A Prefrontal Neuromodulation Route for Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Perspective Supported by Recovery During Left-DLPFC rTMS

Abstract

1. Perspective and Rationale

1.1. Evidence Snapshot: Established and Emerging Interventions for Acquired Olfactory Dysfunction

1.2. Neuropsychological and Functional Consequences: Targets for Assessment and Integrated Care

2. Clinical Vignette and Supporting Evidence

2.1. Patient and Baseline Assessment

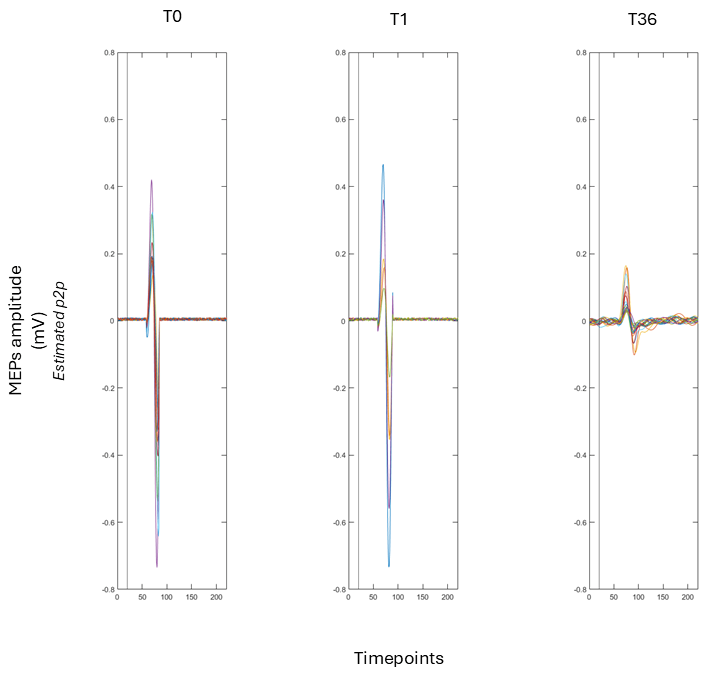

2.2. Neuromodulation Protocol and Monitoring

2.2.1. Cortical Excitability Assessment

2.2.2. rTMS Protocol

2.3. Outcomes

3. Mechanistic Interpretation and Clinical Implications

4. Research Agenda and Future Directions

- Use standardized psychophysical olfactory testing (e.g., threshold, discrimination, identification) at baseline and follow-up, complemented by ecologically valid diaries for within-person trajectories.

- Adopt randomized, sham-controlled designs (or at minimum multiple-baseline single-case designs) and report expectancy and blinding integrity.

- Specify and justify targeting (neuronavigation when possible) and systematically explore dose parameters (frequency, intensity, total pulses, number of sessions) and laterality.

- Evaluate combinations with evidence-informed olfactory training and/or hedonic stimulation to leverage attention and reward mechanisms in multisensory recovery.

- Add mechanistic biomarkers (EEG, fMRI, PET, connectivity measures, or TMS-EMG indices) to test network-level hypotheses and identify responders.

- Report safety and tolerability in older adults and in patients with head trauma, including adverse event monitoring and follow-up durability of gains.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE-R | Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory–II |

| CE | cortical excitability |

| CRIq | Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire |

| CT | computed tomography |

| DLPFC | dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level |

| EMG | electromyography |

| FAS | Fatigue Assessment Scale |

| FDI | first dorsal interosseous |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| MEP | motor-evoked potential |

| M1 | primary motor cortex |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| OD | olfactory dysfunction |

| OFC | orbitofrontal cortex |

| OT | olfactory training |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| PTOD | post-traumatic olfactory dysfunction |

| QOD | Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders |

| QOD-NS | negative statements subscale of the Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders |

| QOD-P | parosmia subscale of the Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders |

| rMT | resting motor threshold |

| rTMS | repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| Self-MOQ | Self-reported Mini Olfactory Questionnaire |

| spTMS | single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| T0 | baseline |

