Theoretical Analysis of the Vertical Stability of a Floating and Sinking Drilled Wellbore Using Vertical Elastic Supports

Abstract

1. Introduction

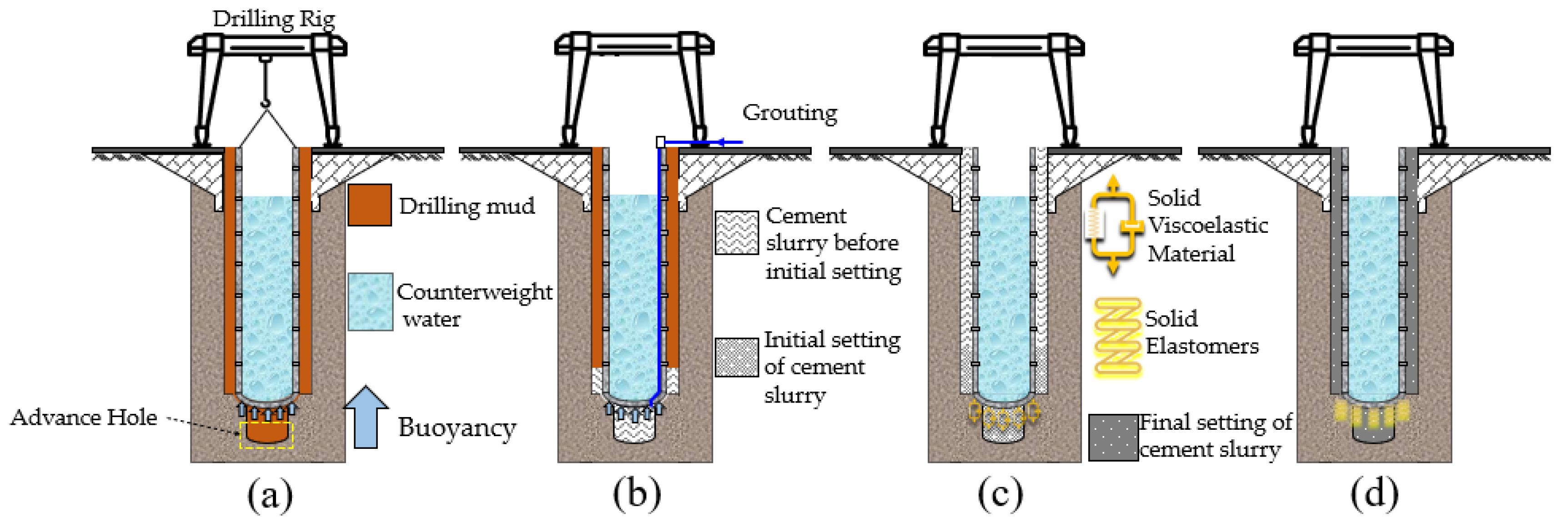

2. Analysis of Stress Evolution of Bottom Filling of Shaft Lining

2.1. Analysis of the Stress Evolution of Bottom Filling in Wellbore Walls

