The New Empirical Equation Describing Damping Phenomenon in Dynamically Loaded Subgrade Cohesive Soils

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Revive

2.1. Identification of Factors Affecting Damping Ratio

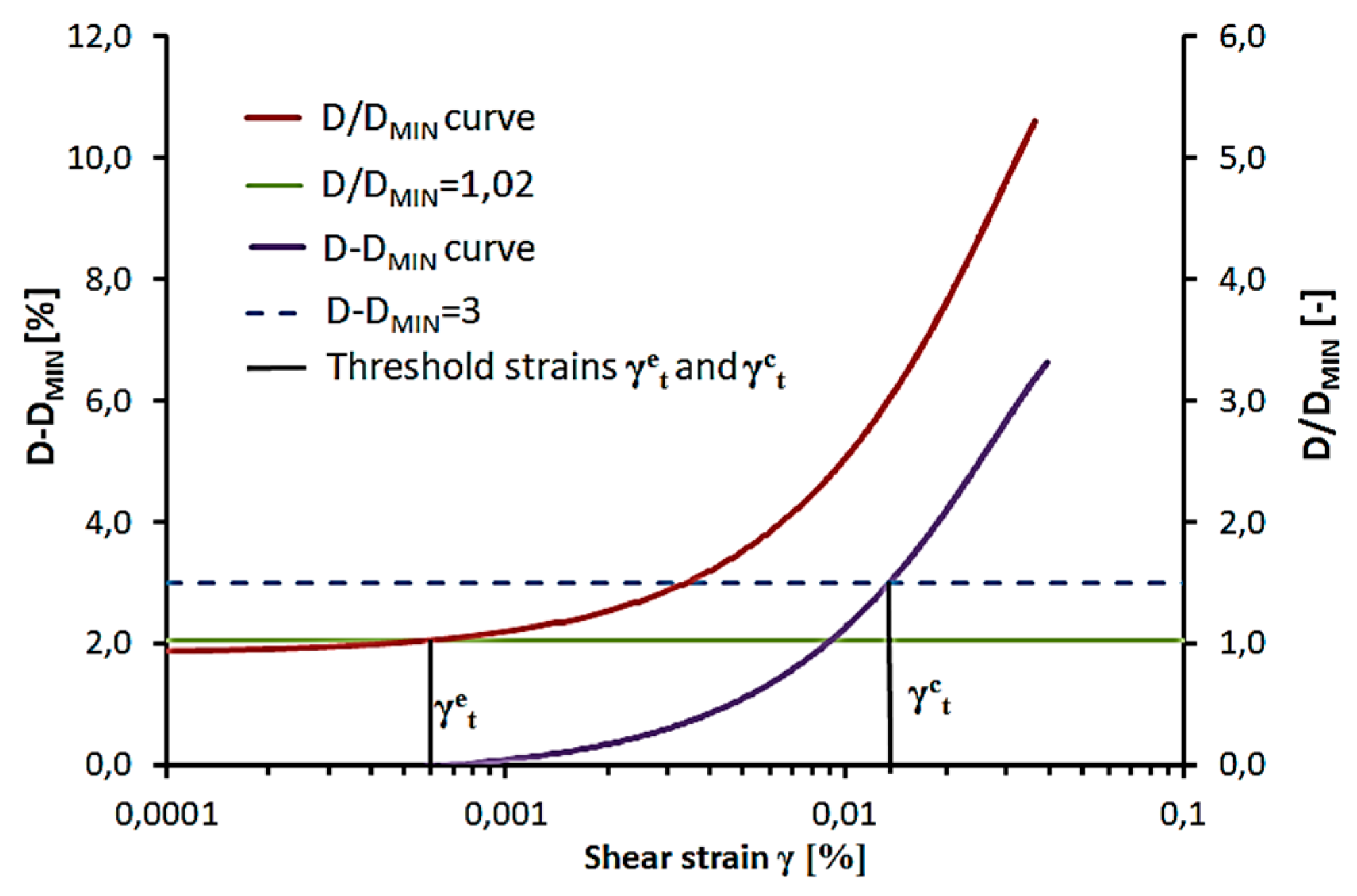

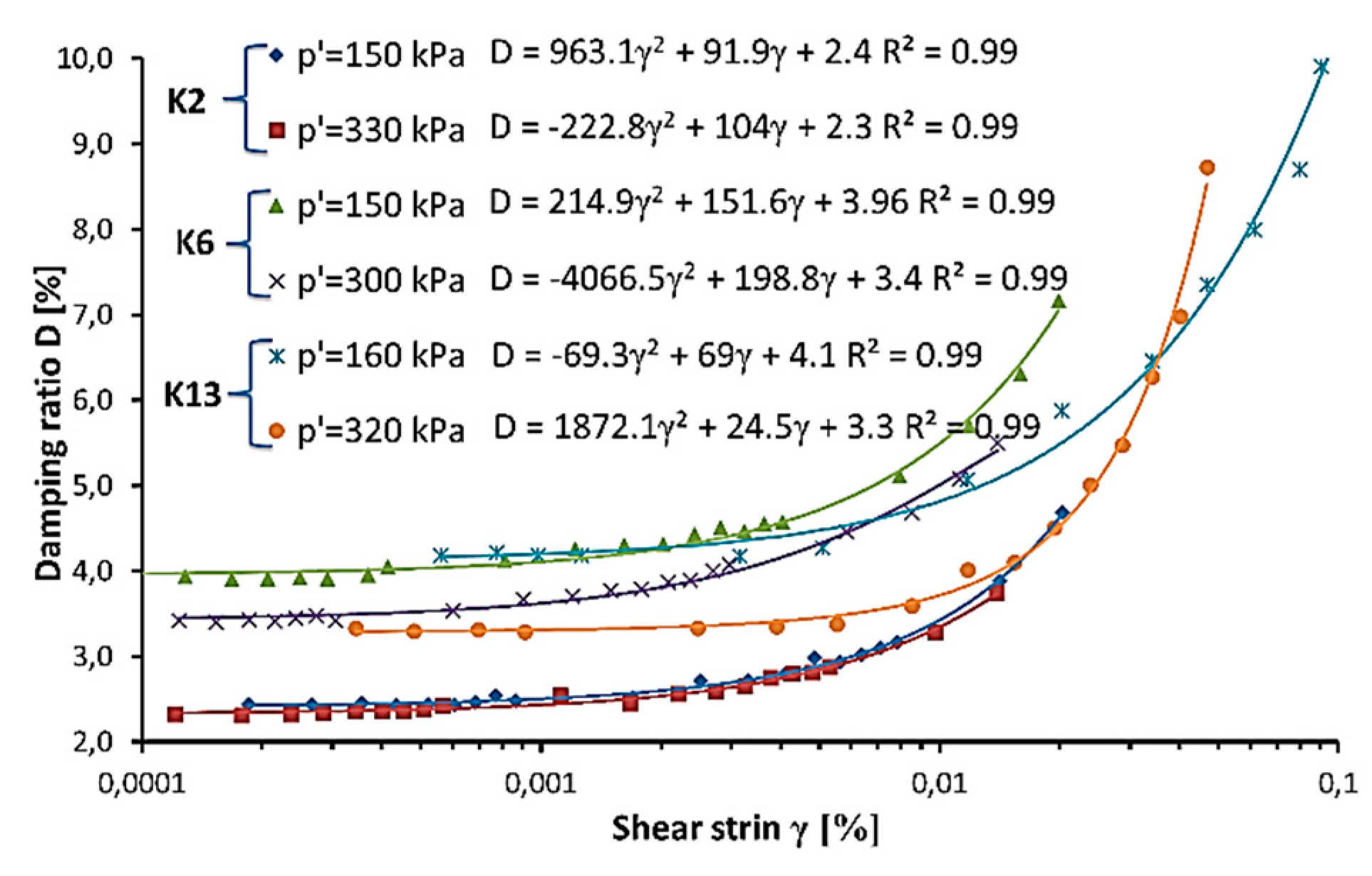

2.2. Shear Strain

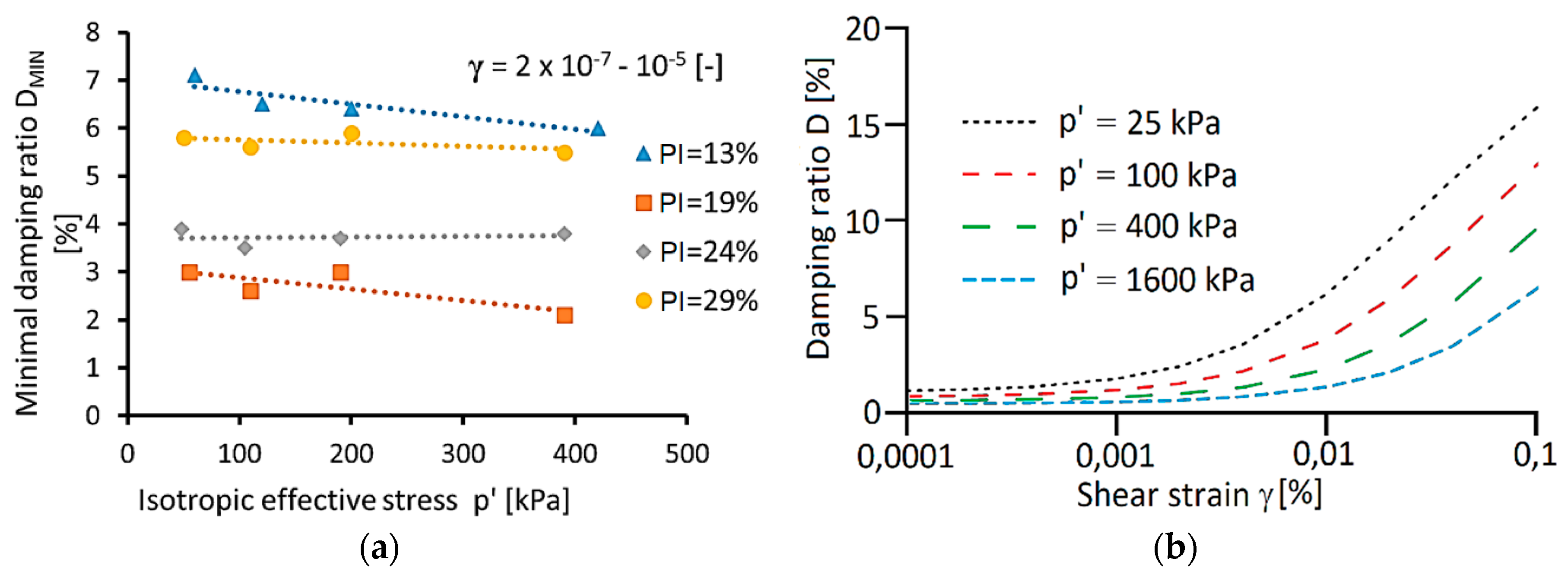

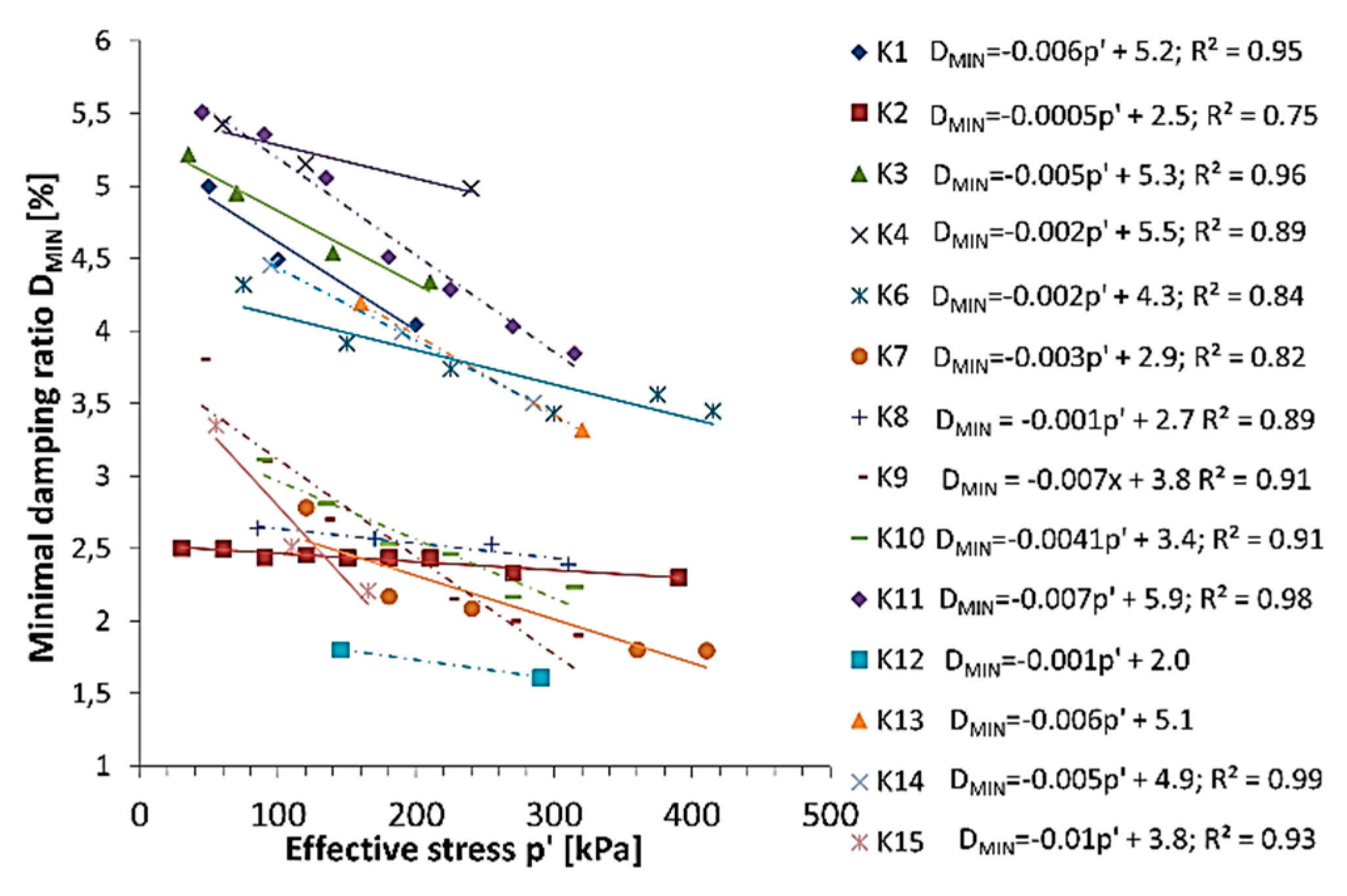

2.3. Effective Stress

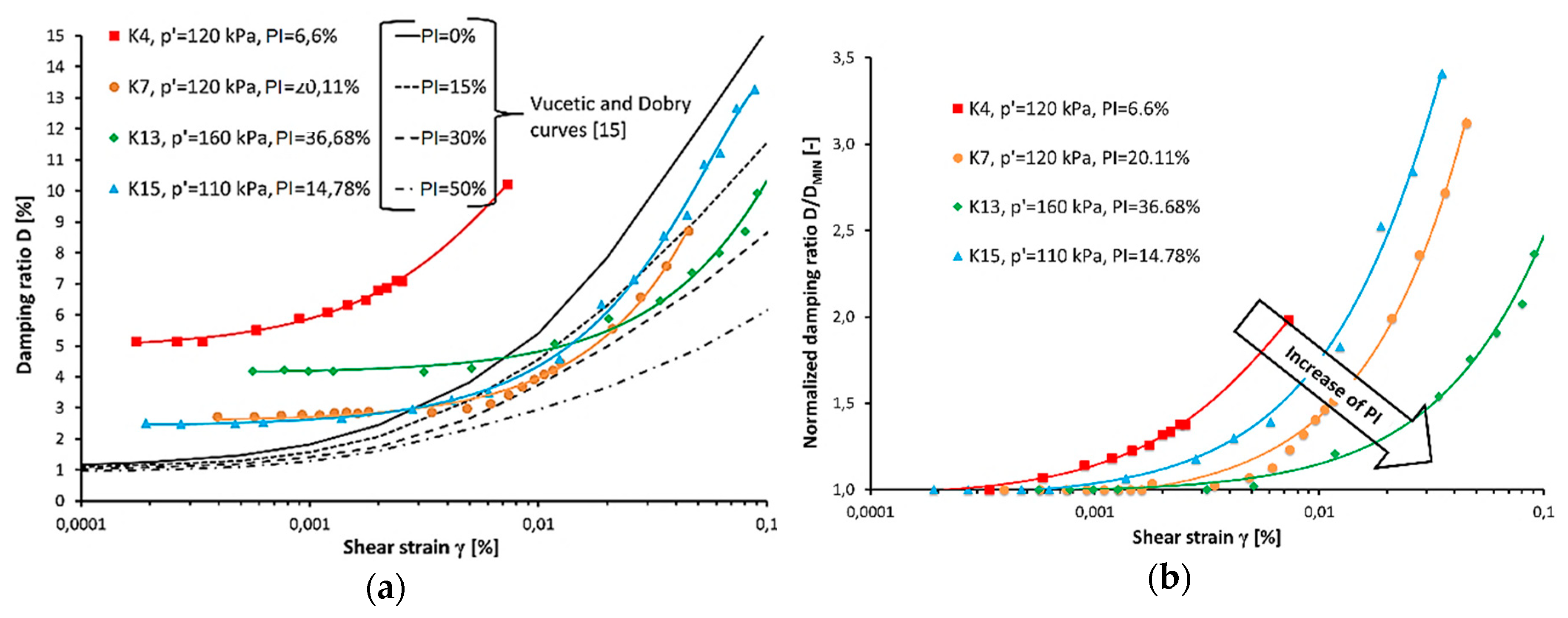

2.4. Soil Type—Plasticity Index (PI)

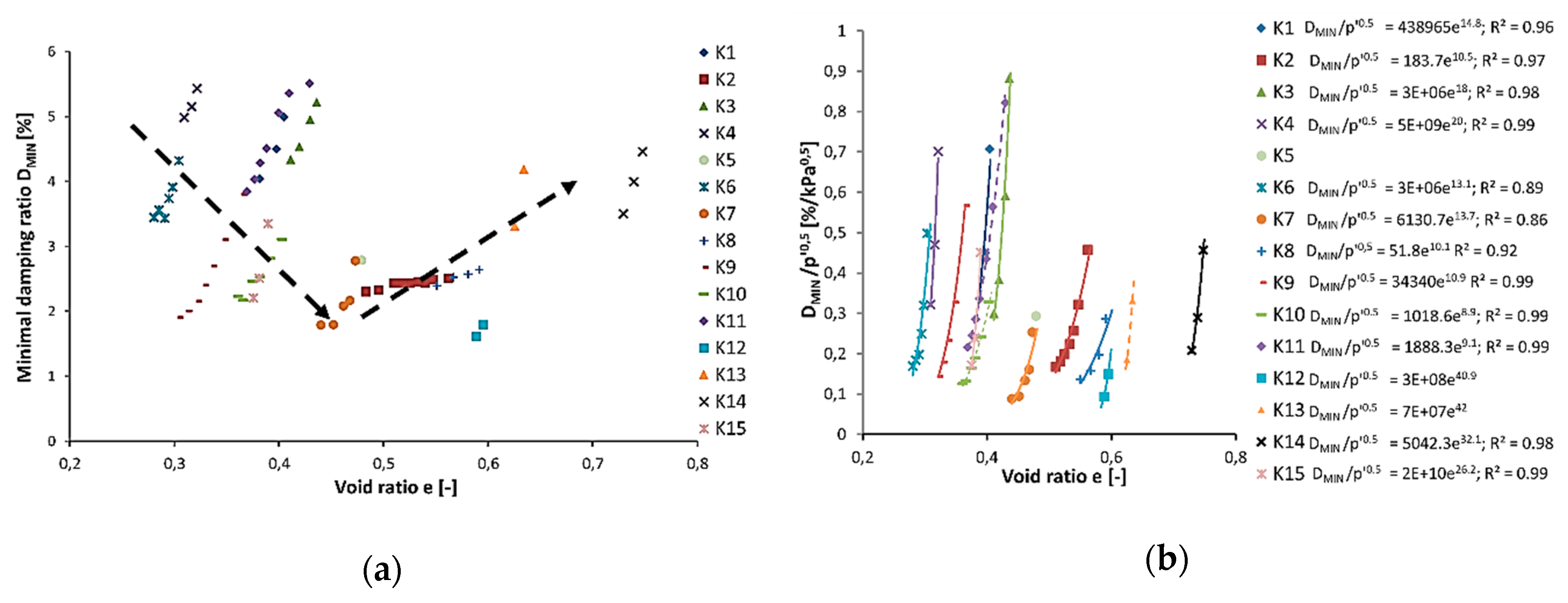

2.5. Void Ratio (e)

3. Materials and Methods

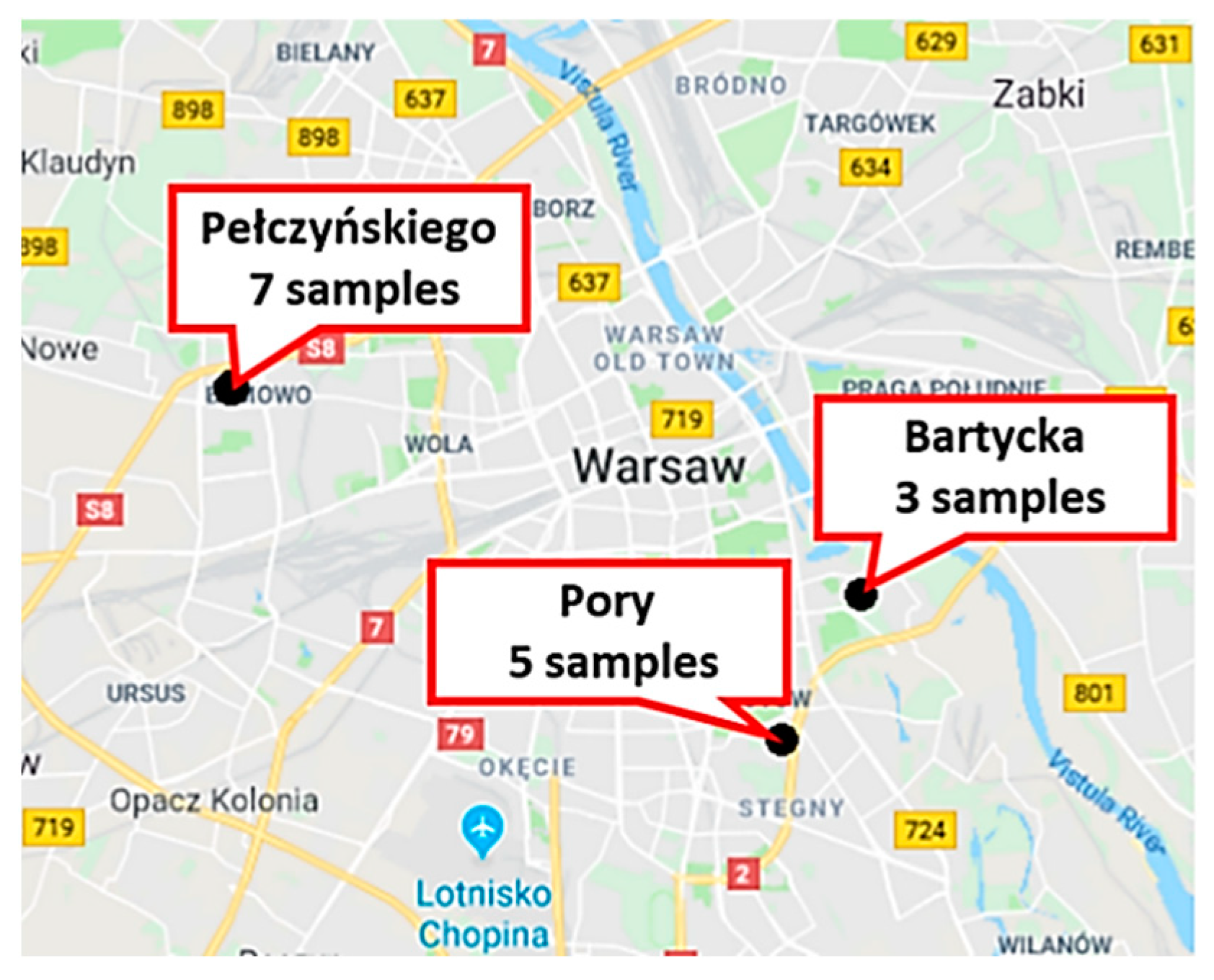

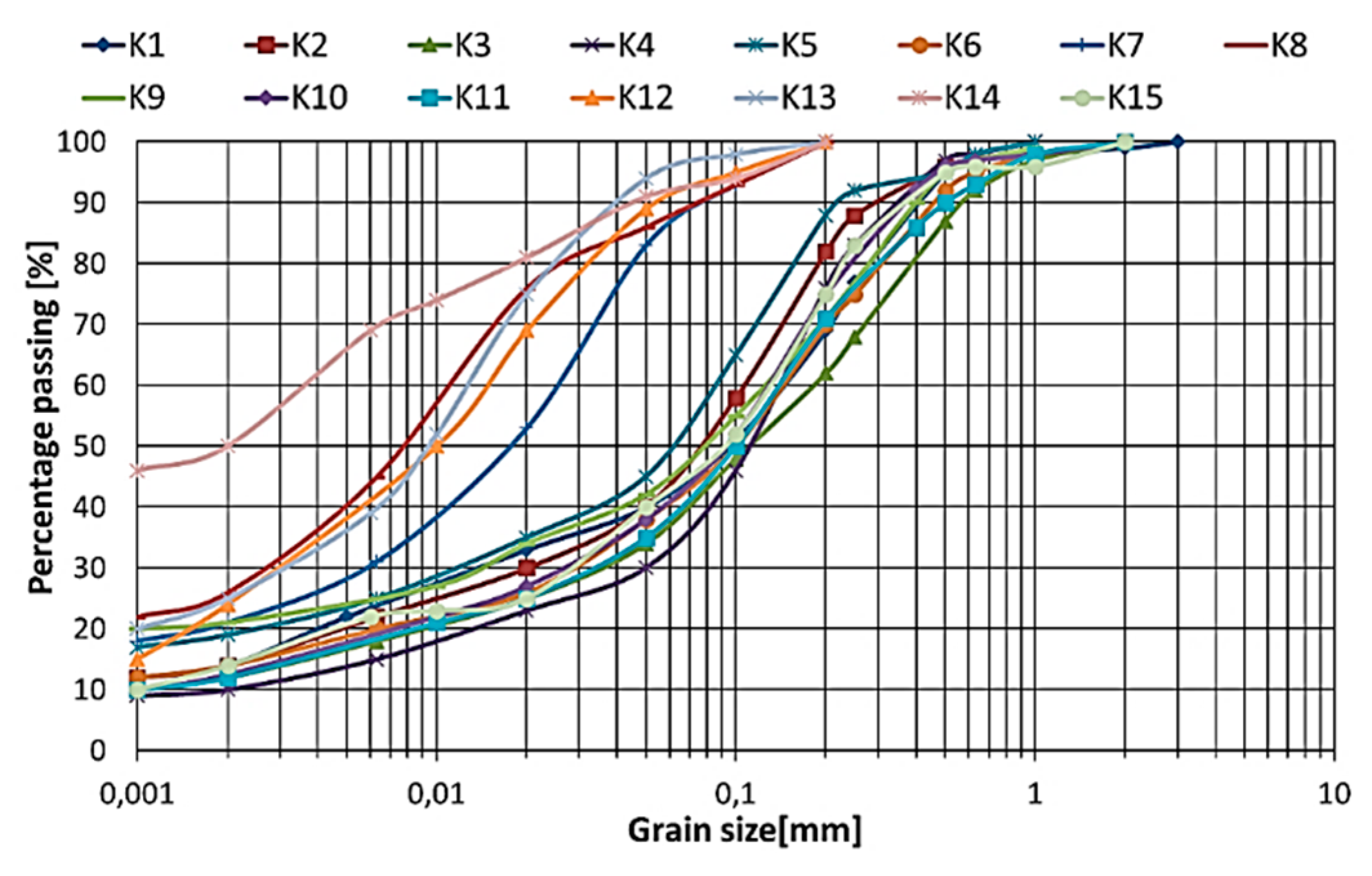

3.1. Soils’ Properties and Sample Preparation

3.2. Test Apparatus and Test Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Shear Strain

4.2. Effective Stress

