Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Population

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measurements

- Beck’s Hopelessness Scale [38]. This scale subjectively assesses people’s negative expectations about their future. It is also a potential surrogate predictor of suicidal behaviour. It consists of 20 true/false items. The total score varies between 0 and 20 and is the sum of all the items. The cut-off point is set at scores equal to or greater than 9. Scores above these values are considered to be good predictors of suicide risk [39].

- Rosenberg self-esteem scale [40]. This is one of the most widely used scales for the global measurement of self-esteem. It consists of 10 items focusing on feelings of respect and self-acceptance. It is a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3, where the person reflects their level of agreement or disagreement with the items. The total score is the sum of all items and ranges from 0 to 30. Low self-esteem is defined as a score below 15, while higher scores indicate higher self-esteem [41].

- State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [42]. This questionnaire consists of 40 items: 20 items to assess state anxiety (A-S) and 20 to assess trait anxiety (A-F). It has a Likert scale from 0 to 3 according to its intensity (state) and frequency of occurrence (trait). Two total scores are obtained, one for A-S and one for A-F, ranging from 0 to 60, with higher scores corresponding to greater anxiety. These direct scores are transformed into quantiles according to gender and age [43].

- Plutchik’s Impulsivity Scale [44]. This scale assesses, among other things, one’s previous suicide attempts and the intensity of their current suicidal ideation. It consists of 15 items scored from 0 to 3 depending on the occurrence of impulsive behaviour. The total score is the sum of all the scores and ranges from 0 to 45. In the Spanish version, the cut-off point is 20; values below that score indicate low impulsivity. The higher the score, the greater the tendency for impulsive behaviour [45].

- World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) [46]. The 36-item version measuring health and disability was used, which assessed the level of functioning in 6 life domains in the 30 days prior to the test. These domains are cognition, mobility, personal care, relationships, activities of daily living, and participation in society. Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“no difficulty”) to 5 (“extreme difficulty”). The total score for each dimension is calculated by weighting the questions and the severity levels obtained; the score ranges from 0 (without disability) to 100 (total disability) [47,48].

- Abbreviated World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) [49]. This is an abbreviated version of a WHO questionnaire consisting of 26 questions about quality of life as perceived by patients during the previous 2 weeks. It assesses physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental context. In each of those areas, a direct score is obtained based on percentiles. The higher the score, the higher the perceived quality of life [50].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

