Treatment of Insomnia in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

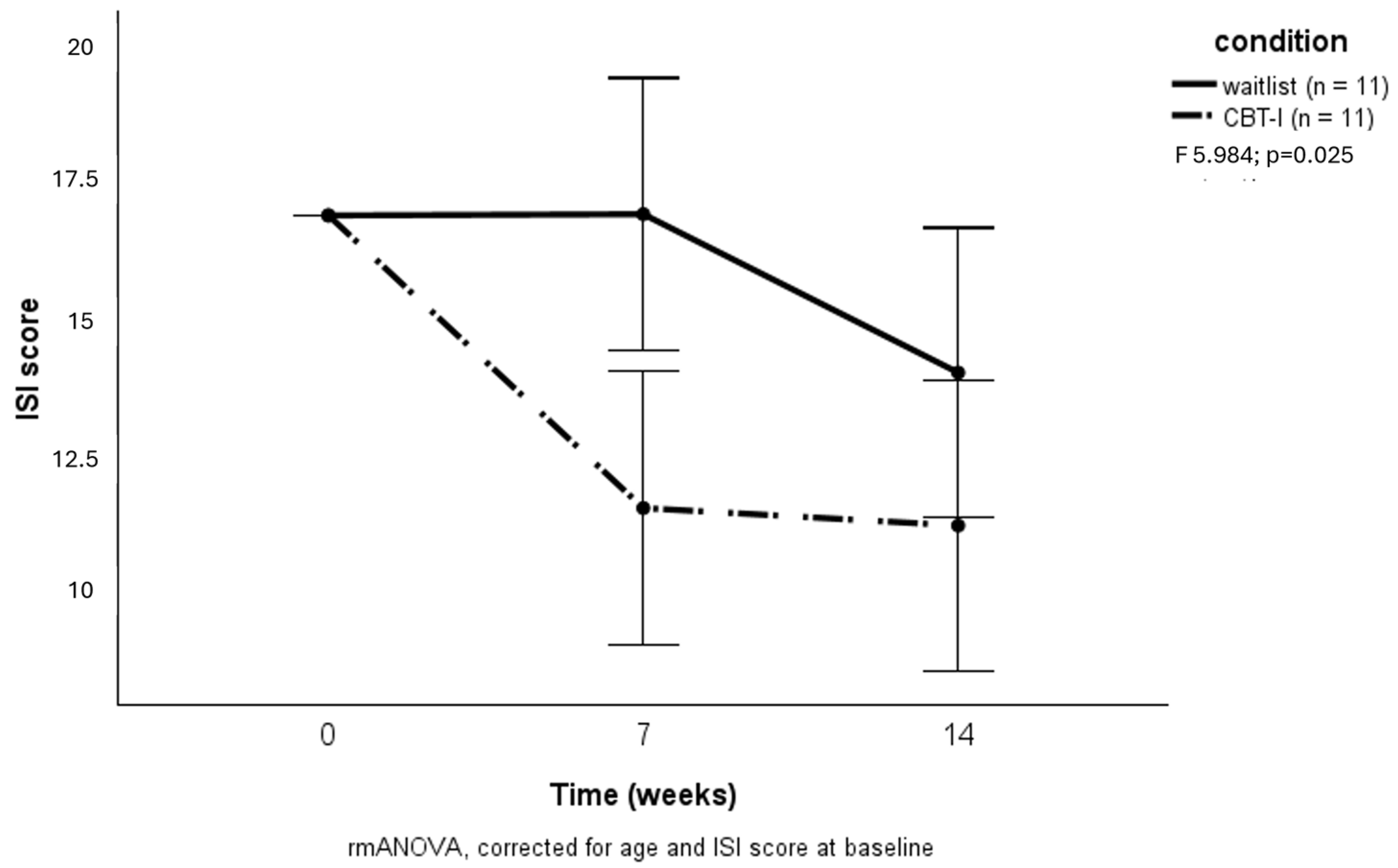

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamphuis, J.; Karsten, J.; de Weerd, A.; Lancel, M. Sleep disturbances in a clinical forensic psychiatric population. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mijnster, T.; Boersma, G.; Engberts, J.; Vreugdenhil-Becherer, L.; Keulen-de Vos, M.; de Vogel, V.; Bulten, E.; Lancel, M. Lying awake in forensic hospitals: A multicenter, cross-sectional study on the prevalence of insomnia and contributing factors in forensic psychiatric patients. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2022, 33, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, M.M.; Karsten, J.; Lancel, M. Poor sleep and its relation to impulsivity in patients with antisocial or borderline personality disorders. Behav. Med. 2017, 43, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglioni, C.; Nanovska, S.; Regen, W.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B.; Nissen, C.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Riemann, D. Sleep and mental disorders: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 969–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Sheaves, B.; Waite, F.; Harvey, A.G.; Harrison, P.J. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.P. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1156, 168–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.A.; Alfano, C.A. Sleep and emotion regulation: An organizing, integrative review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 31, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, J.; Meerlo, P.; Koolhaas, J.M.; Lancel, M. Poor sleep as a potential causal factor in aggression and violence. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z.; Herlache, A.D. Sleep disruption and aggression: Implications for violence and its prevention. Psychol. Violence 2016, 6, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, M.M.; Lancel, M.; Beijer, E.; Remmelzwaal, S.; Rutters, F. The association of sleep quality and aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 12, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, M.M.; Lancel, M.; Şener, O.; Verkes, R.J.; Bouman, E.J.; Rutters, F. Observational and experimental studies on sleep duration and aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 64, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, D.; Baglioni, C.; Bassetti, C.; Bjorvatn, B.; Dolenc Groselj, L.; Ellis, J.G.; Espie, C.A.; Garcia-Borreguero, D.; Gjerstad, M.; Gonçalves, M.; et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 675–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertenstein, E.; Trinca, E.; Wunderlin, M.; Schneider, C.L.; Züst, M.A.; Fehér, K.D.; Su, T.; Straten, A.V.; Berger, T.; Baglioni, C.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with mental disorders and comorbid insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 62, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.M.; Kinnafick, F.; Breen, K.C.; Girardi, A.; Hartescu, I. Behavioural, medical & environmental interventions to improve sleep quality for mental health inpatients in secure settings: A systematic review & meta-analysis. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2022, 33, 745–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijnster, T.; Boersma, G.J.; Meijer, E.; Lancel, M. Effectivity of (personalized) cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in mental health populations and the elderly: An overview. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, M.J.; Snoep, L.; Raniti, M.; Schwartz, O.; Waloszek, J.M.; Simmons, J.G.; Murray, G.; Blake, L.; Landau, E.R.; Dahl, R.E.; et al. A cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based group sleep intervention improves behavior problems in at-risk adolescents by improving perceived sleep quality. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 99, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, P.L.; Bootzin, R.R.; Smith, L.; Cousins, J.; Cameron, M.; Stevens, S. Sleep and aggression in substance-abusing adolescents: Results from an integrative behavioral sleep-treatment pilot program. Sleep 2006, 29, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, F.; Neumann, I.; Yoon, D.; Rettenberger, M.; Stück, E.; Briken, P. Determinants of dropout from correctional offender treatment. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, M.M.; Rutters, F.; Spreen, M.; Lancel, M. Poor sleep quality at baseline is associated with increased aggression over one year in forensic psychiatric patients. Sleep Med. 2020, 67, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M.J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweere, Y.; Kerkhof, G.A.; De Weerd, A.W.; Kamphuisen HA, C.; Kemp, B.; Schimsheimer, R.J. The validity of the dutch sleep disorders questionnaire (sdq). J. Psychosom. Res. 1998, 45, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Projectgroup Risk Assessment in Forensic Psychiatry (Ed.) Manual HKT-30 Version 2002, Risk Assessment in Forensic Psychiatry; Ministerie Van Justitie, Dienst Justitiële Inrichtingen: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2003. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Perlis, M.L.; Jungquist, C.R.; Smith, M.T.; Posner, D.A. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia—A Session-by-Session Guide; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallieres, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Belanger, L.; Ivers, H. The insomnia severity index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Melisaratos, N. The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983, 13, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, J.H.; Stanford, M.S.; Barratt, E.S. Factor structure of the barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 51, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A.G.; Malloy-Diniz, L.; Correa, H. Systematic review of psychometric proprieties of barratt impulsiveness scale version 11 (BIS-11). Clin. Neuropsychiatry J. Treat. Eval. 2012, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morren, M.; Meesters, C. Validation of the dutch version of the aggression questionnaire in adolescent male offenders. Aggress. Behav. 2002, 28, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littner, M.; Kushida, C.A.; Anderson, W.M.; Bailey, D.; Berry, R.B.; Davila, D.G.; Hirshkowitz, M.; Kapen, S.; Kramer, M.; Loube, D.; et al. Practice parameters for the role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms: An update for 2002. Sleep 2003, 26, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, G.D.; Cowan, W.B.; Davis, K.A. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: A model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1984, 10, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M.E.; Sorge, G.B.; Benoit, A.; West, R.F.; Stanovich, K.E. Decision-making and cognitive abilities: A review of associations between iowa gambling task performance, executive functions, and intelligence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Bélanger, L.; LeBlanc, M.; Ivers, H.; Savard, J.; Espie, C.A.; Mérette, C.; Baillargeon, L.; Grégoire, J.P. The natural history of insomnia: A population-based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewa, L.H.; Thibaut, B.; Pattison, N.; Campbell, S.J.; Woodcock, T.; Aylin, P.; Archer, S. Treating insomnia in people who are incarcerated: A feasibility study of a multicomponent treatment pathway. Sleep Adv. J. Sleep Res. Soc. 2024, 5, zpae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, K.A.; Hirshman, J.; Hernandez, B.; Stefanick, M.L.; Hoffman, A.R.; Redline, S.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Stone, K.; Friedman, L.; Zeitzer, J.M.; et al. When a gold standard isn’t so golden: Lack of prediction of subjective sleep quality from sleep polysomnography. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 123, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolsen, M.R.; Soehner, A.M.; Morin, C.M.; Bélanger, L.; Walker, M.; Harvey, A.G. Sleep the night before and after a treatment session: A critical ingredient for treatment adherence? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsrud, K.; Vaaler, A.; Morken, G.; Kallestad, H.; Almvik, R.; Palmstierna, T.; Güzey, I.C. The predictive properties of violence risk instruments may increase by adding items assessing sleep. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Waitlist | CBT-I | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.1 ± 12.0 | 38.9 ± 13.0 |

