Prevalence and Imaging Correlates of Cerebral Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Registration

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- Population: Studies involving patients with ischemic stroke who did not undergo decompressive hemicraniectomy or other open neurosurgical intervention to avoid perfusion/metabolic changes unrelated to classical diaschisis.

- (2)

- Outcome/Definition: Studies must report diaschisis or provide sufficient information to derive diaschisis prevalence. For the purpose of this meta-analysis, we defined diaschisis as a remote reduction in perfusion, metabolism, or regional activity in a structurally intact brain region that is anatomically connected to the index lesion. Studies were eligible if they either (i) explicitly labeled the finding as diaschisis (e.g., CCD, thalamic, transhemispheric) or (ii) reported regional hypoperfusion/hypometabolism/reduced regional activation in a remote but structurally preserved region such that a reviewer could reasonably classify it as diaschisis according to the above definition.

- (3)

- Imaging modality: First, perfusion-based methods, including the following: (i) CT Perfusion, which measures cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV), and Time to maximum (Tmax), providing insight into hemodynamic changes associated with ischemia [14]. (ii) SPECT, which assesses regional perfusion by detecting the uptake of radiotracers, indirectly reflecting cerebral blood flow from a static perspective [15]. (iii) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (including ASL and DSC-PWI): ASL-MRI is a non-invasion perfusion technique that uses magnetically labeled arterial blood water as an endogenous tracer to assess CBF [16]. DSC-PWI is a dynamic MRI perfusion method that uses gadolinium contrast, measures perfusion parameters similar to CTP, but with higher spatial resolution [17]. Second, metabolism-based methods composed of (i) PET using, including 18FDG-PET or C15O2-PET [18], and (ii) Functional MRI [19].

- (4)

- Study design and data: Original research articles that report the numerator (number of patients with diaschisis) and denominator (total number of patients assessed or assessable) or provide sufficient data to derive prevalence.

- (5)

- Language and accessibility: Studies published in English (and other languages if data is complete) with full text available.

- (6)

- Although BOLD-fMRI does not directly quantify perfusion or metabolic rate, it reflects neurovascular coupling and regional neural activity. fMRI studies were therefore included only when they demonstrated reduced signal or activation in remote, structurally preserved regions consistent with functional depression secondary to anatomical disconnection. Pure connectivity-based analyses without evidence of regional suppression were excluded. This approach allowed complementary physiological measures to converge on a shared network-level construct.

- (1)

- Studies not focused on diaschisis or functional disconnection and do not provide extractable prevalence data or insufficient information to derive the numerator/denominator.

- (2)

- Patients undergoing decompressive hemicraniectomy or other open neurosurgical procedures, because postoperative perfusion/metabolic changes do not reflect classical diaschisis.

- (3)

- Studies involving non-ischemic conditions such as hemorrhagic stroke or brain tumors, or animal and in vitro studies.

- (4)

- Studies that only reported connectivity metrics (e.g., functional connectivity correlations) without reporting regional hypoperfusion/hypometabolism/reduced activation in a specific remote region.

- (5)

- Studies that describe regional low perfusion/metabolism, but the affected region is anatomically contiguous with the infarct (i.e., not “remote”), or where remote status/structural integrity cannot be established from the text/figures.

- (6)

- Studies where the low perfusion/metabolism is due to a separate primary pathology, unless diaschisis is explicitly demonstrated as secondary to an acute focal ischemic event.

- (7)

- Non-English-language publications without quantitative data; meeting abstracts; commentaries; letters; or case reports.

