Abstract

Mobility is a significant robotic task. It is the most important function when robotics is applied to domains such as autonomous cars, home service robots, and autonomous underwater vehicles. Despite extensive research on this topic, robots still suffer from difficulties when moving in complex environments, especially in practical applications. Therefore, the ability to have enough intelligence while moving is a key issue for the success of robots. Researchers have proposed a variety of methods and algorithms, including navigation and tracking. To help readers swiftly understand the recent advances in methodology and algorithms for robot movement, we present this survey, which provides a detailed review of the existing methods of navigation and tracking. In particular, this survey features a relation-based architecture that enables readers to easily grasp the key points of mobile intelligence. We first outline the key problems in robot systems and point out the relationship among robotics, navigation, and tracking. We then illustrate navigation using different sensors and the fusion methods and detail the state estimation and tracking models for target maneuvering. Finally, we address several issues of deep learning as well as the mobile intelligence of robots as suggested future research topics. The contributions of this survey are threefold. First, we review the literature of navigation according to the applied sensors and fusion method. Second, we detail the models for target maneuvering and the existing tracking based on estimation, such as the Kalman filter and its series developed form, according to their model-construction mechanisms: linear, nonlinear, and non-Gaussian white noise. Third, we illustrate the artificial intelligence approach—especially deep learning methods—and discuss its combination with the estimation method.

1. Introduction

Mobility is a basic feature of human intelligence. From the beginnings of robot technology, people have been imagining building a human-like machine. Smart movement is an obvious feature of a robot and an important manifestation of its intelligence. Self-moving of a robot mainly includes navigation and control, such as perceiving the surrounding environment, knowing where it wants to go and where it is at a given time, and further controlling its movement and adjusting the travel path to reach its destination. In this review, we focus only on the navigation, that is, the robot’s awareness of where it is in relation to the surrounding environment.

When we walk on the street, we can see that a car is moving and that the leaves on a tree are moving because of wind. Fortunately, we know that the house will not move. Although we see the house moving backward as our forward movement proceeds, we also know that the house is not moving. According to our position relative to that of the house, we also can judge our speed and that of the car, predict the location of the car, and determine whether we need to avoid the car.

For robots, the so-called mobile intelligence means that they can move in the same manner as human beings and exercise the same judgment. A robot on a road, for example, an autonomous car, needs to answer three questions constantly during movement: where am I, where am I going, and how do I go? It first needs to judge its movement relative to all other kinds of movement (cars, trees, and houses in the field of vision) and then has to avoid other cars. Among these tasks, the ability to understand surroundings is critical. The performance of an autonomous car heavily depends on the accuracy and reliability of its environmental perception technologies, including self-localization and perception of obstacles. For humans, these actions and judgments are dominated by human intelligence, but for machines, they are extremely complex processes.

We first define robotic mobile intelligence. When moving, a robot should have two basic capabilities: (1) to localize itself and navigate; and (2) to understand the environment. The core technologies enabling these capabilities are denoted as simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), tracking, and navigation. SLAM constructs or updates the map of an unknown environment while simultaneously keeping track of the robot’s location. It is a complex pipeline that consists of many computation-intensive stages, each performing a unique task. Tracking refers to the automatic estimation of the trajectory of a target as it moves. The tracking algorithms are based mainly on estimation theory. Here, the target is a general one, either the robot itself or others. When the robot wants to “track itself”, which means that the robot wants to know its own motion, called “navigation”, by which the robot determines its own position and direction of movement.

We now define foreground and background targets. We usually set the target to track as a foreground target, such as the cars. The house does not need to be tracked, nor do other stationary objects, so it is set as the background. Some mobile aspects that do not need to be tracked, such as the movement of leaves, are called background targets. The most difficult aspect of video tracking is to distinguish the difference between foreground and background targets.

In current navigation systems, researchers are trying to replicate such a complicated process by using a variety of sensors in combination with information processing. For example, vision sensors are commonly used sensors in robotic systems. In the video from a camera fixed on a robot moving on the street, the houses are moving, the cars are moving, and even the trees on the roof have their own motion because of the robot’s own movement. How to obtain the mobile relationship between the robot and foreground target from so many moving targets has always been an area of intense research interest. The optical flow method [1] is a widely used method to determine this relationship, which assumes that the apparent velocity of the brightness pattern varies smoothly almost everywhere in an image. Researchers have done much useful work in this area [2,3].

The disadvantage of the optical flow method is the large computational overhead. Moreover, it is difficult to find the correct optical flow mode when the robot is moving at a high speed. To overcome such a difficulty inherent in a visual sensor, other sensors have been introduced, for example, inertial measurement units (IMUs) and global positioning systems (GPSs), into the navigation system. GPSs are now widely used in cars [4]. In most cases, GPSs provide accuracy within approximately 10–30 m. For autonomous cars, however, this accuracy is insufficient.

IMUs have become smaller, lower cost, and consume less power thanks to miniaturization technologies, such as micro-electro-mechanical systems or nano-electro-mechanical systems. Because the measurements of the IMUs have unknown drift, it is difficult to use the acceleration and orientation measurements, to obtain the current position of a pedestrian in an indoor navigation system [5]. Combined with video sensors, IMUs have been used in indoor and outdoor seamless navigation connection, such as in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) [6].

Other sensors, such as Wi-Fi [7,8], have been widely used in indoor navigation systems in recent years. Wi-Fi uses triangulation to locate a target, which can keep the indoor positioning error within tens of meters and effectively overcome the IMU position drift. Another sensor used for indoor positioning is ultra-wide-band (UWB) [9], which requires the user to place the receiver in the area of target activity.

Considering these factors, it is clear that the navigation systems are complex. In the process of movement, a robot must first perceive the surrounding environment firstly, and then need to know the way and speed of movement of itself and a target. It also needs to judge the movement of a foreground target and predict whether it will collide with it. Fortunately, some progress has been made in research on autonomous vehicles. Unmanned vehicles driving on roads can identify road signs, traffic conditions, and so on.

Robot navigation uses a tracking algorithm [10,11,12,13] to achieve maneuvering target estimation. Based on the known characteristics of the system noise, the estimation method extracts the estimated trajectory of a target from an uncertain signal. To obtain good estimation results, two models are crucial, namely, the process and measurement models. The process model, which describes the motion characteristics of maneuvering targets has been a hot topic in the field of target tracking. Based on a variety of different motion characteristics and using Newton’s law, many modeling methods for maneuvering models have been presented [14,15,16,17] that capture the characteristics of most moving targets.

