1. Introduction

As a very important heat transfer medium, ethylene glycol/water mixtures are widely used in many different kinds of industrial equipment including car radiators, air conditioning systems, and liquid cooled computers [

1]. In the past few decades, with the rapid development of various compact heat exchange components, the conventional ethylene glycol/water mixtures have been unable to effectively meet the ever-increasing demand for cooling due to their lower thermal conductivity. Therefore, how to develop enhanced heat transfer technology has become a very important problem in the fields of thermal engineering [

2].

Nanofluids, a special liquid-solid mixture containing a base fluid and nanoparticles (usually less than 100 nm), have drawn increasing attention recently because of their advantages in thermal conductivity and stability [

3]. Many investigations indicated that nanofluids could be an effective technology to improve the heat transfer performance of systems using ethylene glycol/water mixtures as coolant [

4]. For example, the experimental results of Vajjha and Das [

5] showed that at the temperature of 299 K, the thermal conductivities of the 60:40 (by weight ratio) ethylene glycol/water mixture could be increased by about 12.3% by adding ZnO nanoparticles (29 nm) with a volume fraction of 2%. Sundar et al. [

6] experimentally investigated the effects of Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles (13 nm) on three different kinds of ethylene glycol/water mixtures with weight ratios of 20:80, 40:60, and 60:40. They found that at the temperature of 60 °C and the nanoparticle volume fraction of 2%, the thermal conductivity enhancements of the above three ethylene glycol/water mixtures were 46%, 42%, and 33%, respectively.

Thermo-physical parameters are very important factors that affect the heat and mass transfer performance of nanofluids [

7,

8,

9]. Due to the fact that viscosity can significantly affect the flow internal resistance, inlet Reynolds number, and pressure drop, many experimental investigations have been carried out regarding the viscosity of different nanofluids. As reported by Azmi et al. [

10], the viscosity of the 40:60 (by volume ratio) ethylene glycol/water mixture could be increased obviously by dispersing TiO

2 nanoparticles. For example, the viscosity enhancement was about 12% when the nanoparticle volume fraction changed from 0.5% to 1.5%. Sundar et al. [

11] investigated the viscosity variations of Fe

3O

4-ethylene glycol/water nanofluids with different nanoparticle fractions and working temperatures. Their experimental results indicated that the viscosity of ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids could be increased by increasing the nanoparticle volume fraction and decreasing temperature. At a nanoparticle volume fraction of 1%, the viscosity of the base fluid could be enhanced by 2.9 times. Chen et al. [

12], Jamshidi et al. [

13], Kulkarni et al. [

14], Rudyak et al. [

15], Namburu et al. [

16], Lim et al. [

17], Chiam et al. [

18], and Li et al. [

19] respectively measured the viscosity of various ethylene glycol/water mixture based nanofluids with the effects of different factors. According to their experimental results, it was found that a suspension of nanoparticles could enhance the viscosity of the base fluid in different degrees. Additionally, temperature, base fluid, and nanoparticle properties including volume fraction, size, type, and shape were the important factors affecting the enhancement of nanofluids’ viscosity.

For the basis of the experimental research, the modeling and prediction of viscosity is also very important for understanding the rheological behavior of nanofluids. Murshed and Estellé [

20] reviewed the latest developments of viscosity models for nanofluids. Their analysis indicated that although many theoretical models and empirical correlations have been developed for nanofluid viscosity, only a few of them were used for ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids. Additionally, since the effects of different factors on nanofluid viscosity were usually coupled and uncertain, it was still very difficult to accurately describe the viscosity characteristics of different nanofluids in a wide range of nanoparticle volume fractions, sizes, temperatures, etc. Therefore, how to develop an effective solution for the viscosity prediction of nanofluids is a hot topic in the field of nanofluids.

Artificial neural networks (ANN), a black box data analysis approach, has a strong nonlinear mapping ability to establish the relationship between input and output variables without considering the detailed physical process. Due to the advantages of ANNs such as high speed, simplicity, and large capacity, various ANNs were put forward to solve the modeling and prediction problems of nanofluid viscosity [

