Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Rehabilitation Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.2. Patients and Programs

- Inpatient or outpatient or home- or community-based;

- Had at least one study group that underwent TT, either with or without adjunctive treatments (e.g., rhythmic auditory stimulation (RAS), weight-bearing support systems, belts, etc.);

- Had at least one study group that underwent another type of gait and walking rehabilitation, such as conventional or robotic gait training.

- Robot-assisted rehabilitation, performed with any robotic walking aid device;

- Conventional rehabilitation, defined as any rehabilitation treatment that included gait and walking exercises, including dance, that did not require any of the above technologies. RAS delivered via headphones during walking was considered equivalent to treatments in which the RAS was delivered verbally by the physiotherapist and was therefore included with conventional treatments.

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Interventions

4.1. Control Groups

4.2. Outcomes

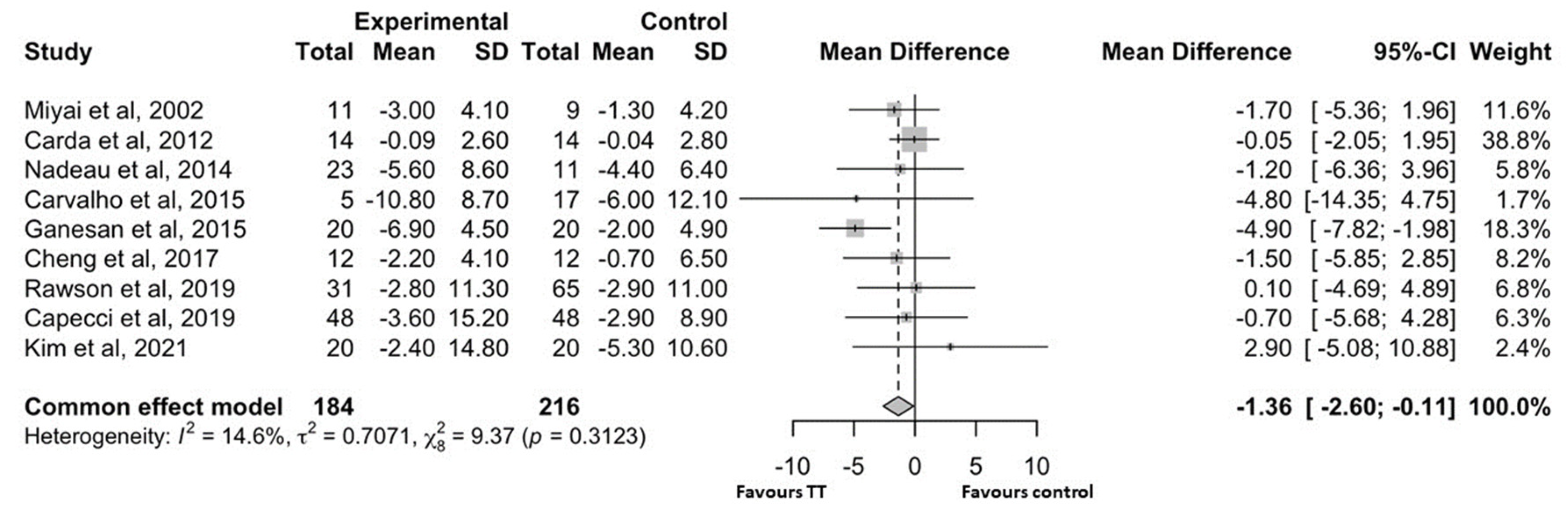

4.2.1. Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

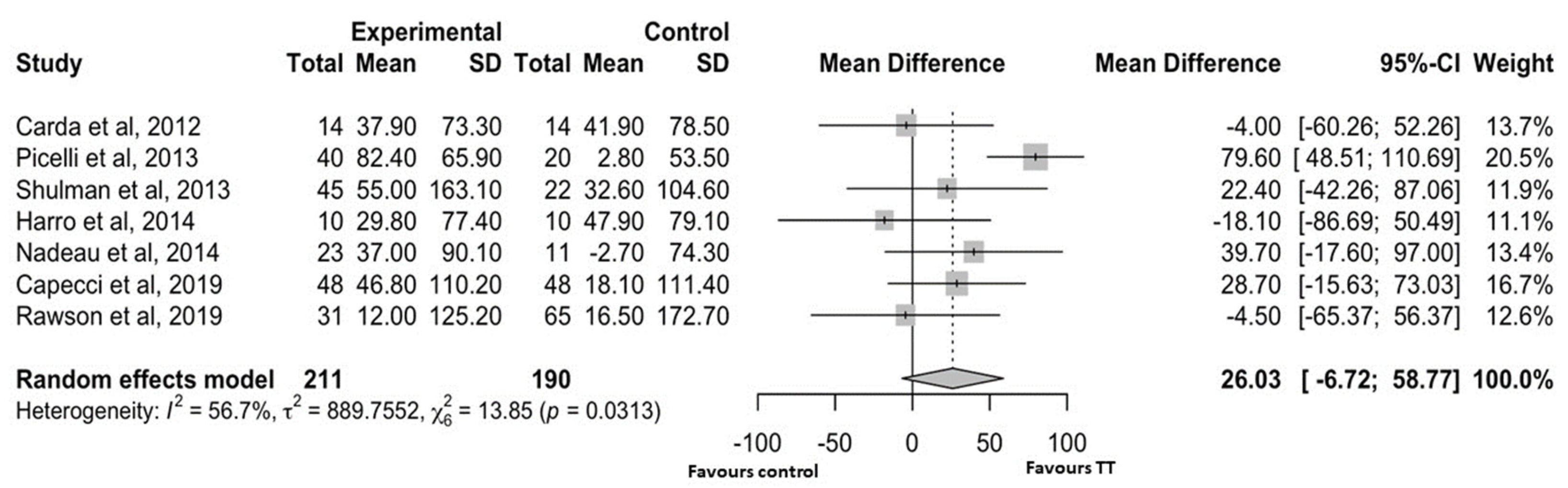

4.2.2. Walking Capacity

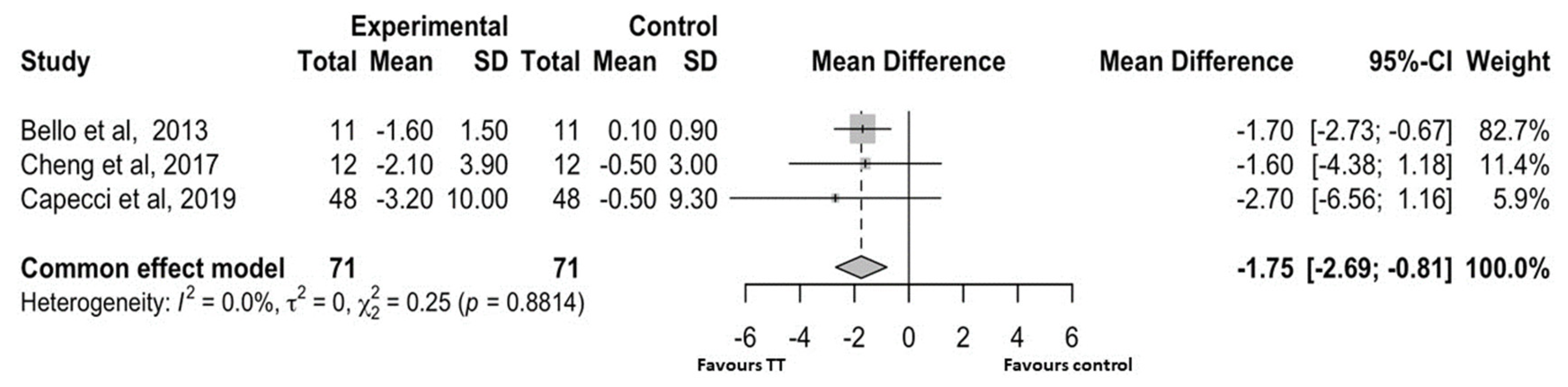

4.2.3. Functional Mobility

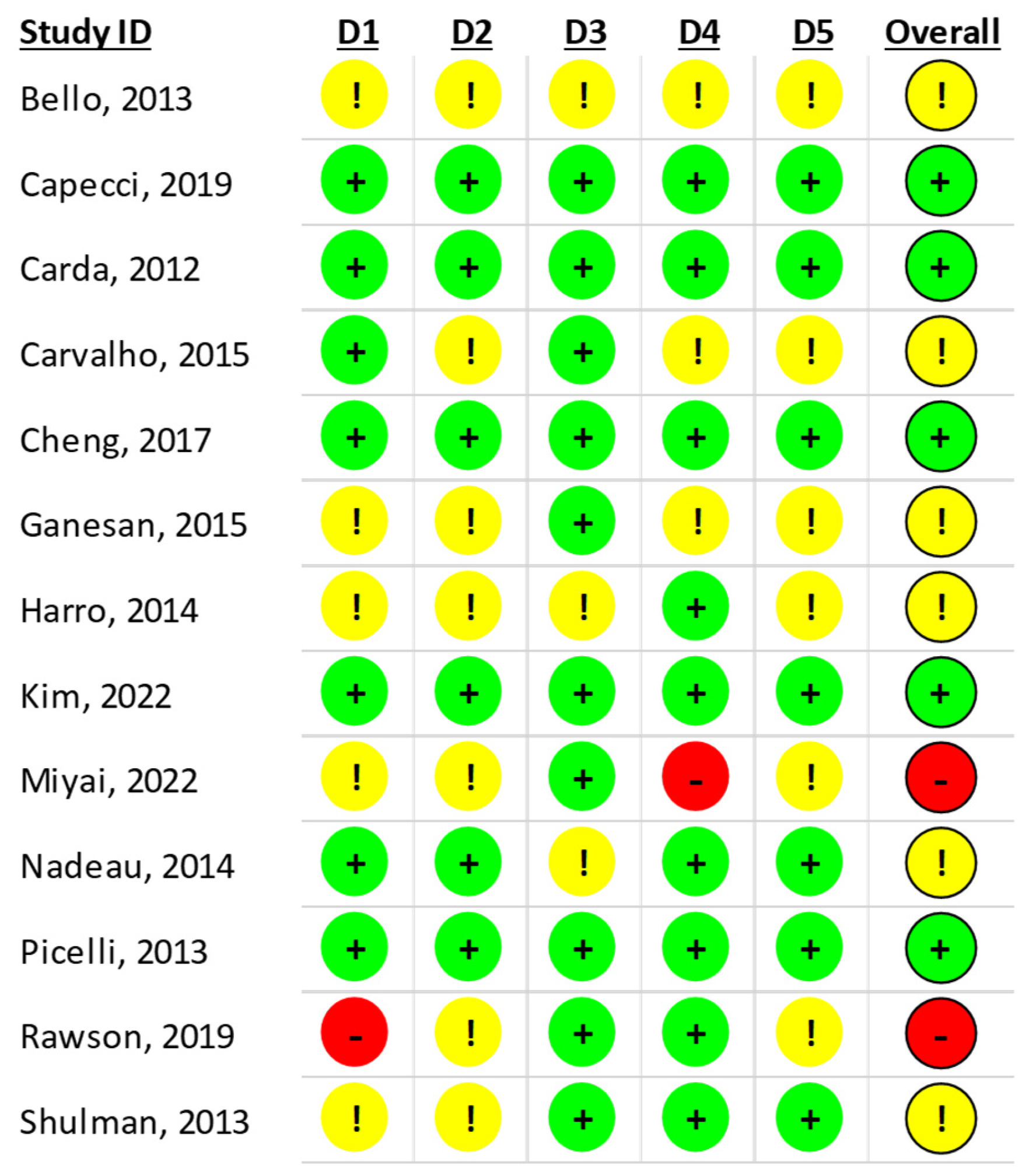

4.2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tolosa, E.; Wenning, G.; Poewe, W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, A.; Schwarzschild, M.A. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: Risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svehlík, M.; Zwick, E.B.; Steinwender, G.; Linhart, W.E.; Schwingenschuh, P.; Katschnig, P.; Ott, E.; Enzinger, C. Gait analysis in patients with Parkinson’s disease off dopaminergic therapy. Arch Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 1880–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, O.; Ferrandez, A.M.; Serratrice, G. Quantitative analysis of gait in Parkinson patients: Increased variability of stride length. J. Neurol. Sci. 1990, 98, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.E.; Iansek, R.; Matyas, T.A.; Summers, J.J. The pathogenesis of gait hypokinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 1994, 117, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, N.M.S.; Brech, G.C.; Canonica, A.; Ernandes, R.C.; Bocalini, D.S.; Greve, J.M.D.; Alonso, A.C. Effects of treadmill training on gait of elders with Parkinson’s disease: A literature review. Einstein 2020, 18, eRW5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radder, D.L.M.; Lígia Silva de Lima, A.; Domingos, J.; Keus, S.H.J.; van Nimwegen, M.; Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M. Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Present Treatment Modalities. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Folkerts, A.K.; Gollan, R.; Lieker, E.; Caro-Valenzuela, J.; Adams, A.; Cryns, N.; Monsef, I.; Dresen, A.; Roheger, M.; et al. Physical exercise for people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD013856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrholz, J.; Kugler, J.; Storch, A.; Pohl, M.; Elsner, B.; Hirsch, K. Treadmill training for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Adler, C.H.; Bloem, B.R.; Chan, P.; Deuschl, G.; Gasser, T.; Goetz, C.G.; Halliday, G.; Joseph, L.; et al. The new definition and diagnostic criteria of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, J.; Keus, S.H.J.; Dean, J.; de Vries, N.M.; Ferreira, J.J.; Bloem, B.R. The European Physiotherapy Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease: Implications for Neurologists. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): Status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2003, 18, 738–750. [CrossRef]

- ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Skorvanek, M.; Rojo-Abuin, J.M.; Gregova, Z.; Stebbins, G.T.; Goetz, C.G.; members of the QUALPD Study Group. Validation study of the Hoehn and Yahr scale included in the MDS-UPDRS. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 651–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015; Available online: http://www.R-project.org.

- Cochrane, W.G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 1954, 10, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, M. Statistica Medica, 2nd ed.; Apogeo Education: Denver, CO, USA, 2019; p. 658. [Google Scholar]

