Functional Connectivity of Auditory, Motor, and Reward Networks at Rest and During Music Listening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Study 1: Foreground Music Group

2.2.2. Study 2: Background Music Group

2.3. fMRI Data Acquisition and Analysis

2.4. ROI-to-ROI Analyses

2.5. Seed-Based Connectivity Analyses

2.6. Graph Theory Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Ratings

3.1.1. Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

3.1.2. Study 2: Background Listening Group

3.2. ROI-to-ROI Analyses

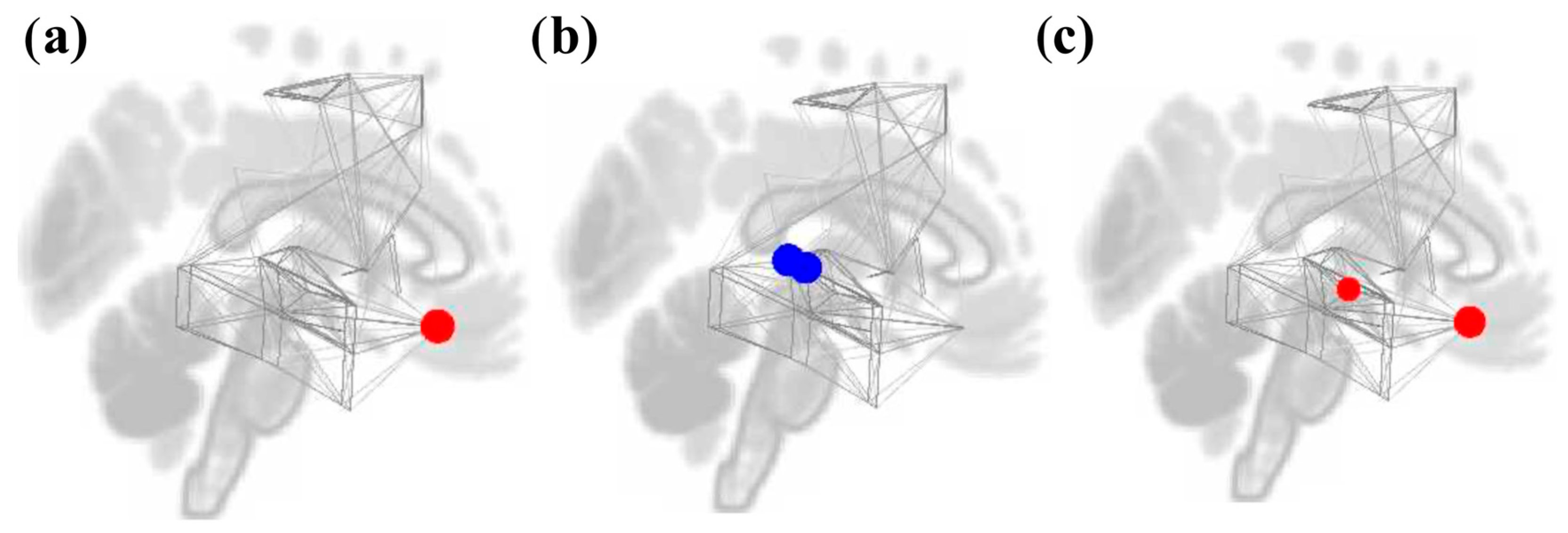

3.2.1. Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

3.2.2. Study 2: Background Listening Group

3.3. Seed-Based Connectivity Analyses

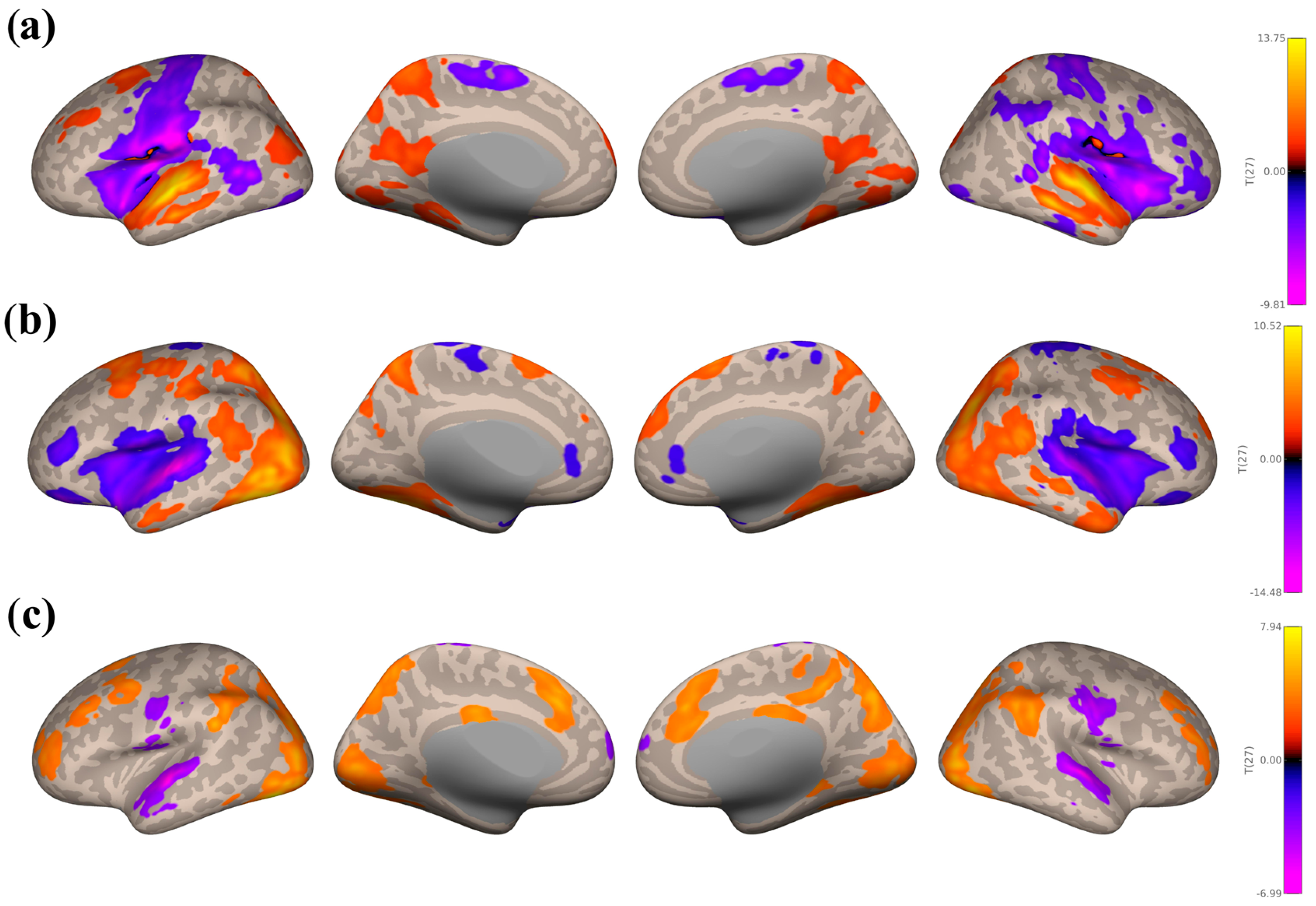

3.3.1. Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

3.3.2. Study 2: Background Listening Group

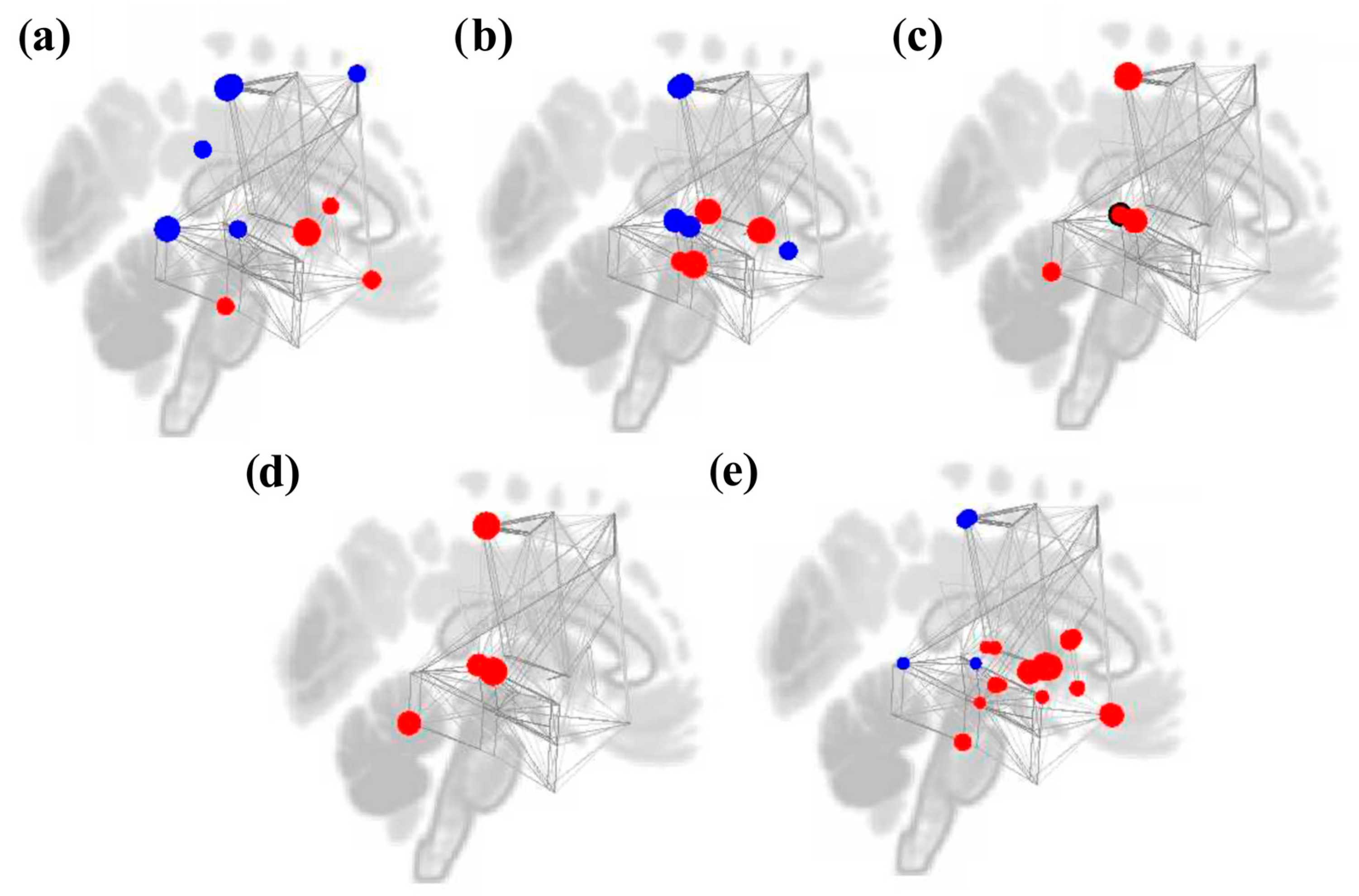

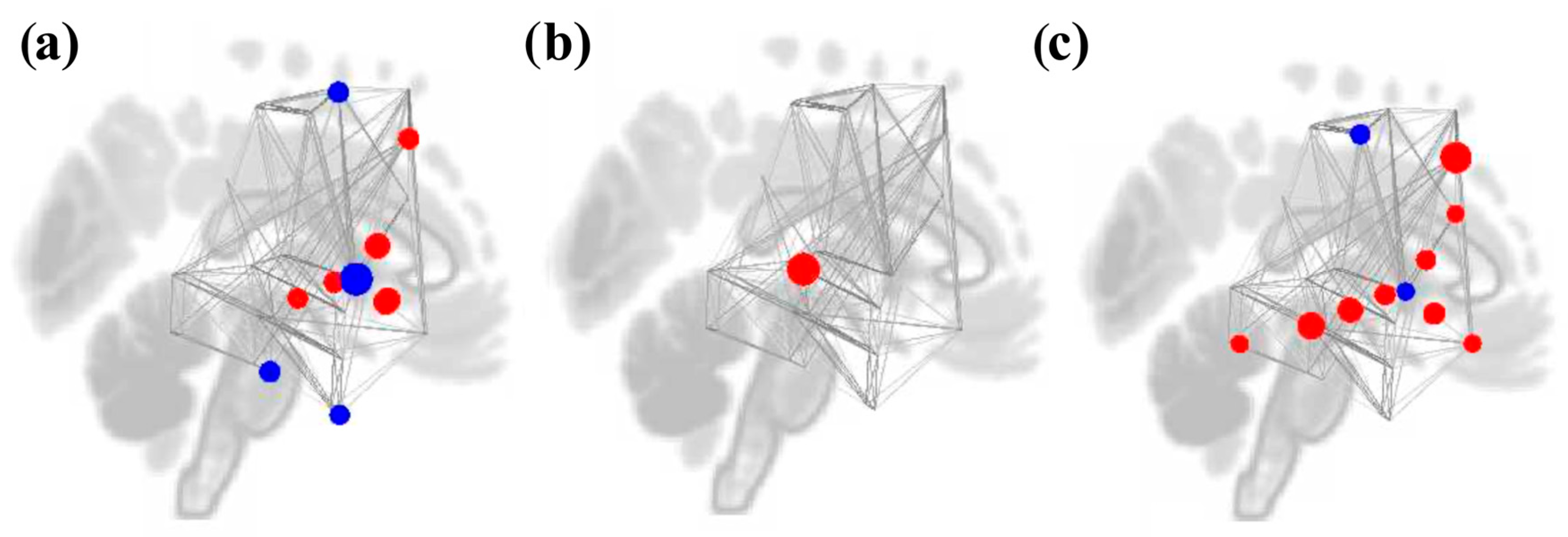

3.4. Graph Theory Analyses

3.4.1. Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

3.4.2. Study 2: Background Listening Group

4. Discussion

4.1. Music Enhances Intrinsic Auditory Network Connectivity

4.2. Context-Specific Motor and Reward Network Patterns During Music Listening

4.3. Network Analyses Support Reward System Integration

4.4. Rethinking the Role of Auditory Connectivity in Neurorehabilitation

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Beckman, E.; Broughton, M.; Bunzli, E.; Davidson, R.; Draper, G.; Fairley, S.; Farrell, C.; et al. How do music activities affect health and well-being? A scoping review of studies examining Psychosocial Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T.; Roy, A.R.K.; Welker, K.M. Music as an emotion regulation strategy: An examination of genres of music and their roles in emotion regulation. Psychol. Music 2017, 47, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, M.V.; La Marca, R.; Brönnimann, R.; Finkel, L.; Ehlert, U.; Nater, U.M. The effect of music on the Human Stress Response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, B.; Launay, J.; Dunbar, R.I.M. Silent disco: Dancing in synchrony leads to elevated pain thresholds and social closeness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2016, 37, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Mason-Bertrand, A.; Fancourt, D.; Baxter, L.; Williamon, A. How participatory music engagement supports mental well-being: A meta-ethnography. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1924–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvonen, A.J.; Särkämö, T.; Leo, V.; Tervaniemi, M.; Altenmüller, E.; Soinila, S. Music-based interventions in neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Perry, D.W.; Beckett, C.A.; Westbury, C.F.; Evans, A.C. Functional anatomy of musical processing in listeners with absolute pitch and relative pitch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3172–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Armony, J.L. Singing in the brain: Neural representation of music and voice as revealed by fmri. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 4913–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Chen, J.L.; Penhune, V.B. When the brain plays music: Auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Florian, I.A.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Bratu, B.G.; Glavan, L.A.; Bordeianu, A.; Dumitrascu, D.I.; Ciurea, A.V. Cognitive Crescendo: How Music Shapes the Brain’s Structure and Function. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, J.A.; Brett, M. Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Iversen, J.R. The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: The Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) hypothesis. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujioka, T.; Ross, B.; Trainor, L.J. Beta-Band Oscillations Represent Auditory Beat and Its Metrical Hierarchy in Perception and Imagery. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15187–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.-H.Z.; Creel, S.C.; Iversen, J.R. How do you feel the rhythm: Dynamic motor-auditory interactions are involved in the imagination of hierarchical timing. J. Neurosci. 2021, 42, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, E.E.; Kim, J.C.; Demos, A.P.; Roman, I.R.; Tichko, P.; Palmer, C.; Large, E.W. Musical neurodynamics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, P.; Tomic, S.T.; Haberman, J.M. Sensorimotor coupling in music and the psychology of the groove. J. Exp. Psychol. 