Abstract

Each year, 275 million children worldwide are exposed to domestic violence (DV) and suffer negative mental and physical health consequences; however, only a small proportion receive assistance. Pediatricians and child psychiatrists can play a central role in identifying threatened children. We reviewed experiences of DV screening in pediatric and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) to understand its feasibility and provide clues for its implementation. We performed bibliographic research using the Sapienza Library System, PubMed, and the following databases: MEDLINE, American Psychological Association PsycArticles, American Psychological Association PsycInfo, ScienceDirect, and Scopus. We considered a 20-year interval when selecting the articles and we included studies published in English between January 2000 and March 2021. A total of 23 out of 2335 studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. We found that the prevalence of disclosed DV ranged from 4.2% to 48%, with most prevalence estimates between 10% and 20%. Disclosure increases with a detection plan, which is mostly welcomed by mothers (70–80% acceptance rates). Written tools were used in 55% of studies, oral interviews in 40%, and computer instruments in 20%. Mixed forms were used in three studies (15%). The most used and effective tool appeared to be the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (30% of studies). For young children, parental reports are advisable and written instruments are the first preference; interviews can be conducted with older children. Our research pointed out that the current literature does not provide practical clinical clues on facilitating the disclosure in pediatric clinics and CAMHS. Further studies are needed on the inpatient population and in the field of children psychiatry.

1. Introduction

The terms intimate partner violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV) are often used to define the same phenomenon, referring to both acts and threats of physical, sexual, psychological and emotional violence, perpetrated by a current or former partner or spouse [1]. Usually, the concept of DV is related to IPV, especially in the American and North Europe contexts, but sometimes, it includes all types of violence that occur within families [2].

DV is a common phenomenon; according to the report by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013, data on women report a lifetime DV prevalence of 30% worldwide [3], with a higher risk of DV exposure in pregnant mothers and younger children [4]. Regarding the American population, the number of victims of DV is estimated to be 15.5 million [5]. IPV and DV are currently recognized as forms of child abuse (CA) [6]. Despite not being direct victims of violence, children suffer lifelong adverse consequences from growing up in a harsh environment [7]. In particular, they tend to exhibit more psychosocial problems by internalizing and externalizing concerns [8]. Children of violent couples are also highly likely to be victims of other types of violence (“double whammy” phenomenon) [9] and are more prone to act violently in extra-domestic settings, leading to the so-called “cycle of violence” [10].

The identified cases of children exposed to DV are still minimal and only a small proportion receive assistance from child protection services [11], despite widespread awareness of the clinical consequences of exposure to violence. A gap seems to exist between the entity of the phenomenon, in terms of prevalence and morbidity, and the ability of the healthcare system to identify exposed children.

It is becoming increasingly clear that children who are direct victims of DV can be the protagonist of screening programs [12]. Indeed, the first opinions on the theme date back to early 1990, when some authors underlined the need for interviews regarding IPV in clinical settings [13]. In 2010, the American Academy of Pediatricians released a clinical report on children’s exposure to IPV and the role of pediatricians [14], which followed a previous position statement, highlighting the active role of health care providers in intercepting high-risk situations regarding IPV through appropriate information and training for intervention [15]. In the setting of primary care of children, most of the implemented IPV screening programs have been addressed to women rather than children, but there is still little evidence about performing universal versus risk-based screening [14]. Moreover, detailed guidelines for clinicians on how to perform the screening are still missing [16]. While pediatricians have been dealing with the idea of IPV screening for at least a decade, children’s psychiatrists do not seem to have addressed the issue, although the most immediate consequence on children’s health is related to psychopathological problems [2].

The present review addresses the need to revise the current literature in order to make clear the state of the art on screening for DV in pediatric clinics and in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). Indeed, clinicians still lack awareness and practical guidelines on the theme, and our study aims to point out any valuable clinical clues that can be helpful in children’s care settings. Moreover, our research aims to answer the following questions: in the pediatric population, does screening for DV increase the likelihood of detecting exposed children? Which is the best place, among pediatric health-care services, where screening should take place? Which patients should the screening involve? Which instruments are recommended, and which cautions are needed?