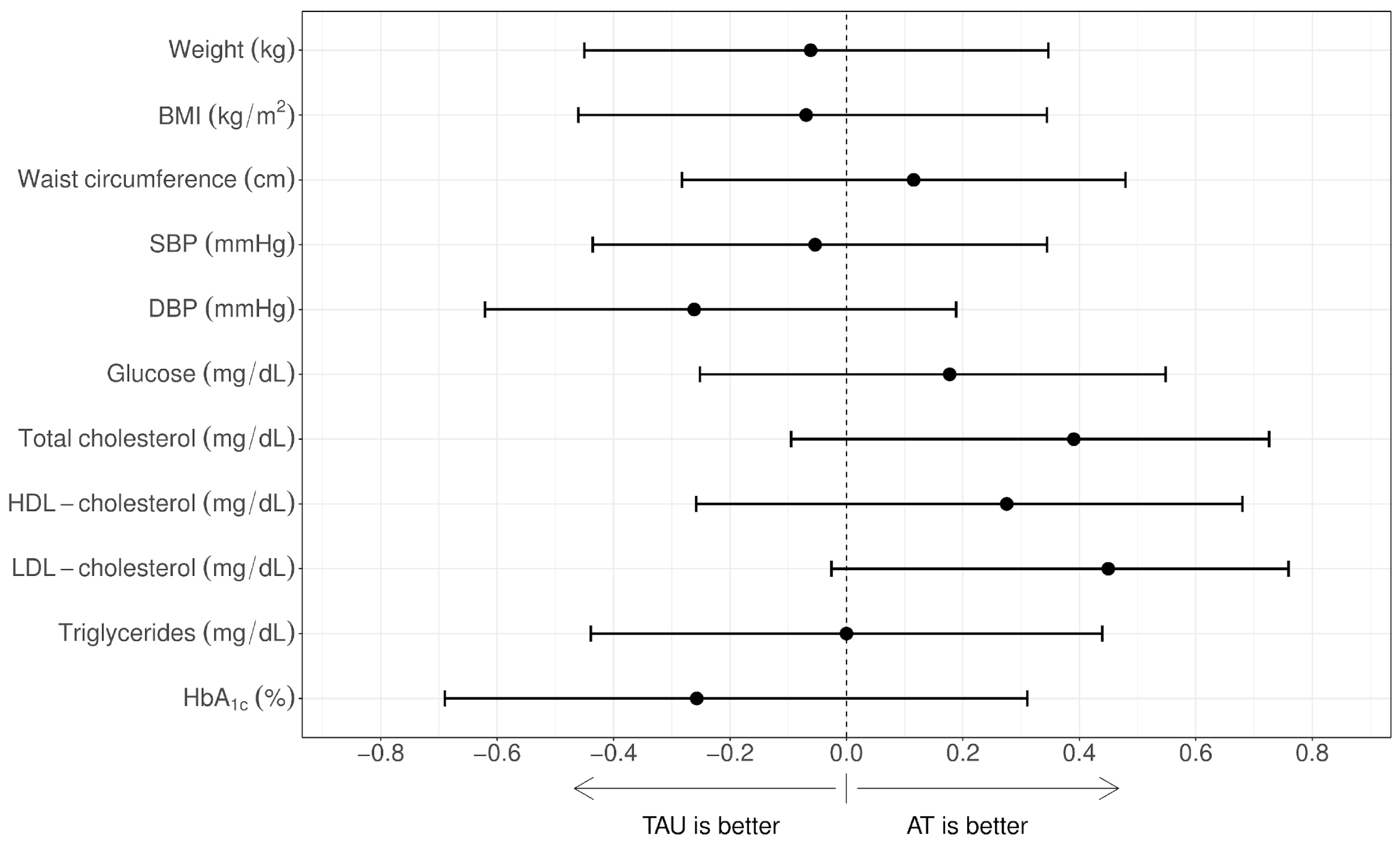

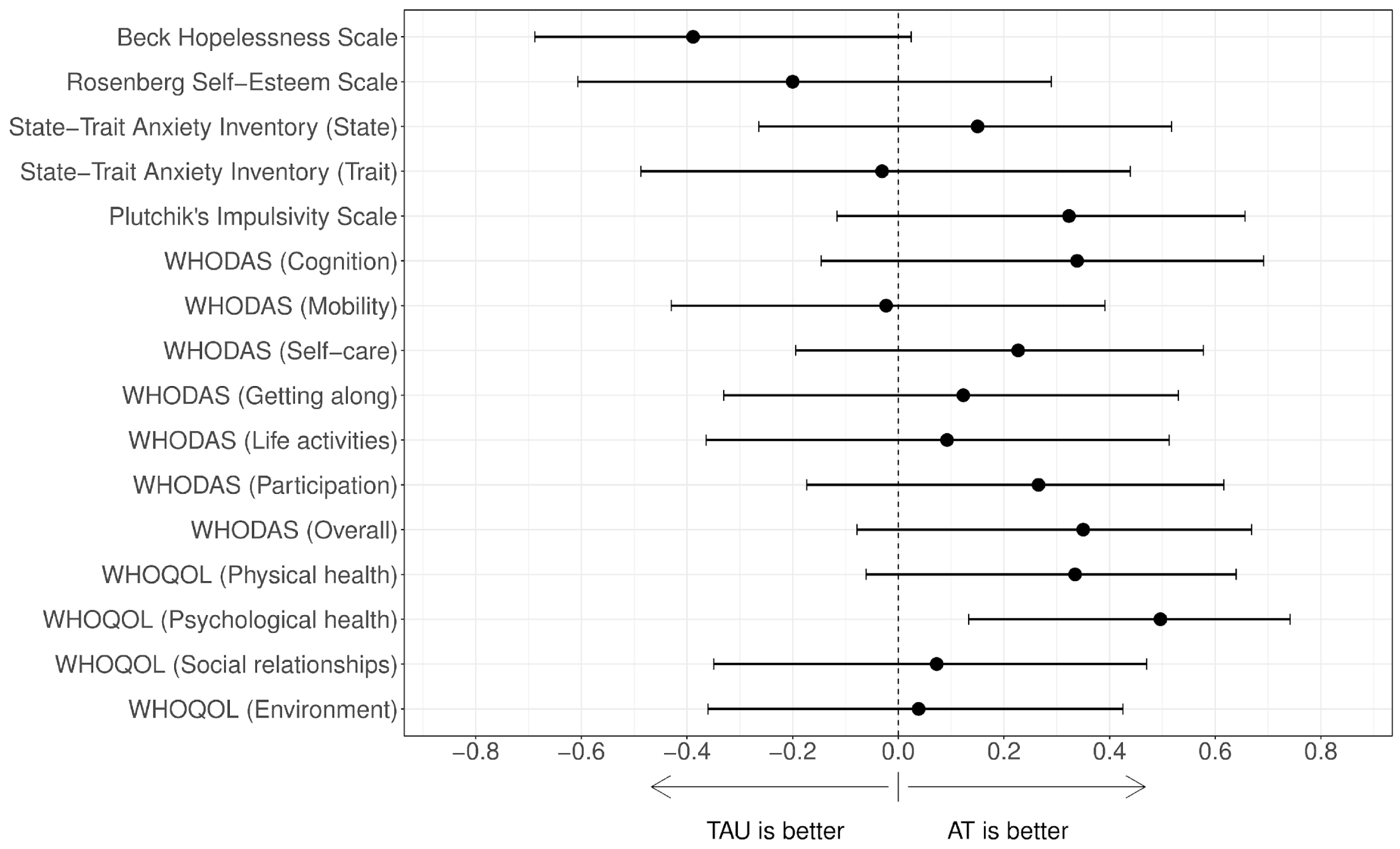

3.1. Short-Term Effectiveness

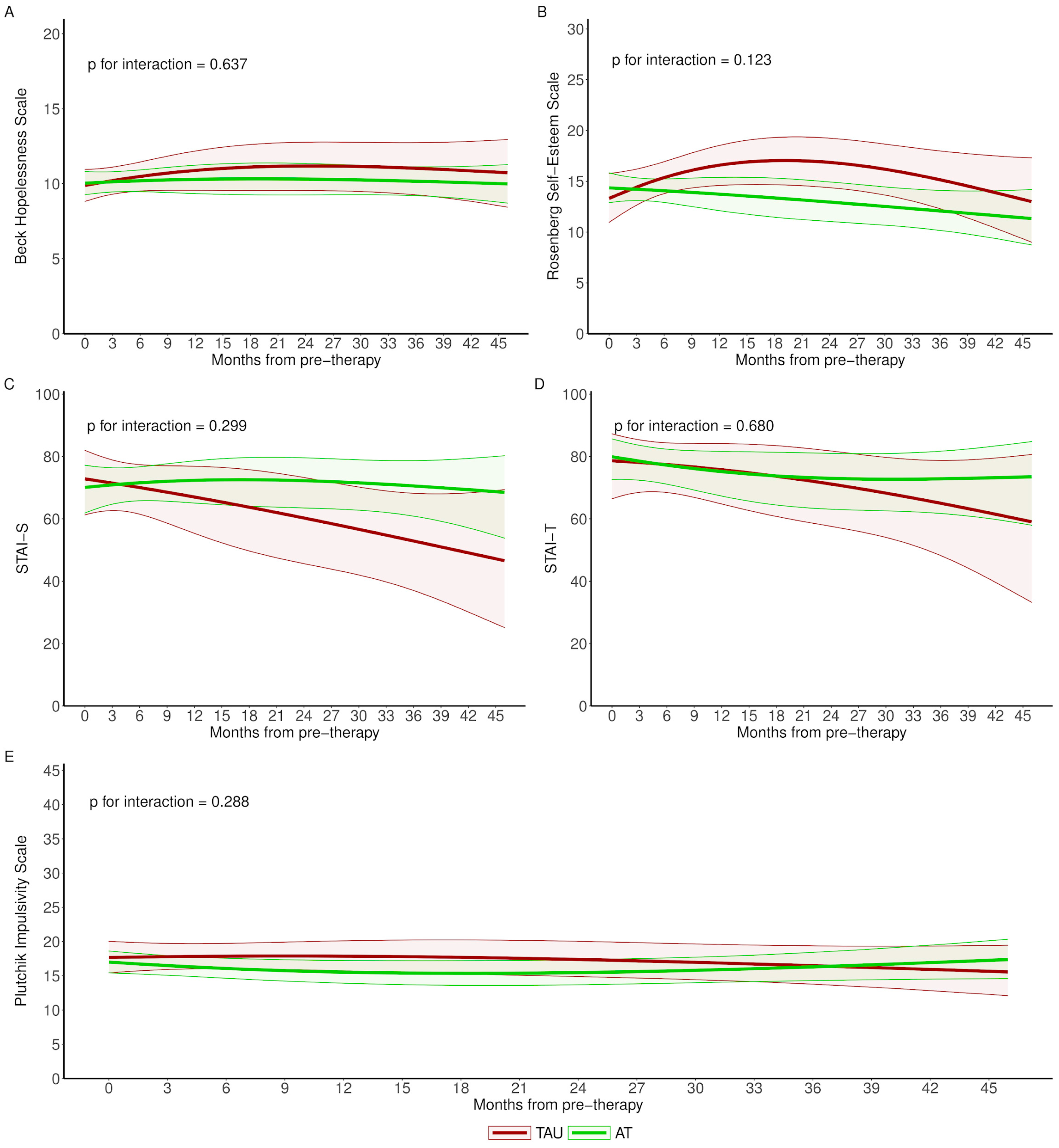

3.2. Long-Term Effectiveness

4. Discussion

Practical Issues to Consider in AT Programmes for Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Widiger, T.A.; Widiger, T. The Oxford Handbook of Personality Disorders; OUP USA: Oxford, UK, 2012; 856p. [Google Scholar]

- Skodol, A.E.; Gunderson, J.G.; Pfohl, B.; Widiger, T.A.; Livesley, W.J.; Siever, L.J. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; Médica Panamericana: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014; pp. 645–684. [Google Scholar]