However, at present, the research methods based on estimation still cannot deal with all the complicated situations in practical applications. The main reason is that it is difficult to obtain an accurate measurement model of a sensor used in different applications. For example, the drift of IMU data is still a subject that needs further study [18]. In visual tracking applications, the interference of light, sunlight, and flexible objects makes the target information obtained by the image-processing method less accurate and extremely computationally intensive [19,20].

The fact that we want robots to behave like human beings, and because a robot’s motion space and behaviors are increasingly complicated, brings great difficulties to the application of the traditional estimation-based tracking algorithms. We believe the reason that a robot system cannot cope with such a complex environment space and motion behavior, is that the information collected by sensors has a high degree of uncertainty because of the complexity of environment. In other words, we cannot accurately model the measurement model.

In our opinion, an estimation-based algorithm has a strong theoretical foundation and can obtain good kinematic analysis of moving targets. Therefore, these theories are still of great value for robotics in very complicated environments. However, in the face of increasingly complex environments and movements, the most important difficulty lies in the fact that a sensor cannot obtain the accurate information in response to the complex environment of the outside world. Therefore, a method of modeling the measurement sensor should be developed. Based on the traditional equation-based measurement model, a networked model representing the relationship among the various data should be considered to deal with these complex environments.

In this survey, we discuss the basic theory of a traditional tracking algorithm applied to a navigation system under the condition of analyzing the complex environments, as well as the factors affecting system performance in complex environments. In addition, we review the necessity, feasibility, and the method of using artificial intelligence method for navigation systems to achieve the mobile intelligence. Furthermore, we propose an the initial idea of how to apply a current artificial intelligence (AI) method to enhance the intelligence of a robot motion system.

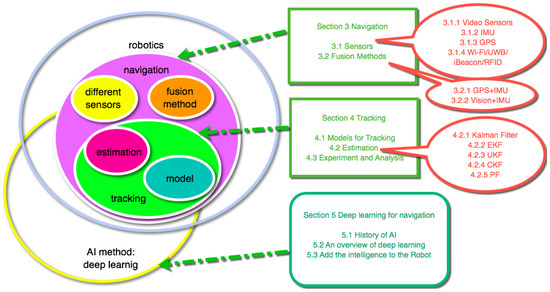

2. Survey Organization

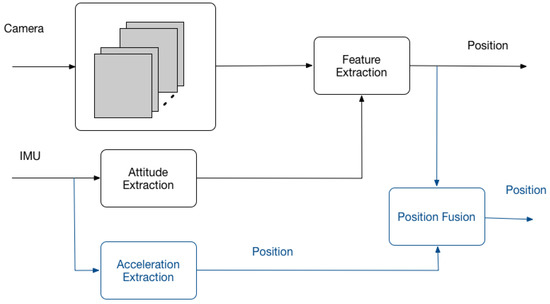

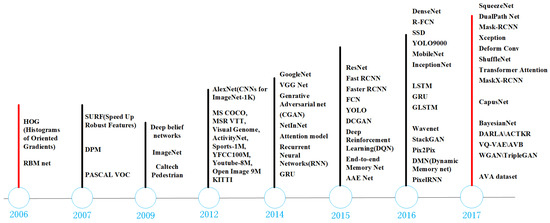

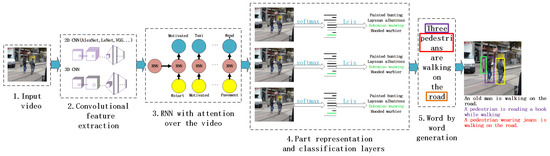

Figure 1 shows the organization of this survey. We first focus on robotics research, especially the mobile intelligence. Regarding navigation, Section 3.1 discusses the sensors applied in the robot system, such as video sensors, IMU, GPS, Wi-Fi, and UWB. In Section 3.2, we illustrate the methods for fusing information collected by multiple sensors, including GPS or vision, together with IMU. Section 3.2 also introduces other multi-sensor systems, such as IMU and Wi-Fi.

Figure 1.

The organization of this survey.

As the basis algorithm of the navigation, tracking models and methods are very important. Section 4.1 discusses some representative models, including the Singer model, interacting multiple model (IMM), the adaptive model, etc., which are the most widely used models. In particular, we believe that the tracking methods are the most important part of navigation, so Section 4.2 details the estimation methods, including the extended Kalman Filter (EKF), unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), cubature Kalman Filter (CKF), and particle filter (PF).

Finally, as the most important part of this review, Section 5 introduces the deep learning applied to navigation. In addition to the typical network of deep learning, we also discussed how to combine deep learning with the estimation method to improve a robot’s mobile intelligence.

4. Tracking

4.1. Models for Tracking

Target tracking has always been a hot topic in many application fields, and it is the basic algorithm in navigation systems. The displacement, velocity, acceleration, and other motion characteristics of the maneuvering target are estimated by using the data measured by the sensor.

In the 1970s, researchers were interested in target tracking technology [74], which had many military and civilian applications, such as missile defense, ocean surveillance, and so on.

In a tracking problem, two aspects are very important: the system models and the estimation method. The former includes the process model and the measurement model.

Accurate estimation requires accurate process models. For example, when radar tracks a target, the human action or control command of the driver at any time will make the target turn, dodge and execute other actions in the course of target movement. To obtain enough information about the trajectory tracking performance of the target, it is necessary to use the correct motion model of the maneuvering target to perform the estimation.

Some process models have been proposed for the tracking of a maneuvering target. The constant-velocity (CV) models emphasize that accelerations are very small with the so-called white-noise acceleration model. This model assumes that the target acceleration is an independent process (strictly white noise), such as , where is the acceleration noise. The most attractive feature of this model is its simplicity.

The second simple model is the so-called constant-acceleration (CA) model or, more precisely, the “nearly-constant-acceleration model”. This model assumes that the derivative of acceleration is the Gaussion white-noise as , where is the noise of the derivative of acceleration.

Since the Singer model was put forward in 1970 [14], researchers have advanced the “current” statistical model, and IMM, among other maneuvering target models. The Singer model models target acceleration as a first-order semi-Markovian process with zero mean, which is in essence an a priori model because it does not use online information for the target maneuvering, although it can be made adaptive through an adaptation of some parameters. Because of the complexity of the objectives of an actual track, any a priori model cannot be extremely effective for the diverse acceleration situations of actual target maneuvers. One of the main shortcomings of the Singer model is that the target acceleration has zero mean at any moment. Another shortcoming is that it cannot use online information.

An acceleration model, called the current statistical model [15] is, in essence, a Singer model with an adaptive mean—that is, a Singer model modified to have a nonzero mean of the acceleration. In this current model, the model can use online tracking information, and the priori (unconditional) probability density of the acceleration is replaced by a conditional density, (i.e., Rayleigh density). Clearly, this conditional density carries more accurate information and is better able to be used than the a priori density. We note that this conditional Rayleigh assumption was made for the sole purpose of obtaining the variance of the acceleration prediction.

