Anxious Traits Intensify the Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Stigma in People Living with HIV

Abstract

1. Introduction

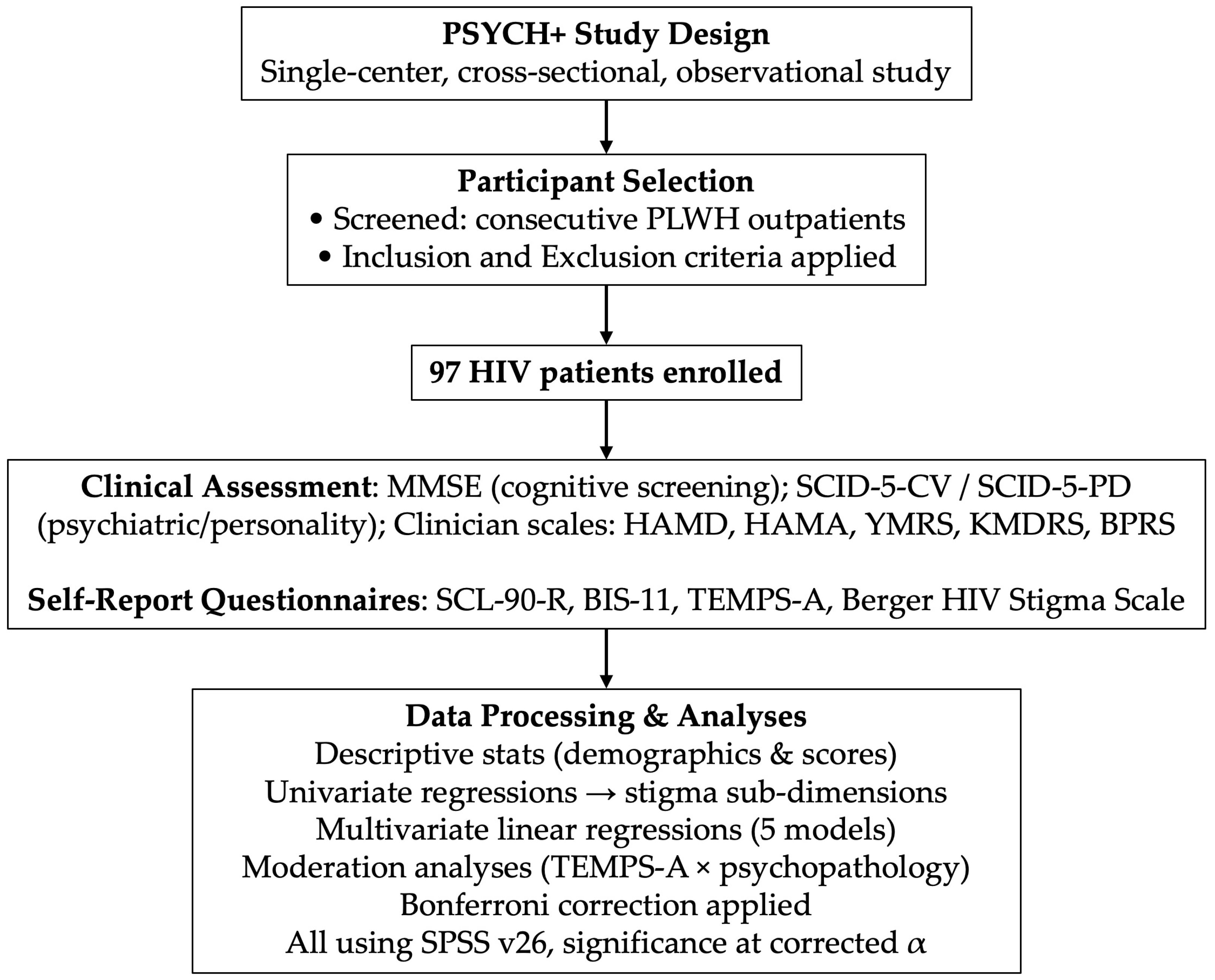

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Regression Analysis

3.2.1. Univariate Regression Analysis

3.2.2. Multivariate Regression Analysis

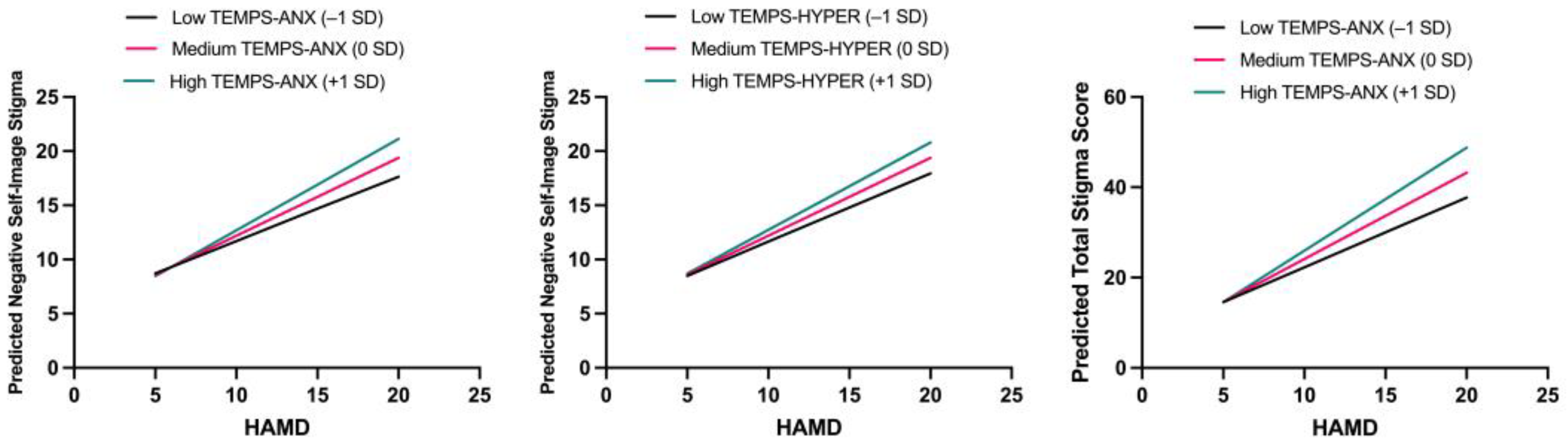

3.2.3. Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIS-11 | Barratt Impulsiveness Scale |

| BPRS | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale |

| HAMA | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale |

| HAMD | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| KMDRS | Koukopoulos Mixed Depression Rating Scale |

| MLR | Multivariate linear regression |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| SCID-5-CV | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, Clinical Version |

| SCID-5-PD | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, Personality Disorders |