4.3. Soil Type—Plasticity Index (PI)

4.4. Void Ratio (e)

4.5. Summary

5. Empirical Model

5.1. The Statistical Reliability of the Results

5.2. Experimental Model Describing the Damping Properties of Soil in the Range of Small and Medium Strains.

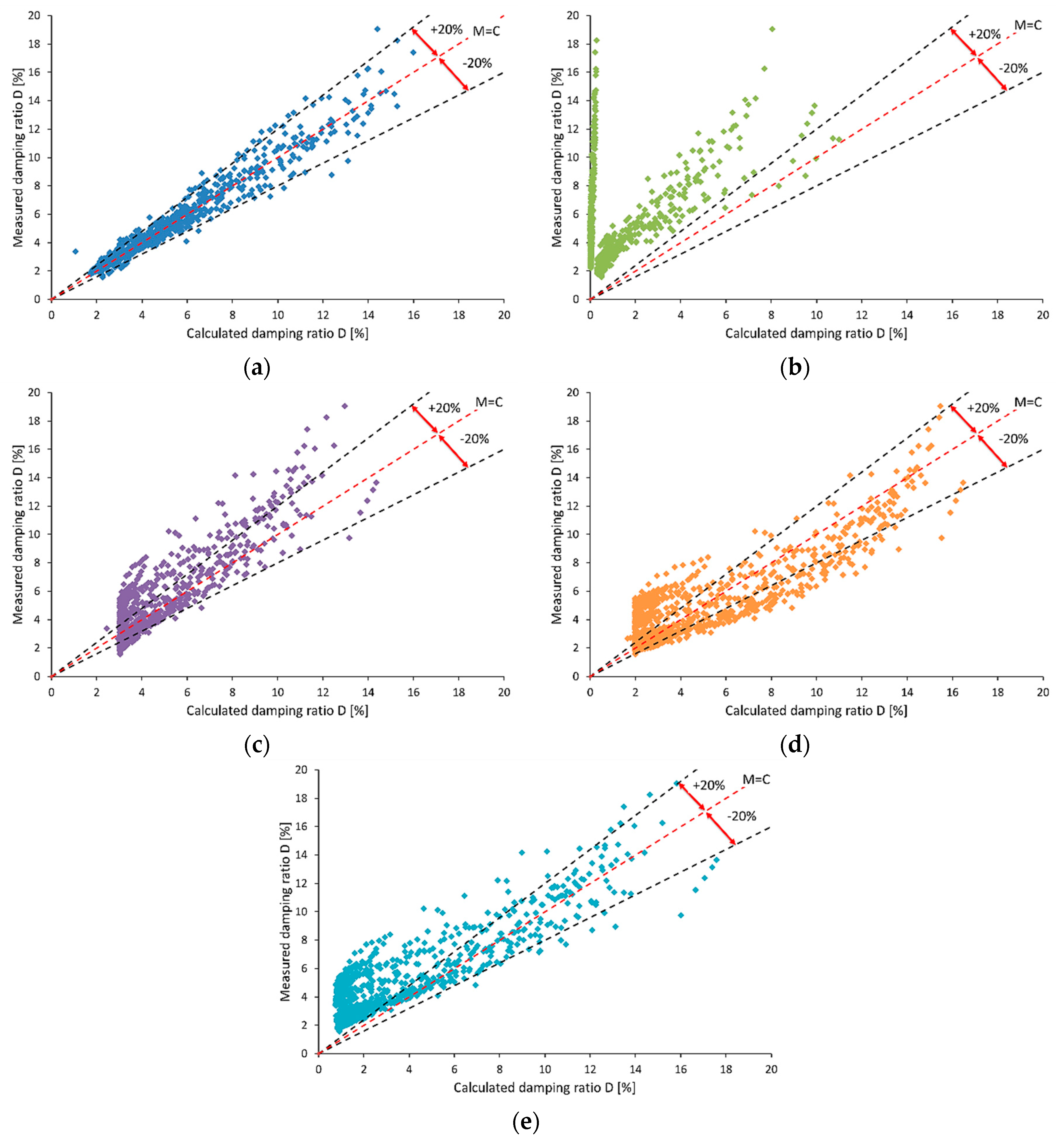

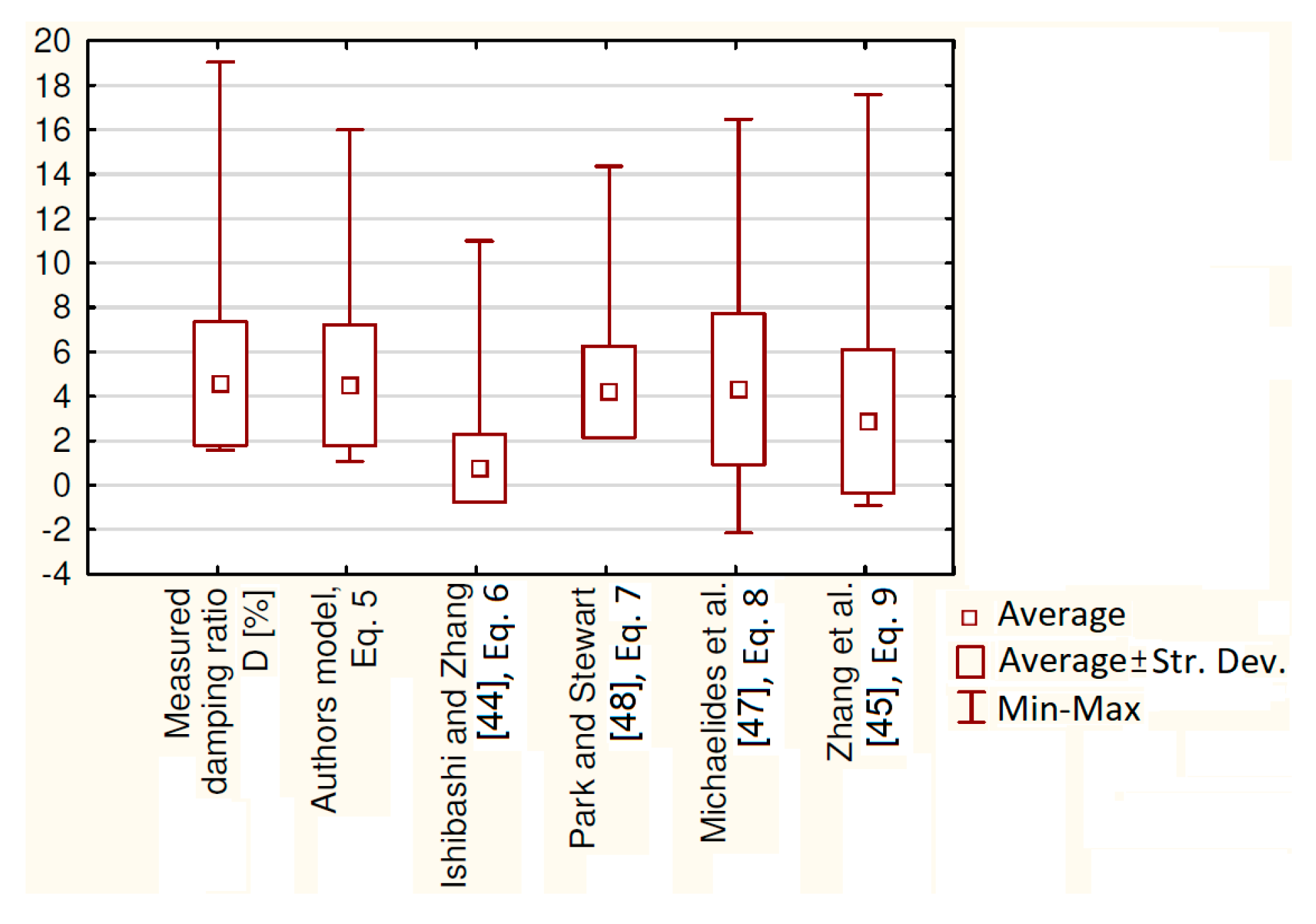

5.3. The Statistical Reliability of the Proposed Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araei, A.A.; Ghodrati, A. The Effect of Stress Induced Anisotropy on Shear Modulus and Damping Ratio of Mixed Sandy Soils. Indian Geotech. J. 2018, 48, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, D.S.; Nash, D.F.T.; Lings, M.L. Anisotropy of G0 shear stiffness in Gault Clay. Géotechnique 1997, 47, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrys, K.; Sas, W.; Sobol, E.; Gluchowski, A. Application of Bender