- Der Simonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, K.; Aschermann, Z.; Ács, P.; Deli, G.; Janszky, J.; Komoly, S.; Balázs, É.; Takács, K.; Karádi, K.; Kovács, N. Minimal clinically important difference on the Motor Examination part of MDS-UPDRS. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Crouch, R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.L.; Hsieh, C.L.; Wu, R.M.; Tai, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Lu, W.S. Minimal detectable change of the timed ”up & go” test and the dynamic gait index in people with Parkinson disease. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 114–121, Erratum in: Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Sathyaprabha, T.N.; Pal, P.K.; Gupta, A. Partial Body Weight-Supported Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson Disease: Impact on Gait and Clinical Manifestation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Barbirato, D.; Araujo, N.; Martins, J.V.; Cavalcanti, J.L.; Santos, T.M.; Coutinho, E.S.; Laks, J.; Deslandes, A.C. Comparison of strength training, aerobic training, and additional physical therapy as supplementary treatments for Parkinson’s disease: Pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harro, C.C.; Shoemaker, M.J.; Frey, O.J.; Gamble, A.C.; Harring, K.B.; Karl, K.L.; McDonald, J.D.; Murray, C.J.; Tomassi, E.M.; Van Dyke, J.M.; et al. The effects of speed-dependent treadmill training and rhythmic auditory-cued overground walking on gait function and fall risk in individuals with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2014, 34, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.M.; Katzel, L.I.; Ivey, F.M.; Sorkin, J.D.; Favors, K.; Anderson, K.E.; Smith, B.A.; Reich, S.G.; Weiner, W.J.; Macko, R.F. Randomized clinical trial of 3 types of physical exercise for patients with Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013, 70, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Wu, Y.R.; Cheng, S.J.; Wang, R.Y. Effects of curved-walking training on curved-walking performance and freezing of gait in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 43, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeau, A.; Pourcher, E.; Corbeil, P. Effects of 24 wk of treadmill training on gait performance in Parkinson’s disease. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picelli, A.; Melotti, C.; Origano, F.; Neri, R.; Waldner, A.; Smania, N. Robot-assisted gait training versus equal intensity treadmill training in patients with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Park. Relat. Disord. 2013, 19, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecci, M.; Pournajaf, S.; Galafate, D.; Sale, P.; Le Pera, D.; Goffredo, M.; De Pandis, M.F.; Andrenelli, E.; Pennacchioni, M.; Ceravolo, M.G.; et al. Clinical effects of robot-assisted gait training and treadmill training for Parkinson’s disease. A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, K.S.; McNeely, M.E.; Duncan, R.P.; Pickett, K.A.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Earhart, G.M. Exercise and Parkinson Disease: Comparing Tango, Treadmill, and Stretching. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2019, 43, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O.; Sanchez, J.A.; Lopez-Alonso, V.; Márquez, G.; Morenilla, L.; Castro, X.; Giraldez, M.; Santos-García, D.; Fernandez-del-Olmo, M. The effects of treadmill or overground walking training programme on gait in Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 2013, 38, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carda, S.; Invernizzi, M.; Baricich, A.; Comi, C.; Croquelois, A.; Cisari, C. Robotic gait training is not superior to conventional treadmill training in parkinson disease: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2012, 26, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, E.; Yun, S.J.; Kang, M.G.; Shin, H.I.; Oh, B.M.; Seo, H.G. Robot-assisted gait training with auditory and visual cues in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyai, I.; Fujimoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Ueda, Y.; Saito, T.; Nozaki, S.; Kang, J. Long-term effect of body weight-supported treadmill training in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1370–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.E. Movement disorders in people with Parkinson disease: A model for physical therapy. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muslimovic, D.; Post, B.; Speelman, J.D.; Schmand, B.; de Haan, R.J.; CARPA Study Group. Determinants of disability and quality of life in mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2008, 70, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcan, K.; Guclu-Gunduz, A.; Yasar, E.; Sucullu Karadag, Y.; Saygili, F. The effects of augmented and virtual reality gait training on balance and gait in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2023, 123, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, D.G.; Benninger, D.H. Physical Therapy for Freezing of Gait and Gait Impairments in Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G.; Masud, T.; Kendrick, D.; Morris, R.; Gawler, S.; Treml, J.; Iliffe, S. Does the timed up and go test predict future falls among British community-dwelling older people? Prospective cohort study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, L.; Canning, C.G.; Song, J.; Clemson, L.; Allen, N.E. The effect of rehabilitation interventions on freezing of gait in people with Parkinson’s disease is unclear: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 3199–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitacca, M.; Olivares, A.; Comini, L.; Vezzadini, G.; Langella, A.; Luisa, A.; Petrolati, A.; Frigo, G.; Paneroni, M. Exercise Intolerance and Oxygen Desaturation in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Triggers for Respiratory Rehabilitation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, L.M.; de Araujo, O.F.M.; Barbosa Roca, R.S.; Pimentel, A.D.S.; Neves, L.M.T.; Crisp, A.H.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Correale, L.; Coertjens, M.; Passos-Monteiro, E. Can walking capacity predict respiratory functions of people with Parkinson’s disease? Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1531571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.F.; Binda, K.H.; Real, C.C. The effects of treadmill exercise in animal models of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 1056–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | No. of Studies (No. of Participants) | Pre-Intervention Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 13 (565) | 65.41 ± 3.62 |

