Modality-Specific and Multimodal ‘Associative’ Forms of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Review of Single-Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

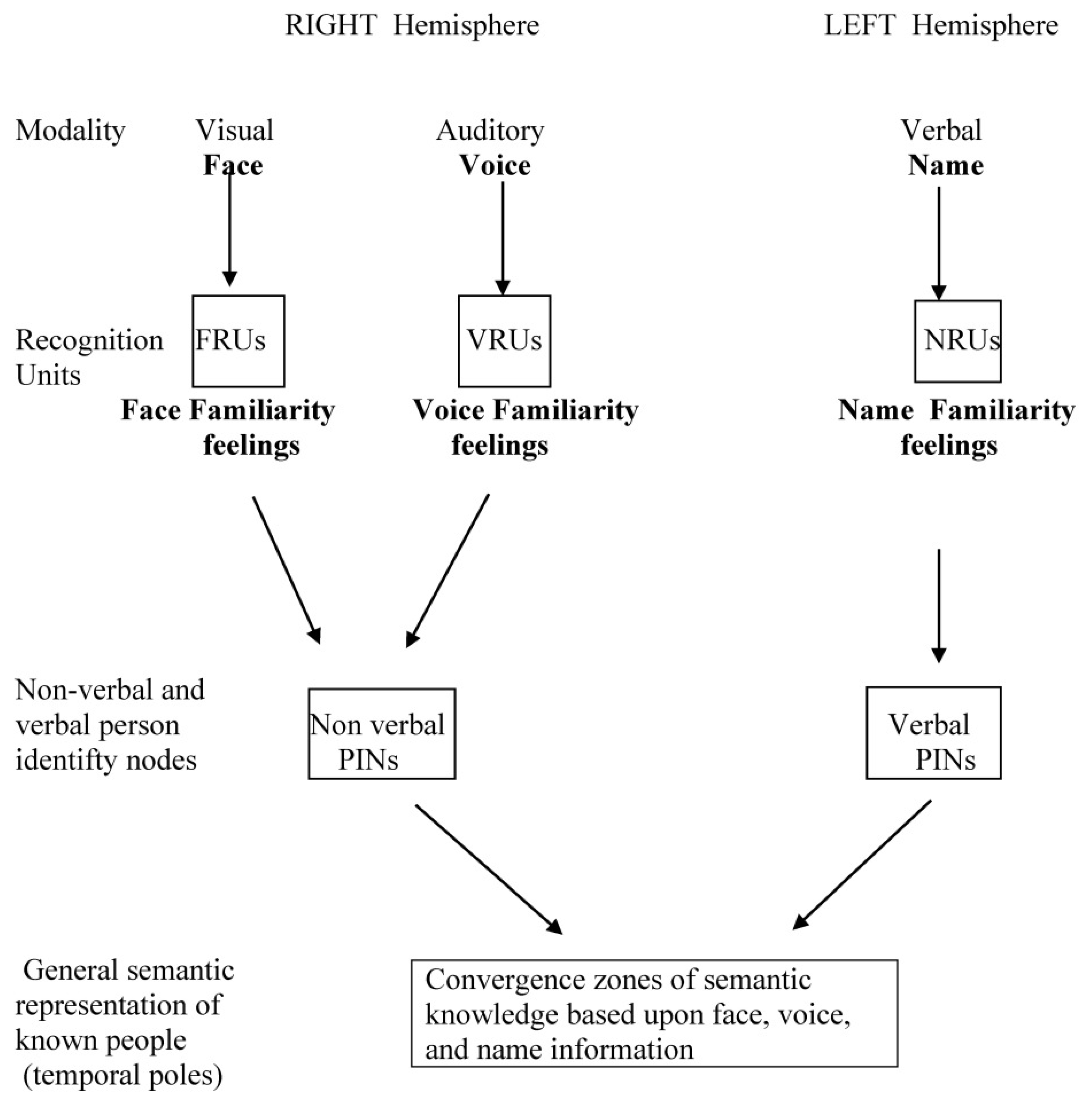

1.1. The Nature of ‘Post-Perceptual’ Face Recognition Disorders

1.2. Structural Architecture of the Person Recognition System

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

1.3. Disorders of Person Recognition That Should Be Taken into Account to Clarify the Nature of Post-Perceptual Associative Variants of Prosopagnosia

1.4. Why a Parallel Study of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders Has Rarely Been Made

1.5. Aims of the Present Review

- (a)

- Were subjects with ‘pure’ (i.e., modality-specific) forms of associative prosopagnosia or phonagnosia present in the surveyed patients?

- (b)

- Were these ‘pure’ forms a sizeable part or a small minority of the total number of patients included in the review?

- (c)

- Was the incidence of associative forms of prosopagnosia and of phonagnosia roughly similar, or was one of these defects clearly prevalent?

- (d)

- Did face and voice recognition disorders habitually co-occur in the same patients, or were they usually observed in different patients?

- (e)

- When face and voice recognition disorders co-occurred, was the sequence of their presentation randomly distributed, or did one of them usually appear first?

- (f)

- Could the assessment of name recognition disorders help to clarify the meaning of the co-occurrence of associative forms of prosopagnosia and phonagnosia?