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

2.7. Follow-up Studies

2.8. Publication Bias Assessment

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

3.2. Study Population and Characteristics

3.3. Study Design and Geographic Distribution

3.4. Imaging Modalities and Types of Diaschisis

3.5. Occluded Vessel Types and Stroke Phases

3.6. NIHSS Scores and Follow-up Status

3.7. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

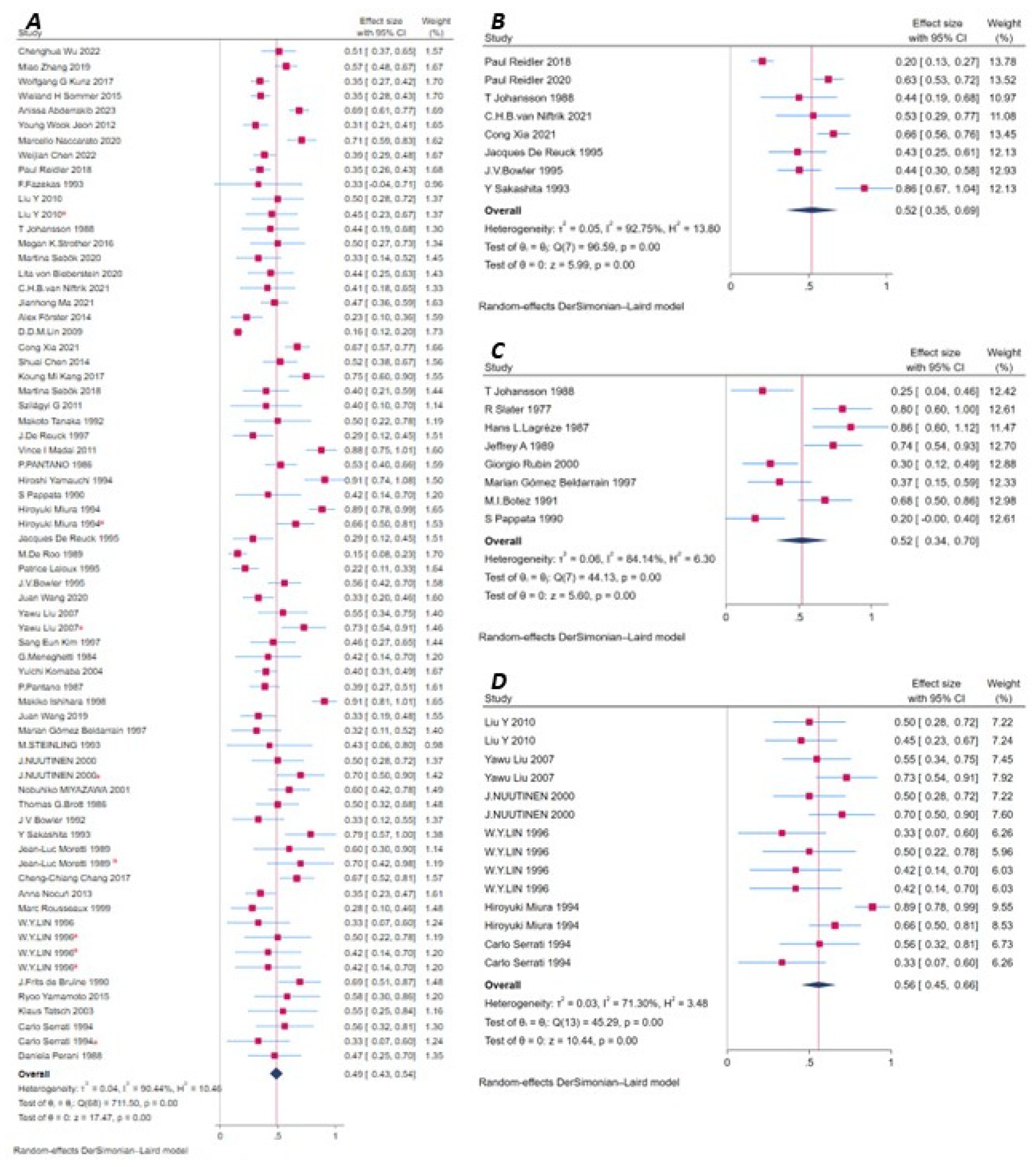

3.8. Meta-Analysis and Publication Bias by Imaging Modality

3.8.1. Perfusion-Based Methods

CT Perfusion (CTP)

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

Arterial Spin Labeling MRI (ASL MRI)

Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast Perfusion Imaging (DSC-PWI)

Xenon-Enhanced CT (XeCT)

3.8.2. Metabolism-Based and Functional Imaging Methods

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Functional MRI (fMRI)

3.9. Diaschisis Subtypes: CCD, ITD, and Other Types

3.9.1. Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis (CCD)

