Has the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Been Considered in Studies Investigating Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identify the Research Question

2.2. Identify Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

- (1)

- A group of women (age >18 years) diagnosed with TTH or migraine according to the IHS criteria. Studies including both women and men were also included but the main analysis, obviously, considered just the female group.

- (2)

- A control group of healthy women without history of headache.

- (3)

- Full text report published in Spanish or English as a journal article.

- (4)

- Pressure pain sensitivity evaluated with PPTs assessed with a pressure algometer or dynamometer as the primary outcome.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Studies assessing pain sensitivity with manual palpation or with other outcomes rather than an algometer (e.g., Von-Frey monofilament).

- (2)

- Experimental-induced pain models (healthy subjects receiving a hypertonic saline injection or similar) of TTH or migraine.

- (3)

- In those studies, evaluating different quantitative sensory tests, such as thermal or electrical pain thresholds, only PPTs measured with an algometer or dynamometer were included.

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Methodological Quality

3. Results

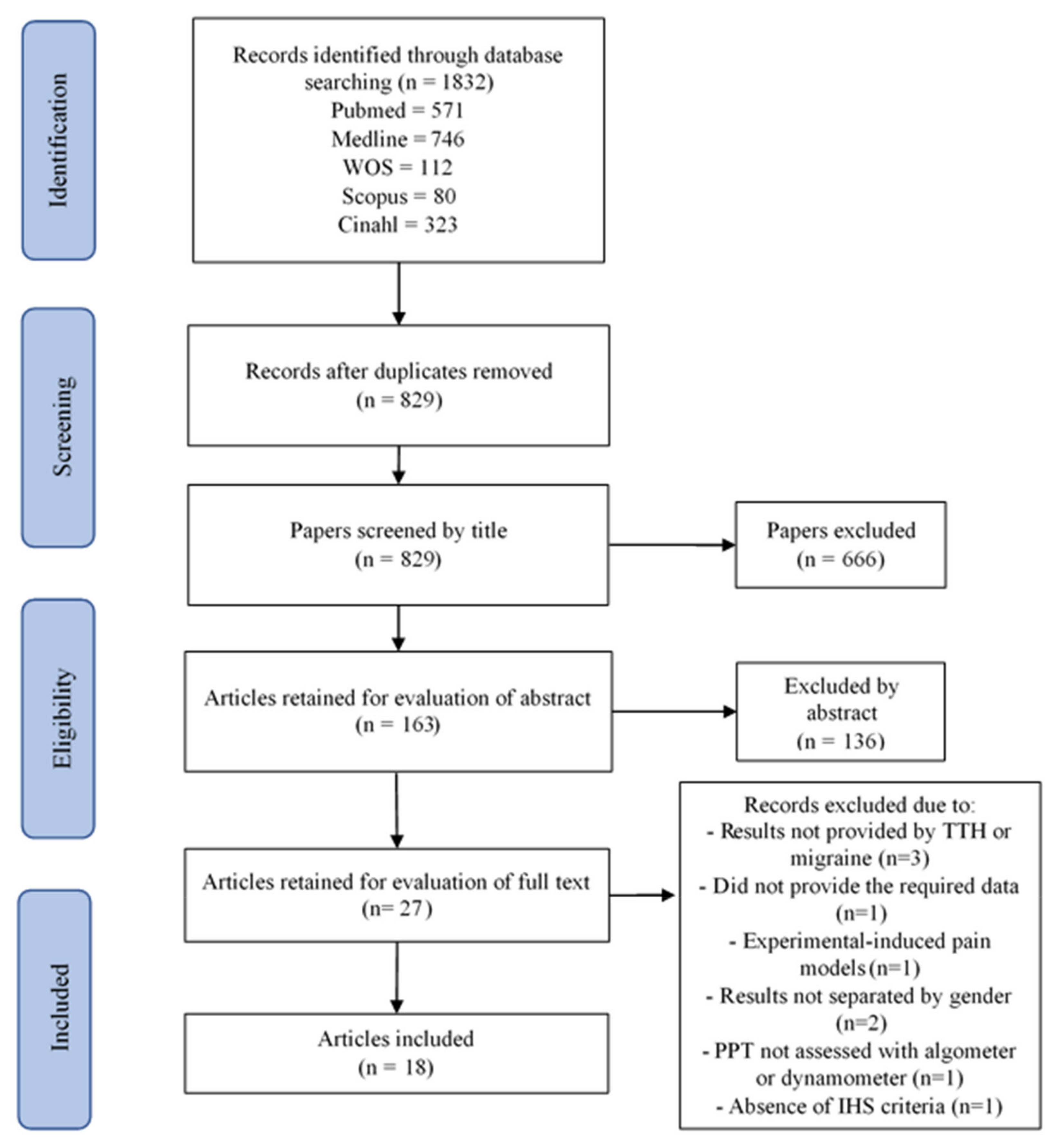

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

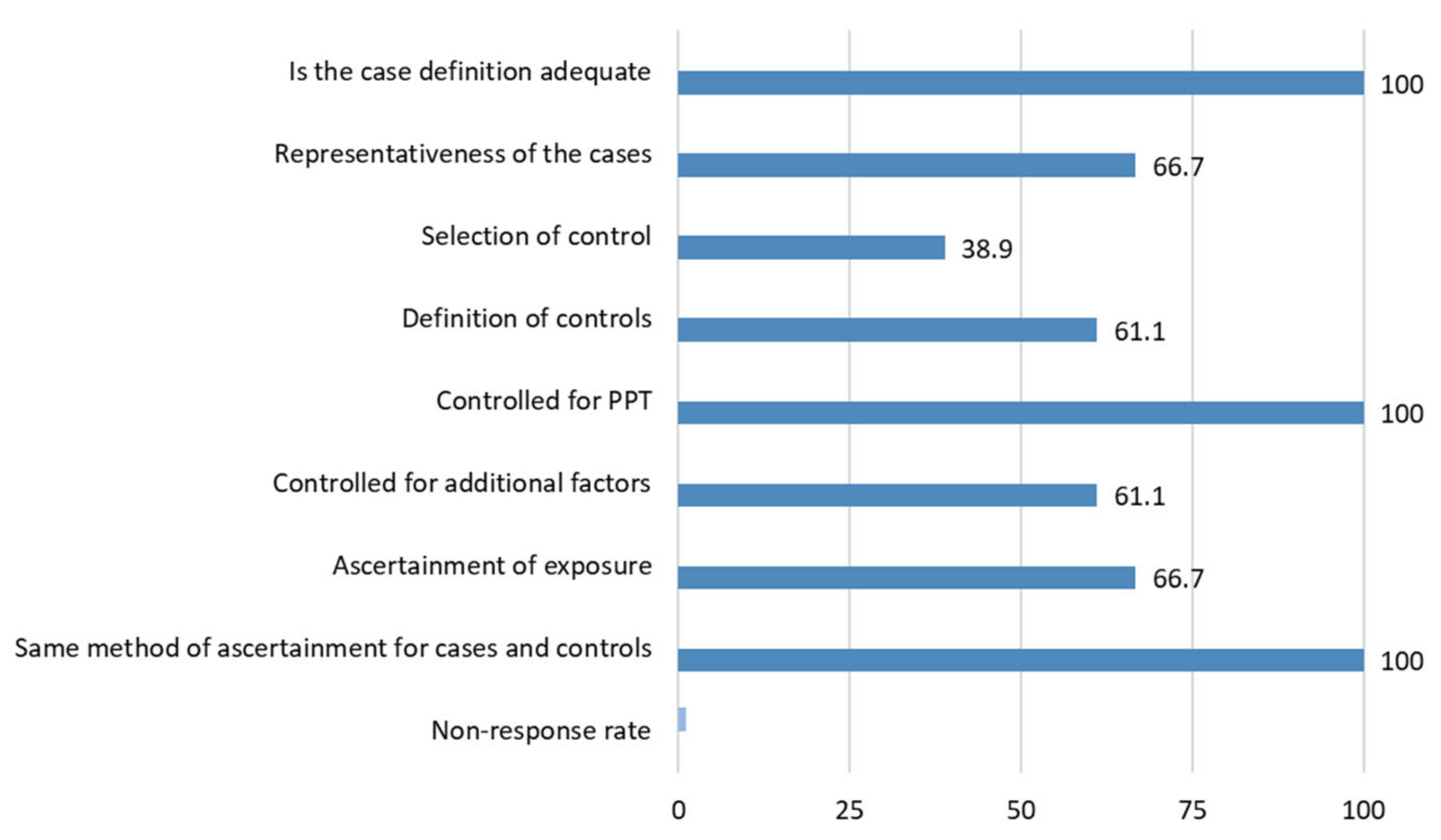

3.3. Methodological Quality

3.4. Consideration of Menstrual Cycle

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Reliability and Validity of Pressure Pain Thresholds