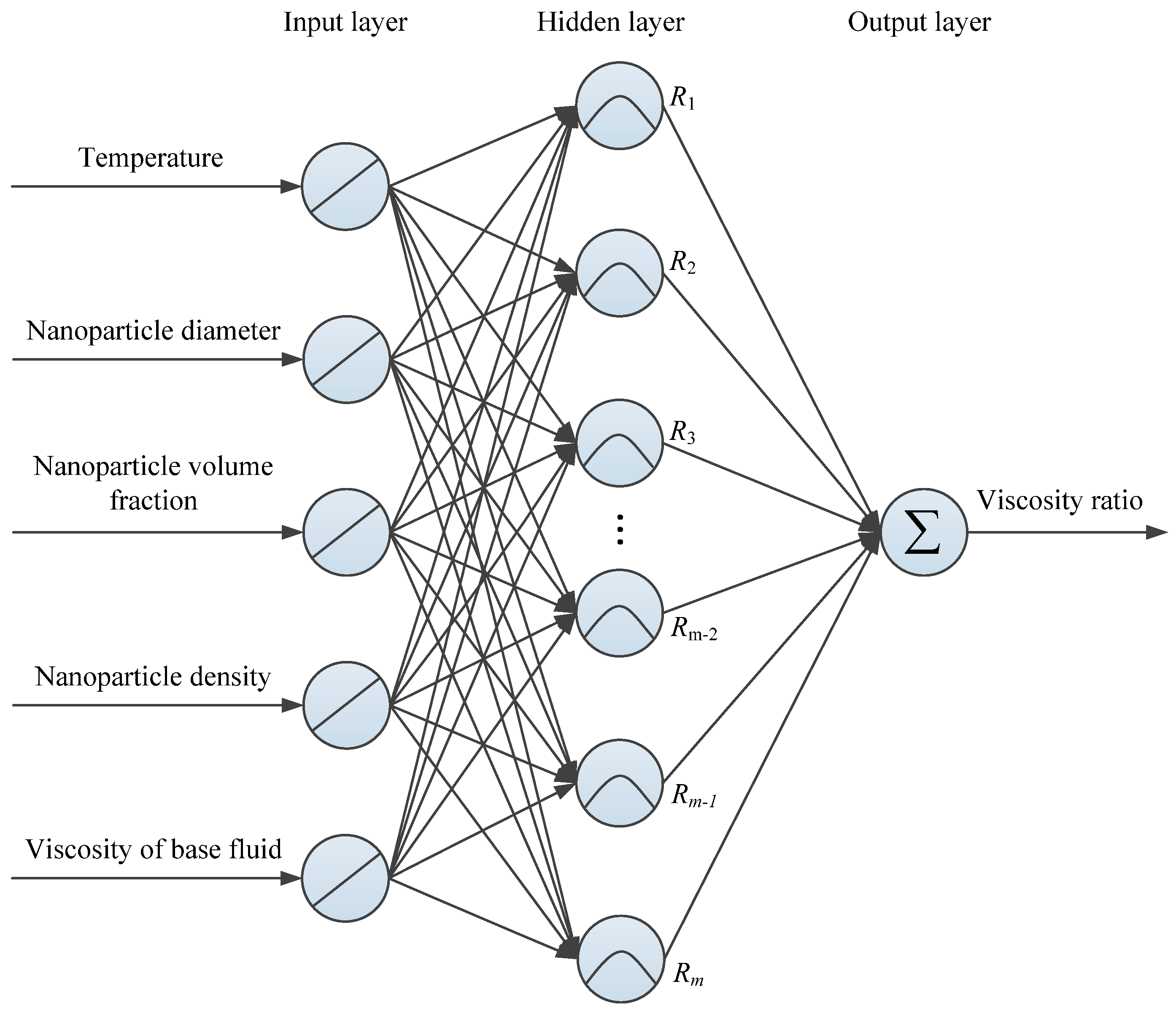

21]. Selecting five variables (temperature, nanoparticle volume fraction, nanoparticle size, viscosity of the base fluid, and relative density of the base fluid) and nanoparticles as the input, Yousefi et al. [

22] developed a diffusional neural network (DNN) to predict the viscosity of six different types of nanofluids. As reported in their analysis, DNN could be used for predicting the viscosity of nanofluids with satisfactory accuracy. On this basic, Mehrabi et al. [

23] analyzed the application of a Fuzzy C-Means-based Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (FCM-ANFIS) for the viscosity prediction of various water based nanofluids. They found that the FCM-ANFIS predicted values agreed well with the experimental data. Attracted by the better nonlinear mapping and recognition abilities of ANN, Zhao et al. [

24,

25] investigated the feasibility of RBF neural networks for predicting the viscosity of two water based nanofluids containing Al

2O

3 and CuO nanoparticles. Their results demonstrated that ANN was an effective tool in comparison with the traditional model-based approach for describing the enhancement behavior of nanofluid viscosity. They indicated that the addition of temperature as an input variable could improve the prediction performance of the RBF neural network.