Based on those models, there are many modified models for maneuvering target tracking, but all of them need a prior hypothesis. Because the tracking systems are of different types, the prior hypothesis is sometimes inappropriate. In general, we call the Singer model, the current statistical model, or the Jerk model as the ‘state’ model, and they have one common problem, that they all assume the maneuvering target possesses a particular set of movement characteristics. However, the noise characteristics of the actual maneuvering target will change, and the model that exhibits good tracking performance in the previous period may no longer maintain good performance.

The IMM models the change of the system dynamics as a Markovian parameter having a transition probability [16]. According to the filter results, the consistency between each model and the current actual maneuvering target is estimated, and then the estimated results are generated by weighting the estimation of each model, so that the tracking performance is better than that of any single model. However, when the maneuvering target exhibits complex motion, the IMM model suffers heavy computational burden. On the other hand, the limited number of the model can not still catch all the system dynamics feature.

Another model, called the adaptive model, assumes that no a prior information about the system noise is known, which must therefore be estimated based on the estimation of state [17]. Based on the basic idea that the model will effect the measurement data, and the measurement data contain the information of the model, the adaptive model describes system dynamics based on the measurement data on the condition that the system equation structure is given.

Most researchers agree that the disadvantage of the “state” model is the requirement of the given system parameter, which can not be known exactly. Although IMM and the adaptive model have tried the best to catch the maneuvering characteristics of a target, the model still seems to be insufficiently accurate in the practical system, especially when the system is complex.

The authors believed that the reasons are as follows: Firstly, the matrix form of the ‘state’ model can not contain enough parameters to describe the complex dynamics. For example, the process matrix of adaptive model [17] only has nine parameters, although they are adjusted each step online, the amount of information is insufficient.

Secondly, the structure of the model is too simple to describe the complex movement. The CV, CA, Singer model, the current statistical model as well as the Jerk model are all with a basic linear structure, and only the IMM and adaptive model have switched nonlinear structure between different models, but they still can not catch the complexity of the practical system. More complex network of non-linear structure is very necessary. In Section 5, we will explain why network-structured models can capture complex information and even make tremendous progress in pattern recognition.

4.2. Estimation

Estimation means that the desired state is obtained based on measurements undergoing the effects of noise, disturbance and, uncertainty. For a navigation system, many methods are used to estimate the state, including the Kalman filter, EKF, UKF, CKF, and PF. We introduce these methods in order, detail the relationship between them and their characteristics, and compare the performance of their algorithm. Owing to length considerations, the specific steps of the algorithms are listed in Appendix A Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3.

Even readers already familiar with these estimation methods will benefit from the information in this section; for newcomers to robot navigation research, this information should prove to be significant. Our focus is on the algorithm itself, and we succinctly explain the origin of the algorithm, while avoiding complex algorithmic deductions; the goal is to enable algorithmic engineers to quickly learn and use algorithmic processes.

4.2.1. Kalman Filter

A Kalman filter can estimate the state of a linear system based on the system model. First, we consider two system models: the measurement model and the process model. The measurement model describes the relationship between the desired state and the measurement. The linear measurement model is expressed as follows:

where is the measurement, is the desired state, is the measurement matrix, and is the measured noise .

The estimated state is often variable, so it is necessary to consider the transfer mode of the state, which is called as the process model, which is generally expressed as the following with the linear transfer mode of the state

where is the process matrix and is the process noise. It is clear that the characteristics of process noise and measurement noise play a crucial role in the performance of estimation methods. The simplest linear system is that the process noise and measurement noise are both Gaussian noise with a zero mean with a given covariance of and , respectively.

To obtain the estimated state for such systems, a Kalman filter [75] is one of the most widely used estimation methods. Theoretically, a Kalman filter is an estimator for what is called the linear-quadratic problem, which is the problem of estimating the state of a linear dynamic system. The resulting estimator is statistically optimal with respect to any quadratic function of estimation error [76,77]

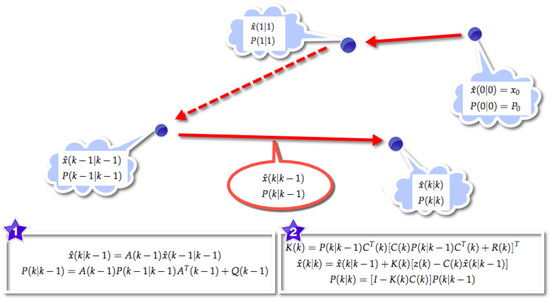

According to these equations, details of the Kalman filter algorithm are presented in Figure 6, in which it is evident that it works in a two-step process from the initial value . In the first step, denoted the prediction step, the Kalman filter produces prediction estimates along with their uncertainties from the last estimate . The second step is the update step. Once the outcome of the next measurement, , is obtained, the estimates are updated using a filter gain based on .

Figure 6.

Illustration of Kalman filter. From an initial value , two steps are used to obtain the final estimate: (1) Prediction step. The Kalman filter produces prediction estimates along with their uncertainties from the last estimate , where is the process matrix and is the covariance of process noise. (2) Update step. The estimates are updated using a filter gain based on and , where is the measurement matrix and is the covariance of measured noise.

4.2.2. EKF

The first nonlinear filtering algorithm, EKF, was developed on the basis of the theory of Kalman filtering. In this method, the Taylor expansion of a nonlinear function is used to retain the first-order linearization, and other high order terms are omitted to approximate the nonlinear function [78].

The details of the EKF algorithm are shown in Table A1, compared with a standard Kalman filter. The prediction and update of the state and covariance of both filters are listed. We can see the system to which the EKF is applied is nonlinear with the system models and .

Owing to the Taylor expansion, EKF can deal with the nonlinear characteristics of the system and has been used in many applications. In Ref. [10], an extended Kalman filter was used to estimate the speed of a motor based on the measured quantities, such as stator currents and direct current link voltage. The estimated speed was used for vector control and overall speed control. To obtain the stable and convergent solutions, a weighted global iteration procedure with an objective function is proposed for stable estimation and is incorporated into the extended Kalman filter algorithm [79].

Regarding the navigation system, the EKF was designed for the online estimation of the speed and rotor position by only using measurements of the motor voltages and currents [80]. The EKF algorithms allow efficient computation compared with other nonlinear estimation methods. A quaternion based EKF was developed to determine the orientation of a rigid body from the outputs of IMUs [11].

