Experimental Investigation and Predictive Modeling of Surface Roughness in Dry Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Using Power-Law and Response Surface Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

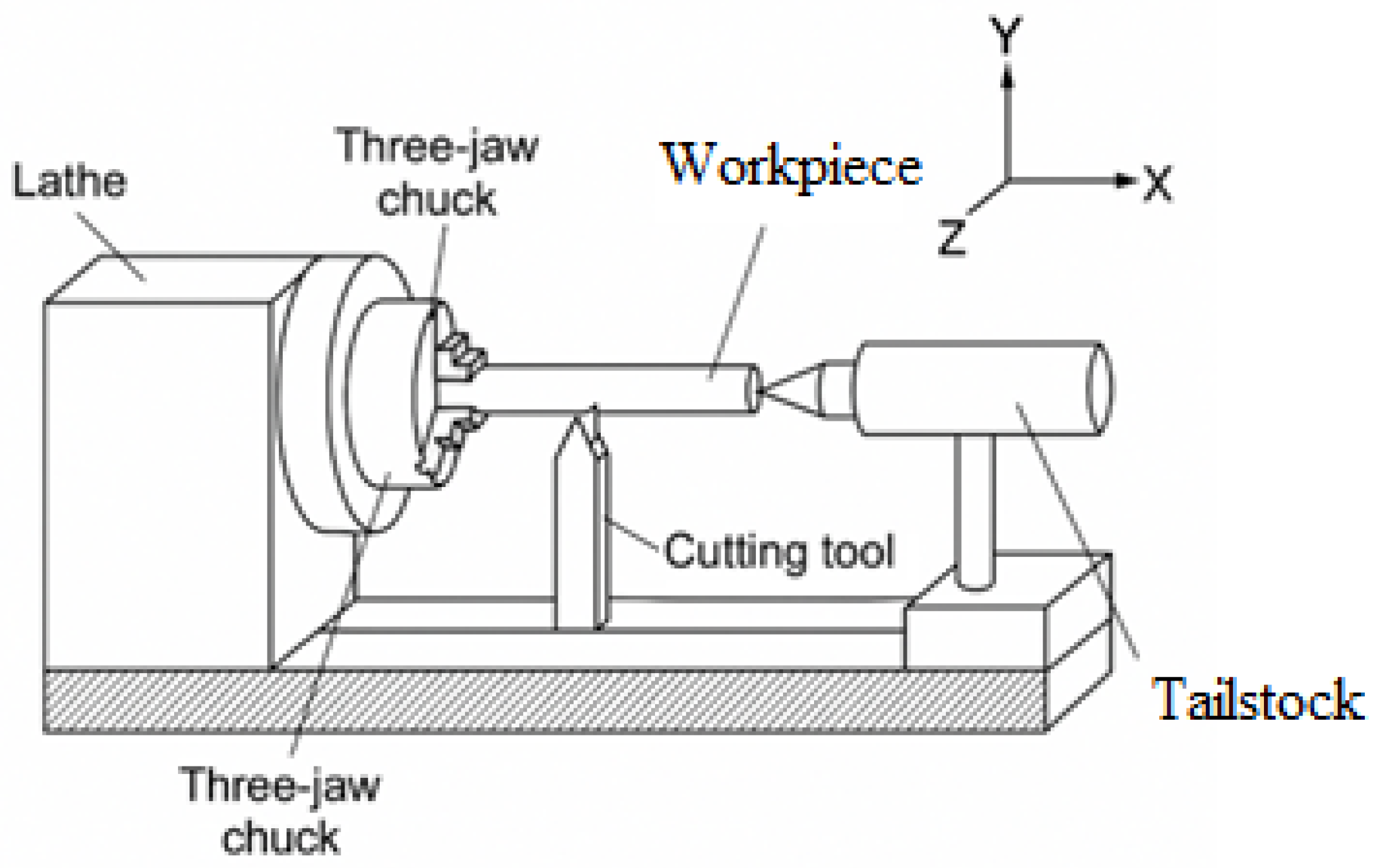

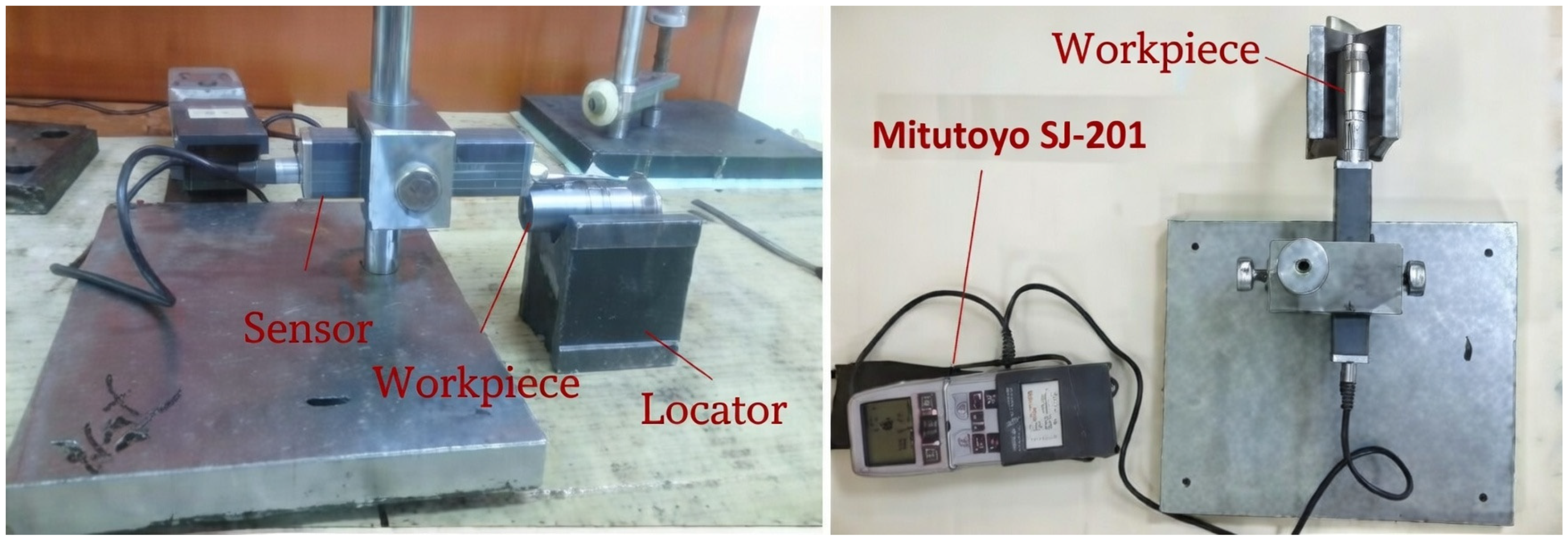

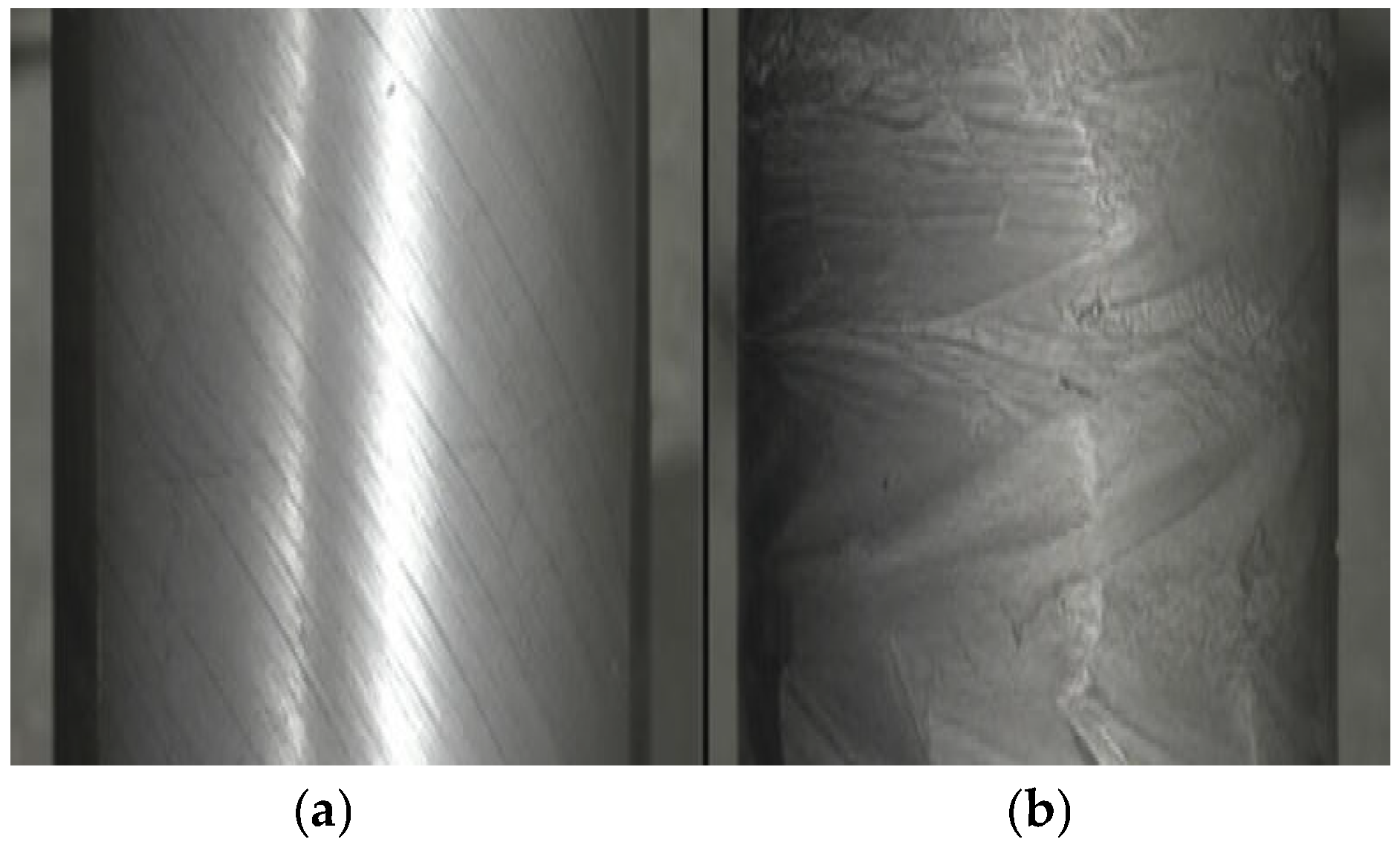

2.1. Workpiece, Tool, Machine, and Measurement

2.2. Design of Experiments

2.3. Statistical Modeling Strategy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Baseline Power-Law Model

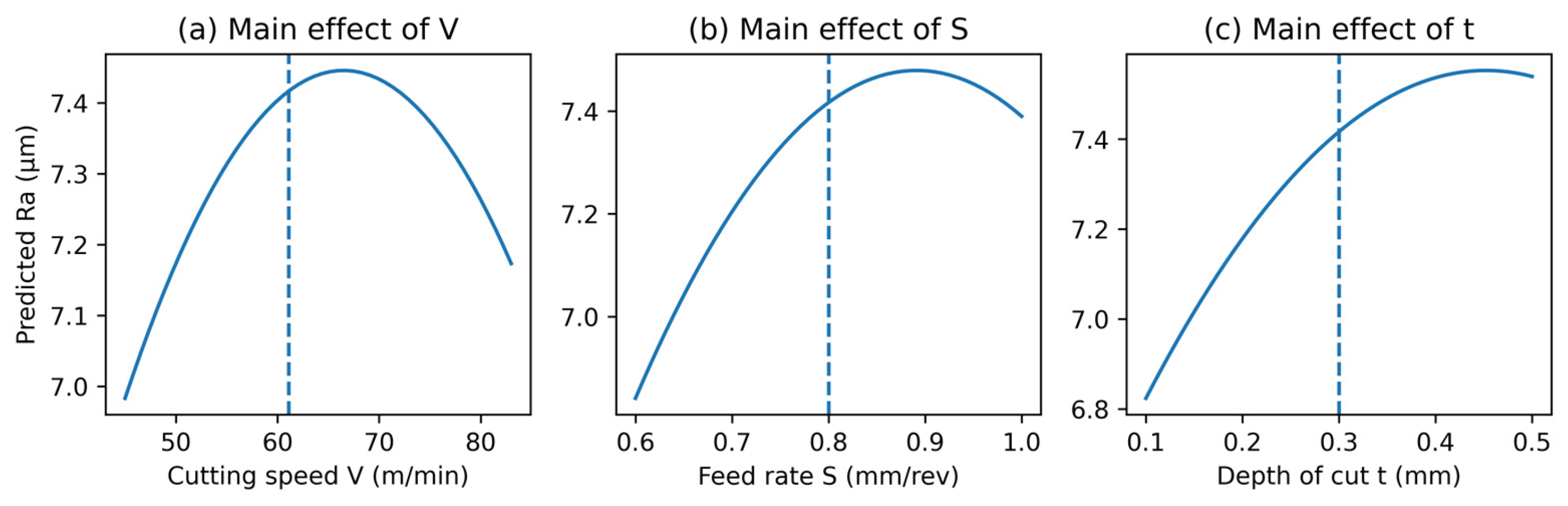

3.2. Main Effects

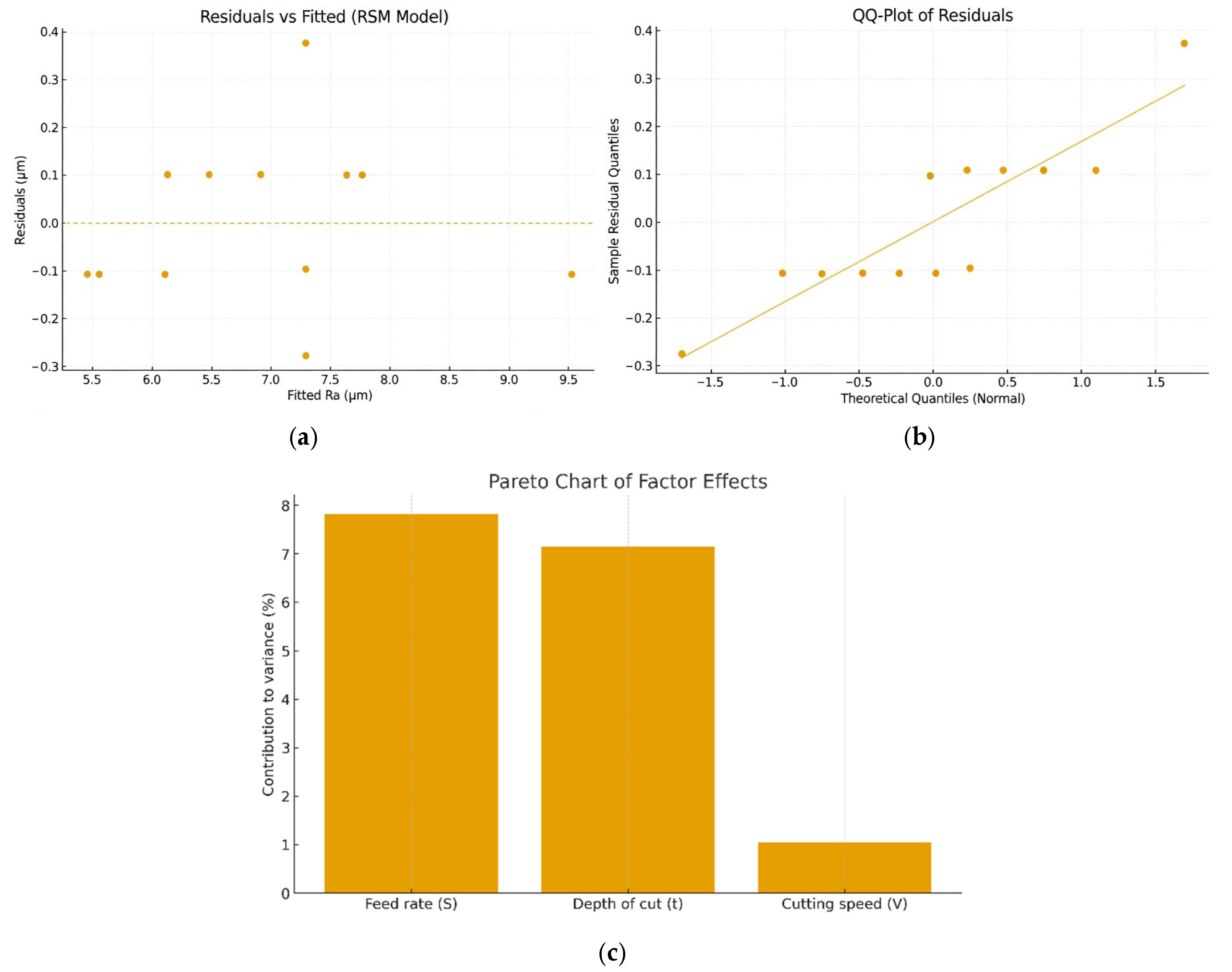

3.3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

3.4. Lasso-Regularized Model

3.5. Residual Diagnostics

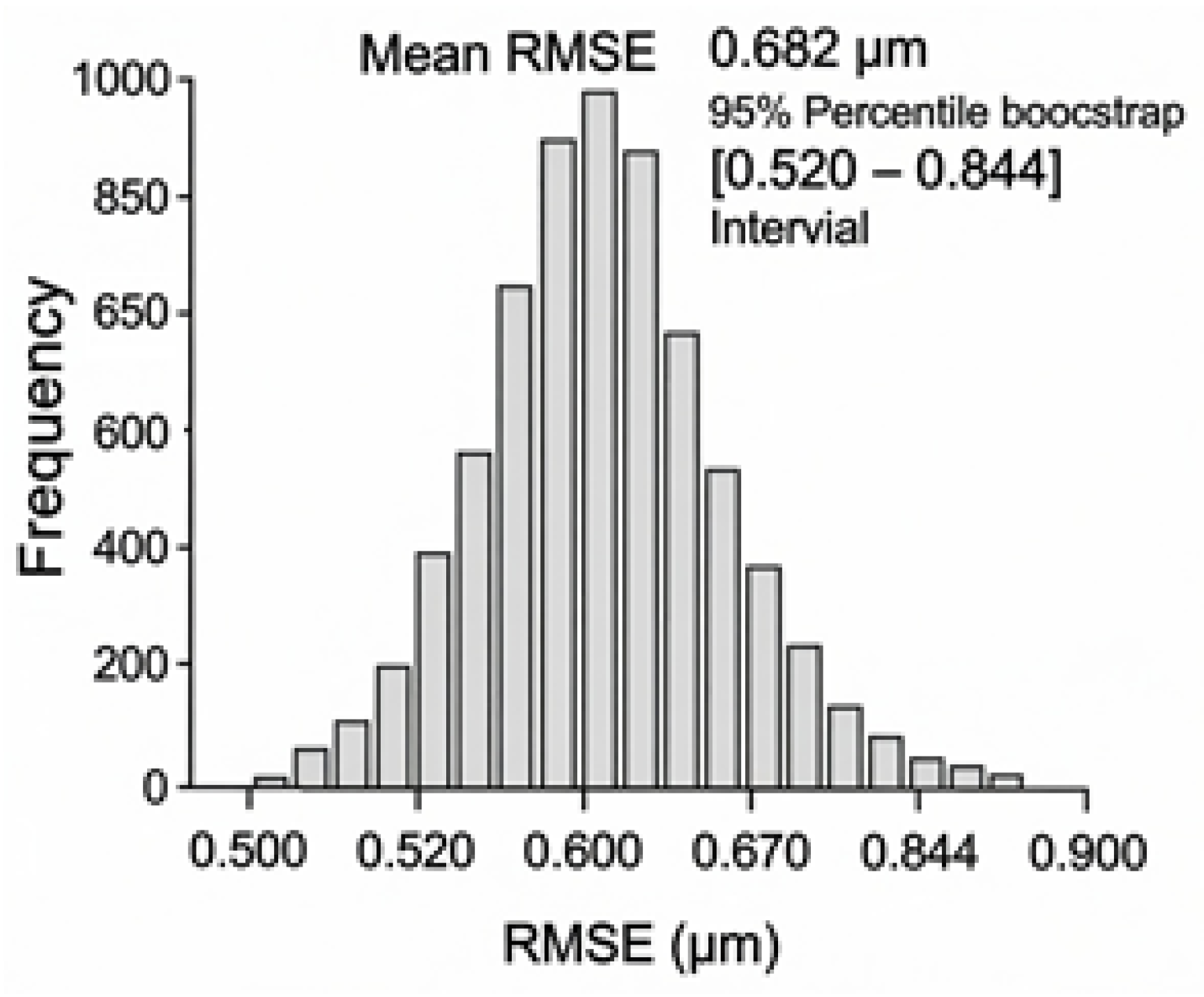

3.6. Confidence and Uncertainty Analysis (PRESS, LOOCV, Bootstrap)

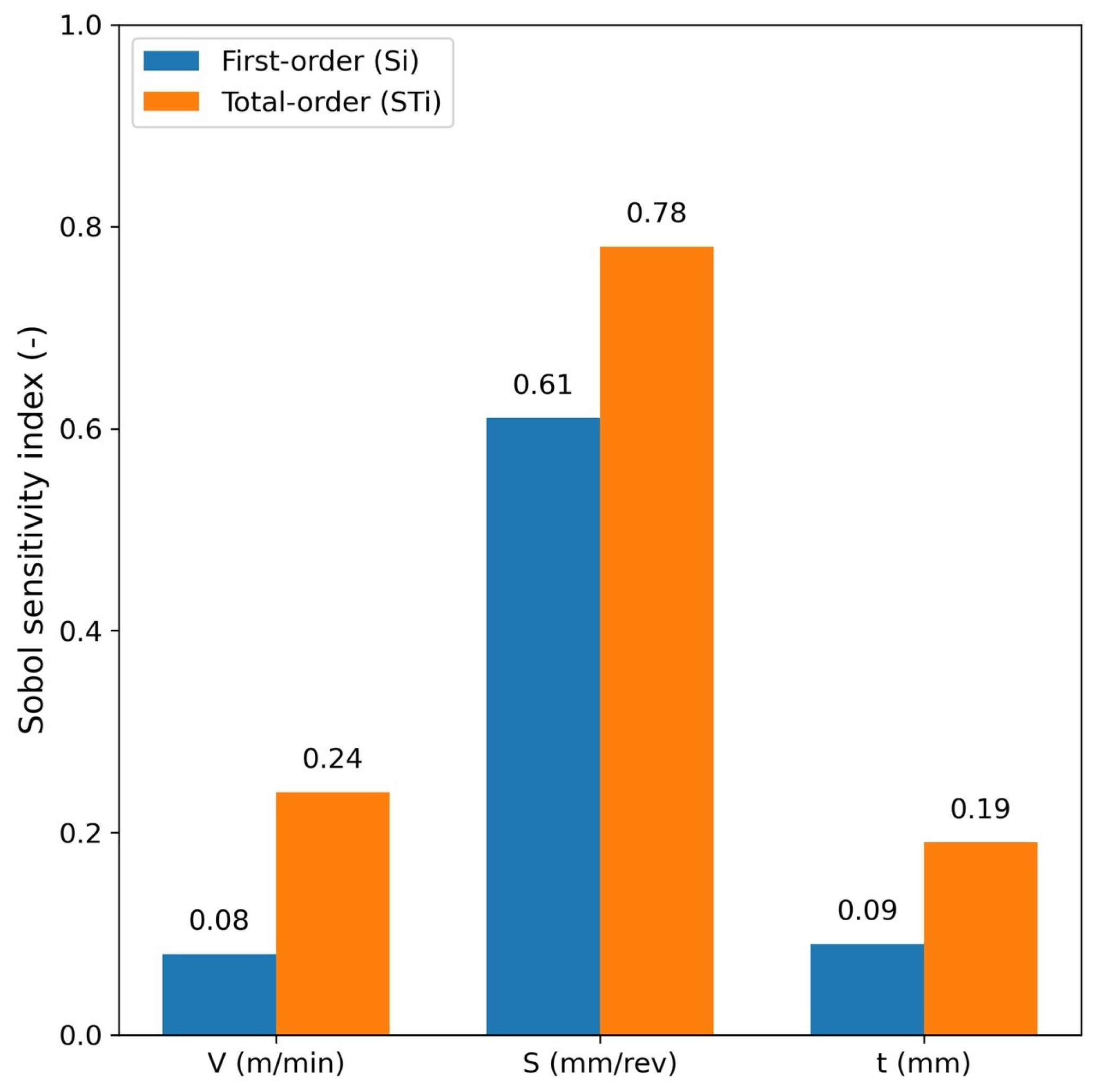

3.7. Global Sensitivity Analysis (Sobol Indices)

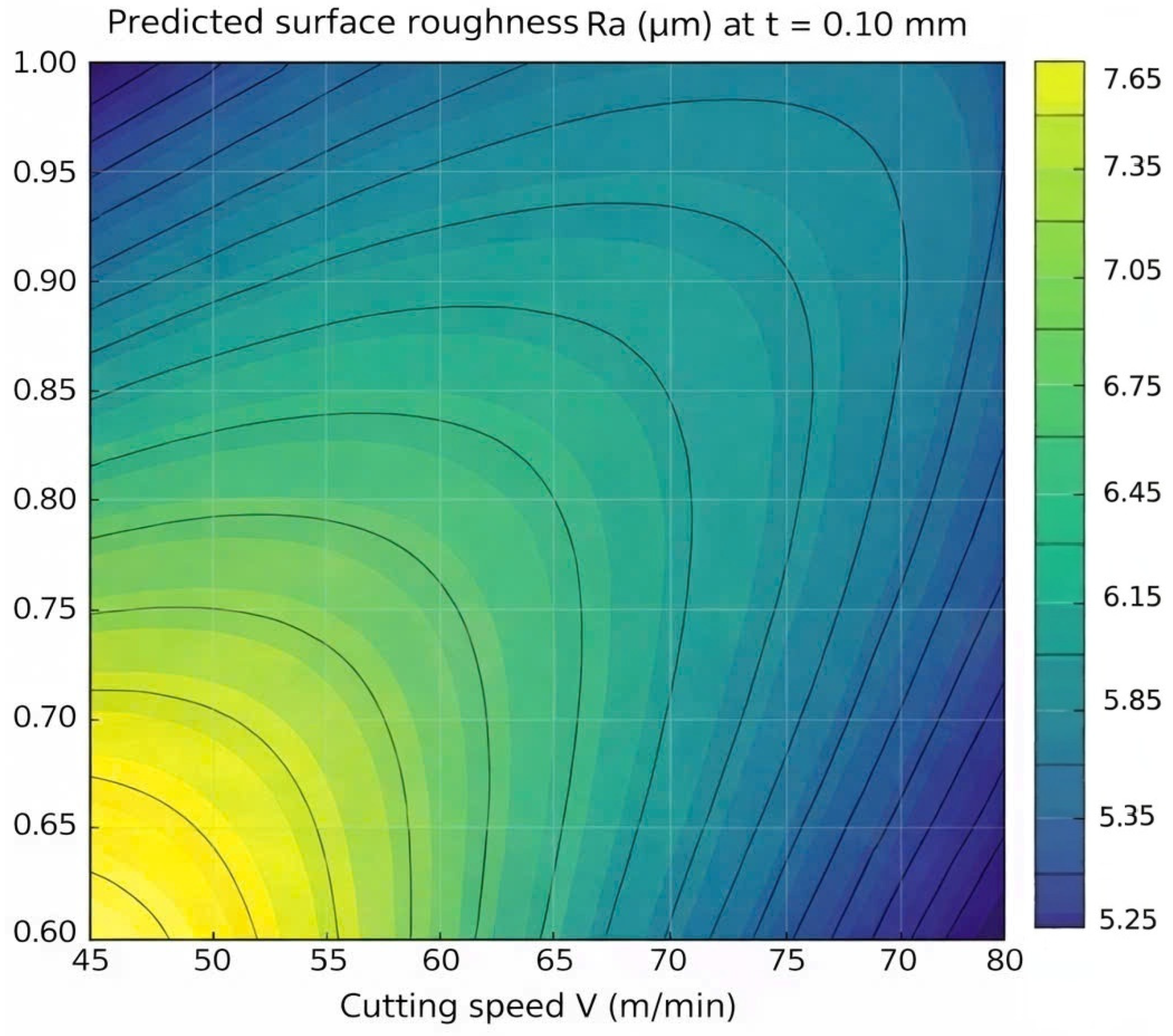

