Relationships Among Bullying Experiences, Mood Symptoms and Suicidality in Subjects with and Without Autism Spectrum Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Procedures

- -

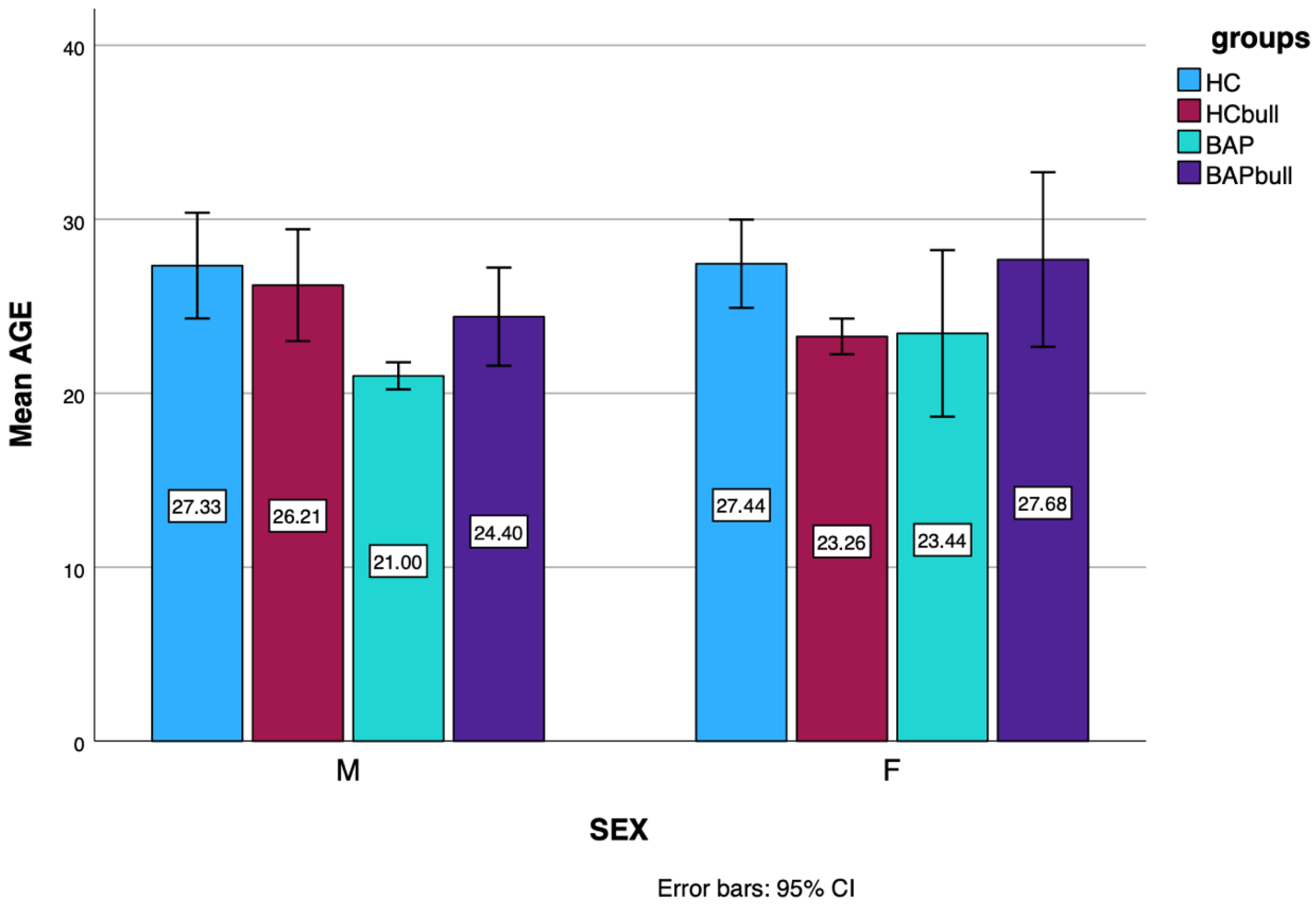

- 39 BAP individuals who did not experience bullying (F:16; M:23; mean age: 25.46 ± 9.40);

- -

- 59 BAP individuals who experienced bullying (Bullied BAP) (F:19; M:40; mean age: 22.00 ± 5.93);

- -

- 112 HCs who experienced bullying (Bullied HCs) (F:27; M:19; mean age: 27.35 ± 10.22);

- -

- and 46 HCs who did not experience bullying (F:70; M:42; mean age: 24.48 ± 4.99) (see Figure 1).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Adult Autism Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum)

2.2.2. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

2.2.3. The MOOD Spectrum—Self Report (MOODS-SR)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| BAP | Broad Autism Phenotype |

| HCs | Healthy Controls |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders |

| AOUP | Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana |

| AdAS Spectrum | Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum |

| AQ | Autism Spectrum Quotient |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| MOOD-SR | Mood Spectrum—Self Report |

References

- Waseem, M.; Nickerson, A.B. Identifying and Addressing Bullying. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lancet Psychiatry. Why be happy when you could be normal? Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Bully/victim problems among school children: Some basic facts and effects of a school-based intervention program. In The Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression; Psychology Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 411–448. [Google Scholar]

