1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of global trade and logistics, the flow of goods has increased significantly, with shipping handling over 90% of global cargo [

1]. However, this expansion has raised maritime safety concerns, particularly as ships navigate busy and complex routes, leading to frequent accidents. According to data from the International Maritime Organization (IMO) through the Global Integrated Shipping Information System, ship collisions account for 20% of all maritime accidents, causing significant economic losses, casualties, and environmental damage each year [

2]. Therefore, ensuring the safety of shipping operations is critical to economic performance, as well as the protection of lives and the environment.

The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs), published by the IMO, provide the fundamental legal framework for ship collision avoidance. These rules define the principles that ships must follow during navigation to reduce the risk of collisions. However, some provisions of these rules are relatively vague in terms of specific operational interpretations, especially in the complex and dynamic real-world maritime environment, where captains or crew members need to make decisions based on experience and real-time judgment. Statistics show that approximately 80% of ship collision accidents are caused by human error in operation [

3]. The rapid growth of shipping and the increasing complexity of maritime traffic have made the traditional model, controlled by a single ship operator, inadequate for meeting the growing demands of maritime safety and transportation. Thus, providing collision avoidance decision support or enabling autonomous decision-making for ships is crucial.

To better understand the development of current intelligent collision avoidance methods, it is necessary to review the evolution of theories and methods for ship collision avoidance. In the 1950s and 1960s, foreign scholars began to systematically investigate the fundamental theory of ship collision avoidance. Using geometric and mathematical methods, they quantitatively analyzed ship motion characteristics and proposed key concepts such as the distance to the closest point of approach (DCPA), the time to the closest point of approach (TCPA), and the ship domain, thereby laying the foundation for subsequent research. Later, Goodwin [

4] further refined the classification of ship relative orientations in the 1970s, and Davis [

5] introduced the concept of the dynamic ship domain in the 1980s, which promoted the development of collision avoidance decision-making and risk assessment methods. Under the guidance of COLREGs, Reference [

6] constructed a collision avoidance knowledge base using expert system technology based on ship collision avoidance principles and quantitative research results, and designed and partially implemented an automatic collision avoidance expert system to assist pilots in making real-time collision avoidance decisions.

Building on these foundations, many studies have explored the use of deterministic methods in collision avoidance. The Dijkstra algorithm [

7] is a non-heuristic search strategy that relies solely on current distance information, without considering the direction or position of the target node. While it performs well in simple path planning, its efficiency is relatively low in complex environments, as it explores all paths until all nodes are processed. The global multi-directional A* algorithm proposed in [

8] improves ship path planning in wind farm waters by employing a multi-directional search strategy, which better adapts to complex waters. However, the fixed grid method has limited path optimization and collision avoidance performance in dynamic obstacle environments, making it difficult to plan the optimal collision-free path in real time. Zhang Jinfen et al. [

9] proposed an adaptive step-size Rapidly exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithm that incorporates a ship dynamic model and step-size prediction for path planning. The step size is adaptively adjusted according to the obstacle distribution and combined with a motion model and virtual obstacles, thereby enhancing collision avoidance performance in complex environments. Ref. [

10] presented a motion-planning method that combines model predictive control and the artificial potential field method. By constructing a new ship domain and closed-interval potential field functions, the method avoids falling into local optima and uses the Nomoto model to generate trajectories consistent with ship kinematic characteristics. Ref. [

11] integrated membrane computing, Genetic Algorithms (GA) [

12], and the artificial potential field method, and proposed a membrane evolutionary artificial potential field approach for ship collision avoidance decision-making. However, such methods usually rely on pre-acquired environmental information and have limited responsiveness to dynamic changes. In particular, their performance is often unsatisfactory when dealing with moving obstacles, which increases the risk of collision. Consequently, deterministic methods in ship collision avoidance suffer from certain limitations, such as constrained turning angles and inadequate handling of the motion parameters of dynamic obstacles, making it difficult to obtain globally optimal collision avoidance solutions.

