The Connection Between Stress and Women’s Smoking During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Strategy for the Selection of Studies and Analysis of Results

3. Results

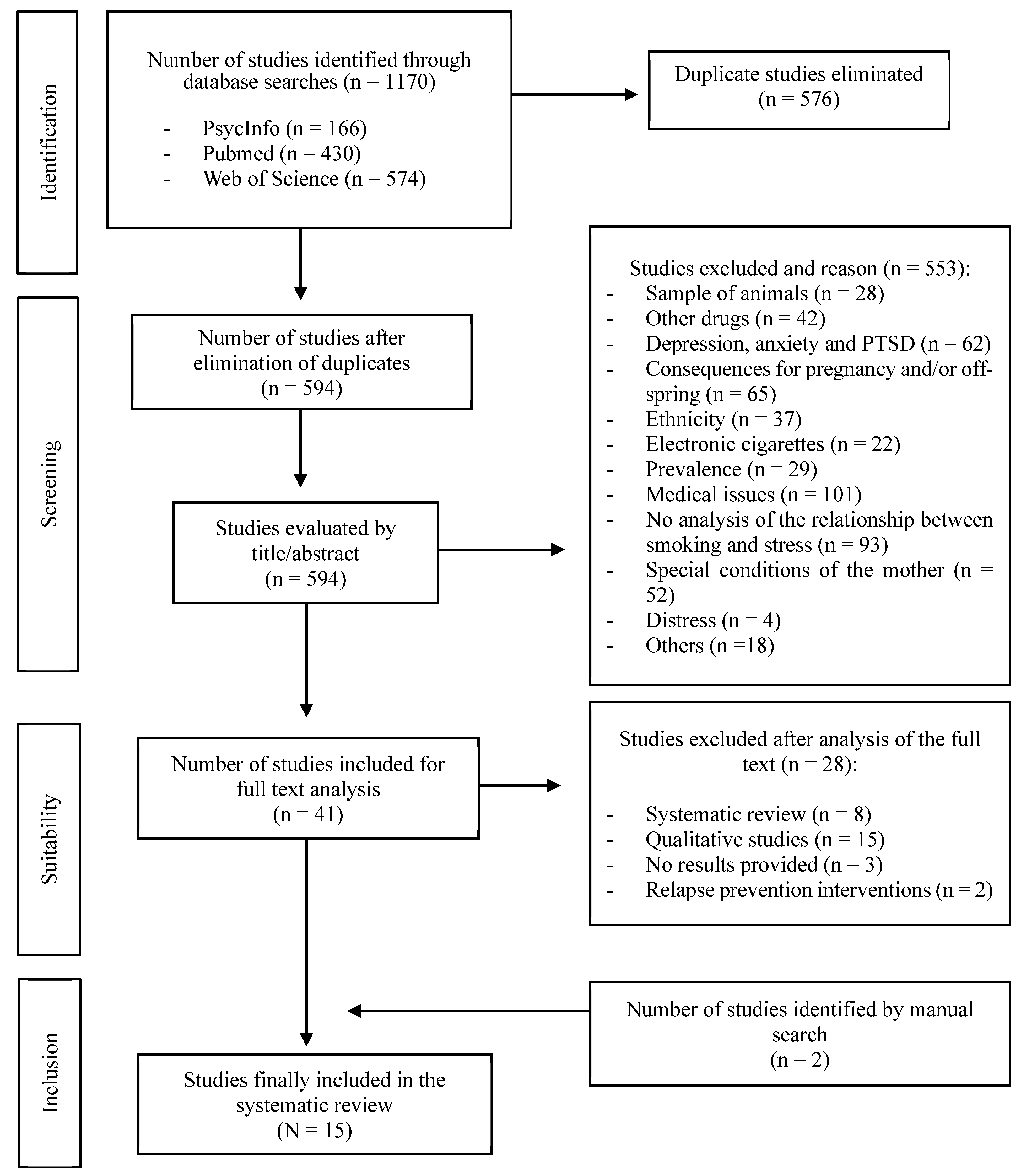

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Selected Studies

3.3. Instruments Used to Assess Stress in the Perinatal Period

3.3.1. General Instruments Assessing Stress

3.3.2. Specific Instruments Assessing Perinatal Stress

3.4. Relationship Between Stress and Tobacco Consumption

3.4.1. Relationship Between Stress and Smoking and/or Smoking Cessation During Pregnancy

3.4.2. Relationship Between Stress and Postpartum Smoking Relapse

3.5. Stress as a Cause or Consequence of Smoking in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2019: Offer Help to Quit Tobacco Use; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1g16k8b9 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Dhage, V.D.; Nagtode, N.; Kumar, D.; Bhagat, A.K. A narrative review on the impact of smoking on female fertility. Cureus 2024, 16, e58389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Action on Smoking and Health. Smoking, Pregnancy and Fertiliy; Action on Smoking and Health (ASH): Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://ash.org.uk/uploads/Smoking-Reproduction.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Jafari, A.; Rajabi, A.; Gholian-Aval, M.; Peyman, N.; Mahdizadeh, M.; Tehrani, H. National, regional, and global prevalence of cigarette smoking among women/females in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Míguez, M.C.; Pereira, B. Prevalencia y Factores de Riesgo del Consumo de Tabaco en el Embarazo Temprano [Prevalence and Risk Factors for Tobacco Use in Early Pregnancy]. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2018, 92, e201805029. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/RESP/article/view/74948 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Skalis, G.; Archontakis, S.; Thomopoulos, C.; Andrianopoulou, I.; Papazachou, O.; Vamvakou, G.; Aznaouridis, K.; Katsi, V.; Makris, T. A single-center, prospective, observational study on maternal smoking during pregnancy in Greece: The HELENA study. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2021, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J.; Popova, S. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e769–e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipling, L.; Bombard, J.; Wang, X.; Cox, S. Cigarette smoking among pregnant women during the perinatal Period: Prevalence and health care provider inquiries—Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Míguez, M.C.; Pereira, B. Factors associated with smoking relapse in the early postpartum period: A prospective longitudinal study in Spain. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.L.; Lee, T.; Hsu, C.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Chao, E.; Shih, S.F.; Hu, H.Y. Factors associated with post-partum smoking relapse in Taiwan: A trial of smoker’s helpline. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnel, T.; Ferguson, S.G.; Shiffman, S.; Schüz, B. Daily stress as link between disadvantage and smoking: An ecological momentary assessment study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Cao, C.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Menéndez-Miranda, I.; Velasco, Á.; Zurrón-Madera, P.; García-Álvarez, L.; Sáiz, P.A.; Garcia-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. Factors associated with alcohol and tobacco consumption as a coping strategy to deal with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in Spain. Addict. Behav. 