- Ariani, T.A.; Putri, A.R.; Firdausi, F.A.; Aini, N. Global prevalence and psychological impact of bullying among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 385, 119446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, R. Bullying in children: Impact on child health. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e000939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyuboglu, M.; Eyuboglu, D.; Pala, S.C.; Oktar, D.; Demirtas, Z.; Arslantas, D.; Unsal, A. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D.S.; Boulton, M.J. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22 (Suppl. 1), 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, E.; Garmy, P.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, G. Bullying, health complaints, and self-rated health among school-aged children and adolescents. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519895355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Låftman, S.B.; Alm, S.; Sandahl, J.; Modin, B. Future Orientation among Students Exposed to School Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F.; Loeber, R. Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2011, 3, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Rimpelä, M.; Rantanen, P.; Rimpelä, A. Bullying at school--an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, S.; Brunstein Klomek, A.; Apter, A.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Hoven, C.W.; Sarchiapone, M.; Balazs, J.; Kereszteny, A.; et al. Bullying Victimization and Suicide Ideation and Behavior Among Adolescents in Europe: A 10-Country Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E.; Wolke, D.; Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Lorenzi, P.; Carpita, B. The neurodevelopmental continuum towards a neurodevelopmental gradient hypothesis. J. Psychopathol. 2019, 25, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Carpita, B.; Carmassi, C.; Calderoni, S.; Muti, D.; Muscarella, A.; Massimetti, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Gesi, C.; Conti, E.; Muratori, F.; et al. The broad autism phenotype in real-life: Clinical and functional correlates of autism spectrum symptoms and rumination among parents of patients with autism spectrum disorder. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, J.A.; Fardella, M.A. Victimization and Perpetration Experiences of Adults with Autism. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Lavoie, S.M.; Viecili, M.A.; Weiss, J.A. Sexual knowledge and victimization in adults with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandell, D.S.; Walrath, C.M.; Manteuffel, B.; Sgro, G.; Pinto-Martin, J.A. The prevalence and correlates of abuse among children with autism served in comprehensive community-based mental health settings. Child Abus. Negl. 2005, 29, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actis-Grosso, R.; Bossi, F.; Ricciardelli, P. Emotion recognition through static faces and moving bodies: A comparison between typically developed adults and individuals with high level of autistic traits. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanyon, D.; Yamasaki, S.; Ando, S.; Endo, K.; Nakanishi, M.; Kiyono, T.; Hosozawa, M.; Kanata, S.; Fujikawa, S.; Morimoto, Y.; et al. The role of bullying victimization in the pathway between autistic traits and psychotic experiences in adolescence: Data from the Tokyo Teen Cohort study. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 239, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.M.; Knutson, J.F. Maltreatment and disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study. Child Abus. Negl. 2000, 24, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, Y.; Koh, Y.-J.; Leventhal, B. Autism Spectrum Disorder and school bullying: Who is the victim? Who is the perpetrator? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maïano, C.; Normand, D.; Salvas, M.-C.; Moullec, G.; Aimé, A. Prevalence of school bullying among youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.H.; Cappadocia, M.C.; Bebko, J.M.; Pepler, D.J.; Weiss, J.A. Shedding light on a pervasive problem: A review of research on bullying experiences among children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1520–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappadocia, M.C.; Weiss, J.A.; Pepler, D. Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhill, G.P. Outcomes in adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2007, 22, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P. Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism 2000, 4, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happe, F.G.E. An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1994, 24, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, T.; Baron-Cohen, S. A test of central coherence theory: Linguistic processing in high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome: Is local coherence impaired? Cognition 1999, 71, 149–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Gesi, C.; Massimetti, E.; Cremone, I.M.; Barbuti, M.; Maccariello, G.; Moroni, I.; Barlati, S.; Castellini, G.; Luciano, M.; et al. Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum): Validation of a questionnaire investigating subthreshold autism spectrum. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 73, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Skinner, R.; Martin, J.; Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Armani, A.; Rucci, P.; Frank, E.; Fagiolini, A.; Corretti, G.; Shear, M.K.; Grochocinski, V.J.; Maser, J.D.; En-dicott, J.; et al. Measuring moodspectrum disorder: Comparison of interview (SCI-MOODS) and self-report (MOODS-SR) instruments. Compr. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Cremone, I.M.; Chiarantini, I.; Nardi, B.; Pronestì, C.; Amatori, G.; Massimetti, E.; Signorelli, M.S.; Rocchetti, M.; Castellini, G.; et al. Autistic traits are associated with the presence of post-traumatic stress symptoms and suicidality among subjects with Autism spectrum conditions and Anorexia nervosa. J. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 181, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremone, I.M.; Nardi, B.; Amatori, G.; Palego, L.; Baroni, D.; Casagrande, D.; Massimetti, E.; Betti, L.; Giannaccini, G.; Dell’Osso, L.; et al. Unlocking the Secrets: Exploring the Biochemical Correlates of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Nardi, B.; Bonelli, C.; Gravina, D.; Benedetti, F.; Amatori, G.; Battaglini, S.; Massimetti, G.; Luciano, M.; Be-rardelli, I.; et al. Investigating suicidality across the autistic-catatonic continuum in a clinical sample of subjects with major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1124241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, S.; Milrod, B.; Nardi, B.; Massimetti, G.; Bonelli, C.; Baldwin, D.S.; Domschke, K.; Schiele, M.; Dell’Osso, L.; Carpita, B. Relationship between anhedonia, separation anxiety, attachment style and suicidality in a large cohort of individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 379, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremone, I.M.; Dell’Osso, L.; Nardi, B.; Giovannoni, F.; Parri, F.; Pronestì, C.; Bonelli, C.; Massimetti, G.; Pini, S.; Carpita, B. Altered Rhythmicity, Depressive Ruminative Thinking and Suicidal Ideation as Possible Correlates of an Unrecognized Autism Spectrum in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Hidalgo, P.; Voltas, N.; Canals, J. Self-perceived bullying victimization in pre-adolescents on the autism spectrum: EPINED study. Autism 2024, 28, 2848–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Amatori, G.; Bonelli, C.; Nardi, B.; Massimetti, E.; Cremone, I.M.; Carpita, B. Autistic traits underlying social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and panic disorders. CNS Spectr. 2024, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Nardi, B.; Bonelli, C.; Amatori, G.; Pereyra, M.A.; Massimetti, E.; Cremone, I.M.; Pini, S.; Carpita, B. Autistic Traits as Predictors of Increased Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Severity: The Role of Inflexibility and Communication Impairment. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, B.; Bonelli, C.; Schifanella, V.; Nardi, B.; Amatori, G.; Massimetti, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Pini, S.; Dell’Osso, L. Autistic traits as predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms among patients with borderline personality disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1443365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, C.; Nemeroff, C.B. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Gunnar, M.; Cicchetti, D. Altered neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children related to symptoms of depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996, 8, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Gunnar, M.; Cicchetti, D. Salivary cortisol in maltreated children: Evidence of relations between neuroendocrine activity and social competence. Dev. Psychopathol. 