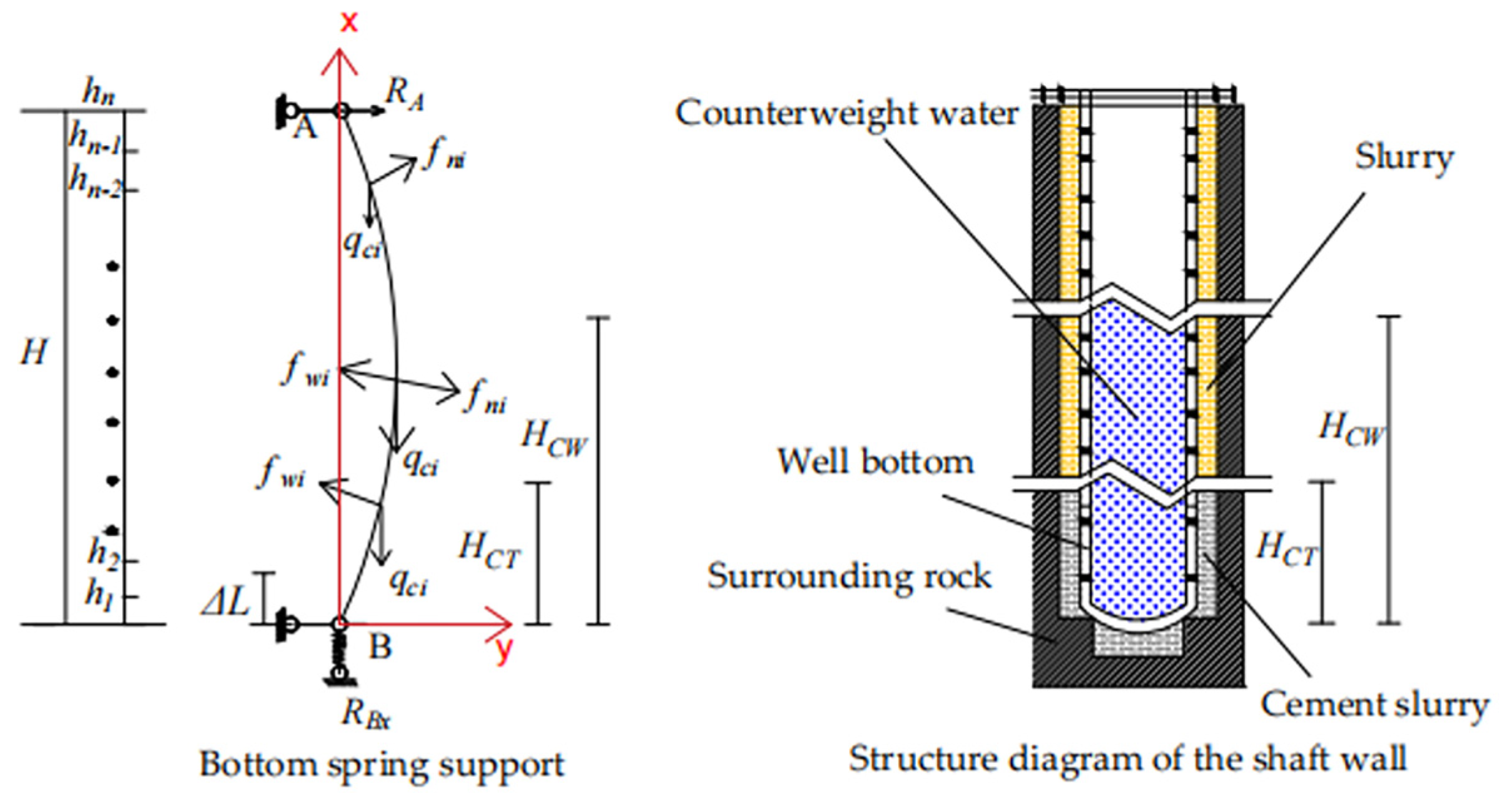

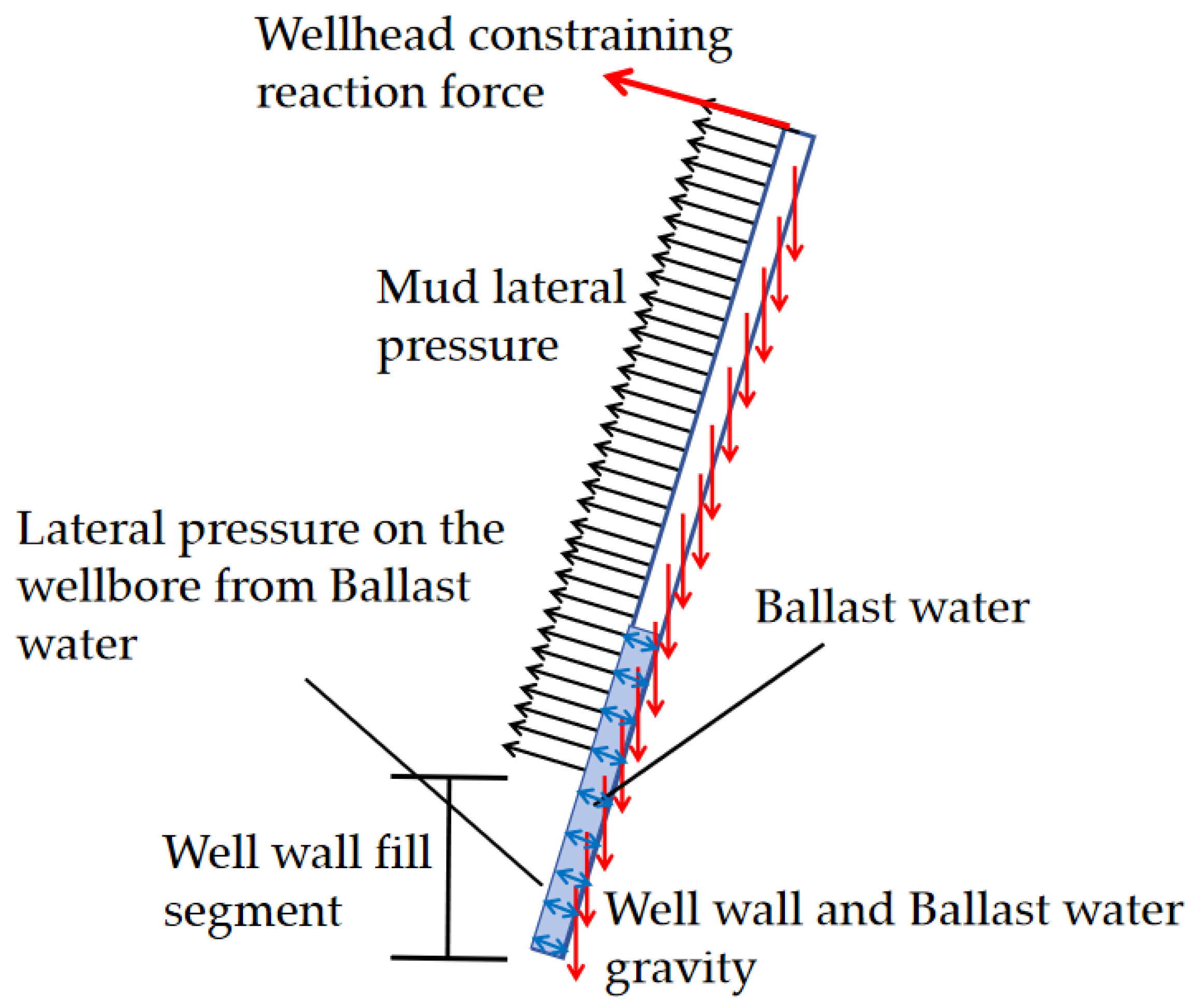

2.2. Computational Model for Assessing the Vertical Structural Integrity of Shaft Lining

- (1)

- The shaft lining is conceptualized as a slender compression member, articulated at both extremities, with the vertical support at the base simplified as an elastic foundation.