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Protocol

The methods of analysis and inclusion criteria were predefined and registered according to an internal study protocol.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included studies published in English between January 2000 and March 2021 on children under 18 years of age or on their caregivers in pediatric or mental health clinics that investigated screening strategies for DV exposure. Studies were excluded if they were any of the following: (i) systematic reviews; (ii) letters to editors; (iii) single case reports; or (iv) studies generally referring to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), child maltreatment, child trauma, or CA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria.

2.3. Sources of Information

The selected studies were identified through bibliographic research using electronic databases. Only articles in English were considered. Bibliographic research was conducted using the Sapienza Library System (Sistema Bibliotecario Sapienza, SBS), PubMed, and the following databases: MEDLINE (1966–present), American Psychological Association (APA) PsycArticles (1894–present), APA PsycInfo (1967–present), ScienceDirect, and Scopus. We considered a 20-year interval when selecting the articles. The last literature search was performed on 2 March 2021.

The following keywords were used for this search: domestic violence, family violence, and intimate partner violence, combined either with the word pediatric or the words children AND adolescent AND psychiatric clinic.

2.4. Study Selection

Eligibility assessment was performed through standardized open processes conducted by two independent reviewers. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by consensus. The first screening was performed by one reviewer, who reviewed the titles and abstracts. The selected articles then underwent full-text evaluation by the two reviewers independently in order to identify the most relevant studies according to our eligibility criteria.

2.5. Data Collection Process

Data were extracted according to the above-mentioned objective by two investigators independently; data were cross-verified for accuracy and completeness. Extracted data included the following: setting where the study was held, population characteristics, prevalence rates of DV, characteristics of the exposed sample, instruments used for the screening process, their methods of administration and their acceptability. Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

We described the results of the studies qualitatively and used tables of evidence. Studies were grouped according to the target population of the screening assessment (either caregivers or children).

3. Results

3.1. Available Literature

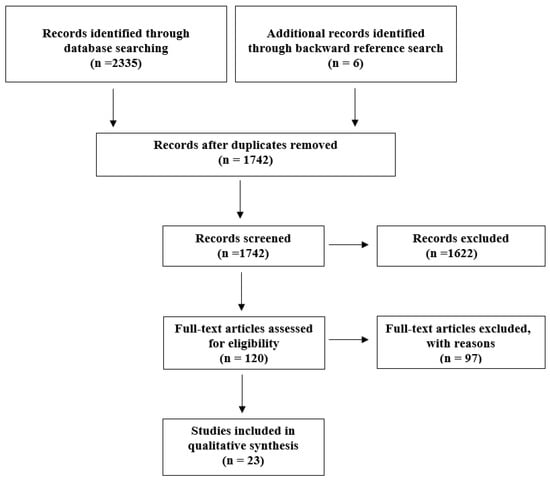

The first literature search yielded 2335 articles. After rejection of duplicates, 1742 titles and abstracts were read and 1622 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. We then examined the remaining 120 full-text articles. Six additional articles were added through a backward reference search and evaluated for eligibility. A total of 23 papers were selected according to eligibility criteria (Table 1). The flowchart summarizes the selection process used for the present review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for articles selection.

The settings of all studies are shown in Table 2. There were considerably more studies on the topic of DV screening in pediatric clinics vs. CAMHS (18 vs. 5; 78% vs. 22%). We found more studies in primary care clinics [12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] (11, 48%) than in pediatric emergency departments (EDs) (5, 22%) [27,28,29,30,31]. Only one study included data on inpatients [31]. Twenty articles (87%) focused on DV screening in mothers [12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], while three (13%) focused on DV screening in children and adolescents [2,36,37]. We will discuss these studies separately.

Table 2.

Selected studies, setting, study design.