- Skodol, A.E.; Gunderson, J.G.; McGlashan, T.H.; Dyck, I.R.; Stout, R.L.; Bender, D.S.; Grilo, C.M.; Shea, M.T.; Zanarini, M.C.; Morey, L.C.; et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gabalawy, R.; Katz, L.Y.; Sareen, J. Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Gordon, K.L.; Whalen, D.J.; Layden, B.K.; Chapman, A.L. A Systematic Review of Personality Disorders and Health Outcomes. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2015, 56, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, A.D.; Oltmanns, T.F. Borderline personality pathology and chronic health problems in later adulthood: The mediating role of obesity. Pers. Disord. 2013, 4, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.N.; Jackson, H.; Cavelti, M.; Betts, J.; McCutcheon, L.; Jovev, M.; Chanen, A.M. Number of Borderline Personality Disorder Criteria and Depression Predict Poor Functioning and Quality of Life in Outpatient Youth. J. Pers. Disord. 2020, 34, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oud, M.; Arntz, A.; Hermens, M.L.; Verhoef, R.; Kendall, T. Specialized psychotherapies for adults with borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffers-Winterling, J.M.; Storebø, O.J.; Kongerslev, M.T.; Faltinsen, E.; Todorovac, A.; Sedoc Jørgensen, M.; Sales, C.P.; Callesen, H.E.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Völlm, B.A.; et al. Psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: A focused systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2022, 221, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristea, I.A.; Gentili, C.; Cotet, C.D.; Palomba, D.; Barbui, C.; Cuijpers, P. Efficacy of Psychotherapies for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendo-Cullell, M.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Forné, C.; Fernández-Oñate, D.; Ruiz de Cortázar-Gracia, N.; Facal, C.; Torrent, A.; Palacios, R.; Pifarré, J.; Batalla, I. A pilot study of the efficacy of an adventure therapy programme on borderline personality disorder: A pragmatic controlled clinical trial. Pers. Ment. Health 2021, 15, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Neill, J.T. A Meta-Analysis of Adventure Therapy Outcomes and Moderators. Open Psychol. J. 2013, 6, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Producción científica de Terapia Aventura-Terapia Aventura [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://terapiaaventura.es/produccion-cientifica-de-terapia-aventura/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Gass, M.A.; Gillis, H.L.; Russell, K.C.; Hallow, G. Adventure Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; 426p. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Donado, S.; Fernández-Gavira, J.; Muñoz-Llerena, A. Propuesta de programa de Terapia de Aventura para Adolescentes con Síndrome de Asperger. E-Motion Rev. Educ. Mot. E Investig. 2020, 14, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, V.; Golins, G. The Exploration of the Outward Bound Process; Colorado Outward Bound School: Carbondale, CO, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, C.; Doebler, P.; Bürkner, P.C.; Holling, H. Adventure Therapy Effects on Self-Concept—A Meta-Analysis [Internet]. PsyarXiv 2017. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/c7y9a/ (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Houge Mackenzie, S.; Son, J.S.; Hollenhorst, S. Unifying Psychology and Experiential Education: Toward an Integrated Understanding of Why It Works. J. Exp. Educ. 2014, 37, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Introducing Adventure Therapy in Spain: Lights and Shadows. En Adventure Therapy around the Globe: International Perspectives and Diverse Approaches, 2015; European Arts & Science Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013; pp. 280–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, A.; Ruiz de Cortázar Gracia, N. Historical Background of Adventure Therapy in Spain. Available online: http://adventuretherapy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ATE_AT-History-ESP_2017.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Zachor, D.A.; Vardi, S.; Baron-Eitan, S.; Brodai-Meir, I.; Ginossar, N.; Ben-Itzchak, E. The effectiveness of an outdoor adventure programme for young children with autism spectrum disorder: A controlled study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.; Feinstein, J.; Spavor, J.; Kidd, S. An Examination of the Feasibility of Adventure-Based Therapy in Outpatient Care for Individuals with Psychosis. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2013, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, C.; Dubé, J.; Abdel-Baki, A.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C. Off the beaten path: Adventure Therapy as an adjunct to early intervention for psychosis. Psychosis 2021, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.T.; Lau, H.Y.; Chan, W.Y.; Cheung, C.W.; Lui, W.; Chane-Thu, Y.S.J.; Dai, W.L.; To, K.C.; Cheng, H.L. Adventure therapy for child, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann, J.; Gillis, H.; Speelman, E.; Parry, K.; Case, J. A Meta-analysis of Wilderness Therapy Outcomes for Private Pay Clients. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, N.J.; Fernee, C.R.; Gabrielsen, L.E. Nature’s Role in Outdoor Therapies: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohus, M.; Stoffers-Winterling, J.; Sharp, C.; Krause-Utz, A.; Schmahl, C.; Lieb, K. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 398, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi, S.; Deane, F.P.; Mooney-Reh, D.; Bailey, A.; Ciaglia, D. Experiential avoidance and depression predict values engagement among people in treatment for borderline personality disorder. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; McGlashan, T.H.; Skodol, A.E. Stability and course of personality disorders: The need to consider comorbidities and continuities between axis I psychiatric disorders and axis II personality disorders. Psychiatr. Q. 2000, 71, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, J.G.; Shea, M.T.; Skodol, A.E.; McGlashan, T.H.; Morey, L.C.; Stout, R.L.; Zanarini, M.C.; Grilo, C.M.; Oldham, J.M.; Keller, M.B. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J. Pers. Disord. 2000, 14, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Hennen, J.; Reich, D.B.; Silk, K.R. Psychosocial functioning of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. J. Pers. Disord. 2005, 19, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzenweger, M.F. Stability and change in personality disorder features: The Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gratz, K.L.; Gunderson, J.G. Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav. Ther. 2006, 37, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Davis, D.D.; Freeman, A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, N.J.; Peeters, L.; Carpenter, C. Adventure Therapy. In Adbenture Programming and Traver in the 21st Century; Black, R., Bricker, K.S., Eds.; Venture Publishing: Edmonton, AB, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tanne, J.H.; Hayasaki, E.; Zastrow, M.; Pulla, P.; Smith, P.; Rada, A.G. COVID-19: How doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ 2020, 368, m1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Weissman, A.; Lester, D.; Trexler, L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, J.A.; de los Ríos, L.R.; Díaz, C.R.P.; León, A.F.; Enríquez, J. Escala de desesperanza de Beck (BHS): Adaptación y características psicométricas. Rev. Investig. Psicol. 2006, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015; 339p. [Google Scholar]