- (2)

- The vertical deflection profile of the shaft lining exhibits sinusoidal characteristics.

- (3)

- The shaft comprises n sections of wall, taking into account the effects of the thickness, material properties, and the height of the counterbalancing water of each wall section in terms of structural stability.

2.3. Calculation Formula for Vertical Structural Stability of Shaft Lining

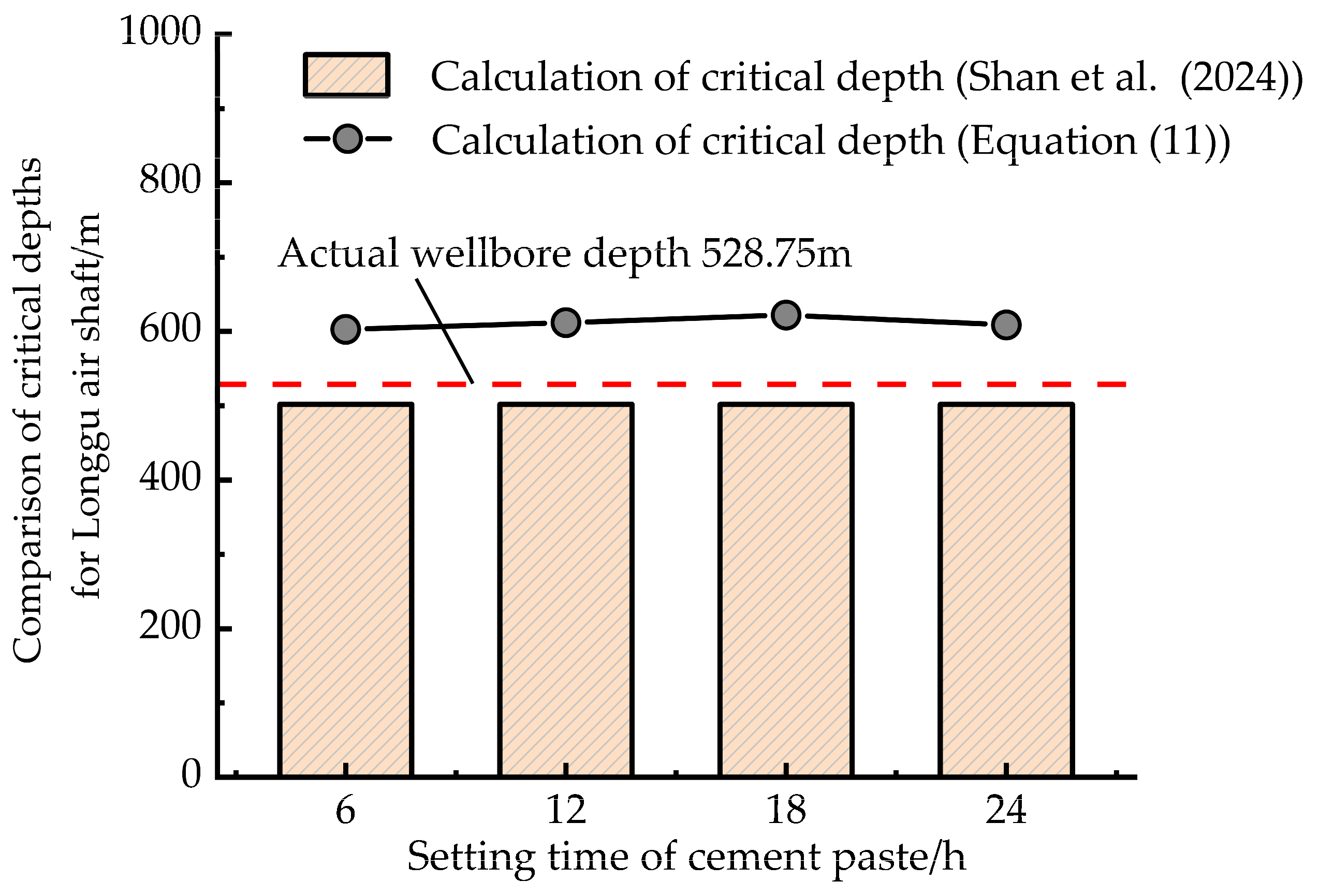

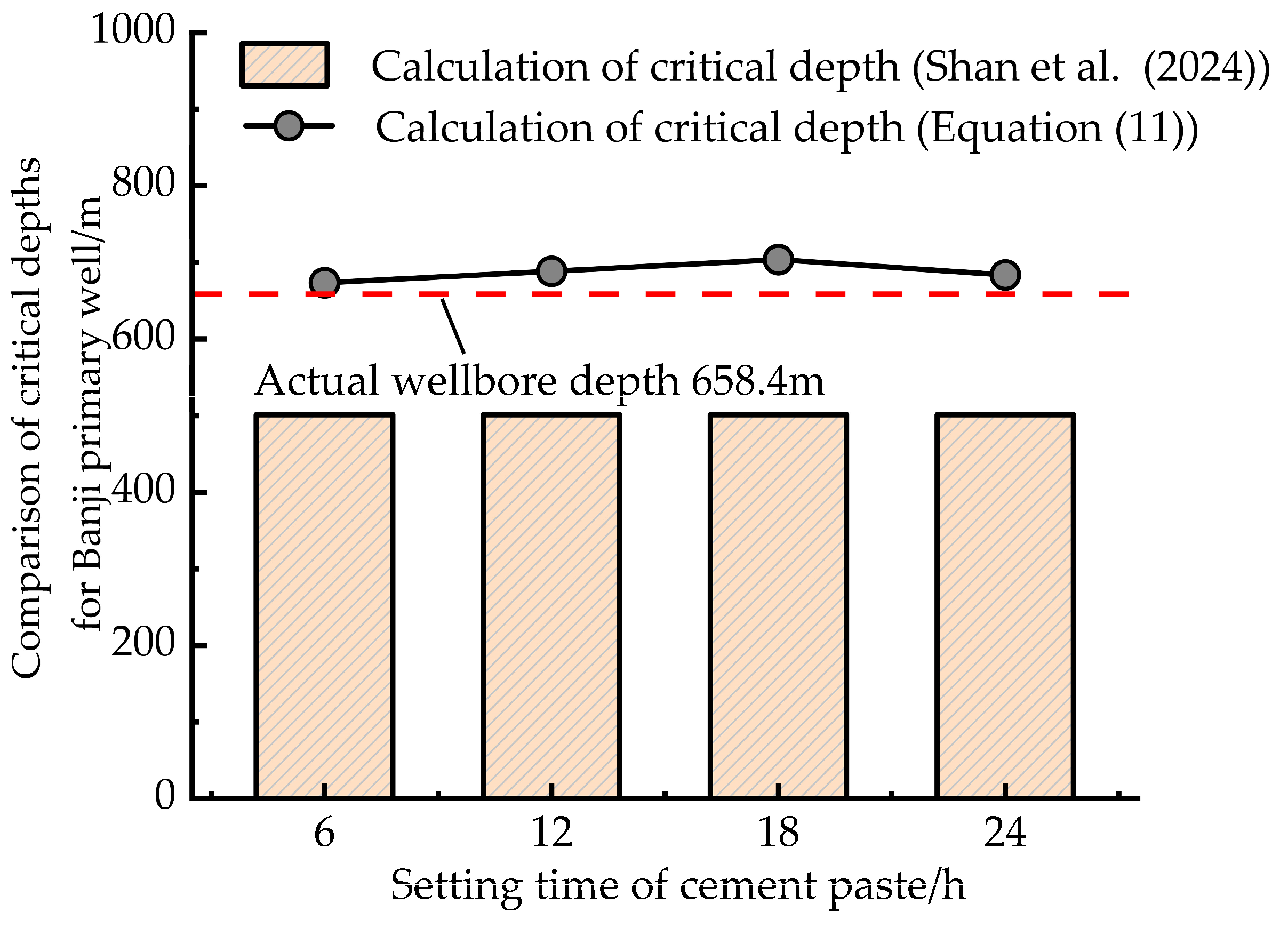