An EKF is commonly applicable to the system with weak nonlinearity, because of the Taylor expansion only to the first order. If the nonlinearity of the system is strong, there will be a large difference between the approximate linear system of the Taylor expansion and the original nonlinear system. This leads to a decrease of estimation performance or even the filter divergence.

Because of its small amount of calculation, an EKF is apt for application in a practical system. Marins et al. [81] presented an extended Kalman filter for real-time estimation of rigid body orientation using an IMU. Different than the work in Ref. [11], the Gauss-Newton iteration algorithm was utilized in Ref. [81] to find the best quaternion that relates the measured accelerations and Earth’s magnetic field in the body coordinate frame to calculate values in the Earth’s coordinate frame. The best quaternion is used as part of the measurements for the Kalman filter. As a result, the measurement equations of the Kalman filter become linear, and the computational requirements are significantly reduced, making it possible to estimate the orientation in real time. Yang and Baum [82] presented a method of tracking an elliptical shape approximation of an extended object based on a varying number of spatially distributed measurements. Based on an explicit nonlinear measurement equation about the kinematic and shape parameters, an EKF was derived for a closed-form recursive measurement update.

4.2.3. UKF

To increase the nonlinear processing ability of estimation methods, Uhlmann and Julier proposed a UKF based on the idea of “approximating the probability density distribution of the system random variable to make the approximation of nonlinear function easier” [12,83]. According to the prior probability distribution of the state, a set of sigma points is determined and their corresponding weighted values are calculated. The sigma point is then taken as an independent variable to calculate the dependent variable of the known nonlinear function, and the mean and covariance are estimated by calculating the dependent variable. The UKF algorithm also inherits the Kalman filtering framework, and exhibits better nonlinear estimation performance than the EKF because the UKF does not need to calculate the Jacobi (Jacobian) matrix of a nonlinear system and reduces the difficulty of the calculation process.

However, in practical applications, UKF is widely used in systems with lower state dimensions. Once the system state reaches higher than three dimensions, the covariance matrix is obtained by an unscented transform (UT) to be a non-positive definite matrix, and the filter accuracy decreases rapidly.

Regarding the system model shown in Table A2, the UT selects 2n + 1 sigma points as the following:

where , and denotes the row of matrix *, and k is a constant [12].

The 2n + 1 weights are

the nonlinear transfer by the nonlinear measurement equation is expressed as

and the mean and the covariance are expressed as

Table A2 details the UKF estimation method. The sigma points used for the prediction of the state with the weights, and the update of the state with the filter gain, are shown in this table. Finally, the prediction and update processes for the covariance are also listed.

4.2.4. CKF

The CKF was proposed by Simon Haykin and Ienkaran Arasaratnam [13]. This algorithm also inherits the Kalman filtering framework, and uses the numerical integration method of the spherical-radial cubature rule to approach the Gaussian integral. Similar to the UKF, the CKF also selects a set of point sets, and passes the selected point set through the nonlinear function, and then approximates the Gaussian integral in the filtering of the nonlinear system through a series of calculations. The CKF also avoids the large error caused by linearization of nonlinear functions by the EKF algorithm. It can handle any nonlinear system, and it does not depend on the specific equation of nonlinear function in the process of filtering. Unlike the UKF, the CKF algorithm used the spherical-radial cubature rule and Bayesian estimation to approximate the integral nonlinear Gaussian filter.

Regarding the system model shown in Table A3, the third-degree spherical-radial cubature rule selects 2n cubature points as follows:

where , and means the ith row of matrix *, and the 2n weights are

the nonlinear transfer by the nonlinear measurement equation is expressed as

and the mean and the covariance are expressed as

where is the covariance of the measurement noise .

Until now, we have dealt with three filters to solve the estimation problem for nonlinear systems and determine which performs best. Much research has been done on the performance of these three nonlinear estimation filter. Hong-de et al. [84] considered an EKF, UKF, and CKF for the tracking of a ballistic target to estimate its position, velocity, and the ballistic coefficient, with the conclusion that the UKF and CKF both have higher accuracy and less computational cost than the EKF. Ding and Balaji [85] compared a UKF and a CKF for two radar tracking applications, namely, high-frequency surface wave radar (HFSWR) and passive coherent location (PCL) radar. The simulation showed that the UKF outperformed the CKF in both radar applications, using performance measures of root-mean-square error and normalized estimation error squared, and further concluded that the CKF is not as well suited as UKF to highly nonlinear systems, such as PCL radar. A similar conclusion was reached in Ref. [86] for bearings-only tracking (BOT) problem. Pesonen and Piché [87] compared a UKF and CKF using an extensive set of positioning benchmarks, including real and simulated data from GPS and mobile phone base stations, and resulting in conclusion that in tested scenarios no particular filter in this family is clearly superior.

Therefore, although the CKF was developed later than the UKF, we find that it does not have the obvious advantages of UKF. Recently, some developed nonlinear estimation methods have been proposed, but most are based on the fundamental principle of a UKF or CKF. For example, from the numerical-integration viewpoint, a sampling points set was derived by orthogonal transformation of the cubature points in Ref. [88]. By embedding these points into the UKF framework, a modified nonlinear filter, designated a transformed unscented Kalman filter (TUKF), is derived. The TUKF purportedly can address the nonlocal sampling problem inherent in the CKF while maintaining the virtue of numerical stability for high dimensional problems. Dunik et al. [89] pointed out that traditional filters providing local estimates of the state, such as the EKF, UKF, or CKF, are based on computationally efficient but approximate integral evaluations, and therefore proposed a general local filter that utilizes stochastic integration methods providing the asymptotically exact integral evaluation with computational complexity similar to the traditional filters.

From all of these research works, we conclude that the UKF and CKF are the popular estimation methods for the nonlinear systems, because they all have efficient computation speeds and nonlinear processing ability. However, for nonlinear highly complex problems, the performance of both filters still must be improved.

4.2.5. PF

All of the noted Kalman filters deal only deal with the Gaussian noise in the process model and measurement model. Another filter, the so-called PF, can handle the case of non-Gaussian noise [90]. The PF is a combination of the Monte Carlo integral sampling method and the Bayesian filtering algorithm, and its advantage is that it can be used to deal with any nonlinear and non-Gaussian estimation problem. It has been proven that the ideal estimation accuracy can be achieved as long as the number of particles is sufficient. Although the PF algorithm was proposed some time ago, it has not undergone substantive development because it has some problems, specifically the following: With increase of computational iterative PF algorithms, the PF has only one or a few particle weights close to 1, and most of its particle weights are almost 0, with the problem being the particles facing degradation. Moreover, to solve the particle degradation problem effectively, it is necessary to use the method of resampling—that is, the removal of particles of lower weight and the replicating of particles with higher weight [91,92,93].

