Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Prosody Perception: Evidence from English Interrogative Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Comparative Analysis of Interrogative Focus Prosody in English and Mandarin

1.2. Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Interrogative Focus Prosody Development

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli

- (1)

- Q1: Did Mona plan the vacation?

- A1: No, Mona ruined the vacation. (Matched.)

- A2: No, Mona ruined the vacation. (Matched.)

- A3: No, Mona ruined the vacation. (Mismatched.)

- A4: No, Mona ruined the vacation. (Mismatched.)

- (2)

- Q2: What did Anna eat?

- A1: Anna ate the pie. (Matched.)

- A2: Anna ate the pie. (Matched.)

- A3: Anna ate the pie. (Mismatched.)

- A4: Anna ate the pie. (Mismatched.)

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

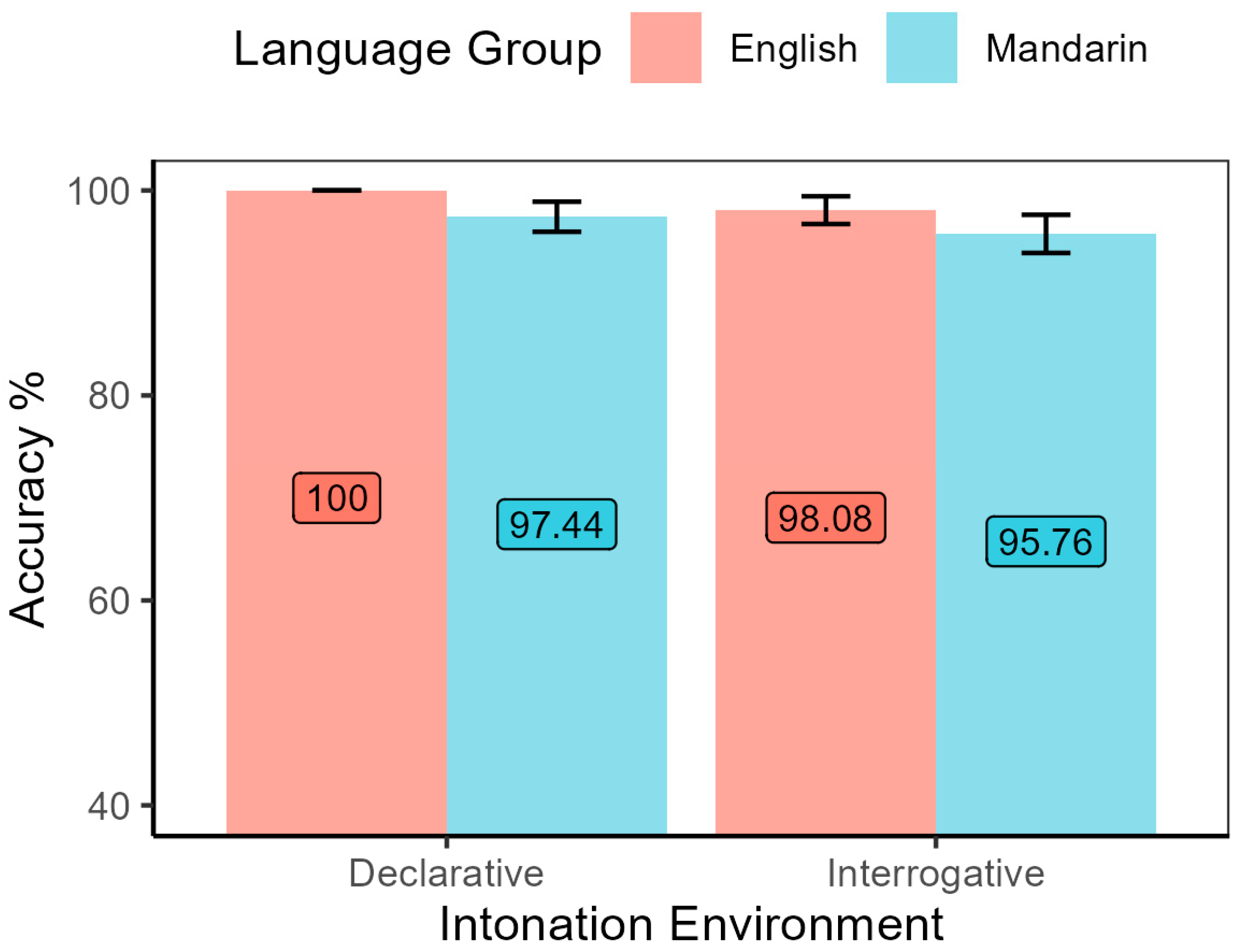

3.1. On-Focus Pitch Accents

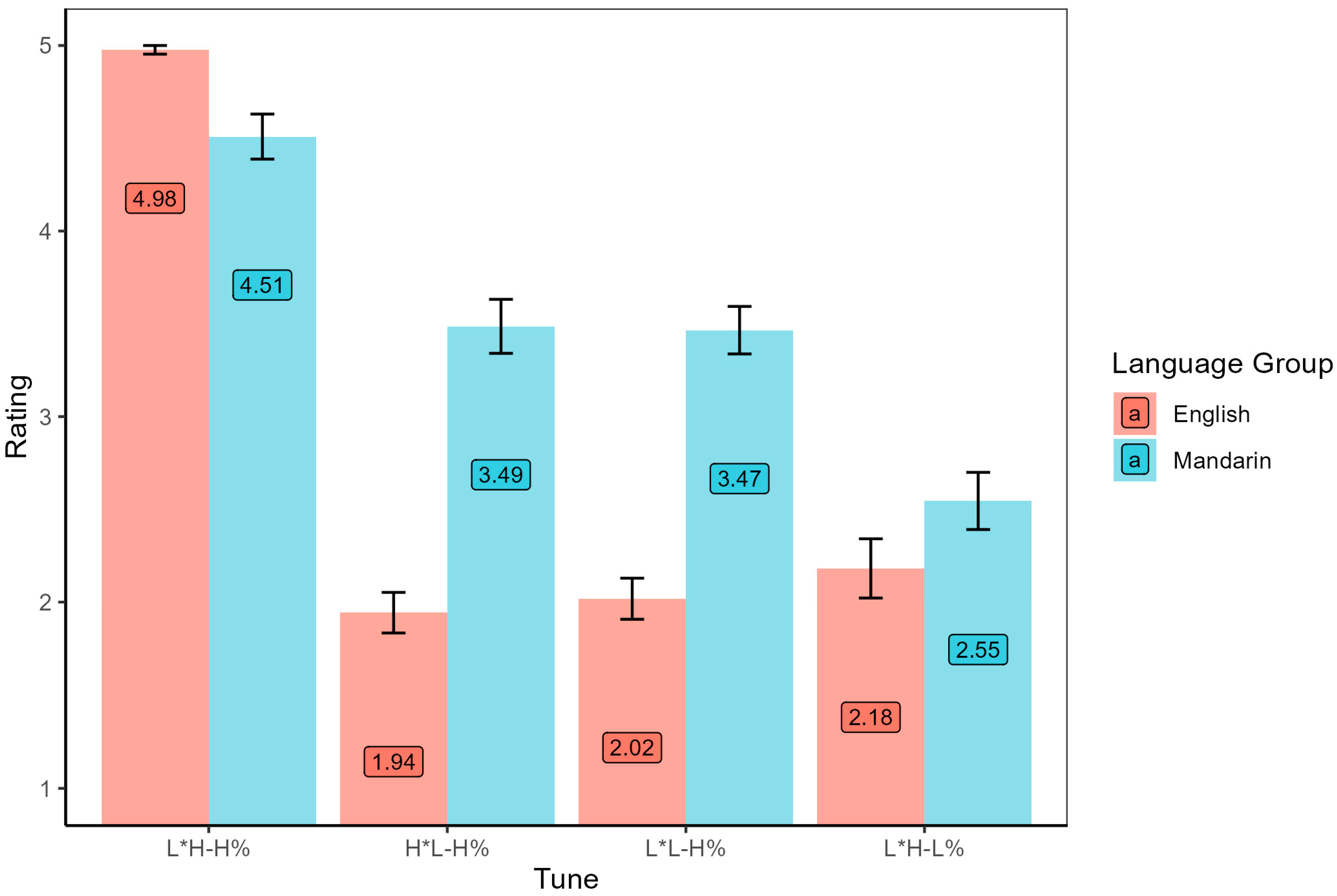

3.2. Naturalness Judgment

4. Discussion

4.1. Cross-Linguistic Influences on the Perception of Pitch Accents

4.2. Cross-Linguistic Influences on Edge Tone Perception

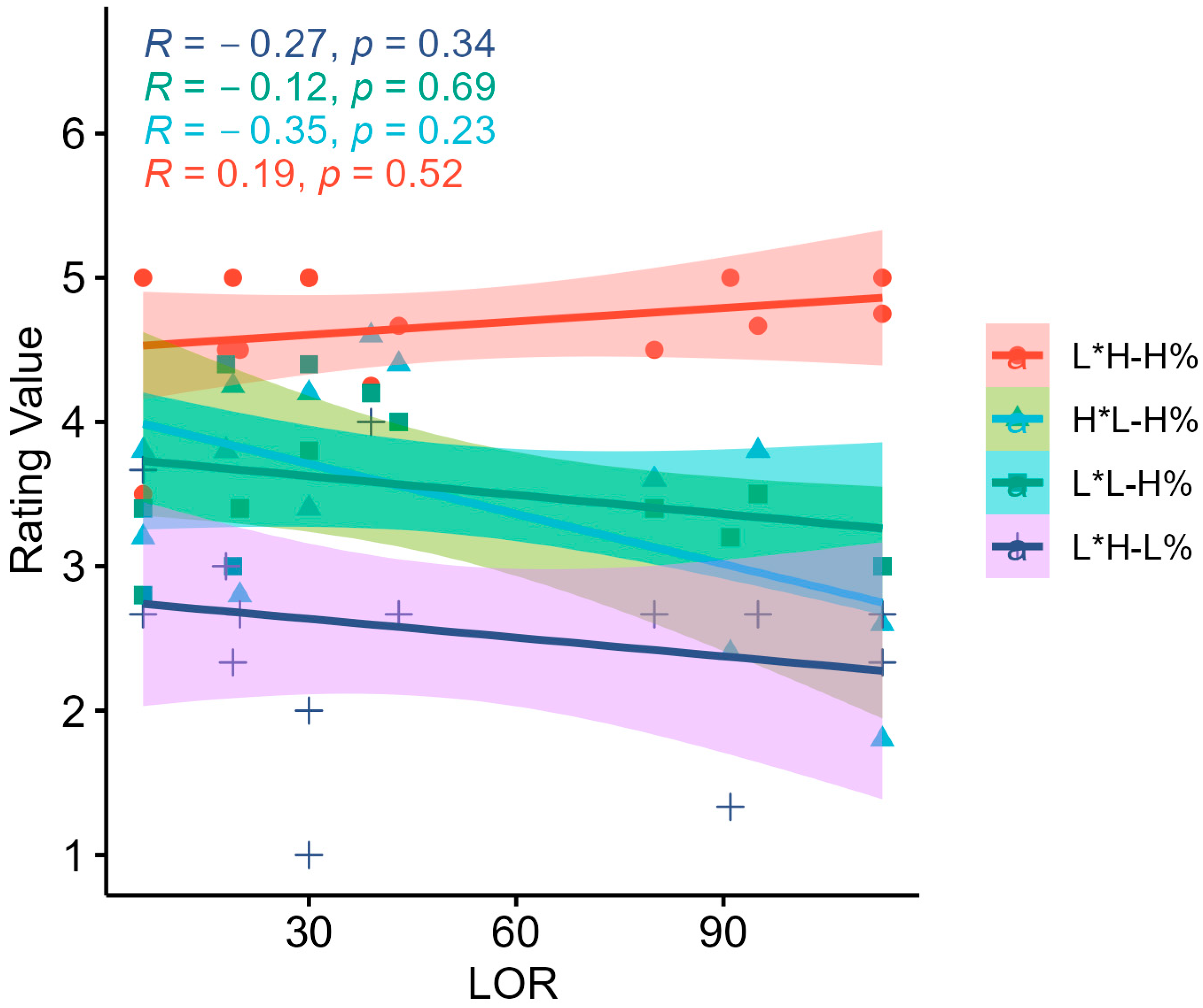

4.3. Role of L2 Experience in the Acquisition of Interrogative Focus Prosody

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Materials

| 1 | Roman women rarely marry. |

| 2 | Roman women rarely marry. |

| 3 | Roman women rarely marry. |

| 4 | Roman women rarely marry. |

| 5 | Roman women rarely marry. |

| 6 | Roman women rarely marry? |

| 7 | Roman women rarely marry? |

| 8 | Roman women rarely marry? |

| 9 | Roman women rarely marry? |