| Male, n (%) | 12 (531) | 315 (59.3%) |

| Height, cm | 7 (274) | 165.43 ± 4.65 |

| Weight, kg | 6 (252) | 68.11 ± 8.9 |

| Duration of the disease, years | 12 (531) | 5.96 ± 1.72 |

| Mini Mental State Examination score | 8 (389) | 27.32 ± 1.22 |

| Hoehn and Yahr scale score | 13 (565) | 2.35 ± 0.42 |

| UPDRS-III score | 11 (517) | 26.88 ± 7.65 |

| Ref. | H&Y Inclusion | H&Y Score, Mean ± SD | UPDRS- III Score | Disease Duration, Years | Program Duration, Weeks | Dropouts, n | Participants, n | Intervention and Control | Intensity of TT | Frequency of TT | Duration of TT | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ganesan 2015 [24] | Stage ≤ 3 | 2.08 ± 0.18 | 30.93 ± 1.48 | 5.4 ± 1.56 | 4 | 0 | 20 20 | Intervention: Partial weight-supported treadmill with unweighting support system (±20%) and visual monitoring of step length Control: Conventional gait training with verbal cues and swinging strategies + non-intervention group ± excluded | 3 sets of 10 min training interspersed with 2 min of rest, at comfortable speed initially, with progressive increase to fast comfortable speed | 4 times/week | 5 min warm up + 30 min training + 5 min cool down | Outpatient |

| Carvalho 2015 [25] | Stages 1–3 | 2.3 ± 0.35 | 36.01 ± 6.32 | 5.63 ± 1.49 | 12 | 0 | 5 8 9 | Intervention: Treadmill training Control: (A) Strength exercises for large muscle groups (B) Calisthenics exercises and gait training | 60% of estimated VO2 max or 70% of predicted HR max | 2 times/week | 5 min warm up + 30 min training + 5 min cool down | Outpatient |

| Harro 2014 [26] | Stages 1–3 | 1.93 ± 0.57 | 4.12 ± 2.26 | 6 | 1 1 | 10 10 | Intervention: Speed-dependent treadmill training Control: RAS during ground walking using headphones with a personalized music playlist at bpm based on comfortable gait speed, which was progressively increased | Three 5 min intervals: 1st and 2nd at maximal walking speed, 3rd at 5% more than maximal walking speed, interspersed with 2.5 min at comfortable gait speed | 3 times/week | 5 min warm up + 20 min training + 5 min cool down | Unknown | |

| Shulman 2013 [27] | Stages 1–3 | 2.18 ± 0.36 | 32.1 ± 9.9 | 6.2 ± 3.8 | 12 | 3 4 5 | 23 22 22 | Intervention: (A) High-intensity treadmill (B) Low-intensity treadmill Control: Stretching and lower limbs resistance training | Initially 15 min at 40–50% of the maximal HRR, increased by 0.2 km/h every 5 min (increased by 1% every 2 weeks) until 30 min (70–80% of HRR). Initially 15 min at 0% incline and self-selected pace, increased by 5 min to reach 50 min | 3 times/week | 30 min high-intensity training, 50 min low-intensity training | Community-based? |

| Cheng 2017 [28] | Stages 1–3 | 1.9 ± 0.47 | 19.6 ± 2.19 | 7.1 ± 1.78 | 4–6 | 0 | 12 12 | Intervention: Turning-based curved treadmill Control: Trunk and upper limb exercises + both groups also performed 10 min of overground gait training | 15 min clockwise and 15 min counterclockwise at 80% of comfortable walking speed initially, progressively increased by 0.05 m/s every 5 min as tolerated | 2 or 3 times/week | 30 min | Unknown |