However, this method destroys the diversity of particles, and makes the particle filter again face another important problem, namely, the lack of samples, which leads to a decrease of the filter’s estimation performance. Therefore, researchers have devised many solutions to these problems, including several variants of the particle filter (e.g., sampling importance resampling filter, auxiliary sampling importance resampling filter, and regularized particle filter) within a generic framework of the sequential importance sampling algorithm [94]. In Ref. [95], an enhanced particle swarm optimized particle filter was proposed together with a noninteracting multiple model, which can be efficiently applied in the modern radar maneuvering target tracking field efficiently.

Table 2 details the performance of all the Kalman filters and the PF, and it can be seen that the classical Kalman filter can be used only for a linear system with a Gaussian process and measurement noise, and, furthermore, that EKF, UKF, and CKF can deal with nonlinear systems accompanied by Gaussian noise. Moreover, the PK can be used in any system, although with high computational complexity.

Table 2.

The difference of state estimation method.

4.3. Experiment and Analysis

In this Section, we use experiments to show these two points: one is that the estimation method relies heavily on the accuracy of the models. If the model is not accurate enough, the estimating results can not get high performance. The other is that for the complex nonlinear system, none of the above mentioned filters, such as EKF, UKF, CKF and even PF, has outstanding advantage, and their performance still needs further improvement.

Here, the simulated 2D RFID tracking system developed in [43] was used as the experiment platform, which described a typical nonlinear estimation problem. The RFID readers were placed in the specific area and the measurement space of each reader with high detection rate were shown with circles (from inside to outside in contour map) in Figure 7. In the white area of the figure, the distance information of the target can only be obtained with low detection rate. The reference trajectory of the target is given with ‘black’ as terisk.

Figure 7.

The measurement space of RFID readers and the reference trajectory. Note: The unit of each axes is meter.

The tracking covariance was defined as , where and are the estimation covariance of horizontal and longitudinal axes, respectively.

4.3.1. Case One

In this case, the CV, CA, Singer model, current model, IMM and the adaptive model were compared. The tracking covariance of each model with UKF estimation method is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison on tracking covariance of different models with UKF estimation method.

It is noted that the covariances of the IMM and adaptive model are relatively small comparing with other models, and the CV model get the worst covariance. It is because that the trajectory generated by the simulated RFID tracking system has higher-order dynamic feature and complexity.

On the other hand, the covariances of the IMM and adaptive model obtained via the simulated system are much smaller than that in the practical system. This is because, on the one hand, the practical tracking case is more complex than the simulation, and, on the other hand, these models are based on given structures. If the structure is not in good accordance with the reality, the model will be impossible to grasp the characteristics of the actual movement, or correctly determine the relationship between the external environment and its own movement. This is the biggest obstacle to robot’s mobile intelligence.

4.3.2. Case Two

In this case, the EKF, UKF, CKF, and PF were used to track the trajectory in Figure 7, in which the adaptive model was used. The tracking covariances of each estimation methods are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison on tracking covariance of EKF, UKF, CKF and PF with adaptive model.

It can be seen that the filters have similar performance. The estimated covariance of EKF is the largest, which shows the disadvantage of EKF when dealing with strong nonlinearity. UKF and CKF have the similar tracking covariance, the same conclusion has been gotten by other research works [84,85]: they both have higher accuracy than the EKF. A similar conclusion was reached in Ref. [86] for bearings-only tracking (BOT) problem. Pesonen and Piché [87] also compared a UKF and CKF using an extensive set of positioning benchmarks, including real and simulated data from GPS and mobile phone base stations, and resulting in conclusion that in tested scenarios no particular filter in this family is clearly superior. Therefore, although the CKF was developed later than the UKF, we find that it does not have the obvious advantages than UKF.

As to the PF, in this simulated system, it did not show superior performance because the Gaussian noise was used. In fact, for the practical system with non-Gaussian noise, PF can be much better than other methods based on accurate modeling of the noise, while the performance of PF depends heavily on the modeling methods in Section 4.1. It means that if we use the inaccurate model, the tracking performance will decrease greatly.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we have presented a survey of navigation and tracking for mobile intelligence of robot. The survey takes a relation-based organizational approach to reviewing the literature on robot navigation and tracking, as shown in Figure 1. By fusing different sensors, the navigation, such as location and SLAM, can be achieved with more accurate estimated trajectory and attitude. For the practical applications, however, due to the complexity of the surroundings, the perception of a moving target is disturbed by the complex environment-that is, the sensor measurement model becomes inaccurate. The inaccuracy of the model will significantly reduce the performance of the estimation method, which has led to very low mobile intelligence of robots in the real scenes, which has even been called “stupid” movement. Despite some progress in deep learning in recent years, several issues remain to be addressed in improving navigation in robotics system:

- As we have mentioned in Section 5, it is necessary to combine the estimation and AI methods. In essence, the estimation method is based on probability theory, while the AI method, especially the deep learning method, is based on statistical analysis. These methods have different theoretical foundations, and bringing them together requires in-depth research. These two methods are complementary. However, how to use deep learning methods to provide a more realistic model and how to use the estimation method to develop the prior knowledge of the deep neural network is an open field of study.

- Reinforcement learning has become a novel form, by which, for example, AlphaGo Zero has become its own teacher [146] to learning how to play go. The system starts off with a neural network that knows nothing about the game and then plays games against itself. Finally, the neural network is tuned and updated to predict moves, as well as the eventual winner of the games. The new player AlphaGo is obviously different from human chess players obviously. It may well be better than a human being because it is its own teacher and is not taught by a human being. Can we guess that a robot could have more intelligence than humans? How can we know if it will be able to move faster and be more flexible?

- End-to-end navigation with high intelligence should be executed on the hardware comprising the robot. If the deep learning method is used, current terminal hardware cannot achieve such a large amount of training. The current mechanisms are generally to train the network offline on high-performance hardware such as GPUs, and then online to give the model’s output. The estimation methods usually use a recursion solution form of the state equation; the calculation amount is small and can be executed on current terminal hardware. If combined with the AI method, controlling the total amount of calculating required by the entire system must be considered.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by NSFC under Grant No. 61673002, Beijing Natural Science Foundation No. 9162002 and the Key Science and Technology Project of Beijing Municipal Education Commission of China No. KZ201510011012.

Author Contributions

Xue-Bo Jin and Yu-Ting Bai conceived and designed the whole structure of this survey. Ting-Li Su and Jian-Lei Kong wrote the paper. Bei-Bei Miao and Chao Dou contributed materials, especially the application part.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The Details about Estimation Methods

Appendix A.1. EKF

The details of the Standard Kalman Filter and EKF are shown in Table A1.