- Morejón, A.J.V.; García-Bóveda, R.J.; Jiménez, R.V.M. Escala de autoestima de Rosenberg: Fiabilidad y validez en población clínica española. Apunt. Psicol. 2004, 22, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.; Jacobs, G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1–Y2); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, A.G.; Casal, G.B. Actualización psicométrica y funcionamiento diferencial de los ítems en el State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Psicothema 2011, 23, 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R.; Van Praag, H. The measurement of suicidality, aggressivity and impulsivity. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, S23–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Colorado, Y.; Palacio-Sañudo, J.; Caballero-Domínguez, C.C.; Pineda-Roa, C.A. Adaptación, validez de constructo y confiabilidad de la escala de riesgo suicida Plutchik en adolescentes colombianos. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2019, 51, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/measuring-health-and-disability-manual-for-who-disability-assessment-schedule-(-whodas-2.0) (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Medición de la Salud y la Discapacidad: Manual Para el Cuestionario de Evaluación de la Discapacidad de la OMS: WHODAS 2.0 [Internet]; Servicio Nacional de Rehabilitación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015; 140p, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/170500 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Vazquez-Barquero, J.; Bourgon, E.; Herrera Castanedo, S.; Saiz, J.; Uriarte, M.; Morales, F.; Gaite, L.; Herran, A.; Ustun, T.B.; y Grupo Cantabria en Discapacidades. Version en lengua española de un nuevo cuestionario de evaluacion de discapacidades de la OMS (WHO-DAS-II): Fase inicial de desarrollo y estudio piloto. Grupo Cantabria en Discapacidades. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2000, 28, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Division of Mental Health. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment: Field Trial Version, December 1996 [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996; Report No.: WHOQOL-BREF; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63529 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Lucas-Carrasco, R. The WHO quality of life (WHOQOL) questionnaire: Spanish development and validation studies. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2012, 21, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.; Kromrey, J.; Coraggio, J.; Skowronek, J. Appropriate statistics for ordinal level data: Should we really be using t-test and Cohen’sd for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other surveys? Annu. Meet. Fla. Assoc. Institutional Res. 2006, 177, 34. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Torchiano, M. Effsize: Efficient Effect Size Computation [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=effsize (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Rizopoulos, D. GLMMadaptive: Generalized Linear Mixed Models Using Adaptive Gaussian Quadrature [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://drizopoulos.github.io/GLMMadaptive/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis [Internet]; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, K.; Krogh, J.; Wenneberg, C.; Jessen, H.K.L.; Krakauer, K.; Gluud, C.; Thomsen, R.R.; Randers, L.; Nordentoft, M. Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus collaborative assessment and management of suicidality treatment for reduction of self-harm in adults with borderline personality traits and disorder-a randomized observer-blinded clinical trial. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, K.G.; Greggersen, W.; Schweiger, U.; Cordes, J.; Correll, C.U.; Frieling, H.; Balijepalli, C.; Lösch, C.; Moebus, S. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with borderline personality disorder: Results from a cross-sectional study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 263, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.A.; Ringwald, W.R.; Wright, A.G.C.; Manuck, S.B. Borderline personality disorder traits associate with midlife cardiometabolic risk. Pers. Disord. 2020, 11, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, A.E.; Sahlin, H.; Liu, S.; Lu, Y.; Lundström, S.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Kuja-Halkola, R. Borderline personality disorder: Associations with psychiatric disorders, somatic illnesses, trauma, and adverse behaviors. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2514–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Barone, L.; Fiore, D.; Marchini, M.; Pazzano, P.; Ramella, P.; Riccardi, I.; Sanza, M.; Maffei, C. Emotion Regulation, Physical Diseases, and Borderline Personality Disorders: Conceptual and Clinical Considerations. Front. Psychol. 2021. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.567671 (accessed on 12 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Lange, S.M.M. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: Overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.A.; Riniolo, T.C.; Porges, S.W. Borderline personality disorder and emotion regulation: Insights from the Polyvagal Theory. Brain Cogn. 2007, 65, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.L.; Díaz-Marsá, M.; Pastrana, J.I.; Molina, R.; Brotons, L.; López-Ibor, M.I.; López-Ibor, J.J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response in borderline personality disorder without post-traumatic features. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2007, 190, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Weiss, N.H.; McDermott, M.J.; Dilillo, D.; Messman-Moore, T.; Tull, M.T. Emotion Dysregulation Mediates the Relation between Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms and Later Physical Health Symptoms. J. Pers. Disord. 2017, 31, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, J.; Lane, S.P.; Carpenter, R.W.; Trull, T.J. Linking Daily-Life Interpersonal Stressors and Health Problems Via Affective Reactivity in Borderline Personality and Depressive Disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2020, 82, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Neill, J.T.; Crisp, S.J.R. Wilderness adventure therapy effects on the mental health of youth participants. Eval. Program Plan. 2016, 58, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storebø, O.J.; Stoffers-Winterling, J.M.; Völlm, B.A.; Kongerslev, M.T.; Mattivi, J.T.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Faltinsen, E.; Todorovac, A.; Sales, C.P.; Callesen, H.E.; et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD012955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaweera, N.; Hunt, K.; Camp, J. A Qualitative Evaluation of Young People’s, Parents’ and Carers’ Experiences of a National and Specialist CAMHS Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Outpatient Service. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spodenkiewicz, M.; Speranza, M.; Taïeb, O.; Pham-Scottez, A.; Corcos, M.; Révah-Levy, A. Living from day to day-qualitative study on borderline personality disorder in adolescence. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry J. Acad. Can. Psychiatr. Enfant. Adolesc. 2013, 22, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, S.F.; Jansen, J.E.; Petersen, C.J.; Jensen, R.; Simonsen, E. Mobile App Integration Into Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Persons with Borderline Personality Disorder: Qualitative and Quantitative Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e14913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Parra, Y.; Guerrero Santiesteban, K.; Cárdenas, S. Validación del Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) en una Muestra Universitaria de Bogotá, Colombia. 2015. Available online: https://repository.usta.edu.co/handle/11634/3389 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Mairal, J.B. Spanish Adaptation of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ). Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2004, 4, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, G.; Jódar, R. Adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional. Clín. Salud. 2008, 19, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Trabucco, C.; Urzúa, M.A.; Garrido, L.; Leiva, J. Validez y Confiabilidad de la Versión Adaptada al Español de la Escala de Dificultades de Regulación Emocional (DERS-E) en Población Chilena. Ter. Psicol. 2014, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 26 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 17 (65.4) | 6 (60) |

| Age (years) | 39.5 (31.8, 45.0) | 39.0 (29.2, 51.2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 13 (50) | 8 (80) |

| Married | 8 (30.8) | 2 (20) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) |

| Others | 2 (7.69) | 0 (0) |

| Cohabitation situation | ||

| Live alone | 6 (23.1) | 2 (20) |

| Lives with family | 14 (53.8) | 6 (60) |

| Cohabiting | 6 (23.1) | 1 (10) |

| Others | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 2 (7.69) | 2 (20) |

| Secondary | 12 (46.2) | 5 (50) |

| University | 12 (46.2) | 3 (30) |

| Profession | ||

| No profession | 3 (11.5) | 3 (30) |

| Student | 4 (15.4) | 2 (20) |

| Non-qualified labour | 5 (19.2) | 1 (10) |

| Qualified work | 14 (53.8) | 4 (40) |

| Employment situation | ||

| Active | 6 (23.1) | 2 (20) |

| Sick leave | 9 (34.6) | 2 (20) |

| Unemployed | 6 (23.1) | 4 (40) |

| Pensioner | 5 (19.2) | 2 (20) |

| Secondary diagnosis | ||

| Bipolar affective disorder | 1 (4) | 1 (11.1) |

| Unipolar affective disorder | 11 (44) | 6 (66.7) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Anxiety Disorder | 4 (16) | 1 (11.1) |

