Reinforcing Gaps? A Rapid Review of Innovation in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rapid Review Methodology

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

- ○

- Population: Adults or adolescents diagnosed with BPD (DSM-5, ICD-10/11, or equivalent standardised diagnostic criteria).

- ○

- Intervention: Any intervention deemed innovative (mutual agreement at selection based on treatment development knowledge), including but not limited to novel pharmacological agents, new psychotherapeutic modalities, digital interventions, neuromodulation techniques, or microbiome-based approaches.

- ○

- Publications dated between 1 January 2019 and 28 March 2025.

- ○

- Original empirical studies of the following designs: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, feasibility or pilot studies, and prospective or retrospective observational cohorts.

- ○

- Language: Full-text articles published in English or French.

- Exclusion Criteria

- ○

- Mixed-diagnosis populations without separate BPD results.

- ○

- Paediatric samples (<12 years).

- ○

- Non–peer-reviewed material (e.g., protocols, abstracts, editorials, letters, opinion pieces).

- ○

- Reviews without original data.

- ○

- Studies of other personality disorders without separate BPD analyses.

2.3. Search Strategy

- Keyword Development (Supplementary Materials)

- -

- Borderline personality disorder: Descriptors: “Borderline Personality Disorder” [Mesh] or keywords (titles abstracts): Borderline personality(ies), Borderline state(s)

- -

- Studies: Descriptors: “Clinical Study” [Publication Type] or keywords (titles abstracts): Clinical trial(s), Clinical study(ies), Randomised-control trial(s), Observational study(ies)

