R.L.; Atwood, C.S.; Johnson, A.B.; Kress, Y.; Vinters, H.V.; Tabaton, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Abnormalities in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 3017–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Aliev, G. Mitochondrial failures in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2004, 19, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein, V.; Song, X.; Wiesner, A.; Ittner, L.M.; Baysang, G.; Meier, F.; Ozmen, L.; Bluethmann, H.; Dröse, S.; Brandt, U.; et al. Amyloid-β and tau synergistically impair the oxidative phosphorylation system in triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20057–20062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Irwin, R.W.; Zhao, L.; Nilsen, J.; Hamilton, R.T.; Brinton, R.D. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14670–14675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ittner, L.M.; Fath, T.; Ke, Y.D.; Bi, M.; van Eersel, J.; Li, K.M.; Gunning, P.; Götz, J. Parkinsonism and impaired axonal transport in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15997–16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeikina, K.J.; Carlson, G.A.; Pitstick, R.; Ludvigson, A.E.; Peters, A.; Luebke, J.I.; Koffie, R.M.; Frosch, M.P.; Hyman, B.T.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Tau Accumulation Causes Mitochondrial Distribution Deficits in Neurons in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy and in Human Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, T.; Pooler, A.M.; Lau, D.H.; Mórotz, G.M.; De Vos, K.J.; Gilley, J.; Coleman, M.P.; Hanger, D.P. Reduced number of axonal mitochondria and tau hypophosphorylation in mouse P301L tau knockin neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, N.; Tweedie, A.; Zuryn, S.; Bertran-Gonzalez, J.; Götz, J. Disease-associated tau impairs mitophagy by inhibiting Parkin translocation to mitochondria. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e99360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, D.; Hauptmann, S.; Scherping, I.; Schuessel, K.; Keil, U.; Rizzu, P.; Ravid, R.; Dröse, S.; Brandt, U.; Müller, W.E.; et al. Proteomic and Functional Analyses Reveal a Mitochondrial Dysfunction in P301L Tau Transgenic Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 23802–23814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, X.-C.; Wang, Z.-H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.-P.; Feng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yue, Z.; Chen, Z.; et al. Tau accumulation impairs mitophagy via increasing mitochondrial membrane potential and reducing mitochondrial Parkin. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 17356–17368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.-P.; Feng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Ye, K.; Liu, G.-P.; et al. Human wild-type full-length tau accumulation disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and the functions via increasing mitofusins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, T.E.; Madero-Pérez, J.; Swaney, D.L.; Chang, T.S.; Moritz, M.; Konrad, C.; Ward, M.E.; Stevenson, E.; Hüttenhain, R.; Kauwe, G.; et al. Tau interactome maps synaptic and mitochondrial processes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell 2022, 185, 712–728.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBoff, B.; Götz, J.; Feany, M.B. Tau Promotes Neurodegeneration via DRP1 Mislocalization In Vivo. Neuron 2012, 75, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, M.; Chaudhury, P.; Kabiru, H.; Shea, T.B. Tau inhibits anterograde axonal transport and perturbs stability in growing axonal neurites in part by displacing kinesin cargo: Neurofilaments attenuate tau-mediated neurite instability. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2008, 65, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, A.; Nisbet, R.; Grimm, A.; Götz, J. March separate, strike together—Role of phosphorylated TAU in mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamer, K.; Vogel, R.; Thies, E.; Mandelkow, E.; Mandelkow, E.-M. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 156, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.D.; Kaech, S.; Banker, G. Selective Microtubule-Based Transport of Dendritic Membrane Proteins Arises in Concert with Axon Specification. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 4135–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, T.F.; Petrucelli, L. The role of tau in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, R.; Manczak, M.; Yin, X.; Wang, R.; Reddy, P.H. Hippocampal phosphorylated tau induced cognitive decline, dendritic spine loss and mitochondrial abnormalities in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 27, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.L.; Eckert, A.; Rhein, V.; Mai, S.; Haase, W.; Reichert, A.S.; Jendrach, M.; Müller, W.E.; Leuner, K. A New Link to Mitochondrial Impairment in Tauopathies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.; Biliouris, E.E.; Lang, U.E.; Götz, J.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G.; Eckert, A. Sex hormone-related neurosteroids differentially rescue bioenergetic deficits induced by amyloid-β or hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-L.; Wang, H.-H.; Liu, S.-J.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Tian, Q.; Wang, X.-C.; Chen, X.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.-Y.; et al. Phosphorylation of tau antagonizes apoptosis by stabilizing β-catenin, a mechanism involved in Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3591–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, C.; Aránguiz, A.; Cerpa, W.; Tapia-Rojas, C.; Quintanilla, R.A. Genetic ablation of tau improves mitochondrial function and cognitive abilities in the hippocampus. Redox Biol. 2018, 18, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.P.; Corbett, N.J.; Kellett, K.A.B.; Hooper, N.M. Tau Proteolysis in the Pathogenesis of Tauopathies: Neurotoxic Fragments and Novel Biomarkers. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 63, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlante, A.; Amadoro, G.; Bobba, A.; de Bari, L.; Corsetti, V.; Pappalardo, G.; Marra, E.; Calissano, P.; Passarella, S. A peptide containing residues 26–44 of tau protein impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation acting at the level of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1777, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadoro, G.; Corsetti, V.; Atlante, A.; Florenzano, F.; Capsoni, S.; Bussani, R.; Mercanti, D.; Calissano, P. Interaction between NH(2)-Tau Fragment and Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease mitochondria contributes to the synaptic deterioration. