Sex Differences in Conversion Risk from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Explainable Machine Learning Study with Random Survival Forests and SHAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Preparation

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Random Survival Forests

2.4. Machine Learning Analysis

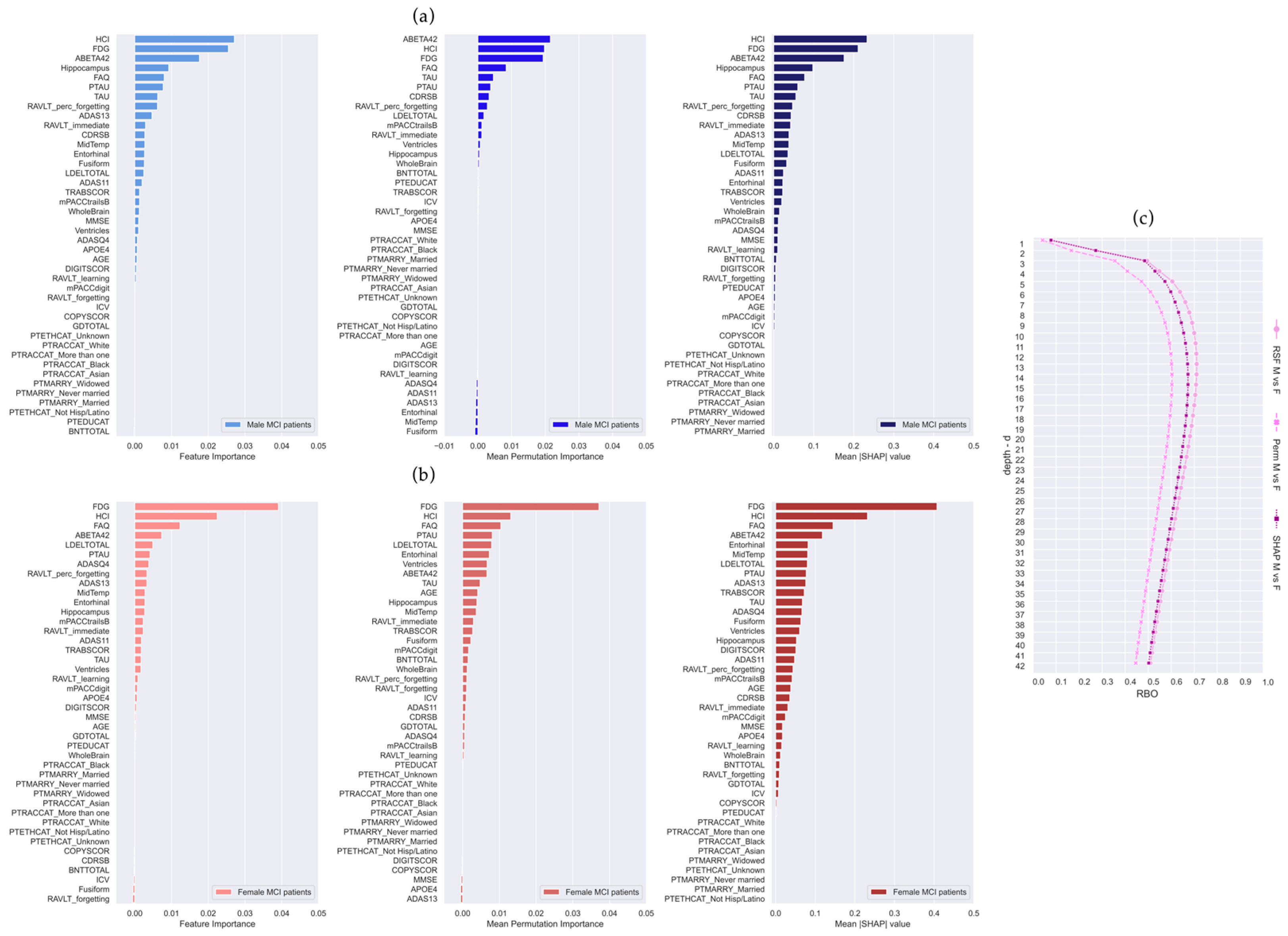

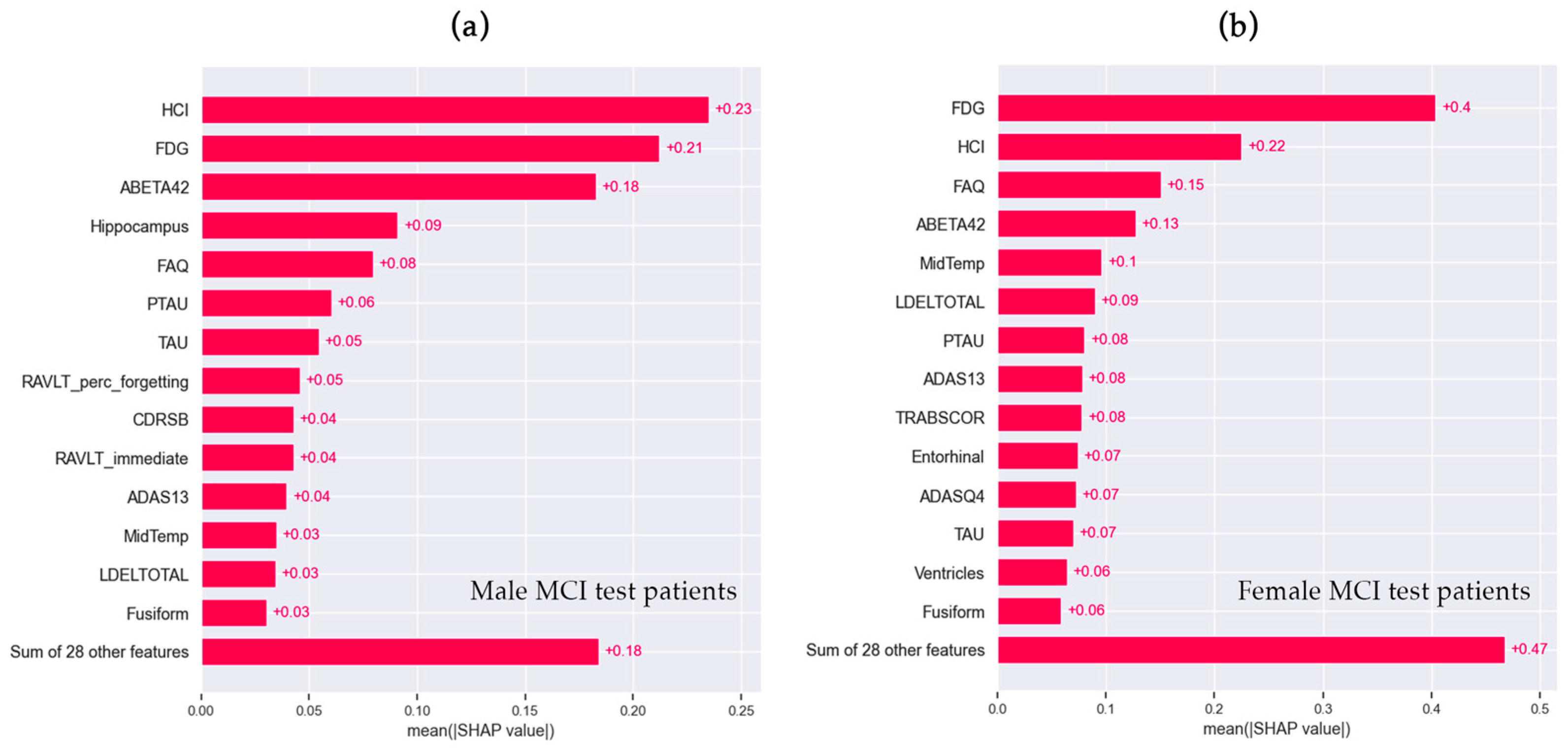

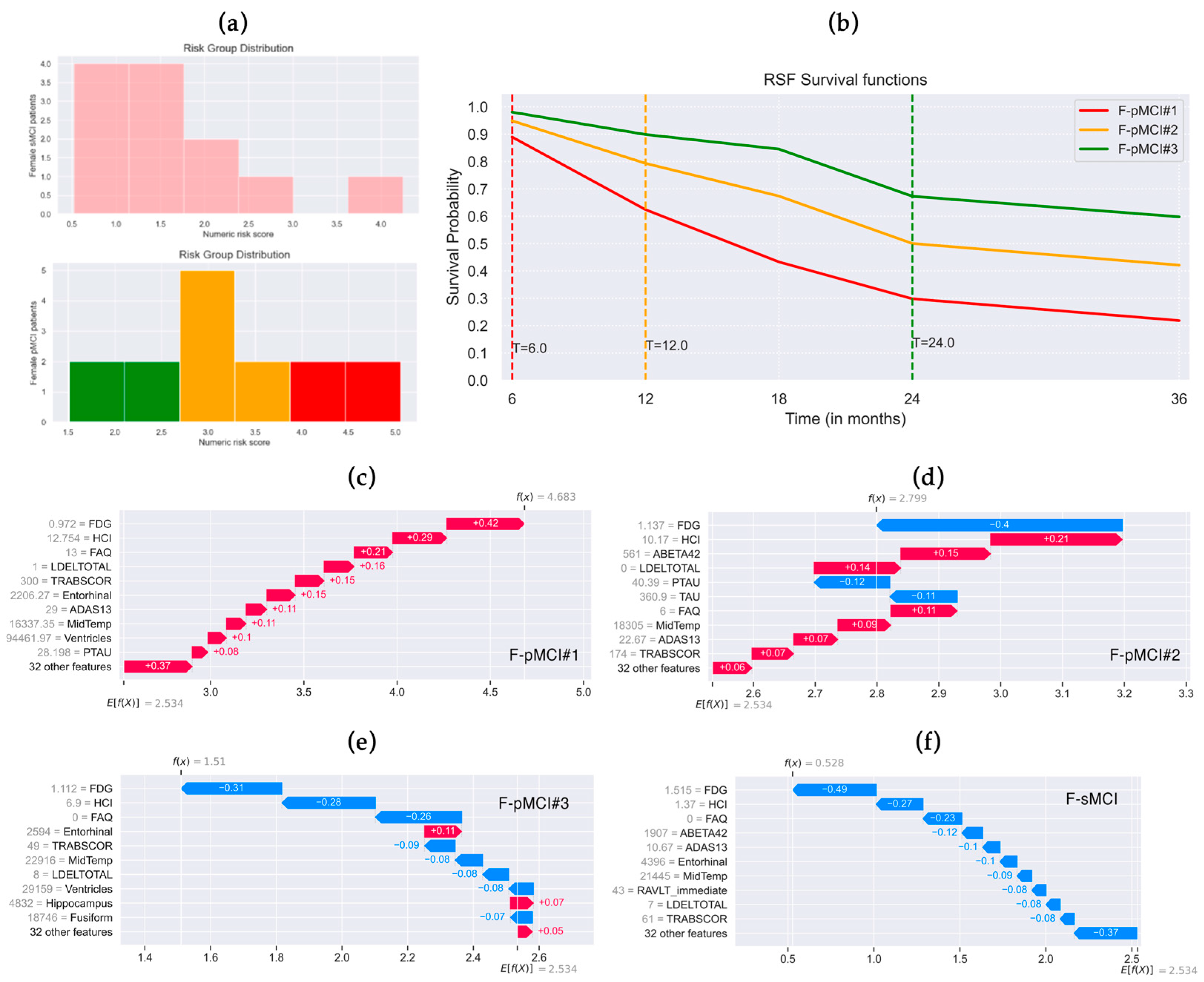

2.4.1. Global Explanation

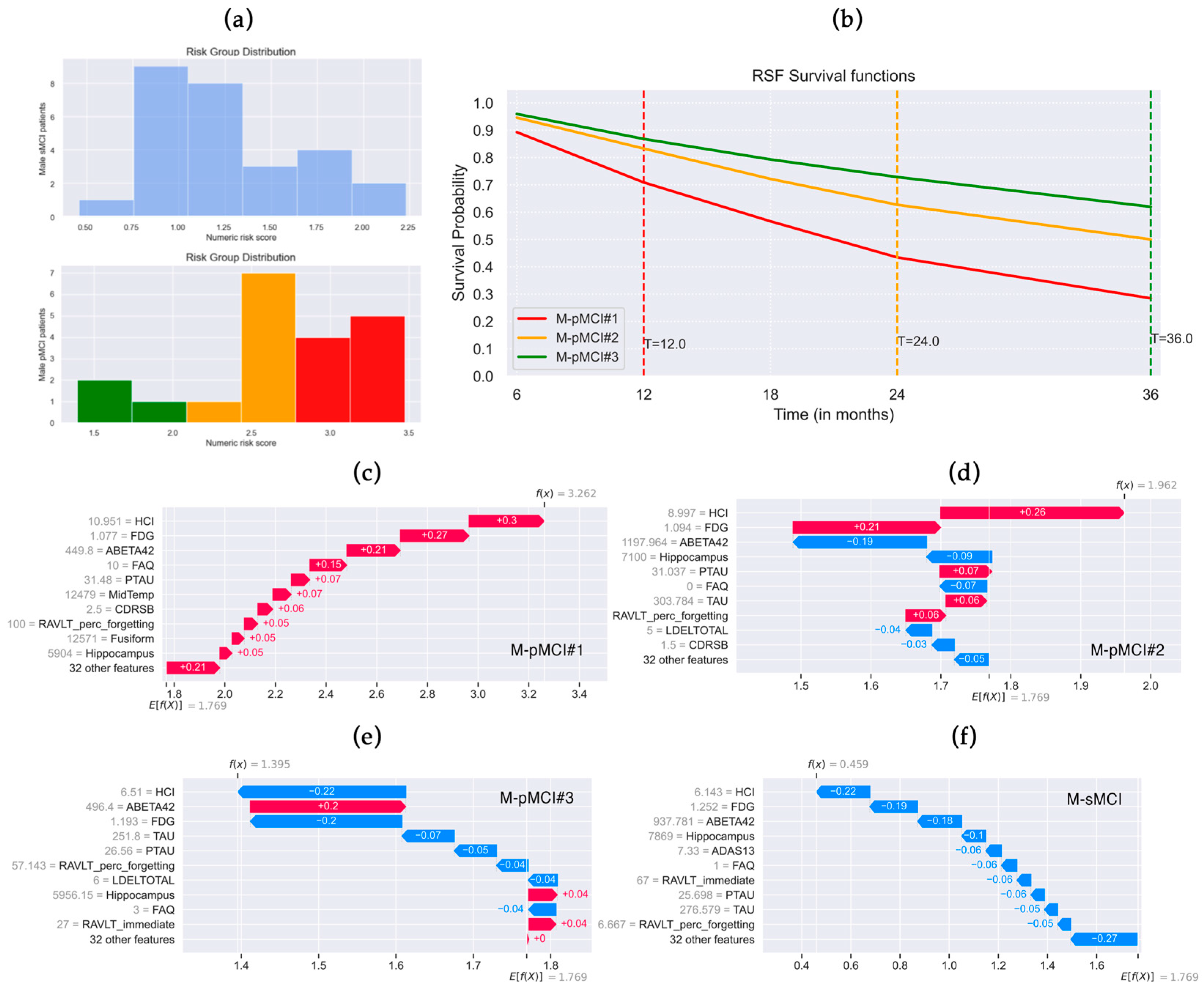

2.4.2. Local Explanation

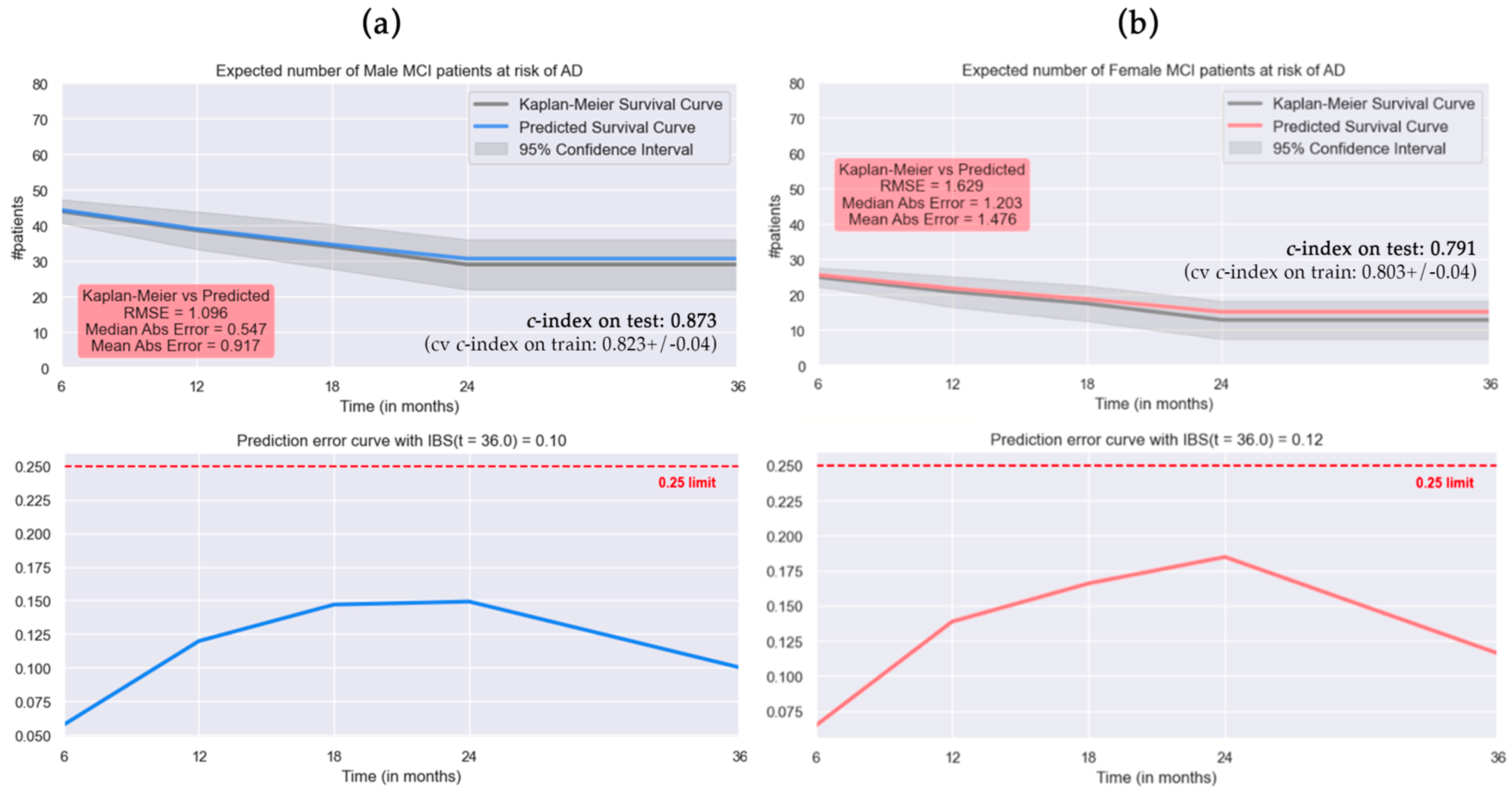

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Biomarker: APOE4 allele genotype, i.e., presence of APOE gene that makes the APOE4 protein, associated with late-stage AD [56].

- Clinical scales:

- ○

- Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDRSB) is the sum score of the six domains used to accurately stage the severity of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and Mild Cognitive Impairment [57].

- ○

- Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ): an informant-based clinician-administered questionnaire that assesses the functional daily living impairment in dementia [47]. The total score ranges from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 30. A recommended cut-off of 9, indicating dependence on the caregiver in three or more activities, is suggested to identify impaired function and potential cognitive impairment [47].

- Neuropsychological assessment:

- ○

- Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS), items 11 and 13, and delayed word recall (Q4) for assessing the memory, language, and praxis domains with 11 tasks, both subject-completed tests and observer-based assessments [58]. Total scores can range from 0 to 70, and higher scores (≥18) suggest more significant cognitive impairment [59].

- ○

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): 30 questions on orientation, short-term memory retention, attention, short-term recall, and language to measure cognitive impairment and stage of the severity level [60]. The MMSE scores range from 0 to 30, and lower scores suggest a greater level of cognitive impairment [61].

- ○

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) [62] is a tool designed for assessing various aspects of cognitive function, including episodic declarative memory, immediate memory span, verbal learning, susceptibility to proactive and retroactive interferences, retention of information, and abilities related to recall and memory recognition. In detail, RAVLT_immediate evaluates immediate memory span (the sum of scores from the first five trials, i.e., Trials 1 to 5), RAVLT_learning measures learning ability and memorization of new information within a given time period (the score of Trial 5 minus the score of Trial 1), RAVLT_forgetting (the score of Trial 5 minus the score of the delayed recall) and RAVLT_percent_forgetting (RAVLT Forgetting divided by the score of Trial 5) estimate the amount of forgotten information [48].

- ○

- The total delayed recall score of the Logic Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (LDELTOTAL), which assesses verbal memory. The correct responses to the items are summed, and the maximum score assigned is 25, for both immediate and delayed recall. Higher scores reflect greater verbal memory ability [50].

- ○

- Digit Symbol Substitution (DIGITSCOR) to evaluate attention, processing speed, and executive function [63]. The score is given by the total number of correct symbols executed within the allotted time.

- ○

- ○

- ADNI-modified Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) with Digit Symbol Substitution (mPACCdigit), and with Trails B (mPACCtrailsB) that measure the first signs of cognitive decline [65].

- ○

- Geriatric Depression Scale (GDTOTAL) to identify depression in elderly subjects [66]. A higher score on the GDS indicates a higher level of depressive symptoms.

- ○

- ○

- Boston Naming Test (BNTTOTAL) assesses naming ability using 30 items [66].

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker: Aβ1–42 (ABETA42), total tau (TAU), phosphorylated tau (PTAU) concentrations [68].

- Neuroimaging measures: MRI volumes of the ventricles, hippocampus, whole brain, entorhinal cortex, fusiform, middle temporal gyrus (MidTemp), and total intracranial volume (ICV), calculated with Freesurfer [69]; average fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography of angular, temporal, and posterior cingulate (FDG) [70]; hypometabolic convergence index (HCI) [71], an FDG-PET index that provides a single measurement of cerebral hypometabolism compared to the AD patients group.