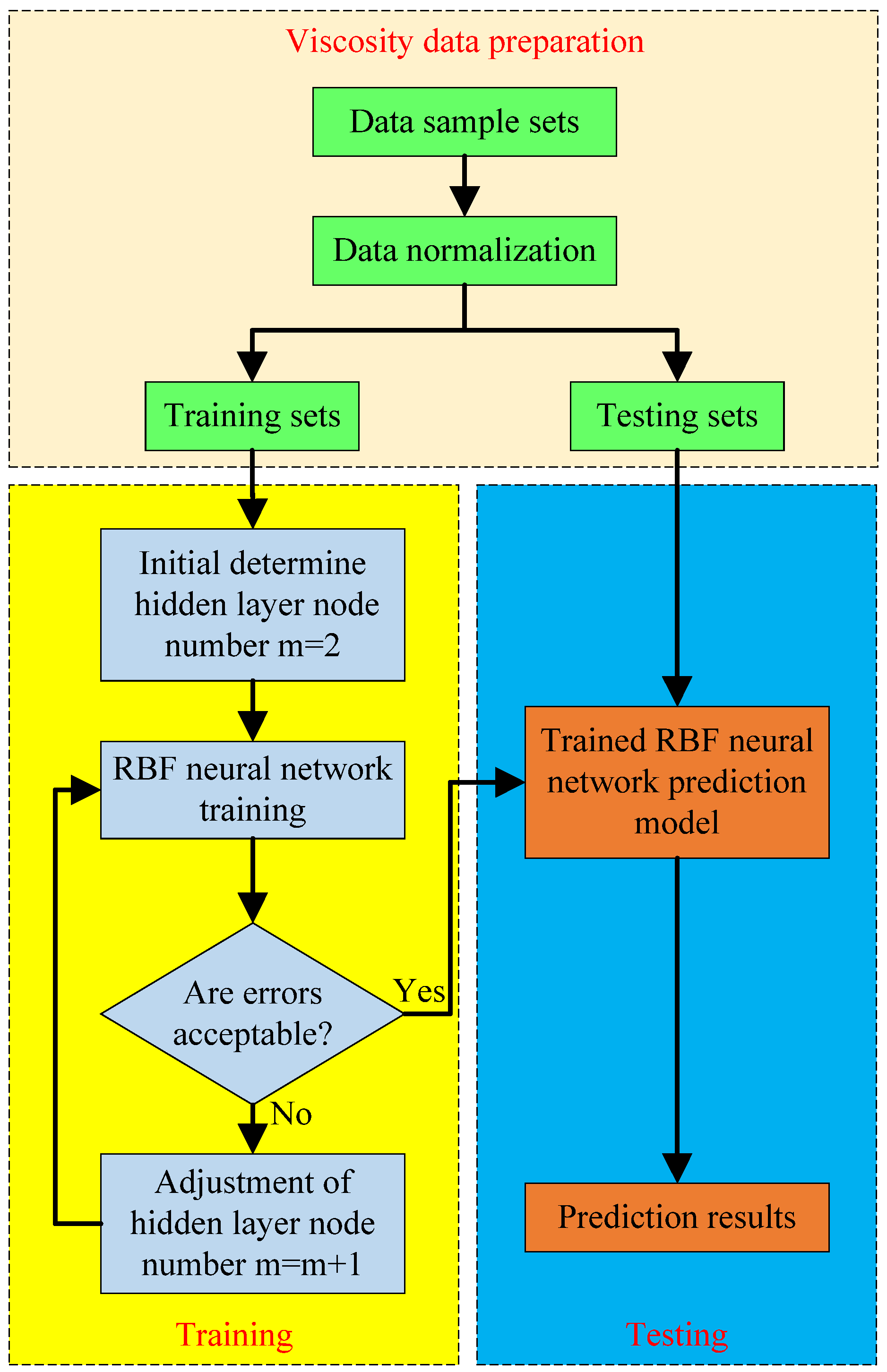

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are few publications that study the modeling and prediction of different ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids using ANN. Considering the advantages of RBF neural networks that are easier to design, and have faster training speed, higher training accuracy, stronger generalization ability, and stronger tolerance for input noise [

26], this paper selects a RBF neural network as a competitive method for predicting the viscosity characteristics of different ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids with different influence factors. Firstly, the basis theory and modeling process of the RBF neural network are introduced briefly. On this basis, the available measurements from various published studies are obtained to establish the data sample sets and train the RBF neural network for determining the network configuration. Finally, the RBF neural networks’ predicted results are compared with the experimental data to evaluate the prediction performance of the proposed model.

2. Basic Theory of a RBF Neural Network

Benefiting from the inspiration of the human brain’s structure and activity mechanism, many different artificial neural networks have been developed for different purposes including classification and regression. In the fields of curve-fitting and nonlinear predictive modeling, the RBF neural network proposed by Broomhead and Lowe [

27] can exhibit a good ability because of its high accuracy and stability [

28].