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2013, 386, 743–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Vos, T. GBD 2015: Migraine is the third cause of disability in under 50s. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nahman-Averbuch, H.; Shefi, T.; Schneider, V.J.; Li, D.; Ding, L.; King, C.D.; Coghill, R.C. Quantitative sensory testing in patients with migraine: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2018, 159, 1202–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M.J.; Olesen, J.; Jensen, R.H.; Bendtsen, L. Evidence of localized and widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity in patients with tension-type headache: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 2020, 41, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo-Urriés, M.; Estébanez-de-Miguel, E.; Bueno-Gracia, E.; Tricás-Moreno, J.M.; Santos-Lasaosa, S.; Hidalgo-García, C. Sensory function in headache: A comparative study among patients with cluster headache, migraine, tension-type headache, and asymptomatic subjects. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 2801–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovim, G. Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain 1992, 51, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Ceña, M.; Castaldo, M.; Kelun, W.; Torelli, P.; Pillastrini, P.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity is similar in women with frequent episodic and chronic tension-type headache: A blinded case–control study. Headache 2016, 57, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cássia Correia Kälberer Pires, R.; Salles da Rocha, N.; Esteves, J.E.; Rodrigues, M.E. Use of pressure dynamometer in the assessment of the pressure pain threshold in trigger points in the craniocervical muscles in women with unilateral migraine and tension-type headache: An observational study. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 26, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Ge, H.Y.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Madeleine, P.; Pareja, J.A.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Bilateral pressure pain sensitivity mapping of the temporalis muscle in chronic tension-type headache. Headache 2008, 48, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Madeleine, P.; Caminero, A.B.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Pareja, J.A. Generalized neck-shoulder hyperalgesia in chronic tension-type headache and unilateral migraine assessed by pressure pain sensitivity topographical maps of the trapezius muscle. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Madeleine, P.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Ge, H.Y.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Pareja, J.A. Pressure pain sensitivity mapping of the temporalis muscle revealed bilateral pressure hyperalgesia in patients with strictly unilateral migraine. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales Pinto, L.M.; Freitas de Carvalho, J.J.; Cunha, C.; dos Santos Silva, R.; Fiamengui-Filho, J.F.; Rodrigues Conti, P.C. Influence of myofascial pain on the pressure pain threshold of masticatory muscles in women with migraine. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio, L.L.; Giantomassi, M.C.M.; Carvalho, G.F.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Dach, F.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Bevilaqua-Grossi, D. Generalized pressure pain hypersensitivity in the cervical muscles in women with migraine. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palacios-Ceña, M.; Florencio, L.L.; Ferracini, G.N.; Barón, J.; Guerrero, Á.L.; Ordás-Bandera, C.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Women with chronic and episodic migraine exhibit similar widespread pressure pain sensitivity. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coppola, G.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Schoenen, J.; Pierelli, F. Habituation and sensitization in primary headaches. J. Headache Pain 2013, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommaso, M. Pain perception during menstrual cycle. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2011, 15, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, B.; Ibuki, F.; Gonçalves, A.S.; Teixeira, M.J.; Siqueira, S.R.D.T. Influence of sexual hormones on neural orofacial perception. Pain Med. 2017, 18, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousignant-Laflamme, Y.; Marchand, S. Excitatory and inhibitory pain mechanisms during the menstrual cycle in healthy women. Pain 2009, 146, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.T. Ovarian hormones and pain response: A review of clinical and basic science studies. Gend. Med. 2009, 6, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limmroth, V.; Lee, W.S.; Moskowitz, M.A. GABAA-receptor-mediated effects of progesterone, its ring-A-reduced metabolites and synthetic neuroactive steroids on neurogenic oedema in the rat meninges. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 117, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palacios-Ceña, D.; Albaladejo-Vicente, R.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Lima-Florencio, L.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Jimenez-Garcia, R.; López-de-Andrés, A.; de Miguel-Diez, J.; Perez-Farinos, N. Female gender is associated with a higher prevalence of chronic neck pain, chronic low back pain, and migraine: Results of the Spanish National Health Survey, 2017. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuensalida-Novo, S.; Jiménez-Antona, C.; Benito-González, E.; Cigarán-Méndez, M.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C. Current perspectives on sex differences in tension-type headache. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2020, 20, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.J. In no uncertain terms: The importance of a defined objective in scoping reviews. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Reports 2016, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004, 24, 9–160.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia 1988, 1–96.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Ashina, S.; Bendtsen, L.; Buse, D.C.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Lipton, R.B.; Jensen, R. Neuroticism, depression and pain perception in migraine and tension-type headache. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017, 136, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, S.; Lipton, R.B.; Bendtsen, L.; Hajiyeva, N.; Buse, D.C.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Jensen, R. Increased pain sensitivity in migraine and tension-type headache coexistent with low back pain: A cross-sectional population study. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylleraas, S.; Male Davidsen, E.; Saltyte Benth, J.; Gulbrandsen, P.; Dietrichs, E. The usefulness of testing head and neck muscle tenderness and neck mobility in acute headache patients. Funct. Neurol. 2010, 25, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sand, T.; Zwart, J.A.; Heide, G.; Bovim, G. The reproducibility of cephalic pain pressure thresholds in control subjects and headache patients. Cephalalgia 1997, 17, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, H.; Weigle, L.; Christiani, K. Headache characteristics in patients with tension-type headache in relationship to pericranial muscle pain sensitivity. Cephalalgia 1991, 11, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, H.; Weigle, L.; Kropp, P.; Soyka, D. Pain sensitivity and pain reactivity of pericranial muscles in migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 1992, 12, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipchik, G.; Holroyd, K.; O’Donnell, F.; Cordingley, G.; Waller, S.; Labus, J.; Davis, M.; French, D. Exteroceptive suppression periods and pericranial muscle tenderness in chronic tension-type headache: Effects of psychopathology, chronicity and disability. Cephalalgia 2000, 20, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, J.D.; Holroyd, K.A.; Lipchik, G.L. Dynamic assessment of abnormalities in central pain transmission and modulation in tension-type headache sufferers. Headache 2000, 40, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Kang, W.-C.; Hong, K.-E. Analysis of the change of the pressure pain threshold in chronic tension-type headache and control. J. Korean Inst. Herb. Acupunct. 2009, 12, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Chung, S.C.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.W. Pain-pressure threshold in the head and neck region of episodic tension-type headache patients. J. Orofac. Pain 1995, 9, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, P.D. Scalp tenderness and sensitivity to pain in migraine and tension headache. Headache J. Head Face Pain 1987, 27, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.; Rasmussen, B.K. Muscular disorders in tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 1996, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini, G.; Proietti Cecchini, A.; Milanov, I.; Tassorelli, C.; Buzzi, M.G.; Nappi, G. Electrophysiological evidence for trigeminal neuron sensitization in patients with migraine. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 317, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamaño-Barrios, L.H.; Galan-Del-Rıo, F.; Fernandez-De-las-Peñas, C.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Ortega-Santiago, R. Widespread pressure pain sensitivity over nerve trunk areas in women with frequent episodic tension-type headache as a sign of central sensitization. Pain Med. 2019, 21, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathcart, S.; Pritchard, D. Daily stress and pain sensitivity in chronic tension-type headache sufferers. Stress Health 2008, 24, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, P.D.; Knudsen, L. Central pain modulation and scalp tenderness in frequent episodic tension-type headache. Headache 2011, 51, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engstrøm, M.; Hagen, K.; Bjørk, M.; Stovner, L.J.; Stjern, M.; Sand, T. Sleep quality, arousal and pain thresholds in tension-type headache: A blinded controlled polysomnographic study. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Coppieters, M.W.