To overcome the shortcomings of deterministic methods in dynamic environments and global optimization, researchers have turned to heuristic intelligent algorithms. With the development of GA, neural networks [

13], Particle Swarm optimization (PSO) [

14], and other intelligent algorithms, a wave of research applying heuristic algorithms to ship collision avoidance decision-making has emerged worldwide. Reference [

15] proposed a cooperative collision avoidance approach based on an improved GA. In addition to traditional crossover and mutation operations, this method introduces new genetic operators, such as retention, deletion, and replacement, which allow more flexible adjustment of waypoints, headings, and speeds, thereby achieving efficient collision avoidance. Liu Hao [

16] proposed a global path-planning algorithm for ships based on an environmental model. The algorithm constructs a navigation connectivity graph using a probabilistic graph and incorporates multi-objective optimization of wave impact, navigation energy consumption, and path length into the particle swarm algorithm. The path is smoothly optimized using a decoupled ship model. Validation in the Zhoushan waters shows that the improved algorithm increases navigation comfort by 18.49% to 24.75% and reduces energy consumption by 0.52% to 0.56%, outperforming traditional algorithms. A hybrid beetle antennae search-simulated annealing (BAS-SA) algorithm is proposed to enhance global optimization capability and avoid entrapment in local optima for two-ship and multi-ship collision avoidance problems [

17]. To enhance the search capability of collision avoidance algorithms for unmanned surface vehicles, Reference [

18] proposed an improved Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). In static unknown environments, the algorithm improves real-time performance through local environmental modeling; in known dynamic environments, it handles dynamic obstacles by incorporating a speed model and COLREGs. In addition, the pseudo-random proportional rule was improved, and a wolf-pack allocation strategy together with a max–min ant system was used to update pheromones, thereby accelerating convergence and avoiding local optima.

Based on the above analysis, deterministic methods have certain limitations in optimizing ship collision avoidance decisions and generally perform poorly in dynamic obstacle environments. By contrast, heuristic algorithms can be more easily integrated with geometric collision avoidance theory for ships, allowing a more accurate description of the ship’s motion state and a more flexible representation of collision avoidance trajectories. Therefore, heuristic algorithms are more suitable for application to ship collision avoidance decision-making. Motivated by the need to improve the efficiency and quality of ship collision avoidance decisions, this study selects the African Vultures Optimization Algorithm (AVOA) as the main research focus. AVOA is a swarm intelligence optimization algorithm inspired by the foraging behavior of African vultures. Vultures are known for their excellent scavenging ability and keen sense of smell, which enable them to detect carcasses at long distances and forage efficiently. Since its introduction by Abdollahzadeh et al. in 2021 [

19], AVOA has attracted widespread attention and achieved promising results in various application domains. Compared with other optimization algorithms, AVOA exhibits strong robustness when dealing with complex optimization problems and can adapt to different problems and environments. Its unique modeling of hunting behavior and position-updating mechanisms allows it to converge rapidly when searching for optimal solutions. Chen Yitao et al. [

20] improved AVOA by introducing Tent chaotic mapping and a time-varying mechanism, which enhanced the algorithm’s global exploration capability, expanded the search range, and reduced the influence of local extrema on performance. Qi Dezhong et al. [

21] proposed an improved AVOA to optimize the parameters of an extreme learning machine prediction model for ship motion conditions. In that work, Circle chaotic mapping was adopted in population initialization to increase population diversity, and an adaptive operator was added to adjust the guiding effect of the two types of vultures on other individuals, thereby improving the convergence speed and solution quality of the algorithm.

In summary, this paper proposes an innovative ship collision avoidance decision-making method to address the limitations of current approaches. The proposed method fully exploits the strong robustness of AVOA and incorporates SA into the AVOA framework to perform local refined search. Through the synergy between the two algorithms, the proposed model enhances its adaptability to ship collision avoidance tasks and maximizes the potential of the overall framework. The main contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) A novel AVOA-SA hybrid optimization algorithm is designed, in which Tent mapping and SA-based local perturbations are introduced to enhance global exploration and avoid premature convergence. (2) A COLREG-oriented multi-objective collision avoidance formulation is established, explicitly incorporating navigational safety, COLREG compliance, turning amplitude, and path economy. (3) Extensive simulations of multi-ship encounter scenarios demonstrate that the proposed method can generate collision avoidance trajectories that are both safe and economical, and that it outperforms the standard AVOA and other benchmark algorithms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the research methodology, including ship collision risk assessment, ship collision avoidance objective functions, and the principles of the relevant models.