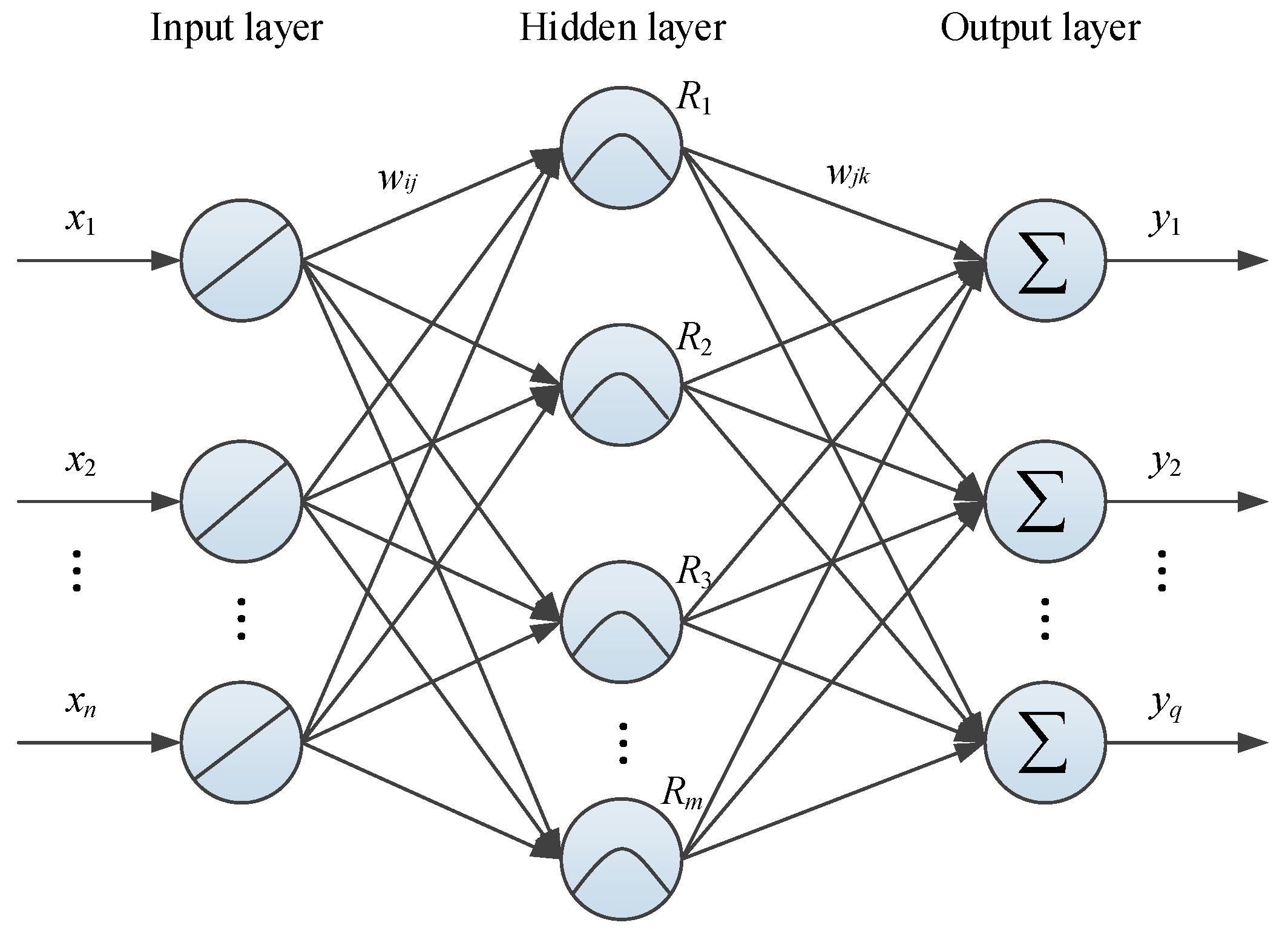

Figure 1 presents the basic structure of a typical three-layer RBF neural network. The input and output layers respectively correspond to the dendrite and synapse of biological neurons, which are used to mathematically describe the modeling object. The hidden layer, similar to the function of the cyton, plays a role of intermediation to process the input-output information and deliver it to the output layer. The connections between different layers are established through a series of artificial neurons and weights.

Theoretically, the modeling process of the RBF neural network is to solve the mapping from

to

(

) in Euclidean space. Assuming that the input vector of the RBF neural network is

, the response of the

th neuron in the output layer (

) can be obtained by using the following linear weighting function [

29].

where

is the connection weight between the

th hidden layer neuron and the

th output layer neuron.

and

q are the numbers of neurons in the corresponding layer, respectively.

Different from many other ANNs, the response of the RBF neural network’s

th hidden layer neuron is usually determined by the RBF. When it selects a Gaussian function, the corresponding

can be defined as,

where

is the Euclidean distance between the input vector

and the

th neuron center

.

is the width of the

th neuron.

Analyzing Equations (1) and (2), it can be easily found that the key of RBF neural network training is how to determine

,

, and

. In the past few decades, different unsupervised and supervised algorithms have been developed to solve this problem [

30]. In this study, the network parameters are updated by using an orthogonal least squares (OLS) approach, of which the minimizing function is shown in Equation (3). More detailed information about OLS can be found in [

31].

where

and

are the network output and desired output of the

th output layer node, respectively.

4. Results and Discussion

For the RBF neural network, the Spread is usually a very important factor influencing the training process.

Figure 4 shows the relationships of the mean square error (MSE) and the number of hidden layer neurons with different Spreads. Analyzing the results reported in

Figure 4, it is found that for the same converged target, the neuron numbers in the hidden layer need to be increased obviously with the decrease of the Spread. When the Spread varies from 1 to 0.1, the corresponding neuron configuration of the RBF neural network are 5-38-1, 5-40-1, 5-56-1, 5-67-1, and 5-105-1, respectively. With the decrease of the Spread, the CPU time for computing the RBF neural network will also increase. At a Spread of 1, 0.5, 0.3, 0.2, and 0.1, the corresponding CPU times are 6.318, 6.396, 8.798, 10.827, and 15.772 s, respectively. In addition,

Table 2 lists the values of four evaluation criteria for predicting the viscosity ratio of ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids by using the RBF neural network with different Spreads. It can be seen from

Table 2 that although all

are within the acceptable level of 0.99, the prediction performance of the RBF neural network is still affected by the value of the Spread, especially for the testing samples. Based on the comprehensive considerations of modeling complexity, prediction accuracy, and CPU time, the RBF neural network with the neuron configuration of 5-56-1 and Spread of 0.3 is used in this study. The related weights and biases of the 5-56-1 RBF neural network can be found in

Table 3.