3.2. Studies on DV Screening in Mothers

3.2.1. Settings and Samples

Studies were heterogeneous in terms of sample size and timeframe considered for exposure (Table 3). Most studies used a convenience sample recruited from clinical practices or EDs. The sample size varied widely, from only 90 families [34] to over 13,000 units [29]. In all studies except one [34], only mothers were selected for screening and the presence of a male partner was an exclusion criterion to guarantee the woman’s safety [23,25,26,27,30,32,38]. In many cases, if a child older than 3 years of age was present, the interview was not performed unless it was possible to send the child out of the room [21], an important limitation in pediatric clinics, where separating children from parents might not be feasible [39]. Demographic characteristics of the total sample were often not specified. Overall, studies were conducted in areas with an adequate variety of sociodemographic characteristics; the population ranged from married couples mostly covered by private insurance [12] to disadvantaged communities, with rates of adherence to aid programs (e.g., Medicaid) up to 93% and rates of single parenthood up to 85% [17]. Most studies reached women between 20 and 30 years of age who were mothers of young children, mostly preschoolers.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics of selected samples; DV and IPV. Prevalence rates and risk factors.

3.2.2. Disclosure Rates

The prevalence of disclosed DV ranged from 4.2% [31] to 48% [34], with most prevalence estimates between 10% and 20%. Data from CAMHS were fewer and more heterogeneous; a prevalence of 48% was found with a very small sample [34], while another showed a prevalence of 21% [35]. When DV that occurred in the past 12 months was investigated, the prevalence was found to be lower in some studies (between 0.5% [24] and 3.7% [21]), but not in others (10% [38]–11% [27]). When current abuse was investigated, the prevalence decreased drastically, ranging from 2% to 2.5% [12,22]. However, no consistent definitions of “current” or “past abuse” [21,28,29] are available.

3.2.3. Characteristics of Exposed Sample

Only eight studies (40%) provided specific data on women exposed to DV [12,18,20,26,27,32,34,35]. A higher risk of DV exists for young women [18], families more often involved in criminal investigations and/or parental custody battles [35], mothers who report a history of harm to the child [12], mothers who are in a relationship other than the first marriage [12], those with four or more children [12], those who are eligible for WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, infants and Children), and those who previously “no-showed” for a child’s wellbeing visit [12]. No relation was found between DV and race, ethnicity, poverty, or the child’s diagnosis (illness or injury) [27], and no significant differences were found in terms of marital status, income, number of children [18], sex, children’s and mothers’ age or nationality [35]. One study showed a higher risk for women who had not completed high school [27], but two studies did not confirm this data [18,35].

Only three of the examined studies (15%) specifically explored the psychopathology of parents or children [18,19,34]; they reported higher frequency of depressive symptoms [18] in exposed mothers and more common behavioral [19], internalizing and externalizing problems [18,34] that increased with age [19].

3.2.4. Screening Instruments and Acceptability

DV was directly assessed in all studies, since parental reporting is essential for disclosure [31]. The studies differed according to the instruments used and the method of administration (Table 4 and Table 5). Written tools were used in 55% of the studies, oral interviews in 40%, and computer instruments in 20%. Mixed forms were used in three studies (15%) [23,25,38]. The most used and effective tool appeared to be the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) [40] (30% of studies). The use of a shorter questionnaire as a first screening tool appeared advantageous [17,24], while the extended CTS provided a detailed characterization of the type of violence [24]. In contrast, the Partner Violence Screen (PVS) [41] was used for an initial assessment in 15% of the studies, especially those conducted in Eds. [21,27,29,38]. The PVS has the advantage of short and direct questions and the disadvantage of being limited to the previous 12 months [21]. Some new screening tools showed low sensitivity [17,23], although they might be sufficient to permit disclosure from women who are ready to disclose violence. Women showed good acceptance of DV screening within the clinical setting (70–80% acceptance rates [12,24,27]). No differences in DV disclosure rates between different formats, including verbal, written, computer [23], or audiotape questionnaires, were found in two studies, although a better outcome of oral surveys in comparison to written interviews was reported in one study. However, DV prevalence in the written interview group was noticeably low (0%) [25]. A caregiver-initiated computerized system had the advantage of recruiting large samples and was appreciated in terms of privacy, although it was not compared to any other method in the study [29]. Women preferred direct verbal questioning in the study of Newman et al. [27], and audiotapes in the study by Bair-Merritt et al. [38]. Findings regarding the use of informative materials to facilitate disclosure within the pediatric setting were controversial and inconclusive [28,33].

Table 4.

Questionnaires, type of questions, administration, acceptability rate of the screening tests.