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 33, 833.e1–833.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, R.A.; von Bernhardi, R.; Godoy, J.A.; Inestrosa, N.C.; Johnson, G.V.W. Phosphorylated tau potentiates Aβ-induced mitochondrial damage in mature neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 71, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunomura, A.; Perry, G.; Aliev, G.; Hirai, K.; Takeda, A.; Balraj, E.K.; Jones, P.K.; Ghanbari, H.; Wataya, T.; Shimohama, S.; et al. Oxidative Damage Is the Earliest Event in Alzheimer Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 60, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Kornatowski, M.; Krzywińska, O.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Changes in the blood antioxidant defense of advanced age people. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybka, J.; Kupczyk, D.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K.; Pawluk, H.; Czuczejko, J.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Antonioli, M.; Carvalho, L.A.; Kędziora, J. Age-related changes in an antioxidant defense system in elderly patients with essential hypertension compared with healthy controls. Redox Rep. 2011, 16, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriollo-Sanchez, M.; Hininger-Favier, I.; Meunier, N.; Venneria, E.; O’Connor, J.M.; Maiani, G.; Coudray, C.; Roussel, A.M. Age-related oxidative stress and antioxidant parameters in middle-aged and older European subjects: The ZENITH study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, S58–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D.L.; Thomas, C.; Rodriguez, C.; Simberkoff, K.; Tsai, J.S.; Strafaci, J.A.; Freedman, M.L. Increased Peroxidation and Reduced Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 150, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, A.; Marcatti, M.; Zolochevska, O.; Tabor, N.; Woltjer, R.; Moreno, S.; Taglialatela, G. Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Response in Frontal Cortex of Demented and Nondemented Individuals with Alzheimer’s Neuropathology. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melov, S.; Adlard, P.A.; Morten, K.; Johnson, F.; Golden, T.R.; Hinerfeld, D.; Schilling, B.; Mavros, C.; Masters, C.L.; Volitakis, I.; et al. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Causes Hyperphosphorylation of Tau. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Santagata, D.; Fulga, T.A.; Duttaroy, A.; Feany, M.B. Oxidative stress mediates tau-induced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, A.W.P.; Falcon, B.; He, S.; Murzin, A.G.; Murshudov, G.; Garringer, H.J.; Crowther, R.A.; Ghetti, B.; Goedert, M.; Scheres, S.H.W. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2017, 547, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakhamia, T.; Lee, C.E.; Carlomagno, Y.; Duong, D.M.; Kundinger, S.R.; Wang, K.; Williams, D.; De Ture, M.; Dickson, D.W.; Cook, C.N.; et al. Posttranslational Modifications Mediate the Structural Diversity of Tauopathy Strains. Cell 2020, 180, 633–644.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, B.; Noad, J.; McMahon, H.; Randow, F.; Goedert, M. Galectin-8–mediated selective autophagy protects against seeded tau aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, B.; Zivanov, J.; Zhang, W.; Murzin, A.G.; Garringer, H.J.; Vidal, R.; Crowther, R.A.; Newell, K.L.; Ghetti, B.; Goedert, M.; et al. Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Nature 2019, 568, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragón-Rodríguez, S.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X.; Moreira, P.; Acevedo-Aquino, M.C.; Williams, S. Phosphorylation of Tau Protein as the Link between Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Connectivity Failure: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 940603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi Naini, S.M.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N. Tau hyperphosphorylation and oxidative stress, a critical vicious circle in neurodegenerative tauopathies? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 151979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Li, P.; Wei, N.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, H.; Ji, X.; Chen, W.; Xue, M.; Wei, J. The Ambiguous Relationship of Oxidative Stress, Tau Hyperphosphorylation, and Autophagy Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 352723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, W.-H.; Zhao, J.-S.; Meng, F.-Z.; Wang, H. Lutein protects against β-amyloid peptide-induced oxidative stress in cerebrovascular endothelial cells through modulation of Nrf-2 and NF-κb. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2017, 33, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquezar, C.; Arya, S.; Kao, A.W. Tau Post-translational Modifications: Dynamic Transformers of Tau Function, Degradation, and Aggregation. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 595532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finelli, M.J. Redox Post-translational Modifications of Protein Thiols in Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Conditions—Focus on S-Nitrosation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, W.; Weisbach, V.; Sticht, H.; Seebahn, A.; Bussmann, J.; Zimmermann, R.; Becker, C.-M. Oxidative stress-induced posttranslational modifications of human hemoglobin in erythrocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 529, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.D.C.; Zaidi, T.; Novak, M.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Hyperphosphorylation induces self-assembly of τ into tangles of paired helical filaments/straight filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6923–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.-M. The Development of Cell Processes Induced by tau Protein Requires Phosphorylation of Serine 262 and 356 in the Repeat Domain and Is Inhibited by Phosphorylation in the Proline-rich Domains. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, G.; Trinczek, B.; Illenberger, S.; Biernat, J.; Schmitt-Ulms, G.; Meyer, H.E.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Microtubule-Associated Protein/Microtubule Affinity-Regulating Kinase (P110(Mark)). A Novel Protein Kinase That Regulates Tau-Microtubule Interactions and Dynamic Instability by Phosphorylation at the Alzheimer- Specific Site Serine 262. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 7679–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, J.; Gustke, N.; Drewes, G.; Mandelkow, E. Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: Distinction between PHF-like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron 1993, 11, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Chan, C. Palmitic and stearic fatty acids induce Alzheimer-like hyperphosphorylation of tau in primary rat cortical neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 384, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wang, X.; Lee, H.G.; Tabaton, M.