1995, 7, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Nemeroff, C.B. The impact of early adverse experiences on brain systems involved in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachtel, L.; Commins, E.; Park, M.; Rolider, N.; Stephens, R.; Reti, I. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and delirious mania as malignant catatonia in autism: Prompt relief with electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015, 132, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbin, D.; Gutwinski, S.; Schreiter, S.; Heinz, A. Perspectives in poverty and mental health. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 975482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, G.; Lambourg, E.; Steele, J.D.; Colvin, L.A. The effect of adverse childhood experiences on chronic pain and major depression in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijenvanger, E.J.; Pollok, T.M.; Monninger, M.; Kaiser, A.; Brandeis, D.; Banaschewski, T.; Holz, N.E. Impact of early life adversities on human brain functioning: A coordinate-based meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 113, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMoult, J.; Humphreys, K.L.; Tracy, A.; Hoffmeister, J.A.; Ip, E.; Gotlib, I.H. Meta-analysis: Exposure to Early Life Stress and Risk for Depression in Childhood and Adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, G. Peer victimization and diurnal cortisol rhythm among children affected by parental HIV: Mediating effects of emotional regulation and gender differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, T.; Hymel, S.; McDougall, P. The biological underpinnings of peer victimization: Understanding why and how the effects of bullying can last a lifetime. Theory Pract. 2013, 52, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Stellar, E. Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993, 153, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, W. Violence exposure and cortisol responses in urban youth. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 13, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, J.M.; Jensen-Campbell, L.A.; Baum, A. ì Worse than sticks and stones? Bullying is associated with altered HPA axis functioning and poorer health. Brain Cogn. 2011, 77, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, C.D.; Helms, S.W.; Heilbron, N.; Rudolph, K.D.; Hastings, P.D.; Prinstein, M.J. Relational victimization, friendship, and adolescents’ hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis responses to an in vivo social stressor. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliewer, W. Victimization and biological stress responses in urban adolescents: Emotion regulation as a moderator. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouellet-Morin, I.; Odgers, C.L.; Danese, A.; Bowes, L.; Shakoor, S.; Papadopoulos, A.S.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Blunted cortisol responses to stress signal social and behavioral problems among maltreated/bullied 12-year-old children. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouellet-Morin, I.; Danese, A.; Bowes, L.; Shakoor, S.; Ambler, A.; Pariante, C.M.; Papadopoulos, A.S.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. A discordant monozygotic twin design shows blunted cortisol reactivity among bullied children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Zhou, E.S. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A.; Charman, T.; Chandler, S.; Loucas, T.; Baird, G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Wozniak, J.; Petty, C.; Martelon, M.K.; Fried, R.; Bolfek, A.; Kotte, A.; Stevens, J.; Furtak, S.L.; Bourgeois, M.; et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and functioning in a clinically referred population of adults with autism spectrum disorders: A comparative study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollocks, M.J.; Lerh, J.W.; Magiati, I.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Brugha, T.S. Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlot, L.; Deutsch, C.K.; Albert, A.; Hunt, A.; Connor, D.F.; McIlvane, W.J.J. Mood and anxiety symptoms in psychiatric inpatients with autism spectrum disorder and depression. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2008, 1, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazefsky, C.A.; Folstein, S.E.; Lainhart, J.E. Overrepresentation of mood and anxiety disorders in adults with autism and their first-degree relatives: What does it mean? Autism Res. 2008, 1, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, T.R.; Viskochil, J.; Farley, M.; Coon, H.; McMahon, W.M.; Morgan, J.; Bilder, D.A. Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.; Unruh, K.; Lord, C. Depression and its measurement in verbal adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2015, 19, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Wittchen, H.U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, B.; Nardi, B.; Bonelli, C.; Massimetti, E.; Amatori, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Pini, S.; Dell’Osso, L. Presence and correlates of autistic traits among patients with social anxiety disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1320558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, B.; Nardi, B.; Tognini, V.; Poli, F.; Amatori, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Pini, S.; Dell’Osso, L. Autistic Traits and Somatic Symptom Disorders: What Is the Link? Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, D.S.; Guyer, A.E.; Goldwin, M.; Towbin, K.A.; Leibenluft, E. Autism spectrum disorder scale scores in pediatric mood and anxiety disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunihira, Y.; Senju, A.; Dairoku, H.; Wakabayashi, A.; Hasegawa, T. ‘Autistic’traits in non-autistic Japanese populations: Relationships with personality traits and cognitive ability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunalska, A.; Rzeszutek, M.; Dębowska, Z.; Bryńska, A. Comorbidity of bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorder—Review paper. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.S.; Sharma, M.; Chatterjee, K.; Prakash, J.; Srivastava, K.; Chaudhury, S. Childhood trauma and bipolar affective disorder: Is there a linkage? Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32 (Suppl. 1), S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquerizo-Serrano, J.; Salazar De Pablo, G.; Singh, J.; Santosh, P. Catatonia in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 65, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Amatori, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Massimetti, E.; Nardi, B.; Gravina, D.; Benedetti, F.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Pompili, M.; Politi, P.; et al. Autistic and Catatonic Spectrum Symptoms in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Amatori, G.; Carpita, B.; Massimetti, G.; Nardi, B.; Gravina, D.; Benedetti, F.; Bonelli, C.; Casagrande, D.; Luciano, M.; et al. The mediating effect of mood spectrum on the relationship between autistic traits and catatonia spectrum. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1092193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, E. Shell shock. J. R. Army Med. Corps 2014, 160 (Suppl. 1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biles, T.R.; Anem, G.; Youssef, N.A. Should Catatonia Be Conceptualized as a Pathological Response to Trauma? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, N.A.; Hernandez, J.; Biles, T. Can catatonia be a pathological response to fear and trauma? Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, P.L.H.; Pickles, A.; Durkin, K.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Longitudinal trajectories of peer relations in children with specific language impairment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014, 55, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureda-Garcia, I.; Valera-Pozo, M.; Sanchez-Azanza, V.; Adrover-Roig, D.; Aguilar-Mediavilla, E. Associations Between Self, Peer, and Teacher Reports of Victimization and Social Skills in School in Children with Language Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, C.L.; Gibson, J.L.; St Clair, M.C. Social functioning as a mediator between developmental language disorder (DLD) and emotional problems in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Rodríguez, A.; Ahufinger, N.; Ferinu, L.; García-Arch, J.; Andreu, L.; Sanz-Torrent, M. Dificultades sociales, emocionales y victimización específica por el lenguaje en el trastorno del desarrollo del lenguaje. Rev. Logop. Foniatría Audiol. 2021, 41, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N.; Mullins, P.M. Self-concept and self-esteem in developmental dyslexia. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2004, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S.M. Peer victimization among students with specific language impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and typical development. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2011, 42, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjas, M.I.; Martín-Antón, L.J.; García-Bacete, F.-J.; Sanchiz, M.L. Rejection and victimization of students with special educational needs in first grade of primary education. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 499–511. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, E.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Bullying risks of 11-year-old children with specific language impairment (SLI): Does school placement matter? Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2003, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Bullying in young people with a history of specific language impairment (SLI). Educ. Child Psychol. 2007, 24, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, G.; Bates, G.; Feuerstein, M.; Mason-Apps, E.; White, C. Peer acceptance of children with language and communication impairments in a mainstream primary school: Associations with type of language difficulty, problem behaviours and a change in placement organization. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2012, 28, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Ramsden, G.; Botting, N. Social difficulties and victimization in children with SLI at 11 years of age. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2004, 47, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, B.; Loth, E.; Murphy, D.G. Autism and mood disorders. Int. Rev. Ppsychiatry 2021, 33, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Cremone, I.M.; Nardi, B.; Tognini, V.; Castellani, L.; Perrone, P.; Amatori, G.; Carpita, B. Comorbidity and Overlaps between Autism Spectrum and Borderline Personality Disorder: State of the Art. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.L.; Koenen, K.C.; Lyall, K.; Robinson, E.B.; Weisskopf, M.G. Association of autistic traits in adulthood with childhood abuse, interpersonal victimization, and posttraumatic stress. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 45, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Amatori, G.; Giovannoni, F.; Massimetti, E.; Cremone, I.M.; Carpita, B. Rumination and altered reactivity to sensory input as vulnerability factors for developing post-traumatic stress symptoms among adults with autistic traits. CNS Spectr. 2024, 29, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, G.; Kenny, R.; Griffiths, S.; Allison, C.; Mosse, D.; Holt, R.; O’Connor, R.C.; Cassidy, S.; Baron-Cohen, S. Autistic traits in adults who have attempted suicide. Mol. Autism 2019, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.; Chihuri, S.; DiGuiseppi, C.G.; Li, G. Risk of Self-Harm in Children and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2021, 4, e2130272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husky, M.M.; Bitfoi, A.; Carta, M.G.; Goelitz, D.; Koç, C.; Lesinskiene, S.; Mihova, Z.; Otten, R.; Kovess-Masfety, V. Bullying involvement and suicidal ideation in elementary school children across Europe. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Hong, Q.; Li, L.; Xie, X.; Chen, W.; Shen, W.; Liu, H.; Hu, Z. The mediating effects of school bullying victimization in the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI among adolescents with mood disorders. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S.; Bradley, P.; Robinson, J.; Allison, C.; McHugh, M.; Baron-Cohen, S. Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: A clinical cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvikoski, T.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Boman, M.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Bölte, S. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette-Smith, M.; Weiss, J.; Lunsky, Y. History of suicide attempts in adults with Asperger syndrome. Crisis 2014, 35, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelton, M.K.; Cassidy, S.A. Are autistic traits associated with suicidality? A test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide in a non-clinical young adult sample. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takara, K.; Kondo, T. Comorbid atypical autistic traits as a potential risk factor for suicide attempts among adult depressed patients: A case-control study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2014, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S.; Bradley, L.; Shaw, R.; Baron-Cohen, S. Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, S.; Allison, C.; Kenny, R.; Holt, R.; Smith, P.; Baron-Cohen, S. The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.L.; Dritschel, B. Modeling the impact of social problem-solving deficits on depressive vulnerability in the broader autism phenotype. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2016, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L.; Heisel, M.J. The destructiveness of perfectionism revisited: Implications for the assessment of suicide risk and the prevention of suicide. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezo, J.; Paris, J.; Turecki, G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 113, 180–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, B.; Heron, J.; Klonsky, E.D.; Moran, P.; O’Connor, R.C.; Tilling, K.; Wilkinson, P.; Gunnell, D. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: A birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, D.; Uljarević, M.; Foley, K.-R.; Richdale, A.; Trollor, J. Risk and protective factors underlying depression and suicidal ideation in autism spectrum disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, L.E.; Williams White, S. Loneliness, social relationships, and a broader autism phenotype in college students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosbrook, A.; Whittingham, K. Autistic traits in the general population: What mediates the link with depressive and anxious symptomatology? Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010, 4, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Pan, T.-L.; Lan, W.-H.; Hsu, J.-W.; Huang, K.-L.; Su, T.-P.; Li, C.T.; Lin, W.C.; Wei, H.T.; Chen, T.J.; et al. Risk of suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide longitudinal follow-up study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, e1174–e1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseneault, L.; Walsh, E.; Trzesniewski, K.; Newcombe, R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. Bullying victimization uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young children: A nationally representative cohort study. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomek, A.B.; Sourander, A.; Niemelä, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; Piha, J.; Tamminen, T.; Almqvist, F.; Gould, M.S. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: A population-based birth cohort study. J. Am. Acad Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løhre, A.; Lydersen, S.; Paulsen, B.; Mæhle, M.; Vatten, L.J. Peer victimization as reported by children, teachers, and parents in relation to children’s health symptoms. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwierzynska, K.; Wolke, D.; Lereya, T.S. Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: A prospective longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Leventhal, B. Bullying and suicide. A review. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M.; Vedder, P.; Tanilon, J. Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.K.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M.; Polanin, J.R.; Holland, K.M.; DeGue, S.; Matjasko, J.L.; Wolfe, M.; Reid, G. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e496–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Chen, S.; Saklofske, D.H.; Mushquash, C.; Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. The perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic review of the perfectionism-suicide relationship. J. Pers. 2018, 86, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, L.M.; Forkmann, T.; Teismann, T. Suicide-specific rumination as a predictor of suicide planning and intent. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 180, 104597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B.; Leach, E.; Dinsdale, N.; Mokkonen, M.; Hurd, P. Imagination in human social cognition, autism, and psychotic-affective conditions. Cognition 2016, 150, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Huang, X.; Fox, K.R.; Franklin, J.C. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, J.; Hicks, E.T.; Mack, S.A.; Levin, M.E. Psychological Inflexibility Predicts Suicidality Over Time in College Students. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BAP (Mean ± SD) | Bullied BAP (Mean ± SD) | HC (Mean ± SD) | Bullied HC (Mean ± SD) | F | p | H2 | C.I. 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