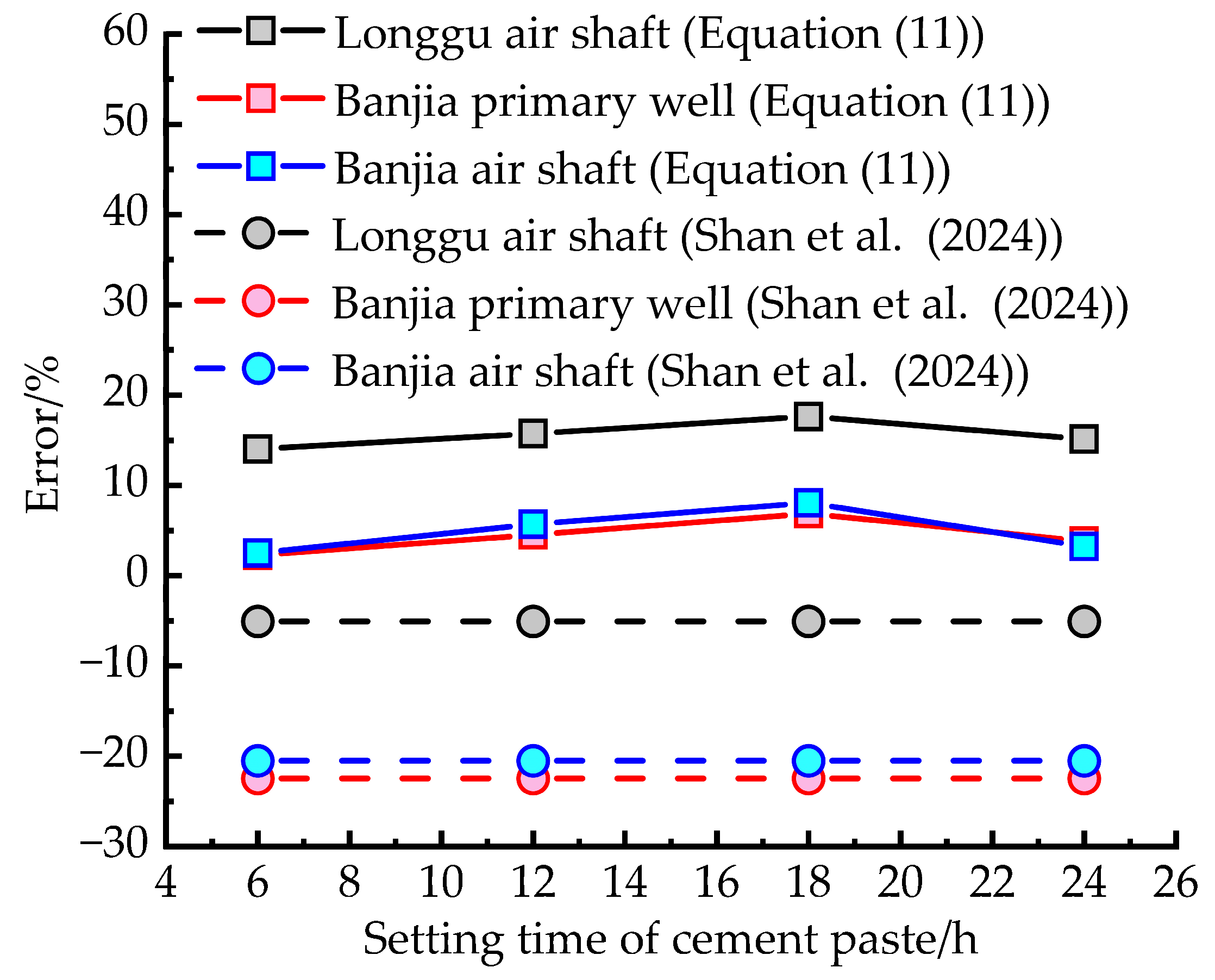

3. Results

4. The Influence of Different Factors on the Critical Depth of the Well Wall

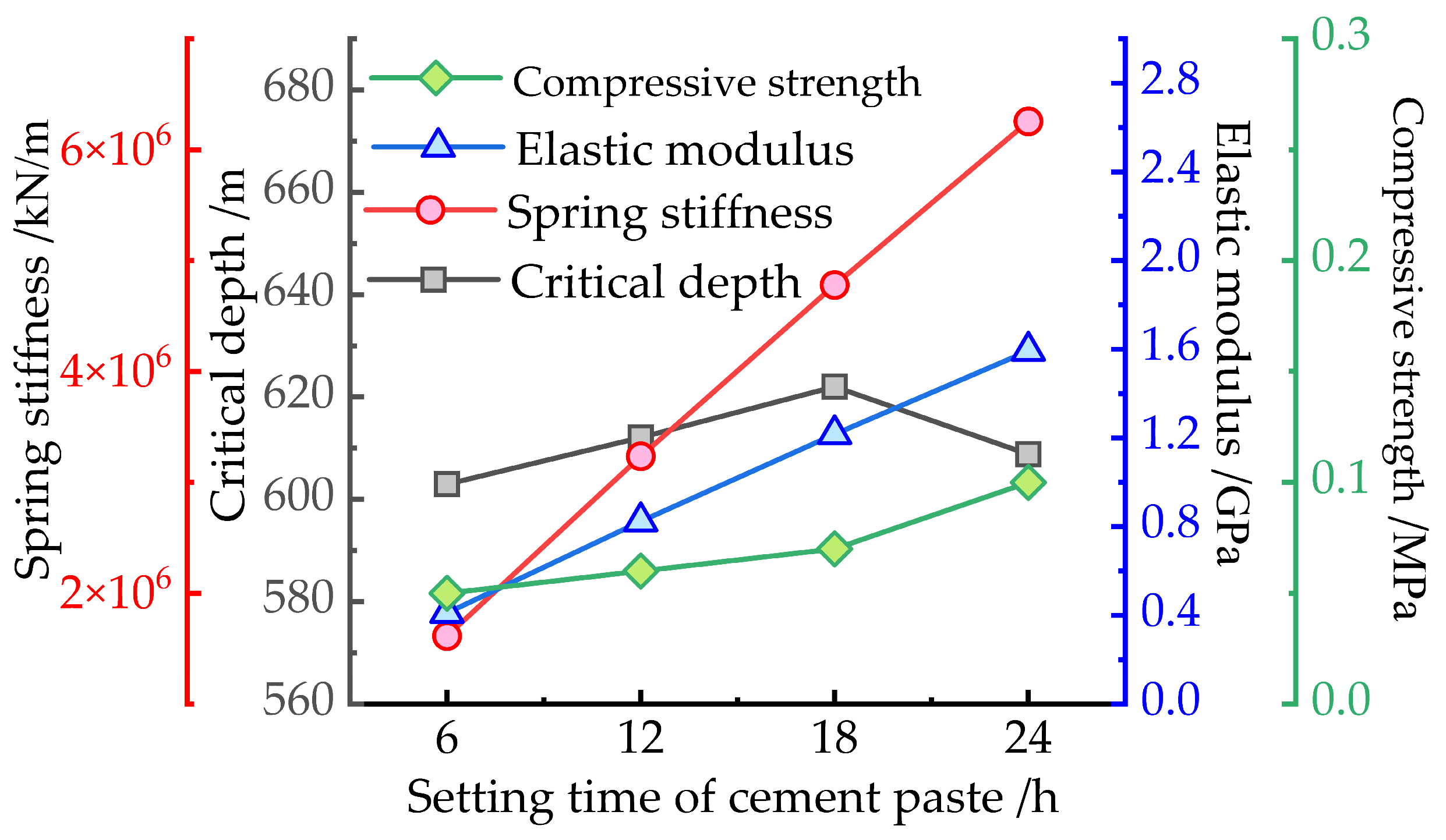

4.1. Vertical Bearing Elastic Coefficient (Kn)

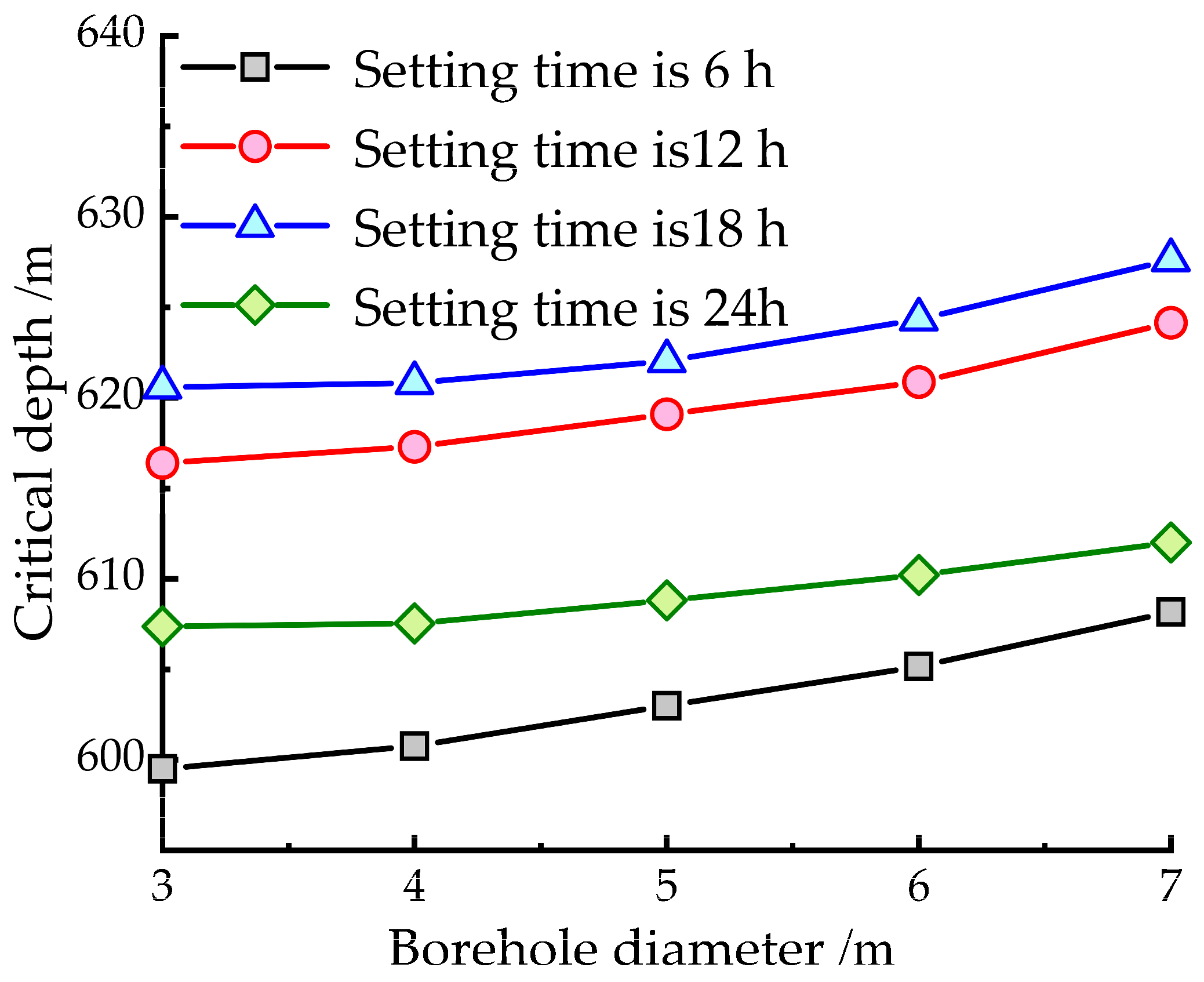

4.2. Borehole Diameter

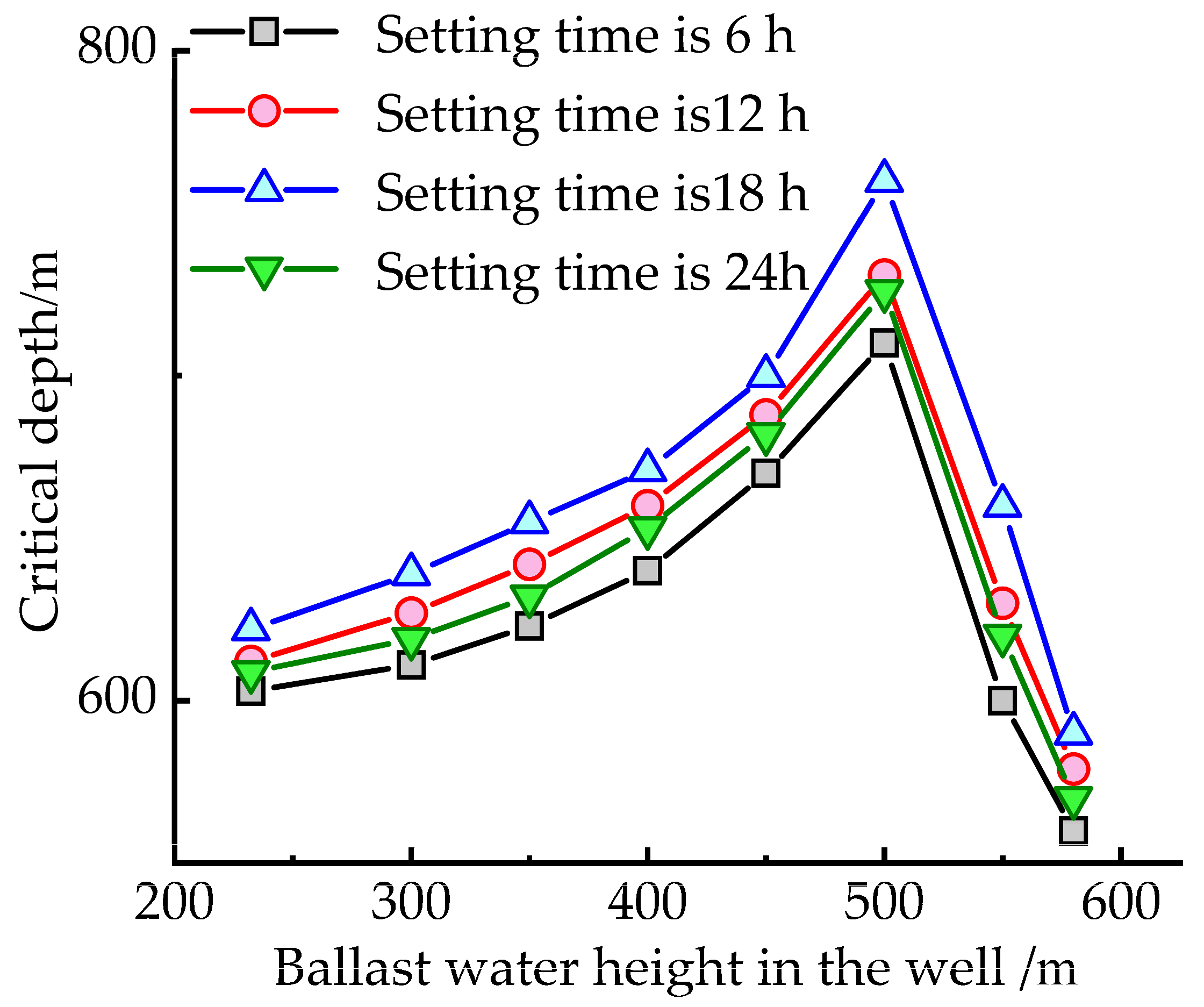

4.3. Ballast Water Height in the Well

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Although the model established in this study demonstrates good applicability in both theoretical derivation and engineering validation, it still has several limitations. The model treats the wellbore as a completely elastic medium, without considering the plastic deformation and damage accumulation effects experienced by the concrete materials during the actual stress process. Additionally, factors such as temperature variations, hydration reaction processes, and material mixing ratios—which could significantly influence the time-dependent mechanical properties of the cement slurry—are not included in the current model. Future research will further investigate the influence of different material properties on the stability of the wellbore.

- (2)

- Existing studies indicate that, under such engineering conditions, the contact state between the bottom of the wellbore and the surrounding rock is generally stable, with a low probability of occurrences such as unilateral contact, local unloading, contact failure, nonlinear stiffness-displacement responses, bond performance degradation, or interface slippage [18,19,20]. Therefore, this study does not incorporate these complex contact mechanisms into the model. Subsequent studies will combine physical model experiments with long-term field monitoring to further elucidate the variation patterns of the critical depth of the wellbore under different working conditions.

- (3)