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Zhu, X. Chronic oxidative stress causes increased tau phosphorylation in M17 neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 468, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Salazar, A.; Bañuelos-Hernandez, B.; Rodriguez-Leyva, I.; Chi-Ahumada, E.; Monreal-Escalante, E.; Jiménez-Capdeville, M.E.; Rosales-Mendoza, S. Oxidative Stress Modifies the Levels and Phosphorylation State of Tau Protein in Human Fibroblasts. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Jakes, R.; Lawler, S.; Cuenda, A.; Cohen, P. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by stress-activated protein kinases. FEBS Lett. 1997, 409, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, C.; Ghetti, B.; Piva, R.; Srinivasan, A.N.; Zolo, P.; Delisle, M.B.; Mirra, S.S.; Migheli, A. Activation of the JNK/p38 Pathway Occurs in Diseases Characterized by Tau Protein Pathology and Is Related to Tau Phosphorylation But Not to Apoptosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 60, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Parola, M.; Bardini, P.; Piccini, A.; Borghi, R.; Guglielmotto, M.; Santoro, G.; Davit, A.; Danni, O.; Smith, M.A.; et al. β-Site APP cleaving enzyme up-regulation induced by 4-hydroxynonenal is mediated by stress-activated protein kinases pathways. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgenaidi, I.S.; Spiers, J.P. Regulation of the phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A system and its modulation during oxidative stress: A potential therapeutic target? Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 198, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, M.A.; Xiong, S.; Xie, C.; Davies, P.; Markesbery, W.R. Induction of hyperphosphorylated tau in primary rat cortical neuron cultures mediated by oxidative stress and glycogen synthase kinase-3. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2004, 6, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yu, G.; Shu, X.; Ge, H.; Zeng, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Cleavage of GSK-3β by calpain counteracts the inhibitory effect of Ser9 phosphorylation on GSK-3β activity induced by H2O2. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, A.; Badia, M.-C.; Giraldo, E.; Ermak, G.; Alonso, M.-D.; Pallardó, F.V.; Davies, K.J.A.; Viña, J. Amyloid-β Toxicity and Tau Hyperphosphorylation are Linked Via RCAN1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 27, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Koh, S.-H.; Noh, M.Y.; Park, K.-W.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β activity plays very important roles in determining the fate of oxidative stress-inflicted neuronal cells. Brain Res. 2007, 1129, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-W.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, M.-S. Oxidative stress with tau hyperphosphorylation in memory impaired 1,2-diacetylbenzene-treated mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 279, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, E.; Lloret, A.; Fuchsberger, T.; Vina, J. Aβ and tau toxicities in Alzheimer’s are linked via oxidative stress-induced p38 activation: Protective role of vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Huang, S. Cadmium activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway via induction of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of protein phosphatases 2A and 5. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Choi, J.-E.; Chang, E.-J.; Yoon, S.Y. Increased phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 and mitochondrial fission in okadaic acid-treated neurons. Brain Res. 2012, 1454, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppek, D.; Keck, S.; Ermak, G.; Jung, T.; Stolzing, A.; Ullrich, O.; Davies, K.J.A.; Grune, T. Phosphorylation inhibits turnover of the tau protein by the proteasome: Influence of RCAN1 and oxidative stress. Biochem. J. 2006, 400, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano, C.A.; Egaña, J.T.; Núñez, M.T.; Maccioni, R.B.; González-Billault, C. Oxidative Stress Promotes Tau Dephosphorylation in Neuronal Cells: The Roles of Cdk5 and PP1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamblin, T.C.; King, M.E.; Kuret, J.; Berry, R.W.; Binder, L.I. Oxidative Regulation of Fatty Acid-Induced Tau Polymerization. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 14203–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Cuadros, R.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Avila, J. Phosphorylated, but not native, tau protein assembles following reaction with the lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Smith, M.A.; Avilá, J.; DeBernardis, J.; Kansal, M.; Takeda, A.; Zhu, X.; Nunomura, A.; Honda, K.; Moreira, P.; et al. Alzheimer-specific epitopes of tau represent lipid peroxidation-induced conformations. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ramos, A.; Diaz-Nido, J.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Avila, J. Effect of the lipid peroxidation product acrolein on tau phosphorylation in neural cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 71, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Boyd-Kimball, D.; Poon, H.F.; Cai, J.; Pierce, W.M.; Klein, J.B.; Markesbery, W.R.; Zhou, X.Z.; Lu, K.P.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative modification and down-regulation of Pin1 in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus: A redox proteomics analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, M.; Dourlen, P.; Bretteville, A.; Sambo, A.-V.; Ferreira, S.; Ando, K.; Kerdraon, O.; Bégard, S.; Geay, L.; Lippens, G.; et al. Pin1 allows for differential Tau dephosphorylation in neuronal cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006, 32, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Tsutsumi, K.; Taoka, M.; Saito, T.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Ishiguro, K.; Plattner, F.; Uchida, T.; Isobe, T.; Hasegawa, M.; et al. Isomerase Pin1 Stimulates Dephosphorylation of Tau Protein at Cyclin-dependent Kinase (Cdk5)-dependent Alzheimer Phosphorylation Sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 7968–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-H.; Li, W.; Sultana, R.; You, M.-H.; Kondo, A.; Shahpasand, K.; Kim, B.M.; Luo, M.-L.; Nechama, M.; Lin, Y.