2. Methods

- (a)

- Modality-specific associative prosopagnosia was defined as a disorder of people recognition selectively affecting familiar faces (but not the perceptual discrimination of unknown faces or the recognition of familiar voices or personal names).

- (b)

- Modality-specific associative phonagnosia was defined as a disorder of people recognition selectively affecting familiar voices (but not the perceptual discrimination of unknown voices or the recognition of familiar faces or familiar names).

- (c)

- Multimodal purely non-verbal semantic disorder of familiar people recognition was defined as a disorder of familiar people recognition through face and voice, but not through personal name.

- (d)

- Multimodal general semantic disorder of familiar people recognition was defined as a disorder of familiar people recognition through face, voice, and personal name.

Data Taken into Account for Each Patient Included in the Present Review and Tests Used to Formally Evaluate Face and Voice Recognition Disorders

- (a)

- The etiopathological diagnosis.

- (b)

- The main clinical data, including the onset of all symptoms and specifically of person recognition disorders, the relevant concomitant symptomatology, and their temporal evolution.

- (c)

- The documented anatomical lesions.

- (d)

- The face and voice recognition disorders.

- (e)

- Name recognition disorders were also recorded, when available, in the selected papers to clarify the meaning of associations between face and voice recognition disorders.

3. Results

| 1, PV | ([64]; [65]) |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis. |

| Main clinical data | Subjective complaints of inability to identify familiar people by face but not by voice. Topographical disorientation, but no general cognitive impairment, language disorders, or episodic memory disorders. No defects of visual perceptual or visual–spatial abilities. |

| Anatomical lesions | Extensive damage in the whole right temporal lobe, starting from the temporal pole. Small low-density area in the left anterior temporal lobe. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, identification, and naming were separately investigated.) No defect of face discrimination was found, but face familiarity and face identification were severely impaired. |

| Voice recognition | Severely impaired (no distinction between different components was made). |

| Name recognition | Identification moderately impaired. |

| 2. KS | ([66]) |

| Diagnosis | Right temporal lobe lobectomy performed in 1973 for epileptic activity well lateralized in the right temporal lobe. |

| Main clinical data | After the right temporal lobectomy, KS progressively developed a severe loss of memory for people, concerning all modalities of person recognition. In response to a subjective memory questionnaire, she rated her memory as very poor on anything that had to do with people (remembering faces, voices, and proper names). Her memory problems extended to famous animals, buildings, and product names, but not to autobiographical memory. |

| Anatomical lesions | Removal of the anterior 6.5 cm of the right temporal lobe, including T1, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. |

| Face recognition | Face recognition: (face familiarity and identification were taken separately into account) she obtained normal scores on face discrimination but was clearly impaired on face familiarity and identification. |

| Voice recognition | Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account: severely impaired, particularly on the Famous Voices Test. |

| Name recognition | Name familiarity and name identification mildly impaired. |

| 3. BD | ([67]) |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis. |

| Main clinical data | Subjective complaints of inability to identify through face, voice, and name people other than his wife and immediate family and close friends. The patient was also unable to identify members of living categories and showed a severe topographical disorientation. No general cognitive impairment, language disorders, or visual perceptive and visual–spatial disorders, but mild memory impairment. |

| Anatomical lesions | Low-density area in the right temporal lobe involving posterior aspects of the superior temporal gyrus (CT scan). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) No defect of face matching, moderate impairment of face familiarity, and severe impairment of face identification and naming. |

| Voice recognition | Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account: he showed some covert familiarity associated with a severely impaired identification of famous voices. |

| Name recognition | Name familiarity and name identification mildly impaired. |

| 4. VH | ([68]) |

| Diagnosis | Right-sided variant of semantic dementia? |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing people by face. This difficulty was initially improved by hearing their voice, but this compensation progressively disappeared. Minor difficulty with memory. No intellectual, language, or visuo-perceptual disorder and a very mild memory deficit. |

| Anatomical lesions | Diffuse atrophy of the right temporal lobe, with sparing of the superior temporal gyrus and the hippocampal region (MRI). |

| Face recognition | Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account: face discrimination was intact, but she was moderately impaired on familiarity judgement and severely impaired on face identification. |

| Voice recognition | Not formally tested. Initially clinically spared but worsened with the progression of the disease. |

| Name recognition | Name familiarity and name identification mildly impaired. |

| 5. Maria | ([69]) |

| Diagnosis | Semantic dementia with greater right temporal lobe atrophy. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing familiar people by face (only initially improved by hearing their voice), followed by impaired visual recognition of common objects, anomia, and semantic paraphasias, but spared verbal semantic knowledge. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral widening of the posterior portions of the lateral ventricles, greater on the right (MRI). Bilateral blood-flow reduction (SPECT). |

| Face recognition | Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account: the severe face recognition deficits were mainly ‘associative’, but she was also impaired on some ‘apperceptive’ visual tasks. |

| Voice recognition | not formally tested, but hearing the voice of a familiar person did not improve identification. Furthermore, the patient no longer answered the telephone because she failed to recognize the callers from their voices. even if they were family members. |