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Pareja, J.A. Patients with chronic tension-type headache demonstrate increased mechano-sensitivity of the supra-orbital nerve. Headache 2008, 48, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Ge, H.Y.; Pareja, J.A. Increased pericranial tenderness, decreased pressure pain threshold, and headache clinical parameters in chronic tension-type headache patients. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Ge, H.Y.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Pareja, J.A. The local and referred pain from myofascial trigger points in the temporalis muscle contributes to pain profile in chronic tension-type headache. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Ge, H.Y.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Pareja, J.A. Referred pain from trapezius muscle trigger points shares similar characteristics with chronic tension type headache. Eur. J. Pain 2007, 11, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, E.; Latysheva, N.; Kurenkov, A. Evidence of persistent central sensitization in chronic headaches: A multi-method study. J. Headache Pain 2008, 9, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, R. Mechanisms of spontaneous tension-type headaches: An analysis of tenderness, pain thresholds and EMG. Pain 1995, 64, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.; Bendtsen, L.; Olesen, J. Muscular factors are of importance in tension-type headache. Headache 1998, 38, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, R.; Rasmussen, B.K.; Pedersen, B.; Olesen, J. Muscle tenderness and pressure pain thresholds in headache. A population study. Pain 1993, 52, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemark, M.; Jensen, K.; Jensen, T.S.; Olesen, J. Pressure pain thresholds and thermal nociceptive thresholds in chronic tension-type headache. Pain 1989, 38, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, G.; Sarchielli, P.; Gaggioli, A.; Gallai, V. Study of pressure pain and cellular concentration of neurotransmitters related to nociception in episodic tension-type headache patients. Headache 1997, 37, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddireddy, A.; Wang, K.; Svensson, P.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Stretch reflex and pressure pain thresholds in chronic tension-type headache patients and healthy controls. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Morales, C.; Jaén-Crespo, G.; Rodríguez-Sanz, D.; Sanz-Corbalán, I.; López-López, D.; Calvo-Lobo, C. Comparison of pressure pain thresholds in upper trapezius and temporalis muscles trigger points between tension type headache and healthy participants: A case–control study. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2017, 40, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini, G.; Antonaci, F.; Pucci, E.; Bono, G.; Nappi, G. Comparative study with EMG, pressure algometry and manual palpation in tension-type headache and migraine. Cephalalgia 1994, 14, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenen, J.; Bottin, D.; Hardy, F.; Gerard, P. Cephalic and extracephalic pressure pain thresholds in chronic tension-type headache. Pain 1991, 47, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroppa-Marques, A.E.Z.; De Melo-Neto, J.S.; Do Valle, S.P.; Pedroni, C.R. Muscular pressure pain threshold and influence of craniocervical posture in individuals with episodic tension-type headache. Coluna Columna 2017, 16, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthaikhup, S.; Sterling, M.; Jull, G. Widespread sensory hypersensitivity is not a feature of chronic headache in elders. Headache 2009, 50, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashina, S.; Babenko, L.; Jensen, R.; Ashina, M.; Magerl, W.; Bendtsen, L. Increased muscular and cutaneous pain sensitivity in cephalic region in patients with chronic tension-type headache. Eur. J. Neurol. 2005, 12, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendtsen, L.; Jensen, R.; Olesen, J. Decreased pain detection and tolerance thresholds in chronic tension-type headache. Arch. Neurol. 1996, 53, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchgreitz, L.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Bendtsen, L.; Jensen, R. Frequency of headache is related to sensitization: A population study. Pain 2006, 123, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchgreitz, L.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Bendtsen, L.; Jensen, R. Increased pain sensitivity is not a risk factor but a consequence of frequent headache: A population-based follow-up study. Pain 2008, 137, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, H.; Çilliler, A.E.; Çomoǧlu, S.S. Cutaneous allodynia in patients with episodic migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.C.; Chaves, T.C.; Florencio, L.L.; Carvalho, G.F.; Dach, F.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Bevilaqua-Grossi, D. Is pressure pain sensitivity over the cervical musculature associated with neck disability in individuals with migraine? J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2015, 19, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, R.; Yarnitsky, D.; Goor-Aryeh, I.; Ransil, B.; Bajwa, Z. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, H.G.; Tunis, M.M.; Goodell, H. Studies on headache: Evidence of tissue damage and changes in pain sensitivity in subjects with vascular headaches of the migraine type. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 1953, 92, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barón, J.; Ruiz, M.; Palacios-Ceña, M.; Madeleine, P.; Guerrero, Á.L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Differences in topographical pressure pain sensitivity maps of the scalp between patients with migraine and healthy controls. Headache 2016, 57, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilaqua Gossi, D.; Chaves, T.C.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Moreira, V.C.; Canonica, A.C.; Florencio, L.L.; Bordini, C.A.; Speciali, J.G.; Bigal, M.E. Pressure pain threshold in the craniocervical muscles of women with episodic and chronic migraine: A controlled study. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2011, 69, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrøm, M.; Hagen, K.; Bjørk, M.H.; Stovner, L.J.; Gravdahl, G.B.; Stjern, M.; Sand, T. Sleep quality, arousal and pain thresholds in migraineurs: A blinded controlled polysomnographic study. J. Headache Pain 2013, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peńas, C.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Pareja, J.A. Generalized mechanical pain sensitivity over nerve tissues in patients with strictly unilateral migraine. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Pareja, J.A. Side-to-side differences in pressure pain thresholds and pericranial muscle tenderness in strictly unilateral migraine. Eur. J. Neurol. 2008, 15, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigós-Pedrón, M.; La Touche, R.; Navarro- Desentre, P.; Gracia-Naya, M.; Segura-Ortí, E. Widespread mechanical pain hypersensitivity in patients with chronic migraine and temporomandibular disorders: Relationship and correlation between psychological and sensorimotor variables. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholten-Peeters, G.G.M.; Coppieters, M.W.; Durge, T.S.C.; Castien, R.F. Fluctuations in local and widespread mechanical sensitivity throughout the migraine cycle: A prospective longitudinal study. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strupf, M.; Fraunberger, B.; Messlinger, K.; Namer, B. Cyclic changes in sensations to painful stimuli in migraine patients. Cephalalgia 2018, 39, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, D.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Jensen, R. Assessment of headache diagnosis. A comparative population study of a clinical interview with a diagnostic headache diary. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teepker, M.; Peters, M.; Kundermann, B.; Vedder, H.; Schepelmann, K.; Lautenbacher, S. The effects of oral contraceptives on detection and pain thresholds as well as headache intensity during menstrual cycle in migraine. Headache 2011, 51, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, E.L.H.; Padamsee, A. Menstrual-cycle and menstruation disorders in episodic vs chronic migraine: An exploratory study. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Racine, M.; Tousignant-Laflamme, Y.; Kloda, L.A.; Dion, D.; Dupuis, G.; Choinire, M. A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and experimental pain perception—Part 1: Are there really differences between women and men? Pain 2012, 153, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teepker, M.; Kunz, M.; Peters, M.; Kundermann, B.; Schepelmann, K.; Lautenbacher, S. Endogenous pain inhibition during menstrual cycle in migraine. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Yarnitsky, D. Experimental and clinical applications of quantitative sensory testing applied to skin, muscles and viscera. J. Pain 2009, 10, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, R.; Straker, L.; O’Sullivan, P.; Sterling, M.; Smith, A. Reliability of pressure pain threshold testing in healthy pain free young adults. Scand. J. Pain 2015, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.; Macdermid, J.; Nielson, W.; Teasell, R.; Chiasson, M.; Brown, L. Reliability, standard error, and minimum detectable change of clinical pressure pain threshold testing in people with and without acute neck pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2011, 41, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Wilgen, P.; Van der Noord, R.; Zwerver, J. Feasibility and reliability of pain pressure threshold measurements in patellar tendinopathy. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacourt, T.E.; Houtveen, J.H.; van Doornen, L.J.P. Experimental pressure-pain assessments: Test-retest reliability, convergence and dimensionality. Scand. J. Pain 2012, 3, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaguier, R.; Madeleine, P.; Vuillerme, N. Intra-session absolute and relative reliability of pressure pain thresholds in the low back region of vine-workers: Effect of the number of trials. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mailloux, C.; Beaulieu, L.D.; Wideman, T.H.; Massé-Alarie, H. Within-session test-retest reliability of pressure pain threshold and mechanical temporal summation in healthy subjects. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pubmed |