Appendix A.2. UKF

Table A1.

The details of the Standard Kalman Filter and EKF.

Table A1.

The details of the Standard Kalman Filter and EKF.

| Different Parts of Filter | Standard Kalman Filter | EKF |

|---|---|---|

| System Model | ||

| Transformation | / | |

| Prediction of the State | ||

| Updaton of the State | ||

| Filter gain | ||

| Prediction of the Covariance | ||

| Updaton of the Covariance |

Table A2.

The details of UKF.

Table A2.

The details of UKF.

| Different Parts of Filter | UKF |

|---|---|

| System Model | |

| Prediction of the State | where and with |

| Updation of the State | |

| Filter gain | |

| Prediction of the Covariance | |

| Updation of the Covariance |

Table A3.

The details of CKF.

Table A3.

The details of CKF.

| Different Parts of Filter | CKF |

|---|---|

| System Model | |

| Prediction of the State | where and with |

| Updaton of the State | |

| Filter gain | |

| Prediction of the Covariance | |

| Updaton of the Covariance |

References

- Horn, B.K.; Schunck, B.G. Determining optical flow. Artif. Intell. 1981, 17, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.Z.; Atanasov, N.; Daniilidis, K. Event-based feature tracking with probabilistic data association. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 4465–4470. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, L.; Dai-Hong, J.; Rong, B.; Jin-Ping, S.; Wen-Jing, Z.; Chao, W. Moving object tracking method based on improved lucas-kanade sparse optical flow algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Wuxi, China, 14–17 September 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Leshed, G.; Velden, T.; Rieger, O.; Kot, B.; Sengers, P. In-car gps navigation: Engagement with and disengagement from the environment. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, C.; Kessler, C.; Wankerl, M.; Trommer, G. Dual IMU indoor navigation with particle filter based map-matching on a smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Zurich, Switzerland, 15–17 September 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolos, I.K.; Valavanis, K.P.; Tsourveloudis, N.C.; Kostaras, A.N. Evolutionary algorithm based offline/online path planner for UAV navigation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B 2003, 33, 898–912. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, S.A.; Bateman, S.S. Sensor measurements for Wi-Fi location with emphasis on time-of-arrival ranging. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2007, 6, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zàruba, G.V.; Huber, M.; Kamangar, F.; Chlamtac, I. Indoor location tracking using RSSI readings from a single Wi-Fi access point. Wirel. Netw. 2007, 13, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.C.; Gregorwich, W.; Capots, L.; Liccardo, D. Ultra-wideband for navigation and communications. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 10–17 March 2001; Volume 2, pp. 2–785. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.R.; Sul, S.K.; Park, M.H. Speed sensorless vector control of induction motor using extended Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1994, 30, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, A.M. Quaternion-based extended Kalman filter for determining orientation by inertial and magnetic sensing. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 53, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julier, S.J.; Uhlmann, J.K. Unscented filtering and nonlinear estimation. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, I.; Haykin, S. Cubature kalman filters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2009, 54, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.A. Estimating optimal tracking filter performance for manned maneuvering targets. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1970, AES-6, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jing, Z.; Wang, P. Maneuvering Target Tracking; National Defense Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jilkov, V.; Angelova, D.; Semerdjiev, T.A. Design and comparison of mode-set adaptive IMM algorithms for maneuvering target tracking. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1999, 35, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.B.; Du, J.J.; Jia, B. Maneuvering target tracking by adaptive statistics model. J. China Univ. Posts Telecommun. 2013, 20, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X. INS algorithm using quaternion model for low cost IMU. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2004, 46, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, F.M.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Kalman filter-based algorithm for IMU-camera calibration: Observability analysis and performance evaluation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistér, D.; Naroditsky, O.; Bergen, J. Visual odometry. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2004), Washington, DC, USA, 27 June–2 July 2004; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elfes, A. Using occupancy grids for mobile robot perception and navigation. Computer 1989, 22, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S. Learning metric-topological maps for indoor mobile robot navigation. Artif. Intell. 1998, 99, 21–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, G.N.; Kak, A.C. Vision for mobile robot navigation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, M.; Zhu, X.; Kalata, P. Sensor fusion for mobile robot navigation. Proc. IEEE 1997, 85, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambooij, M.; Fortuin, M.; Heynderickx, I.; IJsselsteijn, W. Visual discomfort and visual fatigue of stereoscopic displays: A review. J. Imaging Sci. Technol. 2009, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hwang, D.H. Vision/INS integrated navigation system for poor vision navigation environments. Sensors 2016, 16, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babel, L. Flight path planning for unmanned aerial vehicles with landmark-based visual navigation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2014, 62, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs, B.; McLauchlan, P.F.; Hartley, R.I.; Fitzgibbon, A.W. Bundle adjustment—A modern synthesis. In International Workshop on Vision Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 298–372. [Google Scholar]

- Badino, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Kanade, T. Visual odometry by multi-frame feature integration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2–8 December 2013; pp. 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif, J.P.; George, M.; Laverne, M.; Kelly, A.; Stentz, A. A new approach to vision-aided inertial navigation. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 4161–4168. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, P.; Wang, R.; Cremers, D. Online Photometric Calibration for Auto Exposure Video for Realtime Visual Odometry and SLAM. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1710.02081. [Google Scholar]

