Fisetin Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via the Inhibition of YAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Culture of Human Chorion-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

2.2. Immunophenotypic Characterization

2.3. Culture of the Osteosarcoma Cell Line (SAOS-2)

2.4. Fisetin Preparation

2.5. Fisetin Toxicity Test

2.6. Osteogenic Differentiation and Mineralization Assay

2.7. Alizarin Red S Quantification

2.8. Alkaline Phosphatase Staining

2.9. Wound Healing Assay

2.10. Transwell Migration Assay

2.11. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (Real-Time qRT-PCR)

2.12. Western Blot Analysis

2.13. Computational Method

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fisetin Suppresses MSC Proliferation and Migration in a Dose-Dependent Manner

3.2. Fisetin Inhibits the Expressions of Toll-Like Receptors and YAP Protein

3.3. MSCs Failed to Undergo Osteogenic Differentiation upon Fisetin Treatment

3.4. Fisetin Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration, and Maturation of Osteoblast-Like Cells

3.5. Targeting YAP in Osteoblast-Like Cells Recapitulates Fisetin-Induced Phenotypes

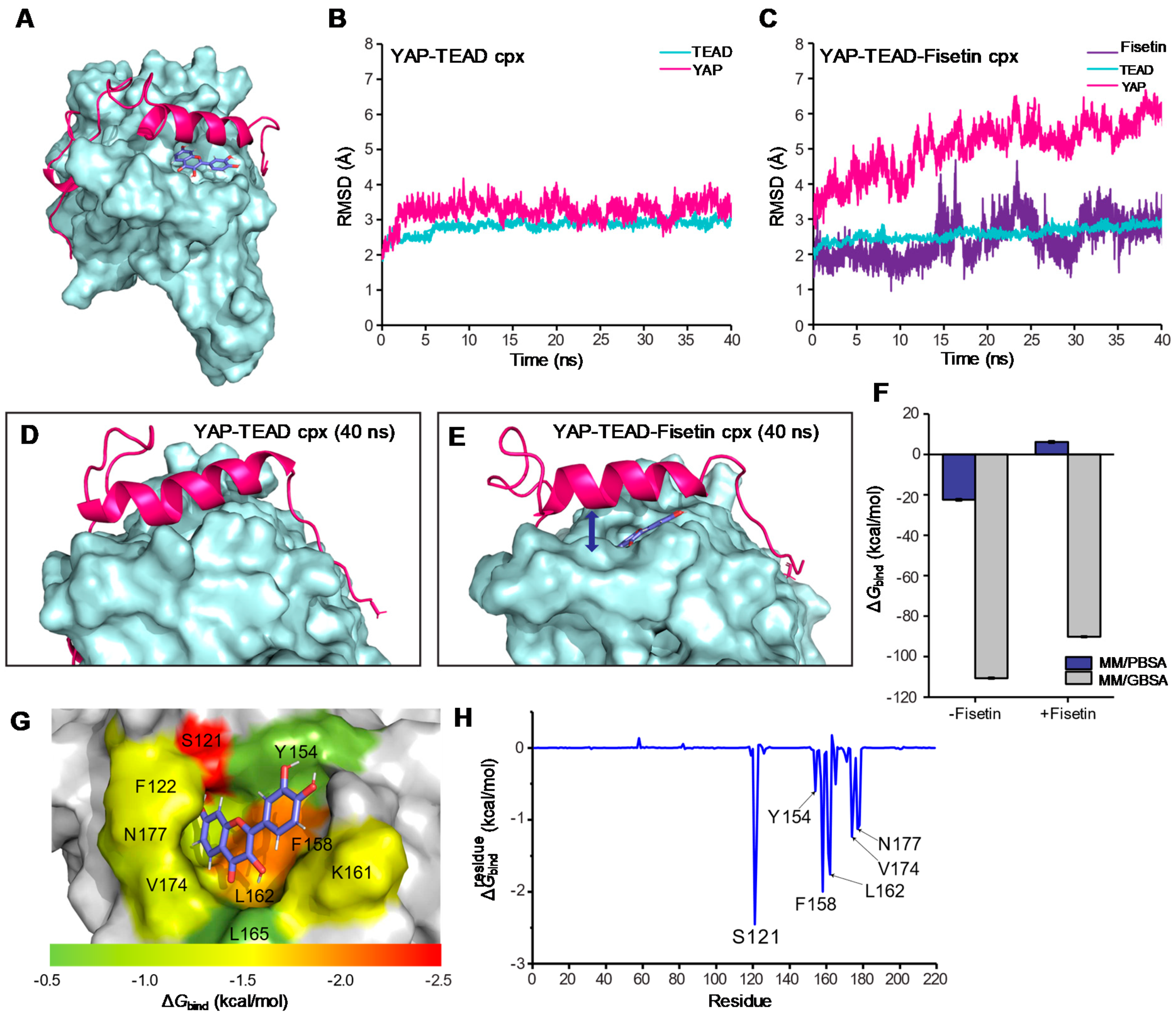

3.6. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamic Simulation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

Abbreviations

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| YAP-KD | YAP knock-down |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| shRNA | Short hairpin RNA |

| PBS | Phosphate buffer saline |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FCS | Fetal Calf Serum |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene difluoride |

| COL1A1 | Collagen type 1 |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| FAP | Fibroblast activation protein |