4. Optimization and Practical Implications

4.1. Identification of Optimal Conditions and Discussion on Minimum Roughness

4.2. Practical Implications for Industrial Application

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davim, J.P. Machining of Hard Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhov, V.P. Tribology of Metal Cutting; Elsevier: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-444-52882-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, M.H.M.; Mazlan, A.Z.A.; Wei, L.M.; Tying, C.T.; Sze, T.S.; Jamil, N.I.M. Effect of Machining Parameters on Surface Roughness for Different Type of Materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 530, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajemi, M.F.; Mativenga, P.T.; Aramcharoen, A. Sustainable machining: Selection of optimum turning conditions based on minimum energy considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.; Dhar, N.R. Prediction of Surface Roughness in Hard Turning. Measurement 2016, 92, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhesana, M.A.; Bagga, P.J.; Patel, K.M.; Taha-Tijerina, J.J. Effects of Machining Parameters of C45 Steel Applying Vegetable Lubricant with Minimum Quantity Cooling Lubrication (MQCL). Lubricants 2023, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntoğlu, M.; Acar, O.; Gupta, M.K.; Sağlam, H.; Sarikaya, M.; Giasin, K.; Pimenov, D.Y. Parametric Optimization for Cutting Forces and Material Removal Rate in the Turning of AISI 5140. Machines 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M.; Joudaki, J.; Emadi, M. Surface quality in dry machining of 55Cr3 steel bars. Int. J. Iron Steel Soc. Iran 2018, 15, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Makadia, J.I.; Nanavati, A.J. Optimization of machining parameters for turning operations based on response surface methodology. Measurement 2013, 46, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, L.C.; Carlesso, G.C.; López