- Peretroukhin, V.; Clement, L.; Kelly, J. Reducing drift in visual odometry by inferring sun direction using a bayesian convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 2035–2042. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.; Golnaraghi, M. A quaternion-based orientation estimation algorithm using an inertial measurement unit. In Proceedings of the Position Location and Navigation Symposium, PLANS 2004, Monterey, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2004; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Mousa, A.M. GPS travelling wave fault locator systems: Investigation into the anomalous measurements related to lightning strikes. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1996, 11, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchli, B.; Sutton, F.; Beutel, J. GPS-equipped wireless sensor network node for high-accuracy positioning applications. In European Conference on Wireless Sensor Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Shen, S. CSI-based WiFi-inertial state estimation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI), Baden-Baden, Germany, 19–21 September 2016; pp. 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, A.; Tank, B.; Meghani, S.K.; Ahmed, S.; Tepe, K. Accurate UWB and IMU based indoor localization for autonomous robots. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 30th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Windsor, ON, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Su, Y.W.; Shen, C.C. A comparative study of wireless protocols: Bluetooth, UWB, ZigBee, and Wi-Fi. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, IECON 2007, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–8 November 2007; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Corna, A.; Fontana, L.; Nacci, A.; Sciuto, D. Occupancy detection via iBeacon on Android devices for smart building management. In Proceedings of the 2015 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition, EDA Consortium, Grenoble, France, 9–13 March 2015; pp. 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.Y.; Ho, T.W.; Fang, C.C.; Yen, Z.S.; Yang, B.J.; Lai, F. A mobile indoor positioning system based on iBeacon technology. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; pp. 4970–4973. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Cui, B.; Zhou, W.; Yokoi, S. A proposal of interaction system between visitor and collection in museum hall by iBeacon. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Cambridge, UK, 22–24 July 2015; pp. 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Koühne, M.; Sieck, J. Location-based services with iBeacon technology. In Proceedings of the 2014 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Modelling and Simulation (AIMS), Madrid, Spain, 18–20 November 2014; pp. 315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.B.; Dou, C.; Su, T.l.; Lian, X.f.; Shi, Y. Parallel irregular fusion estimation based on nonlinear filter for indoor RFID tracking system. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2016, 12, 1472930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, J. A comprehensive multi-factor analysis on RFID localization capability. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2011, 25, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Vinyals, O.; Friedland, G.; Bajcsy, R. Precise indoor localization using smart phones. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia. ACM, Firenze, Italy, 25–29 October 2010; pp. 787–790. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Shao, H.R. WiFi-based indoor positioning. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2015, 53, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, E.; Capitán, J.; Marrón, P.J. From Fast to Accurate Wireless Map Reconstruction for Human Positioning Systems. In Iberian Robotics Conference; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kotaru, M.; Joshi, K.; Bharadia, D.; Katti, S. SpotFi: Decimeter Level Localization Using WiFi. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2015, 45, 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Lv, C.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Ding, D. An innovative information fusion method with adaptive Kalman filter for integrated INS/GPS navigation of autonomous vehicles. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 100, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, H.V. Tightly-coupled INS/GPS integration with magnetic aid. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Control and Robotics Engineering (ICCRE), Bangkok, Thailand, 1–3 April 2017; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Alatise, M.B.; Hancke, G.P. Pose Estimation of a Mobile Robot Based on Fusion of IMU Data and Vision Data Using an Extended Kalman Filter. Sensors 2017, 17, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H. Monocular Vision-and IMU-Based System for Prosthesis Pose Estimation During Total Hip Replacement Surgery. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2017, 11, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyavej, V.; Kumkeaw, W.; Aorpimai, M. Indoor robot localization by RSSI/IMU sensor fusion. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Krabi, Thailand, 15–17 May 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Gu, J.; Milios, E.E.; Huynh, P. Navigation with IMU/GPS/digital compass with unscented Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference Mechatronics and Automation, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 29 July–1 August 2005; Volume 3, pp. 1497–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, B.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, Q. Indoor robot navigation by coupling IMU, UWB, and encode. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Conference on Software, Knowledge, Information Management & Applications (SKIMA), Chengdu, China, 15–17 December 2016; pp. 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Sun, B.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhuang, X. Data Fusion for Indoor Mobile Robot Positioning Based on Tightly Coupled INS/UWB. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 1079–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.R.J.; Granja, F.S.; Honorato, J.C.P.; Rosas, J.I.G. Accurate pedestrian indoor navigation by tightly coupling foot-mounted IMU and RFID measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.R.; Seco, F.; Zampella, F.; Prieto, J.C.; Guevara, J. Indoor localization of persons in aal scenarios using an inertial measurement unit (IMU) and the signal strength (SS) from RFID tags. In International Competition on Evaluating AAL Systems through Competitive Benchmarking; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, F.; Duflos, E.; Pomorski, D.; Vanheeghe, P. GPS/IMU data fusion using multisensor Kalman filtering: Introduction of contextual aspects. Inf. Fusion 2006, 7, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J.A.; White, E. Fusion Filter Algorithm Enhancements for a MEMS GPS/IMU; Crossbow Technology Inc.: Milpitas, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saadeddin, K.; Abdel-Hafez, M.F.; Jarrah, M.A. Estimating vehicle state by GPS/IMU fusion with vehicle dynamics. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2014, 74, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werries, A.; Dolan, J.M. Adaptive Kalman Filtering Methods for Low-Cost GPS/INS Localization for Autonomous Vehicles; Research Showcase CMU: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://http://repository.cmu.edu/robotics/ (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Zhao, Y. Applying Time-Differenced Carrier Phase in Nondifferential GPS/IMU Tightly Coupled Navigation Systems to Improve the Positioning Performance. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, L.; Bellone, M.; Svensson, L.; Wahde, M. LIDAR-based Driving Path Generation Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networks; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat, M.A.K.; Abdel-Hafez, M.F. Non-Linear Autoregressive Delay-Dependent INS/GPS Navigation System Using Neural Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanci, E.; Bostanci, B.; Kanwal, N.; Clark, A.F. Sensor fusion of camera, GPS and IMU using fuzzy adaptive multiple motion models. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Eckenhoff, K.; Leonard, J. Optimal-state-constraint EKF for visual-inertial navigation. In Robotics Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huo, L. A Vision/Inertia Integrated Positioning Method Using Position and Orientation Matching. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 6835456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; He, B.; Dong, X.; Dong, J. Monocular visual-IMU odometry using multi-channel image patch exemplars. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 11975–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascani, A.; Frontoni, E.; Mancini, A.; Zingaretti, P. Feature group matching for appearance-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS 2008, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 3933–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Audi, A.; Pierrot-Deseilligny, M.; Meynard, C.; Thom, C. Implementation of an IMU Aided Image Stacking Algorithm in a Digital Camera for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sensors 2017, 17, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneip, L.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R.Y. Robust real-time visual odometry with a single camera and an IMU. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2011; British Machine Vision Association: Durham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spaenlehauer, A.; Fremont, V.; Sekercioglu, Y.A.; Fantoni, I. A Loosely-Coupled Approach for Metric Scale Estimation in Monocular Vision-Inertial Systems; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, D. An algorithm for tracking multiple targets. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1979, 24, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, M.S. Kalman filtering. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany; London, UK, 2011; pp. 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Sinharay, A.; Pal, A.; Bhowmick, B. A kalman filter based approach to de-noise the stereo vision based pedestrian position estimation. In Proceedings of the 2011 UkSim 13th International Conference on Computer Modelling and Simulation (UKSim), Cambridge, UK, 30 March–1 April 2011; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ljung, L. Asymptotic behavior of the extended Kalman filter as a parameter estimator for linear systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1979, 24, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshiya, M.; Saito, E. Structural identification by extended Kalman filter. J. Eng. Mech. 1984, 110, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaouadi, R.; Mohan, N.; Norum, L. Design and implementation of an extended Kalman filter for the state estimation of a permanent magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1991, 6, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marins, J.L.; Yun, X.; Bachmann, E.R.; McGhee, R.B.; Zyda, M.J. An extended Kalman filter for quaternion-based orientation estimation using MARG sensors. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Maui, HI, USA, 29 October–3 November 2001; Volume 4, pp. 2003–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Baum, M. Extended Kalman filter for extended object tracking. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 March 2017; pp. 4386–4390. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, S.J. The scaled unscented transformation. In Proceedings of the 2002 American Control Conference, Anchorage, AK, USA, 8–10 May 2002; Volume 6, pp. 4555–4559. [Google Scholar]

