Exploratory Approach Using Laser-Induced Autofluorescence for Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer Diagnosis—Three Case Reports

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Protocol of Tissue Sampling

2.2. Laser-Induced Autofluorescence Spectroscopy

2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Laser-Induced Autofluorescence Spectroscopy

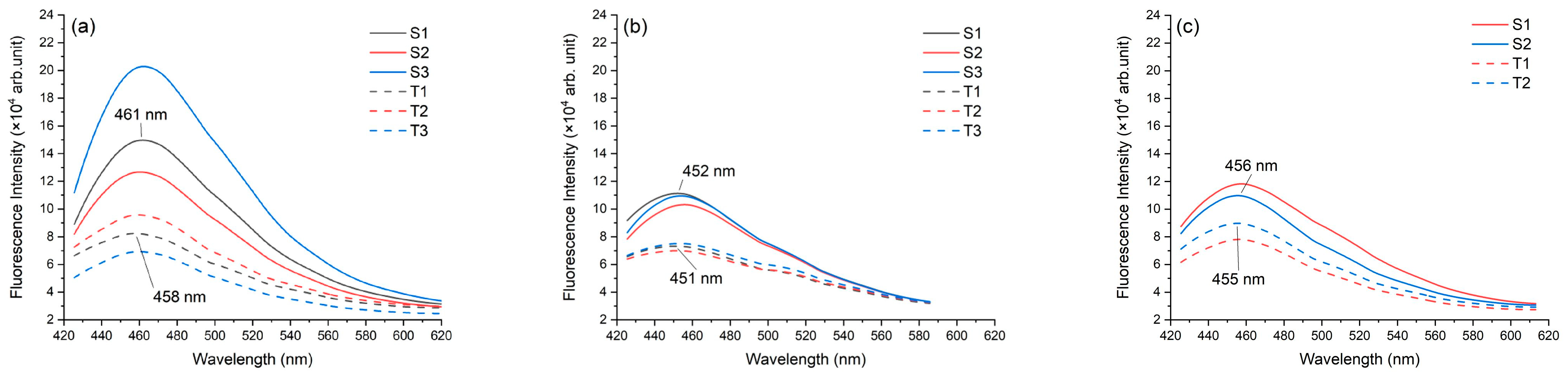

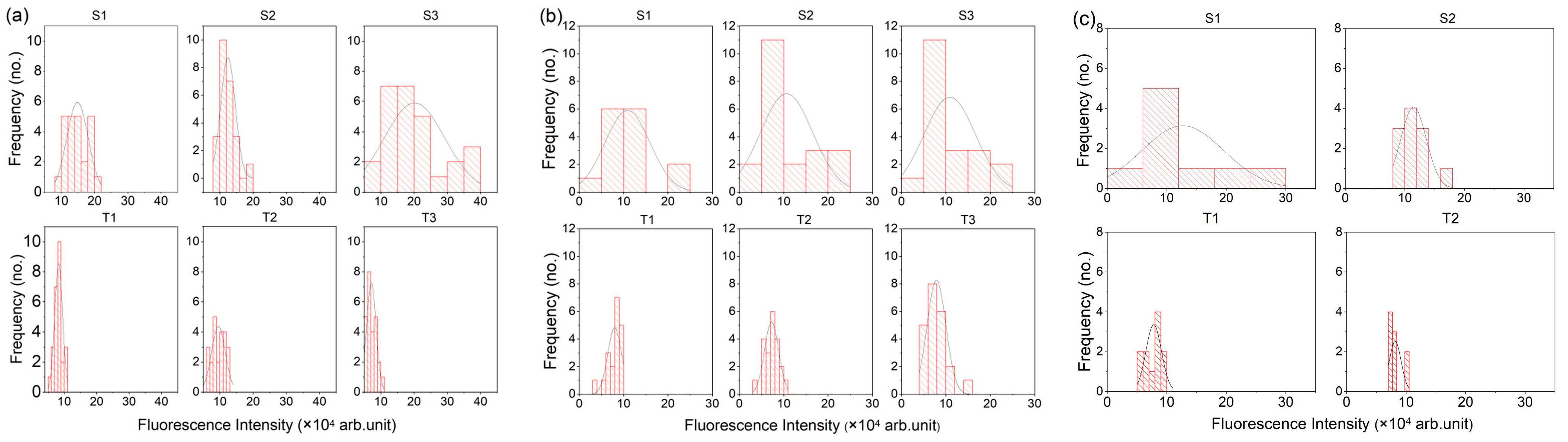

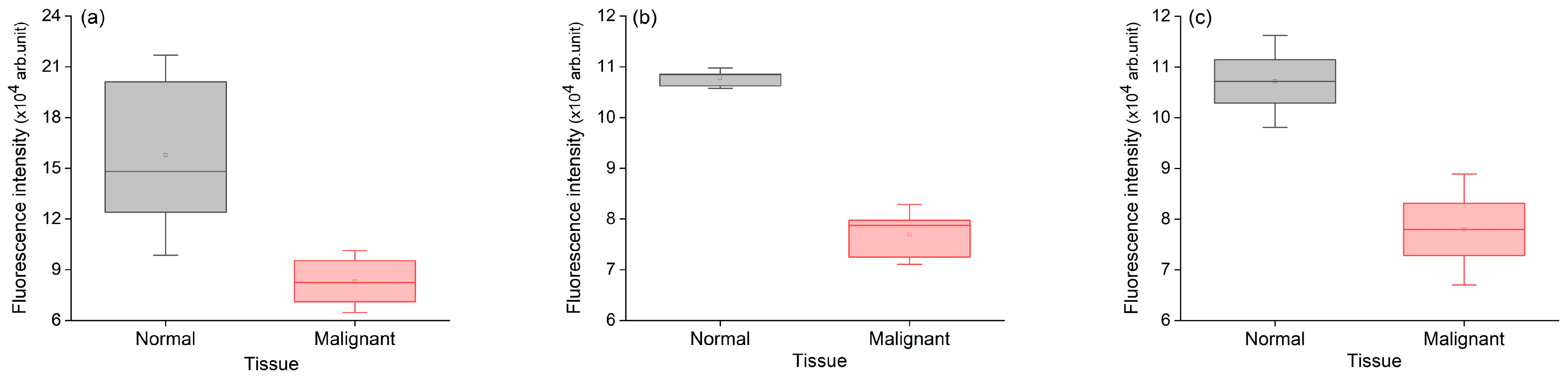

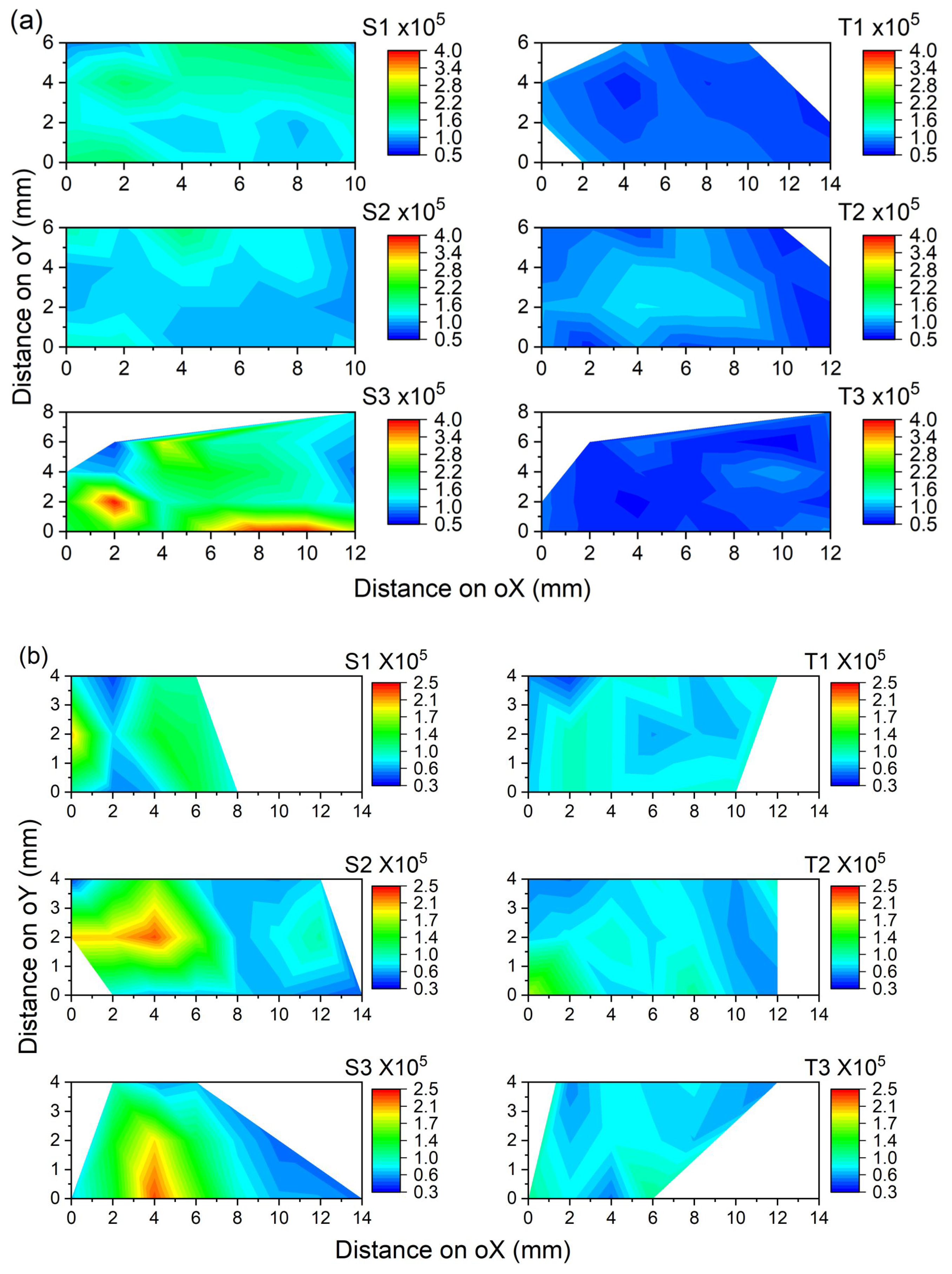

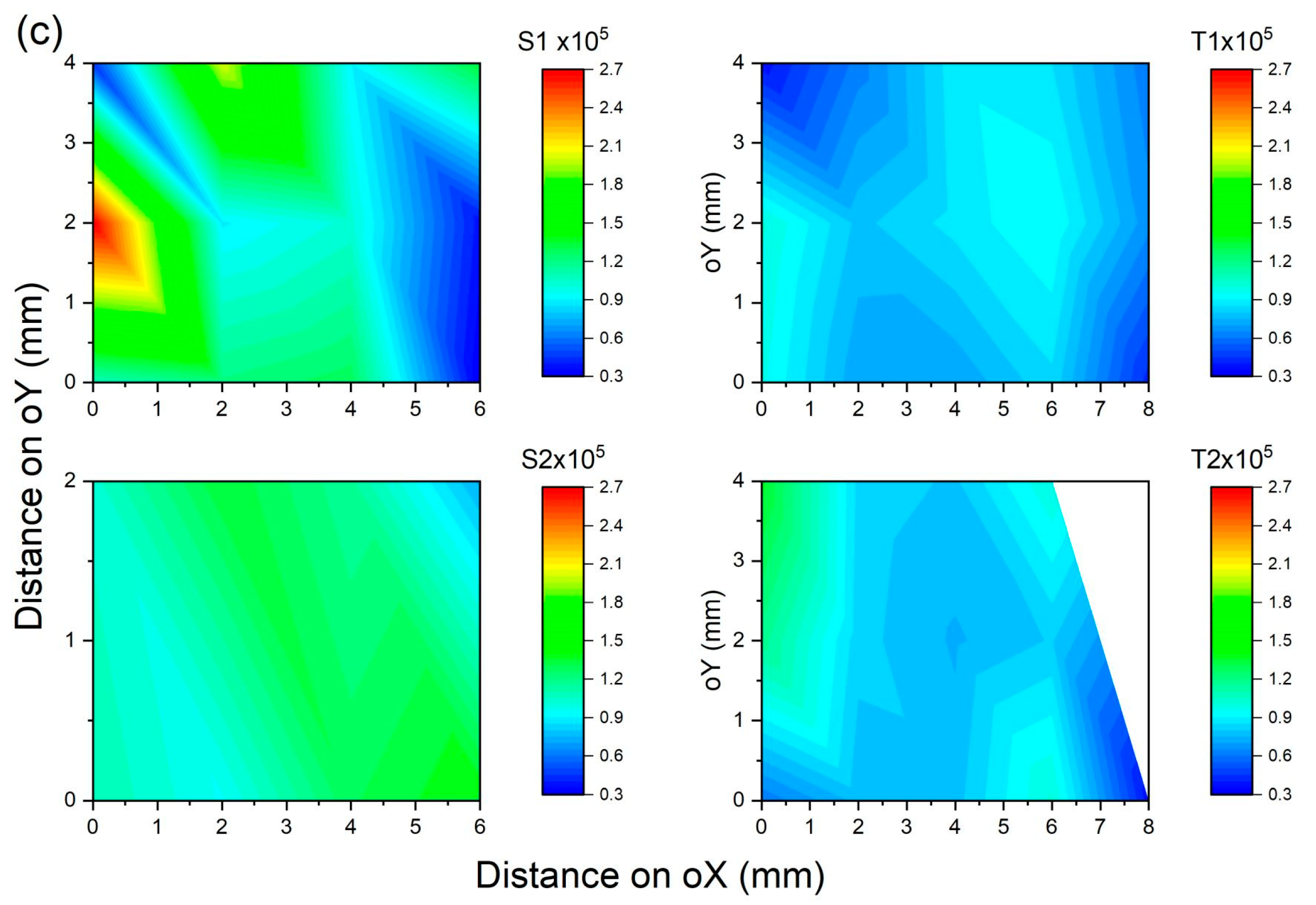

3.1.1. Fluorescence Intensity