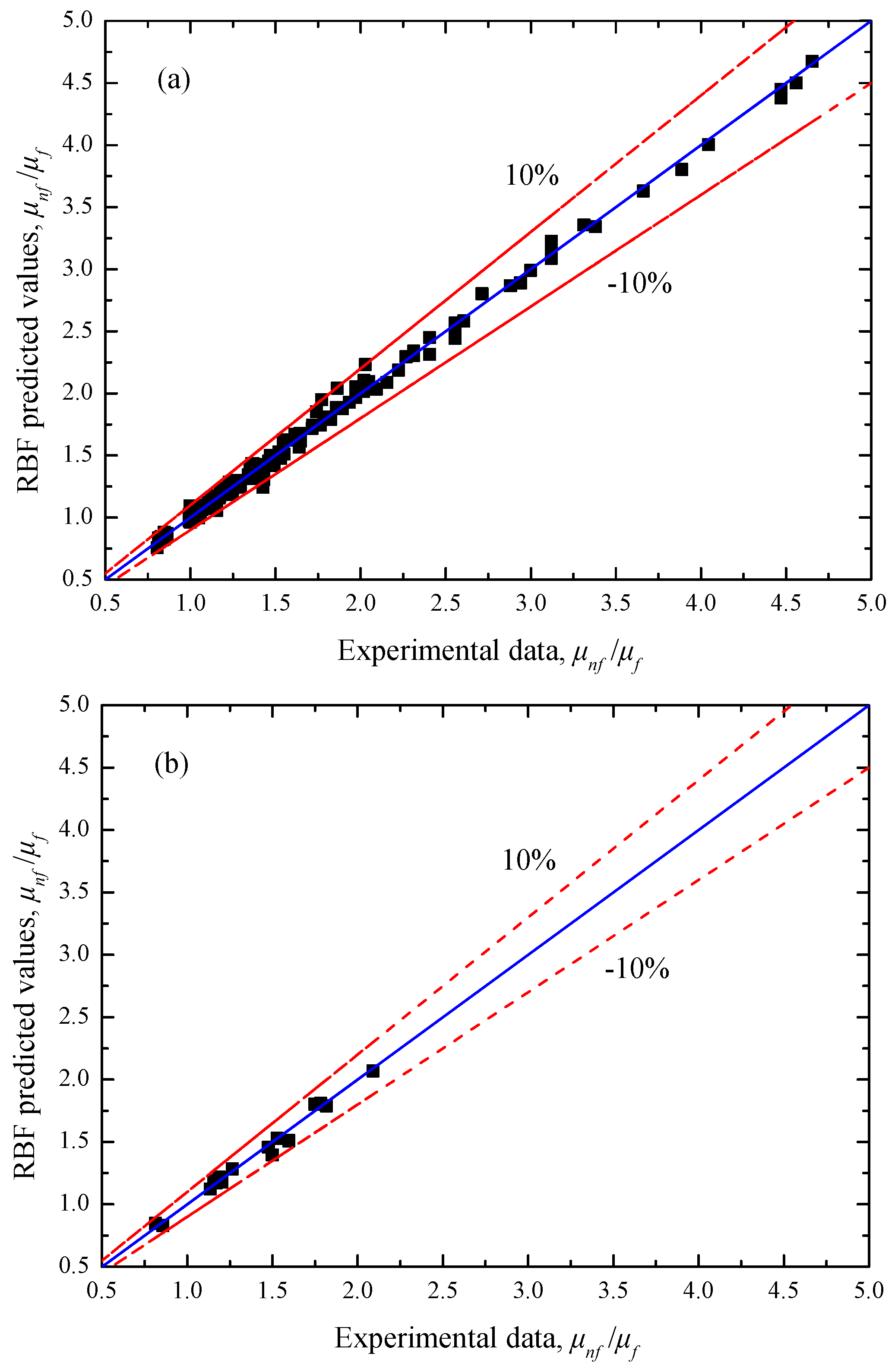

Figure 5 compares the predicted viscosity ratio of the RBF neural network and the experimental data involving the training and testing samples. It can be seen that all the prediction errors of the RBF neural network are within the ±10% error bands. As shown in

Table 2, the values of the four evaluation criteria are

RMSE = 0.04630,

MAPE = 2.09967%,

SSE = 0.42454, and

R2 = 0.99927 for the training samples, and

RMSE = 0.04443,

MAPE = 2.43228%,

SSE = 0.03553, and

R2 = 0.99904 for the testing samples, which preliminarily indicates that the RBF neural network has a good ability to predict the viscosity ratio of ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids.

To further evaluate the prediction performance of the RBF neural network for nanofluid viscosity, the following typical viscosity models which consider the effects of nanoparticle Brownian motion and aggregation are selected for analysis.

Chen model [

33]:

where

rp and

ra are the radius of nanoparticle and nanoparticle aggregation, respectively.