- Hong-de, D.; Shao-wu, D.; Yuan-cai, C.; Guang-bin, W. Performance comparison of EKF/UKF/CKF for the tracking of ballistic target. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2012, 10, 1692–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Balaji, B. Comparison of the unscented and cubature Kalman filters for radar tracking applications. In Proceedings of the IET International Conference on Radar Systems, Glasgow, UK, 22–25 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jagan, B.O.L.; Rao, S.K.; Lakshmi, M.K. Concert Assessment of Unscented and Cubature Kalman Filters for Target Tracking. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2017, 9, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen, H.; Piché, R. Cubature-based Kalman filters for positioning. In Proceedings of the 2010 7th Workshop on Positioning Navigation and Communication (WPNC), Dresden, Germany, 11–12 March 2010; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Hu, B.; Li, A.; Qin, F. Transformed unscented Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunik, J.; Straka, O.; Simandl, M. Stochastic integration filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Clifford, P.; Fearnhead, P. Improved particle filter for nonlinear problems. IEE Proc.-Radar Sonar Navig. 1999, 146, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Merwe, R.; Doucet, A.; De Freitas, N.; Wan, E.A. The unscented particle filter. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14 (NIPS 2001), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3–8 December 2001; pp. 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Chopin, N. A sequential particle filter method for static models. Biometrika 2002, 89, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummiaro, K.; Koller-Meier, E.; Van Gool, L. An adaptive color-based particle filter. Image Vis. Comput. 2003, 21, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulampalam, M.S.; Maskell, S.; Gordon, N.; Clapp, T. A tutorial on particle filters for online nonlinear/non-Gaussian Bayesian tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qu, Y.; Xi, Z.; Bo, Y.; Liu, B. Efficient Particle Swarm Optimized Particle Filter Based Improved Multiple Model Tracking Algorithm. Comput. Intell. 2017, 33, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Minsky, M.L.; Rochester, N.; Shannon, C.E. A proposal for the dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence, 31 August 1955. AI Mag. 2006, 27, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, T. Machines that think. Sci. Am. 1933, 148, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. The Perceptron a Perceiving and Recognizing Automaton; Tech. Rep.; Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1957; pp. 85–460. [Google Scholar]

- Crevier, D. AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CireşAn, D.; Meier, U.; Masci, J.; Schmidhuber, J. Multi-column deep neural network for traffic sign classification. Neural Netw. 2012, 32, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Seeliger, K.; Fritsche, M.; Güçlü, U.; Schoenmakers, S.; Schoffelen, J.M.; Bosch, S.; van Gerven, M. Convolutional neural network-based encoding and decoding of visual object recognition in space and time. NeuroImage 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Meng, F.; Liu, H. 3D action recognition using multi-temporal skeleton visualization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Hong Kong, China, 10–14 July 2017; pp. 623–626. [Google Scholar]

- Polvara, R.; Sharma, S.; Wan, J.; Manning, A.; Sutton, R. Obstacle Avoidance Approaches for Autonomous Navigation of Unmanned Surface Vehicles. J. Navig. 2018, 71, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Konomis, D.; Neubig, G.; Xie, P.; Cheng, C.; Xing, E. Convolutional Neural Networks for Medical Diagnosis from Admission Notes; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network in Network; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. Enet: A Deep Neural Network Architecture for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A.A. Inception-v4, Inception-Resnet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning; AAAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 4, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Weinberger, K.Q.; van der Maaten, L. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Hawaii Convention Center, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Quebec, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. Shufflenet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Dollár, P.; He, K.; Darrell, T.; Girshick, R. Learning to Segment Every Thing; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, Y.; Khot, T.; Summers-Stay, D.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D. Making the V in VQA Matter: Elevating the Role of Image Understanding in Visual Question Answering; CVPR: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017; Volume 1, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutskever, I. Training Recurrent Neural Networks; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pascanu, R.; Mikolov, T.; Bengio, Y. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; pp. 1310–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Meng, H.; Xu, M.; Cai, L. Question detection from acoustic features using recurrent neural network with gated recurrent unit. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Shanghai, China, 20–25 March 2016; pp. 6125–6129. [Google Scholar]

- Gulcehre, C.; Chandar, S.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Dynamic Neural Turing Machine with Soft and Hard Addressing Schemes; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; The MIT Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Antol, S.; Agrawal, A.; Lu, J.; Mitchell, M.; Batra, D.; Lawrence Zitnick, C.; Parikh, D. Vqa: Visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Boston, MA, USA, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2425–2433. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Agrawal, H.; Zitnick, L.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Human attention in visual question answering: Do humans and deep networks look at the same regions? Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2017, 163, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, F.J.; Roggen, D. Deep convolutional and lstm recurrent neural networks for multimodal wearable activity recognition. Sensors 2016, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiffer, C.; Raghavendra, R.; Benson, T.; Srivatsa, M. DarNet: A Deep Learning Solution for Distracted Driving Detection. In Proceedings of the Middleware Industry 2017, Industrial Track of the 18th International Middleware Conference, Las. Vegas, NV, USA, 11–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Yan, B.; Wood, K. InnoGPS for Data-Driven Exploration of Design Opportunities and Directions: The Case of Google Driverless Car Project. J. Mech. Des. 2017, 139, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The KITTI dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Hu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Abdelzaher, T. Deepsense: A unified deep learning framework for time-series mobile sensing data processing. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gaudiot, J.L. CAAD: Computer Architecture for Autonomous Driving; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sucar, E.; Hayet, J.B. Bayesian Scale Estimation for Monocular SLAM Based on Generic Object Detection for Correcting Scale Drift; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noureldin, A.; El-Shafie, A.; Bayoumi, M. GPS/INS integration utilizing dynamic neural networks for vehicular navigation. Inf. Fusion 2011, 12, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezenac, E.d.; Pajot, A.; Patrick, G. Deep Learning for Physical Processes: Incorporating Prior Scientific Knowledge; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Fritz, M.; Schiele, B. Long-Term On-Board Prediction of People in Traffic Scenes under Uncertainty; Cornell University arXiv Institution: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).