| VIM | Vimentin |

References

- Jash, S.K.; Mondal, S. Bioactive flavonoid fisetin–A molecule of pharmacological interest. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap, D.; Garg, V.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Yerer, M.B.; Sak, K.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Aggarwal, V.; Sandhu, S.S. Fisetin and Quercetin: Promising Flavonoids with Chemopreventive Potential. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, P. Modulation of the Neuroprotective and Anti-inflammatory Activities of the Flavonol Fisetin by the Transition Metals Iron and Copper. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Ma, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Yu, M.; Cao, K.; Yang, L.; Yang, G.; et al. Anticancer effects of fisetin on mammary carcinoma cells via regulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: In vitro and in vivo studies. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haddad, A.Q.; Venkateswaran, V.; Viswanathan, L.; Teahan, S.J.; Fleshner, N.E.; Klotz, L.H. Novel antiproliferative flavonoids induce cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005, 9, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimira, M.; Arai, Y.; Shimoi, K.; Watanabe, S. Japanese Intake of Flavonoids and Isoflavonoids from Foods. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 8, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, H.D.; Sohn, U.D.; La, H.O. Endothelium-Independent Effect of Fisetin on the Agonist-Induced Regulation of Vascular Contractility. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liou, C.J.; Wei, C.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Huang, W.C. Fisetin Protects Against Hepatic Steatosis Through Regulation of the Sirt1/AMPK and Fatty Acid be-ta-Oxidation Signaling Pathway in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-M.; Li, W.-Y.; Huang, M.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Q. Fisetin, a dietary flavonoid induces apoptosis via modulating the MAPK and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways in human osteosarcoma (U-2 OS) cells. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2015, 10, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Syed, D.N.; Mukhtar, H. Fisetin, a novel dietary flavonoid, causes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Kang, J.H.; Yun, M.; Lee, S.B. Quercetin inhibits the poly (dA:dT)-induced secretion of IL-18 via down-regulation of the expressions of AIM2 and pro-caspase-1 by inhibiting the JAK2/STAT1 pathway in IFN-γ-primed human keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Ye, T.; Xiang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lou, B.; Zhang, F.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. Quercetin inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition, decreases invasiveness and metastasis, and reverses IL-6 induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition, expression of MMP by inhibiting STAT3 signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 4719–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, E.-M.; Park, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, H.-R.; Song, H.-K.; Hong, O.-Y.; So, H.-S.; Yang, S.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; et al. Fisetin regulates TPA-induced breast cell invasion by suppressing matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation via the PKC/ROS/MAPK pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 764, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Chen, M.; Tseng, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Viswanadha, V.P.; Wang, G.; Huang, C. Fisetin activates Hippo pathway and JNK/ERK/AP-1 signaling to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of human osteosarcoma cells via ZAK overexpression. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, Y.; Afaq, F.; Johnson, J.J.; Mukhtar, H. A plant flavonoid fisetin induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells by inhibition of COX2 and Wnt/EGFR/NF-κB-signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-H.; Lee, S.; Son, H.-Y.; Park, S.-B.; Kim, M.-S.; Choi, E.-J.; Singh, T.S.K.; Ha, J.-H.; Lee, M.-G.; Kim, J.-E.; et al. Flavonoids inhibit histamine release and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in mast cells. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2008, 31, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tu, Y.-C.; Lian, T.-W.; Hung, J.-T.; Yen, J.-H.; Wu, M.-J. Distinctive Antioxidant and Antiinflammatory Effects of Flavonols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9798–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, K.; Pittenger, M. Mesenchymal stem cells: Progress toward promise. Cytotherapy 2005, 7, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage Potential of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiał-Wysocka, A.; Kot, M.; Majka, M. The Pros and Cons of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapies. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongso, A.; Fong, C.-Y. The Therapeutic Potential, Challenges and Future Clinical Directions of Stem Cells from the Wharton’s Jelly of the Human Umbilical Cord. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2013, 9, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaraman, M.; John, A.; Koshy, S.; Ranjan, R.; Anudeep, T.C.; Jain, R.; Swati, K.; Jha, N.K.; Sharma, A.; Kesari, K.K.; et al. Fostering mesenchymal stem cell therapy to halt cytokine storm in COVID-19. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, K.; Sun, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, M.; Gao, C.; Fu, L.; Li, H.; Sui, X.; Guo, Q.; Liu, S. Recent Developed Strategies for Enhancing Chondrogenic Differentiation of MSC: Impact on MSC-Based Therapy for Cartilage Regeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Aziza, F.A.; Zaki, A.K.A.; El-Maaty, A.A. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell (BM-MSC): A tool of cell therapy in hydatid experimentally infected rats. Cell Regen. 2019, 8, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucerova, L.; Skolekova, S.; Demkova, L.; Bohovic, R.; Matuskova, M. Long-term efficiency of mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated CD-MSC/5FC therapy in human melanoma xenograft model. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augello, A.; De Bari, C. The Regulation of Differentiation in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, H.; Mir, L.M.; Andre, F.M. In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells generates cell layers with distinct properties. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Steinberg, D.R.; Burdick, J.A.; Mauck, R.L. Extracellular vesicles mediate improved functional outcomes in engineered cartilage produced from MSC/chondrocyte cocultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.; Cabral, A.T.; Fernandes, M. Human bone cell cultures in biocompatibility testing. Part I: Osteoblastic differen-tiation of serially passaged human bone marrow cells cultured in α-MEM and in DMEM. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, V.G.B.; Chaves-Neto, A.H.; de Barros, T.L.; Oliveira, S. Soluble yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) extract enhances in vitro osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 244, 112131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jin, D.; Wu, J.-Q.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Fu, S.; Mei, G.; Zou, Z.-L.; Ma, S.-H. Neuropeptide Y stimulates osteoblastic differentiation and VEGF expression of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells related to canonical Wnt signaling activating in vitro. Neuropeptides 2016, 56, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K.-C.; Kim, J.Y.; Chang, W.; Kim, D.-S.; Lim, S.; Kang, S.-M.; Song, B.-W.; Ha, H.-Y.; Huh, Y.J.; Choi, I.-G.; et al. Chemicals that modulate stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7467–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, G.; Dupont, S.; Piccolo, S. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shou, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Zheng, C.; Han, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Zang, X.; Shao, C.; et al. An osteopontin-integrin interaction plays a critical role in directing adipogenesis and osteogenesis by mesen-chymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler, A.J.; Sen, S.; Sweeney, H.L.; Discher, D.E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 2006, 126, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Yin, F.; Wang, N.; Ma, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, L.; Zong, Y.; Shan, H.; Xia, W.; Lin, Y.; et al. Involvement of mechanosensitive ion channels in the effects of mechanical stretch induces osteogenic differen-tiation in mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Ju, Y.; Shen, X.; Luo, Q.; Shi, Y.; Qin, J. Mechanical stretch promotes proliferation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2007, 58, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, Q.; Ge, L.; Zhou, Q.; Warszawik, E.M.; Bron, R.; Lai, K.W.C.; Van Rijn, P. Topography induced stiffness alteration of stem cells influences osteogenic differentiation. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormos, K.V.; Anso, E.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Eisenbart, J.; Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial Complex III ROS Regulate Adipocyte Differentiation. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X. Wild-type Smad3 gene enhances the osteoblastic differentiation of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 2005, 25, 674–678. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhu, T.; Shen, Y.; Tang, X.; Fang, L.; Xu, Y. Cross-Talking Between PPAR and WNT Signaling and its Regulation in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 11, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Sonoyama, W.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, C.; Krebsbach, P.H.; Giannobile, W.; Shi, S.; Wang, C.-Y. Noncanonical Wnt-4 Signaling Enhances Bone Regeneration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Craniofacial Defects through Activation of p38 MAPK. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 30938–30948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, B.C.; Zhang, X.; Aubel, D.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Fussenegger, M.; Deng, X. Role of YAP/TAZ in Cell Lineage Fate Determination and Related Signaling Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorthongpanich, C.; Thumanu, K.; Tangkiettrakul, K.; Jiamvoraphong, N.; Laowtammathron, C.; Damkham, N.; U-Pratya, Y.; Issaragrisil, S. YAP as a key regulator of adipo-osteogenic differentiation in human MSCs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.S.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, H.O. The Flavonoid Glabridin Induces OCT4 to Enhance Osteogenetic Potential in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.G.; Cong, Y.; Bao, N.R.; Li, Y.G.; Zhao, J.N. Quercetin stimulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell differentiation through an estrogen recep-tor-mediated pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.J.; Tsai, K.S.; Lin, L.C.; Lee, Y.T.; Chi, C.W.; Chang, M.C.; Tsai, T.H.; Hung, S.C. Catechin stimulates osteogenesis by enhancing PP2A activity in human mesenchymal stem cells. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, W.; Taira, M.; Chosa, N.; Kihara, H.; Ishisaki, A.; Kondo, H. Effects of apatite particle size in two apatite/collagen composites on the osteogenic differentiation profile of osteoblastic cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postiglione, L.; Di Domenico, G.; Ramaglia, L.; Montagnani, S.; Salzano, S.; Di Meglio, F.; Sbordone, L.; Vitale, M.; Rossi, G. Behavior of SaOS-2 Cells Cultured on Different Titanium Surfaces. J. Dent. Res. 2003, 82, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manochantr, S.; Marupanthorn, K.; Tantrawatpan, C.; Kheolamai, P. The expression of neurogenic markers after neuronal induction of chorion-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Neurol. Res. 2014, 37, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri-Pellizzeri, L.; De Melo, N.; Ahmed, I.; Grant, D.M.; Scammell, B.; Sottile, V. Live Quantitative Monitoring of Mineral Deposition in Stem Cells Using Tetracycline Hydrochloride. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2018, 24, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchtler, H.; Meloan, S.N.; Terry, M.S. On the History and Mechanism of Alizarin and Alizarin Red S Stains for Calcium. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1969, 17, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.A.; Gunn, W.G.; Peister, A.; Prockop, D.J. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: Comparison with cetylpyri-dinium chloride extraction. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 329, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkman, J.E.N.; Cathcart, J.A.; Xu, F.; Bartolini, M.E.; Amon, J.E.; Stevens, K.M.; Colarusso, P. An introduction to the wound healing assay using live-cell microscopy. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2014, 8, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearngam, P.; Kumkate, S.; Okada, S.; Janvilisri, T. Andrographolide Inhibits Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Migration by Down-Regulation of Claudin-1 via the p-38 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, M.B.; Ronkina, N.; Schwermann, J.; Kotlyarov, A.; Gaestel, M. Fluorescence-based quantitative scratch wound healing assay demonstrating the role of MAPKAPK-2/3 in fibroblast migration. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2009, 66, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justus, C.R.; Leffler, N.; Ruiz-Echevarria, M.; Yang, L.V. In vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assays. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, e51046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, P.; Chen, F.; Dong, Z.; Yang, H.; Guan, K.-L.; Xu, Y. Structural insights into the YAP and TEAD complex. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. Compound Summary for CID 5281614. 2020. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Fisetin (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Gordon, J.C.; Myers, J.B.; Folta, T.; Shoja, V.; Heath, L.S.; Onufriev, A. H++: A server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W368–W371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford CT, 2, Gaussian 09, Revision D. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=17777290897844538463&hl=en&oi=scholarr (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Schepers, B.; Gohlke, H. AMBER-DYES in AMBER: Implementation of fluorophore and linker parameters into AmberTools. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 221103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, D.M.; Darden, T.A.; Pedersen, L.G. The effect of long-range electrostatic interactions in simulations of macromolecular crystals: A comparison of the Ewald and truncated list methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 8345–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Brooks, B.R. Reformulation of the self-guided molecular simulation method. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 094112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.R.; McGee, T.D.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA.py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Morad, V.; Cohen-Sfady, M.; Rousso-Noori, L.; Zanin-Zhorov, A.; Cohen, S.; Cohen, I.R.; Zipori, D. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood 2006, 109, 1422–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Liang, Z.; Wu, P.; Li, R.; You, B.; Yang, L.; et al. YAP signaling in gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells is critical for its promoting role in cancer pro-gression. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Geng, J.; Chen, L. Role of Hippo signaling in regulating immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Sun, B.; Fu, J.; Li, T.Z. Fisetin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury via TLR4-Mediated NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway in Rats. Inflammation 2016, 39, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léotoing, L.; Davicco, M.-J.; Lebecque, P.; Wittrant, Y.; Coxam, V. The flavonoid fisetin promotes osteoblasts differentiation through Runx2 transcriptional activity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, W.N.; Ali, A.M.; Subramani, T.; Alitheen, N.B.M.; Hamid, M.; Samsudin, A.R.; Yeap, S.K. Rapid growth and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from human bone marrow. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 9, 2202–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- McNamara, L.; Majeska, R.; Weinbaum, S.; Friedrich, V.; Schaffler, M. Attachment of Osteocyte Cell Processes to the Bone Matrix. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2009, 292, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.A.; Sessions, R.B.; Shoemark, D.K.; Williams, C.; Ebrahimighaei, R.; McNeill, M.C.; Crump, M.P.; McKay, T.R.; Harris, G.; Newby, A.C.; et al. Antiproliferative and Antimigratory Effects of a Novel YAP–TEAD Interaction Inhibitor Identified Using in Silico Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, J.K.; Crawford, J.J.; Noland, C.L.; Schmidt, S.; Zbieg, J.R.; Lacap, J.A.; Zang, R.; Miller, G.M.; Zhang, Y.; Beroza, P.; et al. Small Molecule Dysregulation of TEAD Lipidation Induces a Dominant-Negative Inhibition of Hippo Pathway Signaling. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorthongpanich, C.; Charoenwongpaiboon, T.; Supakun, P.; Klaewkla, M.; Kheolamai, P.; Issaragrisil, S. Fisetin Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via the Inhibition of YAP. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060879

Lorthongpanich C, Charoenwongpaiboon T, Supakun P, Klaewkla M, Kheolamai P, Issaragrisil S. Fisetin Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via the Inhibition of YAP. Antioxidants. 2021; 10(6):879. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060879

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorthongpanich, Chanchao, Thanapon Charoenwongpaiboon, Prapasri Supakun, Methus Klaewkla, Pakpoom Kheolamai, and Surapol Issaragrisil. 2021. "Fisetin Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via the Inhibition of YAP" Antioxidants 10, no. 6: 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060879

APA StyleLorthongpanich, C., Charoenwongpaiboon, T., Supakun, P., Klaewkla, M., Kheolamai, P., & Issaragrisil, S. (2021). Fisetin Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via the Inhibition of YAP. Antioxidants, 10(6), 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10060879