| T36 | post-treatment |

References

- De Luca, R.; Bonanno, M.; Rifici, C.; Quartarone, A.; Calabró, R. Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Scoping Review of Assessment and Rehabilitation Approaches. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1193406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.; Costanzo, R.; Reiter, E. Head Trauma and Olfactory Function. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 4, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, I. Managing Post-Traumatic Olfactory Disorders. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 2022, 10, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limphaibool, N.; Iwanowski, P.; Kozubski, W.; Świdziński, T.; Frankowska, A.; Kaminska, I.; Linkowska-Świdzińska, K.; Sekula, A.; Świdziński, P.; Maciejewska-Szaniec, Z.; et al. Subjective and Objective Assessments of Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskynitopoulos, P.J.; Stippler, M.; Kasper, E.M. Post-Traumatic Anosmia in Patients with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI): A Systematic and Illustrated Review. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2016, 7, S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K.; Leland, E.; Seal, S.; Schneider, A.; Rowan, N.; Kamath, V. Olfactory Dysfunction Following Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2022, 33, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Alapati, R.; Wagoner, S.; Nieves, A.B.; Bird, C.; Wright, R.; Jafri, S.; Rippee, M.; Villwock, J. Evaluating Olfactory Function and Quality of Life in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2024, 14, 1391–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Farruggia, M.; Small, D.; Veldhuizen, M. Post-Traumatic Olfactory Loss and Brain Response beyond Olfactory Cortex. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltagi, A.K.; Saltagi, M.Z.; Nag, A.; Wu, A.W.; Higgins, T.F.; Knisely, A.M.; Ting, J.; Illing, E. Diagnosis of Anosmia and Hyposmia: A Systematic Review. Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 12, 21526567211026568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullakçi, H.; Sonkaya, A.R. The Investigation of the Effects of Repetitive Transcranialmagnetic Stimulation Treatment on Taste and Smell Sensations in Depressed Patients. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars. 2021, 58, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzio, M.; D’Agata, F.; Palermo, S.; Rubino, E.; Zucca, M.; Galati, A.; Pinessi, L.; Castellano, G.; Rainero, I. Neural Correlates of Reduced Awareness in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Frontotemporal Dementia. Exp. Gerontol. 2016, 83, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzio, M.; Palermo, S.; Skyt, I.; Vase, L. Lessons Learned From Nocebo Effects in Clinical Trials for Pain Conditions and Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzio, M.; Palermo, S. Nocebo Effects and Psychotropic Drug Action—An Update. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.; Stohler, C.; Herr, D. Role of the Prefrontal Cortex in Pain Processing. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 56, 1137–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, S. Frailty, Vulnerability, and Plasticity: Towards a New Medicine of Complexity. In Frailty in the Elderly—Understanding and Managing Complexity; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Amanzio, M.; Palermo, S. Editorial: Physical and Cognitive Frailty in the Elderly: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 698819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparelli, E.; Schleyer, B.; Zhai, T.; Gu, H.; Abulseoud, O.; Yang, Y. High-Frequency Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Combined With Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Reveals Distinct Activation Patterns Associated With Different Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Stimulation Sites. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ponzio, M.; Makris, N.; Tenerini, C.; Grassi, E.; Ragone, S.; Pallanti, S. RTMS Investigation of Resistant Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders: Efficacy of Targeting the Reward System. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1035469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Guo, R.; Tan, B.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.; Ye, Y.; Che, X. Prefrontal Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Changes Cortical Excitability across Local and Distributed Brain Regions. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025, 173, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Luan, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z. The Effect of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex on the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients With Cognitive Impairment: A Double-Blinded, Randomized, and Sham Control Trial. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Fan, L.; Zhu, W.; Xiu, Y.; Liu, Y. Differential Effects of High-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation over the Left and Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 46, 3157–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, R.; Padberg, F.; Giron, C.; Lin, T.; Zhang, B.; Brunoni, A.; Kranz, G. Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex on Symptom Domains in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Cross-Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Allen, R.; Juma, A.; Chowdhury, R.; Burke, M. Does Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Improve Cognitive Function in Age-related Neurodegenerative Diseases? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Nazzi, C.; Fullana, M.A.; di Pellegrino, G.; Borgomaneri, S. “Nip It in the Bud”: Low-Frequency RTMS of the Prefrontal Cortex Disrupts Threat Memory Consolidation in Humans. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 178, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Nazzi, C.; Di Fazio, C.; Borgomaneri, S. The Role of Pre-Supplementary Motor Cortex in Action Control with Emotional Stimuli: A Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1536, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Serio, G.; Battaglia, S. Please, Don’t Do It! Fifteen Years of Progress of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation in Action Inhibition. Cortex 2020, 132, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Vitale, F.; Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A. Early Right Motor Cortex Response to Happy and Fearful Facial Expressions: A TMS Motor-Evoked Potential Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Garofalo, S.; Tortora, F.; Avenanti, A.; di Pellegrino, G. State-Dependent TMS over Prefrontal Cortex Disrupts Fear-Memory Reconsolidation and Prevents the Return of Fear. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 3672–3679.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbert, L.; Neige, C.; Dumas, M.; Bensafi, M.; Mandairon, N.; Brunelin, J. Combining Pleasant Olfactory and BRAin Stimulations in Treatment-Resistant Depression (COBRA): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1451096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzio, M.; Canessa, N.; Bartoli, M.; Cipriani, G.E.; Palermo, S.; Cappa, S.F. Lockdown Effects on Healthy Cognitive Aging During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 685180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Bunce, J.G.; Barbas, H. Prefrontal-Hippocampal Pathways Underlying Inhibitory Control over Memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 134, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Di Fazio, C.; Vicario, C.M.; Avenanti, A. Neuropharmacological Modulation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate, Noradrenaline and Endocannabinoid Receptors in Fear Extinction Learning: Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Di Fazio, C.; Mazzà, M.; Tamietto, M.; Avenanti, A. Targeting Human Glucocorticoid Receptors in Fear Learning: A Multiscale Integrated Approach to Study Functional Connectivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Cardellicchio, P.; Di Fazio, C.; Nazzi, C.; Fracasso, A.; Borgomaneri, S. The Influence of Vicarious Fear-Learning in ‘Infecting’ Reactive Action Inhibition. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 946263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Cardellicchio, P.; Di Fazio, C.; Nazzi, C.; Fracasso, A.; Borgomaneri, S. Stopping in (e)Motion: Reactive Action Inhibition When Facing Valence-Independent Emotional Stimuli. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 998714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, S.; Di Fazio, C.; Scaliti, E.; Stanziano, M.; Nigri, A.; Tamietto, M. Cortical Excitability and the Aging Brain: Toward a Biomarker of Cognitive Resilience. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1542880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, C.; Tamietto, M.; Stanziano, M.; Nigri, A.; Scaliti, E.; Palermo, S. Cortico–Cortical Paired Associative Stimulation (CcPAS) in Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Quali-Quantitative Approach to Potential Therapeutic Mechanisms and Applications. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, C.; Scaliti, E.; Stanziano, M.; Nigri, A.; Demichelis, G.; Tamietto, M.; Palermo, S. RTMS for Enhancing Cognitive Reserve: A Case Report. Brain Disord. 2025, 18, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, M.R.; Balderston, N.L.; Helmstetter, F.J. Prefrontal Cortical Regulation of Fear Learning. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, H.; Mende-Siedlecki, P.; Kross, E.F.; Weber, J.; Mischel, W.; Hart, C.L.; Ochsner, K.N. Prefrontal-Striatal Pathway Underlies Cognitive Regulation of Craving. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14811–14816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langdon, C.; Lehrer, E.; Berenguer, J.; Laxe, S.; Alobid, I.; Quintó, L.; Mariño-Sánchez, F.; Bernabeu, M.; Marin, C.; Mullol, J. Olfactory Training in Post-Traumatic Smell Impairment: Mild Improvement in Threshold Performances: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiai, N.I.M.; Mohamad, N.; Basri, H.; Mat, L.N.I.; Hoo, F.; Rashid, A.A.; Khan, A.H.K.Y.; Loh, W.; Baharin, J.; Fernandez, A.; et al. High-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation at Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Migraine Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Jerstad, T.; Andelic, N.; Røe, C.; Schanke, A. Olfactory Dysfunction, Gambling Task Performance and Intracranial Lesions after Traumatic Brain Injury. Neuropsychology 2010, 24, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhong, N.; Gan, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Ruan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; et al. High Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Methamphetamine Use Disorders: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 175, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Qi, M. Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Activation Can Accelerate Stress Recovery: A Repetitive Transcranial Stimulation Study. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giron, C.; Tang, A.; Jin, M.; Kranz, G. Antidepressant Efficacy of Administering Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (RTMS) with Psychological and Other Non-Pharmacological Methods: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2025, 55, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Ash, J.; Addison, A.; Philpott, C. Ask the Experts: An International Consensus on Managing Post-Infectious Olfactory Dysfunction Including COVID-19. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 2022, 10, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Vaira, L.A.; Saussez, S. Effectiveness of Olfactory Training in COVID-19 Patients with Olfactory Dysfunction: A Prospective Study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Hummel, T.; Menini, A. Adherence to Olfactory Training Improves Orthonasal and Retronasal Olfaction in Post-COVID-19 Olfactory Loss. Rhinology 2024, 62, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Y.; Pao, J.-B.; Lee, C.-H.; Lee, M.-C.; Wu, T.