Table 5.

Percentage of usage of different screening tools.

3.3. Studies on DV Screening in Children

3.3.1. Setting and Samples

Three of the selected studies investigated the feasibility of screening for DV in minors recruited from CAMHS in three countries, Sweden [2], Austria [37], and Spain [36] (Table 6). The three studies together enrolled a total of 1891 children aged 6 to 20 years, with an equal gender distribution. Study designs were similar; they explored personal experiences of interpersonal violence using an interview addressed to children. The study by Olaya et al. investigated DV exclusively [36], while Hultmann and Broberg and Völkl-Kernstock et al. explored DV among other forms of interpersonal violence [2,37].

Table 6.

Studies on children.

3.3.2. Disclosure Rates

The study by Olaya et al. found a DV prevalence of 19.2% [36]. Hultmann et al. reported a prevalence of family violence (FV) of 48%. This figure included 21% who were victims of FV only (21%) and 27% who were exposed to poly-victimization (FV and interpersonal violence) [2]. A total of 67% of responders experienced some type of violence. Völkl-Kernstock et al. found 75% of the sample had experienced violence, with DV being the most frequently reported (27% of the total sample) [37].

3.3.3. Characteristics of Exposed Sample

The most represented age group in the violence-exposed samples ranged between 11 and 17 years of age [2,36,37]. Regarding gender distribution, a lower percentage of males was found in the exposed group [36], especially in older ages [37], although males were prevalent in the group exposed to interpersonal violence [2]. Therefore, DV prevalence ranged from 19.2% to 48% and was the most frequent form of violence, being more common in females than males.

The exposed group presented a higher frequency of one-parent families [36], more frequent economic problems [36], and an increased probability of living with neither parent or under one-parent custody or being born abroad [2]. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of maternal and paternal age, education level, occupation, socioeconomic status, or perception of their neighborhood from a social point of view [36].

The study by Olaya et al. provided the most detailed information about parenting style as characterized by rejection, low emotional warmth, and less control [36]. Physical punishment was more frequent among fathers, whereas mothers were more overprotective towards males and more prone to physical punishment towards females [36]. Psychopathology was common within abusive families [36].

Psychiatric assessment of patients was a key point of all the selected studies. Self-administered questionnaires and clinical interviews were used. A higher number of diagnoses and symptoms in DV exposed children [36] and a significant correlation between DV and clinical diagnosis [37] were found. Exposed children showed a higher frequency of dysthymic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder [36], adjustment disorder, and attention-deficit or disruptive behavior diagnoses [2]. Males were more likely to be diagnosed with an externalizing diagnosis, while females most often received an internalizing diagnosis [37]. We found higher scores on externalizing and rule-breaking behavior subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), higher daily global impairment and an increased risk of self-harming behaviors [36], and higher scores on the total problem scale and peer problems on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [2]. Global functioning was overall lower in children in the exposed group [2].

3.3.4. Screening Instruments and Acceptability

The three selected studies approached DV detection from the child’s point of view.

Olaya et al. [36] used two items from the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIS) [42] and Hultmann and Broberg [2] used a modified version of the Life Incidence of Traumatic Events (LITE) [43]. Children who responded positively to one of the LITE questions were considered in the FV group, so that in this study, the sample was actually a group of poly-victimized children [2]. The scale, in the form of a questionnaire, was administered to children (without parents in the room) by clinicians during the first visit [2]. Völkl-Kernstock et al. [37] used the Childhood Trauma Interview (CTI) [44]. The investigation was performed by three child psychiatry residents in the form of a semi-structured interview. The authors did not specify which items were used to rate a child as positive for DV, and when describing the exposed children, they included witnessed violence as well as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and neglect within the DV category. In summary, in two of the three selected studies, children who were rated as positive for DV were not only exposed to interparental violence, but were also victims of FV.

4. Discussion

4.1. Does Screening for DV Increase the Opportunity of Detecting Exposed Children?

The current literature review shows prevalence rates of DV among mothers referring to pediatric clinics that fall between 10% and 20%, while previous observations estimate global lifetime prevalence of DV among women to be 30% (slightly lower in high income countries) [3]. In this case, DV screening within pediatric clinical setting seems to not be able to catch all the exposed families.