Section 3 evaluates the proposed framework through simulation experiments and analysis.

Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions and contributions of this work, points out its limitations, and discusses possible directions for future research.

2. Methods

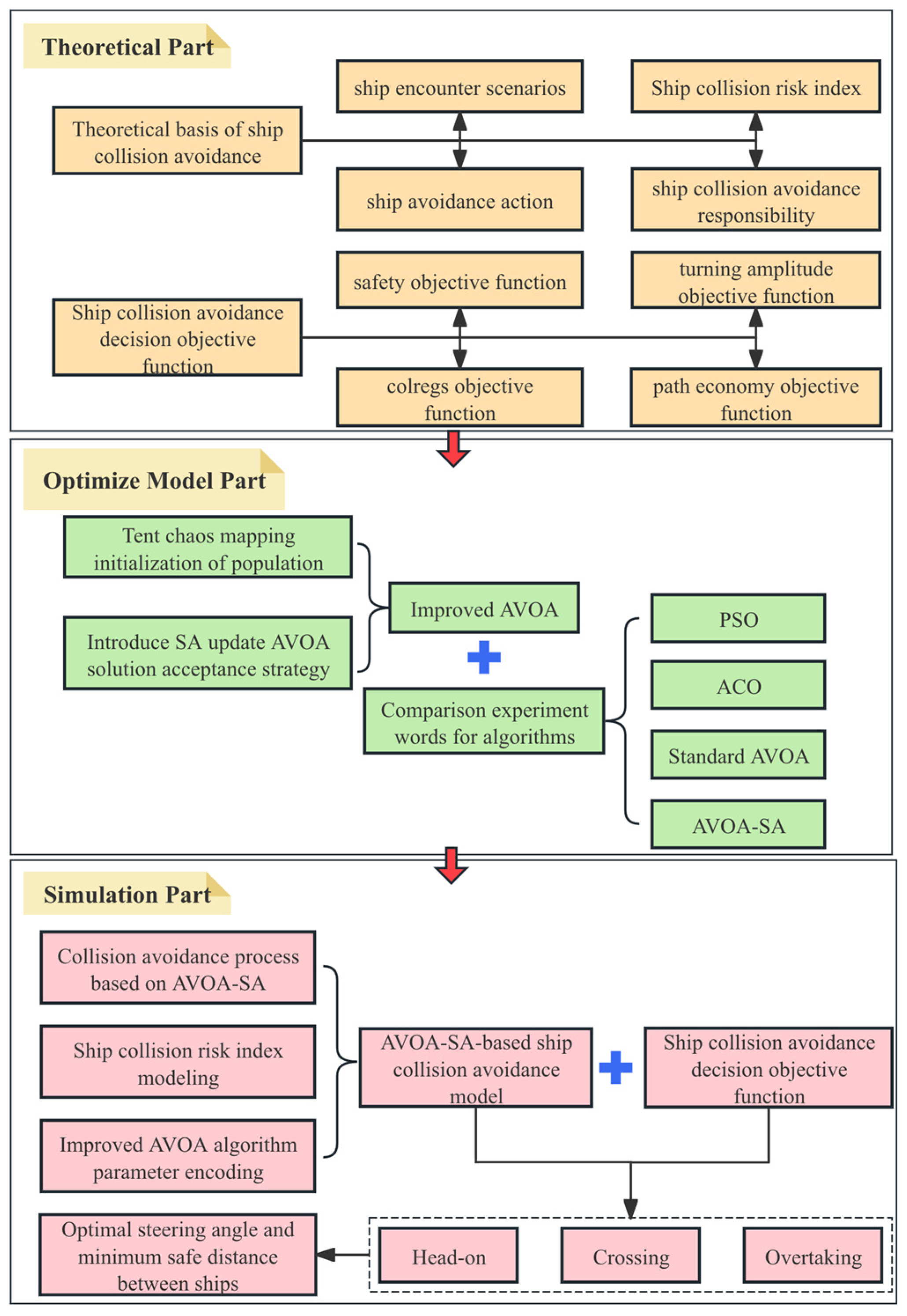

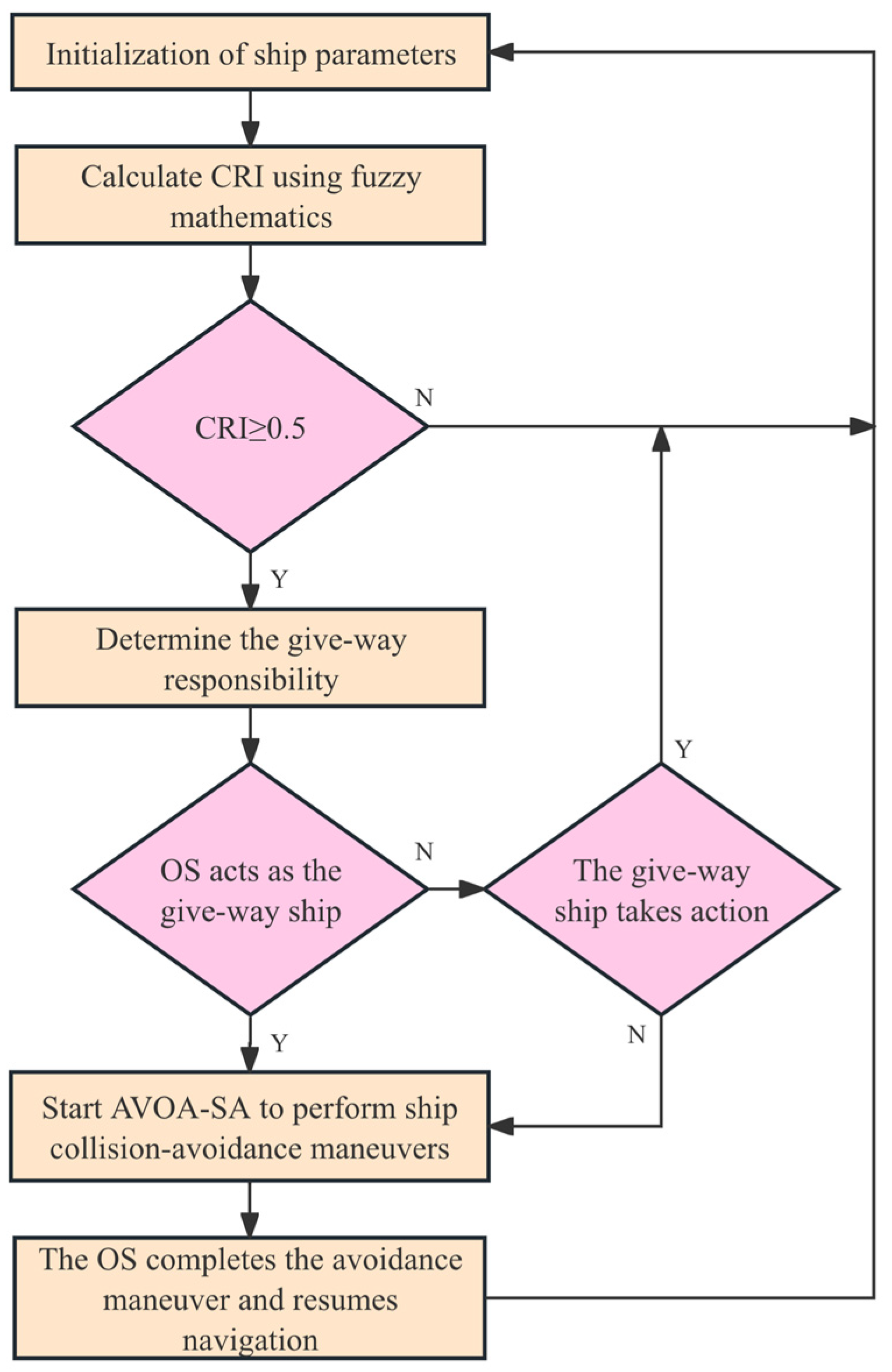

Ship collision avoidance is a complex process that involves the ship’s motion, COLREGs, and related decision-making mechanisms. This study, based on the improved AVOA, proposes a new ship collision avoidance decision-making framework. This section introduces the research methods and overall framework, as shown in

Figure 1. To ensure the reliability of the data and the validity of the conclusions, the framework consists of three main modules: first, the ship collision risk is introduced through the basic theory of ship collision avoidance, and the corresponding ship collision avoidance objective function is constructed; second, the AVOA is improved and its performance is compared with several other algorithms; finally, simulation experiments are conducted under three typical encounter situations: head-on, crossing, and overtaking.