|---|

| #1 “Tension-Type Headache” [Mesh] #2 “Tension-Type Headache” #3 “Tension Headache” #4 “Stress Headache” #5 “Psychogenic Headache” #6 “Idiopathic Headache” #7 “Tension Vascular Headache” #8 “Tension-Vascular Headache” #9 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 #10 “Hyperalgesia” [Mesh] #11 “Hyperalgesia” #12 “Sensitization” #13 “Pain sensitivity” #14 “Pressure pain threshold” #15 “Algometry” #16 “Pain threshold” #17 #10 OR #11 Or #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 #18 #9 AND #17 ((“Tension-Type Headache”[Mesh]) OR (“Tension-Type Headache”[Title/Abstract] OR “Tension Headache” [Title/Abstract] OR “Stress Headache”[Title/Abstract] OR “Psychogenic Headache”[Title/Abstract] OR “Idiopathic Headache”[Title/Abstract] OR “Tension Vascular Headache”[Title/Abstract] OR “Tension-Vascular Headache”[Title/Abstract])) AND ((“Hyperalgesia”[Mesh]) OR “Hyperalgesia”[Title/Abstract] OR “Sensitization”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pain sensitivity”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pressure pain threshold”[Title/Abstract] OR “Algometry”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pain threshold”[Title/Abstract]) |