| Adaptive disorder | 3 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Substance use disorder | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Eating Disorder | 3 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Others | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Tobacco | 8 (30.8) | 4 (40) |

| Other toxic | ||

| None | 20 (76.9) | 9 (90) |

| Alcohol | 4 (15.4) | 1 (10) |

| Cannabis | 2 (7.69) | 0 (0) |

| Pre-Treatment Assessment | Post-Treatment Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 26 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 10 | Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 26 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 10 | |

| Weight (kg) | 78.6 (66.1, 91.2) | 77.4 (74.2, 91.6) | 79.0 (67.7, 92.2) | 80.0 (66.8, 92.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 (23.2, 30.7) | 29.5 (25.4, 31.3) | 25.7 (23.6, 32.8) | 28.2 (24.5, 33.1) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.8 (86.2, 107) | 98.0 (94.5, 105) | 93.0 (86.5, 105) | 99.5 (91.2, 106) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 124 (110, 140) | 128 (122, 134) | 126 (115, 132) | 120 (114, 135) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.5 (70.2, 90.0) | 88.0 (78.2, 92.0) | 82.5 (77.5, 87.8) | 82.5 (77.8, 86.0) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) (74–100 a) | 89.5 (86.2, 94.0) | 94.0 (83.8, 95.8) | 90.0 (82.0, 98.5) | 93.5 (85.5, 102) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) (150–220 a) | 208 (177, 229) | 196 (180, 221) | 204 (183, 236) | 216 (186, 236) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) (45–84 a) | 52.0 (44.5, 57.0) | 47.0 (42.0, 53.0) | 53.0 (45.0, 57.0) | 44.5 (42.5, 48.8) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) (65–160 a) | 130 (104, 154) | 120 (109, 139) | 116 (110, 152) | 144 (109, 160) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (50–200 a) | 106 (87.8, 158) | 160 (112, 166) | 119 (100, 161) | 132 (104, 200) |

| HbA1c (%) (4.6–5.8 a) | 5.20 (5.10, 5.43) | 5.20 (5.00, 5.20) | 5.40 (5.20, 5.65) | 5.20 (5.10, 5.60) |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Never | 8 (30.8) | 2 (20) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (20) |

| Occasionally | 8 (30.8) | 3 (30) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (40) |

| Weekly | 7 (26.9) | 3 (30) | 11 (42.3) | 2 (20) |

| Daily | 3 (11.5) | 2 (20) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (20) |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | 10.0 (8.00, 11.8) | 11.0 (9.50, 12.0) | 10.5 (8.25, 12.8) | 11.0 (7.50, 12.0) |

| Low risk of suicide (0–8) | 9 (34.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (26.9) | 3 (30) |

| High risk of suicide (9–20) | 17 (65.4) | 10 (100) | 19 (73.1) | 7 (70) |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 14.5 (11.2, 19.0) | 12.5 (9.25, 13.8) | 14.0 (12.0, 19.8) | 15.0 (12.2, 17.0) |

| Low self-esteem (0–14) | 13 (50) | 8 (80) | 14 (53.8) | 5 (50) |

| Normal esteem (15–30) | 13 (50) | 2 (20) | 12 (46.2) | 5 (50) |

| STAI | ||||

| STAI State | 76.0 (55.0, 89.0) | 78.5 (28.5, 88.0) | 75.0 (51.2, 83.8) | 77.5 (45.0, 88.0) |

| STAI Trait | 88.0 (65.0, 97.0) | 82.5 (38.8, 95.0) | 85.0 (66.2, 95.8) | 70.0 (62.5, 78.8) |

| Plutchik Impulsivity Scale | 19.5 (12.0, 24.8) | 16.0 (14.2, 18.5) | 16.5 (12.2, 26.8) | 17.5 (13.8, 23.8) |

| Low impulsivity (0–20) | 13 (50) | 9 (90) | 15 (57.7) | 6 (60) |

| High impulsivity (21–45) | 13 (50) | 1 (10) | 11 (42.3) | 4 (40) |

| WHODAS | ||||

| Understanding and communication | 33.3 (20.8, 54.2) | 33.3 (22.9, 43.7) | 31.2 (20.8, 40.6) | 40.8 (26.0, 47.9) |

| Mobility | 17.5 (5.00, 40.0) | 25.0 (11.2, 25.0) | 22.5 (6.25, 33.8) | 22.5 (11.2, 28.8) |

| Personal care | 12.5 (1.19, 25.0) | 12.5 (6.25, 23.4) | 6.25 (0.00, 23.4) | 12.5 (6.25, 18.2) |

| Relationships | 42.5 (15.0, 53.8) | 33.5 (20.0, 43.8) | 37.5 (20.0, 58.8) | 37.5 (20.0, 52.3) |

| Daily life activities | 37.5 (18.8, 46.9) | 34.4 (24.2, 46.9) | 40.6 (15.6, 50.0) | 32.8 (18.8, 40.6) |

| Participation in society | 46.9 (32.0, 55.4) | 39.1 (28.9, 49.2) | 40.6 (22.7, 46.9) | 42.2 (28.1, 43.8) |

| Total score | 88.3 (82.7, 90.4) | 87.1 (85.8, 90.4) | 87.1 (82.7, 90.4) | 88.1 (83.5, 90.4) |

