Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and End-Stage Renal Failure: A Case Report and a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

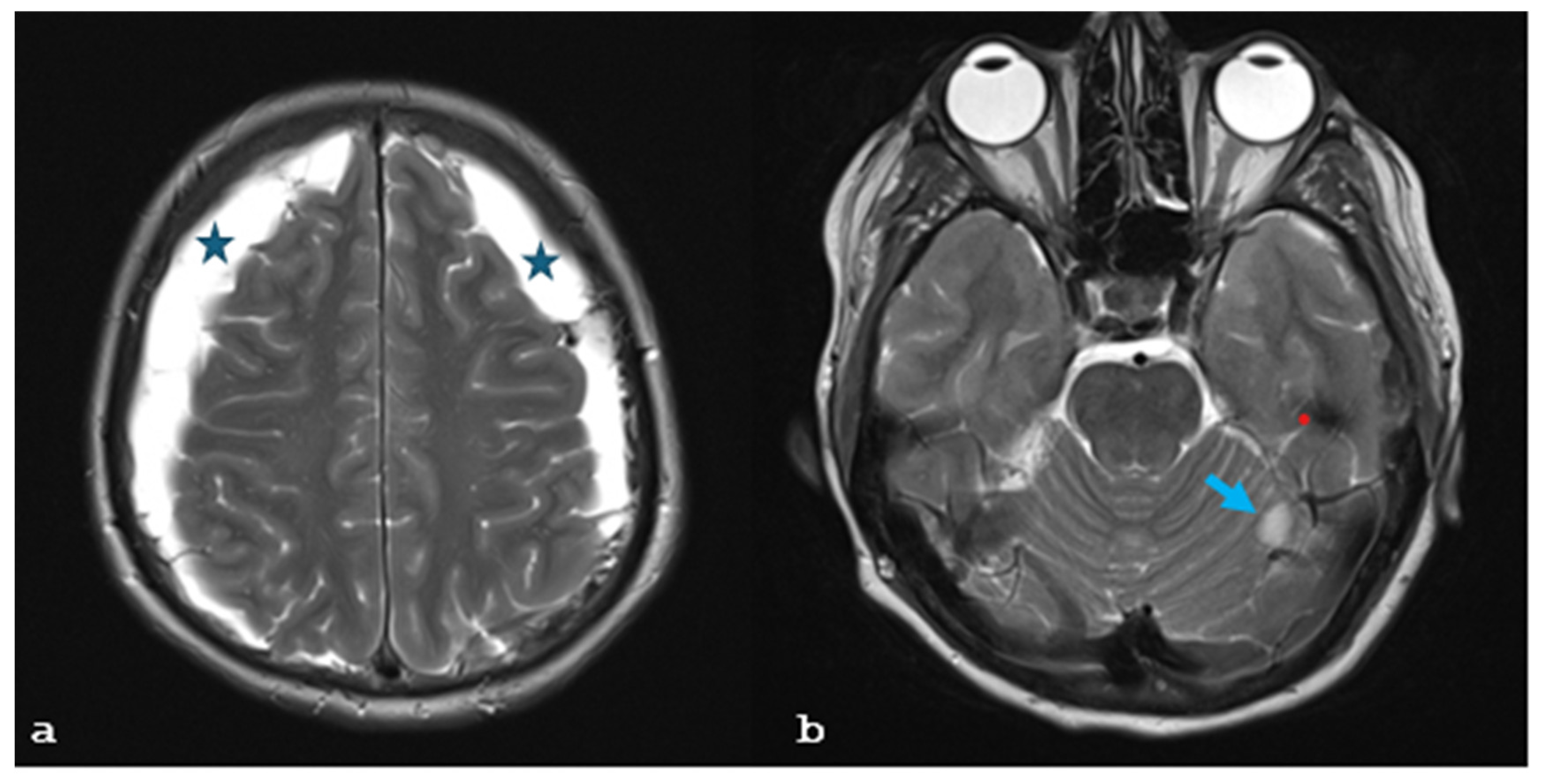

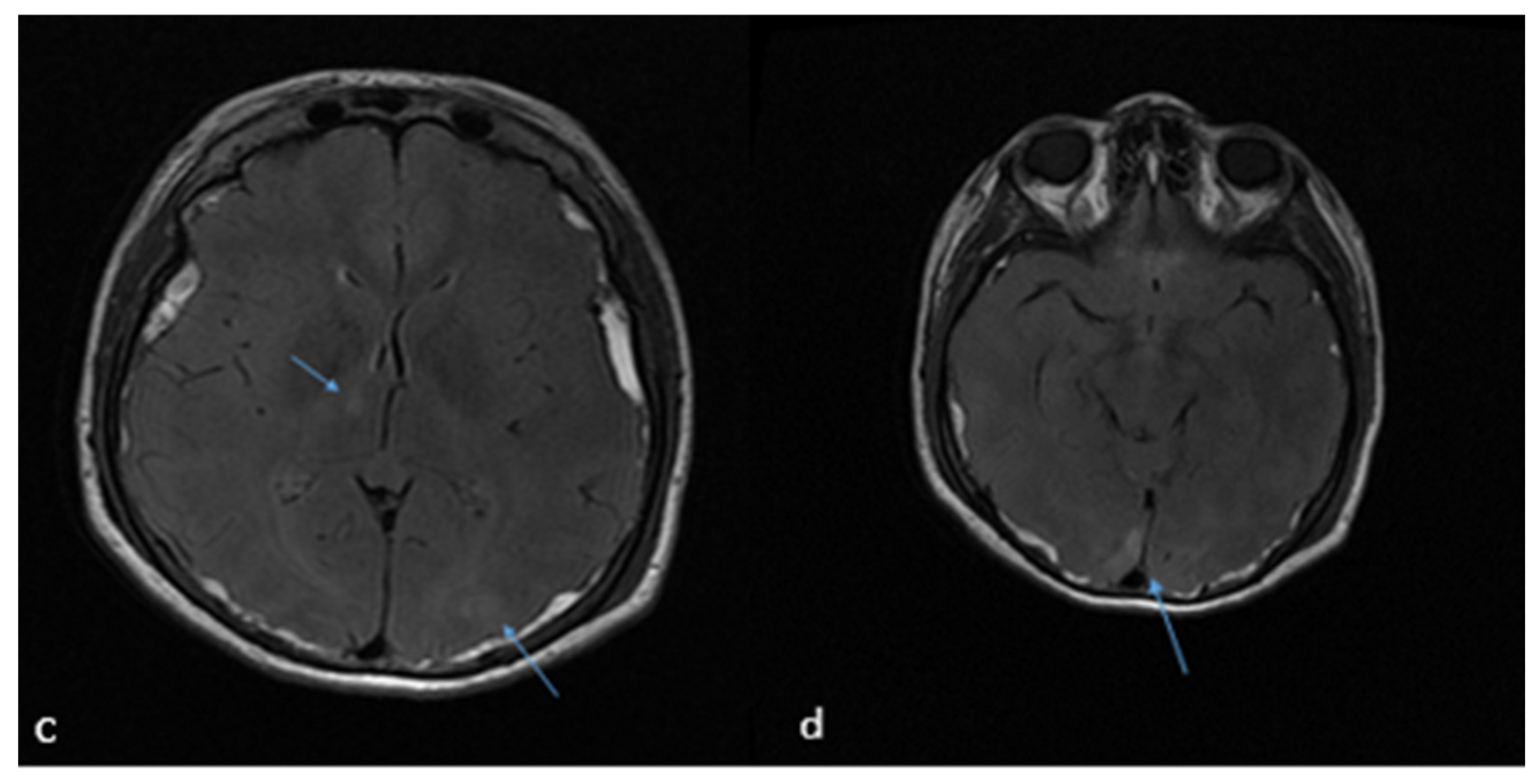

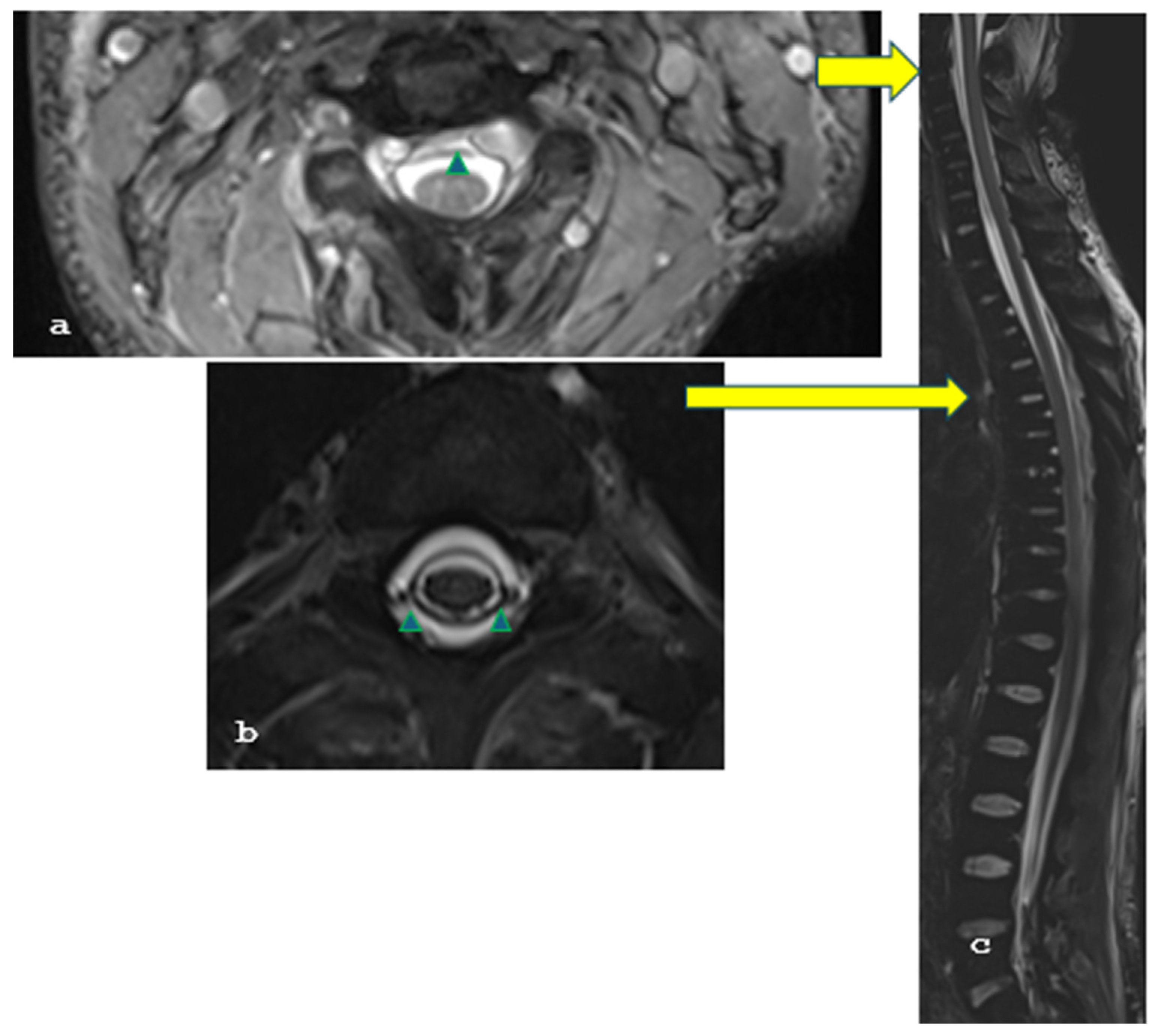

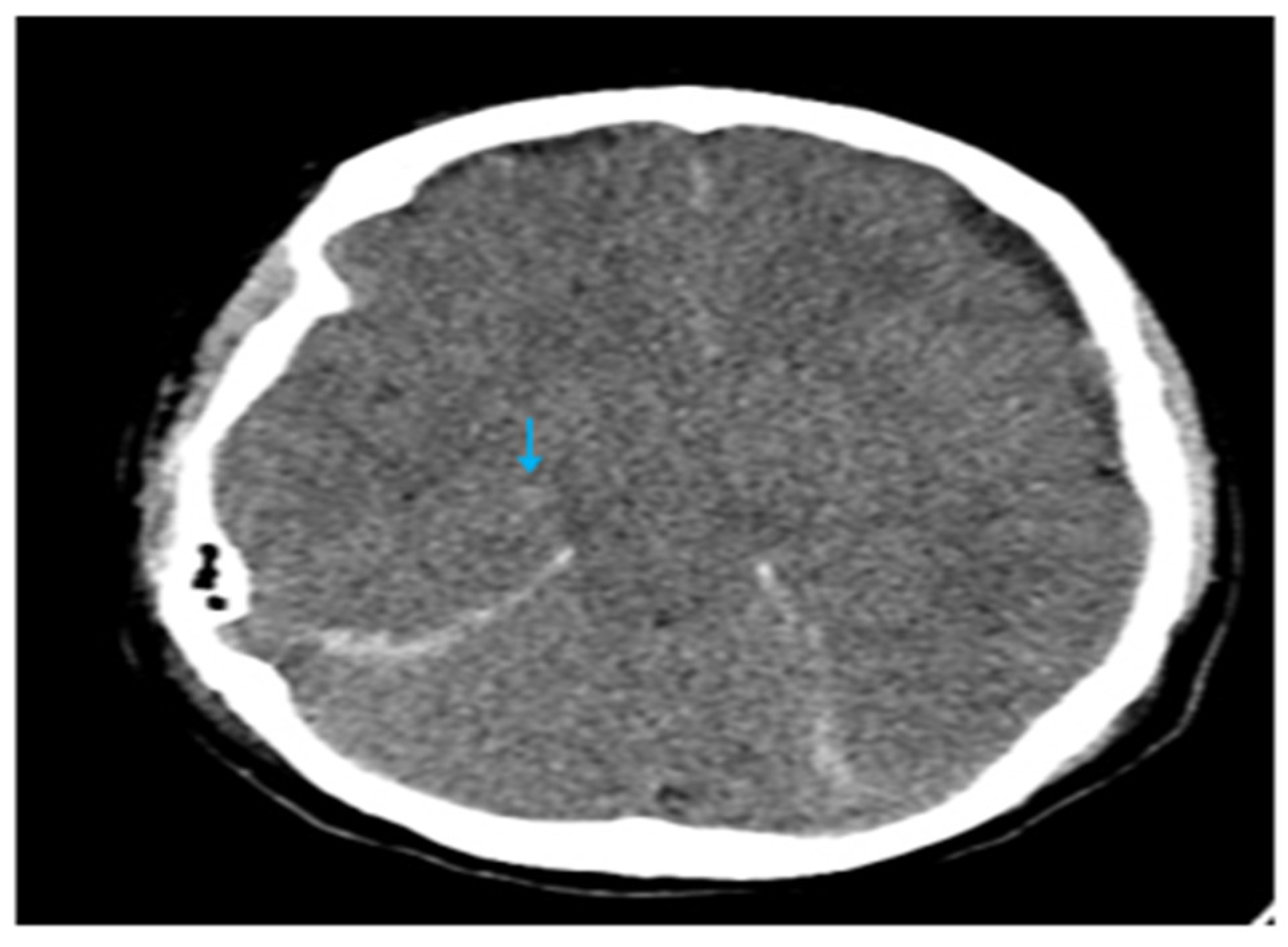

