Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Well-Being and Personal Values

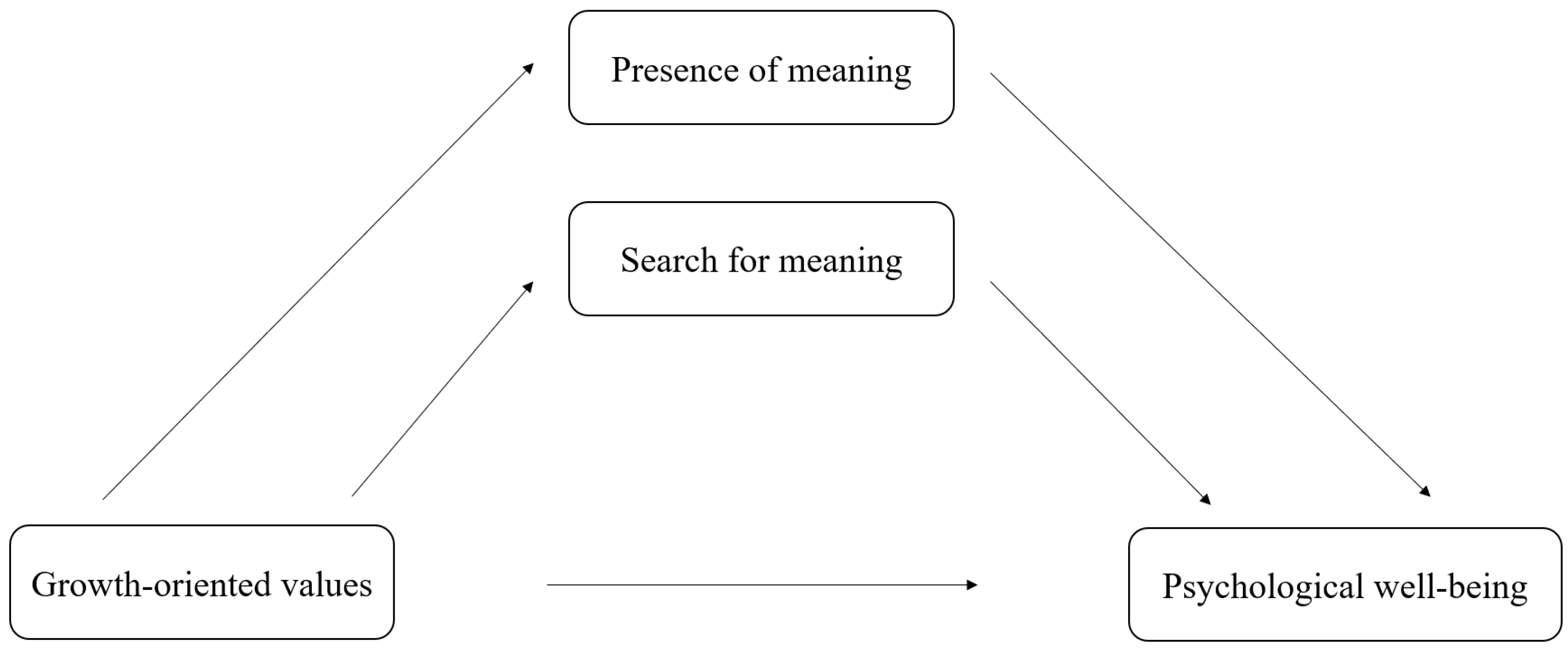

1.2. Potential Statistical Mediating Role of the Presence of Meaning and Search for Meaning in Life

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Psychological Well-Being Scales

2.3.2. Meaning in Life Questionnaire

2.3.3. Portrait Values Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial Correlations Among Variables

3.2. Analysis of Direct and Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Explaining Associations Between Psychological Well-Being and Personal Values