| 10 | Roman women rarely marry? |

| 11 | All men now run. |

| 12 | All men now run. |

| 13 | All men now run. |

| 14 | All men now run. |

| 15 | All men now run. |

| 16 | All men now run? |

| 17 | All men now run? |

| 18 | All men now run? |

| 19 | All men now run? |

| 20 | All men now run? |

| 1 | Match | 1 | s | Who ate the pie? | Anna ate the pie. |

| Match | 2 | s | Who ate the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 3 | s | Who ate the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 4 | s | Who ate the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| 2 | Match | 5 | v | What did Anna do with the pie? | Anna ate the pie. |

| Match | 6 | v | What did Anna do with the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 7 | v | What did Anna do with the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 8 | v | What did Anna do with the pie? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| 3 | Match | 9 | o | What did Anna eat? | Anna ate the pie. |

| Match | 10 | o | What did Anna eat? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 11 | o | What did Anna eat? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| Mismatch | 12 | o | What did Anna eat? | Anna ate the pie. | |

| 4 | Match | 13 | s | Who broke the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. |

| Match | 14 | s | Who broke the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 15 | s | Who broke the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 16 | s | Who broke the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| 5 | Match | 17 | v | What did Lenny do to the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. |

| Match | 18 | v | What did Lenny do to the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 19 | v | What did Lenny do to the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 20 | v | What did Lenny do to the vase? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| 6 | Match | 21 | o | What did Lenny break? | Lenny broke the vase. |

| Match | 22 | o | What did Lenny break? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 23 | o | What did Lenny break? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| Mismatch | 24 | o | What did Lenny break? | Lenny broke the vase. | |

| 7 | Match | 25 | v | Did Mona PLAN the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. |

| Match | 26 | v | Did Mona PLAN the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 27 | v | Did Mona PLAN the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 28 | v | Did Mona PLAN the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| 8 | Match | 29 | s | Did MARY ruin the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. |

| Match | 30 | s | Did MARY ruin the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 31 | s | Did MARY ruin the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 32 | s | Did MARY ruin the vacation? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| 9 | Match | 33 | o | Did Mona ruin the GATHERING? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. |

| Match | 34 | o | Did Mona ruin the GATHERING? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 35 | o | Did Mona ruin the GATHERING? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| Mismatch | 36 | o | Did Mona ruin the GATHERING? | No, Mona ruined the vacation. | |

| 10 | Match | 37 | s | Did RONAN call the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. |

| Match | 38 | s | Did RONAN call the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 39 | s | Did RONAN call the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 40 | s | Did RONAN call the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| 11 | Match | 41 | v | Did Laura EMAIL the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. |

| Match | 42 | v | Did Laura EMAIL the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 43 | v | Did Laura EMAIL the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 44 | v | Did Laura EMAIL the agent? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| 12 | Match | 45 | o | Did Laura call the MANAGER? | No, Laura called the agent. |

| Match | 46 | o | Did Laura call the MANAGER? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 47 | o | Did Laura call the MANAGER? | No, Laura called the agent. | |

| Mismatch | 48 | o | Did Laura cald the MANAGER? | No, Laura called the agent. |

| Situation | Materials | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The teacher knows that Mona finished her homework on time, but she wants to know if Anna also finished her homework on time. She says, | 1 | LHH | I know Mona finished her homework on time, but | did ANNA finish her homework on time? |

| 2 | LHL | I know Mona finished her homework on time, but | did ANNA finish her homework on time? | ||

| 3 | LLH | I know Mona finished her homework on time, but | did ANNA finish her homework on time? | ||