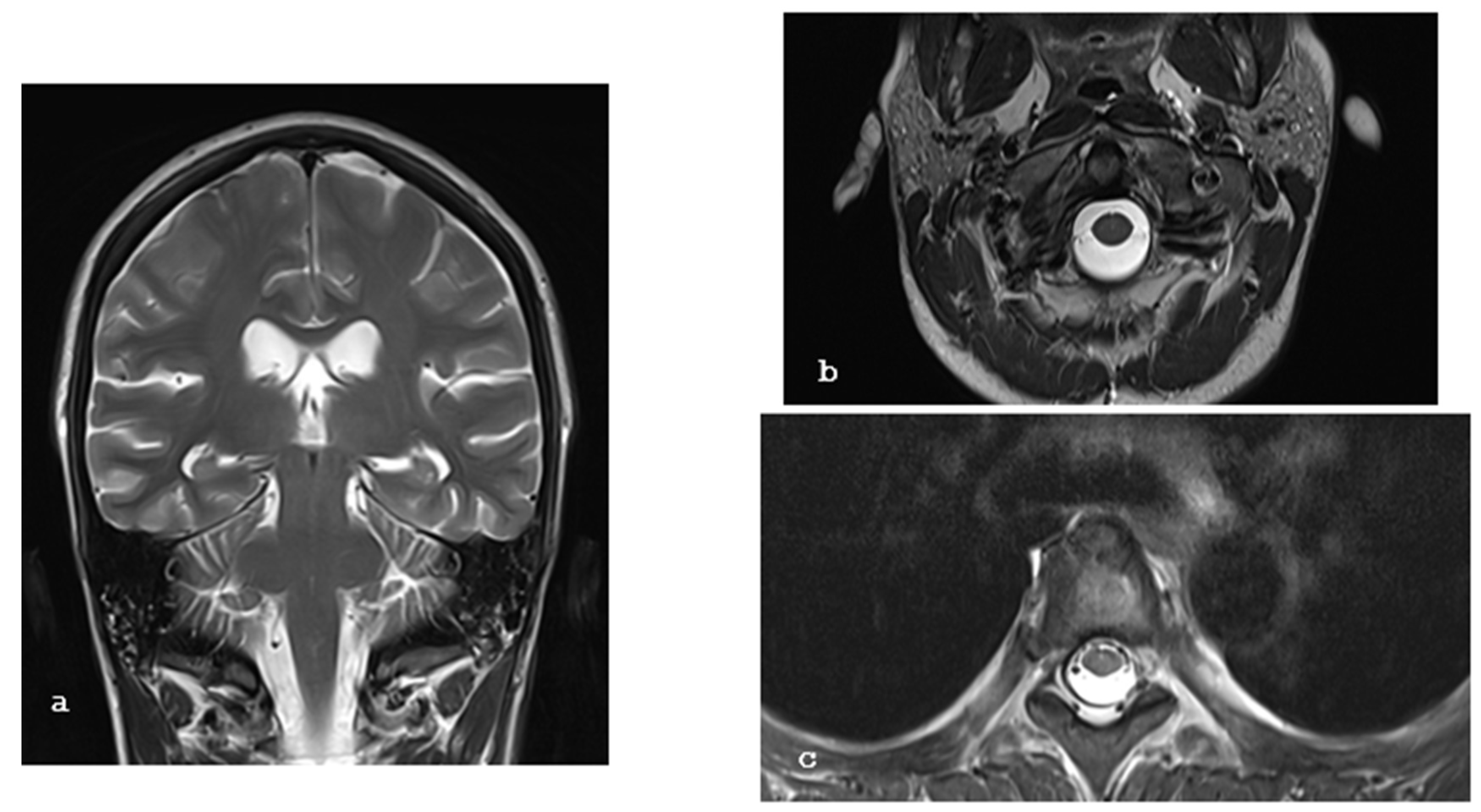

2. Case Report

3. Literature Search

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESRF | end-stage renal failure |

| SIH | spontaneous intracranial hypotension |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| CT | computed tomography |

| PRES | posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome |

| ESRD | end-stage renal disease |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