de Lacalle, L.N.; Souza, M.T.; de Oliveira Palheta, F.; Binder, C. Tool Wear Effect on Surface Integrity in AISI 1045 Steel Dry Turning. Materials 2022, 15, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, T.; Chattopadhyay, A.K. Dry turning performance of TiN–WSx/TiN hard-lubricious bilayer composite coating. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2020, 24, 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagandran, V.; Janahiraman, T.V.; Ahmad, N. Modeling and Optimization of Carbon Steel AISI 1045 Surface Roughness in CNC Turning Based on RSM and Heuristic Optimization Algorithms. Am. J. Neural Netw. Appl. 2018, 3, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordin, M.Y.; Venkatesh, V.C.; Sharif, S.; Elting, S.; Abdullah, A. Application of response surface methodology in describing the performance of coated carbide tools when turning AISI 1045 steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 145, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felho, C.; Varga, G. Theoretical Roughness Modeling of Hard Turned Surfaces Considering Tool Wear. Machines 2022, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antosz, K.; Kozłowski, E.; Sęp, J.; Prucnal, S. Application of Machine Learning to the Prediction of Surface Roughness in the Milling Process on the Basis of Sensor Signals. Materials 2025, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahiuddin, I.; Fatr, J.; Milde, R.; Pata, V.; Ubaidillah, U.; Mazlan, S.A.; Sedlacik, M. Machine learning-based surface roughness prediction in magnetorheological finishing of polyamide influenced by initial conditions. Process 2025, 121, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, J.; Zhang, M.; Lin, Q. Predicting Surface Roughness in Turning Complex-Structured Workpieces Using Vibration-Signal-Based Gaussian Process Regression. Sensors 2024, 24, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Che, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, C. Uncertainty Quantification and Optimal Robust Design for Machining Operations. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 23, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21920-2:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile—Part 2: Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- ISO 21920-3:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile—Part 3: Specification Operators. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Anh, L.H.; Linh, N.H.; Cuong, D.Q.; Danh, B.T.; Quang, N.H.; Tuan, N.A. Study on Productivity Improvement When Turning AISI 1045 Steel on Basis of Surface Roughness Assurance. In Advances in Engineering Research and Application, Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Research and Applications, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam, 1–2 December 2022; Nguyen, D.C., Hai, D.T., Vu, N.P., Long, B.T., Puta, H., Sattler, K.-U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, B.; Islam, M.N.; Davies, I.J.; Ginting, Y.R.; Ong, A.K. A Review of Dry Machining and Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL) in Turning Processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, S.; Bilga, P.S.; Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Scutaru, M.L.; Pruncu, C.I. Revealing the benefits of entropy weights method for multi-objective optimization in machining operations: A critical review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyambaş, Y.; Akdulum, A.; Çakıroğlu, R.; Uzun, G. Estimation of cutting temperature using machine learning based on signal information received from power analyzer in vortex machining conditions. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 137, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanical Properties | Value | Chemical Composition | Range (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | ~630 MPa | C | 0.43–0.50 |