| 4 | HLH | I know Mona finished her homework on time, but | did ANNA finish her homework on time? | ||

| 2 | The manager knows that Joana went to New York by train, but now she wants to know if Emma also went to New York by train. She says, | 5 | LHH | I know Joana went to New York by train, but | did EMMA go to New York by train? |

| 6 | LHL | I know Joana went to New York by train, but | did EMMA go to New York by train? | ||

| 7 | LLH | I know Joana went to New York by train, but | did EMMA go to New York by train? | ||

| 8 | HLH | I know Joana went to New York by train, but | did EMMA go to New York by train? | ||

| 3 | The chef knows Leo made the cupcake by himself, but she wants to know if Manny also made the cupcake by himself. She says, | 9 | LHH | I know Leo made the cupcake by himself, but | did Manny make the cupcake by himself? |

| 10 | LHL | I know Leo made the cupcake by himself, but | did Manny make the cupcake by himself? | ||

| 11 | LLH | I know Leo made the cupcake by himself, but | did Manny make the cupcake by himself? | ||

| 12 | HLH | I know Leo made the cupcake by himself, but | did Manny make the cupcake by himself? | ||

| 4 | Mum knows Jason passed the drive test last week, but she wants to know if Nolan also passed the drive test last week. She says, | 13 | LHH | I know Jason passed the driving test last week, but | did Nolan pass the driving test last week? |

| 14 | LHL | I know Jason passed the driving test last week, but | did Nolan pass the driving test last week? | ||

| 15 | LLH | I know Jason passed the driving test last week, but | did Nolan pass the driving test last week? | ||

| 16 | HLH | I know Jason passed the driving test last week, but | did Nolan pass the driving test last week? | ||

| 5 | The agent knows that Lily hit the road sign by mistake, but she wants to know if Ella also hit it by mistake. She says, | 17 | LHH | I know Lily hit the road sign by mistake, but | did Ella hit the road sign by mistake? |

| 18 | LHL | I know Lily hit the road sign by mistake, but | did Ella hit the road sign by mistake? | ||

| 19 | LLH | I know Lily hit the road sign by mistake, but | did Ella hit the road sign by mistake? | ||

| 20 | HLH | I know Lily hit the road sign by mistake, but | did Ella hit the road sign by mistake? | ||

References

- Mennen, I.; de Leeuw, E. BEYOND SEGMENTS: Prosody in SLA. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2014, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, C.K.; Best, C.T. Cross-Language Perception of Non-Native Tonal Contrasts: Effects of Native Phonological and Phonetic Influences. Lang. Speech 2010, 53, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, C.K.; Best, C.T. Phonetic Influences on English and French Listeners’ Assimilation of Mandarin Tones to Native Prosodic Categories. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2014, 36, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, A.; Fletcher, J. The Autosegmental-Metrical Theory of Intonational Phonology. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Prosody; Gussenhhoven, C., Chen, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 78–95. ISBN 978-0-19-883223-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, M.; Onea, E. Focus Marking and Focus Interpretation. Lingua 2011, 121, 1651–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D.R. Intonational Phonology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tonhauser, J. Prosody and Meaning. In The Oxford Handbook of Experimental Semantics and Pragmatics; Cummins, C., Katsos, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 494–511. ISBN 978-0-19-879176-8. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, M.E.; Pierrehumbert, J.B. Intonational Structure in Japanese and English. Phonology 1986, 3, 255–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D.R. Intonational Phonology; Cambridge Studies in Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-521-47575-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert, J. The Phonology and Phonetics of English Intonation; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, K.E.; Beckman, M.E.; Pitrelli, J.F.; Ostendorf, M.; Wightman, C.W.; Price, P.; Pierrehumbert, J.B.; Hirschberg, J. ToBI: A Standard for Labeling English Prosody. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Banff, AB, Canada, 13–16 October 1992; Volume 2, pp. 867–870. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert, J.; Hirschberg, J. The Meaning of Intonational Contours in the Interpretation of Discourse. In Intentions in Communication; Cohen, P.R., Morgan, J., Pollack, M.E., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 271–312. ISBN 978-0-262-27054-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.-A. (Ed.) Prosodic Typology: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing; Oxford linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-924963-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, C.; Su, C. Where and How to Make an Emphasis?—L2 Distinct Prosody and Why. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing, Singapore, 12–14 September 2014; IEEE: Singapore, 2014; pp. 633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Chan, M.K.; Tseng, C.; Huang, T.; Lee, O.J.; Beckman, M.E. Towards a Pan-Mandarin System for Prosodic Transcription. In Prosodic Typology: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 230–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Li, Z. Focus and Boundary in Chinese Intonation. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Hong Kong, China, 17–21 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.-A. Prosodic Typology: By Prominence Type, Word Prosody, and Macro-Rhythm. In Prosodic Typology II: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 520–539. ISBN 978-0-19-956730-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama, M.; Jun, S.-A. Focus Realization in Japanese English and Korean English Intonation. UCLA Work. Pap. Phon. 1997, 94, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Gussenhoven, C. Emphasis and Tonal Implementation in Standard Chinese. J. Phon. 2008, 36, 724–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, Y. Parallel Encoding of Focus and Interrogative Meaning in Mandarin Intonation. Phonetica 2005, 62, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C. A Direct Realist View of Cross-Language Speech Perception. In Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues in Cross-Language Research; Strange, W., Ed.; York Press: York, UK, 1995; pp. 171–204. [Google Scholar]