References

- McKee, K.E.; Etherton, M.R.; Lovitch, S.B.; Gupta, A.S.; Micalizzi, D.S.; Tierney, T.; Wadleigh, M.; Vaitkevicus, H. A Man in His 40s with Headache, Lethargy, and Altered Mental Status. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brouns, R.; De Deyn, P.P. Neurological complications in renal failure: A review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2004, 107, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonello, S.; Grossi, U.; Trincia, E.; Zanus, G. First-line steroid treatment for spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schievink, W.I.; Marcel Maya, M. Hemodialysis headache and presyrinx in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Neurology 2010, 75, 1847–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa Melo, E.; Pedrosa, R.P.; Carrilho Aguiar, F.; Valente, L.M.; Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A. Dialysis headache: Characteristics, impact and cerebrovascular evaluation. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2022, 80, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Addad, D.I.; Efendizade, A.; Grigorian, A.; Hewitt, K.; Velayudhan, V. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, D.; Mea, E.; Chiapparini, L.; Ciceri, E.; Nappini, S.; Savoiardo, M.; Castelli, M.; Cortelli, P.; Carriero, M.R.; Leone, M.; et al. Spontaneous low cerebrospinal pressure: A mini review. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 25 (Suppl. S3), S135–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Song, J.; Huq, A.M.; Timilsina, S.; Gershwin, M.E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, J.P.; Morreale, V.M. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension complicated by diffuse cerebral edema and episodes of severely elevated intracranial pressure: Illustrative case. J. Neurosurg. Case Lessons 2021, 2, CASE21118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pugliese, S.; Finocchi, V.; Borgia, M.L.; Nania, C.; Della Vella, B.; Pierallini, A.; Bozzao, A. Intracranial hypotension and PRES: Case report. J. Headache Pain 2010, 11, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benna, P.; Lacquaniti, F.; Triolo, G.; Ferrero, P.; Bergamasco, B. Acute neurologic complications of hemodialysis: Study of 14,000 hemodialyses in 103 patients with chronic renal failure. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1981, 2, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geocadin, R.G. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.; Schmutzhard, E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandragiri, S.; Raju, S.B.; Mandarapu, S.B.; Goli, R.; Nimmagadda, S.; Uppin, M. A Clinicopathological Study of 267 Patients with Diabetic Kidney Disease Based on the Renal Pathology Society—2010 Classification System. Indian J. Nephrol. 2020, 30, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Database | Search String | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“Chronic renal failure”) OR (“End-stage renal failure”)) OR (“hemodialysis”)) AND ((“Spontaneous intracranial hypotension”) OR (“Craniospinal hypotension”)) | 1 |

| Scopus | (“Chronic renal failure” OR “end-stage renal failure” OR “hemodialysis”) AND (“Spontaneous intracranial hypotension” OR “craniospinal hypotension”) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) | 20 |

| Dimensions | (“Chronic renal failure” OR “end-stage renal failure” OR “hemodialysis”) AND (“spontaneous intracranial hypotension” OR “craniospinal hypotension”); filter: article | 296 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paterakis, K.; Brotis, A.; Kalogeras, A.; Karagianni, M.; Spiliotopoulos, T.; Arvaniti, C.; Petsiti, A.; Vlychou, M.; Dardiotis, E.; Arnaoutoglou, E.; et al. Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and End-Stage Renal Failure: A Case Report and a Literature Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030296

Paterakis K, Brotis A, Kalogeras A, Karagianni M, Spiliotopoulos T, Arvaniti C, Petsiti A, Vlychou M, Dardiotis E, Arnaoutoglou E, et al. Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and End-Stage Renal Failure: A Case Report and a Literature Review. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(3):296. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030296

Chicago/Turabian StylePaterakis, Konstantinos, Alexandros Brotis, Adamantios Kalogeras, Maria Karagianni, Theodosios Spiliotopoulos, Christina Arvaniti, Argiro Petsiti, Marianna Vlychou, Efthimios Dardiotis, Eleni Arnaoutoglou, and et al. 2025. "Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and End-Stage Renal Failure: A Case Report and a Literature Review" Brain Sciences 15, no. 3: 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030296

APA StylePaterakis, K., Brotis, A., Kalogeras, A., Karagianni, M., Spiliotopoulos, T., Arvaniti, C., Petsiti, A., Vlychou, M., Dardiotis, E., Arnaoutoglou, E., & Fountas, K. N. (2025). Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and End-Stage Renal Failure: A Case Report and a Literature Review. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030296