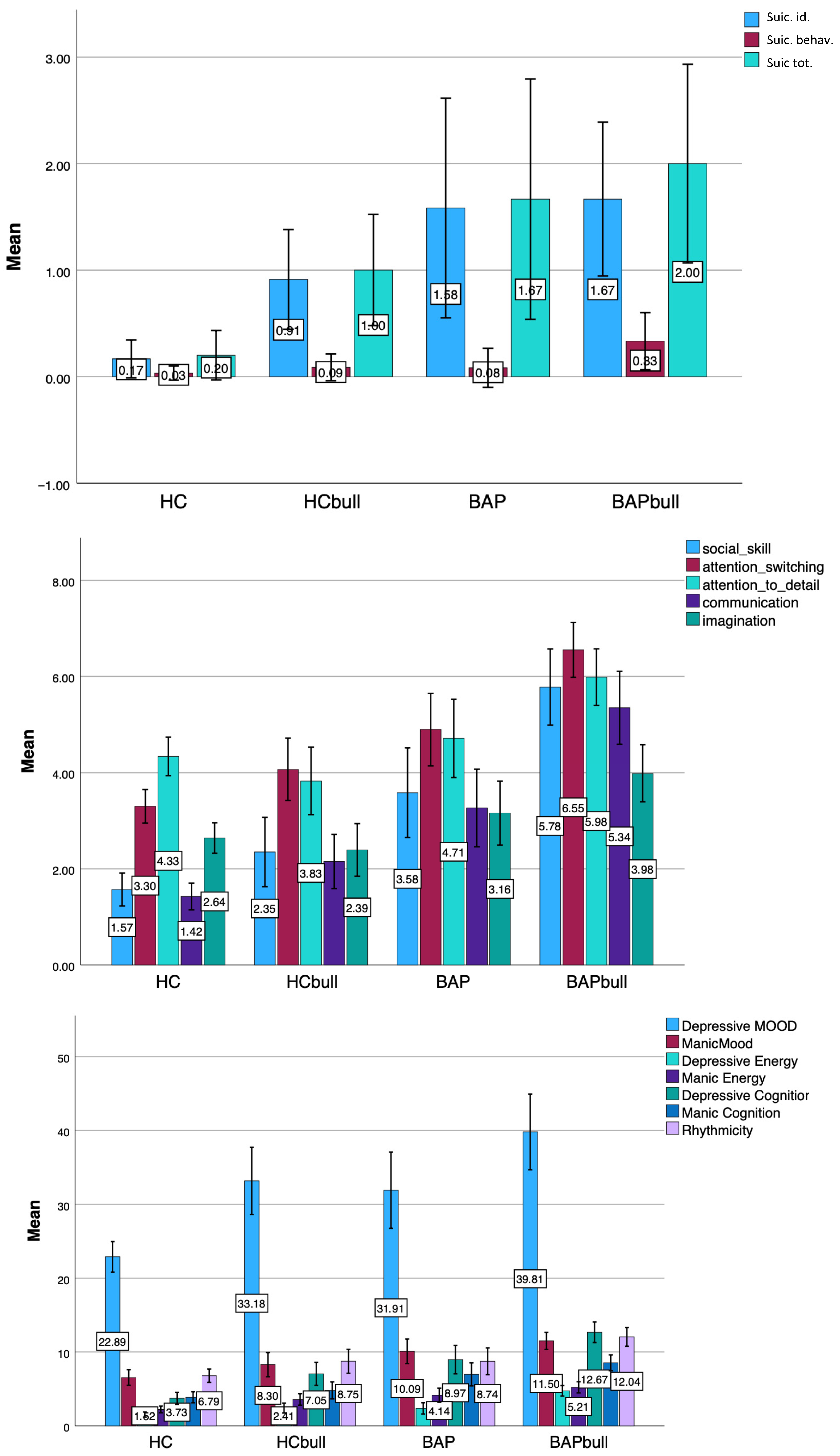

| MOOD-SR Suicidality | |||||||||

| Suic. id. | 1.37 ± 1.59 | 1.93 ± 1.65 | 0.22 ± 0.77 | 0.81 ± 1.17 | 17.396 | <0.001 * | 0.257 | 0.135 | 0.354 |

| Suic. behav. | 0.08 ± 0.29 | 0.32 ± 0.63 | 0.03 ± 0.26 | 0.12 ± 0.34 | 3.435 | 0.019 ° | 0.080 | 0.002 | 0.168 |