-M.; et al. Pin1 cysteine-113 oxidation inhibits its catalytic activity and cellular function in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 76, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsholme, P.; Keane, K.N.; Carlessi, R.; Cruzat, V. Oxidative stress pathways in pancreatic β-cells and insulin-sensitive cells and tissues: Importance to cell metabolism, function, and dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C420–C433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.A.; Wijesekara, N.; Fraser, P.E.; De Felice, F.G. The Link Between Tau and Insulin Signaling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, S.; Ahn, D.U. Protein Oxidation: Basic Principles and Implications for Meat Quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweers, O.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E. Oxidation of cysteine-322 in the repeat domain of microtubule-associated protein tau controls the in vitro assembly of paired helical filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 8463–8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, B.; Wang, Y.; Diaz, A.; Tasset, I.; Juste, Y.R.; Stiller, B.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E.; Cuervo, A.M. Interplay of pathogenic forms of human tau with different autophagic pathways. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteras, N.; Kundel, F.; Amodeo, G.F.; Pavlov, E.V.; Klenerman, D.; Abramov, A.Y. Insoluble tau aggregates induce neuronal death through modification of membrane ion conductance, activation of voltage-gated calcium channels and NADPH oxidase. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, H.; Ikezu, S.; Tsunoda, S.; Medalla, M.; Luebke, J.; Haydar, T.; Wolozin, B.; Butovsky, O.; Kügler, S.; Ikezu, T. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolós, M.; Llorens-Martín, M.; Jurado-Arjona, J.; Hernández, F.; Rábano, A.; Avila, J. Direct Evidence of Internalization of Tau by Microglia In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 50, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasulo, L.; Visintin, M.; Novak, M.; Cattaneo, A. Tau Truncation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Expression of a Fragment Encompassing PHF Core. Alzheimers Rep. 1998, 1, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.L.; Garcia-Sierra, F.; Reynolds, M.R.; Horowitz, P.M.; Fu, Y.; Wang, T.; Cahill, M.E.; Bigio, E.H.; Berry, R.W.; Binder, L.I. Tau truncation during neurofibrillary tangle evolution in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paholikova, K.; Salingova, B.; Opattova, A.; Skrabana, R.; Majerova, P.; Zilka, N.; Kovacech, B.; Zilkova, M.; Barath, P.; Novak, M. N-terminal Truncation of Microtubule Associated Protein Tau Dysregulates its Cellular Localization. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 43, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cente, M.; Filipcik, P.; Mandakova, S.; Zilka, N.; Krajciova, G.; Novak, M. Expression of a Truncated Human Tau Protein Induces Aqueous-Phase Free Radicals in a Rat Model of Tauopathy: Implications for Targeted Antioxidative Therapy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 17, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.-Y.; Wu, W.-H.; Huang, Z.-P.; Hu, J.; Lei, P.; Yu, C.-H.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Li, Y.-M. Hydrogen peroxide can be generated by tau in the presence of Cu(II). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 358, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Bai, F. The Association of Tau With Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, H.; Modi, J.P.; Wu, J.-Y. Mechanisms of Neuronal Protection against Excitotoxicity, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Stroke and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, e964518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.; Silva, T.; Andrade, P.B.; Borges, F. Alzheimer’s Disease and Antioxidant Therapy: How Long How Far? Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 2939–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, V.; Rogelj, B.; Župunski, V. Therapeutic Potential of Polyphenols in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Zulueta, M.; Ensz, L.M.; Mukhina, G.; Lebovitz, R.M.; Zwacka, R.M.; Engelhardt, J.F.; Oberley, L.W.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Protects nNOS Neurons from NMDA and Nitric Oxide-Mediated Neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 2040–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Huang, H.C.; Pickett, C.B. Transcriptional Regulation of the Antioxidant Response Element. Activation by Nrf2 and Repression by MafK. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15466–15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf2 signaling in coordinated activation of antioxidant gene expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapias, V.; Jainuddin, S.; Ahuja, M.; Stack, C.; Elipenahli, C.; Vignisse, J.; Gerges, M.; Starkova, N.; Xu, H.; Starkov, A.A.; et al. Benfotiamine treatment activates the Nrf2/ARE pathway and is neuroprotective in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2874–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, C.; Jainuddin, S.; Elipenahli, C.; Gerges, M.; Starkova, N.; Starkov, A.A.; Jové, M.; Portero-Otin, M.; Launay, N.; Pujol, A.; et al. Methylene blue upregulates Nrf2/ARE genes and prevents tau-related neurotoxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3716–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Kügler, S.; Lastres-Becker, I. Pharmacological targeting of GSK-3 and NRF2 provides neuroprotection in a preclinical model of tauopathy. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, G.; Jo, D.-G. Therapeutic Approaches to Alzheimer’s Disease through Modulation of NRF2. Neuromol. Mol. Med. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, S. Metabolic Effects of Melatonin on Oxidative Stress and Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine 2005, 27, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J.; Manchester, L.C.; Yan, M.-T.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardelan, R. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin: A well-documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Terron, M.P.; Flores, L.J.; Reiter, R.J. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J. Pineal Res. 2007, 42, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Qi, W. Biochemical Reactivity of Melatonin with Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: A Review of the Evidence. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 34, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin as a natural ally against oxidative stress: A physicochemical examination. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, D.; Reiter, R.J.; Calvo, J.R.; Guerrero, J.M. Physiological concentrations of melatonin inhibit nitric oxide synthase in rat cerebellum. Life Sci. 1994, 55, PL455–PL460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, D.; Reiter, R.J.; Calvo, J.R.; Guerrero, J.M. Inhibition of cerebellar nitric oxide synthase and cyclic GMP production by melatonin via complex formation with calmodulin. J. Cell. Biochem. 