References

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.; Kang, H.S.; Lim, S.W.; Myung, W.; Lee, Y.; Hong, C.H.; Choi, S.H.; Na, D.L.; et al. Gender differences in risk factors for transition from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A CREDOS study. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, M.T.; Iulita, M.F.; Cavedo, E.; Chiesa, P.A.; Schumacher Dimech, A.; Santuccione Chadha, A.; Baracchi, F.; Girouard, H.; Misoch, S.; Giacobini, E.; et al. Sex differences in Alzheimer disease—The gateway to precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, D.; Shpanskaya, K.; Lucas, J.E.; Petrella, J.R.; Saykin, A.J.; Tanzi, R.E.; Samatova, N.F.; Doraiswamy, P.M. Sex Differences in Cognitive Decline in Subjects with High Likelihood of Mild Cognitive Impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezuk, C.; Khan, M.; Callahan, B.L.; Ramirez, J.; Black, S.E.; Zakzanis, K.K.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sex differences in risk factors that predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2023, 29, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.L.; Hu, T.; Fava, N.M.; Li, T.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Schuldiner, K.L.; Burgess, A.; Laird, A. Sex differences in the development of mild cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer’s disease as predicted by hippocampal volume or white matter hyperintensities. J. Women Aging 2019, 31, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, L.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, H.; Patel, J. Dump the “dimorphism”: Comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male-female differences beyond size. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.A.; Choudhury, K.R.; Rathakrishnan, B.G.; Marks, D.M.; Petrella, J.R.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Marked gender differences in progression of mild cognitive impairment over 8 years. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 1, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artero, S.; Ancelin, M.-L.; Portet, F.; Dupuy, A.; Berr, C.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Tzourio, C.; Rouaud, O.; Poncet, M.; Pasquier, F. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia are gender specific. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, T.M. Subjective cognitive decline, APOE e4 allele, and the risk of neurocognitive disorders: Age- and sex-stratified cohort study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundermann, E.E.; Biegon, A.; Rubin, L.H.; Lipton, R.B.; Mowrey, W.; Landau, S.; Maki, P.M.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Better verbal memory in women than men in MCI despite similar levels of hippocampal atrophy. Neurology 2016, 86, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundermann, E.E.; Maki, P.; Biegon, A.; Lipton, R.B.; Mielke, M.M.; Machulda, M.; Bondi, M.W.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sex-specific norms for verbal memory tests may improve diagnostic accuracy of amnestic MCI. Neurology 2019, 93, e1881–e1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.C.; Lim, H.; Byun, M.S.; Yi, D.; Byeon, G.; Jung, G.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, D.Y.; Han, S.H.; Mook-Jung, I. Sex differences in the progression of glucose metabolism dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, A.; Cuesta, P.; Marcos, A.; Montenegro-Peña, M.; Yus, M.; Rodríguez-Rojo, I.C.; Bruña, R.; Maestú, F.; López, M.E. Sex differences in the progression to Alzheimer’s disease: A combination of functional and structural markers. GeroScience 2023, 46, 2619–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, L.E.; Scherr, P.A.; McCann, J.J.; Beckett, L.A.; Evans, D.A. Is the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease greater for women than for men? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.W.; Bennett, D.A.; Dong, H. Sexual dimorphism in predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 70, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwaran, H.; Kogalur, U.B. Consistency of Random Survival Forests. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2010, 80, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwaran, H.; Kogalur, U.B.; Blackstone, E.H.; Lauer, M.S. Random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2008, 2, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, A.; Cerasa, A.; Quattrone, A. Random Forest Algorithm for the Classification of Neuroimaging Data in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.O.; Crnovrsanin, N.; Wirsik, N.M.; Nienhuser, H.; Peters, L.; Popp, F.; Schulze, A.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Stich, B.P.; Buchler, M.W.; et al. Machine learning for optimized individual survival prediction in resectable upper gastrointestinal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 149, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; You, W.; Pan, K.; Li, W. Random survival forest: Applying machine learning algorithm in survival analysis of biomedical data. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 55, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sarica, A.; Aracri, F.; Bianco, M.G.; Vaccaro, M.G.; Quattrone, A.; Quattrone, A. Conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison of tree-based Machine Learning algorithms for Survival Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Brain Informatics, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1–3 August 2023; pp. 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sarica, A.; Aracri, F.; Bianco, M.G.; Arcuri, F.; Quattrone, A.; Quattrone, A.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Explainability of random survival forests in predicting conversion risk from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Inform. 2023, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moncada-Torres, A.; van Maaren, M.C.; Hendriks, M.P.; Siesling, S.; Geleijnse, G. Explainable machine learning can outperform Cox regression predictions and provide insights in breast cancer survival. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, W.; Moffat, A.; Zobel, J. A similarity measure for indefinite rankings. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. TOIS 2010, 28, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, A.; Quattrone, A.; Quattrone, A. Introducing the Rank-Biased Overlap as Similarity Measure for Feature Importance in Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study on Parkinson’s Disease. In Proceedings of the Brain Informatics: 15th International Conference, BI 2022, Padua, Italy, 15–17 July 2022; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sarica, A.; Di Fatta, G.; Cannataro, M. K-Surfer: A KNIME extension for the management and analysis of human brain MRI FreeSurfer/FSL data. In Proceedings of the Brain Informatics and Health: International Conference, BIH 2014, Warsaw, Poland, 11–14 August 2014; pp. 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on categorical data for neural networks. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, A.; Chen, E.; Sowmya, A.; Sachdev, P.; Kochan, N.A.; Trollor, J.; Brodaty, H. A comparison of machine learning methods for survival analysis of high-dimensional clinical data for dementia prediction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stekhoven, D.J.; Buhlmann, P. MissForest--non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aracri, F.; Bianco, M.G.; Quattrone, A.; Sarica, A. Imputation of missing clinical, cognitive and neuroimaging data of Dementia using missForest, a Random Forest based algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 36th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), L’Aquila, Italy, 22–24 June 2023; pp. 684–688. [Google Scholar]