4.2. Role of Meaning in Life in Associations Between Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being

4.3. Limitations and Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 2007, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1948. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf/bd47/en/constitution-en.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, D.; Cieciuch, J. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza dobrostanu (Psychological Well-Being Scales) Carol Ryff. Rocz. Psychol. 2017, 20, 815–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Davidov, E.; Fischer, R.; Beierlein, C.; Ramos, A.; Verkasalo, M.; Lönnqvist, J.; Demirutku, K.; et al. Refining the theory of basic individual values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Torres, C.; Dirilen-Gumus, O.; Butenko, T. Value tradeoffs propel and inhibit behavior: Validating the 19 refined values in four countries. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowska, A.; Czerw, A. Values and well-being–how are individual values associated with subjective and eudaimonic well-being? Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 51, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Meaning in life. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 679–687. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Kashdan, T.B.; Sullivan, B.A.; Lorentz, D. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. J. Pers. 2008, 76, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D. Religijność a Jakość Życia w Perspektywie Mediatorów Psychospołecznych; Redakcja Uniwersytetu Opolskiego, Wydawnictwo Wydziału Teologicznego: Opole, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kossakowska, M.; Kwiatek, P.; Stefaniak, T. Sens w życiu. Polska wersja kwestionariusza MLQ (Meaning in Life Questionnaire). Psychol. Jak. Życia 2013, 12, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J.; Schwartz, S.H. Pomiar wartości w kołowym modelu Schwartza. In Metody Badania Emocji i Motywacji; Gasiul, H., Ed.; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; pp. 307–334. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowska, A.; Piotrowski, K. Two levels of personality: Temperament and values and their effects on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowska, A.; Kaczmarek, Ł.D. How healthy and unhealthy values predict hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: Dissecting value-related beliefs and behaviours. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L.; Roccas, S.; Oppenheim-Weller, S. Values and well-being. In Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life; Joseph, S., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H. Values priorities and subjective well-being: Direct relations and congruity effects. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Lönnqvist, J.E. Personal value priorities and life satisfaction in Europe: The moderating role of socioeconomic development. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besika, A.; Schooler, J.W.; Verplanken, B.; Mrazek, A.J.; Ihm, E.D. A relationship that makes life worth-living: Levels of value orientation explain differences in meaning and life satisfaction. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alandete, J. Does meaning in life predict psychological well-being? Eur. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 3, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D. Religijny system znaczeń i poczucie sensu życia jako predyktory eudajmonistycznego dobrostanu psychicznego u osób chorych na nowotwór. Stud. Psychol. Theor. Pract. 2014, 14, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, D. The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 2292–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.L. The meaning making model: A framework for understanding meaning, spirituality, and stress-related growth in health psychology. Eur. Health Psychol. 2013, 15, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

| Growth | Self-Protection | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal focus | Openness to change Self-direction—thought Self-direction—action Stimulation Hedonism | Self-enhancement Achievement Power—dominance Power—resources Face |

| Social focus | Self-transcendence Benevolence—dependability Benevolence—caring Universalism—concern Universalism—nature Universalism—tolerance | Conservation Security—personal Security—societal Tradition Conformity—rules Conformity—interpersonal Humility |

| Variables | M | SD | Psychological Well-Being | Presence of Meaning | Search for Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological well-being | 200.20 | 37.21 | - | ||

| 2. Presence of meaning | 22.24 | 7.59 | 0.74 ** | - | |

| 3. Search for meaning | 25.49 | 5.82 | 0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | - |

| 4. Openness to change | 55.58 | 9.55 | 0.44 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.39 ** |

| 5. Self-transcendence | 71.22 | 11.91 | 0.27 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.36 ** |

| 6. Self-enhancement | 45.24 | 9.07 | 0.08 (p = 0.26) | 0.11 (p = 0.12) | 0.11 (p = 0.13) |

| 7. Conservation | 71.62 | 13.68 | 0.10 (p = 0.16) | 0.17 (p = 0.02) | 0.26 ** |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | SE | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Openness to change ⭢ Presence of meaning | 0.32 *** | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 4.76 |

| Openness to change ⭢ Search for meaning | 0.39 *** | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 6.00 |

| Presence of meaning ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.68 *** | 2.87 | 3.82 | 0.24 | 13.78 |

| Search for meaning ⭢ Psychological well-being | −0.03 | −0.86 | 0.43 | 0.33 | −0.66 |

| Openness to change ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.23 *** | 0.51 | 1.29 | 0.20 | 4.60 |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| Indirect total effect | 0.21 | 0.42 | 1.24 | 0.21 | - |

| Openness to change ⭢ Presence of meaning ⭢ Well-being | 0.22 | 0.50 | 1.26 | 0.19 | - |

| Openness to change ⭢ Search for meaning ⭢ Well-being | −0.01 | −0.24 | 0.15 | 0.10 | - |

| Total effect | |||||

| Openness to change ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.44 *** | 1.21 | 2.19 | 0.25 | 6.83 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Presence of meaning | 0.28 *** | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 4.08 |

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Search for meaning | 0.36 *** | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 5.47 |

| Presence of meaning ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.72 *** | 3.03 | 4.03 | 0.25 | 13.97 |

| Search for meaning ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.02 | −0.53 | 0.80 | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 1.23 |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| Indirect total effect | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.16 | - |

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Presence of meaning ⭢ Well-being | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.91 | 0.14 | - |

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Search for meaning ⭢ Well-being | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.19 | 0.08 | - |

| Total effect | |||||

| Self-transcendence ⭢ Psychological well-being | 0.27 *** | 0.43 | 1.27 | 0.21 | 3.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmiel, M.; Kroplewski, Z. Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090930

Chmiel M, Kroplewski Z. Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090930

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmiel, Marianna, and Zdzisław Kroplewski. 2025. "Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090930

APA StyleChmiel, M., & Kroplewski, Z. (2025). Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090930