2012, 141, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, O.; Kilchenmann, L.; Bechtold, T.; Hoesl, F. Groove in drum patterns as a function of both rhythmic properties and listeners’ attitudes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.E.; Witek, M.A.G.; Lund, T.; Vuust, P.; Penhune, V.B. The sensation of groove engages motor and reward networks. NeuroImage 2020, 214, 116768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, J.; Burunat, I.; Modroño, C.; González-Mora, J.L.; Plata-Bello, J. Music style not only modulates the auditory cortex, but also motor related areas. Neuroscience 2021, 457, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etani, T.; Miura, A.; Kawase, S.; Fujii, S.; Keller, P.E.; Vuust, P.; Kudo, K. A review of psychological and neuroscientific research on Musical Groove. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belden, A.; Quinci, M.A.; Geddes, M.; Donovan, N.J.; Hanser, S.B.; Loui, P. Functional organization of auditory and reward systems in aging. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 35, 1570–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belfi, A.M.; Loui, P. Musical anhedonia and rewards of music listening: Current advances and a proposed model. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2019, 1464, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluri, V.; Brattico, E.; Toiviainen, P.; Burunat, I.; Bogert, B.; Numminen, J.; Kliuchko, M. Musical expertise modulates functional connectivity of limbic regions during continuous music listening. Psychomusicol. Music. Mind Brain 2015, 25, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Fritz, T.; v Cramon, D.Y.; Müller, K.; Friederici, A.D. Investigating emotion with music: An fmri study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 27, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Martinez, M.J.; Parsons, L.M. Passive music listening spontaneously engages limbic and paralimbic systems. NeuroReport 2004, 15, 2033–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Herrero, E.; Dagher, A.; Farrés-Franch, M.; Zatorre, R.J. Unraveling the Temporal Dynamics of Reward Signals in Music-Induced Pleasure with TMS. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 3889–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpoor, V.N.; van den Bosch, I.; Kovacevic, N.; McIntosh, A.R.; Dagher, A.; Zatorre, R.J. Interactions between the nucleus accumbens and auditory cortices predict music reward value. Science 2013, 340, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Molina, N.; Mas-Herrero, E.