| Name recognition | Mildly impaired. Person recognition was markedly improved by supplying the person’s proper name. |

| 6. Emma | ([70]) |

| Diagnosis | Right-sided variant of semantic dementia? |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing familiar people by face This defect initially improved by hearing the voice, but this compensation quickly disappeared. No general cognitive impairment, amnesia, apraxia, or visual–spatial defects. |

| Anatomical lesions | The right temporal lobe was more atrophic than the left one, where atrophy was still marginal. The atrophy encroached almost exclusively upon the anterior and inferior aspects of the right temporal lobe, leaving the posterior aspects virtually untouched. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) She obtained good results on apperceptive tasks but was severely impaired on face familiarity and identification tasks. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) The patient showed no apperceptive defects, being able to guess the speaker’s gender and approximate age but was unable to identify the voice of highly familiar speakers. |

| Name recognition | Identification moderately impaired. |

| 7. XY | ([71]) |

| Diagnosis | Right-sided variant of semantic dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing familiar people by face (improved by hearing their voice) and impaired smell recognition; some word-finding difficulty. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral atrophy of the mesial temporal lobes, more pronounced on the right (MRI). Severe decreased perfusion in the entire right temporal lobe (SPECT). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination and identification were separately investigated.) The patient showed no apperceptive defect but was severely impaired on the identification of famous faces. |

| Voice recognition | Was clinically intact but had not been formally tested. |

| Name recognition | Was intact. |

| 8. Patient 1 [38] | (subject 08 in [72] and subject B-AT2 in [40].) |

| Diagnosis | Severe closed head injury and right temporal lobe resection. |

| Main clinical data | The patient could not recognize familiar faces but has had no visual field defects and no symptoms of topographagnosia. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral anterior temporal damage, involving more of the right than the left hemisphere and sparing the lingual and fusiform gyri bilaterally. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) The patient showed moderate defects of face discrimination and severe defects of face familiarity and identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) Voice discrimination was preserved, whereas voice recognition was impaired. |

| Name recognition | Not investigated. |

| 9. CO | ([73]). |

| Diagnosis | Right-sided variant of semantic dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing familiar people by face, improved by hearing their voice No general cognitive impairment or disorders of language, episodic memory, executive functions, visual perception, or visual–spatial abilities. |

| Anatomical lesions | Atrophy prevalent in the antero-inferior parts of the right temporal lobe (MRI), with severe hypoperfusion restricted to the anterior parts of the right temporal lobe (SPECT). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) CO showed no defects of face discrimination but a moderate impairment on face familiarity and a severe impairment on face identification and naming. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) Voice recognition was as impaired as face recognition. |

| Name recognition | Normal. |

| 10. FG | ([74]). |

| Diagnosis | Right-sided variant of semantic dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty recognizing familiar people by face (improved by hearing the voice). Along with his face-recognition deficit, he also exhibited mild visual agnosia and mild episodic memory, visuo-perceptual, and naming difficulties. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral atrophy of the right fusiform gyrus and parahippocampal cortex, with relative sparing of the temporo-polar cortex. The extent of the atrophy was far more extensive in the right than in the left hemisphere. |

| Face recognition | Face configurational processing, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account: A mild impairment was found on face configurational processing, whereas face familiarity was moderately impaired, and face identification and naming were severely impaired. |

| Voice recognition | Clinically intact but not formally tested. |

| Name recognition | Normal. |

| 11. JT | ([75]). |

| Diagnosis | Behavioral variant of FTD with prevalence of right temporal lobe atrophy. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive change in personality, with loss of empathy and unconcern about others, followed by difficulty in recognizing familiar people through all modalities and food items. Deterioration of semantic memory extended to the recognition of words and common objects and was accompanied by a tendency to orally examine all objects repeatedly and indiscriminately. |

| Anatomical lesions | Significant atrophy in the right temporal pole and right amygdala/anterior hippocampal complex extending to the right insula. Bilateral atrophy of the collateral sulcus–fusiform gyrus. |

| Face recognition | No difficulty with face discrimination but moderate impairment of face familiarity and severe impairment of face identification and naming. |

| Voice recognition | (Not formally tested but severely impaired). Face recognition was not improved by hearing the person’s voice. |

| Name recognition | Identification severely impaired. |

| 12. MT | ([76]). |

| Diagnosis | Semantic dementia with more pronounced right temporal lobe atrophy. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive inability to learn the faces of recent acquaintances (of which the patient was unaware). She presented deficits in recognizing faces of famous people and family members but remained able to recognize familiar people by their voice. No general cognitive deterioration or disorders of language, memory, visual perception, or visual–spatial abilities. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral atrophy of the anterior temporal lobes greater on the right side. |

| Face recognition | (Face familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) The patient was moderately impaired on face familiarity, identification, and naming. |

| Voice recognition | (Familiarity and identification of well-known voices.) MT was able to correctly discriminate between the familiar and unknown people and was able to identify her close acquaintances. |

| Name recognition | Normal. |

| 13. CD | ([77]). |

| Diagnosis | Frontotemporal dementia with prevalence of the right temporal lobe atrophy |