| Suic. tot. | 1.67 ± 1.77 | 2.00 ± 2.21 | 0.20 ± 0.90 | 1.00 ± 1.21 | 11.111 | <0.001 ^ | 0.225 | 0.090 | 0.333 |

| AQ | |||||||||

| Social Skill | 3.61 ± 2.81 | 5.71 ± 3.03 | 1.55 ± 1.80 | 2.35 ± 2.43 | 40.367 | <0.001 # | 0.325 | 0.229 | 0.401 |

| Att. Switc. | 4.87 ± 2.26 | 6.58 ± 2.16 | 3.25 ± 1.88 | 4.06 ± 2.17 | 34.810 | <0.001 # | 0.291 | 0.197 | 0.369 |

| Att. detail | 4.74 ± 2.45 | 6.02 ± 2.24 | 4.31 ± 2.11 | 3.83 ± 2.36 | 10.324 | <0.001 § | 0.109 | 0.041 | 0.176 |

| Comm. | 3.26 ± 2.46 | 5.30 ± 2.88 | 1.39 ± 1.47 | 2.15 ± 1.90 | 47.097 | <0.001 # | 0.358 | 0.263 | 0.433 |

| Imagin. | 3.15 ± 1.99 | 3.98 ± 2.24 | 2.61 ± 1.69 | 2.39 ± 1.84 | 8.383 | <0.001 ¥ | 0.091 | 0.028 | 0.155 |

| AQ tot. | 19.60 ± 8.94 | 27.64 ± 9.73 | 13.26 ± 5.11 | 14.78 ± 7.26 | 49.805 | <0.001 £ | 0.375 | 0.279 | 0.450 |

| MOOD-SR | |||||||||

| Dep. Mood | 31.91 ± 15.04 | 39.81 ± 17.65 | 22.89 ± 11.08 | 33.18 ± 14.96 | 18.648 | <0.001 $ | 0.192 | 0.103 | 0.270 |

| Man. Mood | 10.09 ± 4.88 | 11.50 ± 4.01 | 6.54 ± 5.63 | 8.30 ± 5.40 | 11.753 | <0.001 * | 0.130 | 0.054 | 0.203 |

| Dep. En. | 2.37 ± 2.21 | 4.75 ± 2.41 | 1.52 ± 1.83 | 2.41 ± 2.22 | 26.845 | <0.001 # | 0.254 | 0.158 | 0.335 |

| Man. En. | 4.14 ± 2.79 | 5.21 ± 2.61 | 2.22 ± 2.44 | 3.57 ± 2.54 | 17.204 | <0.001 $ | 0.179 | 0.092 | 0.257 |

| Dep. Cogn. | 8.97 ± 5.62 | 12.67 ± 4.78 | 3.73 ± 4.38 | 7.05 ± 5.15 | 41.644 | <0.001 & | 0.346 | 0.247 | 0.424 |

| Man. Cogn. | 6.97 ± 4.53 | 8.54 ± 3.70 | 3.87 ± 4.01 | 4.80 ± 3.79 | 17.612 | <0.001 * | 0.183 | 0.095 | 0.261 |

| Rhythm. | 8.74 ± 5.31 | 12.04 ± 4.37 | 6.79 ± 4.84 | 8.75 ± 5.33 | 12.935 | <0.001 § | 0.141 | 0.062 | 0.216 |

| MOOD-SR tot. | 70.37 ± 29.35 | 94.45 ± 26.60 | 47.57 ± 26.10 | 68.05 ± 28.69 | 35.244 | <0.001 † | 0.313 | 0.214 | 0.392 |

| Social Skill | Att. Switch. | Att. to Detail | Comm. | Imag. | AQ tot. Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Mood | 0.585 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.355 ** | 0.609 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Manic Mood | 0.072 | 0.179 | 0.134 | 0.101 | −0.047 | 0.112 |

| c | 0.493 | 0.089 | 0.203 | 0.338 | 0.661 | 0.293 |

| Dep. Energy | 0.450 ** | 0.475 * | 0.198 | 0.375 ** | 0.263 * | 0.454 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Manic Energy | 0.146 | 0.333 ** | 0.186 | 0.270 ** | 0.090 | 0.259 * |

| p | 0.164 | 0.001 | 0.075 | 0.009 | 0.397 | 0.013 |

| Dep. Cognition | 0.486 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.538 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Manic Cognition | 0.128 | 0.339 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.253 * | 0.124 | 0.281 ** |

| p | 0.223 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.242 | 0.007 |

| Rhythmicity | 0.254 * | 0.402 ** | 0.210 * | 0.303 ** | 0.187 | 0.343 * |

| p | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.075 | 0.001 |

| MOOD-SR tot. score | 0.531 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.526 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.606 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.327 ** | 0.249 | 0.372 ** | 0.210 | 0.204 | 0.337 ** |

| p | 0.010 | 0.051 | 0.003 | 0.101 | 0.115 | 0.008 |

| Suicidal behav. | 0.357 * | 0.262 | 0.298 * | 0.261 | 0.343 * | 0.373 * |

| p | 0.012 | 0.069 | 0.038 | 0.071 | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| Suicidality total | 0.355 * | 0.185 | 0.323 * | 0.249 | 0.195 | 0.327 * |

| p | 0.014 | 0.212 | 0.027 | 0.091 | 0.189 | 0.025 |

| B (S.E.) | Beta | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| constant | −0.246 (0.284) | −0.869 | 0.387 | |

| AQ total score | 0.047 (0.015) | 0.286 | 3.131 | 0.02 |

| Bullied | 0.718 (0.293) | 0.224 | 2.450 | 0.16 |

| B (S.E.) | Beta | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| constant | −0.182 (0.207) | −0.878 | 0.381 | |