2.1. Theoretical Basis of Ship Collision Avoidance

In ship collision avoidance decision-making, accurately determining the encounter situation is crucial, as it directly affects the appropriateness of avoidance actions. According to the COLREGs, different rules apply depending on whether vessels are in sight of one another or operating under restricted visibility conditions. Rules 11–18 regulate the responsibilities of vessels in sight of one another, clearly defining stand-on and give-way vessels in various encounter situations, whereas Rule 19 applies to restricted visibility and emphasizes safe speed and early action without explicitly assigning right-of-way.

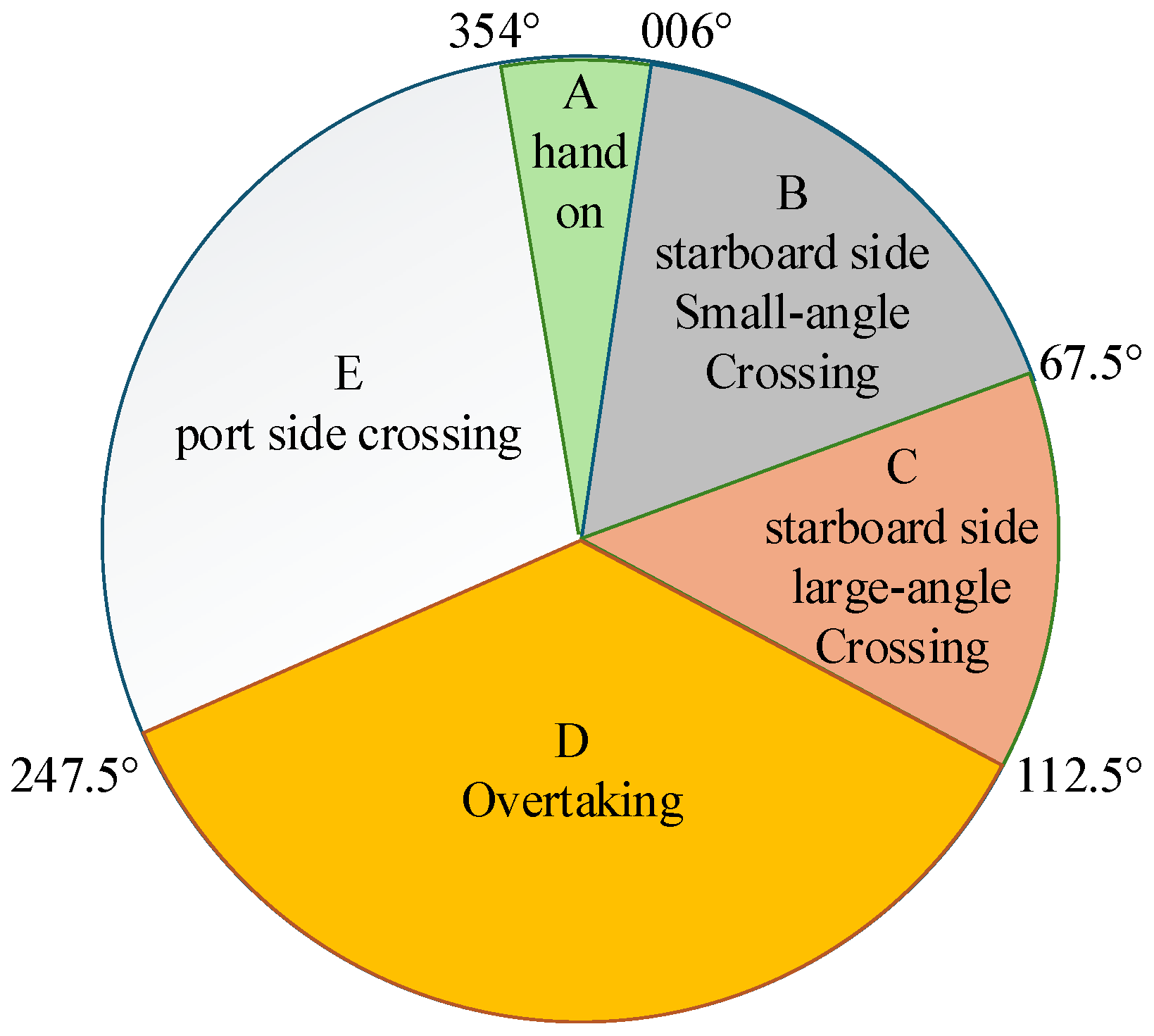

In this study, ship collision avoidance decision-making is investigated under good visibility conditions in open waters, where vessels are assumed to be in sight of one another. Therefore, the collision avoidance strategy and decision-making model are developed in accordance with Rules 11–18 of COLREGs. Under this assumption, ship encounter situations are classified into three main types: head-on, crossing, and overtaking situations [

22]. For each encounter situation, ships should take corresponding avoidance measures based on the specific circumstances to ensure navigational safety. The ship encounter situations are classified as follows and are illustrated in

Figure 2. (1) Head-on: The target ship (TS) approaches the own ship (OS) from sector A (354°–006°). Both vessels alter course to starboard and pass port-to-port. (2) Starboard small-angle crossing: TS approaches from sector B (006°–67.5°). TS maintains its course, while OS, as the give-way vessel, alters course to starboard and passes safely astern of TS. (3) Starboard large-angle crossing: TS approaches from sector C (67.5°–112.5°). OS, acting as the give-way vessel, alters course to port to avoid collision. (4) Overtaking: TS overtakes OS from sector D (112.5°–247.5°). OS, as the stand-on vessel, maintains its course and speed. (5) Port-side crossing: TS approaches from sector E (247.5°–354°). OS, as the stand-on vessel, maintains its course and speed.

In the decision-making process, the Collision Risk Index (CRI) model is used to quantify the collision risk between ships and assess the urgency of avoidance actions. The CRI value ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no collision risk and 1 indicates a certain collision. When the CRI value reaches or exceeds a certain threshold, the ship must take immediate avoidance measures. By calculating key parameters such as DCPA and TCPA, the severity of the collision risk can be evaluated. In this study, unacceptable