Elements Technique in Testing of Anthropogenic Soil—Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Its Mixture with Rubber Chips. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payan, M.; Khoshghalb, A.; Senetakis, K.; Khalili, N. Small-strain stiffness of sand subjected to stress anisotropy. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 88, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beards, C. Structural Vibration: Analysis and Damping; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrys, K.; Sobol, E.; Sas, W.; Szymanski, A. Material damping ratio from free-vibration method. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. SGGW Land Reclam. 2018, 50, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, H.; Ammann, W.J.; Deischl, F.; Eisenmann, J.; Floegl, I.; Hirsch, G.H.; Klein, G.K.; Lande, G.J.; Mahrenholtz, O.; Natke, H.G.; et al. Vibration Problems in Structures: Practical Guidelines; Birkhauser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrys, K.; Sas, W.; Sobol, E.; Gluchowski, A. Torsional shear device for testing the dynamic properties of recycled material. Stud. Geotech. Mech. 2016, 38, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N. Seismic Ground Response Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.L. Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, B.O.; Black, W.L. Vibration modulus of normally consolidated clays. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1968, 92, 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, B.O.; Drnevich, V.P. Shear modulus and damping in soils: Measurement and parameter effects. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1972, 98, 603–624. [Google Scholar]

- Dobry, R.; Vucetic, M. Dynamic properties and seismic response of soft clay deposits. Proc. Int. Symp. Geotech. Eng. Soft Soils 1987, 2, 51–87. [Google Scholar]

- Darendeli, M. Development of a New Family of Normalized Moduli Reduction and Material Damping Curves. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, B.O.; Drnevich, V.P. Shear modulus and damping in soils: Design equations and curves. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1972, 98, 667–692. [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic, M.; Dobry, R. Effect of soil plasticity on cyclic response. J. Geotech. Eng. 1991, 117, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K. Soil Behaviour in Earthquake Geotechnics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, K.H., II; Darendeli, M.B.; Andrus, R.D.; Brown, L.T. Dynamic soil properties: Laboratory, field and correlation studies. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 21–25 June 1999; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 811–845. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, S.S.; Richart, F.E. Stress-history effects on shear modulus of soils. Soils Found. 1973, 13, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.C.; Novak, M. Dynamic properties of some cohesive soils of Ontario. Can. Geotech. J. 1981, 18, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, K.H., II; Hwang, S.K.; Lee, J.K.; Andrus, R.D. Effects of various parameters on the stiffness and damping of soils at small to medium strains. In Pre-Failure Deformation of Geomaterials, Proceedings of the International Symposium, Sapporo, Japan, 12–14 September 1994; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Volume 2.