| SCL-90-R | Symptom Checklist-90 Revised |

| TEMPS-A | Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego |

| YMRS | Young Mania Rating Scale |

References

- Govender, R.D.; Hashim, M.J.; Khan, M.A.; Mustafa, H.; Khan, G. Global Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS: A Resurgence in North America and Europe. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzeszutek, M.; Gruszczyńska, E.; Pięta, M.; Malinowska, P. HIV/AIDS Stigma and Psychological Well-Being After 40 Years of HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1990527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, E. Stigma Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Touchstone: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Rintamaki, L.S.; Davis, T.C.; Skripkauskas, S.; Bennett, C.L.; Wolf, M.S. Social Stigma Concerns and HIV Medication Adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2006, 20, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera-Mijares, S.; Martínez-Dávalos, A.; Vermandere, H.; Bautista-Arredondo, S. HIV Care Disengagement and Antiretroviral Treatment Discontinuation in Mexico: A Qualitative Study Based on the Ecological Model Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C.S.; Coleman, R. Aids-Related Stigmatization and the Disruption of Social Relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1992, 9, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, A.W.; Rubin, L.H.; Paul, R.H. The Interaction of HIV with Mental Health in the Modern Antiretroviral Therapy Era. Psychosom. Med. 2022, 84, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, A.; Lijffijt, M.; Kahlon, R.S.; Gandy, K.; Arvind, R.P.; Amin, P.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Swann, A.C.; Soares, J.C.; Saxena, K. Early and Late Cortical Reactivity to Passively Viewed Emotional Faces in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcovych, M.T.; Manning, A.A.; Semenova, S.; Gamaldo, C.; Haughey, N.J.; Slusher, B.S. The Psychiatric Impact of HIV. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 1432–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Rahmati, J.; Hosseinifard, H.; Dehnad, A.; Aryankhesal, A.; Shabaninejad, H.; Ghasemyani, S.; Alihosseini, S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; et al. Global Prevalence of Depression in HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 9, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jia, L.; Cai, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T.; Guo, C. People Who Living with HIV/AIDS Also Have a High Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1259290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartzler, B.; Dombrowski, J.C.; Crane, H.M.; Eron, J.J.; Geng, E.H.; Christopher Mathews, W.; Mayer, K.H.; Moore, R.D.; Mugavero, M.J.; Napravnik, S.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Substance Use Disorders Among HIV Care Enrollees in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Goldsamt, L.; Meng, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Williams, A.B.; Wang, H. Global Estimate of the Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Adults Living with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, L.R.; Bailey, L.; Jessani, A.; Postnikoff, J.; Kerston, P.; Brondani, M. Stigma Experiences in Marginalized People Living with HIV Seeking Health Services and Resources in Canada. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2016, 27, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.-Y.; Beymer, M.R.; Suen, S. Chronic Disease Onset Among People Living with HIV and AIDS in a Large Private Insurance Claims Dataset. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, M.A.; Collins, R.; Cunningham, W.E.; Morton, S.C.; Zierler, S.; Wong, M.; Tu, W.; Kanouse, D.E. Perceived Discrimination in Clinical Care in a Nationally Representative Sample of HIV-Infected Adults Receiving Health Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.A.A.; Artz, J.; Azeb Shahul, H.; Gonsolin, C.; Shah, R.; Dacarett-Galeano, D.; Pereira, L.F.; Cozza, K.L. The Definition and Scope of HIV Psychiatry: How to Provide Compassionate Care. In HIV Psychiatry; Bourgeois, J.A., Cohen, M.A.A., Makurumidze, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-3-030-80664-4. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola, M.; Pepe, M.; Montanari, S.; Spera, M.C.; Panaccione, I.; Simonetti, A.; Sani, G. Vortioxetine Improves Physical and Cognitive Symptoms in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Major Depressive Episodes. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023, 70, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horberg, M.; Thompson, M.; Agwu, A.; Colasanti, J.; Haddad, M.; Jain, M.; McComsey, G.; Radix, A.; Rakhmanina, N.; Short, W.R.; et al. Primary Care Guidance for Providers Who Care for Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2024 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, S.; Mitra, S.; Chen, S.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Chambers, L.; Wilson, M.; Logie, C.H.; Shi, Q.; Morassaei, S.; et al. Examining the Associations Between HIV-Related Stigma and Health Outcomes in People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Series of Meta-Analyses. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, J.R.; Wetherall, K. The Association between HIV-Stigma and Depressive Symptoms among People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review of Studies Conducted in South Africa. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Djenderedjian, A.M.; Rosenthal, R.H.; Khani, M.K. Cyclothymic Disorder: Validating Criteria for Inclusion in the Bipolar Affective Group. AJP 1977, 134, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Akiskal, K.; Allilaire, J.-F.; Azorin, J.-M.; Bourgeois, M.L.; Sechter, D.; Fraud, J.-P.; Chatenêt-Duchêne, L.; Lancrenon, S.; Perugi, G.; et al. Validating Affective Temperaments in Their Subaffective and Socially Positive Attributes: Psychometric, Clinical and Familial Data from a French National Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Akiskal, K.K.; Haykal, R.F.; Manning, J.S.; Connor, P.D. TEMPS-A: Progress towards Validation of a Self-Rated Clinical Version of the Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Autoquestionnaire. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihmer, Z.; Akiskal, K.K.; Rihmer, A.; Akiskal, H.S. Current Research on Affective Temperaments. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.E.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 Years of Clinical Experience and Scientific Insight on Affective Temperaments in Psychiatric Disorders: State of the Art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, A.; Luciano, M.; Sampogna, G.; Rocca, B.D.; Mancuso, E.; De Fazio, P.; Di Nicola, M.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Pepe, M.; Sambataro, F.; et al. Effect of Affective Temperament on Illness Characteristics of Subjects with Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 334, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, C.; Bruno, A.; Turiaco, F.; Imbesi, M.; Arena, F.; Capillo, A.; Pandolfo, G.; Silvestri, M.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Mento, C. The Predictivity Role of Affective Temperaments in Mood Alteration. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 17, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, E.G.; Saab, D.; Jabbour, S.; Karam, G.E.; Hantouche, E.; Angst, J. The Role of Affective Temperaments in Bipolar Disorder: The Solid Role of the Cyclothymic, the Contentious Role of the Hyperthymic, and the Neglected Role of the Irritable Temperaments. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, K.K.; Kugathasan, P.; Straarup, K.N. Characteristics, Correlates and Outcomes of Perceived Stigmatization in Bipolar Disorder Patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 194, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmi, L.; Amamou, B.; Ben Haouala, A.; Mhalla, A.; Gaha, L. Attitudes Toward Mental Illness among Medical Students and Impact of Temperament. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, C.; Kameyama, R.; Toda, H.; Masuya, J.; Ichiki, M.; Kusumi, I.; Inoue, T. Utility of TEMPS-A in Differentiation Between Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar I Disorder, and Bipolar II Disorder. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miola, A.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Pinna, M.; Tondo, L. Relationships of Affective Temperament Ratings to Diagnosis and Morbidity Measures in Major Affective Disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göpfert, N.C.; Conrad von Heydendorff, S.; Dreßing, H.; Bailer, J. Applying Corrigan’s Progressive Model of Self-Stigma to People with Depression. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, L.T.; Brown, C.H.; Lucksted, A.; Hack, S.M.; Drapalski, A.L. Support for the Social-Cognitive Model of Internalized Stigma in Serious Mental Illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 137, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb, B.E.; Coles, M.E. Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Models of Psychopathology: A Developmental Perspective. In Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 104–135. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, S.M.; Cummins, L.F. Diathesis-Stress Models. In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-470-67127-6. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Benjamin, L.S.; Spitzer, R.L. User’s Guide for the SCID-5-PD (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorder); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. Development of a Rating Scale for Primary Depressive Illness. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1967, 6, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. The Assessment of Anxiety States by Rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1959, 32, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A Rating Scale for Mania: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, G.; Vöhringer, P.A.; Barroilhet, S.A.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Ghaemi, S.N. The Koukopoulos Mixed Depression Rating Scale (KMDRS): An International Mood Network (IMN) Validation Study of a New Mixed Mood Rating Scale. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, J.E.; Gorham, D.R. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): Recent Developments in Ascertainment and Scaling. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-Mental State. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Unger, R. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-470-17024-3. [Google Scholar]