3.9.2. Ipsilateral Thalamic Diaschisis (ITD)

3.9.3. Other Types of Diaschisis

3.10. Study Design and Follow-up Heterogeneity

3.11. Influencing Factors Identified by Data-Driven Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Relevance, Imaging Strategy, and Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Finger, S.; Koehler, P.J.; Jagella, C. The Monakow Concept of Diaschisis: Origins and Perspectives. Arch. Neurol. 2004, 61, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera, E.; Tononi, G. Diaschisis: Past, present, future. Brain A J. Neurol. 2014, 137, 2408–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; Hu, C. Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis: Three Case Reports Imaging Using a Tri-Modality PET/CT-MR System. Medicine 2016, 95, e2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, J.C.; Levasseur, M.; Mazoyer, B.; Legault-Demare, F.; Mauguière, F.; Pappata, S.; Jedynak, P.; Derome, P.; Cambier, J.; Tran-Dinh, S.; et al. Thalamocortical diaschisis: Positron emission tomography in humans. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1992, 55, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, J.A.; Levine, R.L.; Lagreze, H.L.; Dulli, D.A.; Nickles, R.J.; Rowe, B.R. Evidence for Transhemispheric Diaschisis in Unilateral Stroke. Arch. Neurol. 1989, 46, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappata, S.; Mazoyer, B.; Tran Dinh, S.; Cambon, H.; Levasseur, M.; Baron, J.C. Effects of capsular or thalamic stroke on metabolism in the cortex and cerebellum: A positron tomography study. Stroke 1990, 21, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, P.; Lenzi, G.L.; Guidetti, B.; Di Piero, V.; Gerundini, P.; Savi, A.R.; Fazio, F.; Fieschi, C. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in patients with cerebral ischemia assessed by SPECT and 123I-HIPDM. Eur. Neurol. 1987, 27, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilágyi, G.; Vas, A.; Kerényi, L.; Nagy, Z.; Csiba, L.; Gulyás, B. Correlation between crossed cerebellar diaschisis and clinical neurological scales. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2012, 125, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guan, M.; Lian, H.J.; Ma, L.J.; Shang, J.K.; He, S.; Ma, M.M.; Zhang, M.L.; Li, Z.Y.; Wang, M.Y.; et al. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis detected by arterial spin-labeled perfusion magnetic resonance imaging in subacute ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2014, 23, 2378–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enager, P.; Gold, L.; Lauritzen, M. Impaired neurovascular coupling by transhemispheric diaschisis in rat cerebral cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004, 24, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.D.; Kleinman, J.T.; Wityk, R.J.; Gottesman, R.F.; Hillis, A.E.; Lee, A.W.; Barker, P.B. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in acute stroke detected by dynamic susceptibility contrast MR perfusion imaging. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009, 30, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, M.; Kumita, S.; Mizumura, S.; Kumazaki, T. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis: The role of motor and premotor areas in functional connections. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 1999, 9, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Review Articles, Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analysis, and the Updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Guidelines. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e934475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderrakib, A.; Ligot, N.; Torcida, N.; Sadeghi Meibodi, N.; Naeije, G. Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis Worsens the Clinical Presentation in Acute Large Vessel Occlusion. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 52, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, L.J.; Zhou, B.; Zu, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, W.Q.; Li, L.; Xu, J.R.; Chen, Z.A. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis after stroke detected noninvasively by arterial spin-labeling MR imaging. BMC Neurosci. 2020, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhou, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Tang, T.; Cai, Y.; Ju, S. Characterizing Diaschisis-Related Thalamic Perfusion and Diffusion After Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction. Stroke 2021, 52, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, L.; Yuan, K.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yan, C. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis after acute ischemic stroke detected by intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 43, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebök, M.; van Niftrik, C.H.B.; Piccirelli, M.; Bozinov, O.; Wegener, S.; Esposito, G.; Pangalu, A.; Valavanis, A.; Buck, A.; Luft, A.R.; et al. BOLD cerebrovascular reactivity as a novel marker for crossed cerebellar diaschisis. Neurology 2018, 91, e1328–e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niftrik, C.H.B.; Sebök, M.; Muscas, G.; Wegener, S.; Luft, A.R.; Stippich, C.; Regli, L.; Fierstra, J. Investigating the Association of Wallerian Degeneration and Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke With BOLD Cerebrovascular Reactivity. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 645157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2000. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Briel, M.; Walter, S.D.; Guyatt, G.H. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ 2010, 340, c117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024); Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Nuutinen, J.; Laakso, M.P.; Karonen, J.O.; Könönen, M.; Vanninen, E.; Kuikka, J.T.; Vanninen, R.L. Cerebellar apparent diffusion coefficient changes in patients with supratentorial ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2010, 122, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Karonen, J.O.; Nuutinen, J.; Vanninen, E.; Kuikka, J.T.; Vanninen, R.L. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in acute ischemic stroke: A study with serial SPECT and MRI. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007, 27, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutinen, J.; Kuikka, J.; Roivainen, R.; Vanninen, E.; Sivenius, J. Early serial SPET in acute middle cerebral artery infarction. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2000, 21, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, H.; Nagata, K.; Hirata, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Watahiki, Y.; Hatazawa, J. Evolution of crossed cerebellar diaschisis in middle cerebral artery infarction. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 1994, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.Y.; Kao, C.H.; Wang, P.Y.; Changlai, S.P.; Wang, S.J. Serial changes in regional blood flow in the cerebrum and cerebellum of stroke patients imaged by 99Tcm-HMPAO SPET. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1996, 17, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrati, C.; Marchal, G.; Rioux, P.; Viader, F.; Petit-Taboué, M.C.; Lochon, P.; Luet, D.; Derlon, J.M.; Baron, J.C. Contralateral cerebellar hypometabolism: A predictor for stroke outcome? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1994, 57, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M.; Moher, D. Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017); Higgins, J.P.T., Green, S., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, R.F. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat. Med. 1988, 7, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, J.; Hayward, K.S.; Kwakkel, G.; Ward, N.S.; Wolf, S.L.; Borschmann, K.; Krakauer, J.W.; Boyd, L.A.; Carmichael, S.T.; Corbett, D.; et al. Agreed definitions and a shared vision for new standards in stroke recovery research: The Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable taskforce. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 2017, 12, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Jiang, B.; Sun, L.; Hu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, X. A subtle connection between crossed cerebellar diaschisis and supratentorial collateral circulation in subacute and chronic ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cao, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhao, C.; Ma, Q.; Li, K.; Lu, J. Characteristics of cerebral perfusion and diffusion associated with crossed cerebellar diaschisis after acute ischemic stroke. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2020, 38, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.G.; Sommer, W.H.; Höhne, C.; Fabritius, M.P.; Schuler, F.; Dorn, F.; Othman, A.E.; Meinel, F.G.; von Baumgarten, L.; Reiser, M.F.; et al. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in acute ischemic stroke: Impact on morphologic and functional outcome. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 3615–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, W.H.; Bollwein, C.; Thierfelder, K.M.; Baumann, A.; Janssen, H.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Reiser, M.F.; Plate, A.; Straube, A.; von Baumgarten, L. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in patients with acute middle cerebral artery infarction: Occurrence and perfusion characteristics. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016, 36, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidler, P.; Mueller, F.; Stueckelschweiger, L.; Feil, K.; Kellert, L.; Fabritius, M.P.; Liebig, T.; Tiedt, S.; Puhr-Westerheide, D.; Kunz, W.G. Diaschisis revisited: Quantitative evaluation of thalamic hypoperfusion in anterior circulation stroke. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 27, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Whang, K.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, M.S. Dynamic CT Perfusion Imaging for the Detection of Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Korean J. Radiol. 2012, 13, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarato, M.; Ajčević, M.; Furlanis, G.; Lugnan, C.; Buoite Stella, A.; Scali, I.; Caruso, P.; Stragapede, L.; Ukmar, M.; Manganotti, P. Novel quantitative approach for crossed cerebellar diaschisis detection in acute ischemic stroke using CT perfusion. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 416, 117008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; He, S.; Song, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, F.; Tan, Z.; Yu, Y. Quantitative Ischemic Characteristics and Prognostic Analysis of Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis in Hyperacute Ischemic Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2022, 31, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidler, P.; Thierfelder, K.M.; Fabritius, M.P.; Sommer, W.H.; Meinel, F.G.; Dorn, F.; Wollenweber, F.A.; Duering, M.; Kunz, W.G. Thalamic Diaschisis in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Occurrence, Perfusion Characteristics, and Impact on Outcome. Stroke 2018, 49, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghetti, G.; Vorstrup, S.; Mickey, B.; Lindewald, H.; Lassen, N.A. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in ischemic stroke: A study of regional cerebral blood flow by 133Xe inhalation and single photon emission computerized tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1984, 4, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brott, T.G.; Gelfand, M.J.; Williams, C.C.; Spilker, J.A.; Hertzberg, V.S. Frequency and patterns of abnormality detected by iodine-123 amine emission CT after cerebral infarction. Radiology 1986, 158, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, T.; Söderborg, B.; Virgin, J. Cerebral infarctions studied by [123I]iodoamphetamine. Clinical aspects of the findings on single photon emission computed tomography and transmission computed tomography. Eur Neurol 1988, 28, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roo, M.; Mortelmans, L.; Devos, P.; Verbruggen, A.; Wilms, G.; Carton, H.; Wils, V.; Van den Bergh, R. Clinical experience with Tc-99m HM-PAO high resolution SPECT of the brain in patients with cerebrovascular accidents. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1989, 15, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruïne, J.F.; Limburg, M.; van Royen, E.A.; Hijdra, A.; Hill, T.C.; van der Schoot, J.B. SPET brain imaging with 201 diethyldithiocarbamate in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1990, 17, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, J.L.; Defer, G.; Cinotti, L.; Cesaro, P.; Degos, J.D.; Vigneron, N.; Ducassou, D.; Holman, B.L. “Luxury perfusion” with 99mTc-HMPAO and 123I-IMP SPECT imaging during the subacute phase of stroke. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1990, 16, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botez, M.I.; Léveillé, J.; Lambert, R.; Botez, T. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in cerebellar disease: Cerebello-cerebral diaschisis. Eur Neurol 1991, 31, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, J.V.; Costa, D.C.; Jones, B.E.; Steiner, T.J.; Wade, J.P. High resolution SPECT, small deep infarcts and diaschisis. J. R. Soc. Med. 1992, 85, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, F.; Payer, F.; Valetitsch, H.; Schmidt, R.; Flooh, E. Brain stem infarction and diaschisis. A SPECT cerebral perfusion study. Stroke 1993, 24, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakashita, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Kakuda, K.; Takamori, M. Hypoperfusion and vasoreactivity in the thalamus and cerebellum after stroke. Stroke 1993, 24, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinling, M.; Lecouffe, P.; Rousseaux, M.; Mazingue, A.; Huglo, D.; Duhamel, A.; Vergnes, R. Early and delayed distribution of N-isopropyl-[123I]-p-iodoamphetamine in haemorrhagic and ischaemic brain. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1993, 20, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowler, J.V.; Wade, J.P.; Jones, B.E.; Nijran, K.; Jewkes, R.F.; Cuming, R.; Steiner, T.J. Contribution of diaschisis to the clinical deficit in human cerebral infarction. Stroke 1995, 26, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloux, P.; Richelle, F.; Jamart, J.; De Coster, P.; Laterre, C. Comparative correlations of HMPAO SPECT indices, neurological score, and stroke subtypes with clinical outcome in acute carotid infarcts. Stroke 1995, 26, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Beldarrain, M.; García-Moncó, J.C.; Quintana, J.M.; Llorens, V.; Rodeño, E. Diaschisis and neuropsychological performance after cerebellar stroke. Eur. Neurol. 1997, 37, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Choi, C.W.; Yoon, B.W.; Chung, J.K.; Roh, J.H.; Lee, M.C.; Koh, C.S. Crossed-cerebellar diaschisis in cerebral infarction: Technetium-99m-HMPAO SPECT and MRI. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 1997, 38, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseaux, M.; Steinling, M. Remote regional cerebral blood flow consequences of focused infarcts of the medulla, pons and cerebellum. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 1999, 40, 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa, N.; Toyama, K.; Arbab, A.S.; Koizumi, K.; Arai, T.; Nukui, H. Evaluation of crossed cerebellar diaschisis in 30 patients with major cerebral artery occlusion by means of quantitative I-123 IMP SPECT. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2001, 15, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaba, Y.; Mishina, M.; Utsumi, K.; Katayama, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Mori, O. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in patients with cortical infarction: Logistic regression analysis to control for confounding effects. Stroke 2004, 35, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocuń, A.; Wojczal, J.; Szczepańska-Szerej, H.; Wilczyński, M.; Chrapko, B. Quantitative evaluation of crossed cerebellar diaschisis, using voxel-based analysis of Tc-99m ECD brain SPECT. Nucl. Med. Rev. Cent. East. Eur. 2013, 16, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, R.; Johkura, K.; Nakae, Y.; Tanaka, F. The mechanism of ipsilateral ataxia in lacunar hemiparesis: SPECT perfusion imaging. Eur. Neurol. 2015, 73, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Ku, C.H.; Chang, S.T. Postural asymmetry correlated with lateralization of cerebellar perfusion in persons with chronic stroke: A role of crossed cerebellar diaschisis in left side. Brain Inj. 2017, 31, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Suo, S.; Zu, J.; Zhu, W.; Pan, L.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Xu, J. Detection of Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis by Intravoxel Incoherent Motion MR Imaging in Subacute Ischemic Stroke. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perani, D.; Di Piero, V.; Lucignani, G.; Gilardi, M.C.; Pantano, P.; Rossetti, C.; Pozzilli, C.; Gerundini, P.; Fazio, F.; Lenzi, G.L. Remote effects of subcortical cerebrovascular lesions: A SPECT cerebral perfusion study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1988, 8, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.M.; Sohn, C.H.; Choi, S.H.; Jung, K.H.; Yoo, R.E.; Yun, T.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.W. Detection of crossed cerebellar diaschisis in hyperacute ischemic stroke using arterial spin-labeled MR imaging. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strother, M.K.; Buckingham, C.; Faraco, C.C.; Arteaga, D.F.; Lu, P.; Xu, Y.; Donahue, M.J. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis after stroke identified noninvasively with cerebral blood flow-weighted arterial spin labeling MRI. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016, 85, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, A.; Kerl, H.U.; Goerlitz, J.; Wenz, H.; Groden, C. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in acute isolated thalamic infarction detected by dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MRI. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.; Reivich, M.; Goldberg, H.; Banka, R.; Greenberg, J. Diaschisis with cerebral infarction. Stroke 1977, 8, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.; Levy, E.I.; Scarrow, A.M.; Firlik, A.D.; Karakus, A.; Wechsler, L.; Jungreis, C.A.; Yonas, H. Remote effects of acute ischemic stroke: A xenon CT cerebral blood flow study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2000, 10, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantano, P.; Baron, J.C.; Samson, Y.; Bousser, M.G.; Derouesne, C.; Comar, D. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis: Further studies. Brain 1986, 109, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrèze, H.L.; Levine, R.L.; Pedula, K.L.; Nickles, R.J.; Sunderland, J.S.; Rowe, B.R. Contralateral flow reduction in unilateral stroke: Evidence for transhemispheric diaschisis. Stroke 1987, 18, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Kondo, S.; Hirai, S.; Ishiguro, K.; Ishihara, T.; Morimatsu, M. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis accompanied by hemiataxia: A PET study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1992, 55, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, H.; Fukuyama, H.; Kimura, J.; Ishikawa, M.; Kikuchi, H. Crossed cerebellar hypoperfusion indicates the degree of uncoupling between blood flow and metabolism in major cerebral arterial occlusion. Stroke 1994, 25, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Reuck, J.; Decoo, D.; Lemahieu, I.; Strijckmans, K.; Goethals, P.; Van Maele, G. Ipsilateral thalamic diaschisis after middle cerebral artery infarction. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 134, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Reuck, J.; Decoo, D.; Lemahieu, I.; Strijckmans, K.; Goethals, P.; Van Maele, G. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis after middle cerebral artery infarction. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1997, 99, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madai, V.I.; Altaner, A.; Stengl, K.L.; Zaro-Weber, O.; Heiss, W.D.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, F.C.; Sobesky, J. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis after stroke: Can perfusion-weighted MRI show functional inactivation? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011, 31, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsch, K.; Koch, W.; Linke, R.; Poepperl, G.; Peters, N.; Holtmannspoetter, M.; Dichgans, M. Cortical hypometabolism and crossed cerebellar diaschisis suggest subcortically induced disconnection in CADASIL: An 18F-FDG PET study. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2003, 44, 862–869. [Google Scholar]