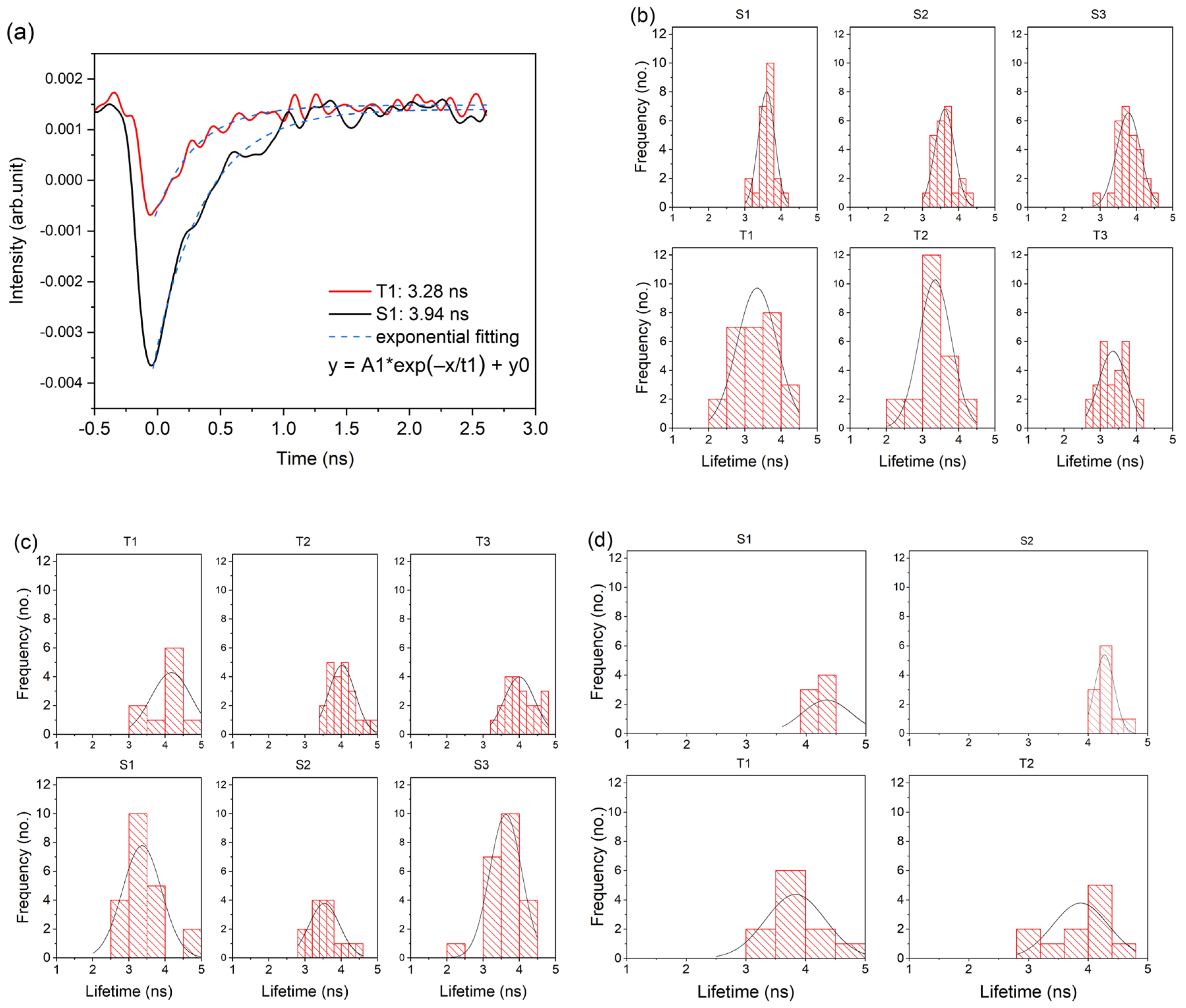

3.1.2. Fluorescence Lifetime

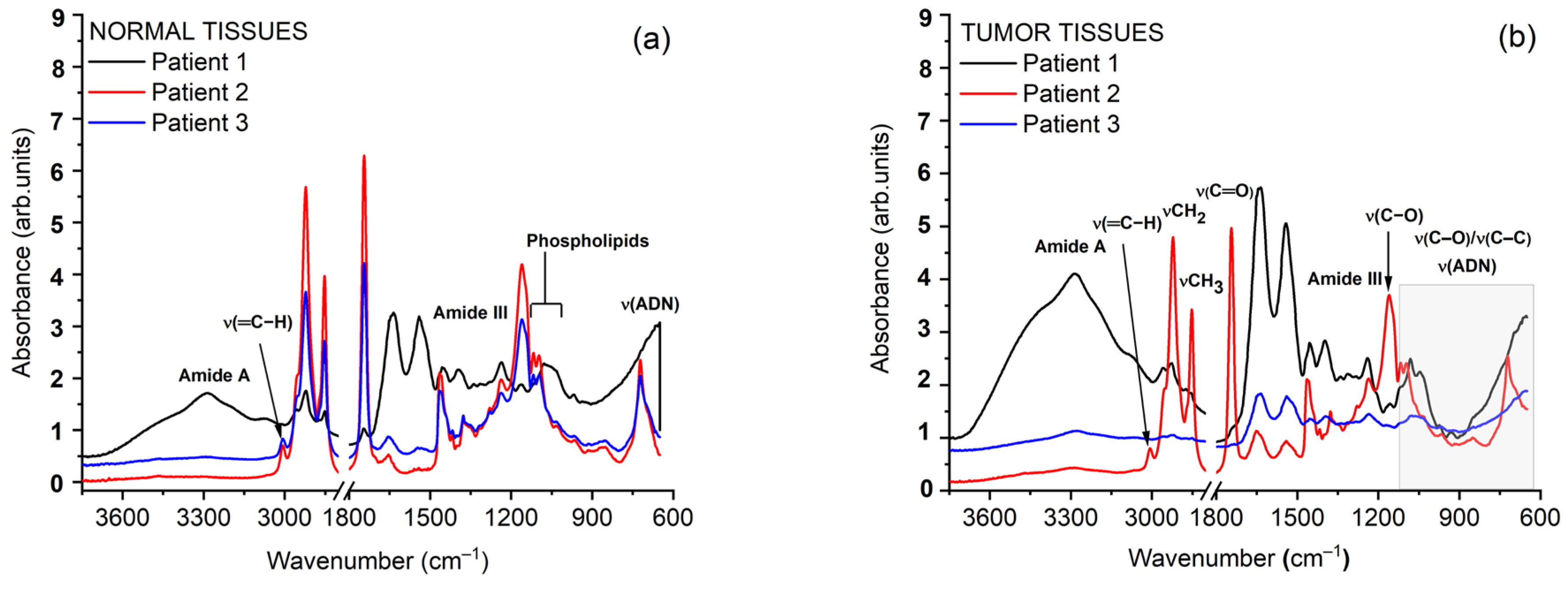

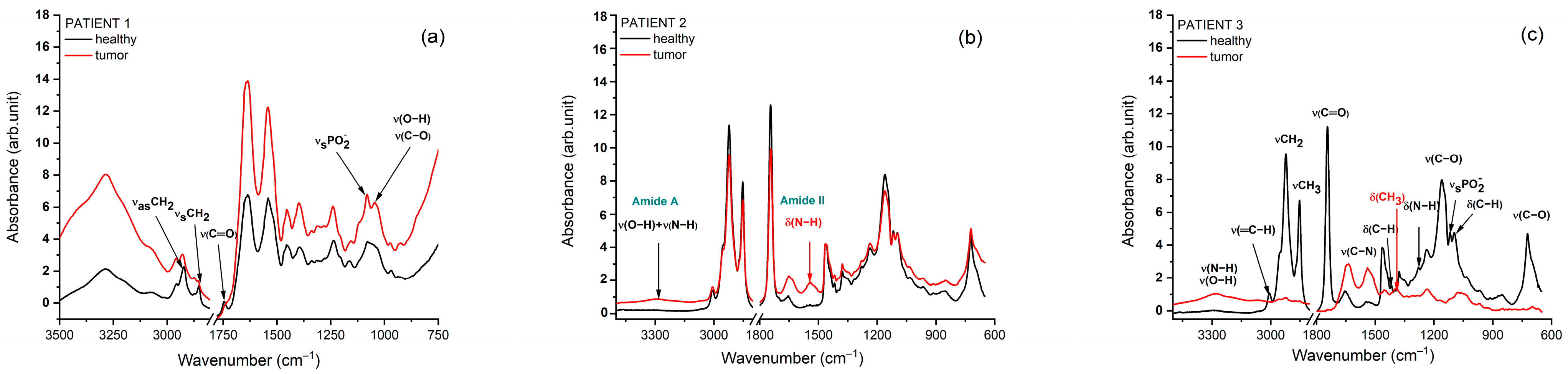

3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3.3. Biochemical Interpretation of Autofluorescence and FTIR Signatures Across Head and Neck Cancer Cases

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIAF | Laser-induced autofluorescence |

| HNC | Head and neck cancer |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| IR | Infrared |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced form |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance statistical method |