2021, 121, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawless, M.H.; Harrison, K.A.; Grandits, G.A.; Eberly, L.E.; Allen, S.S. Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addict. Behav. 2015, 51, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, S.; Coleman, T.; Coleman-Haynes, T.; Ussher, M. Predictors of postpartum return to smoking: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, A.; Kang, J.S.; Vial, Y.; Ehlert, U.; Borghini, A.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Jacobs, I.; Puder, J.J. Stress exposure and psychological stress responses are related to glucose concentrations during pregnancy. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 712–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Strivens-Vilchez, H.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.; Martinez-Augustin, O.; Peralta-Ramirez, M.I. Hair cortisol levels, psychological stress and psychopathological symptoms as predictors of postpartum depression. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannigan, R.; Tanskanen, A.; Huttunen, M.O.; Cannon, M.; Leacy, F.P.; Clarke, M.C. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring psychiatric disorder: A longitudinal birth cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matas-Blanco, C.; Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A. Influence of maternal stress during pregnancy on child’s neurodevelopment. Psych 2020, 2, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowden, A.L. Stress during pregnancy and its life-long consequences for the infant. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 5055–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smejda, K.; Polanska, K.; Merecz-Kot, D.; Krol, A.; Hanke, W.; Jerzynska, J.; Stelmach, W.; Majak, P.; Stelmach, I. Maternal stress during pregnancy and allergic diseases in children during the first year of life. Respir. Care 2018, 63, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.A.C.; Espy, K.A.; Wakschlag, L. Developmental pathways from prenatal tobacco and stress exposure to behavioral disinhibition. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016, 53, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSerisy, M.; Cohen, J.W.; Dworkin, J.D.; Stingone, J.A.; Ramphal, B.; Herbstman, J.B.; Pagliaccio, D.; Margolis, A.E. Early life stress, prenatal secondhand smoke exposure, and the development of internalizing symptoms across childhood. Environ. Health 2023, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.D.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Nelson, D.B.; Smith, P.H.; Wall, M.M.; Hasin, D.S.; Nomura, Y.; Galea, S. Smoking during pregnancy in the United States, 2005-2014: The role of depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 179, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Míguez, M.C.; Pereira, B.; Pinto, T.M.; Figueiredo, B. Continued tobacco consumption during pregnancy and women’s depression and anxiety symptoms. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Version 2018; McGill University: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2018; Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Allen, A.M.; Jung, A.M.; Lemieux, A.M.; Alexander, A.C.; Allen, S.S.; Ward, K.D.; Al’absi, M. Stressful life events are associated with perinatal cigarette smoking. Prev. Med. 2019, 118, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Businelle, M.S.; Kendzor, D.E.; Reitzel, L.R.; Vidrine, J.I.; Castro, Y.; Mullen, P.D.; Velasquez, M.M.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Greisinger, A.J.; et al. Pathways linking socioeconomic status and postpartum smoking relapse. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman-Cowger, V.H.; Koszowski, B.; Rosenberry, Z.R.; Terplan, M. Factors associated with early pregnancy smoking status among low-income smokers. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, S.K.; Dabelea, D.; Lee-Winn, A.E.; Glueck, D.H.; Wilkening, G.; Perng, W. Characterization of maternal psychosocial stress during pregnancy: The Healthy Start study. Women’s Health Rep. 2022, 3, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockhill, K.M.; Tong, V.T.; Farr, S.L.; Robbins, C.L.; D’Angelo, D.V.; England, L.J. Postpartum smoking relapse after quitting during pregnancy: Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2000–2011. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.L.; Pekow, P.S.; Dole, N.; Markenson, G.; Chasan-Taber, L. Correlates of high perceived stress among pregnant Hispanic women in Western Massachusetts. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Redner, R.; Skelly, J.M.; Higgins, S.T. Examining educational attainment, prepregnancy smoking rate, and delay discounting as predictors of spontaneous quitting among pregnant smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 22, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.; Hall, L.A.; Ashford, K.; Paul, S.; Polivka, B.; Ridner, S.L. Pathways from socioeconomic status to prenatal smoking: A test of the reserve capacity model. Nurs. Res. 2017, 66, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, R.A.; Ajayi, K.V.; Dhaurali, S.; Carvalho, K.; Kheyfets, A.; Lawrence, B.C.; Amutah-Onukagha, N. Investigating the role of race and stressful life events on the smoking patterns of pregnant and postpartum women in the United States: A multistate pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system phase 8 (2016–2018) Analysis. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijers, C.; Ormel, J.; Meijer, J.L.; Verbeek, T.; Bockting, C.L.; Burger, H. Stressful events and continued smoking and continued alcohol consumption during mid-pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crone, M.R.; Luurssen-Masurel, N.; Bruinsma-van Zwicht, B.S.; van Lith, J.M.M.; Rijnders, M.E.B. Pregnant women at increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: A combination of less healthy behaviors and adverse psychosocial and socio-economic circumstances. Prev. Med. 2019, 127, 105817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.L.; Nelson, C.R.; Greaves, L. Smoking cessation during pregnancy and relapse after childbirth in Canada. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2015, 37, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Širvinskienė, G.; Žemaitienė, N.; Jusienė, R.; Šmigelskas, K.; Veryga, A.; Markūnienė, E. Smoking during pregnancy in association with maternal emotional well-being. Medicina 2016, 52, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Â.T.L.; Rodrigues-Junior, A.L.; Gomes, N.C.; Martinis, B.S.D.; Baddini-Martinez, J.A. Socio-demographic and psychological features associated with smoking in pregnancy. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2021, 47, e20210050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, R.; Robertson, A. The Life Events Inventory: A measure of the relative severity of psycho-social stressors. J. Psychosom. Res. 1973, 17, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yali, A.M.; Lobel, M. Stress-resistance resources and coping in pregnancy. Anxiety Stress Coping 2002, 15, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Kafetsios, K.; Statham, H.E.; Snowdon, C.M. Factor structure, validity and reliability of the Cambridge Worry Scale in a pregnant population. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.A.; Williams, C.A.; Greenberg, R.S. Supports, stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income mothers of young children. Am. J. Public Health 1985, 75, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology for PRAMS Surveillance System; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/prams/php/methodology/index.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Newton, R.W.; Hunt, L.P. Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and its relation to low birth weight. Br. Med. J. 1984, 288, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, J.; Pembrey, M.; Jones, R.; ALSPAC Study Team. ALSPAC–the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2001, 15, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härkönen, J.; Lindberg, M.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Scheinin, N.M. Education is the strongest socio-economic predictor of smoking in pregnancy. Addiction 2018, 113, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxson, P.J.; Edwards, S.E.; Ingram, A.; Miranda, M.L. Psychosocial differences between smokers and non-smokers during pregnancy. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, B.; Veronese, N.; Vancampfort, D.; Prina, A.M.; Lin, P.Y.; Tseng, P.T.; Evangelou, E.; Solmi, M.; Kohler, C.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. Perceived stress and smoking across 41 countries: A global perspective across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melisa, B.; Meghea, C.; Blaga, O.; Hostina, A. Risk factors for postnatal smoking relapse among Romanian women. Tob. Prev. Cessation 2018, 4, A141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.B.; Simmons, V.N.; Sutton, S.K.; Meltzer, L.R.; Brandon, T.H. A content analysis of attributions for resuming smoking or maintaining abstinence in the post-partum period. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, C.; Fernandez, S.P.; Pantouli, F.; Meye, F.J.; Marti, F.; Tolu, S.; Parnaudeau, S.; Marie, H.; Tronche, F.; Maskos, U.; et al. Nicotinic receptors mediate stress-nicotine detrimental interplay via dopamine cells’ activity. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyal, D.; Sutter, A.L.; Auriacombe, M.; Serre, F.; Calcagni, N.; Rascle, N. Stigma attached to smoking pregnant women: A qualitative insight in the general French population. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.C.; Pereira, B. Prevalence of smoking in pregnancy: Optimization of the diagnosis. Med. Clin. 2018, 151, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Gebel, K.; Oldenburg, B.F.; Wan, X.; Zhong, X.; Novotny, T.E. An early-stage epidemic: A systematic review of correlates of smoking among Chinese women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 21, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, O.V.; O’Dell, L.E. Stress is a principal factor that promotes tobacco use in females. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 65, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelghaffar, W.; Daoud, M.; Philip, S.; Ransing, R.; Jamir, L.; Jatchavala, C.; Pinto da Costa, M. Perinatal mental health programs in low and middle-income countries: India, Thailand, and Tunisia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2023, 88, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Businelle et al. (2013) [29] | Silveira et al. (2013) [33] | Beijers et al. (2014) [37] | White et al. (2014) [34] | Gilbert et al. (2015) [39] | Coleman-Cowger et al. (2016) [30] | Rockhill et al. (2016) [32] | Širvinskienė et al. (2016) [40] | Míguez and Pereira (2018) [6] | Yang et al. (2017) [35] | Allen et al. (2019) [28] | Crone et al. (2019) [38] | Fujita et al. (2021) [41] | Dhaliwal et al. (2022) [31] | Yakubu et al. (2023) [36] | ||