| Main clinical data | Progressive personality change and difficulty recognizing familiar people. No difference was noted between the different modalities of person recognition. Normal results were initially obtained on memory, attention, and visual–spatial tasks, but behavioral disorders and recognition defects rapidly worsened in the following months and were followed by stereotypic behaviors, with echolalia and palilalia, and by the development of a motor neuron disease. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral atrophy of the ventral and mesial parts of the temporal lobes, more pronounced on the right side (MRI), with extensive hypoperfusion affecting ventral and dorsal parts of the right frontal and temporal lobes (SPECT). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) Not impaired on face discrimination but impaired on face familiarity and face identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) Severely impaired on voice familiarity and identification. |

| Name recognition | Severely impaired. No difference was found in the severity of people recognition disorders tested through face, voice, and verbal definition modalities. |

| 14. RA-T2 | ([78]; [40]) |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis. |

| Main clinical data | Thirty-year-old left-handed female, who had herpes simplex encephalitis 5 years prior to testing, leaving her with right anterior temporal damage. Since recovery, she has had trouble recognizing faces, relying on body habitus, gait, and voice cues. She has mild problems with her memory but continues to function well in her work at a bank. |

| Anatomical lesions | Right anterior temporal lesion with preservation in both hemispheres of the fusiform and occipital face areas and the superior temporal sulci. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) No defect of face discrimination (apart from a mild impairment in discriminating changes in identity when expression also varied, suggesting some difficulty with invariant representations) but severe disorders of face familiarity and identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) No disorders of voice discrimination but severe defects of voice familiarity and identification. |

| Name recognition | Not investigated. |

| 15. B-AT1 | ([78]; [21]) |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis |

| Main clinical data | A 24-year-old right-handed male who, 3 years prior to testing, suffered from herpes simplex encephalitis. Since recovery, he has had extreme difficulty in recognizing faces, particularly with learning new faces, though he can recognize some family members. Furthermore, he showed poor facial recognition for family members of whom he could provide reliable semantic information. Episodic memory and mental functioning were unaffected, allowing him to attend college and hold full-time employment. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral anterior temporal lesions with preservation in both hemispheres of the fusiform and occipital face areas and the superior temporal sulci. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) The patient did well on a perceptual test of face matching but showed severe defects of face familiarity identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) The patient showed mild disorders of voice discrimination but severe defects of voice familiarity and identification. |

| Name recognition | Not investigated. |

| 16. MD | ([79]) |

| Diagnosis | Right temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Slow progressive deterioration of the ability to recognize familiar persons by face, associated with difficulties in finding and understanding names of persons and common objects. These difficulties were associated with a progressive change in behavior and personality and with a tendency towards stereotypical and compulsive behaviors, narrowed preoccupations, and irritability. |

| Anatomical lesions | Clear atrophy of the anterior parts of the temporal lobes with right lateral dominance (MRI) with hypoperfusion restricted to the anterior parts of the right temporal lobe and to the right frontal lobe, insula, and parahippocampal gyrus (PET). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) No defects of face discrimination. Moderately impaired on face familiarity and severely impaired on face identification and naming. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) The patient was severely impaired in both familiarity and identification of the voices of her relatives. |

| Name recognition | Identification severely impaired. |

| 17. QR | ([80]). |

| Diagnosis | Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Insidiously progressive behavioral decline, with impassivity and loss of empathy. Impaired voice recognition with relatively spared recognition of faces. Mild general cognitive impairment, with anomia and impaired lexical comprehension. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral frontotemporal atrophy, greater in the frontal lobes and in the right anterior temporal lobe, extending posteriorly and including the superior temporal sulcus |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) Face discrimination was normal, face familiarity was moderately impaired (due to an inflated false alarm rate), and face identification and face naming were more clearly impaired. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) Voice discrimination was normal, but voice familiarity, identification, and naming were severely impaired. QR demonstrated a clear superiority for recognition of faces versus voices. |

| Name recognition | (Familiarity) mildly impaired, |

| 18. KL | ([80]). |

| Diagnosis | Temporal variant frontotemporal lobar degeneration with right temporal lobe atrophy. |

| Main clinical data | Progressive difficulty in recognizing acquaintances, followed by progressive difficulty with word finding and topographical memory. Mild anomia. |

| Anatomical lesions | Bilateral predominantly anterior temporal lobe atrophy, more marked on the right side and in the inferior temporal cortices, including the fusiform gyrus. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) Face discrimination was normal, face familiarity was moderately impaired, and face identification and naming were severely impaired. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) Voice discrimination was normal, voice familiarity was moderately impaired, and voice identification and naming were severely impaired. |

| Name recognition | Familiarity moderately impaired. |

| 19. B-ATOT2 | ([40]; [81]) |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis. |

| Main clinical data | After the HSE episode, the patient had difficulty reading and spelling, which improved, and more enduring topographagnosic symptoms. She showed familiar people recognition disorders and obtained borderline or mildly abnormal results on visual perceptual, attentional, and memory tests. |