However, it shows good potential to detect those women who are seeking help [23]. An active plan for DV detection through the use of questionnaires, indeed, significantly increases disclosure rates [21,22], especially regarding past experiences, and women show good acceptance of it (70–80% acceptance rates [12,24,27]). The American Academy of Pediatrics, indeed, strongly recommends pediatric involvement by screening mothers for DV in order to prevent child maltreatment [14].

4.2. Where to Screen?

A total of 18 out of 23 studies were set in a pediatric setting, while only 5 were conducted in a CAMHS setting. This evidence is alarming, since children exposed to violence are at high risk of developing emotional and behavioral problems [8], and thus necessitate early referral to CAMHS practitioners. Psychiatrists’ awareness of the topic is even more urgent, since meta-analytic longitudinal studies have shown that the outcome of exposed children is not pre-determined by the event of exposure itself [45] and interventions can lead to healthy adjustment [8]. We found that 48% of studies on DV in the pediatric setting were conducted in primary care centers, while 22% were conducted in EDs. Disclosure rates were not markedly different. Pediatric primary care clinics offer the advantages of time availability and a trustworthy, longitudinal relationship between the healthcare provider and family [26]. Moreover, the lack of punctual child health monitoring itself has been described as a particular aspect of families with potential DV [17]. EDs are the most easily accessible clinical services. They might help to screen women without the violent partner present, which would facilitate DV disclosure [29]. In contrast, the frenetic timing and impossibility of performing screening during night hours or when the conditions of the child are too severe reduce screening opportunities [27]. The study by Cruz et al. highlighted the possibility of disclosure among inpatients [32], which appears to be an interesting and underexplored topic, while no clear advantages have emerged in terms of choosing primary care vs. EDs.

4.3. When to Screen: Risk-Based Versus Universal

All the examined studies conducted universal screening, although universal screening for DV within the clinical setting has been criticized [46]. Current WHO guidelines suggest risk-based interviews only and a list of risk factors suggestive of DV is available [47], although they do not allow practical interpretation. A review of the current literature highlighted young maternal age [18], not having completed high school [27], being in a relationship other than a first marriage, having four or more children, being WIC eligible, having previously “no-showed” for a well-child visit [12] and having sole custody or pending legal concerns [35] as risk factors. The strength of this evidence is still very limited, since each factor is reported in only one or a few studies with limited samples. Of the potential risk factors, punctuality in providing healthcare for children [12] and custody status [35] appear to be potentially effective elements for the detection of DV by clinical practitioners and should be better investigated. Lower disclosure rates were found in studies with a high number of patients covered by Medicaid (3.7% to 15%) [21,22], although Siegel et al. suggested that indigent patients more readily disclose recent abuse [20]. No differences in disclosure rates emerged between different environmental and sociodemographic settings (i.e., suburbs, large cities).

Meta-analytic studies are needed to extract quantitative data on risk factors related to DV in the pediatric healthcare setting.

4.4. Who to Screen?

Most screening programs for DV are addressed to women [46]. Indeed, most selected studies used screening tools only on mothers, and the presence of a male partner was an exclusion criterion [20,26]. This approach guarantees safety, although future screening programs should include both male and female caregivers [6]. Paternal reports of DV are important to identify bilateral violence and to have more consistent data on children’s problems [34]. Data are scarce regarding caregivers who lost child custody or who were already in contact with social services, and in many studies, they were either excluded or not mentioned. The role of children and adolescents in DV disclosure and its practical implications have been explored in just three of the selected studies [2,36,37]. Ethical questions arise when interviewing young children on this topic [48]; children might provide incoherent narratives or remove events as a means of defense [49] and currently used screening tools were found to have poor psychometric properties [50]. Only one selected study used an oral interview for children [37], consistent with the suggestion that once children can speak, healthcare providers should try direct assessment [6]. The prevalent age group was 12–17 years [2,36,37] among the studies in children, while for children aged 0–7 years, the caregivers were interviewed. Therefore, it appears that maternal screening tools are the most feasible and widely used tools to assess child exposure to DV in the pediatric setting, especially for young children, who are disproportionately represented among families characterized by current DV [4,51,52]. More direct involvement of minors with the appropriate instruments and an empathic approach should not be excluded, especially after a certain age.

