Astaxanthin-, β-Carotene-, and Resveratrol-Rich Foods Support Resistance Training-Induced Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experiment Design

2.3. Resistance Exercise Training

2.4. Indirect Metabolic Performance

2.5. Serum Carbonylated Protein

2.6. Subjective Fatigue

2.7. Nutrient Intake

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Body Composition

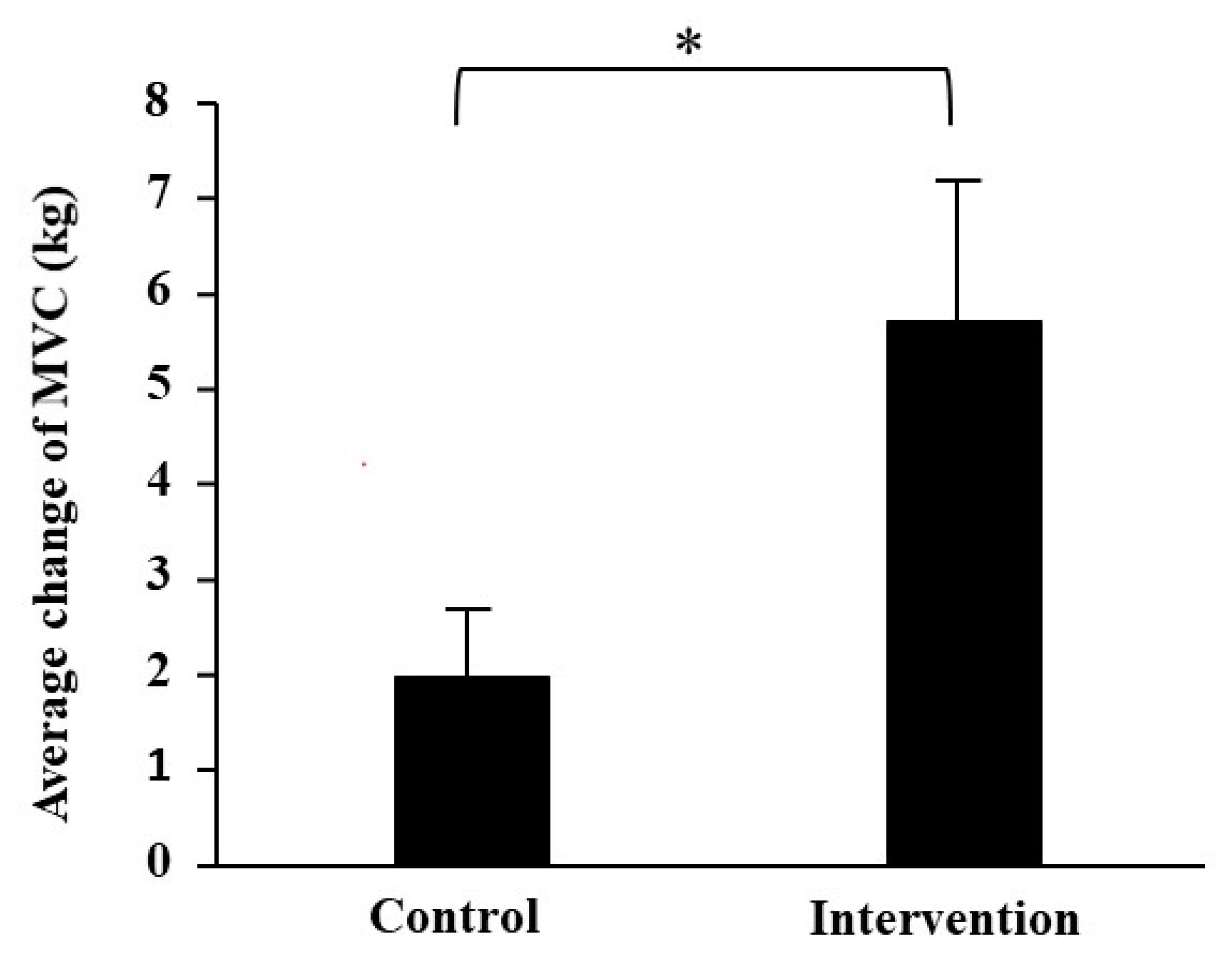

3.2. Muscle Strength

3.3. Metabolic Performance

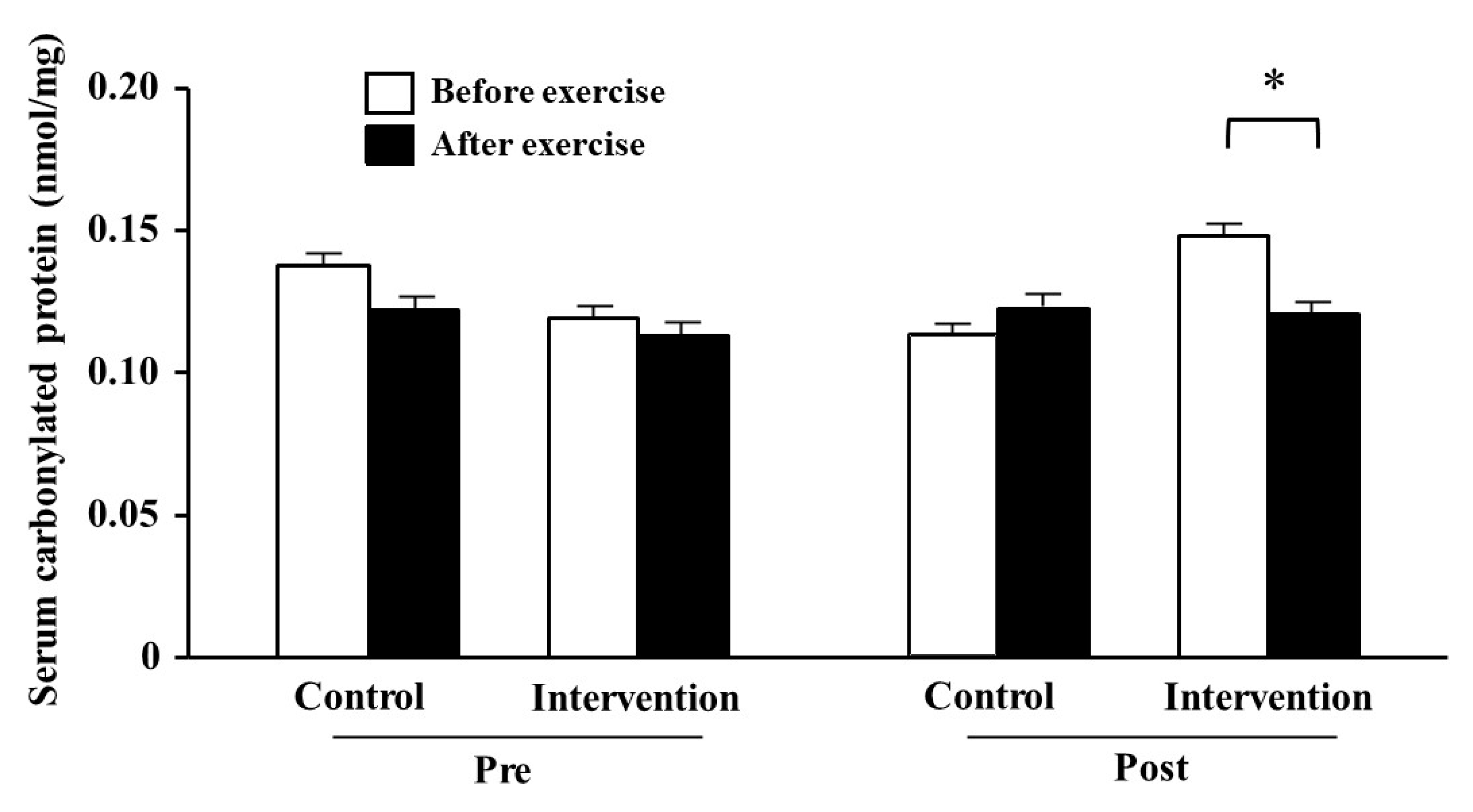

3.4. Serum Carbonylated Protein

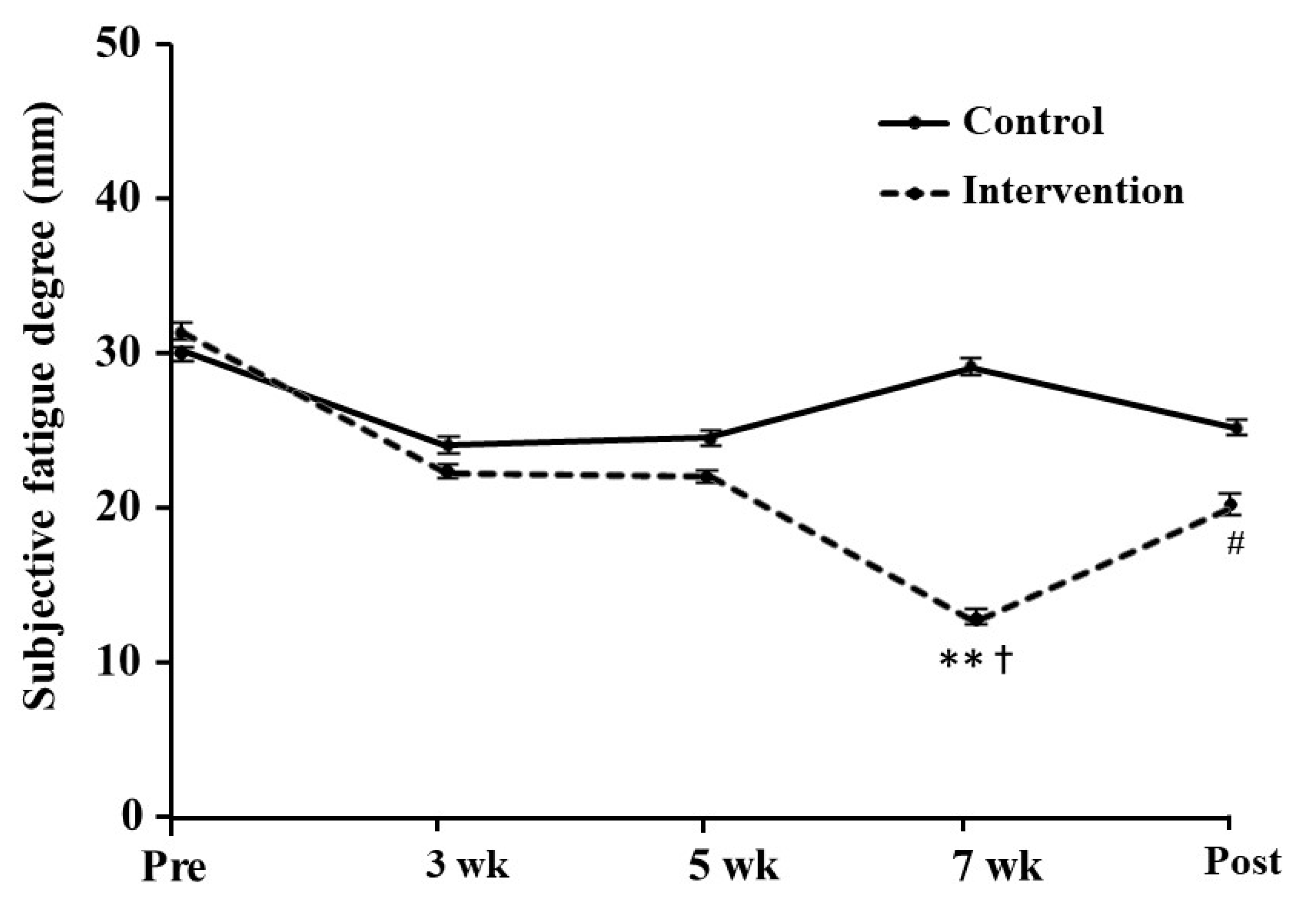

3.5. Subjective Fatigue

3.6. Nutrients Intake

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallagher, D.; Belmonte, D.; Deurenberg, P.; Wang, Z.; Krasnow, N.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Heymsfield, S.B. Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1998, 275, E249–E258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, J.J. Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: A synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Burd, N.A.; Phillips, S.M. Nutritional regulation of muscle protein synthesis with resistance exercise: Strategies to enhance anabolism. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patti, M.-E.; Brambilla, E.; Luzi, L.; Landaker, E.J.; Kahn, C.R. Bidirectional modulation of insulin action by amino acids. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, J.L.; Goforth, H.W., Jr.; Damon, B.M.; McCauley, T.R.; Parsons, E.C.; Price, T.B. Early postexercise muscle glycogen recovery is enhanced with a carbohydrate-protein supplement. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, L.; Malmstena, Å.L. Dietary Supplementation with Astaxanthin-Rich Algal Meal. Carotenoid Sci. 2008, 13, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kitakaze, T.; Harada, N.; Imagita, H.; Yamaji, R. β-Carotene Increases Muscle Mass and Hypertrophy in the Soleus Muscle in Mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2015, 61, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.T.; Yin, Y.; Yang, Y.J.; Lv, P.J.; Shi, Y.; Lu, L.; Wei, L.B. Resveratrol prevents TNF-α-induced muscle atrophy via regulation of Akt/mTOR/FoxO1 signaling in C2C12 myotubes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 19, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, A.; Luzi, L.; Senesi, P.; Mazzocchi, N.; Terruzzi, I. Resveratrol promotes myogenesis and hypertrophy in murine myoblasts. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A.; Aoi, W.; Abe, R.; Kobayashi, Y.; Wada, S.; Kuwahata, M.; Higashi, A. Combined intake of astaxanthin, beta-carotene, and resveratrol elevates protein synthesis during muscle hypertrophy in mice. Nutrition 2020, 69, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achten, J.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Maximal fat oxidation during exercise in trained men. Int. J. Sports Med. 2003, 24, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Nitzke, S. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Total diet approach to healthy eating. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2013, 113, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritis, I.; Rousseau, A.S. Does physical exercise modify antioxidant requirements? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2008, 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narici, M.V.; Hoppeler, H.; Kayser, B.; Landoni, L.; Claassen, H.; Gavardi, C.; Conti, M.; Cerretelli, P. Human quadriceps cross-sectional area, torque and neural activation during 6 months strength training. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1996, 157, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Atkinson, S.A.; MacDougall, J.D.; Chesley, A.; Phillips, S.; Schwarcz, H.P. Evaluation of protein requirements for trained strength athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 73, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.; Townsend, J.R.; Vantrease, W.C.; Marshall, A.C.; Henry, R.N.; Heffington, S.H.; Johnson, K.D. Acute beetroot juice administration improves peak isometric force production in adolescent males. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.D.; Looney, D.P.; Miller, M.J.; DuPont, W.H.; Pryor, L.; Creighton, B.C.; Sterczala, A.J.; Szivak, T.K.; Hooper, D.R.; Maresh, C.M. The effects of nitrate-rich supplementation on neuromuscular efficiency during heavy resistance exercise. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, T.D.; Saunders, D.H. Effect of caffeine ingestion on maximal voluntary contraction strength in upper-and lower-body muscle groups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 3239–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnio, S.; LoVerso, F.; Baraibar, M.A.; Longa, E.; Khan, M.M.; Maffei, M.; Reischl, M.; Canepari, M.; Loefler, S.; Kern, H. Autophagy impairment in muscle induces neuromuscular junction degeneration and precocious aging. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.P.; Shanes, A. Calcium influx in skeletal muscle at rest, during activity, and during potassium contracture. J. Gen. Physiol. 1959, 42, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moopanar, T.R.; Allen, D.G. Reactive oxygen species reduce myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in fatiguing mouse skeletal muscle at 37 °C. J. Physiol. 2005, 564, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Yamashita, E.; Miki, W. Quenching activities of common hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants against singlet oxygen using chemiluminescence detection system. Soc. Carot. Res. 2007, 11, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, H.; Misra, B.R. EPR studies on the superoxide-scavenging capacity of the nutraceutical resveratrol. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2008, 313, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polley, K.R.; Jenkins, N.; O’Connor, P.; McCully, K. Influence of exercise training with resveratrol supplementation on skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.H.; Aoi, W.; Takami, M.; Terajima, H.; Tanimura, Y.; Naito, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Yoshikawa, T. The astaxanthin-induced improvement in lipid metabolism during exercise is mediated by a PGC-1α increase in skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2014, 54, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Dohl, J.; Chen, Y.; Gasier, H.G.; Deuster, P. Astaxanthin but not quercetin preserves mitochondrial integrity and function, ameliorates oxidative stress, and reduces heat-induced skeletal muscle injury. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 13292–13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Liu, C.-C.; Tsao, J.-P.; Hsu, C.-L.; Cheng, I.-S. Effects of Oral Resveratrol Supplementation on Glycogen Replenishment and Mitochondria Biogenesis in Exercised Human Skeletal Muscle. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Hills, A.P.; Pal, S. The effect of 12 weeks of aerobic, resistance or combination exercise training on cardiovascular risk factors in the overweight and obese in a randomized trial. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, M.; Aoi, W.; Terajima, H.; Tanimura, Y.; Wada, S.; Higashi, A. Effect of dietary antioxidant-rich foods combined with aerobic training on energy metabolism in healthy young men. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 64, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vina, J.; Gimeno, A.; Sastre, J.; Desco, C.; Asensi, M.; Pallardo, F.V.; Cuesta, A.; Ferrero, J.A.; Terada, L.S.; Repine, J.E. Mechanism of free radical production in exhaustive exercise in humans and rats; role of xanthine oxidase and protection by allopurinol. IUBMB Life 2000, 49, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, D.L.; Silva, L.A.; Tromm, C.B.; da Rosa, G.L.; Silveira, P.C.; de Souza, C.T.; Latini, A.; Pinho, R.A. Impact of different resistance training protocols on muscular oxidative stress parameters. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, J.A.; Burke, L.M.; Phillips, S.M.; Spriet, L.L. Nutritional modulation of training-induced skeletal muscle adaptations. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 110, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Klöting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Blüher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8665–8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Domenech, E.; Romagnoli, M.; Arduini, A.; Borras, C.; Pallardo, F.V.; Sastre, J.; Vina, J. Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, G.; Hamarsland, H.; Cumming, K.; Johansen, R.; Hulmi, J.; Børsheim, E.; Wiig, H.; Garthe, I.; Raastad, T. Vitamin C and E supplementation alters protein signalling after a strength training session, but not muscle growth during 10 weeks of training. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 5391–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.A.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Paschalis, V.; Koutsias, S.; Panayiotou, G.; Fatouros, I.G.; Koutedakis, Y.; Jamurtas, A.Z. No effect of antioxidant supplementation on muscle performance and blood redox status adaptations to eccentric training. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.D.; Napolitano, G.; Venditti, P. Mediators of physical activity protection against ROS-linked skeletal muscle damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoi, W.; Naito, Y.; Takanami, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Sakuma, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Yoshida, N.; Yoshikawa, T. Oxidative stress and delayed-onset muscle damage after exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; McHugh, M.; Padilla-Zakour, O. Efficacy of a tart cherry juice blend in preventing the symptoms of muscle damage. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arent, S.M.; Senso, M.; Golem, D.L.; McKeever, K.H. The effects of theaflavin-enriched black tea extract on muscle soreness, oxidative stress, inflammation, and endocrine responses to acute anaerobic interval training: A randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2010, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolny, G.; Aucello, M.; Rizzuto, E.; Beccafico, S.; Mammucari, C.; Bonconpagni, S.; Belia, S.; Wannenes, F.; Nicoletti, C.; Del Prete, Z. Skeletal muscle is a primary target of SOD1G93A-mediated toxicity. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.C.; Lustgarten, M.S.; Liu, Y.; Muller, F.L.; Bhattacharya, A.; Liang, H.; Salmon, A.B.; Brooks, S.V.; Larkin, L.; Hayworth, C.R. Increased superoxide in vivo accelerates age-associated muscle atrophy through mitochondrial dysfunction and neuromuscular junction degeneration. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, S.; Kogure, K.; Abe, K.; Kimata, Y.; Kitahama, K.; Yamashita, E.; Terada, H. Efficient radical trapping at the surface and inside the phospholipid membrane is responsible for highly potent antiperoxidative activity of the carotenoid astaxanthin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1512, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucciolla, V.; Borriello, A.; Oliva, A.; Galletti, P.; Zappia, V.; Della Ragione, F. Resveratrol: From basic science to the clinic. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 2495–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E.; Saito, T.; Kawakami, A.; Kamiya, Y. Inhibition of oxidation of methyl linoleate in solution by vitamin E and vitamin C. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 4177–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Onodera, A.; Saito, E.; Tanabe, M.; Yajima, K.; Takahashi, J.; Nguyen, V.C. Effect of astaxanthin in combination with alpha-tocopherol or ascorbic acid against oxidative damage in diabetic ODS rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2008, 54, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical Characteristics | Control | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | Pre | Post | Change | |