- Reise, S.P.; Moore, T.M.; Sabb, F.W.; Brown, A.K.; London, E.D. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale–11: Reassessment of Its Structure in a Community Sample. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, B.E.; Ferrans, C.E.; Lashley, F.R. Measuring Stigma in People with HIV: Psychometric Assessment of the HIV Stigma Scale. Res. Nurs. Health 2001, 24, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, F.; Zenbaba, D.; Sahiledengle, B.; Tekalegn, Y.; Woldeyohannes, D.; Atlaw, D.; Nugusu, F.; Baffa, L.D.; Gomora, D.; Beressa, G. Perceived Stigma and Depression Among the HIV-Positive Adult People in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.F.; Tam, C.C.; Yang, X.; Qiao, S.; Li, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, Y. Associations Between Internalized and Anticipated HIV Stigma and Depression Symptoms Among People Living with HIV in China: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Model. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 4052–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.F.; Zhang, R.; Qiao, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Z. Longitudinal Analysis of the Relationship Between Internalized HIV Stigma, Perceived Social Support, Resilience, and Depressive Symptoms Among People Living with HIV in China: A Four-Wave Model. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahn, R.; Lythe, K.E.; Gethin, J.A.; Green, S.; Deakin, J.F.W.; Young, A.H.; Moll, J. The Role of Self-Blame and Worthlessness in the Psychopathology of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 186, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrios, G.E.; Bulbena, A.; Bakshi, N.; Dening, T.R.; Jenaway, A.; Markar, H.; Martin-Santos, R.; Mitchell, S.L. Feelings of Guilt in Major Depression: Conceptual and Psychometric Aspects. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 160, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, P.; Lawrence, A.J.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Xie, G.; Yang, X.; Zahn, R. The Psychopathology of Worthlessness in Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 818542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, L.; Yao, X.; Lin, J.; Meng, X. Associations Between Self-Disgust, Depression, and Anxiety: A Three-Level Meta-Analytic Review. Acta Psychol. 2022, 228, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMoult, J.; Gotlib, I.H. Depression: A Cognitive Perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 69, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świtaj, P.; Grygiel, P.; Anczewska, M.; Wciórka, J. Loneliness Mediates the Relationship Between Internalised Stigma and Depression Among Patients with Psychotic Disorders. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, B.A.; Mohatt, N.V.; Prince, D.M.; Thompson, A.B.; Matlin, S.L.; Tebes, J.K. Socio-Psychological Mediators of the Relationship Between Behavioral Health Stigma and Psychiatric Symptoms. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 181, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, C.L.; Wang, K.; Pachankis, J.E. Does Getting Stigma Under the Skin Make It Thinner? Emotion Regulation as a Stress-Contingent Mediator of Stigma and Mental Health. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Keyworth, C.; O’Connor, D.B. Effects of Childhood Trauma on Mental Health Outcomes, Suicide Risk Factors and Stress Appraisals in Adulthood. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, M.; Girardi, P.; Tatarelli, R.; Iliceto, P.; De Pisa, E.; Tondo, L.; Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. TEMPS-A (Rome): Psychometric Validation of Affective Temperaments in Clinically Well Subjects in Mid- and South Italy. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 107, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampman, O.; Viikki, M.; Leinonen, E. Anxiety Disorders and Temperament—An Update Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Edgar, K.; Fox, N.A. Temperament and Anxiety Disorders. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 14, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.03 ± 11.32 |