| Filters: Title/Abstract + Mesh→ Results: 247 |

| WOS |

| #1 TS = (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) #2 TS = (“Tension type headache” OR “tension-type headache” OR “idiopathic headache” OR “stress headache” OR “psychogenic headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension vascular headache” OR “tension-vascular headache”)#3 #1 AND #2 |

| Filters: Web of Science Core Collection→ Results: 488 |

| Scopus |

| TITLE-ABS (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND TITLE-ABS (“Tension type headache” OR “tension-type headache” OR “idiopathic headache” OR “stress headache” OR “psychogenic headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension vascular headache” OR “tension-vascular headache”) |

| Filters: TITLE-ABS→ Results: 268 |

| Medline (via EBSCO) |

| (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND (“Tension type headache” OR “tension-type headache” OR “idiopathic headache” OR “stress headache” OR “psychogenic headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension vascular headache” OR “tension-vascular headache”) |

| Results: 269 |

| Cinahl (via EBSCO) |

| (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND (“Tension type headache” OR “tension-type headache” OR “idiopathic headache” OR “stress headache” OR “psychogenic headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension vascular headache” OR “tension-vascular headache”) |

| Results: 129 |

| Pubmed |

|---|

| #1 “Migraine Disorders” [Mesh] #2 “Migraine with Aura” [Mesh] #3 “Migraine without Aura” [Mesh] #4 “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine” [Mesh] #5 “Migraine” #6 (“Migraine Disorders” [Mesh] OR “Migraine with Aura” [Mesh] OR “Migraine without Aura” [Mesh] OR “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine”[Mesh]) AND (“hyperalgesia”[Title/Abstract] OR “sensitization”[Title/Abstract] OR “pain sensitivity” [Title/Abstract] OR “pressure pain threshold” [Title/Abstract] OR “algometry” [Title/Abstract] OR “pain threshold”[Title/Abstract]) |

| Filters: Title/Abstract + Mesh→ Results: 571 |

| WOS |

| #1 TS = (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) #2 TS = (“Migraine Disorders” OR “Migraine with Aura” OR “Migraine without Aura” OR “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine”) #3 #1 AND #2 |

| Results: 112 |

| Scopus |

| TITLE-ABS (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND TITLE-ABS (“Migraine Disorders” OR “Migraine with Aura” OR “Migraine without Aura” OR “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine”) |

| Filters: TITLE-ABS → Results: 80 |

| Medline (via EBSCO) |

| (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND (“Migraine Disorders” OR “Migraine with Aura” OR “Migraine without Aura” OR “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine”) |

| Results: 740 |

| Cinahl (via EBSCO) |

| (“hyperalgesia” OR “sensitization” OR “pain sensitivity” OR “pressure pain threshold” OR “algometry” OR “pain threshold”) AND (“Migraine Disorders” OR “Migraine with Aura” OR “Migraine without Aura” OR “Ophthalmoplegic Migraine”) |

| Results: 323 |

| Study | Objective (In Relation to Pressure Pain Sensitivity) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Tool to Assess PPT | Patients with TTH (F/M) | Mean Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashina et al., 2005 [64] | To compare whether intramuscular and cutaneous pain sensitivity in cephalic region and in limb differs between patients with CTTH and healthy controls. | Patients with a diagnosis of CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988) and age between 18 and 65 years. | A history of more than one day with migraine per month; use of any kind of daily medication including prophy- lactic headache therapy but not oral contraceptives; excessive alcohol use; and serious somatic or psychiatric disorders. | Algometer Somedic | 20 14/6 | 46 |

| Bendtsen et al., 1996 [65] | To compare PPT and pressure pain tolerance thresholds between patients with CTTH and healthy controls | Patients with a diagnosis of CTTH according to ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). Patients with coexisting infrequent migraine (</= 1 day per month) | Patients suffering from serious somatic or psychiatric diseases and abusers of analgesics. | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 40 25/15 | 40 |

| Bovim, 1992 [7] | To compare PPT between patients with TTH, migraine, cervicogenic headache, and healthy controls. | Patients with a diagnosis of TTH according to ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | NR | Algometer PTH-AF2, Pain Threshold Meter. | 17 8/9 | 37 |

| Buchgreitz et al., 2006 [66] | To evaluate pain perception in primary headaches by combining investigation of tenderness by manual palpation, PPT and SR-functions in 1300 persons from the general population in Denmark. | Patients with a diagnosis of episodic TTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) in a large population living in Denmark. | Migraineurs with coexisting FETTH or CTTH. | Algometer Somedic | 108 70/38 | NR |

| Buchgreitz et al., 2008 [67] | To explore the cause-effect relationship between increased pain sensitivity (decreased PPT) and the development of headache between FETTH, CTTH, migraine and healthy controls. | Patients with a diagnosis of episodic TTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). All subjects who were still living in Denmark in 2001 and who were capable of answering written and verbal questions. | Migraineurs with coexisting FETTH or coexisting CTTH and subjects with coexisting migraine with FETTH and CTTH. | Algometer (Somedic) | 388 190/198 | 56 |

| Caamaño-Barrios et al., 2019 [44] | To compare PPT over symptomatic and distant pain-free nerve trunk areas between women with TTH and healthy controls | Consecutive women with a diagnosis of TTH according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013) | Chronic headaches; other primary/secondary headache including medication overuse headache; head/neck trauma (i.e., whiplash); cervical herniated disk or cervical osteoarthritis (medical records); any systemic degenerative disease; diagnosis of fibromyalgia; had received anesthetic blocks or any physical treatment in the previous six months; or pregnancy. | Algometer (Somedic) | 32 32/0 | 22 |

| Cathcart et al., 2008 [45] | To examine interactions between daily stress, pain sensitivity, and headache activity in CTTH sufferers. | Patients with a diagnosis of CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988) | NR | Mechanical algometer | 16 8/8 | 34 |

| De Cássia Correia Kälberer Pires et al., 2017 [9] | To estimate differences in PPT in cranio-cervical muscle TrPs between women with unilateral migraine or TTH, compared to asymptomatic women. | Women suffering from unilateral migraine, FETTH or CTTH lasting over a year according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Women with a previous history of neck trauma or whiplash, and those with other primary headaches and a history of headache lasting less than a year. | Dynamometer | 20 20/0 | 34 |