- Search Documentation and Management

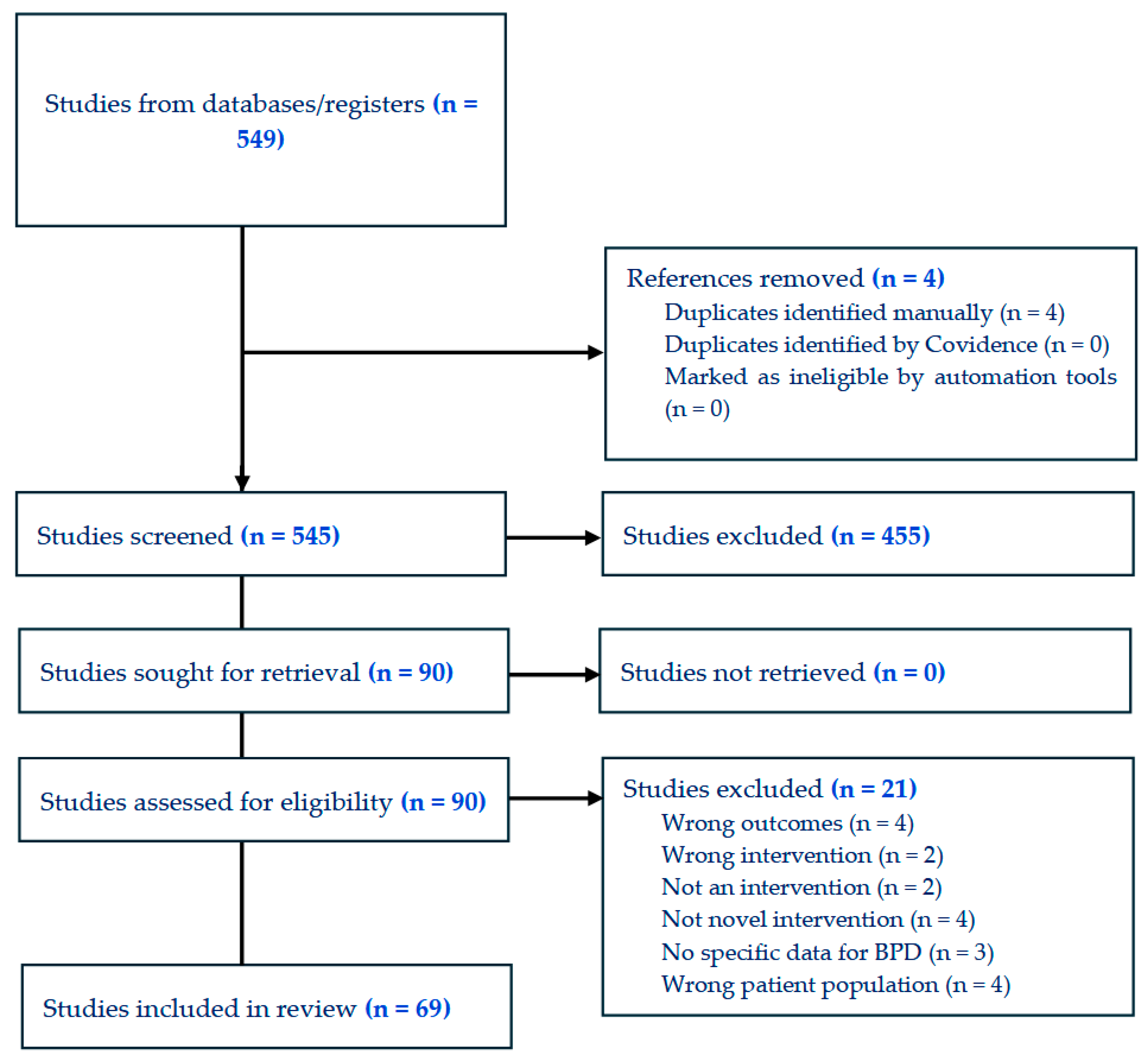

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

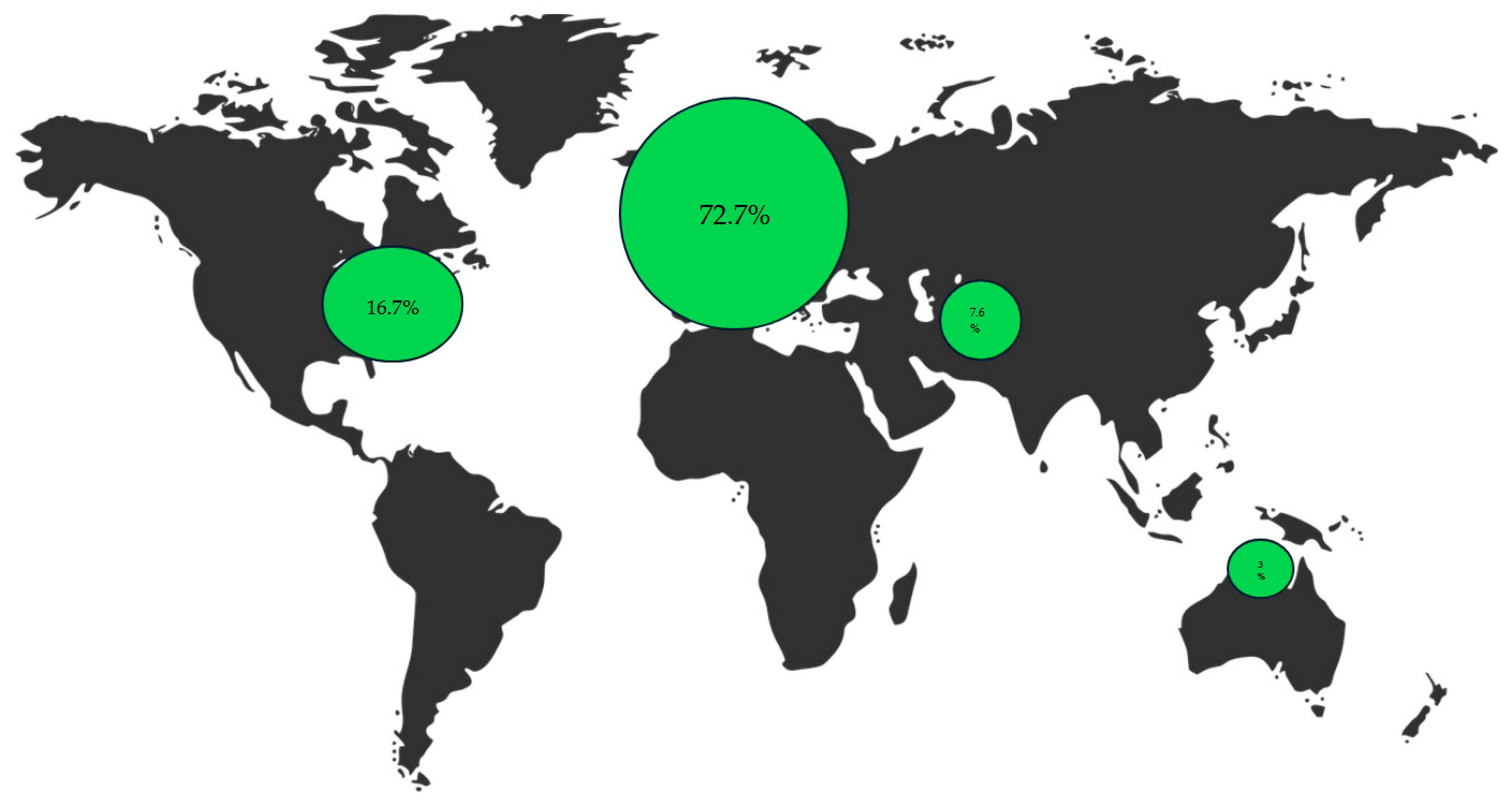

3.1. Sample

3.2. Cataloguing Therapeutic Innovations

3.3. Assessing Outcome Domains

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACT | Assertive Community Treatment |