| Gender, % | 69.1% Male |

| 28.9% Female | |

| 2.1% Transgender | |

| Marital status, % | 49.5% Single |

| 37.1% Married or living with a partner | |

| 9.3% Separated/divorced | |

| 4.1% Widowed | |

| Level of education, % | 1% Elementary school |

| 9.3% Middle school | |

| 57.7% High school | |

| 32.2% University degree | |

| Employment status, % | 23.7% Unemployed |

| 75.3% Employed | |

| Years from diagnosis, mean (SD) | 15.75 ± 9.61 |

| CD4+ levels (cells/mm3), mean (SD) | 633.19 ± 240.05 |

| Years of ART therapy, mean (SD) | 14.24 ± 8.95 |

| Number of ART medications taken, mean (SD) | 2.89 ± 0.81 |

| Past psychiatric disorder, % | 63.5% No |

| 36.5% Yes | |

| Current psychiatric disorder, % | 75.0% No |

| 25.0% Yes | |

| Past psychiatric hospitalization, % | 97.9% No |

| 2.1% Yes | |

| Past suicide attempts, % | 97.9% No |

| 2.1% Yes | |

| Past psychopharmacological treatment, % | 67.7% No |

| 32.3% Yes | |

| Current psychopharmacological treatment, % | 76.0% No |

| 24.0% Yes | |

| Number of psychotropic drugs taken, mean (SD) | 0.34 ± 0.69 |

| Family history of psychiatric disorders, % | 68.0% No |

| 32.0% Yes | |

| Past substance use, % | 71.1% No |

| 28.9% Yes | |

| Current substance use, % | 88.7% No |

| 11.3% Yes | |

| HAMD, mean (SD) | 6.95 ± 5.69 |

| HAMA, mean (SD) | 6.47 ± 5.57 |

| YMRS, mean (SD) | 4.40 ± 4.22 |

| KMDRS, mean (SD) | 8.10 ± 3.99 |

| BPRS, mean (SD) | 28.95 ± 7.71 |

| SCL90-R, mean (SD) | |

| SOM | 0.69 + 0.64 |

| O-C | 0.80 + 0.79 |

| I-S | 0.64 + 0.68 |

| DEP | 0.76 + 0.79 |

| ANX | 0.62 + 0.62 |

| HOS | 0.47 + 0.62 |

| PHOB | 0.21 + 0.38 |

| PAR | 0.69 + 0.69 |

| PSY | 0.52 + 0.61 |

| GSI | 0.64 + 0.59 |

| PST | 32.25 + 21.68 |

| PSDI | 1.52 + 0.49 |

| BIS, mean (SD) | |

| A | 9.45 + 2.21 |

| M | 12.44 + 3.48 |

| SC | 13.17 + 3.16 |

| CC | 12.14 + 2.56 |

| P | 7.48 + 1.94 |

| CI | 5.42 + 1.59 |

| AI | 14.86 + 2.86 |

| MI | 19.92 + 4.39 |

| NPI | 25.30 + 4.86 |

| Total | 60.08 + 9.81 |

| TEMPS, mean (SD) | |

| DYS | 9.74 + 4.48 |

| CYCL | 8.39 + 5.76 |

| HYPER | 10.88 + 3.95 |

| IRR | 7.14 + 6.37 |

| ANX | 10.75 + 7.58 |

| HIV Stigma Scale, mean (SD) | |

| PS | 36.01 + 12.71 |

| DC | 28.22 + 6.27 |

| NSI | 26.30 + 7.77 |

| CwPA | 45.41 + 12.61 |

| Total | 91.05 + 22.83 |

| Predictor Variable | B | S.E. | β | t | p-Value | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Negative self-image | ||||||