| Drummond et al., 2011 [46] | To determine whether the inhibitory effect of acute limb pain on pain to mechanical stimulation of the forehead is compromised in individuals with FETTH. | Individuals who reported at least 1 episode of headache per month for FETTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) | Individuals with a history of migraine and those who took prescribed medication to treat their headaches or any other medical condition. | Algometer | 34 23/11 | 22 |

| Engstrøm et al., 2014 [47] | To evaluate the relationship between sleep quality and pain thresholds (PPT) in healthy controls and TTH patients. | Subjects with ETTH or CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Subjects with known sleep disorders, coexisting frequent migraine, other major health problems or pregnancy, moderate or severe sleep apnoea defined as apnoea hypopnoea index (AHI). | Algometer (Somedic) | 20 11/9 | 41 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [11] | To investigate mechanical pain sensitivity distribution (PPT) over the trapezius muscle in patients with CTTH, strictly unilateral migraine and healthy controls. | Patients with a diagnosis of CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Participants with previous whiplash or neck trauma and other primary headaches, | Algometer (Somedic) | 20 20/0 | 39 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2008 [48] | To evaluate differences in PPT levels for the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) between patients with CTTH and controls; and | Patients with a diagnosis of CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | None of the patients fulfilled the criteria for other primary headaches, and there was no indication for secondary headaches based on history, physical, and neurological examinations. | Mechanical pressure algometer | 20 12/8 | 35 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [49] | To compare PPT in both cephalic and neck points between CTTH patients and healthy participants | Patients presenting with CTTH associated with pericranial tenderness according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Medication-overuse headache as defined by the IHS was ruled out in all cases | Pressure Threshold Meter, algometer | 25 12/13 | 41 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [50] | To analyze if the decrease in PPT was related to the presence of TrPs in the temporalis muscle in patients with CTTH and healthy controls. | Subjects with CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Patients with mixed headache. | Mechanical pressure algometer | 30 21/9 | 39 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [51] | To analyse if the decrease in PPT in the upper trapezius muscle was related to the presence of TrPs in the upper trapezius muscle in patients with CTTH and healthy subjects. | Subjects with CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Medication-overuse headache as defined by the IHS was ruled out in all cases | Mechanical pressure algometer | 20 9/11 | 36 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2008 [10] | To characterize hypersensitivity (decreased PPT) of the temporalis muscle in CTTH patients and healthy controls | Women with CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Other primary headaches | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 15 15/0 | 40 |

| Filatova et al, 2008 [52] | To investigate central sensitization in chronic headache with a variety of methods and compare this phenomenon across CM and CTTH. | Patients with IHS-defined CM, CTTH or mixed chronic headache, according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) | Age under 18 or over 65, the presence of peripheral neuropathy, dermato- logical disease, chronic pain in another location, major psychiatric disorder. | Hand-held pressure algometer | 25 23/2 | 39 |

| Jensen, 1995 [53] | To analyze the relative importance of central and peripheral nociceptive factors by assessing PPT and tolerance thresholds | Patients with TTH during at least 1 year, according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988), and age between 18 and 70 years. | Daily headache, migraine more than 1 day/month, cluster headache or trigeminal neuralgia, other neurological, somatic or psychiatric disorders, concurrent ingestion of major medications including migraine prophylactics, any form of drug abuse or dependency including large amounts of plain analgesics. | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 28 17/11 | 45 |

| Jensen et al., 1998 [54] | To compare the mechanical and the thermal pain sensitivity in TTH with and without disorders of pericranial muscles. | Patients with TTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). Duration of TTH for at least 1 year and age between 18 and 70 years. | Migraine more than 1 day per month; cluster headache; trigeminal neuralgia; other neurological, systemic, or psychiatric disorders; ingestion of major medications including prophylactics for migraine or other headaches; or any form of drug abuse or dependency such as daily ergotamine or large amounts of plain analgesics. | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 58 36/22 | 41 |

| Jensen et al., 1993 [55] | To evaluate the possible role of pericranial myofascial nociception (PPT) in headache pathogenesis. | Patients with CTTH diagnosis according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | Comorbid migraine attacks more than 30 days in the previous year | Pressure algometry | 158 96/62 | NR |

| Langemark et al., 1989 [56] | To compere the nociceptive thresholds of mechanical and thermal stimuli in patients with CTTH. | A history of TTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988) of at least 6 months duration and no more than 14 headache-free days/month. | Patients with a history of FM (more than one attack per month) | Pressure algometer | 32 22/10 | 40 |

| Malo-Urriés et al., 2020 [6] | To evaluate and compare sensory function in the trigeminocervical region in patients with CH, MH, and TTH and healthy controls. | Patients with headache according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013) for CH, MH, and TTH, respectively. | Other type of headache | Pressure algometer (Somedic) | 71 59/12 | 38 |

| Mazzotta et al., 1997 [57] | To confirm if chronic headache and migraine patients have a defect in the antinociceptive system by assessing PPT. | Patients with a diagnosis of ETTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | NR | Pressure algometer (Somedic) | 30 20/10 | 36 |

| Palacios Ceña et al., 2016 [8] | To compare differences in widespread PPT between women with FEETH, CTTH and healthy controls. | Patients with a diagnosis of FETTH or CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013). | (1) other primary/secondary headache; (2) medication overuse headache as defined by the ICHD-III; (3) cervical or head trauma; (4) pregnancy; (5) history of cervical herniated disk or cervical osteoarthritis; (6) any systemic degenerative disease, eg, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematous; (7) comorbid diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome; (8) receiving anesthetic block within the previous 6 months; or (9) receiving physical treatment previous 6 months. | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 92 92/0 | 47-48 |

| Peddireddy et al., 2009 [58] | To investigate whether jaw-stretch reflex and PPT of pericranial muscles in patients with CTTH differed from that of healthy individuals and between males and females | Subjects who had experienced headache > 16 days/month and with CTTH diagnosis according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) | NR | Handheld electronic algometer (Somedic) | 30 15/15 | 45 |

| Romero-Morales et al., 2017 [59] | To evaluate the MCDs in the PPTs of the temporalis and upper trapezius muscles in patients with and without TTH. | Individuals with TTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004), guidelines for TTH. | Diagnosis of migraine (>1 episode/month), diabetes, or fibromyalgia; surgery in the upper-limb or cervical regions; secondary headache; depression; neurologic or cardiovascular disease; temporomandibular disorders; pregnancy; or physical therapy treatment in the previous 6 months. Patients who were taking prophylactic or analgesic medication. | Mechanical algometer (FDK/FDN) | 60 32/28 | 36 |