- Best, C.T.; Bradlow, A.R.; Guion-Anderson, S.; Polka, L. Using the Lens of Phonetic Experience to Resolve Phonological Forms. J. Phon. 2011, 39, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.T.; Tyler, M.D. Nonnative and Second-Language Speech Perception: Commonalities and Complementarities. In Language Learning & Language Teaching; Bohn, O.-S., Munro, M.J., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 17, pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-90-272-1973-2. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J.E. The Production and Perception of Foreign Language Speech Sounds. In Human Communications and Its Disorders: A Review; Winitz, H., Ed.; Ablex Publishers: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 224–401. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J.E. Second Language Speech Learning: Theory, Findings, and Problems. Speech Percept. Linguist. Exp. Issues Cross-Lang. Res. 1995, 92, 233–277. [Google Scholar]

- Mennen, I. Beyond Segments: Towards a L2 Intonation Learning Theory. In Prosody and Language in Contact; Delais-Roussarie, E., Avanzi, M., Herment, S., Eds.; Prosody, Phonology and Phonetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 171–188. ISBN 978-3-662-45167-0. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.; Post, B. Second Language Acquisition of Intonation: Peak Alignment in American English. J. Phon. 2018, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayland, R.; Guerra, C.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y. English Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners. Languages 2019, 4, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, E.; Rosner, B.S.; García-Albea, J.E.; Zhou, X. Perception of English Intonation by English, Spanish, and Chinese Listeners. Lang. Speech 2003, 46, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Llebaria, M.; Wu, Z. Chinese-English Speakers’ Perception of Pitch in Their Non-Tonal Language: Reinterpreting English as a Tonal-Like Language. Lang. Speech 2021, 64, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S. Taiwanese EFL Learners’ Perception of English Word Stress. Concentric Stud. Linguist. 2010, 36, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, A.; Hirschberg, J.; Manis, K. Perception of English Prominence by Native Mandarin Chinese Speakers. In Proceedings of Speech Prosody; Columbia University Academic Commons: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Chinese EFL Learners’ Perception of English Prosodic Focus. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2023, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; ISCA; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T.M.; Munro, M.J. Putting Accent in Its Place: Rethinking Obstacles to Communication. Lang. Teach. 2009, 42, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.E. The Acquisition of English Focus Marking by Non-Native Speakers. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trofimovich, P.; Baker, W. Learning Second Language Suprasegmentals: Effect of L2 Experience on Prosody and Fluency Characteristics of L2 Speech. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2006, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennen, I. Second Language Acquisition of Intonation: The Case of Peak Alignment; Chicago Linguistic Society: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Piske, T.; MacKay, I.R.A.; Flege, J.E. Factors Affecting Degree of Foreign Accent in an L2: A Review. J. Phon. 2001, 29, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V.; Blumenfeld, H.K.; Kaushanskaya, M. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing Language Profiles in Bilinguals and Multilinguals. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2007, 50, 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chrabaszcz, A.; Winn, M.; Lin, C.Y.; Idsardi, W.J. Acoustic Cues to Perception of Word Stress by English, Mandarin, and Russian Speakers. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2014, 57, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Francis, A. The Weighting of Vowel Quality in Native and Non-Native Listeners’ Perception of English Lexical Stress. J. Phon. 2010, 38, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Llebaria, M.; Colantoni, L. L2 ENGLISH INTONATION: Relations between Form-Meaning Associations, Access to Meaning, and L1 Transfer. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2014, 36, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tian, X. Multiple Prosodic Meanings Are Conveyed through Separate Pitch Ranges: Evidence from Perception of Focus and Surprise in Mandarin Chinese. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 21, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutscheid, S.; Zahner-Ritter, K.; Leemann, A.; Braun, B. How Prior Experience with Pitch Accents Shapes the Perception of Word and Sentence Stress. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022, 37, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. On Production and Perception of Boundary Tone in Chinese Intonation. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Tonal Aspects of Languages (TAL 2004), Beijing, China, 28–31 March 2004; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J.E.; Bohn, O.-S.; Jang, S. Effects of Experience on Non-Native Speakers’ Production and Perception of English Vowels. J. Phon. 1997, 25, 437–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J. Mechanisms of Question Intonation in Mandarin. In Proceedings of the Chinese Spoken Language Processing, Singapore, 13–16 December 2006; Huo, Q., Ma, B., Chng, E.-S., Li, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zahner-Ritter, K.; Chen, Y.; Dehé, N.; Braun, B. The Prosodic Marking of Rhetorical Questions in Standard Chinese. J. Phon. 2022, 95, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Roseano, P.; Elvira-García, W. Dynamic Multi-Cue Weighting in the Perception of Spanish Intonation: Differences between Tonal and Non-Tonal Language Listeners. J. Phon. 2024, 102, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupoux, E.; Pallier, C.; Sebastian, N.; Mehler, J. A Destressing “Deafness” in French? J. Mem. Lang. 1997, 36, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupoux, E.; Sebastián-Gallés, N.; Navarrete, E.; Peperkamp, S. Persistent Stress ‘Deafness’: The Case of French Learners of Spanish. Cognition 2008, 106, 682–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P. High Is Not Just the Opposite of Low. J. Phon. 2015, 51, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, O.-S. Cross-Language and Second Language Speech Perception. In The Handbook of Psycholinguistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 213–239. ISBN 978-1-118-82951-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.; Kuo, G.; Kim, B. Phonology, Phonetics, and Signal-Extrinsic Factors in the Perception of Prosodic Prominence: Evidence from Rapid Prosody Transcription. J. Phon. 2020, 82, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, J.E. New Methods for Second Language (L2) Speech Research. In Second Language Speech Learning; Wayland, R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 119–156. ISBN 978-1-108-88690-1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.H.; Jun, S.-A. The Effect of Age on the Acquisition of Second Language Prosody. Lang. Speech 2011, 54, 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | n | Age Mean (SD) | LoR Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin native | 18 | 20.25 (2.08) | 3.66 (2.83) |

| English native | 18 | 20.41 (1.91) | / |

| No. | Pitch Accents | Phrase Accents | Boundary Tones | Canonical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L* | H- | H% | Yes |

| 2 | L* | H- | L% | No |

| 3 | L* | L- | H% | No |

| 4 | H* | L- | H% | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Kuang, C.; Chen, F. Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Prosody Perception: Evidence from English Interrogative Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15091000

Liu X, Chen X, Kuang C, Chen F. Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Prosody Perception: Evidence from English Interrogative Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15091000

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xing, Xiaoxiang Chen, Chen Kuang, and Fei Chen. 2025. "Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Prosody Perception: Evidence from English Interrogative Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15091000

APA StyleLiu, X., Chen, X., Kuang, C., & Chen, F. (2025). Cross-Linguistic Influences on L2 Prosody Perception: Evidence from English Interrogative Focus Perception by Mandarin Listeners. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15091000