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Zatorre, R.J.; Marco-Pallarés, J. Neural correlates of specific musical anhedonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E7337–E7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.E.; Ellis, R.J.; Schlaug, G.; Loui, P. Brain connectivity reflects human aesthetic responses to music. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Belden, A.; Hanser, S.B.; Geddes, M.R.; Loui, P. Resting-state connectivity of auditory and reward systems in alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Zatorre, R. State-dependent connectivity in auditory-reward networks predicts peak pleasure experiences to music. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loui, P.; Grent-’t-Jong, T.; Torpey, D.; Woldorff, M. Effects of attention on the neural processing of harmonic syntax in western music. Cogn. Brain Res. 2005, 25, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäncke, L.; Leipold, S.; Burkhard, A. The neural underpinnings of music listening under different attention conditions. NeuroReport 2018, 29, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, K.J.; Sampaio, G.; James, T.; Przysinda, E.; Hewett, A.; Spencer, A.E.; Morillon, B.; Loui, P. Rapid modulation in music supports attention in listeners with attentional difficulties. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcher, A.; Frommann, I.; Koppara, A.; Wolfsgruber, S.; Jessen, F.; Wagner, M. Face-name associative recognition deficits in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 56, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, O.; Markiewicz, C.J.; Blair, R.W.; Moodie, C.A.; Isik, A.I.; Erramuzpe, A.; Kent, J.D.; Goncalves, M.; DuPre, E.; Snyder, M.; et al. FMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 2018, 16, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Castanon, A. Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN; Hilbert Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Ashburner, J.; Frith, C.D.; Poline, J.B.; Heather, J.D.; Frackowiak, R.S. Spatial registration and normalization of images. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1995, 3, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettekoven, C.; Zhi, D.; Shahshahani, L.; Pinho, A.L.; Saadon-Grosman, N.; Buckner, R.L.; Diedrichsen, J. A hierarchical atlas of the human cerebellum for functional precision mapping. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinov, M.; Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. NeuroImage 2010, 52, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinci, M.A.; Belden, A.; Goutama, V.; Gong, D.; Hanser, S.; Donovan, N.J.; Geddes, M.; Loui, P. Longitudinal changes in auditory and reward systems following receptive music-based intervention in older adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathios, N.; Sachs, M.E.; Zhang, E.; Ou, Y.; Loui, P. Generating New Musical Preferences From Multilevel Mapping of Predictions to Reward. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 35, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupacher, J.; Hove, M.J.; Novembre, G.; Schütz-Bosbach, S.; Keller, P.E. Musical groove modulates motor cortex excitability: A TMS investigation. Brain Cogn. 2013, 82, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodal, H.P.; Osnes, B.; Specht, K. Listening to Rhythmic Music Reduces Connectivity within the Basal Ganglia and the Reward System. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.M.; Comstock, D.C.; Iversen, J.R.; Makeig, S.; Balasubramaniam, R. Cortical mu rhythms during action and passive music listening. J. Neurophysiol. 2022, 127, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Tan, X.; Zhang, J.; Xia, X. Deficits in Emotional Perception-Related Motor Cortical Excitability in Individuals With Trait Anxiety: A Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Study. Depress. Anxiety 2024, 2024, 5532347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajahan, P.M.; Glabus, M.F.; Gooding, P.A.; Shah, P.J.; Ebmeier, K.P. Reduced cortical excitability in depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1999, 174, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, F.; Pineda, J.; Cadenhead, K.S. Association of impaired EEG mu wave suppression, negative symptoms and social functioning in biological motion processing in first episode of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 130, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.C.; Enticott, P.G.; Hoy, K.E.; Thomson, R.H.; Fitzgerald, P.B. Reduced mu suppression and altered motor resonance in euthymic bipolar disorder: Evidence for a dysfunctional mirror system? Soc. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Guerrero, J.; Martínez-Orozco, H.