| TEMPS-DYS | 0.449 | 0.327 | 0.262 | 1.374 | 0.173 | −0.202–1.100 |

| TEMPS-CYCL | 0.396 | 0.266 | 0.298 | 1.488 | 0.141 | −0.134–0.927 |

| TEMPS-HYPER | −0.338 | 0.195 | −0.172 | −1.731 | 0.087 | −0.726–0.051 |

| TEMPS-IRR | −0.027 | 0.220 | −0.023 | −0.125 | 0.901 | −0.466–0.411 |

| TEMPS-ANX | −0.752 | 0.239 | −0.733 | −3.147 | 0.002 | −1.227–−0.276 |

| HAMD | 0.719 | 0.153 | 0.533 | 4.687 | 0.000 | 0.414–1.024 |

| TEMPS-DYS × HAMD | −0.079 | 0.053 | −0.295 | −1.498 | 0.138 | −0.185–0.026 |

| TEMPS-CYCL × HAMD | −0.027 | 0.043 | −0.114 | −0.638 | 0.525 | −0.113–0.058 |

| TEMPS-HYPER × HAMD * | 0.088 | 0.039 | 0.247 | 2.258 | 0.027 | 0.010–0.166 |

| TEMPS-IRR × HAMD | −0.042 | 0.040 | −0.165 | −1.047 | 0.298 | −0.122–0.038 |

| TEMPS-ANX × HAMD ** | 0.125 | 0.035 | 0.748 | 3.588 | 0.001 | 0.056–0.194 |

| Model 2: Total stigma score | ||||||

| TEMPS-DYS | 0.931 | 0.998 | 0.186 | 0.933 | 0.354 | −1.056–2.919 |

| TEMPS-CYCL | 1.160 | 0.814 | 0.298 | 1.425 | 0.158 | −0.460–2.780 |

| TEMPS-HYPER | −0.766 | 0.596 | −0.133 | −1.286 | 0.202 | −1.953–0.420 |

| TEMPS-IRR | −0.665 | 0.672 | −0.188 | −0.989 | 0.326 | −2.003–0.674 |

| TEMPS-ANX | −1.533 | 0.730 | −0.511 | −2.100 | 0.039 | −2.986–−0.080 |

| HAMD | 1.912 | 0.469 | 0.485 | 4.080 | 0.000 | 0.979–2.845 |

| TEMPS-DYS × HAMD | −0.219 | 0.162 | −0.278 | −1.349 | 0.181 | −0.541–0.104 |

| TEMPS-CYCL × HAMD | −0.080 | 0.131 | −0.113 | −0.607 | 0.546 | −0.341–0.182 |

| TEMPS-HYPER × HAMD | 0.222 | 0.120 | 0.213 | 1.859 | 0.067 | −0.016–0.461 |

| TEMPS-IRR × HAMD | −0.102 | 0.123 | −0.137 | −0.830 | 0.409 | −0.347–0.143 |

| TEMPS-ANX × HAMD ** | 0.336 | 0.106 | 0.687 | 3.156 | 0.002 | 0.124–0.547 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koukopoulos, A.; D’Onofrio, A.M.; Simonetti, A.; Janiri, D.; Cherubini, F.; Vassalini, P.; Santinelli, L.; D’Ettorre, G.; Sani, G.; Camardese, G. Anxious Traits Intensify the Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Stigma in People Living with HIV. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080786

Koukopoulos A, D’Onofrio AM, Simonetti A, Janiri D, Cherubini F, Vassalini P, Santinelli L, D’Ettorre G, Sani G, Camardese G. Anxious Traits Intensify the Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Stigma in People Living with HIV. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(8):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080786

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoukopoulos, Alexia, Antonio Maria D’Onofrio, Alessio Simonetti, Delfina Janiri, Flavio Cherubini, Paolo Vassalini, Letizia Santinelli, Gabriella D’Ettorre, Gabriele Sani, and Giovanni Camardese. 2025. "Anxious Traits Intensify the Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Stigma in People Living with HIV" Brain Sciences 15, no. 8: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080786

APA StyleKoukopoulos, A., D’Onofrio, A. M., Simonetti, A., Janiri, D., Cherubini, F., Vassalini, P., Santinelli, L., D’Ettorre, G., Sani, G., & Camardese, G. (2025). Anxious Traits Intensify the Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Stigma in People Living with HIV. Brain Sciences, 15(8), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080786