| AQ total score | 0.041 (0.011) | 0.299 | 3.736 | <0.001 |

| Bullied | 0.604 (0.218) | 0.222 | 2.775 | 0.006 |

| B (S.E.) | Beta | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| constant | −0.149 (0.71) | −2.084 | 0.039 | |

| AQ total score | 0.013 (0.004) | 0.312 | 3.383 | 0.001 |

| Bullied | 0.092 (0.073) | 0.116 | 1.254 | 0.212 |

| BAP1 | Bullied BAP1 | t | p | Cohen’s d | C.I. 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| MOOD-SR Suicidality | |||||||

| Suic. id. | 1.54 ± 1.66 | 1.87 ± 1.67 | −0.541 | 0.593 | 1.666 | −0.934 | 0.534 |

| Suic. behave. | 0.11 ± 0.33 | 0.08 ± 0.28 | 0.262 | 0.796 | 0.031 | −0.738 | 0.963 |

| Suic. tot. | 2.00 ± 1.87 | 1.50 ± 1.83 | 0.613 | 0.547 | 1.850 | −0.602 | 1.135 |

| AQ | |||||||

| Social Skill | 3.12 ± 2.61 | 4.09 ± 2.80 | −1.432 | 0.157 | 2.707 | −0.851 | 0.138 |

| Att. Switch. | 4.34 ± 1.93 | 5.19 ± 1.51 | −1.948 | 0.056 | 1.732 | −0.983 | 0.012 |

| Att. detail | 4.31 ± 2.29 | 5.37 ± 2.27 | −1.864 | 0.067 | 2.280 | −0.961 | 0.033 |

| Comm. | 2.48 ± 1.73 | 3.50 ± 2.11 | −2.087 | 0.041 * | 1.932 | −1.026 | −0.021 |

| Imagin. | 2.81 ± 1.65 | 2.71 ± 1.59 | 0.251 | 0.803 | 1.626 | −0.431 | 0.557 |

| AQ tot. | 16.98 ± 6.26 | 20.77 ± 6.51 | −2.345 | 0.022 * | 6.390 | −1.102 | −0.084 |

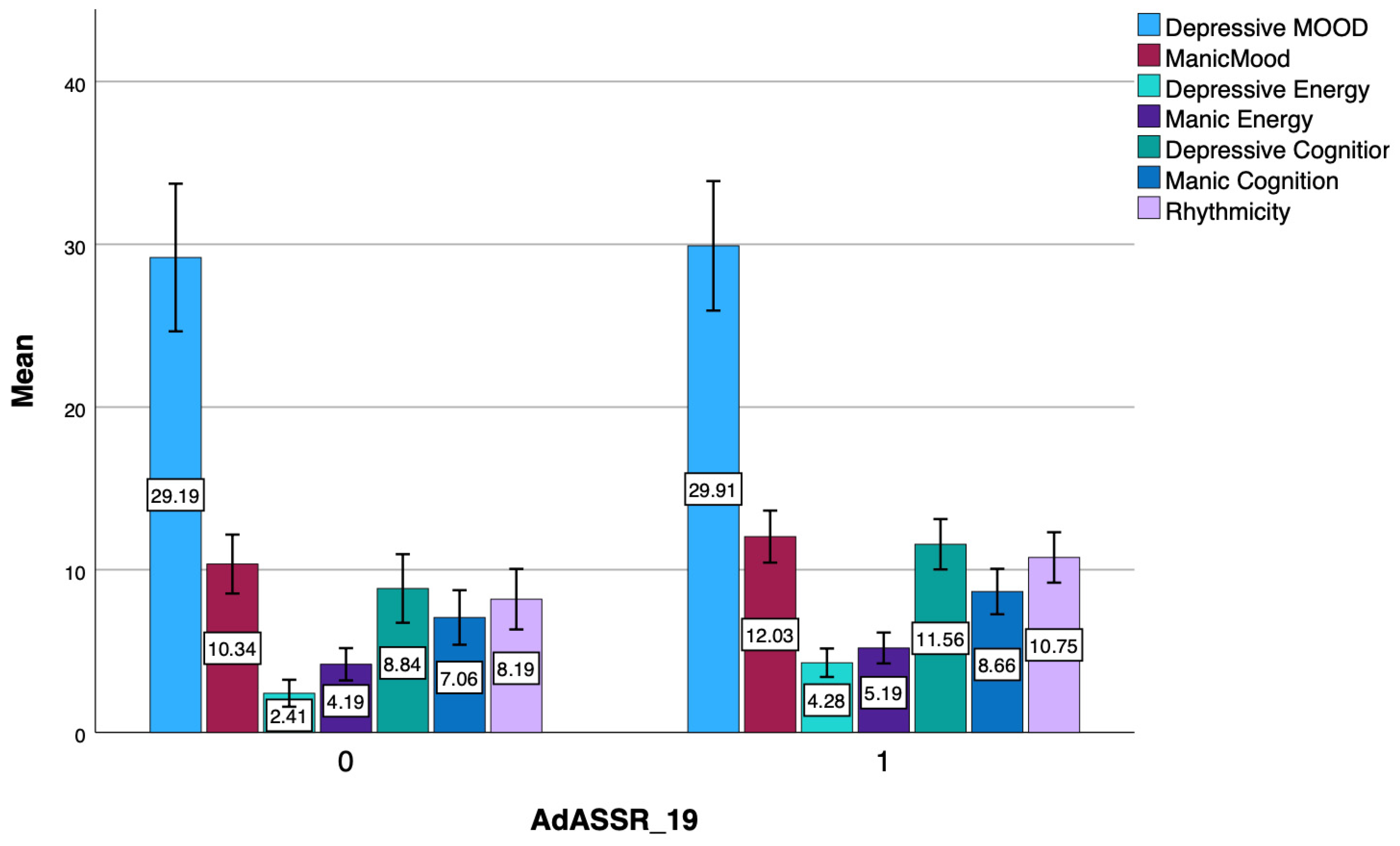

| MOOD-SR | |||||||

| Dep. Mood | 29.19 ± 12.58 | 29.91 ± 11.04 | −0.243 | 0.809 | 11.836 | −0.551 | 0.430 |