-T. Corticosteroids for COVID-19-Induced Olfactory Dysfunction: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.A.; Mohamady, A.A.; Elsayed, R.A.; Elawady, M.A.; Ghallab, A.F. Corticosteroid Nasal Spray for Recovery of Smell Sensation in COVID-19 Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaira, L.A.; Hopkins, C.; Petrocelli, M.; Lechien, J.R.; Cutrupi, S.; Salzano, G. Efficacy of Corticosteroid Therapy in the Treatment of Long-Lasting Olfactory Disorders in COVID-19 Patients. Rhinology 2021, 59, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Saussez, S.; Vaira, L.A.; De Riu, G.; Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Tirelli, G.; Michel, J.; Radulesco, T. Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma for COVID-19-Related Olfactory Dysfunction: A Controlled Study. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 170, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, A.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Hwang, S.H. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Persistent Olfactory Impairment After COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Rhinol. 2024, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stadio, A.; Gallina, S.; Cocuzza, S.; De Luca, P.; Ingrassia, A.; Oliva, S.; Sireci, F.; Camaioni, A.; Ferreli, F. Treatment of COVID-19 Olfactory Dysfunction with Olfactory Training, Palmitoylethanolamide with Luteolin, or Combined Therapy: A Blinded Controlled Multicenter Randomized Trial. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 4949–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestito, L.; Mori, L.; Trompetto, C. Impact of TDCS on Persistent COVID-19 Olfactory Dysfunction: A Double-Blind Sham-Controlled Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestito, L.; Ponzano, M.; Mori, L.; Trompetto, C.; Bandini, F. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (A-TDCS) and Olfactory Training in Persistent COVID-19 Anosmia. Brain Stimul. 2025, 18, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkin, R.I.; Levy, L.M.; Lin, C.S. Improvement in Smell and Taste Dysfunction after Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 32, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reden, J.; Lill, K.; Zahnert, T.; Haehner, A.; Hummel, T. Olfactory Function in Patients with Postinfectious and Posttraumatic Smell Disorders before and after Treatment with Vitamin A: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1906–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; Croy, I.; Hummel, T. Olfactory Loss and Quality of Life: A Review. Chem. Senses 2025, 50, bjaf023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Knill-Jones, R.; Van, J.; Sande, D. Observer Variability in Assessing Impaired Consciousness and Coma. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1978, 41, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment of Coma and Impaired Consciousness: A Practical Scale. Lancet 1974, 304, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, J.; Arnold, R.; Hodges, J.R. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): A Brief Cognitive Test Battery for Dementia Screening. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M.; Wolfson, D. Category Test and Trail Making Test as Measures of Frontal Lobe Functions. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1995, 9, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire (CRIq): A New Instrument for Measuring Cognitive Reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, J.; Michielsen, H.; Van Heck, G.L.; Drent, M. Measuring Fatigue in Sarcoidosis: The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS). Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.-S.; Kohlmann, T.; Janssen, M.F.; Buchholz, I. Psychometric Properties of the EQ-5D-5L: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 647–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolk, E.; Ludwig, K.; Rand, K.; van Hout, B.; Ramos-Goñi, J.M. Overview, Update, and Lessons Learned From the International EQ-5D-5L Valuation Work: Version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L Valuation Protocol. Value Health 2019, 22, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Vitale, F.; Gazzola, V.; Avenanti, A. Seeing Fearful Body Language Rapidly Freezes the Observer’s Motor Cortex. Cortex 2015, 65, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Vitale, F.; Avenanti, A. Early Motor Reactivity to Observed Human Body Postures Is Affected by Body Expression, Not Gender. Neuropsychologia 2020, 146, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Vitale, F.; Avenanti, A. Early Changes in Corticospinal Excitability When Seeing Fearful Body Expressions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracampo, R.; Tidoni, E.; Borgomaneri, S.; di Pellegrino, G.; Avenanti, A. Sensorimotor Network Crucial for Inferring Amusement from Smiles. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 5116–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Bo, Q.; Lei, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, M. High-Frequency RTMS over the Left DLPFC Improves the Response Inhibition Control of Young Healthy Participants: An ERP Combined (1)H-MRS Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1144757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabesan, P.; Lankappa, S.; Khalifa, N.; Krishnan, V.; Gandhi, R.; Palaniyappan, L. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Geriatric Depression: Promises and Pitfalls. World J. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lan, X.; Chen, C.; Ren, H.; Guo, Y. Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 723715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Nazzi, C.; Thayer, J.F. Heart’s Tale of Trauma: Fear-Conditioned Heart Rate Changes in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 148, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, F.; Chiappini, E.; Avenanti, A. Enhanced Action Performance Following TMS Manipulation of Associative Plasticity in Ventral Premotor-Motor Pathway. Neuroimage 2018, 183, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardi, A.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Fried, P.J.; Santarnecchi, E. The Role of Cognitive Reserve in Alzheimer’s Disease and Aging: A Multi-Modal Imaging Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1341–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Menardi, A.; Rossi, S.; Koch, G.; Hampel, H.; Vergallo, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Stern, Y.; Borroni, B.; Cappa, S.F.; Cotelli, M.; et al. Toward Noninvasive Brain Stimulation 2.0 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 75, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Ponzo, V.; Pellicciari, M.C.; Bonnì, S.; Picazio, S.; Mercuri, N.B.; Caltagirone, C.; Martorana, A.; Koch, G. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Predicts Cognitive Decline in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrini, S.; Fiori, F.; Chiappini, E.; Lucero, B.; Santarnecchi, E.; Avenanti, A. Cortico-Cortical Paired Associative Stimulation (CcPAS) over Premotor-Motor Areas Affects Local Circuitries in the Human Motor Cortex via Hebbian Plasticity. Neuroimage 2023, 271, 120027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, S.; Fiori, F.; Bevacqua, N.; Saracini, C.; Lucero, B.; Candidi, M.; Avenanti, A. Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity Induction Reveals Dissociable Supplementary- and Premotor-Motor Pathways to Automatic Imitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2404925121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrini, S.; Bevacqua, N.; Cataneo, A.; Chiappini, E.; Fiori, F.; Battaglia, S.; Romei, V.; Avenanti, A. Neurophysiological Markers of Premotor-Motor Network Plasticity Predict Motor Performance in Young and Older Adults. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustiniani, A.; Vallesi, A.; Oliveri, M.; Tarantino, V.; Ambrosini, E.; Bortoletto, M.; Masina, F.; Busan, P.; Siebner, H.R.; Fadiga, L.; et al. A Questionnaire to Collect Unintended Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Consensus Based Approach. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 141, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Pecorari, G.; Motatto, G.M.; Rivero, M.; Canale, A.; Albera, R.; Albera, A. Validation and Reliability of the Italian Version of the Self-Reported Mini Olfactory Questionnaire (Self-MOQ). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2024, 44, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardella, A.; Riva, G.; Preti, A.; Albera, A.; Luzi, L.; Albera, R.; Cadei, D.; Motatto, G.M.; Omenetti, F.; Pecorari, G.; et al. Italian Version of the Brief Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders (Brief-IT-QOD). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2023, 43, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedy, F.; Mazlan, M.; Danaee, M.; Bakar, M.Z.A. Post-Traumatic Brain Injury Olfactory Dysfunction: Factors Influencing Quality of Life. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2020, 277, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lei, Z.; Gilhooly, D.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Ritzel, R.; Li, H.; Wu, L.-J.; Liu, S.; Wu, J. Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Inflammatory Changes in the Olfactory Bulb Disrupt Neuronal Networks Leading to Olfactory Dysfunction. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 114, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.; Langdon, C.; Alobid, I.; Mullol, J. Olfactory Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury: The Role of Neurogenesis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Su, B.; Sun, Z.; Nie, B.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. Altered Glucose Metabolism of the Olfactory-Related Cortices in Anosmia Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 4813–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, M.; Chen, W.R. Neural Correlates of Olfactory Learning: Critical Role of Centrifugal Neuromodulation. Learn. Mem. 2010, 17, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Padmanabhan, K. Top-down Feedback Enables Flexible Coding Strategies in the Olfactory Cortex. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.S. Neuromodulation in the Olfactory Bulb. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, C.; Geisler, M.; Mayer, N.L.; Thierfelder, A.; Walter, M.; Hummel, T.; Croy, I. Modulating Salience Network Connectivity through Olfactory Nerve Stimulation. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E.; Del Bene, V.A.; Kamath, V.; Frank, J.S.; Billings, R.; Cho, D.-Y.; Byun, J.Y.; Jacob, A.; Anderson, J.N.; Visscher, K.; et al. Does Olfactory Training Improve Brain Function and Cognition? A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2023, 34, 155–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Fletcher, M.; Sullivan, R. Acetylcholine and Olfactory Perceptual Learning. Learn. Mem. 2004, 11, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ye, Z.Z.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X.; Huan, C. An Advance in Novel Intelligent Sensory Technologies: From an Implicit-tracking Perspective of Food Perception. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemann, U. Pharmaco-Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Studies of Motor Excitability. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 116, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gellrich, J.; Zickmüller, C.; Thieme, T.; Karpinski, C.; Fitze, G.; Smitka, M.; Von Der Hagen, M.; Schriever, V. Olfactory Function after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Children-a Longitudinal Case Control Study. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigrand, C.; Jobin, B.; Giguère, F.L.; Giguère, J.; Boller, B.; Frasnelli, J. Olfactory Perception in Patients with a Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Longitudinal Study. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, E.; Dinardo, L.; Costanzo, R. Effects of Head Injury on Olfaction and Taste. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 37, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention | Rationale/Mechanism | Typical Protocol (Examples) | Evidence Snapshot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory training (OT) (classic/modified/intensive) [47,48,49] | Peripheral + central plasticity; top-down attentional engagement; repeated odor exposure | 4 odors, 2×/day, ≥12 weeks; extended protocols (6–9 months); intensive variants in persistent post-COVID | Highest level of evidence across post-viral OD; recommended first-line. Benefits may increase when combined with adjuncts. |