| Yield Strength | ~530 MPa | Mn | 0.60–0.90 |

| Hardness | 170–210 HB | Si | 0.15–0.30 |

| Elastic Modulus | 210 GPa | P | ≤0.040 |

| Density | 7.85 g/cm3 | S | ≤0.050 |

| Run | V (m/min) | S (mm/rev) | t (mm) | Ra (µm) | Ra SD (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 9.43 | 0.18 |

| 2 | 45 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 6.89 | 0.15 |

| 3 | 83 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 6.06 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 45 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 6.01 | 0.13 |

| 5 | 83 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 6.47 | 0.14 |

| 6 | 45 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.44 | 0.11 |

| 7 | 83 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 5.35 | 0.10 |

| 8 | 45 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 7.68 | 0.16 |

| 9(C) | 61.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 7.02 | 0.12 |

| 10(C) | 61.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 7.34 | 0.14 |

| 11(C) | 61.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 7.67 | 0.13 |

| Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | 6.3877 | 0.824 | 49.58 | 0.069 |

| 0.0546 | −0.436 | 0.545 | 0.800 | |

| 0.2078 | −0.380 | 0.796 | 0.431 | |

| 0.0766 | −0.110 | 0.263 | 0.364 | |

| R2 (log-scale) | 0.196 | |||

| RMSE (log-scale) | 0.180 |

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | p-Value | % Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 23.45 | 2.605 | 12.34 | 0.001 | 97.8% |

| V | 1 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 5.82 | 0.052 | 5.1% |

| S | 1 | 14.78 | 14.78 | 70.00 | 0.000 | 61.5% |

| t | 1 | 2.56 | 2.56 | 12.12 | 0.018 | 10.6% |

| V2 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 2.13 | 0.195 | 1.9% |

| S2 | 1 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 17.38 | 0.009 | 15.3% |

| t2 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.481 | 0.5% |

| VS | 1 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 1.61 | 0.252 | 1.4% |

| Vt | 1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.538 | 0.4% |

| St | 1 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.358 | 0.9% |

| Error | 1 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 2.2% | ||

| Total | 10 | 24.06 | 100% |

| Term | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 11.804 | 6.421 |

| V | −0.059 | 0.119 |

| S | −3.354 | 6.008 |

| t | −15.935 | 12.113 |

| V2 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| S2 | −7.525 | 3.377 |

| t2 | −5.871 | 6.763 |

| VS | 0.192 | 0.074 |

| Vt | 0.128 | 0.074 |

| St | 16.781 | 14.885 |

| Metric | Value (µm) |

|---|---|

| In-sample RMSE | 0.319 |

| LOOCV RMSE | 0.771 |

| Bootstrap mean RMSE | 0.682 |

| 95% CI | [0.52, 0.84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vu, T.-H.; Hsu, C.-H. Experimental Investigation and Predictive Modeling of Surface Roughness in Dry Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Using Power-Law and Response Surface Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031392

Vu T-H, Hsu C-H. Experimental Investigation and Predictive Modeling of Surface Roughness in Dry Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Using Power-Law and Response Surface Approaches. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031392

Chicago/Turabian StyleVu, Thanh-Hung, and Cheung-Hwa Hsu. 2026. "Experimental Investigation and Predictive Modeling of Surface Roughness in Dry Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Using Power-Law and Response Surface Approaches" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031392

APA StyleVu, T.-H., & Hsu, C.-H. (2026). Experimental Investigation and Predictive Modeling of Surface Roughness in Dry Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Using Power-Law and Response Surface Approaches. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031392