| FTIR-ATR | FTIR–attenuated total reflectance |

| ORL | Otorhinolaryngology |

| ENT | Ear, nose, and throat |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.N.S.; Amorim Dos Santos, J.; Coletta, R.D.; De Luca Canto, G. Strategies for evidence-based in head and neck cancer: Practical examples in developing systematic review questions. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1350535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.D.; Rocco, J.W.; Yom, S.S.; Haddad, R.I.; Saba, N.F. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, K.K.; Harris, J.; Wheeler, R.; Weber, R.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tân, P.F.; Westra, W.H.; Chung, C.H.; Jordan, R.C.; Lu, C.; et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Khan, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics. In Cancer Rehabilitation, 2nd ed.; Stubblefield, M.D., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, C.S.; Woo, S.; Zain, R.B.; Sklavounou, A.; McCullough, M.J.; Lingen, M. Oral Cancer and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 853479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speight, P.M.; Khurram, S.A.; Kujan, O. Oral potentially malignant disorders: Risk of progression to malignancy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 125, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.L.; Romo, L.; Hashmi, S. Malignant tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx: Clinical, pathologic, and radiologic evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2003, 13, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zima, A.J.; Wesolowski, J.R.; Ibrahim, M.; Lassig, A.A.D.; Lassig, J.; Mukherji, S.K. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Oropharyngeal Cancer. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 18, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, D.; Pruthy, R.; Pawar, U.; Chaturvedi, P. Oral cancer: Premalignant conditions and screening—An update. J. Can. Res. Ther. 2012, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkoumelis, N.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy of Bone Tissue: Bone Quality Assessment in Preclinical and Clinical Applications of Osteoporosis and Fragility Fracture. Clin. Rev. Bone Min. Metab. 2019, 17, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-J.; Huang, T.-W.; Cheng, N.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-F.; Tsai, M.-H.; Chiou, J.-C.; Duann, J.-R.; Lin, Y.-J.; Yang, C.-S.; Ou-Yang, M. Portable LED-induced autofluorescence spectroscopy for oral cancer diagnosis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, A.C.; Bottiroli, G. Autofluorescence spectroscopy and imaging: A tool for biomedical research and diagnosis. Eur. J. Histochem. 2014, 58, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenahora, M.R.; Peraza-L, A.; Díaz-Báez, D.; Bustillo, J.; Santacruz, I.; Trujillo, T.G.; Lafaurie, G.I.; Chambrone, L. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical visualization and light-based tests in precancerous and cancerous lesions of the oral cavity and oropharynx: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniyala Melanthota, S.; Kistenev, Y.V.; Borisova, E.; Ivanov, D.; Zakharova, O.; Boyko, A.; Vrazhnov, D.; Gopal, D.; Chakrabarti, S.; K, S.P.; et al. Types of spectroscopy and microscopy techniques for cancer diagnosis: A review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3067–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Long, F.; Tang, F.; Jing, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, L.; Ma, J.; Fei, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, G.; et al. Autofluorescence Imaging and Spectroscopy of Human Lung Cancer. Appl. Sci. 2016, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozar, T.; Andrei, I.R.; Costin, R.; Pirvulescu, R.; Pascu, M.L. Case series about ex vivo identification of squamous cell carcinomas by laser-induced autofluorescence and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozar, T.; Andrei, I.R.; Costin, R.; Pascu, M.L.; Pirvulescu, R. Laser induced autofluorescence lifetime to identify larynx squamous cell carcinoma: Short series ex vivo study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 202, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucht, R.P. Applications of laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy for combustion and plasma diagnostics. In Laser Spectroscopy and Its Applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1987; pp. 623–676. [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, R.; Tata, D.; Cordero, J.; Tomashefsky, P.; Longo, F.; Alfano, M. Laser induced fluorescence spectroscopy from native cancerous and normal tissue. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1984, 20, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, J.; Zachem, T.J.; Prakash, R.; Owolo, E.; Yamamoto, K.; Nguyen, A.D.; Hockenberry, H.; Ross, W.A.; Herndon, J.E.; Codd, P.J.; et al. A blinded study using laser induced endogenous fluorescence spectroscopy to differentiate ex vivo spine tumor, healthy muscle, and healthy bone. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.; Newport, E.; Morten, K.J. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachem, T.J.; Komisarow, J.M.; Hachem, R.A.; Jang, D.W.; Ross, W.; Codd, P.J. Intraoperative Ex Vivo Pituitary Adenoma Subtype Classification Using Noncontact Laser Fluorescence Spectroscopy. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2023, 84, S1–S344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithran, M.S.; Lukose, J.; Barik, B.K.; Periasami, A.; Kartha, V.B.; Chawla, A.; Chidangil, S. Laser induced fluorescence spectroscopy analysis of kidney tissues: A pilot study for the identification of renal cell carcinoma. J. Biophotonics 2023, 16, e202300021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Naidu, A.; Wang, Y. Oral Cancer Discrimination and Novel Oral Epithelial Dysplasia Stratification Using FTIR Imaging and Machine Learning. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, E.; Hole, A.; Deshmukh, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Chilakapati, M.K.; Mora, B.; Roy, D. Improving Vibrational Spectroscopy Prospects in Frontline Clinical Diagnosis: Fourier Transform Infrared on Buccal Mucosa Cancer. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 13642–13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.-Y.; Lee, W.-L. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy as a Cancer Screening and Diagnostic Tool: A Review and Prospects. Cancers 2020, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczak, M.; Wróbel, A.; Surman, M.; Durak-Kozica, M.; Stępień, E.Ł.; Przybyło, M. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy as a reliable analytical tool in cancer research: Tracking glycosylation-induced protein and lipid alteration in extracellular vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2026, 1873, 120082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas, R.C.; Sayat, A.J.; Atienza, A.N.; Danganan, J.L.; Ramos, M.R.; Fellizar, A.; Notarte, K.I.; Angeles, L.M.; Bangaoil, R.; Santillan, A.; et al. Detection of breast cancer by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy using artificial neural networks. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangaoil, R.; Santillan, A.; Angeles, L.M.; Abanilla, L.; Lim, A.; Ramos, M.C.; Fellizar, A.; Guevarra, L.; Albano, P.M. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy as adjunct method to the microscopic examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissues in diagnosing lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, F. Fluorescence microscopy, applications. In Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzahn, K.; Dreyer, T.; Glanz, H.; Arens, C. Autofluorescence Endoscopy in the Diagnosis of Early Laryngeal Cancer and Its Precursor Lesions. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarto, J.L.; Credi, C.; Villa, F.; Tisa, S.; Zappa, F.; Shcheslavskiy, V.; Pavone, F.S.; Cicchi, R. Multispectral Depth-Resolved Fluorescence Lifetime Spectroscopy Using SPAD Array Detectors and Fiber Probes. Sensors 2019, 19, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, H. Methods to study protein folding by stopped-flow FT-IR. Methods 2004, 34, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benseny-Cases, N.; Klementieva, O.; Cotte, M.; Ferrer, I.; Cladera, J. Microspectroscopy (μFTIR) Reveals Co-localization of Lipid Oxidation and Amyloid Plaques in Human Alzheimer Disease Brains. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 12047–12054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, H.; Garlapati, C.; Janssen, E.A.M.; Krishnamurti, U.; Qin, G.; Aneja, R.; Perera, A.G.U. Protein Conformational Changes in Breast Cancer Sera Using Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Martin, F.L. Discrimination of Base Differences in Oligonucleotides Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy and Multivariate Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 5314–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petibois, C.; Déléris, G. Evidence that erythrocytes are highly susceptible to exercise oxidative stress: FT-IR spectrometric studies at the molecular level. Cell Biol. Int. 2005, 29, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qu, J.Y. Autofluorescence spectroscopy of epithelial tissues. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11, 054023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, C.S.; Mehlmann, M.; Rick, K.; Stepp, H.; Grevers, G.; Baumgartner, R.; Leunig, A. Autofluorescence imaging and spectroscopy of normal and malignant mucosa in patients with head and neck cancer. Lasers Surg. Med. 1999, 25, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, I.A.; Grusha, I.O.; Kiriushchenkova, N.P. Autofluorescent diagnostics of skin and mucosal tumors. Vestn. Oftalmol. 2013, 129, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam, N.; Richards-Kortum, R.; Thomsen, S.; Mahadevan-Jansen, A.; Follen, M.; Chance, B. Low temperature fluorescence imaging of freeze-trapped human cervical tissues. Opt. Express 2001, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczona, R.; Temam, S.; Janot, F.; Marandas, P.; Luboinski, B. Autofluorescence videoendoscopy for photodiagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2003, 260, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmanova, M.V.; Sachkova, D.A.; Shchechkin, I.D.; Kiseleva, E.B.; Komarova, A.D.; Kuhnina, L.S.; Grishin, A.S.; Bederina, E.L.; Pyanova, E.V.; Ponomareva, E.E.; et al. Optical express-biopsy of gliomas using macroscopic fluorescence lifetime imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2025, 16, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suraci, D.; Tirloni, L.; Gatto, C.; Pillozzi, S.; Antonuzzo, L.; Taddei, A.; Cicchi, R. Optical diagnostics of liver tumors using an autofluorescence lifetime probe. Biomed. Opt. Express 2025, 16, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, J.; Hebisch, C.; Phipps, J.E.; Lagarto, J.L.; Kim, H.; Darrow, M.A.; Bold, R.J.; Marcu, L. Real-time diagnosis and visualization of tumor margins in excised breast specimens using fluorescence lifetime imaging and machine learning. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy in Oral Cancer Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Martinez, M.A.G.