Life Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Roles of Alcohol Consumption and Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Preliminary Analysis: Differences in Depressive Symptom Severity Across Stages of Alcohol Use

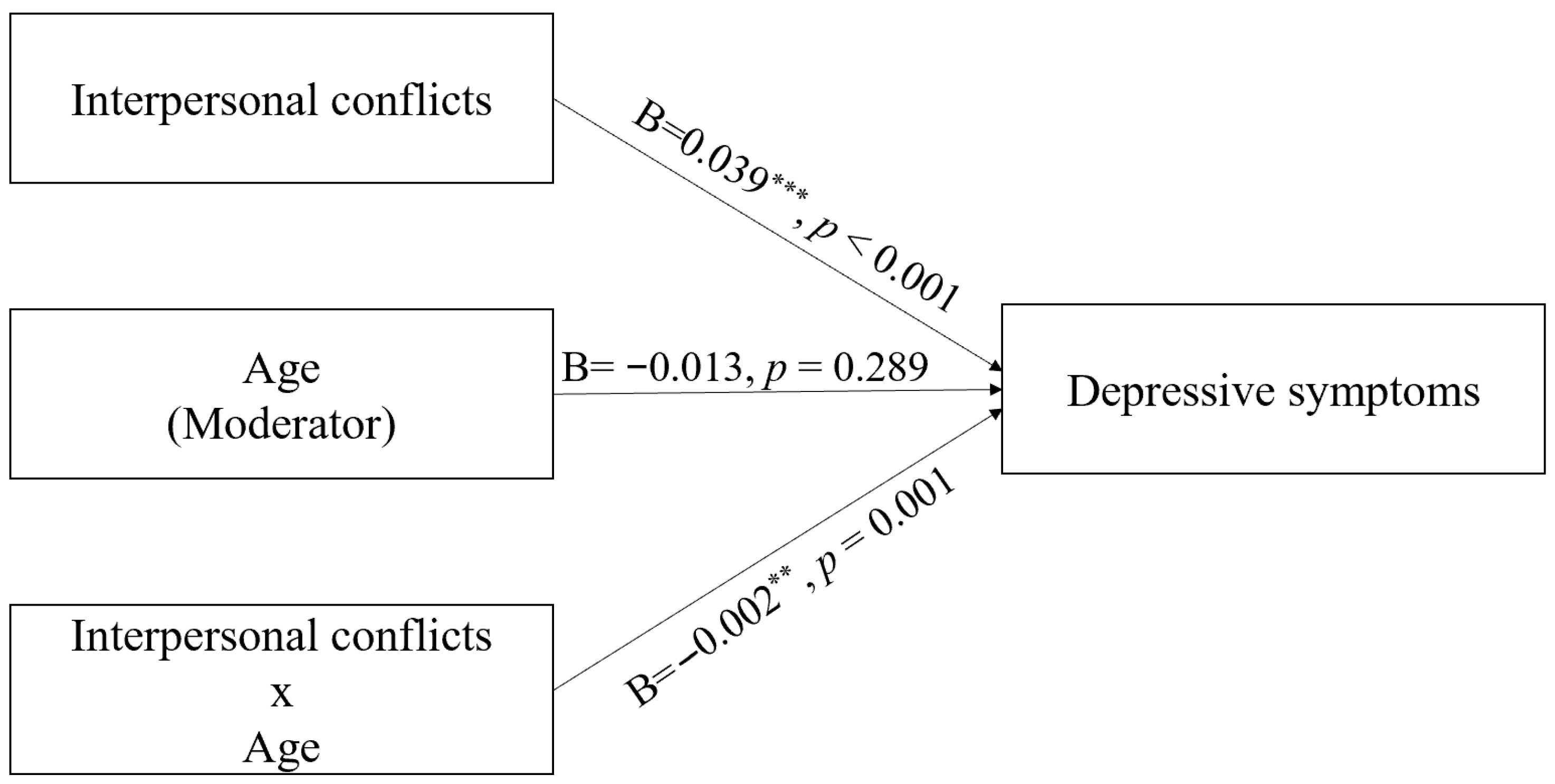

3.3. Analysis of Moderating Effects

3.3.1. Sociodemographic Factors

3.3.2. AUDIT-K Score

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

3.4.1. Global Omnibus Model Comparison

3.4.2. Clustering by Organization (GEE)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUD | Alcohol use disorder |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression |

| AUDIT-K | Korean version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test |

