Hormonal and Cytokine Imbalances Promote a Proinflammatory Profile in Institutionalized Elderly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

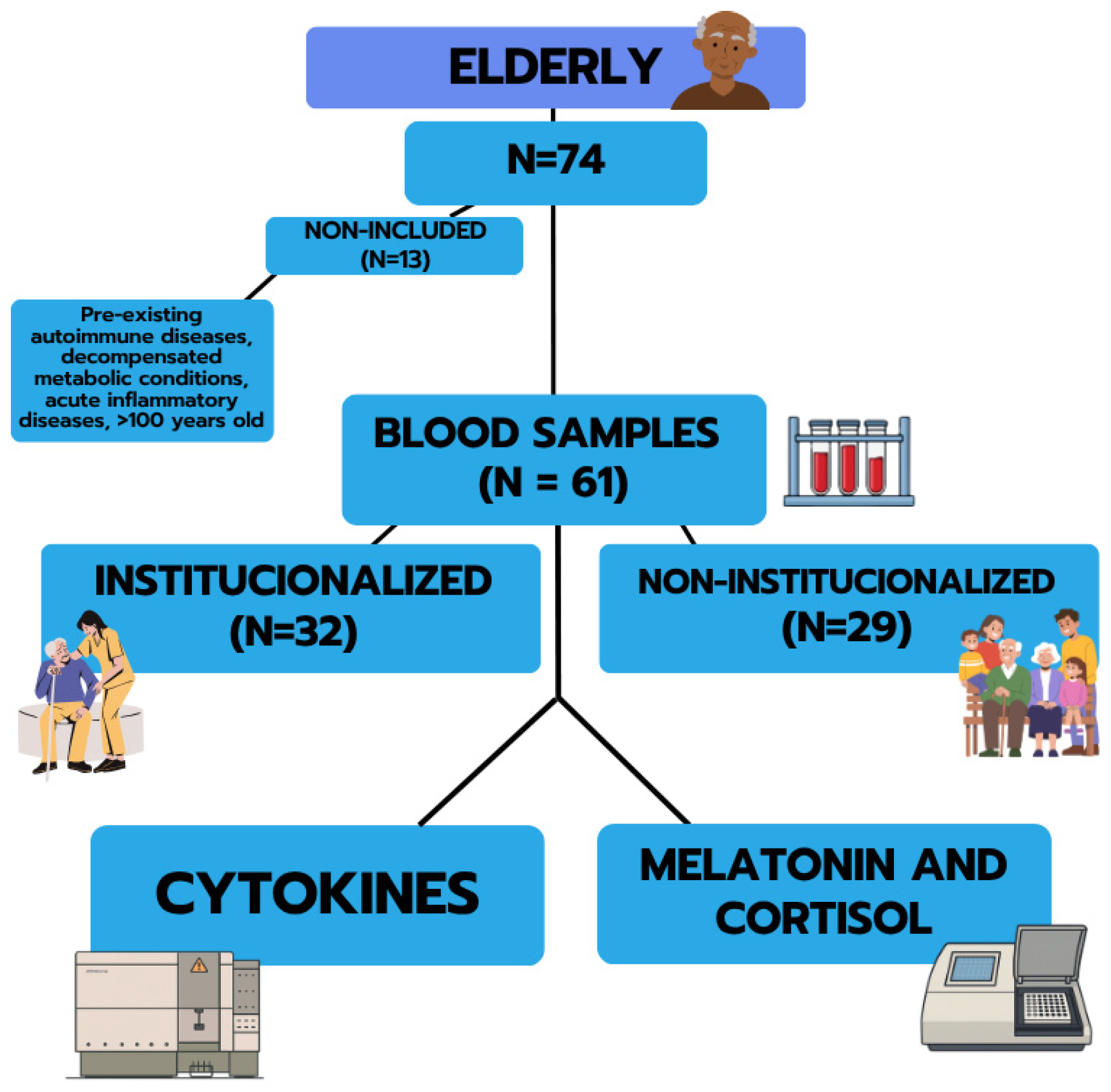

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Cytokines Determination

2.4. Melatonin and Cortisol Determination

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Patients

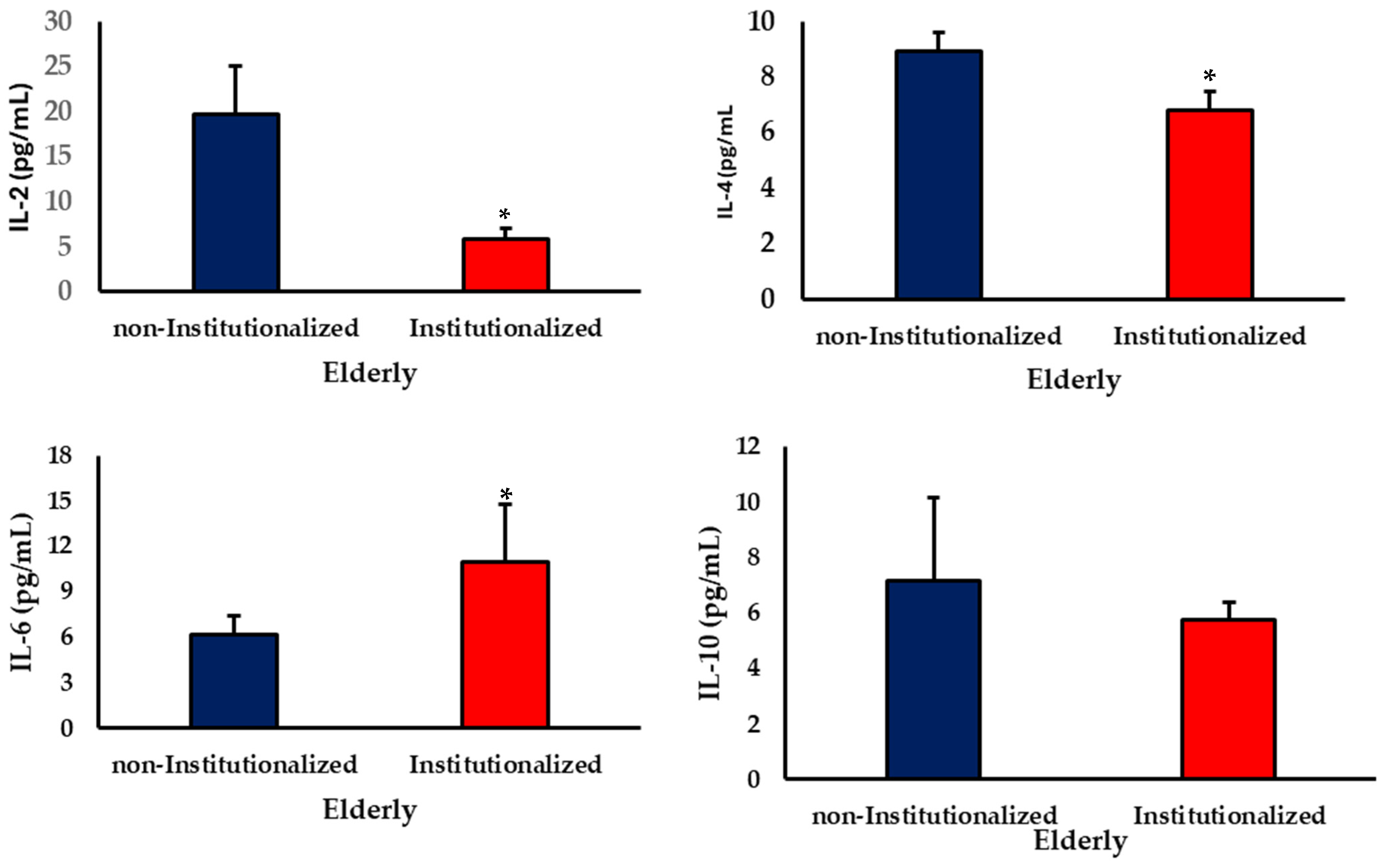

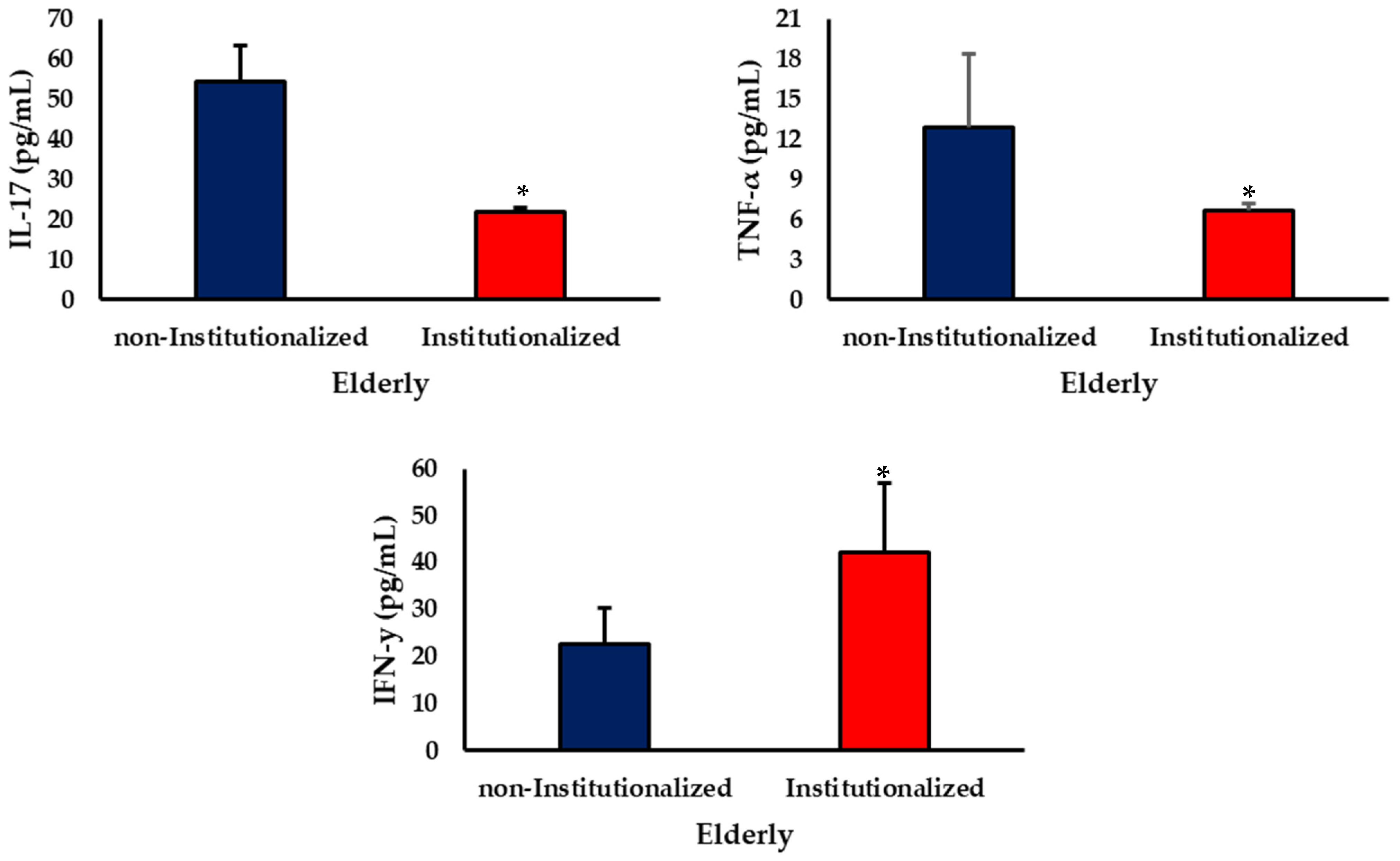

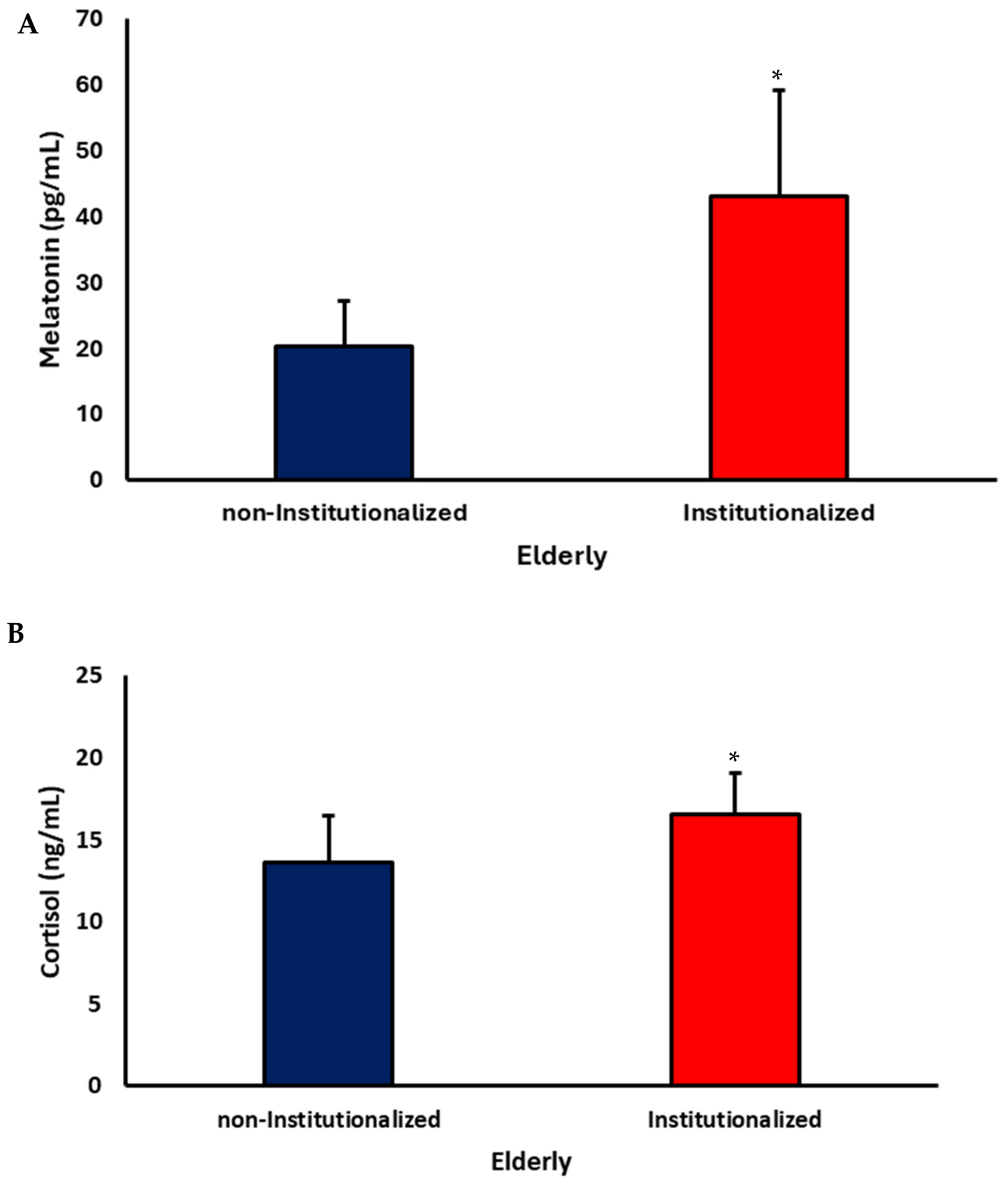

3.2. Cytokine Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A New Immune–Metabolic Viewpoint for Age-Related Diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fülöp, T.; Larbi, A.; Witkowski, J.M. Human Inflammaging. Gerontology 2019, 65, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and Aging: Signaling Pathways and Intervention Therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Eustress: On Constant Alert for Redox Homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Miceli, D.; Gray, K.; Sorenson, M.R.; Holtzclaw, B.J. Immunosenescence and Infectious Disease Risk Among Aging Adults: Management Strategies for FNPs to Identify Those at Greatest Risk. Adv. Fam. Pract. Nurs. 2023, 5, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Schurman, S.H.; Bektas, A.; Kaileh, M.; Roy, R.; Wilson, D.M., III; Sen, R.; Ferrucci, L. Aging and Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Chen, P.; Qi, C. Circadian Rhythm Regulation in the Immune System. Immunology 2024, 171, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, P.; Gibbs, J.E.; Rainger, G.E.; Chimen, M. Changes in Circadian Rhythms Dysregulate Inflammation in Ageing: Focus on Leukocyte Trafficking. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 673405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnarić, L.T.; Bosnić, Z.; Guljaš, S.; Vučić, D.; Kurevija, T.; Volarić, M.; Martinović, I.; Wittlinger, T. Low Psychological Resilience in Older Individuals: An Association with Increased Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and the Presence of Chronic Medical Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogart, K.; Engeland, C.G.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Harrington, K.D.; Knight, E.L.; Zhaoyang, R.; Scott, S.B.; Graham-Engeland, J.E. The Association Between Loneliness and Inflammation: Findings from an Older Adult Sample. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 801746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, J.K.; Ismail, A.H.; Ibrahim, R.; Hassan, N.H. Factors Associated with Frailty in Older Adults in Community and Nursing Home Settings: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arroyo, C.; Molinero, N.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Gut Microbiota and Nutrition in Nursing Homes: Challenges and Translational Approaches for Healthy Aging. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Di Matteo, A.; Farah, S.; Di Carlo, M. Inflammaging and Frailty in Immune-Mediated Rheumatic Diseases: How to Address and Score the Issue. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szataniak, I.; Packi, K. Melatonin as the Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation and Immune Dysregulation: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, M.I.; Colling, C.; Dichtel, L.E. Adrenal Aging and Its Effects on Stress Response and Immunosenescence. Maturitas 2023, 168, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadhan, R.; Walston, J.; Cappola, A.R.; Carlson, M.C.; Wand, G.S.; Fried, L.P. Higher Levels and Blunted Diurnal Variation of Cortisol in Frail Older Women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R. Aging, Melatonin, and the Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Networks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, O.; Akgun-Unal, N.; Baltaci, A.K. Unveiling Mysteries of Aging: The Potential of Melatonin in Preventing Neurodegenerative Diseases in Older Adults. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, D.C.H.; Fujimori, M.; de Queiroz, A.A.; Borges, M.D.; Magalhães Neto, A.M.; de Camargos, P.J.V.; Ribeiro, E.B.; França, E.L.; Honorio-França, A.C.; Fagundes-Triches, D.L.G. Melatonin and Cytokines Modulate Daily Instrumental Activities of Elderly People with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Giménez, V.M.; de las Heras, N.; Lahera, V.; Tresguerres, J.A.F.; Reiter, R.J.; Manucha, W. Melatonin as an Anti-Aging Therapy for Age-Related Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 888292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K.; Khan, M.I.; Ashfaq, F.; Rizvi, S.I. Crosstalk Between Aging, Circadian Rhythm, and Melatonin. Rejuvenation Res. 2023, 26, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zefferino, R.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. Molecular Links Between Endocrine, Nervous, and Immune System During Chronic Stress. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. Circadian Rhythm Regulates the Function of Immune Cells and Participates in the Development of Tumors. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcau, M.C.; Jurcau, A.; Cristian, A.; Hogea, V.O.; Diaconu, R.G.; Nunkoo, V.S. Inflammaging and Brain Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Chan, J.H.Y.; Chan, R.S.M.; Sham, A.; Ho, S.C.; Woo, J. Predictive Value of the GLIM Criteria in Chinese Community-Dwelling and Institutionalized Older Adults Aged 70 Years and Over. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Arguvanlı Çoban, S.; Şahin, H.; Ongan, D. A Comparison of Cognitive Functions and Nutritional Status in Nursing Home Residents and Community-Dwelling Elderly. Alpha Psychiatry 2021, 22, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarra, F.; Campolo, F.; Franceschini, E.; Carlomagno, F.; Venneri, M.A. Gender-Specific Impact of Sex Hormones on the Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, W.; Zhao, E.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Wu, X. Social Capital, Health Status, and Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being among Older Adults: A Comparative Study of Community Dwellings and Nursing Homes. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante Ubilla, M.A.; Plaza, E. Influence of Oral Health and Social Support on Life Satisfaction in Chilean Older Adults: Evidence from a Comprehensive Factor Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.; Alves, E.; Guedes de Pinho, L.; Fonseca, C. Functional Capacity of Institutionalized Older People and Their Quality of Life, Depressive Symptoms and Feelings of Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3150–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyani, P.; Christodoulou, R.; Vassiliou, E. Immunosenescence: Aging and Immune System Decline. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, D.; Añé-Kourí, A.L.; Barzilai, N.; Caruso, C.; Cho, K.-H.; Fontana, L.; Franceschi, C.; Frasca, D.; Ledón, N.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Aging and Chronic Inflammation: Highlights from a Multidisciplinary Workshop. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, E.K.; Chung, K.W.; Chung, S.; Lee, B.; Seo, A.Y.; Chung, J.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Im, E.; et al. Redefining Chronic Inflammation in Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Proposal of the Senoinflammation Concept. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W. IFN-Aging: Coupling Aging with Interferon Response. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 870489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and age-related diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, M.-J.; Grenier, S.; Plusquellec, P. Exploring Interindividual Variability in Resilience to Stress: Social Support, Coping Styles, and Diurnal Cortisol in Older Adults. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velpen, I.F.; de Feijter, M.; Raina, R.; Özel, F.; Perry, M.; Ikram, M.A.; Vernooij, M.W.; Luik, A.I. Psychosocial Health Modifies Associations Between HPA-Axis Function and Brain Structure in Older Age. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 153, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassamal, S. Chronic Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Depression: An Overview of Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Emerging Anti-Inflammatories. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touitou, Y.; Reinberg, A.; Touitou, D. Association between Light at Night, Melatonin Secretion, Sleep Deprivation, and the Internal Clock: Health Impacts and Mechanisms of Circadian Disruption. Life Sci. 2017, 173, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiño, J.A.; Gamundí, A.; Akaarir, M.; Cañellas, F.; Rial, R.; Ballester, N.; Nicolau, M.C. Effects of Differences in the Availability of Light upon the Circadian Rhythms of Institutionalized Elderly. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, O.S.; Iob, E.; Ajnakina, O.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Steptoe, A. Immune-Neuroendocrine Patterning and Response to Stress: A Latent Profile Analysis in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 115, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslehi, M.; Moazamiyanfar, R.; Dakkali, M.S.; Rezaei, S.; Rastegar-Pouyani, N.; Jafarzadeh, E.; Mouludi, K.; Khodamoradi, E.; Taeb, S.; Najafi, M. Modulation of the Immune System by Melatonin: Implications for Cancer Therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.M.R.; França, D.C.H.; de Queiroz, A.A.; Fagundes-Triches, D.L.G.; de Marchi, P.G.F.; Morais, T.C.; Honorio-França, A.C.; França, E.L. Polarization of Melatonin-Modulated Colostrum Macrophages in the Presence of Breast Tumor Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, D.C.H.; França, E.L.; Honório-França, A.C.; Silva, K.M.R.; Queiroz, A.A.d.; Morais, T.C.; França, E.C.H.; de Carvalho, C.N.F.; Fagundes-Triches, D.L.G.; Barbosa, A.M.P.; et al. Melatonin and Inflammatory Cytokines as Modulators of the Interaction Between Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Pregnancy-Specific Urinary Incontinence. Metabolites 2025, 15, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonian, B.J.; Hippensteel, J.A.; Abuabara, K.; Boyle, E.M.; Colbert, J.F.; Devinney, M.J.; Faye, A.S.; Kochar, B.; Lee, J.; Litke, R.; et al. Inflammation and Aging-Related Disease: A Transdisciplinary Inflammaging Framework. Geroscience 2025, 47, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero, G.; Franceschetti, L.; Bonomini, F.; Rodella, L.F.; Rezzani, R. Melatonin as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent Modulating Inflammasome Activation. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 1835195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantounou, M.; Plascevic, J.; Galley, H.F. Melatonin and Related Compounds: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Actions. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Non-Institutionalized | Institutionalized |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 29 | 32 |