| BPD | Borderline Personality Disorder |

| DBT | Dialectical behaviour therapy |

| EMDR | Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing |

| IRT | Imagery Rehearsal Therapy |

| MIT | Metacognitive Interpersonal Therapy |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| rTMS | repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| tDCS | transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5-TR ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M.; Heard, H.L.; Armstrong, H.E. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffers-Winterling, J.M.; Storebø, O.J.; Kongerslev, M.T.; Faltinsen, E.; Todorovac, A.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Sales, C.P.; Callesen, H.E.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Völlm, B.A.; et al. Psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: A focused systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2022, 221, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, F.; Fonagy, P.; Heim, N.; Kernberg, O.F.; Leweke, F.; Luyten, P.; Salzer, S.; Spitzer, C.; Steinert, C. Borderline personality disorder: A comprehensive review of diagnosis and clinical presentation, etiology, treatment, and current controversies. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenyer, B.F.S.; Townsend, M.L.; Lewis, K.; Day, N. To love and work: A longitudinal study of everyday life factors in recovery from borderline personality disorder. Personal. Ment. Health 2022, 16, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keepers, G.A.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Anzia, J.M.; Benjamin, S.; Lyness, J.M.; Mojtabai, R.; Servis, M.; Choi-Kain, L.; Nelson, K.J.; Oldham, J.M.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2024, 181, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohus, M.; Stoffers-Winterling, J.; Sharp, C.; Krause-Utz, A.; Schmahl, C.; Lieb, K. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2021, 398, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cailhol, L.; Pelletier, É.; Rochette, L.; Laporte, L.; David, P.; Villeneuve, É.; Paris, J.; Lesage, A. Prevalence, Mortality, and Health Care Use among Patients with Cluster B Personality Disorders Clinically Diagnosed in Quebec: A Provincial Cohort Study, 2001–2012. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjær, J.N.R.; Biskin, R.; Vestergaard, C.; Munk-JRgensen, P. All-Cause Mortality of Hospital-Treated Borderline Personality Disorder: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Pers. Disord. 2020, 34, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temes, C.M.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Zanarini, M.C. Deaths by Suicide and Other Causes Among Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Personality-Disordered Comparison Subjects over 24 Years of Prospective Follow-Up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Girardi, P.; Ruberto, A.; Tatarelli, R. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2005, 59, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, W.W.; Zhang, Y.H. Effects of dialectical behaviour therapy on reducing self-harming behaviours and negative emotions in patients with borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffers-Winterling, J.M.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Kongerslev, M.T.; Völlm, B.A.; Mattivi, J.T.; Faltinsen, E.; Todorovac, A.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Callesen, H.E.; Sales, C.P.; et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, CD012956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Zanarini, M.C. Comorbidity of Borderline Personality Disorder: Current Status and Future Directions. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 41, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Temes, C.M.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Reich, D.B.; Fitzmaurice, G.M. Description and prediction of time-to-attainment of excellent recovery for borderline patients followed prospectively for 20 years. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soloff, P.H.; Chiappetta, L. Time, Age, and Predictors of Psychosocial Outcome in Borderline Personality Disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2020, 34, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soloff, P.H.; Chiappetta, L. Suicidal Behavior and Psychosocial Outcome in Borderline Personality Disorder at 8-Year Follow-Up. J. Pers. Disord. 2017, 31, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedig, M.M.; Silverman, M.H.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Reich, D.B.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Zanarini, M.C. Predictors of suicide attempts in patients with borderline personality disorder over 16 years of prospective follow-up. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Tomás, I.; Ruiz, J.; Guilera, G.; Bados, A. Long-term clinical and functional course of borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.Y.Y.; Carter, P.E.; Bourke, M.E.; Grenyer, B.F.S. What Do Individuals With Borderline Personality Disorder Want From Treatment? A Study of Self-generated Treatment and Recovery Goals. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2019, 25, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Hein, K.E.; Glass, I.V.; Fitzmaurice, G.M. Sustained Symptomatic Remission and Recovery and Their Loss Among Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder and Patients With Other Types of Personality Disorders: A 24-Year Prospective Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 85, 57387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.; Palmier-Claus, J.; Branitsky, A.; Mansell, W.; Warwick, H.; Varese, F. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 141, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, C.; Batchelor, R.; Gumley, A.; Gajwani, R. Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Pers. Disord. 2023, 37, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Wagner, A.C.; Monson, C.M. Optimizing borderline personality disorder treatment by incorporating significant others: A review and synthesis. Personal. Disord. 2019, 10, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.R.; Townsend, M.L.; Grenyer, B.F.S. Parenting and personality disorder: An overview and meta-synthesis of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastrup, L.H.; Jennum, P.; Ibsen, R.; Kjellberg, J.; Simonsen, E. Societal costs of Borderline Personality Disorders: A matched-controlled nationwide study of patients and spouses. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Gazarian, D. Is research on borderline personality disorder underfunded by the National Institute of Health? Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliakis, E.A.; Sonley, A.K.I.; Ilagan, G.S.; Choi-Kain, L.W. Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder: Is Supply Adequate to Meet Public Health Needs? Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, E.; Dickens, G.L. Mental health services, care provision, and professional support for people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder: Systematic review of service-user, family, and carer perspectives. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujovic, M.; Bahr, C.; Riesbeck, M.; Benz, D.; Wingerter, L.; Deiß, M.; Margittai, Z.; Reinermann, D.; Plewnia, C.; Meisenzahl, E. Effects of intermittent theta burst stimulation add-on to dialectical behavioral therapy in borderline personality disorder: Results of a randomized, sham-controlled pilot trial. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Casellas-Pujol, E.; Pascual, J.C.; Schmidt, C.; Domínguez-Clavé, E.; Cebolla, A.; Alvear, D.; Muro, A.; Elices, M. Advancing the treatment of long-lasting borderline personality disorder: A feasibility and acceptability study of an expanded DBT-based skills intervention. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2022, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmus, B.; Marissen, M.A.E.; van den Berg, D.; Driessen, A.; Deen, M.L.; Slotema, K. Adding EMDR for PTSD at the onset of treatment of borderline personality disorder: A pilot study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2023, 79, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotema, C.W.; van den Berg, D.P.G.; Driessen, A.; Wilhelmus, B.; Franken, I.H.A. Feasibility of EMDR for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with personality disorders: A pilot study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1614822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayk, C.; Koch, N.; Stierand, J.; Timpe, F.; Ngo, H.-V.V.; Wilhelm, I.; Junghanns, K. Imagery rehearsal therapy for the treatment of nightmares in individuals with borderline personality disorder—A pilot study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 182, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehr, T.; Haeyen, S. Drawing your way out: Imagery rehearsal based art therapy (IR-AT) for post-traumatic nightmares in borderline personality disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, A.; Ecker, B. Memory reconsolidation in psychotherapy for severe perfectionism within borderline personality. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosic-Vasic, Z.; Schaitz, C.; Mayer, B.; Maier, A.; Connemann, B.; Kroener, J. Treating emotion dysregulation in patients with borderline personality disorder using imagery rescripting: A two-session randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 173, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarda-Blasco, A.; Elias, A.; Mendo-Cullell, M.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Forné, C.; Fernandez-Oñate, D.; Bossa, L.; Torrent, A.; Gallart-Palau, X.; Batalla, I. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendo-Cullell, M.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Forné, C.; Fernández-Oñate, D.; de Cortázar-Gracia, N.R.; Facal, C.; Torrent, A.; Palacios, R.; Pifarré, J.; Batalla, I. A pilot study of the efficacy of an adventure therapy programme on borderline personality disorder: A pragmatic controlled clinical trial. Personal. Ment. Health 2021, 15, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Varma, S.; Traynor, J.; Earle, E.A.; Vanstone, R.; Fulham, L.; Goenka, K.; Blumberg, M.J.; Wyatt, L.; Siegel, A.N.; et al. A pilot and feasibility study of Sage: A couple therapy for borderline personality disorder. Psychother Res. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegler, A.; Bumb, J.M.; Wisch, C.; Schuster, R.; Reinhard, I.; Hoffmann, S.; Frischknecht, U.; Enning, F.; Schmahl, C.; Kiefer, F.; et al. Does the Augmentation of Trauma Informed Hatha Yoga Increase the Effect of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Substance Use Disorders on Psychopathological Strain of Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Comorbid Substance Use Disorder? Results of a Quasi-Experimental Study. Eur. Addict. Res. 2023, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Harty, E. “Embodying opposites”-A case illustration of Dance Movement Therapy as an additional intervention in the treatment of co-morbid Borderline Personality Disorder and Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrini, G.; Carcione, A.; Lanfredi, M.; Nicolò, G.; Pedrini, L.; Corbo, D.; Magni, L.R.; Geviti, A.; Ferrari, C.; Gasparotti, R.; et al. Effect of metacognitive interpersonal therapy on brain structural connectivity in borderline personality disorder: Results from the CLIMAMITHE randomized clinical trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; CLIMAMITHE Study Group; Corbo, D.; Magni, L.R.; Pievani, M.; Nicolò, G.; Semerari, A.; Quattrini, G.; Riccardi, I.; Colle, L.; et al. Metacognitive interpersonal therapy in borderline personality disorder: Clinical and neuroimaging outcomes from the CLIMAMITHE study-A randomized clinical trial. Personal. Disord. 2023, 14, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamin, V.K.; AGothuey IGuenot, F. Compliant patients with borderline personality disorder non-responsive to one-year dialectical behavior therapy: Outcomes of a second year. J. Behaviroal Cogn. Ther. 2021, 31, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, A.; Warkentin, H.F.; Bierbrodt, J.; König, H.; Konnopka, A.; Pepic, A.; Peth, J.; Lambert, M.; Gallinat, J.; Karow, A.; et al. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in an assertive community treatment structure (ACT): Testing integrated care borderline (ICB) in a randomized controlled trial (RECOVER). Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2024, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Chamberlain, S.R. Cariprazine treatment of borderline personality disorder: A case report. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.; Ganasan, V.A.; Sulaiman, A.R.B. Brexpiprazole Attenuates Aggression, Suicidality and Substance Use in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Case Series. Medicina 2024, 60, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, B.; Brewer, C.; Chang, D.; Hobart, M.; Hefting, N.; McQuade, R.D.; Grant, J.E. A randomised study and an extension study of brexpiprazole in patients with borderline personality disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2024, 37, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.J.; Leeson, V.C.; Evans, R.; Barrett, B.; McQuaid, A.; Cheshire, J.; Sanatinia, R.; Lamph, G.; Sen, P.; Anagnostakis, K.; et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of clozapine for inpatients with severe borderline personality disorder (CALMED study): A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 12, 20451253221090832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, B.; Inch, K.M.; Kaschor, B.A. The use of buprenorphine/naloxone to treat borderline personality disorder: A case report. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2022, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadsadeghi, H.; Soleimannejad, M.; Ramazi, S.; Shalbafan, M.; Eftekhar Ardebili, M.; Vahabzadeh, G.; Ahmadirad, N.; Karimzadeh, F. Daily Oral Memantine Attenuated the Severity of Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogg, H.; Avram, M.; Müller, F.; Junghanns, K.; Borgwardt, S.; Zurowski, B. Ketamine as a Treatment Option for Severe Borderline Personality Disorder: A Case Report. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 43, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałuszko-Węgielnik, M.; Jakuszkowiak-Wojten, K.; Wilkowska, A.; Cubała, W.J. Short term ketamine treatment in patient with bipolar disorder with comorbidity with borderline personality disorder: Focus on impulsivity. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanicek, T.; Unterholzner, J.; Lanzenberger, R.; Naderi-Heiden, A.; Kasper, S.; Praschak-Rieder, N. Intravenous esketamine leads to an increase in impulsive and suicidal behaviour in a patient with recurrent major depression and borderline personality disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 23, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danayan, K.; Chisamore, N.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Meshkat, S.; Doyle, Z.; Mansur, R.; Phan, L.; Fancy, F.; Chau, E.; et al. Real world effectiveness of repeated ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression with comorbid borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 323, 115133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, S.K.; Choi, E.Y.; Shapiro-Thompson, R.; Dhaliwal, K.; Neustadter, E.; Sakheim, M.; Null, K.; Trujillo-Diaz, D.; Rondeau, J.; Pittaro, G.F.; et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of ketamine in Borderline Personality Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Moctezuma, A.R.; Reyes-López, J.V.; Rodríguez-Valdés, R.; Barbosa-Luna, M.; Ricardo-Garcell, J.; Espino-Cortés, M.; Hernández-Chan, N.; García-Noguez, L.; Roque-Roque, G.; Trejo-Cruz, G.; et al. Improvement in borderline personality disorder symptomatology after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex: Preliminary results. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 43, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feffer, K.; Lee, H.H.; Wu, W.; Etkin, A.; Demchenko, I.; Cairo, T.; Mazza, F.; Fettes, P.; Mansouri, F.; Bhui, K.; et al. Dorsomedial prefrontal rTMS for depression in borderline personality disorder: A pilot randomized crossover trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 301, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsberg, C.; Schecklmann, M.; Abdelnaim, M.A.; Weber, F.C.; Langguth, B.; Hebel, T. Treatment of depression and borderline personality disorder with 1 Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the orbitofrontal cortex—A pilot study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molavi, P.; Aziziaram, S.; Basharpoor, S.; Atadokht, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Salehinejad, M.A. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: A randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lisoni, J.; Miotto, P.; Barlati, S.; Calza, S.; Crescini, A.; Deste, G.; Sacchetti, E.; Vita, A. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assmann, N.; Jacob, G.; Schaich, A.; Berger, T.; Zindler, T.; Betz, L.; Borgwardt, S.; Arntz, A.; Fassbinder, E.; Klein, J.P. A digital therapeutic for people with borderline personality disorder in Germany (EPADIP-BPD): A pragmatic, assessor-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2025, 12, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, S.L.; Helweg-Jørgensen, S.; Langergaard, A.; Søndergaard, J.; Sørensen, S.S.; Mathiasen, K.; Lichtenstein, M.B.; Ehlers, L.H. Mobile Diary App Versus Paper-Based Diary Cards for Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder: Economic Evaluation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, V.; Fernández-Felipe, I.; Marco, J.H.; Grau, A.; Botella, C.; García-Palacios, A. “Family Connections”, a program for relatives of people with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Fam. Process. 2024, 63, 2195–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buronfosse, A.; Robin, M.; Speranza, M.; Duriez, P.; Silva, J.; Corcos, M.; Perdereau, F.; Younes, N.; Cailhol, L.; Gorwood, P.; et al. The impact of a telephone hotline on suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviors in patients with borderline personality disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1288195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Utz, A.; Walther, J.-C.; Schweizer, S.; Lis, S.; Hampshire, A.; Schmahl, C.; Bohus, M. Effectiveness of an Emotional Working Memory Training in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Proof-of-Principle Study. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.; Bick, D.; Biddle, L.; Borries, B.; Kandiyali, R.; Mgaieth, F.; Patel, V.; Rigby, J.; Seume, P.; Sadhnani, V.; et al. Perinatal emotional skills groups for women and birthing people with borderline personality disorder: Outcomes from a feasibility randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open 2024, 11, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.; Sinke, C.; Neumann, I.; Wollmer, M.A.; Kruger, T.H.C. Effects of glabellar botulinum toxin injections on resting-state functional connectivity in borderline personality disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 274, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollmer, M.A.; Neumann, I.; Jung, S.; Bechinie, A.; Herrmann, J.; Müller, A.; Wohlmuth, P.; Fournier-Kaiser, L.; Sperling, C.; Peters, L.; et al. Clinical effects of glabellar botulinum toxin injections on borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, S.; McMahon, J. Experiences of care by Australians with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, J.; Ilagan, G.S.; Iliakis, E.A.; Ren, B.; Schröder-Pfeifer, P.; Choi-Kain, L.W. What predicts psychosocial functioning in borderline personality disorder? Investigating the association with reflective functioning. Psychol Psychother. 2024, 97 (Suppl. S1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.Y.; Bourke, M.E.; Grenyer, B.F. Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Perspectives of Consumers, Clinicians, Family and Carers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.F.; Natoli, A.P. Clinical utility of categorical and dimensional perspectives on personality pathology: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Disord. 2019, 10, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, B.; Tsai, G.E. NMDA neurotransmission as a critical mediator of borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007, 32, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lisco, A.; Gallucci, A.; Fabietti, C.; Fornaroli, A.; Marchesi, C.; Preti, E.; Riva, P.; De Panfilis, C.; Lauro, L.J.R. Reduction of rejection-related emotions by transcranial direct current stimulation over right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in borderline personality disorder: A double-blind randomized pilot study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 79, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Amour, S.; Cailhol, L.; Ruocco, A.C.; Bernard, P. Acute Effect of Physical Exercise on Negative Affect in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pilot Study. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2022, 4, e7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenyer, B.F.S.; Lucas, S.; Barr, K.R.; Finch, A.; Denmeade, G.; Day, N.J.S. A randomized controlled trial of a peer and clinician led group program for borderline personality disorder. Psychother Res. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID | Study Design | Mean Age (SD) Intervention | Sex (Female %) Intervention | Psychotropic Drug (Y/N) Intervention | Neuromodulation (Y/N) Intervention | Psychotherapy (Y/N) Intervention | Digital Tools (Y/N) Intervention | Other: Specify Intervention | Duration (Weeks/Months) Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tinlin-Dixon 2024 | Case report | 68 | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 16 weeks + 4 follow-up sessions |