| Instruments | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | |||||||||||||||

| Life Events Inventory (LEI) | ||||||||||||||||

| Ad hoc question on stress in pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||

| Ad hoc questionnaire on stressful or traumatic experiences | ||||||||||||||||

| Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (NuPDQ) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cambridge Worry Scale (CWS) | ||||||||||||||||

| Everyday Stressors Index (ESI) | ||||||||||||||||

| Stressful Life Events of PRAMS (PRAMS SLE) | ||||||||||||||||

| Event questionnaire | ||||||||||||||||

| Study | Objective | Sample | Stress Assessment | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * Silveira et al. (2013) [33] USA | To assess the correlates of high levels of perceived stress in a group of Hispanic women with high levels of stress during pregnancy. | 979 Hispanic pregnant women screened at 12, 21 and 30 weeks of pregnancy. | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | The relationship between stress and smoking was significant, with a greater number of cigarettes associated with higher stress scores (OR = 2.2; p < 0.05). | Tobacco consumption increases the likelihood that women will experience stress during pregnancy. |

| Beijers et al. (2014) [37] The Netherlands | To examine whether the severity of different types of EVD is associated with continued smoking during mid-pregnancy. | 2287 pregnant women (14–19 weeks) - Continued smoking: 113 - Quit smoking: 290 - Non-smokers: 1883 | Event questionnaire | Perceived severity of SLE was not significantly associated with continued smoking in pregnant women (p > 0.05). | There is an association between SLE and smoking during pregnancy. However, smoking was not associated with the severity of SLE. |

| * White et al. (2014) [34] USA | To investigate possible predictors of spontaneous quitting among pregnant smokers, including stress. | 349 pregnant women (>25 weeks) - Quit smoking: 118 - Continued smoking: 231 | Not stated | Mean stress scores: - Quit smoking: 4.7 - Continued smoking: 5.5 (p < 0.01) | Women who quit smoking reported lower average levels of stress than women who continued to smoke. |

| * Gilbert et al. (2015) [39] Canada | To analyse the rates and determinants of smoking cessation during pregnancy. | 1586 women who had a baby and were smoking before pregnancy. Subjects were interviewed between 5 and 15 months after delivery. | Ad hoc question on stress in the 12 months prior to delivery | Stress before or during pregnancy was associated with higher odds of not quitting smoking during pregnancy (OR = 1.39). | Stress reduces the likelihood that women will quit smoking during pregnancy. |

| * Coleman-Cowger et al. (2016) [30] USA | To identify differences between pregnant women who currently smoke and those who quit smoking 90 days before their first antenatal visit. | 130 pregnant women (1st or 2nd trimester) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | Women who smoked during pregnancy had higher mean stress scores than those who quit (p < 0.05). | Higher stress increases the likelihood of continued smoking, and lower stress increases the likelihood of quitting. |

| * Širvinskienė et al. (2016) [40] Lithuania | To investigate psychosocial predictors of smoking during pregnancy, including stress and distress. | 514 mothers assessed between the second and third day after delivery. | Ad hoc questions about emotional stress during pregnancy. | Percentage of women with stress: - Smokers: 19.4% - Non-smokers: 13.8% (p > 0.05) | Stressful experiences were not significantly related to smoking during pregnancy. |

| * Yang et al. (2017) [35] USA | To assess the role of chronic stress levels in explaining the relationship between socioeconomic status and persistent prenatal smoking. | 370 pregnant women evaluated at 5–13, 14–26 and 27–36 weeks gestation. - 84 smokers - 202 non-smokers - 84 quit spontaneously | Everyday Stressors Index (ESI) | Average chronic stress scores: - Smokers: 33.5 - Non-smokers: 27.8 - Spontaneous quitters: 33.5 (p < 0.001) | Mean scores on chronic stress are higher in the group of smokers than in non-smokers and those who quit smoking spontaneously. Stress during pregnancy is significantly related to smoking. |

| * Míguez and Pereira (2018) [6] Spain | To assess the prevalence of smoking in the first trimester of pregnancy and associated variables. | 760 pregnant women (<20 weeks) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | Mean scores on the PSS-14: - Smokers: 21.26 - Non-smokers: 16.24 (p < 0.001). | Women who smoked had higher mean levels of stress than non-smokers. Stress predicts smoking during pregnancy. |

| * Allen et al. (2019) [28] USA | To examine the association between SVEs in the year prior to delivery and perinatal smoking. | 15,136 pregnant women - 7308 smokers - 7828 non-smokers | Life Events Inventory (LEI) | Mean stress scores: - Smokers: 3.29 - Non-smokers: 2.53 (p < 0.001) | Stress significantly increases the likelihood of women smoking during pregnancy. |