| Body weight (kg) | 59.7 ± 1.9 | 60.0 ± 1.9 | 0.10 ± 0.60 | 59.1 ± 1.6 | 59.7 ± 1.5 | 0.56 ± 0.62 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.4 ± 0.5 | 20.6 ± 0.5 | 0.24 ± 0.23 | 20.3 ± 0.5 | 20.4 ± 0.5 | 0.10 ± 0.10 |

| Body fat (%) | 14.3 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.3 | −0.44 ± 0.37 | 14.8 ± 1.2 | 14.6 ± 0.9 | −0.18 ± 0.45 |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 28.4 ± 0.8 | 28.8 ± 0.8 * | 0.48 ± 0.14 | 28.3 ± 0.7 | 28.6 ± 0.7 * | 0.31 ± 0.13 |

| MVC of right leg (kg) | 25.3 ± 1.9 | 26.8 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 2.6 | 32.4 ± 2.5 ** | 6.4 ± 2.2 |

| MVC of left leg (kg) | 23.2 ± 2.3 | 25.6 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 24.7 ± 2.2 | 30.0 ± 2.2 ** | 5.0 ± 1.2 |

| Metabolic Parameters | Control | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | Pre | Post | Change | |

| Oxygen consumption (mL/kg/min) | 3.42 ± 0.11 | 3.44 ± 0.08 | 0.02 ± 0.11 | 3.35 ± 0.10 | 3.57 ± 0.10 * | 0.18 ± 0.10 |

| Respiratory quotient | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 * | −0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | −0.02 ± 0.02 |

| Carbohydrate utilization (mg/gB.W./min) | 2.53 ± 0.19 | 2.05 ± 0.21 * | −0.49 ± 0.19 | 2.67 ± 0.16 | 2.57 ± 0.30 | −0.10 ± 0.30 |

| Fat utilization (mg/gB.W./min) | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.08 * | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.07 |

| Energy and Nutrients | Control | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 10 Weeks | Pre | 10 Weeks | |

| Energy (kcal/d) | 2144 ± 92 | 2352 ± 112 | 2150 ± 91 | 2371 ± 105 |

| Protein (g/d) | 80.0 ± 5.2 | 93.6 ± 4.2 * | 95.5 ± 5.2 | 107.8 ± 6.1 |

| Fat (g/d) | 70.4 ± 5.7 | 77.0 ± 7.3 | 71.8 ± 5.4 | 74.2 ± 5.8 |

| Carbohydrate (g/d) | 283.0 ± 16.7 | 306.0 ± 20.0 | 302.8 ± 15.7 | 310.7 ± 18.2 |

| Vitamin A (µg/d) | 423 ± 31 | 416 ± 56 | 833 ± 309 | 824 ± 272 |

| Vitamin C (mg/d) | 51 ± 5 | 70 ± 9 | 63 ± 3 | 91 ± 11 |

| Vitamin E (mg/d) | 7 ± 0.6 | 8 ± 0.6 | 7 ± 0.5 | 11 ± 0.7 † |

| Astaxanthin (mg/d) | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.3 ± 0.12 | 1.87 ± 0.48 ** † |

| β-carotene (µg/d) | 2141 ± 235 | 2048 ± 209 | 2126 ± 175.5 | 12,130 ± 609.6 ** † |

| Resveratrol (µg/d) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 ** † |

| Salt (g/d) | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 0.6 | 10.0 ± 0.6 | 9.5 ± 0.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawamura, A.; Aoi, W.; Abe, R.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kuwahata, M.; Higashi, A. Astaxanthin-, β-Carotene-, and Resveratrol-Rich Foods Support Resistance Training-Induced Adaptation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10010113

Kawamura A, Aoi W, Abe R, Kobayashi Y, Kuwahata M, Higashi A. Astaxanthin-, β-Carotene-, and Resveratrol-Rich Foods Support Resistance Training-Induced Adaptation. Antioxidants. 2021; 10(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawamura, Aki, Wataru Aoi, Ryo Abe, Yukiko Kobayashi, Masashi Kuwahata, and Akane Higashi. 2021. "Astaxanthin-, β-Carotene-, and Resveratrol-Rich Foods Support Resistance Training-Induced Adaptation" Antioxidants 10, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10010113

APA StyleKawamura, A., Aoi, W., Abe, R., Kobayashi, Y., Kuwahata, M., & Higashi, A. (2021). Astaxanthin-, β-Carotene-, and Resveratrol-Rich Foods Support Resistance Training-Induced Adaptation. Antioxidants, 10(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10010113