4.5. How to Screen? Instruments and Cautions

It is necessary to directly ask and involve families in DV screening to obtain a higher disclosure rate [31]. An active plan for DV detection using questionnaires increases disclosure rates significantly [21,22], and even a brief question on DV can be effective as compared to longer screening methods [17]. The most used instruments were the PVS [41] in EDs and the CTS [40] for more detailed knowledge of exposure. Some instruments with low sensitivity could be useful because they might detect only those subjects who are more inclined to benefit from an intervention due to their willingness to disclose and improve their current situation [23]. Most of the analyzed studies (69.5%) used written or computerized tools, which have been proven to be more effective in adult-care settings [30] and more acceptable to women because they are easier and more confidential [53]. These data have only partially been confirmed within the pediatric setting, where direct verbal questioning was preferred [27] or showed higher disclosure rates [29] in some studies, although not in others [54]. More data need to be collected on the topic. Computer inquiries and audiotape interviews [38] about sensitive issues have been shown to yield the highest detection rates [55]. The topic of displaying posters for children is controversial due to contrasting results [28,33]. Use of nongraphic tools (i.e., not directly mentioning words such as hitting, abuse) could make it possible to screen women, even when children are present [23].

5. Limitations

We limited our review to the first point of the screening process, without evaluating experiences about the actual change after detection. The lack of long-term benefits has been shown in adult clinical care as one of the main critical points for promoting DV screening [46]. Moreover, further attention should be given to studies that focus on healthcare providers’ point of view in this process.

6. Conclusions

The topic of DV and its impact on child development has captured the attention of clinicians within the last few decades, although research is still scarce, especially within the child psychiatric setting [2,34,35,36,37]. Practitioners who encounter minors in their routine practice need increased awareness of this issue. More detailed guidelines can be useful to facilitate and manage disclosure. An active plan for DV identification significantly increases disclosure rates [21,22] and make it possible to detect those women who are prone to change their condition [23]. Conducting risk-based screening is challenging because the currently identified risk factors are too vague [47]. Greater attention to patient sociodemographic data, custody situations and punctuality in child health monitoring might be helpful to detect DV [12,18,35]. No differences were identified in screening effectiveness between primary care centers and Eds, while inpatient screening should be further evaluated. For young children, parental reports [1] are advisable, while for older children, direct involvement with adequate training and instruments should not be excluded. Data on paternal screening are lacking, but they might help to increase disclosure rates [34]. The use of questionnaires is suggested [21,22] and even a brief question on DV can be effective [17].

7. Future Perspectives

In conclusion, the findings from our literature review confirm that actively screening for DV within pediatric clinical services cannot be recommended yet, although it appears crucially important for health professionals to be prepared to actively screen for DV if any doubt arises from the clinical history of the child. We propose that clinicians should be ready to further interview families if any risk factors for DV are detected. We call for an expansion of Thackeray’s indications [14] in order to move towards the development of more detailed clinical guidelines regarding the procedures and interventions.