| Corticosteroids (topical or systemic; selected cases) [50,51,52] | Anti-inflammatory effects; may help when sinonasal inflammation present or early post-viral phase | Short course systemic steroids or topical sprays; usually combined with OT | Evidence mixed/heterogeneous; commonly used but optimal indications unclear; risk–benefit individualized. |

| Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (intranasal/olfactory cleft injection) [53,54] | Pro-regenerative growth factors; anti-inflammatory; supports epithelial and neural repair | 1 mL per cleft, often repeated; protocols vary (injection vs. topical carriers) | Promising results in post-viral/post-COVID OD; growing evidence base, including meta-analyses; several trials ongoing. |

| Adjunct nutraceuticals (e.g., PEA-luteolin; omega-3, etc.) [55] | Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective pathways; modulation of glial activation (hypothesized) | Typically combined with OT; dosing varies by product and study | Preliminary evidence suggests OT + adjuncts may improve recovery vs. OT alone, but standardization and replication needed. |

| Neuromodulation: tDCS + OT [56,57] | Modulation of network excitability and plasticity; may enhance OT-driven learning | Anodal tDCS paired with OT (double-blind protocols reported) | RCT evidence emerging in persistent post-COVID anosmia; effect sizes and durability still being defined. |

| Neuromodulation: rTMS (prefrontal targets; case-based evidence) [58] | Top-down control of olfactory–limbic networks; dopaminergic/reward and attentional systems (hypothesized) | High-frequency rTMS over left DLPFC (protocols vary) | Sparse direct evidence for OD; case reports/case series suggest potential benefit; mechanistic rationale motivates trials. |

| Other pharmacologic/non-pharmacologic options (e.g., vitamin A, sodium citrate, insulin, theophylline, acupuncture) [47,59] | Heterogeneous mechanisms (epithelial regeneration; receptor modulation; neurometabolic effects) | Varies widely | Generally low-to-moderate evidence with heterogeneity; may be considered experimental or context-dependent. |