| Nadeau 2014 [29] | Stage ≤ 2 | 1.91 ± 0.25 | 23.15 ± 4.28 | 24 | 17 18 23 | 12 11 11 | Intervention: (A) Speed treadmill (B) Mixed treadmill Control: Low-intensity exercise routine ± tai chi, dance, coordination, and resistance band exercises | 80% of preferential walking speed, progressing to 90–100% with speed increased by 0.2 km/h each session 80% of preferential walking speed, progressing to 90–100% with alternating increase in speed of 0.2 km/h or in incline of 1% each session | 3 times/week | 5 min warm up + 45 min training + 5 min cool down | Outpatient | |

| Picelli 2013 [30] | 3 | 3 | 18.02 ± 1.53 | 6.77 ± 5.8 | 4 | 0 | 20 20 20 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: (A) RAGT with GT1 and partial body weight support (B) Conventional gait training with proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation | 3 sets of 10 min at speeds of 1, 1.5, and 2 km/h, respectively, interspersed with 5 min of rest | 3 times/week | 45 min | Outpatient |

| Capecci 2019 [31] | Stage ≥ 2 | 3 ± 0.74 | 23.65 ± 2.77 | 8.9 ± 4.8 | 4 | 2 12 | 48 48 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: RAGT with G-EO and partial body weight support at increasing speed | Initial speed of 0.8–1 km/h, gradually increasing to 2.0 km/h or higher depending on tolerance | 5 times/week | 45 min | Outpatient |

| Rawson 2019 [32] | Stages 1–4 | 2.18 ± 0.52 | 36.69 ± 11.19 | 5.47 ± 4.59 | 12 | 12 7 12 | 29 36 23 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: (A) Argentine tango with a caregiver (B) Stretching and flexibility whole-body exercises | Preferred walking speed | 2 times/week | 60 min with minimal warm up and cool down | Community-based |

| Bello 2013 [33] | Stages 1–4 | 2.16 ± 0.20 | 20.36 ± 3.73 | 4.89 ± 1.26 | 5 | Unknown | 11 11 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: Overground training with RAS | 4 bouts of 4 min of walking at preferred speed, interspersed with 3 min of rest, increasing by 4 min every week | 3 times/week | 25 min initially, increasing to 40 min | Unknown |

| Carda 2012 [34] | Stage < 3 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 10.53 ± 4.04 | 3.73 ± 0.25 | 4 | 1 1 | 14 14 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: RAGT with Lokomat and partial body weight support | Initial speed at 80% of the mean speed of the 6 MWT, progressively increasing to 100% in the last two weeks of training | 3 times/week | 30 min | Outpatient |

| Kim 2022 [35] | Stages 2.5–3 | 2.8 ± 0.24 | 36.6 ± 3.58 | 9 ± 1.56 | 4 | 2 2 | 20 20 | Intervention: Treadmill Control: RAGT with Walkbot-S and visual feedback and auditory cues at the toe-off phase to improve the rhythm of the gait + contemporary rehabilitation treatments allowed in both groups | Initial speed based on subjects’ height and gradually increasing throughout the sessions to the maximal velocity, depending on tolerance | 3 times/week | 15 min warm up and cool down + 30 min training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boccali, E.; Simonelli, C.; Salvi, B.; Paneroni, M.; Vitacca, M.; Di Pietro, D.A. Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Rehabilitation Outcomes. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080788

Boccali E, Simonelli C, Salvi B, Paneroni M, Vitacca M, Di Pietro DA. Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Rehabilitation Outcomes. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(8):788. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080788

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoccali, Elisa, Carla Simonelli, Beatrice Salvi, Mara Paneroni, Michele Vitacca, and Davide Antonio Di Pietro. 2025. "Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Rehabilitation Outcomes" Brain Sciences 15, no. 8: 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080788

APA StyleBoccali, E., Simonelli, C., Salvi, B., Paneroni, M., Vitacca, M., & Di Pietro, D. A. (2025). Treadmill Training in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Rehabilitation Outcomes. Brain Sciences, 15(8), 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080788