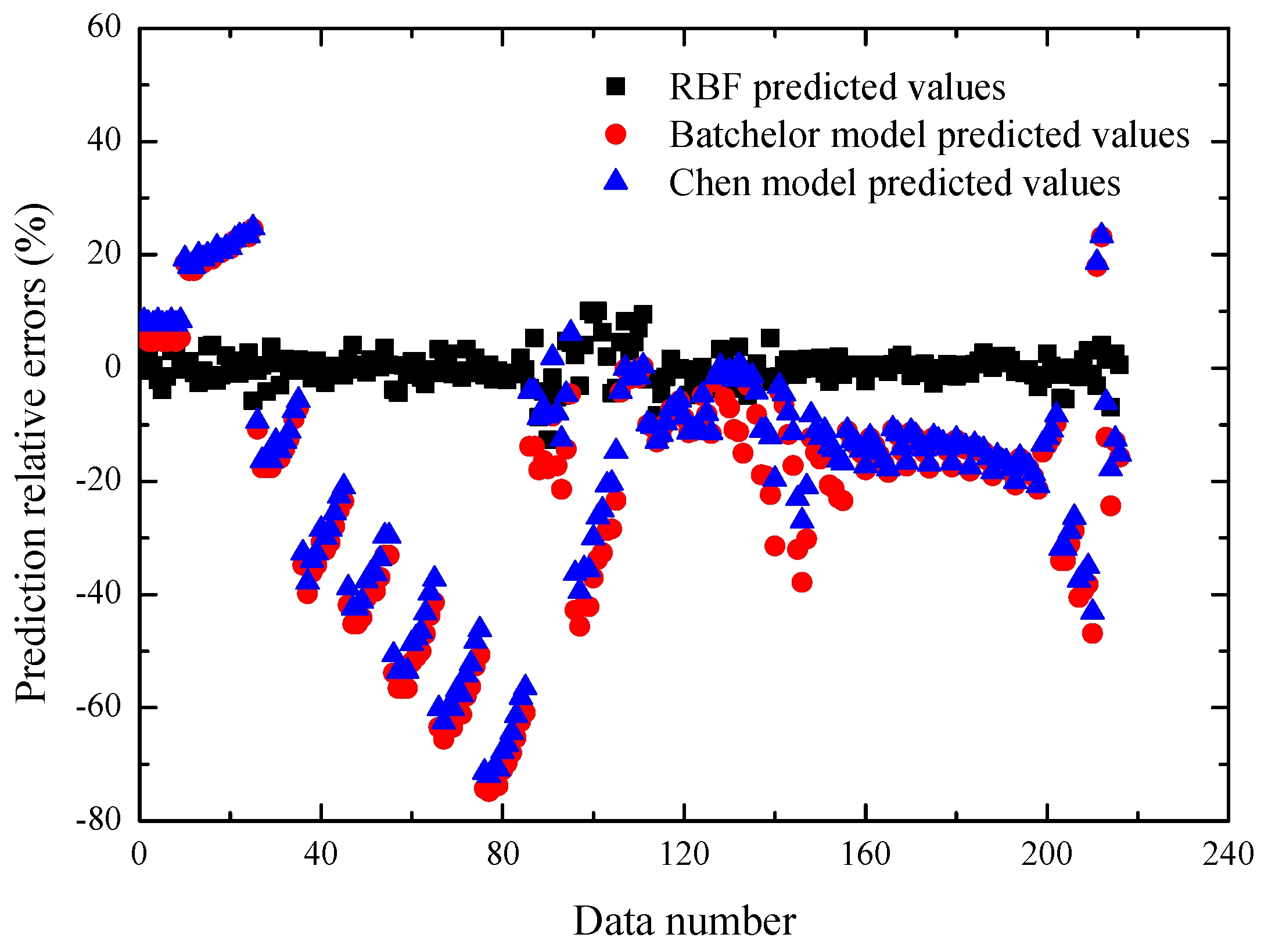

Figure 6 and

Table 4 respectively compare the prediction performances of the different models for the total viscosity data. It is easily seen that the RBF neural network has a better prediction accuracy than the above two typical models. The main reason is that the Batchelor model and Chen model cannot fully quantitatively describe the relationship between the nanofluid viscosity ratio and the various factors including the nanoparticle properties, temperature, and base fluid.

Moreover,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 respectively present the comparisons between the predicted viscosity ratio of the RBF neural network and the corresponding experimental data of Chen et al. [

12], Jamshidi et al. [

13], and Namburu et al. [

16]. It can be seen that there is good agreement between the RBF predicted and the experimental viscosity ratio of the different ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids. At the temperature range of 20–40 °C, the maximum and minimum prediction errors of the RBF neural network are respectively 5.788% and 0.434% for the experimental data of Chen et al. [

12]. For the viscosity ratio of the SiO

2-ethylene glycol/water (50:50 by volume ratio) nanofluid provided by Jamshidi et al. [

13], the RBF neural network can accurately predict the viscosity ratio with an average error of 1.772% at the nanoparticle volume fraction of 0.1%. Moreover, the comparisons shown in

Table 7 further illustrate that the developed RBF neural network has high accuracy (average error: 2.097%) for predicting the viscosity ratio of CuO-ethylene glycol/water (60:40 by weight ratio) nanofluids.