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Advances in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2017, 52, 456–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Ur Rehman, I. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-C.; Lo, Y.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Sheu, H.-M.; Lin, J.-C. Feasibility of rapid quantitation of stratum corneum lipid content by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. Spectroscopy 2004, 18, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantsch, H.H.; McElhaney, R.N. Phospholipid phase transitions in model and biological membranes as studied by infrared spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1991, 57, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, F.; Hildebrandt, P. Vibrational Spectroscopy in Life Science, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiercigroch, E.; Szafraniec, E.; Czamara, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Majzner, K.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M.; Malek, K. Raman and infrared spectroscopy of carbohydrates: A review. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 185, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotogorski-Hurvitz, A.; Dekel, B.Z.; Malonek, D.; Yahalom, R.; Vered, M. FTIR-based spectrum of salivary exosomes coupled with computational-aided discriminating analysis in the diagnosis of oral cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Garcia, V.; Ten-Doménech, I.; Moreno-Giménez, A.; Gormaz, M.; Parra-Llorca, A.; Shephard, A.P.; Sepúlveda, P.; Pérez-Guaita, D.; Vento, M.; Lendl, B.; et al. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy for the routine quality control of exosome isolations. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2021, 217, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentirmai, V.; Wacha, A.; Németh, C.; Kitka, D.; Rácz, A.; Héberger, K.; Mihály, J.; Varga, Z. Reagent-free total protein quantification of intact extracellular vesicles by attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 4619–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, L.; Federici, S.; Consoli, G.; Arceri, D.; Radeghieri, A.; Alessandri, I.; Bergese, P. Fourier-transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy fingerprints subpopulations of extracellular vesicles of different sizes and cellular origin. J. Extracell. Vesicle 2020, 9, 1741174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Yang, S.; Kong, J.; Dong, A.; Yu, S. Obtaining information about protein secondary structures in aqueous solution using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovbeshko, G. FTIR spectroscopy studies of nucleic acid damage. Talanta 2000, 53, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckel, R.; Huo, H.; Guan, H.-W.; Hu, X.; Che, X.; Huang, W.-D. Characteristic infrared spectroscopic patterns in the protein bands of human breast cancer tissue. Vib. Spectrosc. 2001, 27, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.C.O.; Silva, P.P.; Morais, C.L.M.; Miranda, C.G.; Crispim, J.C.O.; Lima, K.M.G. ATR-FTIR and multivariate analysis as a screening tool for cervical cancer in women from northeast Brazil: A biospectroscopic approach. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 99648–99655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnas, E.; Skret-Magierlo, J.; Skret, A.; Kaznowska, E.; Depciuch, J.; Szmuc, K.; Łach, K.; Krawczyk-Marć, I.; Cebulski, J. Simultaneous FTIR and Raman Spectroscopy in Endometrial Atypical Hyperplasia and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, E.Ł.; Kamińska, A.; Surman, M.; Karbowska, D.; Wróbel, A.; Przybyło, M. Fourier-Transform InfraRed (FT-IR) spectroscopy to show alterations in molecular composition of EV subpopulations from melanoma cell lines in different malignancy. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 25, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.-W.; Mak, S.-H.; Goh, B.-H.; Lee, W.-L. The Convergence of FTIR and EVs: Emergence Strategy for Non-Invasive Cancer Markers Discovery. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, C.; Soloway, R.D.; Xu, D.; Wu, Q.; Sun, K.; Weng, S.; Xu, G. Distinguishing malignant from normal oral tissues using FTIR fiber-optic techniques. Biopolymers 2001, 62, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, H.; Jackson, M.; Murphy, L.; Watson, P.H.; Fichtner, I.; Mantsch, H.H. A comparative infrared spectroscopic study of human breast tumors and breast tumor cell xenografts. Biospectroscopy 1995, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Nakanishi, M.; Rajan, R.; Nakagawa, H. Protein hydration and its freezing phenomena: Toward the application for cell freezing and frozen food storage. Biophysics 2021, 18, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Chu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Effects of Different Freezing Methods on Water Distribution, Microstructure and Protein Properties of Cuttlefish during the Frozen Storage. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyng, F.; Gazi, E.; Gardner, P. Preparation of Tissues and Cells for Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy and Imaging; Technological University Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Allen, H.C. Developing transferable and universal IR biomarkers for intraoperative colorectal cancer diagnosis via FTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanujam, N. Fluorescence Spectroscopy of Neoplastic and Non-Neoplastic Tissues. Neoplasia 2000, 2, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentioned in text | Maxillary sinus | Base of the tongue with extension toward the hypopharynx | Right hemilingual mass |