| Hansen 2022 | Case report | 26 | 100 | Y | N | N | N | N | 15 months |

| Mohajerin 2025 | Randomised controlled trial | 15.91 (0.98) | 65.2 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 weekly sessions |

| Reinsberg 2023 | Non-randomised experimental study | 24 | 86.7 | N | Y | N | N | N | 4 weeks |

| Sosic-Vasic 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 25.58 (5.7) | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 2 weeks |

| Kleindienst 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 months high-frequency + 3-month booster | ||

| Gabarda-Blasco 2024 | Non-randomised experimental study | 39.5 | 65.4 | N | N | Y | N | N | 14 weeks |

| Galuszko-Wegielnik 2023 | 26 | 100 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 weeks | |

| Molavi 2020 | Randomised controlled trial | 30.69 (5.01) | 50 | N | Y | N | N | N | 10 days |

| Back 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | 29 (7.9) | 100 | Y | N | N | N | N | one session |

| Danayan 2023 | Cohort study | 38.8 (14.6) | 58 | Y | N | N | N | N | 2 weeks |

| Mohajerin 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 27.16 (3.73) | 56.6 | N | N | Y | N | N | UP: ~42 months |

| Rothman 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | Y | N | N | N | N | 11 weeks (randomised phase) | ||

| Mendo-Cullell 2021 | Non-randomised experimental study | 41.5 | 50 | N | N | Y | N | N | 14 weeks |

| Fineberg 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | 32.1 (10.4) | 83.3 | Y | N | N | N | N | Single infusion (40 min) |

| Fitzpatrick 2025 | Cohort study | 31.31 (7.45) | 75 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 weeks |

| Moran 2024 | 29 (4) | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | Two 1 h preparatory + 12 weekly 2 h group sessions (~14 weeks) | |

| Steuwe 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | 30.82 (8.34) | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 10 weeks |

| Laursen 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | N | Y | N | 40 weeks at 2 sites; 12 months at 3 sites | ||

| Austin 2020 | Other: Mixed: qualitative and quantitative design | 28.9 (6.7) | 95 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 20.3 ± 6.3 weeks during DBT programme |

| Guillén 2022 | Non-randomised experimental study | 55.57 (8.9) | 61.5 | N | N | N | N | Family | 8 weeks |

| Rossi 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | 28.1 (7.4) | 86.5 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 months |

| Salvatore 2021 | Case report | mid-30s | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 18 months |

| Vaz 2020 | Case report | 20 | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 |

| Herpertz 2020 | Randomised controlled trial | 29.8 (9.5) | 66.7 | N | N | Y | N | N | 6 weeks |

| Rogg 2023 | Case report | 22 | 100 | Y | N | N | N | N | 9 months |

| Vanicek 2022 | Case report | 20 | 100 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 2 weeks |

| Bozzatello 2020 | Randomised controlled trial | 68.4 | N | N | Y | N | N | 10 months | |

| Bo 2022 | Case report | 16 | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 14 months |

| Calderón-Moctezuma 2020 | Randomised controlled trial | 24 (6.29) | 71.43 | N | Y | N | N | N | 3 weeks |

| Buronfosse 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | N | N | Hotline | 12 months | ||

| Sayk 2025 | Non-randomised experimental study | 29.9 (9.61) | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 8 weeks (8 sessions) |

| Hurtado-Santiago 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | 21.10 (4.3) | 90 | N | N | Y | N | N | 10 weekly group sessions (90 min) + 3 follow-up group sessions |

| Bozzatello 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | NR | NR | N | N | Y | N | N | 10 months |

| Bozzatello 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | 32.89 (10.64) | 71.4 | N | N | Y | N | N | 20 weeks |

| Dunand 2025 | Other: A multiple case study of clients’ experiences | 32 | 83.3 | N | N | Y | N | N | 5–20 months of IPS support (per client) |

| Guillén 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 56.89 (10.5) | 64.9 | N | N | N | N | Family | 12 weeks |

| Harty 2024 | Case report | NR | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 2 months |

| Dwyer 2025 | Randomised controlled trial | Y | N | N | N | N | 12 weeks | ||

| Kujovic 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 24.8 (5.9) | 88.2 | N | Y | Y | N | N | 4 weeks (20 sessions) |

| Schulze 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 28.75 (5.93) | 100 | N | N | N | N | Botulinium | Single administration; follow-up 4 weeks |

| Arntz 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | Y | N | N | 24 months | ||