- Sebök, M.; van Niftrik, C.H.B.; Piccirelli, M.; Muscas, G.; Pangalu, A.; Wegener, S.; Stippich, C.; Regli, L.; Fierstra, J. Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis in Patients With Symptomatic Unilateral Anterior Circulation Stroke Is Associated With Hemodynamic Impairment in the Ipsilateral MCA Territory. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2021, 53, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bieberstein, L.; van Niftrik, C.H.B.; Sebök, M.; El Amki, M.; Piccirelli, M.; Stippich, C.; Regli, L.; Luft, A.R.; Fierstra, J.; Wegener, S. Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis Indicates Hemodynamic Compromise in Ischemic Stroke Patients. Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempinsky, W.H. Vascular and neuronal factors in diaschisis with focal cerebral ischemia. Res. Publ. Assoc. Res. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1966, 41, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naeije, G.; Rovai, A.; Destrebecq, V.; Trotta, N.; De Tiège, X. Anodal Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Reduces Motor and Cognitive Symptoms in Friedreich’s Ataxia: A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2023, 38, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Duan, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Effects of cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation on rehabilitation of upper limb motor function after stroke. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1044333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Gao, F.; Dai, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Exploring cerebellar transcranial magnetic stimulation in post-stroke limb dysfunction rehabilitation: A narrative review. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1405637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, T.; Bolar, D.S.; Achten, E.; Barkhof, F.; Bastos-Leite, A.J.; Detre, J.A.; Golay, X.; Günther, M.; Wang, D.J.J.; Haller, S.; et al. Current state and guidance on arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in clinical neuroimaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2023, 89, 2024–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Welsh, R.; Wang, Z. ASL MRI Denoising via Multi Channel Collaborative Low-Rank Regularization. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2024, 12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, C.; Feng, M.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Q.; et al. Radiomics features of DSC-PWI in time dimension may provide a new chance to identify ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 889090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijten, S.P.R.; Bos, D.; van Doormaal, P.J.; Goyal, M.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Roozenbeek, B.; van der Lugt, A.; Warnert, E.A.H. Cerebral blood flow quantification with multi-delay arterial spin labeling in ischemic stroke and the association with early neurological outcome. NeuroImage Clin. 2023, 37, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Václavík, D.; Volný, O.; Cimflová, P.; Švub, K.; Dvorníková, K.; Bar, M. The importance of CT perfusion for diagnosis and treatment of ischemic stroke in anterior circulation. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Sun, M.; Jiang, X.; Ma, C.; Xie, F.; Ma, X. Penumbra in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Curr. Neurovascular Res. 2021, 18, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashayeri Ahmadabad, R.; Tran, K.H.; Zhang, Y.; Kate, M.P.; Mishra, S.; Buck, B.H.; Khan, K.A.; Rempel, J.; Albers, G.W.; Shuaib, A. Utility of automated CT perfusion software in acute ischemic stroke with large and medium vessel occlusion. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, A.E.; Austin, M.C.; McKay, W.J.; Donnan, G.A. Sensitivity and specificity of 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT cerebral perfusion measurements during the first 48 h for the localization of cerebral infarction. Stroke 1997, 28, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masdeu, J.C.; Brass, L.M. SPECT imaging of stroke. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 1995, 5, S14–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisi, G.; Filice, S.; Scoditti, U. Arterial Spin Labeling MRI to Measure Cerebral Blood Flow in Untreated Ischemic Stroke. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 2019, 29, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verclytte, S.; Fisch, O.; Colas, L.; Vanaerde, O.; Toledano, M.; Budzik, J.F. ASL and susceptibility-weighted imaging contribution to the management of acute ischaemic stroke. Insights Into Imaging 2017, 8, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, L.; Lahiri, A.; Schollenberger, J. Recent progress in ASL. NeuroImage 2019, 187, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Delf, J.; Kasap, C.; Adair, W.; Rayt, H.; Bown, M.; Kandiyil, N. Feasibility of arterial spin labeling in evaluating high- and low-flow peripheral vascular malformations: A case series. BJR Case Rep. 2022, 8, 20210083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, M.M.; Lu, J.; Zaman, A.; Yang, H.; Cao, A.; Zeng, X.; Hassan, H.; Han, T.; Miao, X.; Shi, Y.; et al. Advancing ischemic stroke diagnosis and clinical outcome prediction using improved ensemble techniques in DSC-PWI radiomics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.S.; Rauch, G.M. Why emergency XeCT-CBF should become routine in acute ischemic stroke before thrombolytic therapy. Keio J. Med. 2000, 49, A25–A28. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, A.; Buchegger, F.; Seimbille, Y.; Ratib, O.; Garibotto, V. PET Molecular Imaging of Hypoxia in Ischemic Stroke: An Update. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 13, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerwaldt, A.E.; Straathof, M.; Oosterveld, W.; van Heijningen, C.L.; van Leent, M.M.; Toner, Y.C.; Munitz, J.; Teunissen, A.J.; Daemen, C.C.; van der Toorn, A.; et al. In vivo imaging of cerebral glucose metabolism informs on subacute to chronic post-stroke tissue status—A pilot study combining PET and deuterium metabolic imaging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2023, 43, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasireddi, A.; Schaefer, P.W.; Rohatgi, S. Metabolic Imaging of Acute Ischemic Stroke (PET, (1)Hydrogen Spectroscopy, (17)Oxygen Imaging, (23)Sodium MRI, pH Imaging). Neuroimaging Clin. North America 2024, 34, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodtmann, A.; Puce, A.; Darby, D.; Donnan, G. fMRI demonstrates diaschisis in the extrastriate visual cortex. Stroke 2007, 38, 2360–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Q.H.; Zhu, C.Z.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, X.N.; Long, X.Y.; Cao, Q.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Zang, Y.F. An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: Fractional ALFF. J. Neurosci. Methods 2008, 172, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofts, A.; Kelly, M.E.; Gibson, C.L. Imaging Functional Recovery Following Ischemic Stroke: Clinical and Preclinical fMRI Studies. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 2020, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, P.; Saur, D.; Zeisig, V.; Ettrich, B.; Patt, M.; Sattler, B.; Jochimsen, T.; Lobsien, D.; Meyer, P.M.; Bergh, F.T.; et al. Simultaneous PET/MRI in stroke: A case series. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 1421–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sub-Analysis | SMD | 95%CI | Diaschisis | Total | I2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 63 y | 0.56 | 0.47, 0.64 | 517 | 928 | 87.83% | <0.001 |