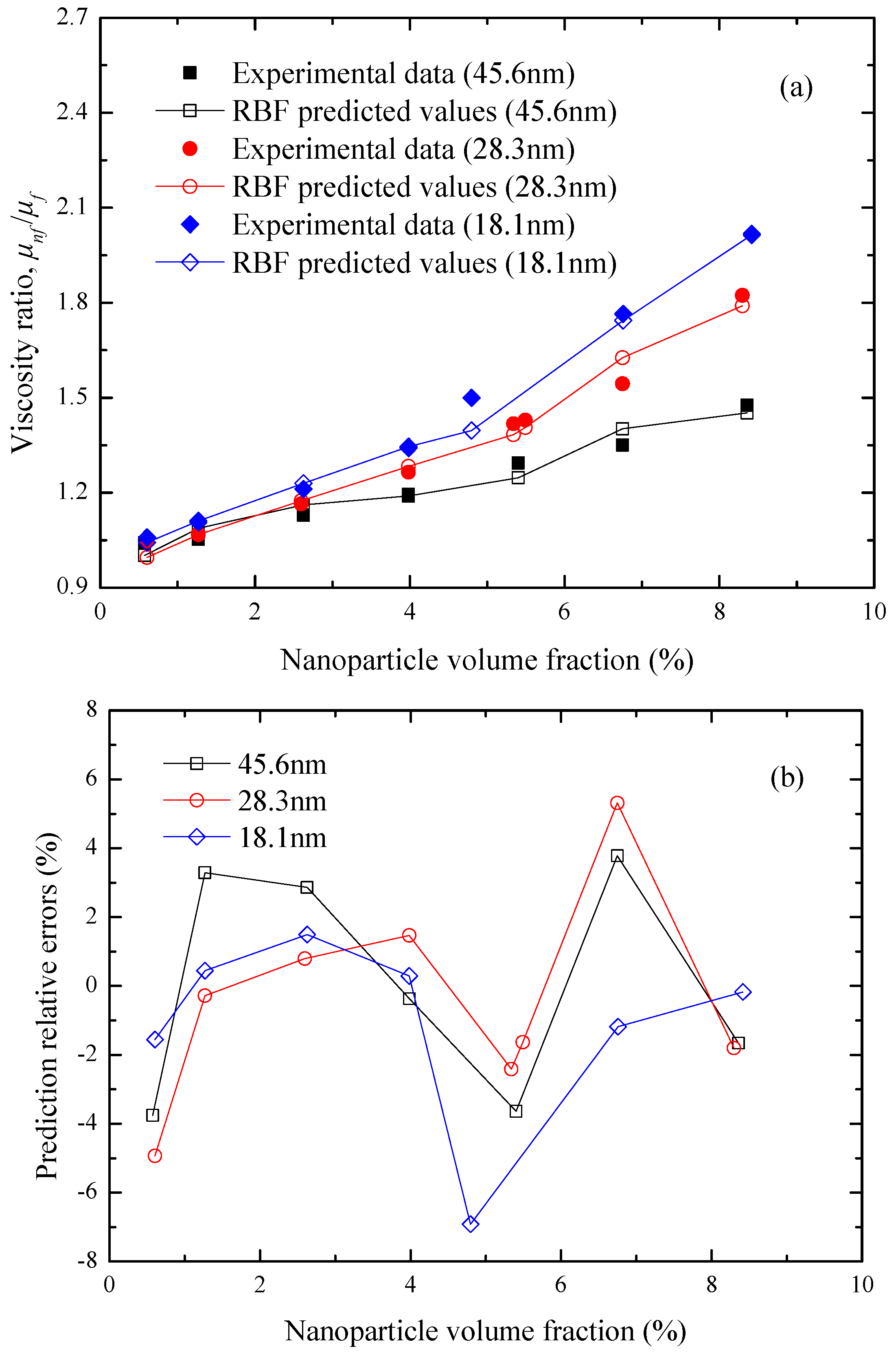

Figure 7 compares the experimental viscosity ratio of Rudyak et al. [

15] with the predicted values of the RBF neural network for the SiO

2-ethylene glycol nanofluids at

T = 25 °C as a function of the nanoparticle volume fraction and diameter. It can be found from

Figure 7a that the RBF predicted viscosity ratio of nanofluids are obviously enhanced with the increase of the SiO

2 nanoparticle volume fraction and the decrease of the nanoparticle size, which are consistent with the experimental results. All the prediction relative errors are within ±8%, as shown in

Figure 7b. On this basis,

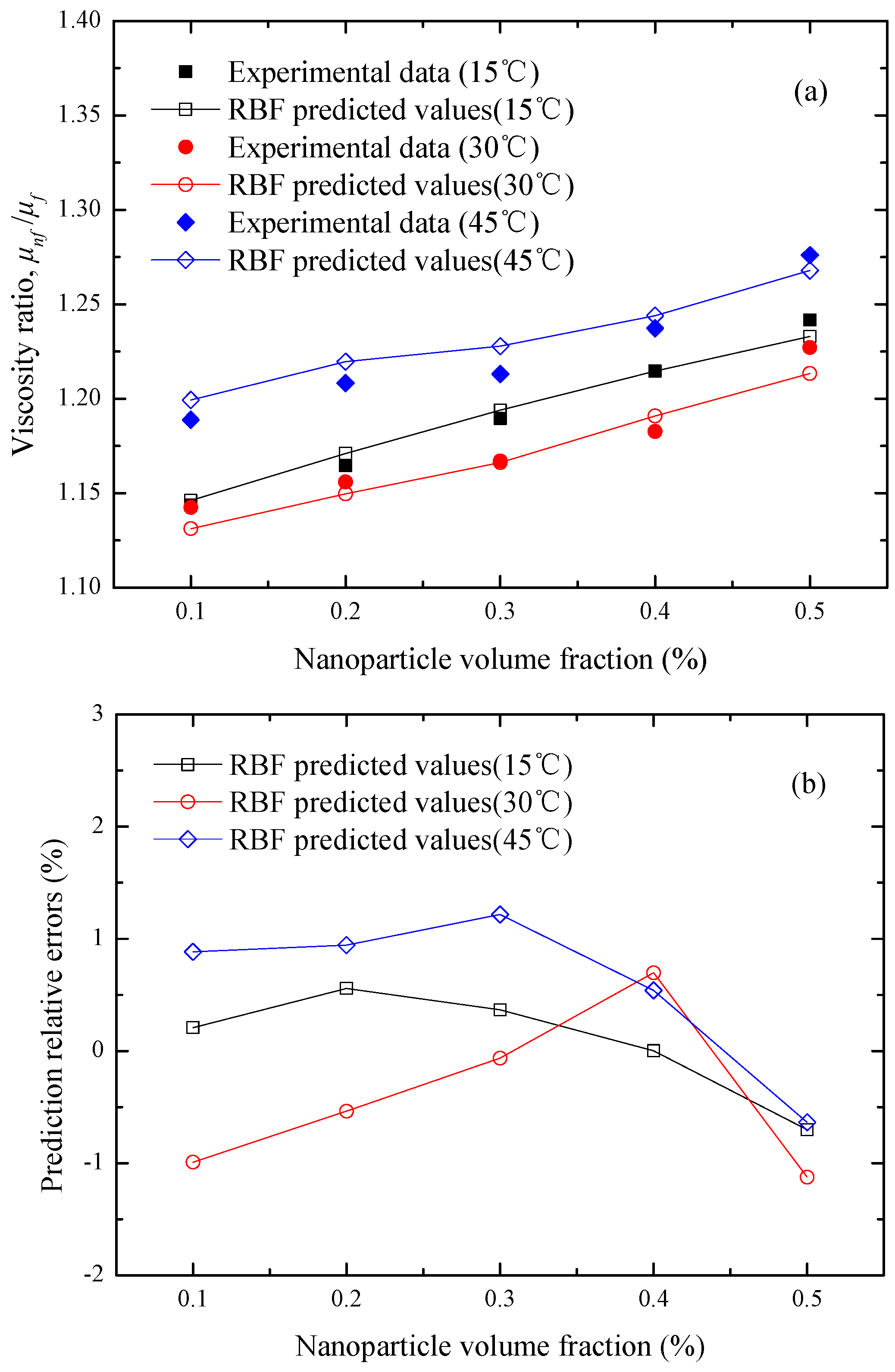

Figure 8 illustrates the comparisons between the RBF predicted values and the corresponding experimental data of Li et al. [