| Crone et al. (2019) [38] The Netherlands | To identify different groups of pregnant women according to their behavioural, psychosocial and socio-economic characteristics in health behaviour during pregnancy. | 2455 women (12 weeks) - 3.8% continued smoking - 10.2% quit spontaneously - 86% never smoked during pregnancy | Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (NuPDQ)Cambridge Worry Scale (CWS) | Mean NuPDQ scores: - Non-smokers: 1.8 - Quit: 4 - Smokers: 11.8Mean CWS scores: - Non-smokers: 1.9 - Quit: 3.6 - Smokers: 6.5 | There is a link between stress and smoking during pregnancy. |

| * Fujita et al. (2021) [41] Brazil | To investigate how social and psychological characteristics differ between women who smoke and women who do not smoke during pregnancy. | 269 pregnant women (< 24 weeks) - Smokers: 94 - Non-smokers: 175 | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | Mean scores on the PSS-14: - Smokers: 24.7 - Non-smokers: 18.5 (OR = 1.07; p < 0.001). | Women who continued to smoke during pregnancy have higher mean scores on perceived stress than non-smokers. |

| * Dhaliwal (2022) [31] USA | To characterise maternal psychosocial stress to identify socio-demographic, biological, behavioural and health correlates of stress domains (overwhelm, anhedonia and lack of control). | 1079 pregnant women (17–27 weeks) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | Smoking during pregnancy was associated with the domain of lack of stress control (p < 0.005). | Analysis of the domains of stress and its relationship to smoking in pregnancy provides some insight into which specific stress symptoms are related to smoking in pregnant women. |

| * Yakubu et al. (2023) [36] USA | To examine smoking patterns in pregnant women who experienced SLE. | 24,209 pregnant women (3rd trimester) - 1841 smokers - 21,990 non-smokers | Stressful Life Events of PRAMS (PRAMS SLE) | Of the group of women with the highest stress: - Smokers: 9.7% - Non-smokers: 1.6% (p < 0.001) | Women who reported higher stress were more likely to smoke during pregnancy. |

| Study | Objective | Sample | Stress Assessment | Results | Conclusions |

| * Businelle et al. (2013) [29] USA | To examine, using different models, the multiple mechanisms linking socio-economic status to postpartum smoking relapse. | 251 postpartum women who quit smoking before or during pregnancy. Subjects were divided into two groups: - Relapsed - Remained abstinent | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) | The correlation between the PSS-14 scores and relapse was 0.145 (p < 0.05). The correlation between PSS-14 scores and craving: - Urge to smoke: 0.203 - Thinking about smoking: 0.306 - Desire to smoke: 0.196 (p < 0.001) | Stress was significantly related to smoking relapse after 8 weeks postpartum, as women who had relapsed reported higher levels of stress. In addition, stress was significantly related to different symptoms of craving. |

| * Rockhill et al. (2016) [32] USA | Identify characteristics associated with postpartum smoking relapse. | 13,076 women | Stressful Life Events of PRAMS (PRAMS SLE) | Percentage of women who relapsed: -With 1–2 stressors: 37.9% -With more than 6 stressors: 49.7% (p < 0.001) | The percentage of women who relapsed increased significantly with the number of stressors they had experienced. |

| * Allen et al. (2019) [28] USA | To examine the association between SLEs and postpartum smoking relapse. | 7151 women - 31,226 relapsed - 4025 remained abstinent | Life Events Inventory (LEI) | Average SLE scores - Relapsed: 2.71 - Abstinent: 2.35 (p < 0.001) | Mean SLE scores were significantly higher in the group of women who relapsed postpartum. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Míguez, M.C.; Queiro, Y.; Posse, C.M.; Val, A. The Connection Between Stress and Women’s Smoking During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010013

Míguez MC, Queiro Y, Posse CM, Val A. The Connection Between Stress and Women’s Smoking During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleMíguez, M. Carmen, Yara Queiro, Cristina M. Posse, and Alba Val. 2025. "The Connection Between Stress and Women’s Smoking During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 15, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010013

APA StyleMíguez, M. C., Queiro, Y., Posse, C. M., & Val, A. (2025). The Connection Between Stress and Women’s Smoking During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 15(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010013