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Santiago-Balmaseda, A.; Delgado-Minjares, K.M.; Pérez-Segura, I.; Baéz-Cortés, M.T.; Del Toro-Colin, M.A.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Arias-Carrión, O.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding Motor Impairments. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, R.; Mao, Z.-H. Progression of motor symptoms in parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2012, 28, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvà, D.; Favre, I.; Kraftsik, R.; Esteban, M.; Lobrinus, A.; Miklossy, J. Primary motor cortex involvement in alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1999, 58, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leodori, G.; De Bartolo, M.I.; Fabbrini, A.; Costanzo, M.; Mancuso, M.; Belvisi, D.; Conte, A.; Fabbrini, G.; Berardelli, A. The role of the motor cortex in tremor suppression in parkinson’s disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepert, J.; Bär, K.J.; Meske, U.; Weiller, C. Motor cortex disinhibition in alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, E.; Quoilin, C.; Derosiere, G.; Paço, S.; Jeanjean, A.; Duque, J. Corticospinal suppression underlying intact movement preparation fades in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 2396–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.L.; Story, K.M.; Harman, E.; Burns, D.S.; Bradt, J.; Edwards, E.; Golden, T.L.; Gold, C.; Iversen, J.R.; Habibi, A.; et al. Reporting guidelines for music-based interventions checklist: Explanation and elaboration guide. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1552659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenmüller, E.; Marco-Pallares, J.; Münte, T.F.; Schneider, S. Neural reorganization underlies improvement in stroke-induced motor dysfunction by music-supported therapy. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2009, 1169, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, M.A.G.; Clarke, E.F.; Wallentin, M.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Vuust, P. Syncopation, body-movement and pleasure in groove music. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Networks | ROIs | Beta | T (Df = 29) | p-FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Reward | FOrb r | 3.14 | 4.69 | 0.002931 |