- Kallioglou, P.; Tika, T.H.; Pitilakis, K. Shear modulus and damping ratio of cohesive soils. J. Earthq. Eng. 2008, 12, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrys, K.; Sas, W.; Sobol, E. Small-strain dynamic characterization of clayey soil. Acta Sci. Pol. Archit. 2015, 14, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mayoral, J.M.; Castanon, E.; Alcantara, L.; Tepalcapa, S. Seismic response characterization of high plasticity clays. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 84, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darendeli, M.B.; Stokoe, K.H.; Rathje, E.M.; Roblee, C.J. Importance of Confining Pressure on Nonlinear Soil Behavior and its Impact on Earthquake Response Predictions of Deep Sites, Proceedings of the International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering; Aa Balkema Publishers: Lisse, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 2811–2814. [Google Scholar]

- Towhata, I. Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, S.H. Dynamic Properties of Sand under True Triaxial Stress States from Resonant Column/Torsional Shear Tests. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.K.; Soga, K. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic, M. Soil properties and seismic response. In Proceedings of the 10th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Madrid, Spain, 19–24 July 1992; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 1199–1204, ISBN 9054100605. [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic, M. Cyclic threshold shear strains in soils. J. Geotech. Eng. 1994, 120, 2208–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborda, D.M. Development of Constitutive Models for Application in Soil Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Chen, G.X.; Zhou, E.Q. The dynamic shear modulus and the damping ratio of deep-seabed marine silty clay. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering (15WCEE), Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 1997-2:2007 Geotechnical Design—Part 2: Ground Investigation and Testing. Available online: http://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-1997-2-2007e.html (accessed on 14 March 2007).

- ISO 17892-4:2016 Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. Available online: http://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-iso-17892-4-2017-01e.html (accessed on 18 January 2017).

- ISO 17892-1:2014 Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 1: Determination of Water Content. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/55243.html (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- ISO 17892-12:2018 Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 12: Determination of Liquid and Plastic Limits. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72017.html (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- ISO 17892-5:2017 Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 5: Incremental Loading Oedometer Test. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/55247.html (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Sas, W.; Gabrys, K.; Szymanski, A. Experimental studies of dynamic properties of Quaternary clayey soils. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 95, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrys, K.; Sobol, E.; Markowska-Lech, K.; Szymanski, A. Shear Modulus of Compacted Sandy Clay from Various Laboratory Methods. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019; Volume 471, p. 042022. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. Standard Test Methods for Modulus and Damping of Soils by Resonant-Column Method; D4015-07; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.G.; Richart, F.E. Effects of straining on shear modulus of clays. ASCE J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1976, 102, 975–987. [Google Scholar]

- Kokusho, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Esashi, Y. Dynamic properties of soft clay for wide strain range. Soils Found. 1982, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, R.J. Some observations on the kinematic nature of soil stiffness. Soils Found. 1992, 32, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, I.; Zhang, X. Unified dynamic shear moduli and damping ratios of sand and clay. Soils Found. 1993, 33, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Andrus, R.D.; Juang, C.H. Normalized shear modulus and material damping ratio relationships. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.K.; Reddy, K.R. Dynamic Moduli and Damping Ratios for Monterey No. 0 Sand by Resonant Column Tests. Soils Found. 1989, 29, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, O.; Gazetas, G.; Bouckovalas, G.; Chrysikou, E. Approximate non-linear dynamic axial response of piles. Geotechnique 1998, 48, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Stewart, H.E. Suggestion of Empirical Equations for Damping Ratio of Plastic and Non-Plastic Soils Based on the Previous Studies. In Proceedings of the International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–31 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Importance to Damping Ratio, According to | Increasing Parameters | Effect on Damping Ratio, According to [13] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | [14] | |||

| Strain amplitude | *** | *** | Confining pressure (σ0) | Stays constant or decreases with σ0 |

| Effective stress | *** | *** | Void ratio (e) | Decreases with e |

| Void ratio | *** | * | Geologic age (tg) | Decreases with tg |

| Number of loading cycles | *** | ***+ | Cementation (c) | May decrease with c |

| Degree of saturation | - | * | Overconsolidation ratio | Not affected |

| Overconsolidation ratio | ** | * | Plasticity index (PI) | Decreases with PI |

| Frequency of loading | ** | ** | Cyclic strain (γc) | Increases with γc |

| Time effect | ** | - | Frequency of loading (f) | Stays constant or may increase with f |

| Grain characteristic | * | * | Number of loading cycles (N) | Not significant for moderate γc and N |

| Soil structure | * | - | ||

| Soil type and plasticity | - | *** | ||

| Test Site | Test No. | Depth (m) | Soil Type [33,34] | WC (%) | LL (%) | PL (%) | PI (%) | p’ (kPa) | e0 (-) | OCR (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartycka | K1 | 2.5 | saCl | 11.75 | 22.10 | 11.50 | 10.60 | 50–200 | 0.405 | 2.8–1 |

| K2 | 1.5 | sasiCl | 18.85 | 32.75 | 15.96 | 16.80 | 30–390 | 0.562 | 1.00 | |

| K3 | 1.7 | clSa | 14.43 | 21.20 | 12.24 | 8.96 | 35–210 | 0.436 | 1.00 | |

| Pełczyńskiego | K4 | 6.0 | clSa | 11.06 | 17.70 | 11.10 | 6.60 | 60–240 | 0.322 | 3.33–1 |

| K5 | 4.5 | sasiCl | 17.41 | 36.50 | 14.10 | 22.40 | 90 | 0.478 | 1.00 | |

| K6 | 7.5 | sasiCl | 10.76 | 24.50 | 12.47 | 12.03 | 75–415 | 0.304 | 2.13–1 | |

| Pory | K7 | 6.0 | siCl | 17.53 | 37.25 | 17.14 | 20.10 | 120-410–120 | 0.473 | 1–3.42 |

| K8 | 8.5 | siCl | 19.84 | 44.60 | 19.49 | 25.10 | 85–310 | 0.591 | 2–1 | |

| Pełczyńskiego | K9 | 2.2 | saCl | 12.23 | 37.00 | 11.45 | 25.60 | 45–315 | 0.365 | 1.00 |

| K10 | 2.2 | clSa | 15.57 | 41.70 | 14.26 | 27.40 | 90–315 | 0.403 | 1.00 | |

| K11 | 2.2 | clSa | 10.50 | 18.20 | 9.10 | 9.10 | 45–315 | 0.429 | 1.00 | |

| Pory | K12 | 7.2 | siCl | 21.98 | 51.27 | 23.65 | 27.60 | 145–290 | 0.595 | 1.38–1 |

| K13 | 8.0 | siCl | 22.95 | 63.50 | 26.82 | 36.70 | 160–320 | 0.634 | 1.25–1 | |

| K14 | 9.5 | Cl | 26.04 | 70.95 | 33.11 | 37.80 | 95–285 | 0.747 | 6.32–2.11 | |

| Pełczyńskiego | K15 | 2.7 | sasiCl | 12.68 | 27.10 | 12.32 | 14.80 | 55–165–55 | 0.389 | 1–3 |

| Test No. | p’ (kPa) | PI (%) | (%) | Test No. | p’ (kPa) | PI (%) | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | 50–200 | 10.60 | 0.0012 | n.e.* | K9 | 45–315 | 25.55 | 0.0018 | 0.014 |