Further investigations should focus on long-term outcomes after disclosure, as well as on the point of view of healthcare providers. Moreover, a further meta-analytic study of the results obtained in the present review would be useful to examine the quantitative relevance of the topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and C.S.; methodology, M.R. and F.A.; software, M.A.; validation, C.S. and M.R.; formal analysis, M.A. and E.A.; investigation, M.A. and E.A.; resources, M.A., E.A., G.C.; data curation, F.A. and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.R., F.A., E.A.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, C.S. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Breiding, M.J.; Basile, K.C.; Smith, S.G.; Black, M.C.; Mahendra, R. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Defintions and Recommended Data Elements; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hultmann, O.; Broberg, A.G. Family Violence and Other Potentially Traumatic Interpersonal Events Among 9- to 17-Year-Old Children Attending an Outpatient Psychiatric Clinic. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 2958–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo, J.W.; Mohr, W.K. Prevalence and effects of child exposure to domestic violence. Future Child. 1999, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.; Jouriles, E.N.; Ramisetty-Mikler, S.; Caetano, R.; Green, C.E. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macmillan, H.L.; Wathen, C.N. Children ’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Williamson, D.F. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: Implications for health and social services. Violence Vict. 2002, 17, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Buckley, H.; Whelan, S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abus. Negl. 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, H.M.; Parkinson, D.; Vargo, M. Witnessing spouse abuse and experiencing physical abuse: A “double whammy”? J. Fam. Violence 1989, 4, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.N.; Tomsich, E.; Gover, A.R.; Jennings, W.G. The Cycle of Violence Revisited: Distinguishing Intimate Partner Violence Offenders Only, Victims Only, and Victim-Offenders. Violence Vict. 2016, 31, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.; Widom, C.S.; Browne, K.; Fergusson, D.; Webb, E.; Janson, S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009, 373, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, G.W.; Adams, R.C.; Emerling, F.G. Maternal domestic violence screening in an office-based pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2001, 108, E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children of Battered Women—PsycNET. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-97763-000 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Thackeray, J.D.; Hibbard, R.; Dowd, M.D.; Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect; Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Intimate partner violence: The role of the pediatrician. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, J.A.; Alexander, R.C.; Block, R.W.; Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The role of the pediatrician in recognizing and intervening on behalf of abused women. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Campo, P.; Kirst, M.; Tsamis, C.; Chambers, C.; Ahmad, F. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: Evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz, H.; Prescott, L.; Feigelman, S.; Lane, W.; Kim, J. Screening for intimate partner violence in a pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e85–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, B.J.; Porcerelli, J.H.; Sklar, E.R.; Markova, T. Pediatric symptom checklist ratings by mothers with a recent history of intimate partner violence: A primary care study. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2013, 20, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, J.M.; Groff, J.Y.; O’Brien, J.A.; Watson, K. Behaviors of children who are exposed and not exposed to intimate partner violence: An analysis of 330 black, white, and Hispanic children. Pediatrics 2003, 112, e202–e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.M.; Joseph, E.C.; Routh, S.A.; Mendel, S.G.; Jones, E.; Ramesh, R.B.; Hill, T.D. Screening for domestic violence in the pediatric office: A multipractice experience. Clin. Pediatr. 2003, 42, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtrop, T.G.; Fischer, H.; Gray, S.M.; Barry, K.; Bryant, T.; Du, W. Screening for domestic violence in a general pediatric clinic: Be prepared! Pediatrics 2004, 114, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, R.A.; Sisk, D.J.; Ball, T.M. Clinic-based screening for domestic violence: Use of a child safety questionnaire. BMC Med. 2004, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zink, T.; Levin, L.; Putnam, F.; Beckstrom, A. Accuracy of five domestic violence screening questions with nongraphic language. Clin. Pediatr. 2007, 46, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almqvist, K.; Källström, Å.; Appell, P.; Anderzen-Carlsson, A. Mothers’ opinions on being asked about exposure to intimate partner violence in child healthcare centres in Sweden. J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderst, J.; Hill, T.D.; Siegel, R.M. A Comparison of Domestic Violence Screening Methods in a Pediatric Office. Clin. Pediatr. 2004, 43, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Jennings, J.M.; Eaker, K.; Tuman, J.L.; Park, S.M.; Cheng, T.L. Screening for domestic violence and childhood exposure in families seeking care at an urban pediatric clinic. J. Pediatr. 2008, 152, 734–736.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, J.D.; Sheehan, K.M.; Powell, E.C. Screening for Intimate-Partner Violence in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2005, 21, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, K.A.; Sherman, A.; Walsh, I.; O’Malley, D.; Dowd, M.D. Intimate Partner Violence Educational Materials in the Acute Care Setting: Acceptability and Impact on Female Caregiver Attitudes Toward Screening. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2021, 37, e37–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribano, P.V.; Stevens, J.; Marshall, J.; Gleason, E.; Kelleher, K.J. Feasibility of computerized screening for intimate partner violence in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2011, 27, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Mollen, C.J.; Yau, P.L.; Fein, J.A. Impact of domestic violence posters on female caregivers’ opinions about domestic violence screening and disclosure in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2006, 22, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerker, B.D.; Horwitz, S.M.C.; Leventhal, J.M.; Plichta, S.; Leaf, P.J. Identification of violence in the home: Pediatric and parental reports. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Cruz, P.B.; Weirich, C.; McGorty, R.; McColgan, M.D. Referral patterns and service utilization in a pediatric hospital-wide intimate partner violence program. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Blackstone, M.; Feudtner, C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e278–e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Jouriles, E.N.; Norwood, W.; Ware, H.S.; Ezell, E. Husbands’ marital violence and the adjustment problems of clinic-referred children. Behav. Ther. 2000, 31, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultmann, O.; Broberg, A.G.; Hedtjarn, G. One out of five mothers of children in psychiatric care has experienced violence. Lakartidningen 2009, 106, 3242–3247. [Google Scholar]