| Betweenness Centrality | Auditory Auditory | pSTG l (Cluster 1) pSTG r (Cluster 1) | −0.02 −0.03 | −3.51 −3.48 | 0.038943 0.038943 |

| Global Efficiency | Reward Auditory | FOrb r pSTG r (Cluster 2) | 0.08 0.03 | 4.68 3.56 | 0.003016 0.032109 |

| Measures | Networks | ROIs | Beta | T (Df = 35) | p-FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Reward | Putamen l | 2.06 | 5.01 | 0.001186 |

| Auditory | toMTGr | −2.62 | −4.66 | 0.001186 | |

| Motor | PostCG l | −2.63 | −4.62 | 0.001186 | |

| Motor | PostCG r | −2.85 | −4.30 | 0.002133 | |

| Reward | Putamen r | 1.67 | 3.74 | 0.007853 | |

| Reward | FOrb l | 1.81 | 3.34 | 0.014927 | |

| Auditory | pSTGr (Cluster 1) | −2.14 | −3.28 | 0.014927 | |

| Reward | PCC | −1.71 | −3.27 | 0.014927 | |

| Auditory | pITG r | 1.81 | 3.25 | 0.014927 | |

| Motor | SFG r | −1.77 | −3.23 | 0.014927 | |

| Reward | Caudate l | 0.89 | 3.08 | 0.019980 | |

| Betweenness Centrality | Auditory | pMTG r | 0.03 | 4.06 | 0.011321 |

| Auditory | HG r | 0.03 | 3.84 | 0.011321 | |

| Reward | Putamen r | 0.03 | 3.78 | 0.011321 | |

| Reward | IC l | 0.04 | 3.68 | 0.011321 | |

| Reward | IC r | 0.04 | 3.61 | 0.011321 | |

| Auditory | pSTG l (Cluster 1) | −0.02 | −3.52 | 0.011801 | |

| Motor | PostCG l | −0.01 | −3.37 | 0.015142 | |

| Motor | PostCG r | −0.01 | −3.30 | 0.015694 | |

| Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | −0.02 | −3.25 | 0.015922 | |

| Reward | Putamen l | 0.03 | 2.87 | 0.036908 | |

| Auditory | pMTG l | 0.04 | 2.81 | 0.039231 | |

| Reward | NAcc l | −0.01 | −2.75 | 0.041886 | |

| Clustering Coefficient | Motor | PostCG r | 0.17 | 5.19 | 0.000743 |

| Auditory | pSTG l (Cluster 1) | 0.11 | 4.64 | 0.001540 | |

| Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | 0.10 | 3.79 | 0.010476 | |

| Motor | PostCG l | 0.12 | 3.59 | 0.013373 | |

| Reward | toITG l | 0.15 | 3.50 | 0.016786 | |

| Local Efficiency | Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | 0.08 | 4.76 | 0.001662 |