References

- World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/world-employment-and-social-outlook-trends-2023 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- The Leading Source of Labour Statistics. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerveld, S.E.; Bültmann, U.; Franche, R.L.; van Dijk, F.J.H.; Vlasveld, M.C.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Bruinvels, D.J.; Huijs, J.J.; Blonk, R.W.; van der Klink, J.J.; et al. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: A systematic review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2010, 20, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States. 2019. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37518849/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C. The potential of predictive analytics to provide clinical decision support in depression treatment planning. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2018, 31, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueboonthavatchai, P. Role of stress areas, stress severity, and stressful life events on the onset of depressive disorder: A case-control study. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2009, 92, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kohn, Y.; Zislin, J.; Agid, O.; Hanin, B.; Troudart, T.; Shapira, B.; Bloch, M.; Gur, E.; Ritsner, M.; Lerer, B. Increased prevalence of negative life events in subtypes of major depressive disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Kind of Stress is Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Employees? Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28378560/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Kim, Y.; Lowe, J.; Hong, O. Controlled drinking behaviors among Korean American and Korean male workers. Nurs. Res. 2021, 70, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Oh, J.W.; Lee, S. Association between drinking behaviors, sleep duration, and depressive symptoms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Nelson, C.B.; McGonagle, K.A.; Edlund, M.J.; Frank, R.G.; Leaf, P.J. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1996, 66, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, K.R.; Pinquart, M.; Gamble, S.A. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2009, 37, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Internet. Health at a Glance 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en.html (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Anthenelli, R.M. Overview: Stress and alcohol use disorders revisited. Alcohol Res. 2012, 34, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R. Alcohol use disorder and depressive disorders. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2019, 40, arcr.v40.1.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; An, Y.; Kang, U.G. ‘Drugs of Abuse’ as “new antidepressants”:—Medical and philosophical considerations in treatment. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2022, 61, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T. Strength and vulnerability integration (SAVI): A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 1068–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Giannakopoulos, P.; Herrmann, F.R.; Bartolomei, J.; Digiorgio, S.; Ortiz Chicherio, N.; Delaloye, C.; Ghisletta, P.; Lecerf, T.; de Ribaupierre, A.; et al. Stressful life events and neuroticism as predictors of late-life versus early-life depression. Psychogeriatrics 2013, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life Events, Difficulties and Onset of Depressive Episodes in Later Life. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11459383/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Baltes, P.B.; Baltes, M.M. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences; Baltes, P.B., Baltes, M.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Shin, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, M.Y.; Jung, S.; Shin, D.W.; Cho, S.J. Factors affecting depression of Korean physicians. Korean J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, K.W. A review of the epidemiology of depression in Korea. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2011, 54, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Sholomskas, D.; Pottenger, M.; Prusoff, B.A.; Locke, B.Z. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1977, 106, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Validation of the Korean Version of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (K-CESD-R). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305918445_Validation_of_the_Korean_version_of_Center_for_Epidemiologic_Studies_Depression_Scale-Revised_K-CESD-R (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Kim, Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): Current status and challenges. Epidemiol. Health 2014, 36, e2014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, M.W. A global assessment of recent stress (GARS) scale. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1985, 15, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.M.; Jang, O.J.; Choi, H.K.; Lee, Y.R. Diagnostic availability and optimal cut off score of the Korea version of alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT-K), alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) and Question 3 alone(AUDIT3) for screening of hazardous drinking. Korean Acad. Addict. Psychiatry 2017, 21, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Gulick, E.E.; Nam, K.A.; Kim, S.H. Psychometric properties of the alcohol use disorders identification test: A Korean version. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2008, 22, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Internet. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. Available online: http://afhayes.com/introduction-to-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-analysis.html (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Boden, J.M.; Fergusson, D.M. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 2011, 106, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1997, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Kang, U.G. ‘Drugs of Abuse’ as a “new antidepressant”:—A review on pharmacological mechanisms, antidepressant effects, and abuse potential. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2022, 61, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Le Moal, M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binge Drinking and Depressive Symptoms: A 5-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19438420/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanini, P. Methodological issues in assessing job stress and burnout in psychosocial research. Med. Lav. 2021, 112, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, U.; Schiel, S.; Schröder, H.; Kleudgen, M.; Tophoven, S.; Rauch, A.; Freude, G.; Müller, G. The Study on Mental Health at Work: Design and sampling. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Rhee, M.K.; Kim, M.A. Job stress, daily stress, and depressive symptoms among low-wage workers in Korea: The role of resilience. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 2019, 29, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 4959 (58.8) |

| Female | 3473 (41.2) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 37.2 ± 8.8 |

| Educational level (graduate), n (%) | |

| College graduate or lower | 1291 (15.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5613 (66.6) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 1528 (18.1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 3434 (40.7) |

| Married | 4821 (57.2) |

| Other a | 176 (2.1) |

| Working hours (weekly, hour), mean ± SD | 46.7 ± 7.7 |

| Income (monthly), n (%) | |

| Low income | 306 (3.6) |

| Middle income | 4144 (49.2) |

| High income | 3982 (47.2) |

| CES-D score, mean ± SD | 16.0 ± 9.9 |

| AUDIT-K score, mean ± SD | 8.1 ± 6.7 |

| Workplace stress, mean ± SD | 35.8 ± 30.0 |

| Family relationships, mean ± SD | 15.3 ± 22.9 |

| Interpersonal conflicts, mean ± SD | 10.0 ± 18.2 |

| Health problems, mean ± SD | 16.2 ± 21.9 |

| Financial strains, mean ± SD | 17.9 ± 23.7 |

| Traumatic events, mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 12.3 |