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||

| Physical Health | 13.0 (13.0, 25.0) | 19.0 (14.5, 19.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 25.0) | 13.0 (13.0, 19.0) |

| Psychological | 13.0 (6.00, 28.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 23.5) | 19.0 (6.00, 31.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 19.0) |

| Social relationships | 56.5 (31.0, 79.5) | 69.0 (50.0, 69.0) | 69.0 (44.0, 75.0) | 69.0 (51.5, 75.0) |

| Environment | 19.0 (13.0, 19.0) | 13.0 (13.0, 19.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 25.0) | 16.0 (13.0, 19.0) |

| Cliff’s Delta (95% CI) | Mean Difference b (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | −0.06 | (−0.45, 0.35) | −0.95 | (−4.02, 2.11) |

| IMC (kg/m2) | −0.07 | (−0.46, 0.34) | −0.42 | (−1.53, 0.69) |

| Waist circumference | 0.12 | (−0.28, 0.48) | 0.45 | (−3.48, 4.38) |

| SBP (mmHg) | −0.05 | (−0.44, 0.34) | −0.59 | (−9.34, 8.17) |

| DBP (mmHg) | −0.26 | (−0.62, 0.19) | −3.61 | (−11.8, 4.57) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 0.18 | (−0.25, 0.55) | 0.93 | (−10.6, 12.4) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.39 | (−0.09, 0.73) | 13.96 | (−1.99, 29.9) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.28 | (−0.26, 0.68) | 3.55 | (−1.62, 8.72) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.45 | (−0.03, 0.76) | 15.11 | (0.75, 29.5) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.00 | (−0.44, 0.44) | 1.21 | (−26.5, 28.9) |

| HbA1c (%) | −0.26 | (−0.69, 0.31) | −0.10 | (−0.93, 0.72) |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | −0.39 | (−0.69, 0.02) | −1.27 | (−3.18, 0.65) |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | −0.20 | (−0.61, 0.29) | −1.41 | (−4.79, 1.98) |

| STAI State | 0.15 | (−0.26, 0.52) | 4.97 | (−9.61, 19.6) |

| STAI Trait | −0.03 | (−0.49, 0.44) | 1.07 | (−12.1, 14.2) |

| Plutchik Impulsivity Scale | 0.32 | (−0.12, 0.66) | 2.28 | (−0.93, 5.50) |

| WHODAS | ||||

| Understanding and communication | 0.34 | (−0.15, 0.69) | 5.66 | (−2.64, 14.0) |

| Mobility | −0.02 | (−0.43, 0.39) | 0.68 | (−7.49, 8.84) |

| Personal care | 0.23 | (−0.19, 0.58) | 1.67 | (−11.8, 15.2) |

| Relations | 0.12 | (−0.33, 0.53) | 2.17 | (−9.74, 14.1) |

| Daily life activities | 0.09 | (−0.36, 0.51) | −0.44 | (−10.7, 9.83) |

| Participation in society | 0.27 | (−0.17, 0.62) | 6.29 | (−1.70, 14.3) |

| Total score | 0.35 | (−0.08, 0.67) | 1.81 | (−1.81, 5.42) |

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||

| Physical Health | 0.33 | (−0.06, 0.64) | 5.73 | (−0.19, 11.7) |

| Psychological | 0.50 | (0.13, 0.74) | 5.48 | (0.43, 10.5) |

| Social relationships | 0.07 | (−0.35, 0.47) | 1.32 | (−14.7, 17.3) |

| Environment | 0.04 | (−0.36, 0.42) | −2.99 | (−9.94, 3.96) |

| 6-Month Assessment | 12-Month Assessment | 2–3 Years Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 10 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 9 | Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 9 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 7 | Adventure Therapy (AT) N = 18 | Treatment as Usual (TAU) N = 4 | |

| Weight (kg) | 85.7 (71.7, 93.4) | 81.8 (62.2, 89.5) | 82.9 (68.2, 91.5) | 73.5 (62.5, 81.7) | 81.5 (71.2, 94.5) | 99.0 (89.4, 105) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7 (25.0, 32.8) | 27.0 (24.3, 31.2) | 28.0 (23.9, 30.3) | 25.4 (23.7, 28.6) | 27.9 (25.0, 30.9) | 33.4 (30.0, 36.5) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100 (89.2, 112) | 96.0 (85.0, 98.5) | 96.0 (86.0, 104) | 94.0 (83.2, 96.8) | 99.5 (91.8, 106) | 109 (98.8, 119) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 132 (128, 138) | 119 (112, 126) | 126 (120, 130) | 110 (106, 114) | 134 (121, 143) | 142 (138, 146) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 84.0 (80.2, 88.8) | 73.0 (70.0, 80.0) | 83.0 (76.0, 84.0) | 71.0 (65.0, 77.5) | 87.0 (82.2, 93.8) | 93.0 (87.2, 98.8) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 88.0 (79.0, 89.0) | 87.0 (84.8, 93.8) | 82.0 (81.0, 85.0) | 82.0 (78.2, 86.5) | 95.0 (87.2, 106) | 97.0 (90.8, 108) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 209 (201, 211) | 202 (186, 229) | 217 (200, 236) | 201 (189, 234) | 205 (188, 217) | 199 (196, 212) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 62.0 (45.0, 64.0) | 49.5 (43.0, 54.2) | 53.5 (48.5, 62.0) | 51.0 (44.8, 55.0) | 54.0 (45.5, 58.0) | 45.5 (43.5, 47.2) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 138 (126, 160) | 134 (120, 155) | 150 (135, 177) | 127 (117, 153) | 121 (106, 140) | 130 (127, 141) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 96.0 (81.0, 147) | 125 (74.8, 142) | 95.0 (72.0, 138) | 151 (116, 158) | 114 (77.0, 139) | 138 (121, 151) |

| HbA1c (%) (4.6–5.8 a) | 5.40 (5.20, 5.40) | 5.20 (5.07, 5.38) | 5.30 (5.25, 5.45) | 5.10 (5.00, 5.40) | 5.40 (5.15, 5.53) | 5.40 (5.00, 5.60) |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Never | 1 (10) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0) |

| Occasionally | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (38.9) | 0 (0) |

| Weekly | 6 (60) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (22.2) | 3 (75) |