| Sandrini et al., 1994 [60] | To address some of the current methodological limitations by comparing the results obtained with three different procedures in TTH, MH, and controls. | Subjects with CTTH or MH without aura patients (attacks frequency/range, 1-3/month), who were diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). Patients with an illness duration of more than 5 years. | NR | Electronic pressure algometer (Somedic) | 44 25/19 | 32 |

| Schoenen et al., 1991 [61] | To determine PPT in pericranial muscles as well as at an extracephalic site, the Achilles tendon, in patients with CTTH, migraineurs or healthy controls. | Females presenting with CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | Patients taking more than 3 analgesic tablets/week or treated with psychotropic drugs or patients who had taken such drugs less than 24 h before investigation. | Pressure algometer (Somedic) | 32 32/0 | 41 |

| Stroppa-Marques et al., 2017 [62] | To analyze the PPT of the SCM, SO, and UT muscles in individuals with ETTH. | Adults of both genders, ranging from 18 to 27 years of age, with ETTH according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Individuals with neurological or systemic diseases, previously diagnosed psychiatric disorders, cachexia, postural changes in treatment, lesions in the upper limb cingulum, diagnosis of CTTH or any other type of headache | Pressure dynamometer (algometer) (Kratos) | 30 21/9 | 20 |

| Uthaikhup et al., 2009 [63] | To investigate whether decreased PPT (hypersensitivity) were present in elders with different CTTH compared with elders without headache. | Patients diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Comorbid medical conditions that might interfere with pain measures. Patients with headache if they reported 2 or more types of headache or had headaches which had been diagnosed medically as secondary or associated with neurologic or systemic disorders. | Electronic algometer (Somedic) | 10 6/4 | 65 |

| Study | Objective (In Relation to Pressure Pain Sensitivity) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Tool to Assess PPT | Patients with MH (F/M) | Mean Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barón et al., 2016 [72] | To compare topographical PPT over the scalp in patients with MH, grouping them on episodic/chronic or unilateral/bilateral symptoms. | Patients with migraine diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013) | (1) other primary or secondary headaches, including medication overuse headache accordingly to the ICHD3 criteria; (2) history of neck or head trauma (i.e., whiplash); (3) pregnancy; (4) systemic disease, e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematous; (5) diagnosis of fibromyalgia; (6) previous treatment with botulinum toxin; or (7) anesthetic block within the past 3 months. | Mechanical algometer | 162 100/62 | 38-39 |

| Bevilaqua Grossi et al., 2011 [73] | To evaluate the cranio-cervical PPT values in women with EM and CM, relative to controls. | Women from 20 to 60 years with EM without aura or with CM, diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Other primary headaches, use of analgesic medication over the 24 h before the evaluation with pressure algometry medication overuse headache, women who reached a PPT value above the maximum permitted by the apparatus (20 kg) during calibration (palpation of the thenar region) and women diagnosed with neuropathic pain. | Digital manual dynamometer (DDK-10, Kratos) | 29 29/0 | 37 |

| Bovim et al., 1992 [7] | To compare PPT measurements between cervicogenic headache, migraine without aura, and TTH. | A diagnosis of TTH according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | NR | Algometer, PTH-AF2, Pain Threshold Meter. | 26 20/6 | 36 |

| Buchgreitz et al., 2006 [66] | To evaluate pain perception in primary headaches by combining investigation of tenderness by manual palpation, PPT and SR-functions in 1300 persons from the general population in Denmark. | A diagnosis of migraine according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). To live in Denmark. | Migraineurs with coexisting FETTH or CTTH. | Algometer | 60 42/18 | NR |

| Engstrøm et al., 2013 [74] | To compare subjective and objective sleep quality and arousal in migraine and to evaluate the relationship between sleep quality and pain thresholds (PT) in controls, interictal, preictal and postictal migraine. | Subjects with two to six episodes per month of migraine (M), with- (MA) and without aura (MwoA), diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Subjects with coexisting FM and TTH, other major health problems (sleep disease, hypertension, infection, neoplastic disease, neurological disease, CNS-implants, cardial or pulmonary disease), chronic or acute pain, regular use of neuroleptic, antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs, analgesics, or drugs for migraine prophylaxis the last four weeks), or subjects who were pregnant. | Algometer | 84 58/26 | 38 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [75] | To investigate differences in PPT in nerve trunks between patients with strictly unilateral migraine and healthy control participants; | A diagnosis of migraine according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Medication-overuse headache | Mechanical pressure algometer | 20 10/10 | 36 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2008 [76] | To analyse the differences in PPT and pericranial tenderness between patients with strictly unilateral migraine and healthy controls; | A diagnosis of migraine according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | NR | Pressure algometer | 25 17/8 | 32 |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [12] | To calculate topographical pressure pain sensitivity maps of the temporalis muscle in a blind design in patients with strictly unilateral migraine compared with controls. | Patients presenting the following features typical of migraine according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) | Other primary headaches | Pressure algometer | 15 15/0 | 36 |

| Filatova et al., 2008 [52] | To investigate central sensitization in chronic headache comparing CM and CTTH. | Patients with IHS-defined CM, CTTH or mixed chronic headache according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004). | Age under 18 or over 65, the presence of peripheral neuropathy, dermatological disease, chronic pain in another location, major psychiatric disorder. | Hand-held pressure algometer | 25 23/2 | 44 |

| Florencio et al., 2015 [14] | To investigate differences in PPT in the neck musculature between migraine patients and controls subjects. | Migraine patients diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013). | Subjects with other primary headaches; medication overuse head- ache; pregnancy; systemic degenerative diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematous, or other medical diseases affecting sensitivity, for example, such fibromyalgia or previous neck trauma (whiplash). | Digital manual dynamometer (DDK-10 Kratos) | 30 30/0 | 37 |

| Garrigós-Pedrón et al., 2019 [77] | To assess mechanical hyperalgesia in the trigeminal and extra-trigeminal region in patients with CM and TMD and to compare with a control group. | Diagnosis of CM according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013), and diagnosis of myofascial TMD, as defined by the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD). | Migraine crisis at the time of assessment, presence of other headache, another type of TMD, history of another chronic disease, history of neurological disease and/or dental problems and previous surgery or trauma to the upper body. | Analog algometer | 52 48/4 | 46 |