| Alavi 2021 | Non-randomised experimental study | 80.8 | N | N | Y | Y | 15 weeks | ||

| Hilden 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | 31 (8.8) | 92 | N | N | Y | N | N | 20 weeks (20 sessions over 5 months) |

| Krause-Utz 2020 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | N | N | Cognitive training | 28 days (min 16, max 20 training days) | ||

| Schmeck 2023 | Non-randomised experimental study | 16.22 (1.57) | 91 | N | N | Y | N | N | 6–8 months |

| Klein 2021 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | N | Y | N | 12 months | ||

| Quattrini 2025 | Randomised controlled trial | 28 (8) | 91 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 months |

| Chanen 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | Y | N | N | Up to 16 sessions (weekly) or until 6-week nonattendance | ||

| Kehr 2024 | Case report | 40 | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 8 sessions over 2 months |

| Feffer 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | 33.9 (9.8) | 100 | N | Y | N | N | N | |

| Riegler 2023 | Non-randomised experimental study | 34.3 (10.05) | 73.2 | N | N | Y | N | N | 8 weeks |

| Assmann 2025 | Randomised controlled trial | 29 | 90 | N | N | N | Y | N | 12 months |

| Schindler 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | 31.7 (10.2) | 78 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 months |

| Mohammadsadeghi 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | 26.85 (8.63) | 45 | Y | N | N | N | N | 8 weeks |

| Salamin 2021 | Cohort study | 34.5 (10.4) | 85.5 | N | N | Y | N | N | 2 years (repeated one-year programme) |

| Juul 2022 | Case report | 28 | 100 | N | N | Y | N | N | 20 weeks |

| Wollmer 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | 30.44 (5.80) | 100 | N | N | N | N | Botulinum toxin A | Single treatment at baseline; follow-up assessments to 16 weeks |

| Crawford 2022 | Randomised controlled trial | 28 (7.54) | 73 | Y | N | N | N | N | Up to 6 months of treatment (follow-up period) |

| Lisoni 2020 | 38 (10.9) | 53.3 | N | Y | N | N | N | 3 weeks (15 sessions) | |

| Hafkemeijer 2023 | Case report | Non reported | 100 | N | N | N | N | N | 4 days |

| Grant 2020 | Case report | 42 | 0 | Y | N | N | N | N | 7 months |

| Francis 2024 | Case series | 30.3 | 100 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 weeks |

| Hood 2024 | Randomised controlled trial | N | N | Y | N | N | 18 weeks (18 sessions) | ||

| Sauer-Zavala 2023 | Randomised controlled trial | 33.71 (13.96) | 84 | N | N | Y | N | N | 18 sessions (within 7-month window) |

| Soler 2022 | Qualitative research | 40.3 (6.1) | 95 | N | N | Y | N | N | 12 weeks |

| Other: Non-concurrent multiple baseline single-subject design | 30.6 (12.4) | 83 | N | N | Y | N | N | 8 weeks of EMDR within 15-week study period | |

| Vonderlin 2025 | Cohort study | 31.1 (10.6) | 76.9 | N | N | N | Y | N | 12 months |

| Bartsch 2024 | Non-randomised experimental study | N | N | Y | N | N | 10 to 12 weeks | ||

| Outcome | Global Level of Interest | |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Suicide | ●High (ideas/suicidal behaviours, not suicide itself) |

| Physical | ●Very low | |

| Symptoms | BPD | ●Main target of current clinical research |

| Comorbidities | ●Some comorbidities such as substance and PTSD | |

| Psychosocial functioning | ●Low interest (generally as a secondary outcome) | |

| Societal aspects | ●Very low | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cailhol, L.; St-Amour, S.; Désilets, M.; Larivière, N.; Mills, J.; Klein, R. Reinforcing Gaps? A Rapid Review of Innovation in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Treatment. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080827

Cailhol L, St-Amour S, Désilets M, Larivière N, Mills J, Klein R. Reinforcing Gaps? A Rapid Review of Innovation in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Treatment. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(8):827. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080827

Chicago/Turabian StyleCailhol, Lionel, Samuel St-Amour, Marie Désilets, Nadine Larivière, Jillian Mills, and Rémy Klein. 2025. "Reinforcing Gaps? A Rapid Review of Innovation in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Treatment" Brain Sciences 15, no. 8: 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080827

APA StyleCailhol, L., St-Amour, S., Désilets, M., Larivière, N., Mills, J., & Klein, R. (2025). Reinforcing Gaps? A Rapid Review of Innovation in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Treatment. Brain Sciences, 15(8), 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080827