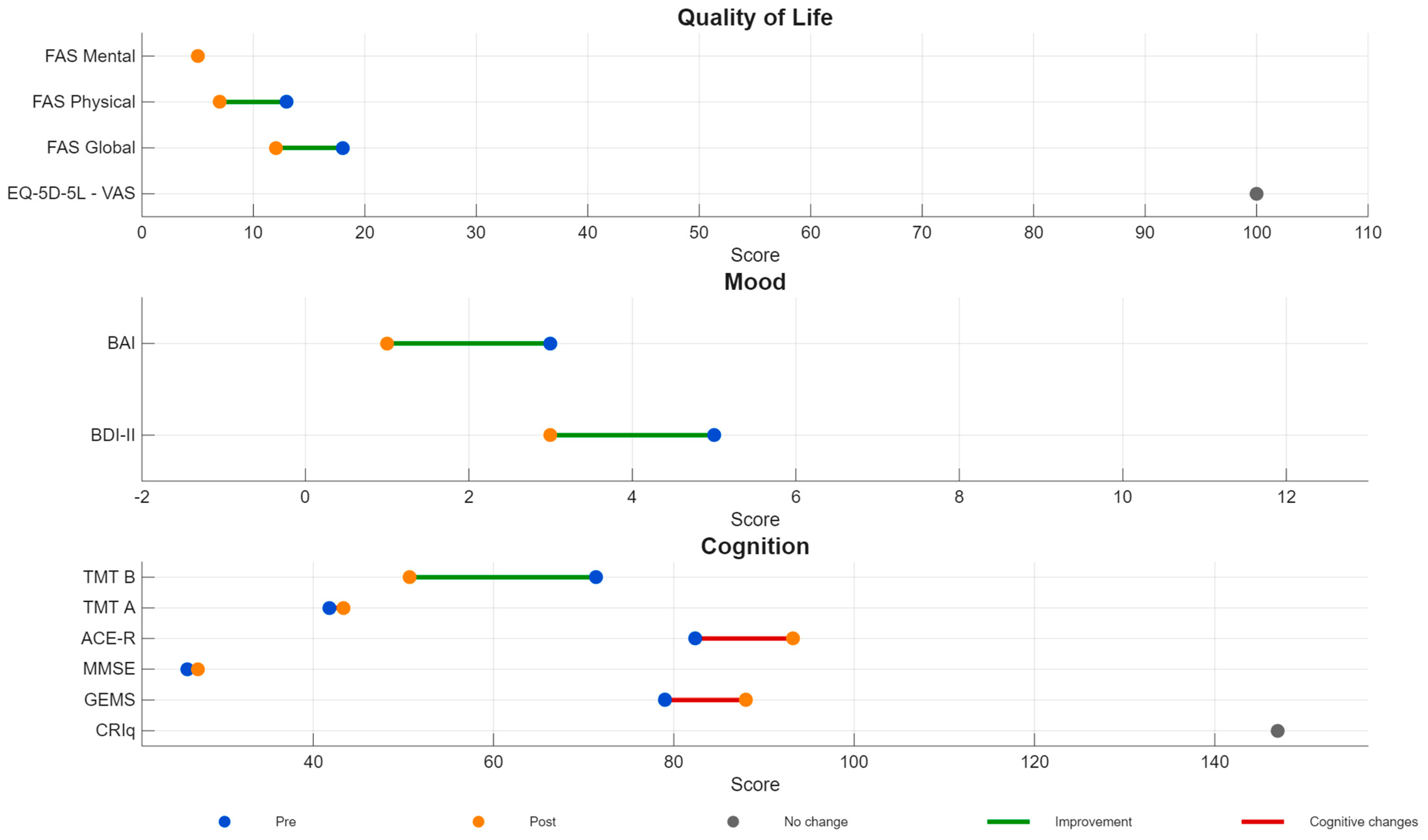

| Domain | Key Findings (Summary) | Suggested Assessment Targets | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory-specific quality of life [60] | Olfactory loss impacts daily life (eating, social, hazards) and can be severe for a subset of patients. | QOD (Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders), visual analogue scales; patient diary | Track treatment benefit beyond psychophysics; identify domains needing rehabilitation and counseling. |

| Mood and distress (depression/anxiety) [60] | Persistent OD is associated with higher depression/anxiety and distress, particularly post-COVID. | HADS/PHQ-9/GAD-7; clinical interview | Screen routinely; consider combined sensory rehabilitation + psychological support; monitor anhedonia. |

| Cognition (attention, executive function, memory) [60] | Associations between olfaction and cognition reported across populations; interventional evidence limited. | Global cognitive screen + domain tests (e.g., ACE-R/MMSE; TMT; verbal memory) | Use cognitive profiling to tailor interventions; investigate whether sensory recovery co-varies with cognition. |

| Eating behavior, nutrition and weight [60] | OD can alter food enjoyment, appetite, dietary choices and may contribute to weight change. | Dietary history; weight/BMI; eating behavior questionnaires (as available) | Provide dietary counseling and safety guidance; monitor involuntary weight loss. |

| Safety and hazard detection [60] | Reduced ability to detect smoke, gas leaks and spoiled food increases environmental risks. | Structured safety checklist; caregiver report | Implement compensatory strategies (alarms, labels, routines); provide written safety advice. |

| Social and hedonic functioning [60] | Olfaction contributes to social communication and hedonic experience; OD may reduce social engagement. | Patient-reported outcomes; social functioning scales (as available) | Psychoeducation; address avoidance and social withdrawal; consider partner/family counseling. |

| Measure | Score Range | Baseline (T0) | Post-Treatment (T36) | Direction of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