| ORL clinical examination |

|

|

|

| Surgical intervention |

|

|

|

| Histopathological examination | Epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma with focally increased mitotic activity. | Well-differentiated microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma with high-grade dysplastic lesions of the adjacent epithelium. | Poorly keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma G3. |

| Patient ID | Tissue Type | Samples | No. of Scan Points | Mean Peak Intensity | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | S1 | 24 | 148,191.15 | 32,283.26 |

| S2 | 24 | 124,078.37 | 21,970.90 | ||

| S3 | 27 | 201,154.38 | 91,306.33 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 157,807.97 ± 39,427.65 | ||||

| 1 | Malignant | T1 | 26 | 82,514.99 | 12,168.71 |

| T2 | 23 | 95,433.43 | 21,019.97 | ||

| T3 | 26 | 71,049.40 | 14,290.67 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 82,999.28 ± 12,199.22 | ||||

| p-value = 0.0348 | |||||

| 2 | Normal | S1 | 19 | 108,512.66 | 50,875.09 |

| S2 | 21 | 106,251.003 | 59,025.10 | ||

| S3 | 22 | 108,571.45 | 58,276.22 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 107,778.37598 ± 1323.0702 | ||||

| 2 | Malignant | T1 | 15 | 79,757.86 | 15,729.27 |

| T2 | 21 | 72,489.88 | 16,004.62 | ||

| T3 | 20 | 78,720.01 | 21,242.98 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 76,989.25334 ± 3930.97036 | ||||

| p-value = 0.00021 | |||||

| 3 | Normal | S1 | 12 | 111,449.09 | 69,545.67 |

| S2 | 15 | 102,901.70 | 32,160.80 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 107,175.40 ± 6043.91 | ||||

| 3 | Malignant | T1 | 15 | 72,810.19 | 19,227.37 |

| T2 | 13 | 83,119.53 | 25,420.96 | ||

| Mean intensity ± SD | 77,964.86 ± 7289.80 | ||||

| p-value = 0.04874 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stăncălie-Nedelcu, R.I.; Berteșteanu, Ș.V.G.; Berteșteanu, G.S.; Andrei, I.R.; Smarandache, A.; Staicu, A.; Tozar, T.; Costin, R.; Grigore, R. Exploratory Approach Using Laser-Induced Autofluorescence for Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer Diagnosis—Three Case Reports. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031536

Stăncălie-Nedelcu RI, Berteșteanu ȘVG, Berteșteanu GS, Andrei IR, Smarandache A, Staicu A, Tozar T, Costin R, Grigore R. Exploratory Approach Using Laser-Induced Autofluorescence for Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer Diagnosis—Three Case Reports. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031536

Chicago/Turabian StyleStăncălie-Nedelcu, Ruxandra Ioana, Șerban Vifor Gabriel Berteșteanu, Gloria Simona Berteșteanu, Ionuț Relu Andrei, Adriana Smarandache, Angela Staicu, Tatiana Tozar, Romeo Costin, and Raluca Grigore. 2026. "Exploratory Approach Using Laser-Induced Autofluorescence for Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer Diagnosis—Three Case Reports" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031536

APA StyleStăncălie-Nedelcu, R. I., Berteșteanu, Ș. V. G., Berteșteanu, G. S., Andrei, I. R., Smarandache, A., Staicu, A., Tozar, T., Costin, R., & Grigore, R. (2026). Exploratory Approach Using Laser-Induced Autofluorescence for Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancer Diagnosis—Three Case Reports. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031536