1997, 65, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Balmik, A.A.; Chinnathambi, S. Melatonin Reduces GSK3β-Mediated Tau Phosphorylation, Enhances Nrf2 Nuclear Translocation and Anti-Inflammation. ASN Neuro 2020, 12, 1759091420981204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-C.; Wang, Z.-F.; Zhang, J.-X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.-Z. Effect of melatonin on calyculin A-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 510, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-Q.; Xu, G.; Duan, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.-Z. Effects of melatonin on wortmannin-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-L.; Ling, Z.-Q.; Cao, F.-Y.; Zhu, L.-Q.; Wang, J.-Z. Melatonin attenuates isoproterenol-induced protein kinase A overactivation and tau hyperphosphorylation in rat brain. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 37, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Stahl, W. Vitamins E and C, beta-carotene, and other carotenoids as antioxidants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 62, 1315S–1321S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, H.; Ishihara, T.; Yokota, O.; Terada, S.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Kuroda, S. Effects of α-tocopherol on an animal model of tauopathies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devore, E.E.; Grodstein, F.; Van Rooij, F.J.; Hofman, A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Witteman, J.C.; Breteler, M.M. Dietary Antioxidants and Long-term Risk of Dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.; Yao, Y.; Uryu, K.; Yang, H.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Praticò, D. Early Vitamin E supplementation in young but not aged mice reduces Aβ levels and amyloid deposition in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2003, 18, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, M.; Ernesto, C.; Thomas, R.G.; Klauber, M.R.; Schafer, K.; Grundman, M.; Woodbury, P.; Growdon, J.; Cotman, C.W.; Pfeiffer, E.; et al. A Controlled Trial of Selegiline, Alpha-Tocopherol, or Both as Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlik, V.N.; Doody, R.S.; Rountree, S.D.; Darby, E.J. Vitamin E Use Is Associated with Improved Survival in an Alzheimer’s Disease Cohort. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2010, 28, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Sun, Q.; Chen, S. Oxidative stress: A major pathogenesis and potential therapeutic target of antioxidative agents in Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016, 147, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, A.; Badía, M.-C.; Mora, N.J.; Pallardó, F.V.; Alonso, M.-D.; Viña, J. Vitamin E Paradox in Alzheimer’s Disease: It Does Not Prevent Loss of Cognition and May Even Be Detrimental. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 17, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Bei, R.; Mistretta, A.; Marventano, S.; Calabrese, G.; Masuelli, L.; Giganti, M.G.; Modesti, A.; Galvano, F.; Gazzolo, D. Effects of Vitamin C on Health: A Review of Evidence. Front. Biosci. 2013, 18, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, T.L.; Lunec, J. ReviewPart of the Series: From Dietary Antioxidants to Regulators in Cellular Signalling and Gene ExpressionReview: When Is an Antioxidant Not an Antioxidant? A Review of Novel Actions and Reactions of Vitamin C. Free. Radic. Res. 2005, 39, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.E. A Critical Review of Vitamin C for the Prevention of Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 29, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacelli, F.; Acquarone, E.; Giannotti, C.; Borghi, R.; Nencioni, A. Vitamin C, Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kook, S.-Y.; Lee, K.-M.; Kim, Y.; Cha, M.-Y.; Kang, S.; Baik, S.H.; Lee, H.; Park, R.; Mook-Jung, I. High-dose of vitamin C supplementation reduces amyloid plaque burden and ameliorates pathological changes in the brain of 5XFAD mice. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.-M. The Possible Role of Antioxidant Vitamin C in Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment and Prevention. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2013, 28, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Murata, N.; Ozawa, Y.; Kinoshita, N.; Irie, K.; Shirasawa, T.; Shimizu, T. Vitamin C Restores Behavioral Deficits and Amyloid-β Oligomerization without Affecting Plaque Formation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 26, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, S.; Müller-Thomsen, T.; Beisiegel, U.; Kontush, A. Effect of One-Year Vitamin C- and E-Supplementation on Cerebrospinal Fluid Oxidation Parameters and Clinical Course in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 2706–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasko, D.R.; Peskind, E.; Clark, C.M.; Quinn, J.F.; Ringman, J.M.; Jicha, G.A.; Cotman, C.; Cottrell, B.; Montine, T.J.; Thomas, R.G.; et al. Antioxidants for Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upritchard, J.E.; Schuurman, C.R.; Wiersma, A.; Tijburg, L.B.; Coolen, S.A.; Rijken, P.J.; Wiseman, S.A. Spread supplemented with moderate doses of vitamin E and carotenoids reduces lipid peroxidation in healthy, nonsmoking adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhir, R.; Mehrotra, A.; Kamboj, S.S. Lycopene prevents 3-nitropropionic acid-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunctions in nervous system. Neurochem. Int. 2010, 57, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, A.K.; Chopra, K. Lycopene abrogates Aβ(1–42)-mediated neuroinflammatory cascade in an experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Jiang, Z.; Liao, Y.; Song, Z.; Nan, X. Lycopene Prevents Amyloid [Beta]-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Dysfunctions in Cultured Rat Cortical Neurons. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, B.F.; Veloso, C.A.; Nogueira-Machado, J.A.; de Moraes, E.N.; dos Santos, R.R.; Cintra, M.T.G.; Chaves, M.M. Ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol, and beta-carotene reduce oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines in mononuclear cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Nutr. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, C.D.; Gadal, S.; Mhatre, M.; Williamson, K.S.; Pye, Q.N.; Hensley, K. Antioxidants in Central Nervous System Diseases: Preclinical Promise and Translational Challenges. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2008, 15, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivarelli, F.; Canistro, D.; Cirillo, S.; Papi, A.; Spisni, E.; Vornoli, A.; Croce, C.M.D.; Longo, V.; Franchi, P.; Filippi, S.; et al. Co-carcinogenic effects of vitamin E in prostate. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.R.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Dalal, D.; Riemersma, R.A.; Appel, L.J.; Guallar, E. Meta-Analysis: High-Dosage Vitamin E Supplementation May Increase All-Cause Mortality. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G.; Nikolova, D.; Gluud, L.L.; Simonetti, R.G.; Gluud, C. Mortality in Randomized Trials of Antioxidant Supplements for Primary and Secondary Prevention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007, 297, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Kasum, C.M. DIETARY FLAVONOIDS: Bioavailability, Metabolic Effects, and Safety. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swallah, M.S.; Sun, H.; Affoh, R.; Fu, H.; Yu, H. Antioxidant Potential Overviews of Secondary Metabolites (Polyphenols) in Fruits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 9081686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-Y.; Dong, Q.-X.; Zhu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, L.-F.; Qiu, M.; Yu, X.-L.; Liu, R.-T. Resveratrol Rescues Tau-Induced Cognitive Deficits and Neuropathology in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Najafi, M.; Samarghandian, S.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Ahn, K.S. Resveratrol targeting tau proteins, amyloid-beta aggregations, and their adverse effects: An updated review. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2867–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosín-Tomàs, M.; Senserrich, J.; Arumí-Planas, M.; Alquézar, C.; Pallàs, M.; Martín-Requero, Á.; Suñol, C.; Kaliman, P.; Sanfeliu, C. Role of Resveratrol and Selenium on Oxidative Stress and Expression of Antioxidant and Anti-Aging Genes in Immortalized Lymphocytes from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griñán-Ferré, C.; Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Izquierdo, V.; Corpas, R.; Roig-Soriano, J.; Chillón, M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Somogyvári, M.; Sőti, C.; Sanfeliu, C.; et al. The pleiotropic neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease pathology: From antioxidant to epigenetic therapy. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarroca, S.; Gatius, A.; Rodríguez-Farré, E.; Vilchez, D.; Pallàs, M.; Griñán-Ferré, C.; Sanfeliu, C.; Corpas, R. Resveratrol confers neuroprotection against high-fat diet in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via modulation of proteolytic mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 89, 108569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Resveratrol: A review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellone, E.; Galtieri, A.; Russo, A.; Giardina, B.; Ficarra, S. Resveratrol: A Focus on Several Neurodegenerative Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 392169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaramaiah, K.; Chung, W.J.; Michaluart, P.; Telang, N.; Tanabe, T.; Inoue, H.; Jang, M.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Dannenberg, A.J. Resveratrol Inhibits Cyclooxygenase-2 Transcription and Activity in Phorbol Ester-treated Human Mammary Epithelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21875–21882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecave, M.; Lepoivre, M.; Elleingand, E.; Gerez, C.; Guittet, O. Resveratrol, a remarkable inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase. FEBS Lett. 1998, 421, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.R.; Ward, N.E.; Ioannides, C.G.; O’Brian, C.A. Resveratrol Preferentially Inhibits Protein Kinase C-Catalyzed Phosphorylation of a Cofactor-Independent, Arginine-Rich Protein Substrate by a Novel Mechanism. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 13244–13251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.A.; Savio, M.; Forti, L.; Shevelev, I.; Ramadan, K.; Stivala, L.A.; Vannini, V.; Hübscher, U.; Spadari, S.; Maga, G. Inhibition of mammalian DNA polymerases by resveratrol: Mechanism and structural determinants. Biochem. J. 2005, 389, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basly, J.-P.; Marre-Fournier, F.; Le Bail, J.-C.; Habrioux, G.; Chulia, A.J. Estrogenic/antiestrogenic and scavenging properties of (E)- and (Z)-resveratrol. Life Sci. 2000, 66, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marumo, M.; Ekawa, K.; Wakabayashi, I. Resveratrol inhibits Ca2+ signals and aggregation of platelets. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Chen, L.; Xiao, F.; Sun, H.; Ding, H.; Xiao, H. Resveratrol improves non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Wang, M.; Qiu, X.; Liu, D.; Jiang, H.; Yang, N.; Xu, R.-M. Structural basis for allosteric, substrate-dependent stimulation of SIRT1 activity by resveratrol. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-W.; Cho, S.-H.; Zhou, Y.; Schroeder, S.; Haroutunian, V.; Seeley, W.W.; Huang, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Masliah, E.; Mukherjee, C.; et al. Acetylation of Tau Inhibits Its Degradation and Contributes to Tauopathy. Neuron 2010, 67, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Stankowski, J.N.; Carlomagno, Y.; Stetler, C.; Petrucelli, L. Acetylation: A new key to unlock tau’s role in neurodegeneration. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-W.; Chen, X.; Tracy, T.E.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Shirakawa, K.; Minami, S.S.; Defensor, E.; Mok, S.-A.; et al. Critical role of acetylation in tau-mediated neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.; Cohen, T.J.; Grossman, M.; Arnold, S.E.; McCarty-Wood, E.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Acetylated Tau Neuropathology in Sporadic and Hereditary Tauopathies. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 183, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-W.; Sohn, P.D.; Li, Y.; Devidze, N.; Johnson, J.R.; Krogan, N.J.; Masliah, E.; Mok, S.-A.; Gestwicki, J.E.; Gan, L. SIRT1 Deacetylates Tau and Reduces Pathogenic Tau Spread in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 3680–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, S.; Matthes, F.; Posey, K.; Kickstein, E.; Weber, S.; Hettich, M.M.; Pfurtscheller, S.; Ehninger, D.; Schneider, R.; Krauß, S. Resveratrol induces dephosphorylation of Tau by interfering with the MID1-PP2A complex. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Scott, E.; Brown, V.A.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P.; Brown, K. Clinical trials of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.S.; Thomas, R.G.; Craft, S.; Van Dyck, C.H.; Mintzer, J.; Reynolds, B.A.; Brewer, J.B.; Rissman, R.A.; Raman, R.