| Age (y) | 74.4 ± 7.5 | 78.2 ± 8.1 |

| Gender (% female) | 12 (41.4%) | 14 (43.7%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.9 ± 5.2 | 25.4 ± 3.3 |

| Body weight (kg) | 57.0 ± 6.7 | 59.5 ± 11.3 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 77.5 ± 1.7 | 73.2 ± 2.2 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 106.2 ± 14.6 | 109.8 ± 43.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6/29 (20.7%) | 7/32 (21.8%) |

| Hypertension | 18/29 (62.1%) | 21/32 (65.6%) |

| Non-Institutionalized vs. Institutionalized | |

|---|---|

| Melatonin | r = −0.3842 |

| p = 0.2433 | |

| Cortisol | r = 0.8309 |

| p = 0.0055 * | |

| Melatonin × Cortisol | |

| non-institutionalized | r = −0.0439 |

| p = 0.9107 | |

| Institutionalized | r = 0.589 |

| p = 0.0448 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sfredo, A.d.S.; Silva, M.A.B.d.; Melo, L.V.L.; França, D.C.H.; Dantas, G.L.; Santos, W.B.d.; Fagundes-Triches, D.L.G.; Marchi, P.G.F.d.; Honorio-França, A.C.; França, E.L. Hormonal and Cytokine Imbalances Promote a Proinflammatory Profile in Institutionalized Elderly. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121310

Sfredo AdS, Silva MABd, Melo LVL, França DCH, Dantas GL, Santos WBd, Fagundes-Triches DLG, Marchi PGFd, Honorio-França AC, França EL. Hormonal and Cytokine Imbalances Promote a Proinflammatory Profile in Institutionalized Elderly. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121310

Chicago/Turabian StyleSfredo, Arce dos Santos, Marcondes Alves Barbosa da Silva, Laura Valdiane Luz Melo, Danielle Cristina Honorio França, Gabriel Lopes Dantas, Wagner Batista dos Santos, Danny Laura Gomes Fagundes-Triches, Patrícia Gelli Feres de Marchi, Adenilda Cristina Honorio-França, and Eduardo Luzía França. 2025. "Hormonal and Cytokine Imbalances Promote a Proinflammatory Profile in Institutionalized Elderly" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121310

APA StyleSfredo, A. d. S., Silva, M. A. B. d., Melo, L. V. L., França, D. C. H., Dantas, G. L., Santos, W. B. d., Fagundes-Triches, D. L. G., Marchi, P. G. F. d., Honorio-França, A. C., & França, E. L. (2025). Hormonal and Cytokine Imbalances Promote a Proinflammatory Profile in Institutionalized Elderly. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121310