| Mannerisms, mean ± SD | 22.0 ± 25.5 |

| Predictor | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal conflicts | 0.039 | 0.005 | 7.498 *** | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.049 |

| Age | −0.013 | 0.013 | −1.060 | 0.289 | −0.038 | 0.011 |

| Interpersonal conflicts x age † | −0.002 | 0.001 | −3.364 ** | 0.001 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Sex (reference: male) | 0.709 | 0.175 | 4.062 *** | <0.001 | 0.367 | 1.052 |

| Educational level (reference: bachelor’s degree) | ||||||

| College graduate or lower | 0.836 | 0.236 | 3.545 *** | <0.001 | 0.374 | 1.299 |

| Master’s degree or higher | −0.449 | 0.225 | −1.995 * | 0.046 | −0.889 | −0.008 |

| Marital status (reference: single) | ||||||

| Married | −1.289 | 0.217 | −5.950 *** | <0.001 | −1.714 | −0.864 |

| Other a | 0.968 | 0.610 | 1.585 | 0.113 | −0.229 | 2.164 |

| Working hours (weekly, hour) | 0.036 | 0.011 | 3.273 ** | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.058 |

| Income (reference: middle income) | ||||||

| Low income | 1.132 | 0.449 | 2.521 * | 0.012 | 0.252 | 2.013 |

| High income | −0.773 | 0.188 | −4.099 *** | <0.001 | −1.142 | −0.403 |

| Life stressors (covariates): | ||||||

| Workplace stress | 0.134 | 0.003 | 42.741 *** | <0.001 | 0.128 | 0.140 |

| Family relationships | 0.054 | 0.004 | 13.363 *** | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.062 |

| Health problems | 0.022 | 0.004 | 5.083 *** | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.030 |

| Financial strains | 0.017 | 0.004 | 4.304 *** | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.025 |

| Traumatic events | 0.026 | 0.007 | 3.733 *** | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.039 |

| Mannerisms | 0.074 | 0.004 | 20.536 *** | <0.001 | 0.067 | 0.081 |

| F = 374.117 ***, R2 = 0.430, R2 change = 0.001 ** | ||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traumatic events | 0.024 | 0.007 | 3.495 *** | <0.001 | 0.011 | 0.037 |

| Alcohol use | 0.079 | 0.013 | 6.134 *** | <0.001 | 0.054 | 0.105 |

| Traumatic events x alcohol use ‡ | 0.003 | 0.001 | 3.444 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Sex (reference: male) | 1.018 | 0.180 | 5.640 *** | <0.001 | 0.664 | 1.371 |

| Age | −0.006 | 0.013 | −0.454 | 0.650 | −0.030 | 0.019 |

| Educational level (reference: bachelor’s degree) | ||||||

| College graduate or lower | 0.842 | 0.235 | 3.575 *** | <0.001 | 0.380 | 1.303 |

| Master’s degree or higher | −0.378 | 0.225 | −1.685 | 0.092 | −0.819 | 0.062 |

| Marital status (reference: single) | ||||||

| Married | −1.258 | 0.216 | −5.815 *** | <0.001 | −1.682 | −0.834 |

| Other a | 0.856 | 0.608 | 1.408 | 0.159 | −0.336 | 2.047 |

| Working hours (weekly, hour) | 0.035 | 0.011 | 3.162 ** | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.056 |

| Income (reference: middle income) | ||||||

| Low income | 1.172 | 0.448 | 2.616 ** | 0.009 | 0.294 | 2.051 |

| High income | −0.864 | 0.189 | −4.582 *** | <0.001 | −1.234 | −0.494 |

| Life stressors (covariates): | ||||||

| Workplace stress | 0.133 | 0.003 | 42.541 | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.139 |

| Family relationships | 0.054 | 0.004 | 13.235 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.062 |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 0.040 | 0.005 | 7.963 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 0.050 |

| Health problems | 0.021 | 0.004 | 5.042 | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.030 |

| Financial strains | 0.016 | 0.004 | 3.891 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.023 |

| Mannerisms | 0.074 | 0.004 | 20.352 | <0.001 | 0.066 | 0.081 |

| F = 357.212 ***, R2 = 0.433, R2 change = 0.001 ** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, J.; Jeon, S.-W.; An, Y.; Cho, S.J. Life Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Roles of Alcohol Consumption and Age. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101126

Moon J, Jeon S-W, An Y, Cho SJ. Life Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Roles of Alcohol Consumption and Age. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101126

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Jiwan, Sang-Won Jeon, Yoosuk An, and Sung Joon Cho. 2025. "Life Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Roles of Alcohol Consumption and Age" Brain Sciences 15, no. 10: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101126

APA StyleMoon, J., Jeon, S.-W., An, Y., & Cho, S. J. (2025). Life Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Roles of Alcohol Consumption and Age. Brain Sciences, 15(10), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101126