- Aracri, F.; Bianco, M.G.; Quattrone, A.; Sarica, A. Impact of imputation methods on supervised classification: A multiclass study on patients with parkinson’s disease and subjects with scans without evidence of dopaminergic deficit. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Workshop on Biomedical Applications, Technologies and Sensors (BATS), Catanzaro, Italy, 28–29 September 2023; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Sanchez, J.; Trevino, V.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Farber, J.; Tamez-Peña, J. Exploring survival models associated with MCI to AD conversion: A machine learning approach. bioRxiv 2019, 836510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Ishida, M.; Naito, J.; Nagai, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Onoda, K.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease using deep survival analysis of MRI images. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabnahrazam, G.; Ma, D.; Beaulac, C.; Lee, S.; Popuri, K.; Lee, H.; Cao, J.; Galvin, J.E.; Wang, L.; Beg, M.F.; et al. Predicting time-to-conversion for dementia of Alzheimer’s type using multi-modal deep survival analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 2023, 121, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musto, H.; Stamate, D.; Pu, I.; Stahl, D. Predicting Alzheimers Disease Diagnosis Risk over Time with Survival Machine Learning on the ADNI Cohort. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10326. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Asken, B.; Armstrong, M.J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. Predicting Progression to Clinical Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia Using the Random Survival Forest. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.N.; Dankowski, T.; Ziegler, A. Unbiased split variable selection for random survival forests using maximally selected rank statistics. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, H.; Cai, T.; Pencina, M.J.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Wei, L.-J. On the C-statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Cook, N.R.; Gerds, T.; Gonen, M.; Obuchowski, N.; Pencina, M.J.; Kattan, M.W. Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, V.; Bellamy, R.K.; Chen, P.-Y.; Dhurandhar, A.; Hind, M.; Hoffman, S.C.; Houde, S.; Liao, Q.V.; Luss, R.; Mojsilović, A. AI Explainability 360 Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM India Joint International Conference on Data Science & Management of Data (8th ACM IKDD CODS & 26th COMAD), Bangalore, India, 2–4 January 2021; pp. 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Malpetti, M.; Ballarini, T.; Presotto, L.; Garibotto, V.; Tettamanti, M.; Perani, D.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Database; Network for Efficiency and Standardization of Dementia Diagnosis (NEST-DD) Database. Gender differences in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s Dementia: A (18) F-FDG-PET study of brain and cognitive reserve. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 4212–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, R.I.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Harrah, C.H., Jr.; Chance, J.M.; Filos, S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J. Gerontol. 1982, 37, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, A.; Vasta, R.; Novellino, F.; Vaccaro, M.G.; Cerasa, A.; Quattrone, A.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. MRI asymmetry index of hippocampal subfields increases through the continuum from the mild cognitive impairment to the Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Zhang, Z.; Watson, D.R.; Yu, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Qian, Y. Absent gender differences of hippocampal atrophy in amnestic type mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 450, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognani, S.A.P.; Miranda, M.C.; Martins, M.; Rzezak, P.; Bueno, O.F.A.; de Camargo, C.H.P.; Pompeia, S. Development of alternative versions of the Logical Memory subtest of the WMS-R for use in Brazil. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2015, 9, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowie, C.R.; Harvey, P.D. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2277–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalev, M.S.; Utkin, L.V.; Kasimov, E.M. SurvLIME: A method for explaining machine learning survival models. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 203, 106164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyziński, M.; Spytek, M.; Baniecki, H.; Biecek, P. SurvSHAP (t): Time-dependent explanations of machine learning survival models. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 262, 110234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.B.; DeRosa, J.T.; Moon, M.P.; Strobino, K.; DeCarli, C.; Cheung, Y.K.; Assuras, S.; Levin, B.; Stern, Y.; Sun, X. Race/ethnic disparities in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: The Northern Manhattan Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 80, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra Bautista, Y.J.; Messeha, S.S.; Theran, C.; Aló, R.; Yedjou, C.; Adankai, V.; Babatunde, S.; Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction of Longitudinal Evolution. Marital Status of Never Married with Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test Cognition Performance Is Associated with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; DeStafano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Lacritz, L.H.; Hall, J.; Waring, S.C.; Chan, W.; Khodr, Z.G.; Massman, P.J.; Hobson, V.; Cullum, C.M. Validation of the new interpretive guidelines for the clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes score in the national Alzheimer’s coordinating center database. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, M.; Rouleaux, N.; Caldirola, D.; Loewenstein, D.; Schruers, K.; Perna, G.; Dumontier, M.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. A Novel Ensemble-Based Machine Learning Algorithm to Predict the Conversion From Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease Using Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Clinical Information, and Neuropsychological Measures. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Fay, S.; Gorman, M.; Carver, D.; Graham, J.E. The clinical meaningfulness of ADAS-Cog changes in Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil in an open-label trial. BMC Neurol. 2007, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.T.; Seward, K.; Patterson, A.; Melton, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Evaluation of Available Cognitive Tools Used to Measure Mild Cognitive Decline: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-González, A.; Kulisevsky, J.; Boltes, A.; Otermín, P.; García-Sánchez, C. Rey verbal learning test is a useful tool for differential diagnosis in the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease: Comparison with mild cognitive impairment and normal aging. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2003, 18, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, J. Digit Symbol Substitution Test: The Case for Sensitivity Over Specificity in Neuropsychological Testing. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Salmon, D.P.; Rentz, D.M.; Raman, R.; Thomas, R.G.; Weiner, M.; Aisen, P.S. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: Measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battista, P.; Salvatore, C.; Castiglioni, I. Optimizing Neuropsychological Assessments for Cognitive, Behavioral, and Functional Impairment Classification: A Machine Learning Study. Behav. Neurol. 2017, 2017, 1850909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, E.; Peters, R. Literature review of the Clock Drawing Test as a tool for cognitive screening. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 27, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.M.; Vanderstichele, H.; Knapik-Czajka, M.; Clark, C.M.; Aisen, P.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Blennow, K.; Soares, H.; Simon, A.; Lewczuk, P.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 65, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, A.M.; Fischl, B.; Sereno, M.I. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 1999, 9, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, S.M.; Harvey, D.; Madison, C.M.; Reiman, E.M.; Foster, N.L.; Aisen, P.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Shaw, L.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; et al. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2010, 75, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Ayutyanont, N.; Langbaum, J.B.; Fleisher, A.S.; Reschke, C.; Lee, W.; Liu, X.; Bandy, D.; Alexander, G.E.; Thompson, P.M.; et al. Characterizing Alzheimer’s disease using a hypometabolic convergence index. Neuroimage 2011, 56, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M (233) | F (132) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sMCI (136) | pMCI (97) | sMCI (62) | pMCI (70) | |