| Motor | PostCG r | 0.10 | 4.64 | 0.001662 | |

| Auditory | toITG l | 0.19 | 4.04 | 0.006698 | |

| Auditory | pSTG l (Cluster 1) | 0.07 | 3.85 | 0.006698 | |

| Global Efficiency | Reward | Putamen l | 0.11 | 6.02 | 0.000074 |

| Reward | Putamen r | 0.10 | 5.55 | 0.000134 | |

| Reward | Pallidum l | 0.09 | 5.31 | 0.000175 | |

| Reward | FOrb l | 0.05 | 5.03 | 0.00029 | |

| Reward | FOrb r | 0.05 | 4.76 | 0.000483 | |

| Reward | Pallidum r | 0.07 | 4.54 | 0.000734 | |

| Reward | Caudate l | 0.09 | 4.39 | 0.00095 | |

| Reward | IC l | 0.05 | 4.10 | 0.00185 | |

| Reward | Caudate r | 0.08 | 3.81 | 0.003603 | |

| Auditory | pITG l | 0.05 | 3.77 | 0.003603 | |

| Motor | PostCG r | −0.06 | −3.67 | 0.004384 | |

| Auditory | pSTG l (Cluster 2) | 0.07 | 3.62 | 0.004554 | |

| Motor | PostCG l | −0.05 | −3.55 | 0.00506 | |

| Reward | NAcc l | 0.08 | 3.38 | 0.007391 | |

| Auditory | HG r | 0.03 | 3.01 | 0.017139 | |

| Auditory | aSTG r | 0.03 | 2.99 | 0.017139 | |

| Auditory | HG l | 0.04 | 2.85 | 0.022859 | |

| Auditory | toMTGr | −0.02 | −2.76 | 0.026796 | |

| Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | −0.02 | −2.62 | 0.034589 | |

| Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 2) | 0.02 | 2.61 | 0.034589 | |

| Auditory | pMTG r | 0.02 | 2.58 | 0.03509 | |

| Reward | NAcc r | 0.07 | 2.53 | 0.038252 |

| Measures | Networks | ROIs | Beta | T (Df = 27) | p-FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Reward | IC r | −2.46 | −4.84 | 0.002273 |

| Reward | Caudate l | 1.12 | 3.78 | 0.012348 | |

| Reward | NAcc l | 0.57 | 3.7 | 0.012348 | |

| Reward | NAcc r | 0.41 | 3.69 | 0.012348 | |

| Reward | IC l | −1.83 | −3.45 | 0.018291 | |

| Auditory | pITG r | −1.35 | −3.19 | 0.022754 | |

| Reward | Pallidum r | 0.17 | 3.15 | 0.022754 | |

| Motor | SMA l | −1.34 | −3.14 | 0.022754 | |

| Motor | midFG l | 1.43 | 3.13 | 0.022754 | |

| Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 2) | 0.98 | 3.03 | 0.025982 | |

| Auditory | aITG r | −1.22 | −2.99 | 0.025982 | |

| Clustering Coefficient | Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | 0.13 | 4.48 | 0.004509 |

| Local Efficiency | Auditory | pSTG r (Cluster 1) | 0.10 | 4.17 | 0.010295 |

| Global Efficiency | Motor Auditory Auditory Reward Motor Reward Motor Reward Auditory Reward Reward Motor Reward | midFG l pMTG l (Cluster 1) pSTG r (Cluster 2) NAcc l midFG r Pallidum r PreCG l Caudate l toITG r IC r FOrb l ACC NAcc r | 0.03 0.02 0.09 0.05 0.02 0.04 −0.02 0.06 0.02 −0.02 0.03 0.02 0.05 | 4.73 4.12 3.81 3.35 3.25 3.19 −3.08 3.07 2.78 −2.72 2.71 2.7 2.68 | 0.003054 0.007821 0.012025 0.029272 0.029273 0.029273 0.029273 0.029273 0.046373 0.046373 0.046373 0.046373 0.046373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, K.Y.; Wang, J.; Kubit, B.M.; Parrish, C.; Loui, P. Functional Connectivity of Auditory, Motor, and Reward Networks at Rest and During Music Listening. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010015

Han KY, Wang J, Kubit BM, Parrish C, Loui P. Functional Connectivity of Auditory, Motor, and Reward Networks at Rest and During Music Listening. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Kai Yi (Kaye), Jinyu Wang, Benjamin M. Kubit, Corinna Parrish, and Psyche Loui. 2026. "Functional Connectivity of Auditory, Motor, and Reward Networks at Rest and During Music Listening" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010015

APA StyleHan, K. Y., Wang, J., Kubit, B. M., Parrish, C., & Loui, P. (2026). Functional Connectivity of Auditory, Motor, and Reward Networks at Rest and During Music Listening. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010015