- In establishing the analysis model for the vertical stability of the wellbore, this study simplified the upper boundary condition to a hinged support. However, in actual engineering scenarios, there may be other construction scenarios and control measures, such as using a wellhead locking device, that induce the wellbore top to approach the characteristics of a fixed support under actual working conditions. Changes in such boundary conditions will directly affect the buckling mode and critical load of the wellbore, subsequently impacting the stability assessment. Future research will further explore the influence of different upper boundary conditions on the stability of the wellbore.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.Y.; Cheng, H.; Rong, C.X.; Wang, Z.J.; Yao, Z.S.; Zhang, L.L. Strength criterion for Jurassic sandy mudstone based on energy theory. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2025, 44, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, L.Y. Conception and practice of resource utilization, energization and functionalization of coal mining subsidence areas with high groundwater level. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.F.; Peng, Y.H.; Xu, Y.X.; Meng Meng, L.Y.; Han, H.J. Development of intelligent green and efficient mining technology and equipment for thick coal seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2023, 40, 882–893. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Song, C.Y. The Latest Development of Mechanical Rock Breaking Drilling Technology and Equipment for Large Diameter Shaft in China. Mine Constr. Technol. 2022, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.B.; Yang, X.J.; Yan, X.Z.; Zhang, L.S.; Liu, Y.M. An analytic model of wellbore stability for coal drilling base on limit equilibrium method. J. China Coal Soc. 2016, 41, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Cheng, H.; Yao, Z.; Rong, C.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z. Pressure distribution and fluid migration law of gas lift reverse circulation well washing flow field in drilling sinking. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Wang, X.Y.; Yao, Z.S. The calculation model of rock breaking force of milled-tooth roller cutters for shaft sinking by drilling methods in Jurassic Strata of the Western Region. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2026, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Hu, F.Y.; Guo, L.H.; Rong, C.X.; Wang, X.Y. Experimental Study on Rock Breaking Materials of Weakly Consolidated Sandstone Drilling Method. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 43, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Xie, B.; Yao, Z.S.; Rong, C.X.; Lin, J. Wear evaluation method of drilling shaft sinking hob based on rock slag morphology and rock abrasiveness. J. China Coal Soc. 2025, 50, 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.S.; Qiao, S.X.; Wang, R.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Qi, Y.Q. Research on Simulation Backfill Test of Drilling Shaft Sinking Method in Western China. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 43, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.S.; Xu, Y.J.; Cheng, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Wang, R. Mechanical properties of a new high-strength composite shaft lining for the “one drilling and forming process” drilling method in western China. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 4365–4379. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.S.; Zhu, H.W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Zhu, J. Development and durability performance of high density cement slurry filled with drilling method for shaft sinking. Coal Eng. 2023, 48, 4365–4379. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; LI, X.Y.; Huang, J.Y. Analysis on Mine Shaft Drilling Method Applied to Mine Shaft Sinking in Western China Area—Taking the Construction of Air Inlet Shaft in Kekegai Coal Mine as an Example. Mine Constr. Technol. 2022, 43, 67–70+48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Song, C.Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, Q.; Jing, G.Y.; Sun, J.R.; Wang, Y. The design idea and method of the bit structure and drilling parameters for shaft drilling based on mechanics-structure-energy coordination model. Mine Constr. Technol. 2024, 45, 1–9+43. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Wu, Z.Z.; Wang, X.Y.; Guo, L.H.; Hu, F.Y. Optimization Preparation and Penetration Characteristics of Weakly Cemented Sandy Mudstone Rock Breaking Materials. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 45, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, B.Q. Discussion vertical structural stability of a drilled shaft in mud further. J. China Coal Soc. 2008, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, R.L.; Han, T.Y.; Jing, G.Y.; Tan, J.; Li, W.J.; Qiao, D.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Fu, X.P. Research on vertical structure stability before cementing ultra-deep wellbore by drilling method. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 49, 542–552. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X.C.; Hong, B.Q.; Yang, R.S. Study on vertical structural stability of bored shafts filled part of water. Rock Soil Mech. 2006, 1897–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.C.; Hong, B.Q.; Yang, R.S. Experiment of the axial compression of bored shafts and slipping of a shaft pan in sinking of drilling shaft lining. J. China Coal Soc. 2008, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, J.M.; Rong, C.X.; Yao, Z.S. Variable cross section shaft drilling lining’s vertical stability in thick alluvium. J. Coal Sci. Eng. 2008, 33, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, C.X.; Liu, J.M.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H. Numerical simulation on vertical stability critical height of variable cross section drilling shaft in deep alluvium. J. Coal Soc. 2007, 32, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.M.; Cheng, H.; Rong, C.X. Theoretical Study on Shaft Drilling Lining’s Vertical Stability in Floating and Dropping Phases. China Energy Environ. Prot. 2007, 11–12+43. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.S.; Li, X.W.; Cheng, H. Analysis of fluid-sold coupling mechanism of water-bearing weakly cemented surrounding rock-filling layer-drilling shaft lining in the west of China. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2008, 5, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.L.; Wang, M.S.; Nie, Q.K.; Liang, J.G. Study on mechanical behavior of shaft drilling liner during floating and dropping. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 2012, 36, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Velychkovych, A.; Mykhailiuk, V.; Andrusyak, A. Evaluation of the Adaptive Behavior of a Shell-Type Elastic Element of a Drilling Shock Absorber with Increasing External Load Amplitude. Vibration 2025, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velychkovych, A.; Mykhailiuk, V.; Andrusyak, A. Numerical Model for Studying the Properties of a New Friction Damper Developed Based on the Shell with a Helical Cut. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Wang, S.M.; Lin, Z.Y.; Zhong, M.; Chen, P.; Chen, J. Calculation Model and Verification of Shield Tunnel Segment Flotation Based on Grout Buoyancy Dissipation Characteristics. CN J. Geotech. Eng. 2026, 48, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.F.; Shi, Z.P.; Song, B.H.; Zhao, P.P. Study on Influence of Solidification Time of Grouting Material Behind Shield Tunnel Wall on Uplift of Pipe Segments. Constr. Mech. 2025, 46, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.N.; Ban, Y.T.; Ye, X.W.; Zhang, X.L.; Song, K. Research on Calculation Method of Segment Floating during Construction of Shield Tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2025, 21, 816–823. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.M.; Wang, Y.Z.; Ma, J.M. Research on the Elastic Modulus of Cement Slurry After Initial Set. J. Xi’an Univ. Arch. Tech. 2012, 44, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.Z.; Zhang, W. Analysis of soft soil with viscoelastic fractional derivative Kelvin model. Rock Soil Mech. 2007, 28, 1983–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.J.; Yao, Z.M.; Mao, F. Kelvin Creep Model of Artificial Frozen Deep Soft Rock Based on Particle Swarm Plasticity Strengthening. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2014, 10, 1602–1605+1645. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.F.; Cheng, H.; Rong, C.X.; Zhang, N.; Lin, J. Fuzzy random optimization of generalized Kelven constitutive model for creep of artificial freezing clay. Coal Geol. Explor. 2019, 47, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Xie, B.; Sun, M. Theoretical Analysis of the Vertical Stability of a Floating and Sinking Drilled Wellbore Using Vertical Elastic Supports. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031374

Zhang Z, Cheng H, Wang X, Xie B, Sun M. Theoretical Analysis of the Vertical Stability of a Floating and Sinking Drilled Wellbore Using Vertical Elastic Supports. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031374

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhiwei, Hua Cheng, Xiaoyun Wang, Bao Xie, and Mingrui Sun. 2026. "Theoretical Analysis of the Vertical Stability of a Floating and Sinking Drilled Wellbore Using Vertical Elastic Supports" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031374

APA StyleZhang, Z., Cheng, H., Wang, X., Xie, B., & Sun, M. (2026). Theoretical Analysis of the Vertical Stability of a Floating and Sinking Drilled Wellbore Using Vertical Elastic Supports. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031374