| Age ≥ 63 y | 0.51 | 0.44, 0.57 | 700 | 1487 | 84.46% | <0.001 |

| NIHSS < 8.8 | 0.52 | 0.33, 0.72 | 172 | 304 | 93.08% | <0.001 |

| NHISS ≥ 8.8 | 0.55 | 0.43, 0.67 | 382 | 744 | 91.96% | <0.001 |

| NOS < 7 | 0.55 | 0.44, 0.66 | 427 | 1043 | 93.72% | <0.001 |

| NOS ≥ 7 | 0.50 | 0.43, 0.56 | 955 | 1978 | 89.50% | <0.001 |

| CCD | 0.51 | 0.44, 0.57 | 1264 | 2833 | 92.65% | <0.001 |

| No CCD | 0.66 | 0.52, 0.80 | 118 | 188 | 73.00% | <0.001 |

| CTP | 0.49 | 0.40, 0.59 | 507 | 1066 | 90.31% | <0.001 |

| SPECT | 0.51 | 0.42, 0.59 | 432 | 959 | 87.64% | <0.001 |

| ASL MRI | 0.67 | 0.48, 0.86 | 130 | 181 | 86.47% | <0.001 |

| DSC-PWI | 0.28 | 0.09, 0.48 | 91 | 414 | 92.50% | 0.005 |

| XeCT | 0.55 | 0.06, 1.04 | 19 | 38 | 91.91% | 0.026 |

| PET | 0.61 | 0.49, 0.74 | 177 | 297 | 84.32% | <0.001 |

| fMRI | 0.39 | 0.28, 0.51 | 26 | 66 | 0.00% | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jia, Q.; Sheng, N.; Naeije, G. Prevalence and Imaging Correlates of Cerebral Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010050

Jia Q, Sheng N, Naeije G. Prevalence and Imaging Correlates of Cerebral Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Qi, Nannan Sheng, and Gilles Naeije. 2026. "Prevalence and Imaging Correlates of Cerebral Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010050

APA StyleJia, Q., Sheng, N., & Naeije, G. (2026). Prevalence and Imaging Correlates of Cerebral Diaschisis After Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010050