| Demographic: | ||||

| Age | 74.7 ± 7.3 | 74.6 ± 7.5 | 75.8 ± 7.6 | 74.6 ± 6.0 |

| Education level | 15 ± 3.3 | 15.4 ± 2.9 | 16.2 ± 2.6 | 16.1 ± 2.8 |

| Biomarker: | ||||

| APOE4 (0/1/2) | 82/42/12 | 38/43/16 | 28/26/8 | 16/43/11 |

| Clinical scale: | ||||

| CDRSB | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1.1 |

| FAQ | 2.3 ± 3.2 | 5.6 ± 5.3 | 2.8 ± 4.1 | 5.6 ± 4.5 |

| Neuropsychological assessment: | ||||

| ADAS11 | 10.5 ± 4.2 | 13.12 ± 3.8 | 10.5 ± 4.6 | 13.2 ± 4.5 |

| ADAS13 | 16.8 ± 6.0 | 21.3 ± 5.0 | 16.9 ± 6.7 | 21.1 ± 6.2 |

| ADASQ4 | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 7.13 ± 1.9 | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 7.1 ± 2.0 |

| MMSE | 27.3 ± 1.8 | 26.68 ± 1.7 | 27.2 ± 1.7 | 26.6 ± 1.8 |

| RAVLT_immediate | 33.1 ± 9.6 | 27.25 ± 6.9 | 33.1 ± 10.6 | 27.2 ± 6.2 |

| RAVLT_learning | 3.8 ± 2.3 | 2.74 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 3.0 ± 2.0 |

| RAVLT_forgetting | 4.5 ± 2.4 | 4.86 ± 2.09 | 4.5 ± 2.3 | 5.0 ± 2.2 |

| RAVLT_perc_forgetting | 59.9 ± 31.5 | 77.62 ± 27.6 | 63.8 ± 31.0 | 79.0 ± 28.5 |

| LDELTOTAL | 4.3 ± 2.7 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 3.3 ± 3.1 |

| DIGITSCOR | 38.9 ± 11.1 | 34.13 ± 11.2 | 37.0 ± 9.7 | 34.0 ± 10.5 |

| TRABSCOR | 116.4 ± 64.2 | 146.85 ± 79.9 | 125.6 ± 67.1 | 149.9 ± 80.2 |

| mPACCdigit | −3.9 ± 3.9 | −3.9 ± 4.8 | −3.8 ± 3.8 | −3.9 ± 4.9 |

| mPACCtrailsB | −3.8 ± 4.0 | −3.7 ± 4.8 | −3.8 ± 3.8 | −3.0 ± 4.8 |

| GDTOTAL | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.54 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.4 |

| COPYSCOR | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 0.6 |

| BNTTOTAL | 25.5 ± 4.0 | 24.55 ± 4.6 | 26.2 ± 3.2 | 25.7 ± 3.6 |

| CSF: | ||||

| ABETA42 | 1027.5 ± 398.4 | 676.7 ± 224.3 | 881.4 ± 364.2 | 708.8 ± 309.2 |

| TAU | 307.2 ± 89.4 | 316.43 ± 73.2 | 307.5 ± 110.9 | 331.0 ± 90.2 |

| PTAU | 30.4 ± 10.8 | 31.76 ± 8.0 | 31.2 ± 14.0 | 33.3 ± 10.8 |

| Neuroimaging: | ||||

| Ventricles | 41,196.5 ± 24,245.5 | 44,937.2 ± 18,888.8 | 48,192.5 ± 26,633.5 | 50,164.0 ± 27,112.5 |

| Hippocampus | 6699.8 ± 987.2 | 5862.6 ± 923.9 | 6452.7 ± 963.8 | 6092 ± 1095.6 |

| WholeBrain | 1,005,263.4 ± 106,966.9 | 973,259.03 ± 115,953.1 | 1,013,898.5 ± 100,967.5 | 990,467.4 ± 111,353.5 |

| Entorhinal | 3480.9 ± 711.5 | 2997.0 ± 698.9 | 3475.5 ± 707.2 | 3031.5 ± 723.4 |

| Fusiform | 16,831.29 ± 2179.3 | 15,618.0 ± 2409.4 | 16,947.7 ± 2161.6 | 15,884.9 ± 2393.1 |