| K2 | 30–390 | 16.79 | 0.0009 | 0.015–0.023 | K10 | 90–315 | 27.44 | 0.0008 | 0.0041–0.011 |

| K3 | 35–210 | 8.96 | 0.0008 | 0.007–0.014 | K11 | 45–315 | 9.10 | 0.0012 | 0.011–0.016 |

| K4 | 60–240 | 6.60 | 0.0005 | 0.0045 | K12 | 145–290 | 27.62 | 0.0019 | 0.022 |

| K5 | 90 | 22.4 | 0.0012 | 0.03 | K13 | 160–320 | 36.68 | 0.0024 | 0.04 |

| K6 | 75–415 | 12.03 | 0.0010 | 0.012–0.02 | K14 | 95–285 | 37.84 | 0.0011 | 0.007–0.02 |

| K7 | 120–410 | 20.11 | 0.0019 | 0.021–0.034 | K15 | 55–165 | 14.78 | 0.0013 | 0.013–0.022 |

| K8 | 85–310 | 25.11 | 0.0016 | 0.04 |

| No. | K1 | K2 | K3 | K4 | K5 | K6 | K7 | K8 | K9 | K10 | K11 | K12 | K13 | K14 | K15 | Avr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| I | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| W | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| M | 4.90 | 2.70 | 5.30 | 5.94 | 3.39 | 4.03 | 2.33 | 2.72 | 5.14 | 2.85 | 6.48 | 4.11 | 4.3 | 4.43 | 5.24 | - |

| SE | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| AE | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| RE | 3.55 | 4.41 | 2.61 | 2.64 | 1.53 | 2.66 | 1.42 | 3.67 | 1.94 | 2.00 | 1.31 | 2.23 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.44 | 2.29 |

| Low and Medium Cohesive Soil PI < 20% | Very Cohesive Soil PI > 20% | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI (%) | p’ (kPa) | e (-) | γ (%) | G/GMAX (-) | D (%) | PI (%) | p’ (kPa) | e (-) | γ (%) | G/GMAX (-) | D (%) | |

| PI (%) | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.44 | 1.00 | −0.13 | 0.58 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.27 |

| p’ (kPa) | 0.06 | 1.00 | −0.27 | −0.20 | 0.20 | −0.28 | −0.13 | 1.00 | −0.02 | −0.22 | 0.26 | −0.38 |

| e (-) | 0.65 | −0.27 | 1.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.28 | 0.58 | −0.02 | 1.00 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.07 |

| γ (%) | 0.00 | −0.20 | −0.04 | 1.00 | −0.88 | 0.85 | 0.07 | −0.22 | −0.07 | 1.00 | −0.83 | 0.88 |

| G/GMAX (-) | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.88 | 1.00 | −0.88 | −0.16 | 0.26 | 0.13 | −0.83 | 1.00 | −0.93 |

| D (%) | −0.44 | −0.28 | −0.28 | 0.85 | −0.88 | 1.00 | 0.27 | −0.38 | −0.07 | 0.88 | −0.93 | 1.00 |

| No. | Authors model, Equation (5) | Ishibashi and Zhang [44], Equation (6) | Park and Stewart [48], Equation (7) | Michaelides et al. [47], Equation (8) | Zhang et al. [45], Equation (9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | RE | AE | RE | AE | RE | AE | RE | AE | RE | |

| K1 | 0.22 | 4.7 | 4.51 | 93.3 | 1.54 | 31.4 | 2.03 | 42.9 | 3.39 | 70.8 |

| K2 | 0.26 | 7.7 | 2.45 | 85.0 | 0.56 | 20.4 | 0.25 | 18.6 | 1.19 | 48.7 |

| K3 | 0.46 | 7.3 | 5.53 | 96.7 | 2.34 | 39.8 | 2.69 | 48.7 | 4.15 | 74.2 |

| K4 | 0.68 | 10.5 | 5.96 | 97.1 | 2.42 | 39.8 | 2.33 | 43.2 | 4.03 | 68.3 |

| K5 | 0.17 | 4.6 | 3.07 | 76.4 | 0.00 | 3.8 | 0.25 | 20.8 | 1.15 | 42.3 |

| K6 | 0.23 | 5.0 | 4.09 | 93.9 | 1.00 | 21.8 | 1.43 | 36.4 | 2.91 | 69.2 |

| K7 | 0.21 | 7.4 | 2.18 | 77.9 | 0.80 | 36.0 | 0.63 | 21.4 | 0.83 | 40.6 |

| K8 | 0.33 | 11.8 | 1.24 | 66.8 | 1.42 | 78.8 | 0.87 | 38.8 | 0.39 | 34.6 |

| K9 | 0.49 | 7.7 | 3.20 | 60.6 | 0.02 | 22.5 | 1.05 | 25.8 | 0.38 | 25.4 |

| K10 | 0.57 | 11.1 | 2.00 | 64.4 | 0.86 | 21.4 | 0.83 | 31.5 | 0.10 | 58.5 |

| K11 | 0.52 | 6.7 | 7.18 | 93.2 | 2.35 | 30.9 | 1.14 | 28.3 | 3.05 | 49.7 |

| K12 | 0.77 | 18.4 | 2.78 | 59.1 | 0.04 | 31.9 | 0.88 | 19.0 | 0.61 | 22.1 |

| K13 | 0.70 | 13.3 | 1.93 | 46.9 | 0.18 | 10.9 | 0.38 | 30.7 | 0.78 | 39.8 |

| K14 | 0.61 | 14.2 | 2.83 | 64.4 | 0.83 | 18.3 | 0.92 | 32.0 | 2.16 | 51.5 |

| K15 | 0.46 | 8.9 | 5.46 | 84.2 | 0.96 | 15.5 | 0.18 | 20.3 | 1.42 | 35.2 |

| Avr. | 0.45 | 9.3 | 3.63 | 77.3 | 1.02 | 28.2 | 1.06 | 30.6 | 1.77 | 48.7 |

| R2 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.77 | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soból, E.; Głuchowski, A.; Szymański, A.; Sas, W. The New Empirical Equation Describing Damping Phenomenon in Dynamically Loaded Subgrade Cohesive Soils. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214518

Soból E, Głuchowski A, Szymański A, Sas W. The New Empirical Equation Describing Damping Phenomenon in Dynamically Loaded Subgrade Cohesive Soils. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214518

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoból, Emil, Andrzej Głuchowski, Alojzy Szymański, and Wojciech Sas. 2019. "The New Empirical Equation Describing Damping Phenomenon in Dynamically Loaded Subgrade Cohesive Soils" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214518

APA StyleSoból, E., Głuchowski, A., Szymański, A., & Sas, W. (2019). The New Empirical Equation Describing Damping Phenomenon in Dynamically Loaded Subgrade Cohesive Soils. Applied Sciences, 9(21), 4518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214518