| Anatomical lesions | The MRI showed bilateral fusiform lesions and right-sided lesions of the lateral temporo-occipital and medial occipito-parietal cortex and of the medial aspect of the temporal pole and inferior temporal cortex. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and memory were separately investigated.) The patient showed some face configurational disorders and severe defects in face familiarity and identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice familiarity and identification were taken separately into account.) Both voice discrimination and voice recognition were impaired. |

| Name recognition | Not investigated. |

| 20. RA-T3 | ([40]; [82]). |

| Diagnosis | Herpes simplex encephalitis. |

| Main clinical data | After the HSE episode, the patient showed disorders of familiar face identification but obtained normal or borderline results on visual perceptual, attentional, and memory tests. |

| Anatomical lesions | The MRI showed an important lesion in the right anterior temporal lobe with preservation of the fusiform and occipital face areas and the superior temporal sulci in both hemispheres. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) No defect in face discrimination but severe disorders of face familiarity and identification. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account.) No defects in voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were found. |

| Name recognition | Not investigated. |

| 21. BD | ([83]) |

| Diagnosis | Right temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. |

| Main clinical data | Insidious onset of personality changes, with apathy, loss of empathy, and ritualistic behaviors accompanied by familiar people recognition defects in a context of relatively intact cognitive functions. |

| Anatomical lesions | The MRI, implemented with voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and region of interest (ROI) analyses, showed a focal atrophy of the right ATL (temporo-polar cortex and anterior parts of perirhinal and entorhinal cortices). |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) The patient showed no defects of face discrimination but was moderately impaired on face familiarity, identification, and naming. |

| Voice recognition | (Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account. The patient showed no defects of voice discrimination but was severely impaired on voice familiarity, identification, and naming. |

| Name recognition | Familiarity and identification were normal. The patient obtained normal scores on people recognition and identification through personal names when written names were presented. |

| 22. MM | ([84]) |

| Diagnosis | Ischemic stroke in right subcortical structures and right anterior temporal lobe. |

| Main clinical data | After fibrinolytic treatment, the patient progressively recovered from their right-sided stroke and was discharged without neurological focal signs. When he returned home, he noticed he was not able to recognize the voices of known singers but did not note problems in identifying the voices of his relatives. Probably he had never needed to identify them exclusively by their voice, because he interacted with them face-to-face. All neuropsychological domains except voice recognition were spared. |

| Anatomical lesions | Neuroimaging carried out by means of PET and MRI revealed two small ischemic lesions in the right subcortical region, involving lenticular and caudate nuclei and in the right temporal pole. |

| Face recognition | (Face discrimination, familiarity, and identification were separately investigated.) No defects of face discrimination, familiarity, identification, and naming were found. |

| Voice recognition | Voice discrimination, familiarity, and identification were taken separately into account. No defect was found in voice discrimination, but he was severely impaired in voice familiarity, identification, and naming. |

| Name recognition | Normal. |

3.1. Analysis of Data Reported in Table 1 for Each Variable Considered in the Present Review

3.1.1. Etiopathological Diagnosis

3.1.2. Main Clinical Data

3.1.3. Neuroanatomical Data

3.1.4. Face Recognition

3.1.5. Voice Recognition

3.1.6. Name Recognition

3.1.7. Associations and Dissociations Between Face, Voice, and Name Recognition Disorders

4. Discussion

4.1. Description of the Characteristics Shown by Patients with Modality-Specific and Multimodal Forms of Person Recognition Disorders

4.2. Other Reasons Suggesing That Some Associative Forms of Prosopagnosia and Phonagnosia Might, Indeed, Be Fragments of a More General Multimodal Semantic Disorder

5. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snowden, J.S.; Thompson, J.C.; Neary, D. Knowledge of famous faces and names in semantic dementia. Brain 2004, 127, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, J.S.; Thompson, J.C.; Neary, D. Famous people knowledge and the right and left temporal lobes. Behav. Neurol. 2012, 25, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. The format of conceptual representations disrupted in semantic dementia: A position paper. Cortex 2012, 48, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. Is the difference between right and left ATLs due to the distinction between general and social cognition or between verbal and non-verbal representations? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 51, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, S.; Baldinelli, S.; Ranaldi, V.; Fabi, K.; Cafazzo, V.; Fringuelli, F.; Silvestrini, M.; Provinciali, L.; Reverberi, C.; Gainotti, G. Famous faces and voices: Differential profiles in early right and left semantic dementia and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2017, 94, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozueta, A.; Lage, C.; García-Martínez, M.; Kazimierczak, M.; Bravo, M.; López-García, S.; Riancho, J.; González-Suarez, A.; Vázquez-Higuera, J.L.; de Arcocha-Torres, M.; et al. Cognitive and behavioral profiles of left and right semantic dementia: Differential diagnosis with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 72, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesani, V.; Narvid, J.; Battistella, G.; Shwe, W.; Watson, C.; Binney, R.J.; Sturm, V.; Miller, Z.; Mandelli, M.L.; Miller, B.; et al. Looks familiar, but I do not know who she is”: The role of the anterior right temporal lobe in famous face recognition. Cortex 2019, 115, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, K.; Borghesani, V.; Montembeault, M.; Spina, S.; Mandelli, M.L.; Welch, A.E.; Weis, E.; Callahan, P.; Elahi, F.M.; Hua, A.Y.; et al. Right temporal degeneration and socioemotional semantics: Semantic behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2022, 145, 4080–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belliard, S.; Merck, C. Is semantic dementia an outdated entity? Cortex 2024, 180, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S. The 2024 Richardson Lecture: Prosopagnosia—A Classic Neurologic Deficit Meets the Modern Era. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 52, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadollahikhales, G.; Mandelli, M.L.; Ezzes, Z.; Pillai, J.; Ratnasiri, B.; Baquirin, D.P.; Miller, Z.; de Leon, J.; Tee, B.L.; Seeley, W.; et al. Perceptual and semantic deficits in face recognition in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia 2024, 205, 109020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S.; Duchaine, B.; Albonico, A. Imagery and perception in acquired prosopagnosia: Functional variants and their relation to structure. Cortex 2025, 183, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G. Semantic and Pre-semantic Defects of Person Recognition in Semantic Dementia. A commentary to the Belliard & Merck’s paper: “Is Semantic Dementia an Outdated Entity?” Cortex 2025, 183, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, V.; Young, A. Understanding face recognition. Br. J. Psychol. 1986, 77, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H.D.; Jones, D.M.; Mosdell, N. Intra- and inter-modal repetition priming of familiar faces and voices. Br. J. Psychol. 1997, 88, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, I.; Tarr, M.J.; Moylan, J.; Skudlarski, P.; Gore, J.C.; Anderson, A.W. The Fusiform “Face Area” is Part of a Network that Processes Faces at the Individual Level. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2000, 12, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxby, J.V.; Hoffman, E.A.; Gobbini, M.I. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossion, B. Understanding face perception by means of human electrophysiology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, P.; Zatorre, R.J.; Ahad, P. Human temporal-lobe response to vocal sounds. Cogn. Brain Res. 2002, 13, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, P.; Zatorre, R.J. Adaptation to speaker’s voice in right anterior temporal lobe. NeuroReport 2003, 14, 2105–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.J.; Hanif, H.M.; Iaria, G.; Duchaine, B.C.; Barton, J.J.S. Perceptual and anatomic patterns of selective deficits in facial identity and expression processing. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 3188–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.A.; Olson, I.R. Beyond the FFA: The role of the ventral anterior temporal lobes in face processing. Neuropsychologia 2014, 61, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Hillis, A.E.; Weintraub, S.; Kertesz, A.; Mendez, M.; Cappa, S.F.; Ogar, J.M.; Rohrer, J.D.; Black, S.; Boeve, B.F.; et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011, 76, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergent, J.; Ohta, S.; Macdonald, B. Functional neuroanatomy of face and object processing: A Positron Emission Tomography study. Brain 1992, 115, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwisher, N.; McDermott, J.; Chun, M.M. The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 4302–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, G.; Puce, A.; Gore, J.C.; Allison, T. Face-specific processing in the human fusiform gyrus. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1997, 9, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegstein, K.V.; Giraud, A.-L. Distinct functional substrates along the right superior temporal sulcus for the processing of voices. NeuroImage 2004, 22, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguinness, C.; Roswandowitz, C.; von Kriegstein, K. Understanding the mechanisms of familiar voice-identity recognition in the human brain. Neuropsychologia 2018, 116, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchaine, B.; Yovel, G. A revised neural framework for face processing. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2015, 1, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.W.; Hay, D.C.; McWeeny, K.H.; Ellis, A.W.; Barry, C. Familiarity decisions for faces presented to the left and right cerebral hemispheres. Brain Cogn. 1985, 4, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Kawashima, R.; Sato, N.; Nakamura, A.; Sugiura, M.; Kato, T.; Hatano, K.; Ito, K.; Fukuda, H.; Schormann, T.; et al. Functional delineation of the human occipito-temporal areas related to face and scene processing: A PET study. Brain 2000, 123, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.; Valentine, T. Strength of visual percept generated by famous faces perceived without awareness: Effects of affective valence, response latency and visual field. Conscious. Cogn. 2005, 14, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. Different patterns of famous people recognition disorders in patients with right and left anterior temporal lesions: A systematic review. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. What the study of voice recognition in normal subjects and brain-damaged patients tells us about models of familiar people recognition. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G. Laterality effects in normal subjects’ recognition of familiar faces, voices and names. Perceptual and representational components. Neuropsychologia 2013, 51, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Renzi, E. Current issues in prosopagnosia. In Aspects of Face Processing; Ellis, H.D., Jeeves, M.A., Newcombe, F., Young, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Renzi, E.; Perani, D.; Carlesimo, G.; Silveri, M.; Fazio, F. Prosopagnosia can be associated with damage confined to the right hemisphere—An MRI and PET study and a review of the literature. Neuropsychologia 1994, 32, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.; Press, D.Z.; Keenan, J.P.; O’connor, M. Lesions of the fusiform face area impair perception of facial configuration in prosopagnosia. Neurology 2002, 58, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G.; Marra, C. Differential contribution of right and left temporo-occipital and anterior temporal lesions to face recognition disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.R.; Pancaroglu, R.; Hills, C.S.; Duchaine, B.; Barton, J.J.S. Voice Recognition in Face-Blind Patients. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lancker, D.R.; Canter, G.J. Impairment of voice and face recognition in patients with hemispheric damage. Brain Cogn. 1982, 1, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, F.; Schweinberger, S.R. Neuropsychological impairments in the recognition of faces, voices, and personal names. Brain Cogn. 2000, 44, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roswandowitz, C.; Kappes, C.; Obrig, H.; von Kriegstein, K. Obligatory and facultative brain regions for voice-identity recognition. Brain 2018, 141, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodamer, J. Die prosopagnosie. Arch. Psychiatr. Nervenkr. Z 1947, 179, 6–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.; Corrow, S.L. Recognizing and identifying people: A neuropsychological review. Cortex 2016, 75, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, A. Is the voice an auditory face? An ALE meta-analysis comparing vocal and facial emotion processing. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.W.; Frühholz, S.; Schweinberger, S.R. Face and voice perception: Understanding commonalities and differences. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, E.H.F.; Young, A.W.; Newcombe, F. A dissociation between the sense of familiarity and access to semantic information concerning familiar people. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 1991, 3, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Venneri, A.; Papagno, C. Famous face recognition and naming test: A normative study. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 23, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzozero, I.; Lucchelli, F.; Saetti, M.C.; Spinnler, H. “Whose face is this?”: Italian norms of naming celebrities. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccininni, C.; Marra, C.; Quaranta, D.; Papagno, C.; Longo, C.; Sarubbo, S.; Zigiotto, L.; Luzzi, S.; Gainotti, G. Which components of famous people recognition are lateralized? A study of face, voice and name recognition disorders in patients with neoplastic or degenerative damage of the right or left anterior temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia 2023, 181, 108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancaroglu, R.; Busigny, T.; Johnston, S.; Sekunova, A.; Duchaine, B.; Barton, J.J.S. The right anterior temporal lobe variant of prosopagnosia. J. Vis. 2011, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. Is the Right Anterior Temporal Variant of Prosopagnosia a Form of ’Associative Prosopagnosia’ or a Form of ’Multimodal Person Recognition Disorder’? Neuropsychol. Rev. 2013, 23, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S. Structure and function in acquired prosopagnosia: Lessons from a series of 10 patients with brain damage. J. Neuropsychol. 2008, 2, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busigny, T.; Van Belle, G.; Jemel, B.; Hosein, A.; Joubert, S.; Rossion, B. Face-specific impairment in holistic perception following focal lesion of the right anterior temporal lobe. Neuropsychologia 2014, 56, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, A.; Van Allen, M. Prosopagnosia and facial discrimination. J. Neurol. Sci. 1972, 15, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, D.; Piccininni, C.; Carlesimo, G.A.; Luzzi, S.; Marra, C.; Papagno, C.; Trojano, L.; Gainotti, G. Recognition disorders for famous faces and voices: A review of the literature and normative data of a new test battery. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 37, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, E. Warrington Recognition Memory Test; Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Duchaine, B.; Nakayama, K. The Cambridge Face Memory Test: Results for neurologically intact individuals and an investigation of its validity using inverted face stimuli and prosopagnosic participants. Neuropsychologia 2006, 44, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.J.S.; Keenan, J.P.; Bass, T. Discrimination of spatial relations and features in faces: Effects of inversion and viewing duration. Br. J. Psychol. 2001, 92, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreiman, J.; Papçun, G. Voice discrimination by two listener populations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985, 77, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meudell, P.R.; Northen, B.; Snowden, J.S.; Neary, D. Long term memory for famous voices in amnesic and normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 1980, 18, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lancker, D.R.; Cummings, J.L.; Kreiman, J.; Dobkin, B.H. Phonagnosia: A dissociation between familiar and unfamiliar voices. Cortex 1988, 24, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresques, J.; Poncet, M.; A Cherif, A.; Balzamo, M. Agnosia for faces: Evidence of functional disorganization of a certain type of recognition of objects in the physical world. Bull. Natl. Acad. Med. 1979, 163, 695–702. (In French) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sergent, J.; Poncet, M. From covert to overt recognition of faces in a prosopagnosic patient. Brain 1990, 113, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.W.; Young, A.W.; Critchley, E.M.R. Loss of memory for people following temporal lobe damage. Brain 1989, 112, 1469–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, J.R.; Young, A.W.; Pearson, N.A. Defective recognition of familiar people. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 1989, 6, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.J.; Heggs, A.J.; Antoun, N.; Hodges, J.R. Progressive prosopagnosia associated with selective right temporal lobe atrophy. Brain 1995, 118, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentileschi, V.; Sperber, S.; Spinnler, H. Progressive defective recognition of familiar people. Neurocase 1999, 5, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentileschi, V.; Sperber, S.; Spinnler, H. Crossmodal agnosia for familiar people as a consequence of right infero-polar temporal atrophy. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2001, 18, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.F.; Ghajarnia, M. Agnosia for familiar faces and odors in a patient with right temporal lobe dysfunction. Neurology 2001, 57, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S.; Cherkasova, M. Face imagery and its relation to perception and covert recognition in prosopagnosia. Neurology 2003, 61, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G.; Barbier, A.; Marra, C. Slowly progressive defect in recognition of familiar people in a patient with right anterior temporal atrophy. Brain 2003, 126, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubert, S.; Felician, O.; Barbeau, E.; Sontheimer, A.; Barton, J.J.; Ceccaldi, M.; Poncet, M. Impaired configurational processing in a case of progressive prosopagnosia associated with predominant right temporal lobe atrophy. Brain 2003, 126, 2537–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Rankin, K.P.; Woolley, J.D.; Rosen, H.J.; Phengrasamy, L.; Miller, B.L. Cognitive and behavioral profile in a case of right anterior temporal lobe neurodegeneration. Cortex 2004, 40, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakachi, R.; Muramatsu, T.; Kato, M.; Akiyama, T.; Saito, F.; Yoshino, F.; Mimura, M.; Kashima, H. Progressive prosopagnosia at a very early stage of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Psychogeriatrics 2007, 7, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G.; Ferraccioli, M.; Quaranta, D.; Marra, C. Cross-modal recognition disorders for persons and other unique entities in a patient with right fronto-temporal degeneration. Cortex 2008, 44, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S.; Hanif, H.; Ashraf, S. Relating visual to verbal semantic knowledge: The evaluation of object recognition in prosopagnosia. Brain 2009, 132, 3456–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busigny, T.; Robaye, L.; Dricot, L.; Rossion, B. Right anterior temporal lobe atrophy and person-based semantic defect: A detailed case study. Neurocase 2009, 15, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailstone, J.C.; Crutch, S.J.; Vestergaard, M.D.; Patterson, R.D.; Warren, J.D. Progressive associative phonagnosia: A neuropsychological analysis. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroz, D.; Corrow, S.L.; Corrow, J.C.; Barton, A.R.; Duchaine, B.; Barton, J.J.S. Localization and patterns of Cerebral dyschromatopsia: A study of subjects with prospagnosia. Neuropsychologia 2016, 89, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies-Thompson, J.; Pancaroglu, R.; Barton, J. Acquired prosopagnosia: Structural basis and processing impairments. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2014, 6, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosseddu, M.; Gazzina, S.; Borroni, B.; Padovani, A.; Gainotti, G. Multimodal face and voice recognition disorders in a case with unilateral right anterior temporal lobe atrophy. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, S.; Coccia, M.; Polonara, G.; Reverberi, C.; Ceravolo, G.; Silvestrini, M.; Fringuelli, F.; Baldinelli, S.; Provinciali, L.; Gainotti, G. Selective associative phonagnosia after right anterior temporal stroke. Neuropsychologia 2018, 116, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, P.; Zatorre, R.J.; Lafaille, P.; Ahad, P.; Pike, B. Voice-selective areas in human auditory cortex. Nature 2000, 403, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.; Van Hoesen, G.W.; Cassell, M.D.; Poremba, A. Parcellation of human temporal polar cortex: A combined analysis of multiple cytoarchitectonic, chemoarchitectonic, and pathological markers. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009, 514, 595–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, L.M.; Ross, L.A.; Olson, I.R. Sensory and semantic category subdivisions within the anterior temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, I.R.; McCoy, D.; Klobusicky, E.; Ross, L.A. Social cognition and the anterior temporal lobes: A review and theoretical framework. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, I.R.; Plotzker, A.; Ezzyat, Y. The Enigmatic temporal pole: A review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain 2007, 130, 1718–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.A.; Olson, I.R. 2010 Social cognition and the anterior temporal lobes. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 3452–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, M.A.L. Neurocognitive insights on conceptual knowledge and its breakdown. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambon Ralph, M.A.; Jefferies, E.; Patterson, K.; Rogers, T.T. The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binney, R.J.; Hoffman, P.; Ralph, M.A.L. Mapping the Multiple Graded Contributions of the Anterior Temporal Lobe Representational Hub to Abstract and Social Concepts: Evidence from Distortion-corrected fMRI. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 4227–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, J.R.; Smith, S.T.; Hadfield, J. I Recognise you but I Can’t Place you: An Investigation of Familiar-only Experiences during Tests of Voice and Face Recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 1998, 51, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.R.; Damjanovic, L. It is more difficult to retrieve a familiar person’s name and occupation from their voice than from their blurred face. Memory 2009, 17, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gainotti, G. Modality-Specific and Multimodal ‘Associative’ Forms of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Review of Single-Case Studies. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121309

Gainotti G. Modality-Specific and Multimodal ‘Associative’ Forms of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Review of Single-Case Studies. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121309

Chicago/Turabian StyleGainotti, Guido. 2025. "Modality-Specific and Multimodal ‘Associative’ Forms of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Review of Single-Case Studies" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121309

APA StyleGainotti, G. (2025). Modality-Specific and Multimodal ‘Associative’ Forms of Face and Voice Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Review of Single-Case Studies. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121309