| MidTemp | 19,134.46 ± 2554.2 | 17,311.45 ± 3127.2 | 19,604.9 ± 2652.1 | 17,911.5 ± 2708.5 |

| ICV | 1,562,645.6 ± 163,009.0 | 1,554,468.3 ± 170,366.0 | 1,609,215.3 ± 162,431.2 | 1,587,939.1 ± 176,315.7 |

| FDG | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.07 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| HCI | 7.1 ± 2.8 | 9.54 ± 2.5 | 7.1 ± 2.7 | 9.9 ± 2.9 |

| Occurrence of event (pMCI = 1) and censorship (sMCI = 0) per timepoint (in months): | ||||

| m06 | 17 | 14 | 3 | 8 |

| m12 | 12 | 27 | 5 | 20 |

| m18 | 14 | 20 | 7 | 15 |

| m24 | 21 | 18 | 10 | 18 |

| m36 | 72 | 18 | 37 | 8 |

| p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-sMCI vs. M-pMCI | F-sMCI vs. F-pMCI | M-sMCI vs. F-sMCI | M-pMCI vs. F-pMCI | |

| Demographic: | ||||

| Age | 0.95 a | 0.32 a | 0.35 a | 0.96 a |

| Education level | 0.27 a | 0.81 a | 0.006 a | 0.14 a |

| Biomarker: | ||||

| APOE4 (0/1/2) | 0.005 b | 0.02 b | 0.14 b | 0.58 b |

| Clinical scale: | ||||

| CDRSB | <0.001 c | 0.12 c | 0.11 c | 0.90 c |

| FAQ | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.34 c | 0.93 c |

| Neuropsychological assessment: | ||||

| ADAS11 | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.95 c | 0.93 c |

| ADAS13 | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.97 c | 0.78 c |

| ADASQ4 | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.67 c | 0.94 c |

| MMSE | 0.01 c | 0.03 c | 0.82 c | 0.76 c |

| RAVLT_immediate | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.87 c | 0.92 c |

| RAVLT_learning | <0.001 c | 0.03 c | 0.88 c | 0.46 c |

| RAVLT_forgetting | 0.24 c | 0.3 c | 0.82 c | 0.64 c |

| RAVLT_perc_forgetting | <0.001 c | 0.003 c | 0.41 c | 0.76 c |

| LDELTOTAL | <0.001 c | 0.004 c | 0.28 c | 0.28 c |

| DIGITSCOR | 0.001 c | 0.06 c | 0.31 c | 0.93 c |

| TRABSCOR | 0.001 c | 0.06 c | 0.43 c | 0.81 c |

| mPACCdigit | 0.94 c | 0.97 c | 0.86 c | 0.98 c |

| mPACCtrailsB | 0.89 c | 0.21 c | 0.89 c | 0.35 c |

| GDTOTAL | 0.77 c | 0.98 c | 0.85 c | 0.87 c |

| COPYSCOR | 0.03 c | 0.76 c | 0.72 c | 0.07 c |

| BNTTOTAL | 0.09 c | 0.33 c | 0.22 c | 0.07 c |

| CSF: | ||||

| ABETA42 | <0.001 c | 0.003 c | 0.015 c | 0.43 c |

| TAU | 0.41 c | 0.17 c | 0.97 c | 0.25 c |

| PTAU | 0.29 c | 0.32 c | 0.67 c | 0.29 c |

| Neuroimaging: | ||||

| Ventricles | 0.067 d | 0.11 d | 0.50 d | 0.33 d |

| Hippocampus | <0.001 d | 0.01 d | 0.053 d | 0.27 d |

| WholeBrain | 0.02 c | 0.10 c | 0.38 c | 0.32 c |

| Entorhinal | <0.001 d | <0.001 d | 0.75 d | 0.91 d |

| Fusiform | <0.001 d | 0.005 | 0.71 d | 0.96 d |

| MidTemp | <0.001 d | 0.001 d | 0.54 d | 0.47 d |

| ICV | 0.70 c | 0.45 c | 0.063 c | 0.22 c |

| FDG | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.66 c | 0.94 c |

| HCI | <0.001 c | <0.001 c | 0.96 c | 0.34 c |

| Optimal Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperparameter | Parameter Distribution | M-RSF | F-RSF |

| max_depth | integer from a reciprocal continuous random distribution in range (5, 50) | 26 | 42 |

| min_node_size | integer from a reciprocal continuous random distribution in range (1, 40) | 34 | 19 |

| max_features | [‘all’, ‘sqrt’, ‘log2’] | ‘sqrt’ | ‘sqrt’ |

| sample_size_pct | [0.60, 0.70, 0.80, 0.90] | 0.70 | 0.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarica, A.; Pelagi, A.; Aracri, F.; Arcuri, F.; Quattrone, A.; Quattrone, A.; for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sex Differences in Conversion Risk from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Explainable Machine Learning Study with Random Survival Forests and SHAP. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030201

Sarica A, Pelagi A, Aracri F, Arcuri F, Quattrone A, Quattrone A, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sex Differences in Conversion Risk from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Explainable Machine Learning Study with Random Survival Forests and SHAP. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(3):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030201

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarica, Alessia, Assunta Pelagi, Federica Aracri, Fulvia Arcuri, Aldo Quattrone, Andrea Quattrone, and for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. 2024. "Sex Differences in Conversion Risk from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Explainable Machine Learning Study with Random Survival Forests and SHAP" Brain Sciences 14, no. 3: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030201

APA StyleSarica, A., Pelagi, A., Aracri, F., Arcuri, F., Quattrone, A., Quattrone, A., & for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2024). Sex Differences in Conversion Risk from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Explainable Machine Learning Study with Random Survival Forests and SHAP. Brain Sciences, 14(3), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030201