19]. The results indicate that the RBF neural network developed in this study can be applied successfully for predicting the effects of the nanoparticle volume fraction and temperature on the viscosity ratio of SiC-ethylene glycol/water (40:60 by weight ratio) nanofluids with a satisfactory accuracy. In addition, a similar analysis is performed for the CuO-ethylene glycol/water (60:40 by weight ratio) nanofluids as a function of temperature, which is presented in

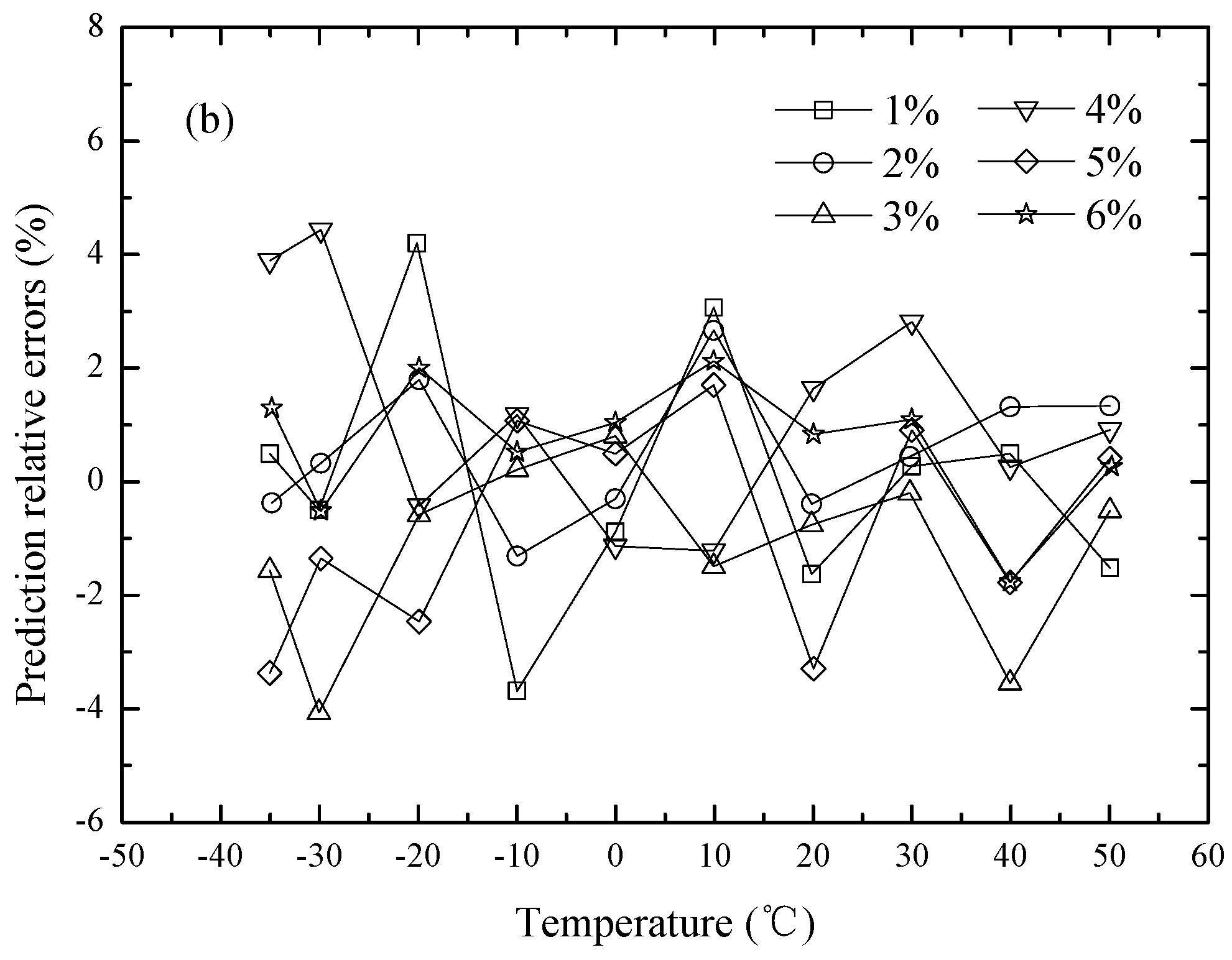

Figure 9. It is demonstrated that the viscosity ratio characteristics of the above nanofluids are effectively predicted by the RBF neural network in a wide range of nanoparticle volume fractions (from 1% to 6%) and temperatures (from −35 to 50 °C). The maximum prediction relative errors are only 4.2%. All the above analyses further demonstrate that the RBF neural network is one of the potential tools to quantitatively establish nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs.

Table 8 shows the prediction performance of the RBF neural network using different viscosity data sets. It is worth noting that the data sets are selected randomly. From

Table 8, we found that the size of the data set can affect the modeling and prediction of the RBF neural network significantly. With the decrease of the data set size, the prediction accuracy will decrease. This may mean that to accurately predict the viscosity of ethylene glycol/water based nanofluids using the RBF neural network, a large enough data set is necessary.