| Man. Mood | 10.34 ± 5.02 | 12.03 ± 4.43 | −1.425 | 0.159 | 4.735 | −0.849 | 0.139 |

| Dep. Energy | 2.41 ± 2.30 | 4.28 ± 2.43 | −3.174 | 0.002 * | 2.363 | −1.300 | −0.281 |

| Man. Energy | 4.19 ± 2.75 | 5.19 ± 2.63 | −1.485 | 0.143 | 2.693 | −0.864 | 0.124 |

| Dep. Cogn. | 8.84 ± 5.84 | 11.56 ± 4.29 | −2.122 | 0.038 * | 5.124 | −1.027 | −0.030 |

| Man. Cogn. | 7.06 ± 4.65 | 8.66 ± 3.87 | −1.490 | 0.141 | 4.279 | −0.865 | 0.123 |

| Rhythm. | 8.19 ± 5.16 | 10.75 ± 4.30 | −2.159 | 0.035 * | 4.747 | −1.037 | −0.039 |

| MOOD-SR tot. | 70.22 ± 27.78 | 82.38 ± 20.81 | −1.982 | 0.052 | 24.536 | −0.991 | 0.004 |

| ASD | Bullied ASD | t | p | Cohen’s d | C.I. 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| MOOD-SR Suicidality | |||||||

| Suic. id. | 0.67 ± 1.15 | 2.00 ± 1.69 | −1.291 | 0.215 | 1.633 | −2.075 | 0.467 |

| Suic. behave. | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.58 ± 0.79 | −2.548 | 0.027 * | 0.729 | −2.087 | 0.516 |

| Suic. tot. | 0.67 ± 1.15 | 2.50 ± 2.50 | −1.864 | 0.101 | 2.348 | −2.066 | 0.533 |

| AQ | |||||||

| Social Skill | 5.86 ± 2.73 | 7.63 ± 2.04 | −1.910 | 0.065 | 2.188 | −1.659 | 0.050 |

| Att. Switch. | 7.28 ± 2.21 | 8.22 ± 1.58 | −1.288 | 0.207 | 1.714 | −1.384 | 0.300 |

| Att. detail | 6.71 ± 2.29 | 6.78 ± 1.99 | −0.073 | 0.942 | 2.047 | −0.862 | 0.801 |

| Comm. | 6.71 ± 2.29 | 7.44 ± 2.10 | −0.806 | 0.426 | 2.137 | −1.175 | 0.496 |

| Imagination | 4.71 ± 2.75 | 5.44 ± 1.99 | −0.800 | 0.429 | 2.151 | −1.172 | 0.499 |

| AQ tot. | 31.28 ± 10.11 | 35.52 ± 6.15 | −1.412 | 0.168 | 7.067 | −1.438 | 0.250 |

| MOOD-SR | |||||||

| Dep. Mood | 61.00 ± 1.73 | 59.63 ± 9.82 | 0.236 | 0.816 | 9.247 | −1.088 | 1.381 |

| Mani. Mood | 7.33 ± 1.15 | 10.44 ± 2.83 | −3.195 | 0.013 * | 2.686 | −2.432 | 0.151 |

| Dep. Energy | 2.00 ± 1.00 | 5.69 ± 2.15 | −2.859 | 0.011 * | 2.050 | −3.149 | −0.406 |

| Man. Energy | 3.67 ± 3.79 | 5.25 ± 2.65 | −0.897 | 0.382 | 2.804 | −1.804 | 0.691 |

| Dep. Cogn. | 10.33 ± 2.08 | 14.88 ± 5.07 | −1.499 | 0.152 | 4.817 | −2.203 | 0.343 |

| Man. Cogn. | 6.00 ± 3.61 | 8.31 ± 3.42 | −1.068 | 0.301 | 3.442 | −1.916 | 0.591 |

| Rhythm. | 14.67 ± 3.05 | 14.63 ± 3.32 | 0.020 | 0.984 | 3.294 | −1.221 | 1.246 |

| MOOD-SR tot. | 105.00 ± 6.56 | 118.81 ± 20.61 | −1.126 | 0.276 | 19.491 | −1.954 | 0.557 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dell’Osso, L.; Nardi, B.; Pini, S.; Massimetti, G.; Castellani, L.; Parri, F.; Del Grande, F.; Bonelli, C.; Concerto, C.; Di Vincenzo, M.; et al. Relationships Among Bullying Experiences, Mood Symptoms and Suicidality in Subjects with and Without Autism Spectrum Conditions. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101114

Dell’Osso L, Nardi B, Pini S, Massimetti G, Castellani L, Parri F, Del Grande F, Bonelli C, Concerto C, Di Vincenzo M, et al. Relationships Among Bullying Experiences, Mood Symptoms and Suicidality in Subjects with and Without Autism Spectrum Conditions. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101114

Chicago/Turabian StyleDell’Osso, Liliana, Benedetta Nardi, Stefano Pini, Gabriele Massimetti, Lucrezia Castellani, Francesca Parri, Filippo Del Grande, Chiara Bonelli, Carmen Concerto, Matteo Di Vincenzo, and et al. 2025. "Relationships Among Bullying Experiences, Mood Symptoms and Suicidality in Subjects with and Without Autism Spectrum Conditions" Brain Sciences 15, no. 10: 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101114

APA StyleDell’Osso, L., Nardi, B., Pini, S., Massimetti, G., Castellani, L., Parri, F., Del Grande, F., Bonelli, C., Concerto, C., Di Vincenzo, M., Della Rocca, B., Signorelli, M. S., Fusar-Poli, L., Figini, C., Politi, P., Aguglia, E., Luciano, M., & Carpita, B. (2025). Relationships Among Bullying Experiences, Mood Symptoms and Suicidality in Subjects with and Without Autism Spectrum Conditions. Brain Sciences, 15(10), 1114. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101114