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2015, 85, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, C.; Hebron, M.; Huang, X.; Ahn, J.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflam. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawda, C.; Moussa, C.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol for Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1403, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Maiti, P.; Ma, Q.; Zuo, X.; Jones, M.R.; Cole, G.M.; Frautschy, S.A. Clinical development of curcumin in neurodegenerative disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanantharajah, L.; Mudher, A. Curcumin as a Holistic Treatment for Tau Pathology. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 903119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, J.S.; Bhaumik, P.; Panda, D. Curcumin Inhibits Tau Aggregation and Disintegrates Preformed Tau Filaments in vitro. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 60, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, F.L.; Puangmalai, N.; Ellsworth, A.; Bucchieri, F.; Pace, A.; Piccionello, A.P.; Kayed, R. Toxic Tau Oligomers Modulated by Novel Curcumin Derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Haan, J.; Morrema, T.H.J.; Rozemuller, A.J.; Bouwman, F.H.; Hoozemans, J.J.M. Different curcumin forms selectively bind fibrillar amyloid beta in post mortem Alzheimer’s disease brains: Implications for in-vivo diagnostics. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Xie, C.; Yoshimura, S.; Shinzaki, Y.; Yoshina, S.; Kage-Nakadai, E.; Mitani, S.; Ihara, Y. Curcumin improves tau-induced neuronal dysfunction of nematodes. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 39, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagl, S.; Kocher, A.; Schiborr, C.; Kolesova, N.; Frank, J.; Eckert, G.P. Curcumin micelles improve mitochondrial function in neuronal PC12 cells and brains of NMRI mice—Impact on bioavailability. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, J.R.; Poore, C.P.; Sulaimee, N.H.B.; Pareek, T.; Cheong, W.F.; Wenk, M.R.; Pant, H.C.; Frautschy, S.A.; Low, C.-M.; Kesavapany, S. Curcumin Ameliorates Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Memory Deficits in p25 Transgenic Mouse Model that Bears Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 60, 1429–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, N.; He, H.; Tang, X. Pharmaceutical strategies of improving oral systemic bioavailability of curcumin for clinical application. J. Control. Release 2019, 316, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaropoulou, S.D.; Van Amelsvoort, T.A.M.J.; Prickaerts, J.; Vingerhoets, C. The effect of curcumin on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease and healthy aging: A systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies. Brain Res. 2019, 1725, 146476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Manach, C.; Rémésy, C. Absorption and metabolism of polyphenols in the gut and impact on health. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Jiménez, D.; Corella-Salazar, D.A.; Zuñiga-Martínez, B.S.; Domínguez-Avila, J.A.; Montiel-Herrera, M.; Salazar-López, N.J.; Rodrigo-Garcia, J.; Villegas-Ochoa, M.A.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Phenolic compounds that cross the blood–brain barrier exert positive health effects as central nervous system antioxidants. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10356–10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, N.; Fernando, W.B.; Hone, E.; Sohrabi, H.R.; Johnson, S.K.; Gunzburg, S.; Martins, R.N. Potential of Sorghum Polyphenols to Prevent and Treat Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review Article. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwajgier, D.; Borowiec, K.; Pustelniak, K. The Neuroprotective Effects of Phenolic Acids: Molecular Mechanism of Action. Nutrients 2017, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Luo, G.; Li, L.; Le, W. Neuroprotective Effects of (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 31, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.; Wang, G.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Su, Q.; Jiang, J.; Du, Y. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on iron metabolism in spinal cord motor neurons. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, E.; Rajasekaran, R. Probing the inhibitory activity of epigallocatechin-gallate on toxic aggregates of mutant (L84F) SOD1 protein through geometry based sampling and steered molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2017, 74, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, S.; Suzuki, N.; Masuda, M.; Hisanaga, S.-I.; Iwatsubo, T.; Goedert, M.; Hasegawa, M. Inhibition of Heparin-induced Tau Filament Formation by Phenothiazines, Polyphenols, and Porphyrins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 7614–7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, H.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, K.-H.; Yu, H.-J.; Do, B.R.; Kim, K.S.; Jung, H.K. Phosphatidylinositol-3 Kinase/Akt and GSK-3 Mediated Cytoprotective Effect of Epigallocatechin Gallate on Oxidative Stress-Injured Neuronal-Differentiated N18D3 Cells. NeuroToxicology 2004, 25, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Johnson, G.V.W. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β Phosphorylates Tau at Both Primed and Unprimed Sites: Differential Impact on Microtubule Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.; Che, Z. Ameliorating effect of luteolin on memory impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4215–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rahul; Jyoti, S.; Naz, F.; Ashafaq, M.; Shahid, M.; Siddique, Y.H. Therapeutic potential of luteolin in transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 692, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assogna, M.; Casula, E.P.; Borghi, I.; Bonnì, S.; Samà, D.; Motta, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; D’Acunto, A.; Porrazzini, F.; Minei, M.; et al. Effects of Palmitoylethanolamide Combined with Luteoline on Frontal Lobe Functions, High Frequency Oscillations, and GABAergic Transmission in Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.M.; Surette, M.; Bercik, P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lukiw, W. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Microbiome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.; Mulak, A. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 25, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R.P.; Chapman, M.R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.M.; Mercante, J.W.; Neish, A.S. Reactive Oxygen Production Induced by the Gut Microbiota: Pharmacotherapeutic Implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N.; Fiorello, M.L.; Bailey, D.M. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siedlak, S.L.; Casadesus, G.; Webber, K.M.; Pappolla, M.A.; Atwood, C.S.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G. Chronic antioxidant therapy reduces oxidative stress in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Res. 2009, 43, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Wang, D.-W.; Xu, S.-F.; Zhang, S.; Fan, Y.-G.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Guo, S.-Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, T.; Wang, Z.-Y.; et al. α-Lipoic acid improves abnormal behavior by mitigation of oxidative stress, inflammation, ferroptosis, and tauopathy in P301S Tau transgenic mice. Redox Biol. 2017, 14, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarini-Gakiye, E.; Vaezi, G.; Parivar, K.; Sanadgol, N. Age and Dose-Dependent Effects of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Human Microtubule- Associated Protein Tau-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Unfolded Protein Response: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 20, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.; Bussiere, J.R.; Hammond, R.S.; Montine, T.J.; Henson, E.; Jones, R.E.; Stackman, R.W. Chronic dietary α-lipoic acid reduces deficits in hippocampal memory of aged Tg2576 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2007, 28, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonakdar, R.A.; Guarneri, E. Coenzyme Q10. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 72, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, M.; Kipiani, K.; Yu, F.; Wille, E.; Katz, M.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Gouras, G.K.; Lin, M.T.; Beal, M.F. Coenzyme Q10 Decreases Amyloid Pathology and Improves Behavior in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 27, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elipenahli, C.; Stack, C.; Jainuddin, S.; Gerges, M.; Yang, L.; Starkov, A.; Beal, M.F.; Dumont, M. Behavioral Improvement after Chronic Administration of Coenzyme Q10 in P301S Transgenic Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 28, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Lian, N.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, K.; Yu, Y. Coenzyme Q10 alleviates sevoflurane-induced neuroinflammation by regulating the levels of apolipoprotein E and phosphorylated tau protein in mouse hippocampal neurons. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, K.L.; Shefner, J.; Zhang, H.; Betensky, R.; O’Brien, M.; Yu, H.; Fantasia, M.; Taft, J.; Beal, M.F.; Traynor, B.; et al. Tolerance of high-dose (3,000 mg/day) coenzyme Q10 in ALS. Neurology 2005, 65, 1834–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamelou, M.; Reuss, A.; Pilatus, U.; Magerkurth, J.; Niklowitz, P.; Eggert, K.M.; Krisp, A.; Menke, T.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Oertel, W.H.; et al. Short-term effects of coenzyme Q10 in progressive supranuclear palsy: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Marıa, I.; Santpere, G.; MacDonald, M.J.; de Barreda, E.G.; Hernandez, F.; Moreno, F.J.; Ferrer, I.; Avila, J. Coenzyme Q Induces Tau Aggregation, Tau Filaments, and Hirano Bodies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 67, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelso, G.F.; Porteous, C.M.; Coulter, C.V.; Hughes, G.; Porteous, W.K.; Ledgerwood, E.C.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P. Selective Targeting of a Redox-active Ubiquinone to Mitochondria within Cells: Antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 4588–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.L.; Franklin, J.L. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ inhibits memory loss, neuropathology, and extends lifespan in aged 3xTg-AD mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 101, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteras, N.; Kopach, O.; Maiolino, M.; Lariccia, V.; Amoroso, S.; Qamar, S.; Wray, S.; Rusakov, D.A.; Jaganjac, M.; Abramov, A.Y. Mitochondrial ROS control neuronal excitability and cell fate in frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourashed, E.A. Bioavailability of Plant-Derived Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiserman, A.; Koliada, A.; Zayachkivska, A.; Lushchak, O. Nanodelivery of Natural Antioxidants: An Anti-aging Perspective. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamishehkar, H.; Ranjdoost, F.; Asgharian, P.; Mahmoodpoor, A.; Sanaie, S. Vitamins, Are They Safe? Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Ziegler, A.C.; Dimitrion, P.; Zuo, L. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, e2525967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilgun-Sherki, Y.; Melamed, E.; Offen, D. Oxidative stress induced-neurodegenerative diseases: The need for antioxidants that penetrate the blood brain barrier. Neuropharmacology 2001, 40, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.; Benfeito, S.; Fernandes, C.; Borges, F. Chapter 9—Antioxidant Therapy, Oxidative Stress, and Blood-Brain Barrier: The Road of Dietary Antioxidants. In Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases; Martin, C.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 125–141. ISBN 978-0-12-817780-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T.M.; Golde, T.E.; Lagier-Tourenne, C. Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.S.; Williams, L.A.; Eggan, K.C. Constructing and Deconstructing Stem Cell Models of Neurological Disease. Neuron 2011, 70, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.; Arzua, T.; Canfield, S.G.; Seminary, E.R.; Sison, S.L.; Ebert, A.D.; Bai, X. Studying Human Neurological Disorders Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From 2D Monolayer to 3D Organoid and Blood Brain Barrier Models. Compr. Physiol. 2019, 9, 565–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartolome, F.; Carro, E.; Alquezar, C. Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: From Cause to Therapy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081421

Bartolome F, Carro E, Alquezar C. Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: From Cause to Therapy. Antioxidants. 2022; 11(8):1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081421

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartolome, Fernando, Eva Carro, and Carolina Alquezar. 2022. "Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: From Cause to Therapy" Antioxidants 11, no. 8: 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081421

APA StyleBartolome, F., Carro, E., & Alquezar, C. (2022). Oxidative Stress in Tauopathies: From Cause to Therapy. Antioxidants, 11(8), 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081421