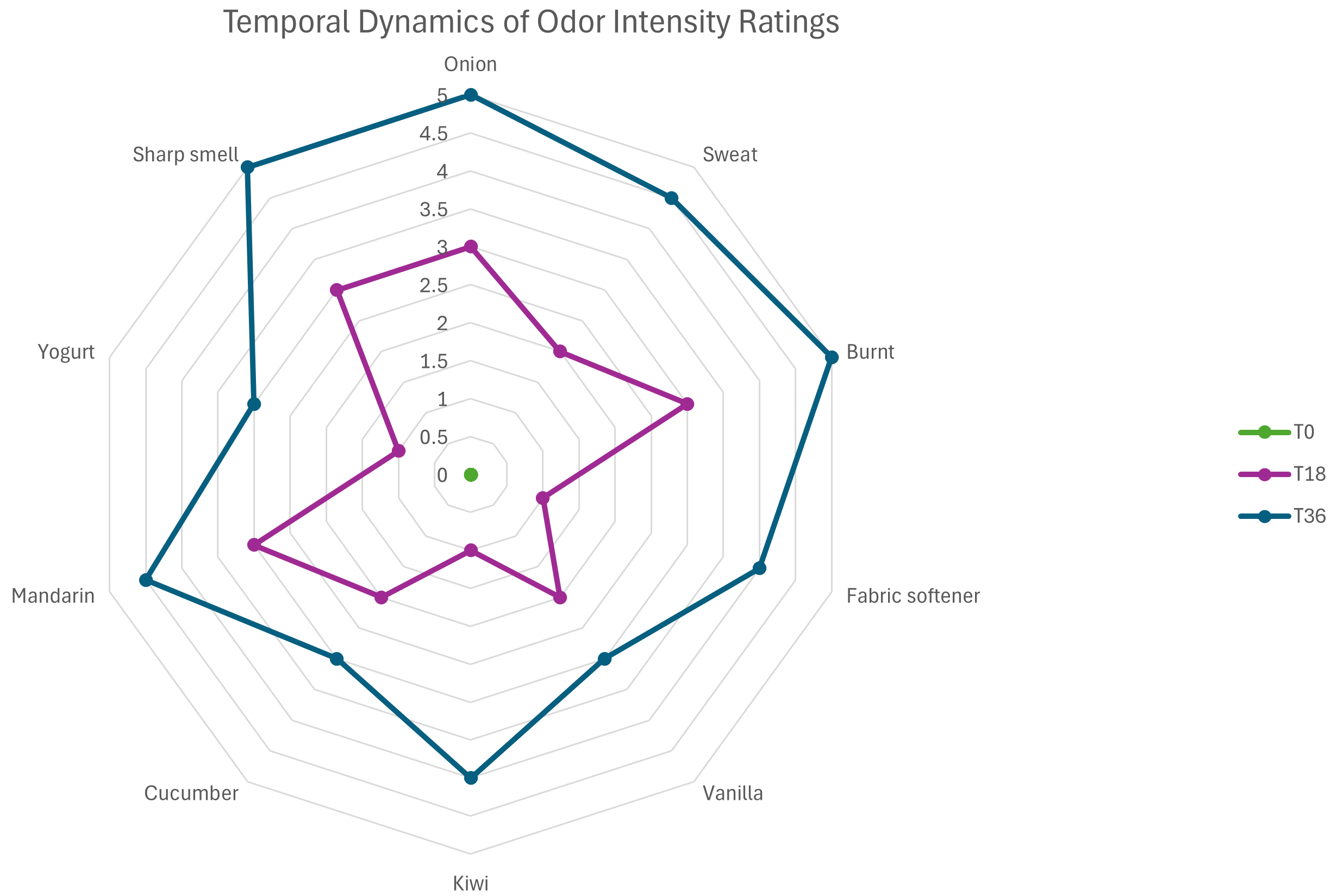

| Self-reported Mini Olfactory Questionnaire (Self-MOQ) [88] | 0–5 | 5 | 1 | ↓ Lower scores indicate better perceived olfactory function |

| Brief-IT-QOD—QOD-P (Parosmia) [89] | 0–12 | 1 | 0 | ↓ lower = fewer parosmia-related complaints |

| Brief-IT-QOD—QOD-NS (QoL burden) | 0–21 | 14 | 4 | ↓ lower = reduced olfactory-related QoL burden |

| Brief-IT-QOD—Total | 15 | 15 | 4 | ↓ lower = reduced overall burden |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Di Fazio, C.; Palermo, S. A Prefrontal Neuromodulation Route for Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Perspective Supported by Recovery During Left-DLPFC rTMS. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010099

Di Fazio C, Palermo S. A Prefrontal Neuromodulation Route for Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Perspective Supported by Recovery During Left-DLPFC rTMS. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Fazio, Chiara, and Sara Palermo. 2026. "A Prefrontal Neuromodulation Route for Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Perspective Supported by Recovery During Left-DLPFC rTMS" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010099

APA StyleDi Fazio, C., & Palermo, S. (2026). A Prefrontal Neuromodulation Route for Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction: A Perspective Supported by Recovery During Left-DLPFC rTMS. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010099