| Daily | 3 (30) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (25) |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | 10.0 (8.25, 11.8) | 12.0 (10.0, 13.0) | 11.0 (9.00, 13.0) | 13.0 (10.5, 13.0) | 11.0 (8.00, 12.0) | 12.0 (10.2, 13.0) |

| Low risk of suicide (0–8) | 3 (30) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (25) |

| High risk of suicide (9–20) | 7 (70) | 8 (88.9) | 8 (88.9) | 7 (100) | 12 (66.7) | 3 (75) |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 12.5 (11.0, 14.8) | 15.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 15.0 (13.0, 16.0) | 15.0 (13.5, 18.0) | 13.0 (11.0, 14.0) | 13.0 (11.8, 14.5) |

| Low self-esteem (0–14) | 7 (70) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (42.9) | 15 (83.3) | 3 (75) |

| Normal esteem (15–30) | 3 (30) | 5 (55.6) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (25) |

| STAI | ||||||

| STAI State | 70.0 (37.5, 85.0) | 55.0 (40.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (45.0, 83.0) | 75.0 (57.5, 82.0) | 78.5 (43.8, 85.0) | 32.5 (12.2, 58.8) |

| STAI Trait | 72.5 (36.2, 95.0) | 77.0 (65.0, 85.0) | 65.0 (45.0, 89.0) | 60.0 (56.5, 90.0) | 80.0 (46.2, 95.0) | 52.5 (20.0, 81.2) |

| Plutchik Impulsivity Scale | 11.5 (10.0, 20.8) | 16.0 (13.0, 19.0) | 14.0 (11.0, 23.0) | 20.0 (14.0, 21.5) | 17.0 (11.0, 22.0) | 16.5 (13.0, 19.0) |

| Low impulsivity (0–20) | 7 (70) | 7 (77.8) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (42.9) | 11 (61.1) | 4 (100) |

| High impulsivity (21–45) | 3 (30) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (57.1) | 7 (38.9) | 0 (0) |

| WHODAS | ||||||

| Understanding and communication | 10.4 (8.33, 29.2) | 29.2 (16.7, 37.5) | 20.8 (12.5, 41.2) | 33.3 (20.8, 43.8) | 31.2 (16.7, 39.6) | 10.4 (3.13, 21.9) |

| Mobility | 15.0 (2.50, 36.2) | 20.0 (10.0, 40.0) | 10.0 (5.00, 15.0) | 20.0 (12.5, 35.0) | 15.0 (5.00, 37.5) | 7.50 (3.75, 16.2) |

| Personal care | 15.6 (1.56, 35.9) | 6.25 (0.00, 18.8) | 6.25 (0.00, 12.5) | 6.25 (6.25, 18.8) | 15.6 (0.00, 25.0) | 0.00 (0.00, 3.12) |

| Relationships | 25.0 (16.2, 30.0) | 20.0 (15.0, 35.0) | 20.0 (15.0, 30.0) | 30.0 (22.5, 45.0) | 35.0 (20.0, 53.8) | 32.5 (17.5, 45.0) |

| Daily life activities | 32.8 (20.3, 49.2) | 37.5 (18.8, 40.6) | 18.8 (18.8, 43.7) | 37.5 (28.1, 42.2) | 42.2 (28.1, 55.5) | 17.2 (10.9, 22.7) |

| Participation in society | 26.6 (14.1, 46.9) | 34.4 (31.2, 40.6) | 25.0 (21.9, 40.6) | 34.4 (32.8, 48.4) | 35.9 (19.5, 48.4) | 35.9 (26.6, 44.5) |

| Total score | 82.1 (73.9, 88.3) | 85.8 (78.4, 90.4) | 78.4 (72.3, 82.7) | 85.8 (85.8, 89.4) | 85.8 (79.5, 93.6) | 77.5 (72.3, 83.5) |

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||||

| Physical Health | 19.0 (14.5, 28.0) | 13.0 (6.00, 19.0) | 25.0 (13.0, 31.0) | 13.0 (13.0, 28.0) | 19.0 (7.75, 23.5) | 19.0 (11.2, 29.8) |

| Psychological | 22.0 (13.0, 31.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 31.0) | 19.0 (19.0, 25.0) | 13.0 (13.0, 25.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 29.5) | 25.0 (22.0, 29.8) |

| Social relationships | 69.0 (54.8, 93.8) | 69.0 (50.0, 81.0) | 69.0 (50.0, 81.0) | 69.0 (56.5, 97.0) | 72.0 (44.0, 79.5) | 56.5 (33.0, 76.8) |

| Environment | 22.0 (19.0, 25.0) | 19.0 (13.0, 19.0) | 19.0 (19.0, 25.0) | 19.0 (9.50, 22.0) | 19.0 (14.5, 25.0) | 19.0 (11.2, 25.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabarda-Blasco, A.; Elias, A.; Mendo-Cullell, M.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Forné, C.; Fernandez-Oñate, D.; Bossa, L.; Torrent, A.; Gallart-Palau, X.; Batalla, I. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030236

Gabarda-Blasco A, Elias A, Mendo-Cullell M, Arenas-Pijoan L, Forné C, Fernandez-Oñate D, Bossa L, Torrent A, Gallart-Palau X, Batalla I. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(3):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030236

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabarda-Blasco, Alba, Aina Elias, Mariona Mendo-Cullell, Laura Arenas-Pijoan, Carles Forné, David Fernandez-Oñate, Laura Bossa, Aurora Torrent, Xavier Gallart-Palau, and Iolanda Batalla. 2024. "Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial" Brain Sciences 14, no. 3: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030236

APA StyleGabarda-Blasco, A., Elias, A., Mendo-Cullell, M., Arenas-Pijoan, L., Forné, C., Fernandez-Oñate, D., Bossa, L., Torrent, A., Gallart-Palau, X., & Batalla, I. (2024). Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of an Adventure Therapy Programme on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain Sciences, 14(3), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030236