- Olaya, B.; Ezpeleta, L.; de la Osa, N.; Granero, R.; Doménech, J.M. Mental health needs of children exposed to intimate partner violence seeking help from mental health services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Huemer, J.; Jandl-Jager, E.; Abensberg-Traun, M.; Marecek, S.; Pellegrini, E.; Plattner, B.; Skala, K. Experiences of Domestic and School Violence Among Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Outpatients. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Feudtner, C.; Mollen, C.J.; Winters, S.; Blackstone, M.; Fein, J.A. Screening for intimate partner violence using an audiotape questionnaire: A randomized clinical trial in a pediatric emergency department. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, T.M.; Jacobson, J. Screening for Intimate Partner Violence when Children are Present: The Victim’s Perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, R.M. Conflict Tactics Scale. In Encyclopedia of Family Studies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldhaus, K.M.; Koziol-McLain, J.; Amsbury, H.L.; Norton, I.M.; Lowenstein, S.R.; Abbott, J.T. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA 1997, 277, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Seid, M.; Fincham, F.D. Assessing Marital Conflict from the Child’s Perspective: The Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, R.; Rubin, A. Brief assessment of children’s post-traumatic symptoms: Development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 1999, 9, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L.A.; Bernstein, D.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J.; Lovejoy, M. Initial reliability and validity of the childhood trauma interview: A new multidimensional measure of childhood interpersonal trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.A.; Crooks, C.V.; Lee, V.; McIntyre-Smith, A.; Jaffe, P.G. The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 6, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Doherty, L.; Hegarty, K.; Ramsay, J.; Davidson, L.L.; Feder, G.; Taft, A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO); London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Øverlien, C. “He didn’t mean to hit mom, I think”: Positioning, agency and point in adolescents’ narratives about domestic violence. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2014, 19, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgsson, A.; Almqvist, K.; Broberg, A.G. Naming the Unmentionable: How Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence Articulate Their Experiences. J. Fam. Violence 2011, 26, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edleson, J.L.; Ellerton, A.L.; Seagren, E.A.; Kirchberg, S.L.; Schmidt, S.O.; Ambrose, A.T. Assessing child exposure to adult domestic violence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2007, 29, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuti, V.; Marini, I.; Grillo, A.; Lauriola, M.; Leone, C.; Giacchetti, N.; Aceti, F. MMPI-2: Cluster analysis of personality profiles in perinatal depression—Preliminary evidence. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 964210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martucci, M.; Fava, G.; Giacchetti, N.; Aceti, F.; Galeoto, G.; Panfili, M.; Sogos, C. Perinatal depression as a risk factor for child developmental disorders: A cross-sectional study. Riv. Psichiatr. 2021, 56, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.H.; Rovi, S.; Washington, J.; Jacobs, A.; Vega, M.; Pan, K.-Y.; Johnson, M.S. Randomized comparison of 3 methods to screen for domestic violence in family practice. Ann. Fam. Med. 2007, 5, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, T.; Klesges, L.M.; Levin, L.; Putnam, F. Abuse behavior inventory: Cutpoint, validity, and characterization of discrepancies. J. Interpers. Violence 2007, 22, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.V.; Lauderdale, D.S.; He, T.; Howes, D.S.; Levinson, W. “Between me and the computer”: Increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2002, 40, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).