| Use of sleep medication | 7 (46.7%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | ||

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 4 (25.0%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Periodic explosive disorder | 5 (31.3%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| Substance use disorder | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (40%) |

| Borderline personality disorder | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Personality disorder NOS | 3 (18.8%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (33.3%) |

| Paraphilia/pedophilia | 3 (18.8%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Outcome measures | ||

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | 15.8 ± 4.3 | 18.0 ± 3.6 |

| General psychopathology (SCL-90) | 102.4 ± 55.9 | 108.7 ± 48.4 |

| Hostility (SCL-90 subscale) | 7.6 ± 5.9 | 7.3 ± 4.4 |

| Impulsivity (BIS) | 73.1 ± 12.7 | 70.2 ± 10.1 |

| Aggression (AQ) | 85.0 ± 23.1 | 95.9 ± 14.5 |

| Sleep efficiency (actigraphy) | 75.6 ± 16.3 | 79.0 ± 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Veen, M.M.; Boersma, G.J.; Karsten, J.; Lancel, M. Treatment of Insomnia in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030302

Van Veen MM, Boersma GJ, Karsten J, Lancel M. Treatment of Insomnia in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(3):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030302

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Veen, Maaike Marina, Gretha Johanna Boersma, Julie Karsten, and Marike Lancel. 2025. "Treatment of Insomnia in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Brain Sciences 15, no. 3: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030302

APA StyleVan Veen, M. M., Boersma, G. J., Karsten, J., & Lancel, M. (2025). Treatment of Insomnia in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030302