| Jensen et al., 1993 [55] | To evaluate the possible role of pericranial myofascial nociception in headache pathogenesis. | A migraine diagnosis according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). | Migraineurs with concurrent TTH more than 30 days in the previous year | Pressure algometry | 158 96/62 | NR |

| Palacios Ceña et al., 2016 [15] | To investigate widespread PPT women with EM, CM and healthy controls. | Women with migraine diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013). | 1, other primary or secondary headache, including medication overuse headache; 2, history of neck/ head trauma; 3, pregnancy; 4, cervical herniated disk or cervical osteoarthritis on medical records; 5, any systemic medical disease; 6, comorbid diagnosis of fibromyalgia; or, 7, anesthetic block in the past 3 months. | Electronic pressure algometer | 103 103/0 | 40-41 |

| Sales Pinto et al., 2013 [13] | To evaluate the influence of the concomitant presence of myofascial pain on the PPT values of masticatory muscles in women with a migraine. | Women, with ages ranging from 18 to 60 years, diagnosed with EM, according to the IHS criteria (NR). | Patients with only menstruation-related migraine, chronic migraine, other primary headaches, secondary headaches, or systemic conditions (eg, fibromyalgia) | Digital algometer (KRATOS) | 101 101/0 | NR |

| Sandrini et al., 1994 [60] | To address methodological limitations by comparing the results obtained from TTH, MH, and controls. | Subjects with CTH or MH without aura patients diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, first edition (1988). Patients with an illness duration of more than 5 years. | NR | Electronic pressure algometer | 44 25/19 | 32 |

| Scholten-Peeters et al., 2020 [78] | (1) To compare PPT during the preictal, ictal, postictal and interictal phases in people with migraine in both cephalic and extra-cephalic regions, and (2) To assess differences in mechanical sensitivity between people with migraine and healthy participants in both cephalic and extra- cephalic regions | People with migraine according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013), aged between 18 and 65 years and Dutch or English speaking. | Other types of headaches such as medication overuse headache, head or neck complaints within 2 months prior to the measurements, musculoskeletal painful conditions, psychiatric conditions, malignancy or other neuropathic pain states. Participants who received treatment for headache 48 h before the measurements or those who received botulinum toxin injections | Pressure algometer | 19 16/3 | 47 |

| Strupf et al., 2018 [79] | To find out if there are changes in pain thresholds and habituation between these groups and in a temporal association with migraine attacks and CTTH fluctuations. | Patients diagnosed with migraine with or without aura and CTTH according to the ICHD criteria, third edition (2013), with at least 15 headache days per month took part in the study. | NR | Electronic pressure algometer | 21 20/1 | 30 |

| Uthaikhup et al., 2009 [63] | To investigate whetherdecreased PTP (hypersensitivity) were different CTTH compared with elders without headache. | Patients diagnosed according to the ICHD criteria, second edition (2004) and the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group’s criteria for cervicogenic headache. | Comorbid medical conditions that might interfere with pain measures (inflammatory arthritis, fibromyalgia, neurologic symptoms, cognitive disturbance, or psychiatric disorders). Patients with headache if they reported 2 or more types of headache or had headaches which had been diagnosed medically as secondary or associated with neurologic or systemic disorders. | Electronic algometer | 26 18/8 | 66 |

| Ashina et al., 2005 [64] | Bendtsen et al., 1996 [65] | Bovim, 1992 [7] | Buchgreitz et al., 2006 [66] | Buchgreitz et al., 2008 [67] | Caamaño-Barrios et al., 2019 [44] | Cathcart et al., 2008 [45] | De Cássia Correia Kälberer Pires et al., 2017 [9] | Drummond et al., 2011 [46] | Engstrøm et al., 2014 [47] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [49] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [50] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [51] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2008 [10] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2008 [48] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [11] | Filatova et al., 2008 [52] | Jensen et al., 1993 [55] | Jensen, 1995 [53] | Jensen et al., 1998 [54] | Langemark et al., 1989 [56] | Malo-Urriés et al., 2020 [6] | Mazzotta et al., 1997 [57] | Palacios Ceña et al., 2016 [8] | Peddireddy et al., 2009 [58] | Romero-Morales et al., 2017 [59] | Sandrini et al., 1994 [60] | Schoenen et al., 1991 [61] | Stroppa-Marques et al., 2017 [62] | Uthaikhup et al., 2009 [63] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 1 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 1 |

| 2 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 2 | ||||||||

| 3 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | |||||||||

| C | 5 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 5 |

| 6 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 | |||||||||||||||||

| E | 7 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | ||||||||||||||

| 8 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | ||

| 9 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SC | L | H | H | H | H | H | L | H | L | H | H | L | L | L | L | L | H | L | H | H | H | L | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | L | ||

| Barón et al., 2016 [72] | Bevilaqua Grossi et al., 2011 [73] | Bovim, 1992 [7] | Buchgreitz et al., 2006 [66] | Engstrøm et al., 2013 [74] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2007 [76] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [12] | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al., 2009 [75] | Filatova et al., 2008 [52] | Florencio et al., 2015 [14] | Garrigós-Pedrón et al., 2019 [77] | Jensen et al., 1993 [55] | Palacios Ceña et al., 2016 [15] | Sales Pinto et al., 2013 [13] | Sandrini et al., 1994 [60] | Scholten-Peeters et al., 2020 [78] | Strupf et al., 2018 [79] | Uthaikhup et al., 2009 [63] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 1 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 1 |

| 2 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 2 | |||||||

| 3 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 3 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||||||||

| C | 5 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 5 |

| 6 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 | ||||||||

| E | 7 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | ||||||

| 8 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| 9 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| SC | L | H | H | H | H | H | L | H | H | L | L | L | H | H | H | L | H | L | SC | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Curiel-Montero, F.; Alburquerque-Sendín, F.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Rodrigues-de-Souza, D.P. Has the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Been Considered in Studies Investigating Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: A Scoping Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091251

Curiel-Montero F, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Rodrigues-de-Souza DP. Has the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Been Considered in Studies Investigating Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: A Scoping Review. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(9):1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091251

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuriel-Montero, Francisca, Francisco Alburquerque-Sendín, César Fernández-de-las-Peñas, and Daiana P. Rodrigues-de-Souza. 2021. "Has the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Been Considered in Studies Investigating Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: A Scoping Review" Brain Sciences 11, no. 9: 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091251

APA StyleCuriel-Montero, F., Alburquerque-Sendín, F., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Rodrigues-de-Souza, D. P. (2021). Has the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Been Considered in Studies Investigating Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: A Scoping Review. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091251