maneuvering deviations are controlled through the proposed collision risk index together with a multi-criteria collision avoidance formulation that integrates navigational safety, COLREG compliance, turning amplitude, and path economy. The analysis is limited to ship–ship collision avoidance in open waters under good visibility conditions, and scenarios involving fixed obstacles or restricted waters are not considered.

Based on the above analysis, this paper constructs a ship CRI model, using the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method to assess collision risk, and calculates the final collision risk using membership functions. The model considers five factors: , , the distance between ships (), relative bearing (), and the ship speed ratio (), to support the ship in making rational collision avoidance decisions.

- (1)

Dangerous membership function of

where

represents the value of the ship’s safety domain, the safe passing distance is

, and under normal conditions

.

- (2)

Dangerous membership function of

where

represents the latest time for the ship to apply the helm, and

represents the time required for the two ships to reach

DCPA from an initial encounter distance of 12 nautical miles in the simulation. This distance is adopted as an engineering-oriented setting for collision risk assessment and

TCPA calculation, rather than a fixed

DCPA threshold specified by COLREGs.

is the relative speed between OS and TS.

- (3)

Dangerous membership function of

where the latest avoidance distance is

, and the distance at which the avoidance maneuver is applied is

, The visibility is

, and the navigation water area condition factor

and human factor

are set to 1 under normal conditions. The latest maneuver distance is

, which is typically taken as about 12 times the ship’s length according to navigational practice and existing studies [

23].

represents the radius of the ship’s maneuvering boundary.

- (4)

Dangerous membership function of

When the relative bearing between TS and OS changes, the collision risk will also change accordingly. The formula is as follows:

- (5)

Dangerous member ship function of

where

is the speed of OS,

is the speed of TS, and

is the ship speed ratio. Generally,

is taken as the limit for the speed ratio [

24].

Based on the above five influencing factors, a ship

CRI model is constructed [

25]:

The weight coefficients of the five influencing factors range from 0 to 1. Based on the reference literature their values are determined as follows:

,

,

,

,

[

26], and they satisfy the following formula:

2.2. Ship Collision Avoidance Objective Function

In AVOA, the fitness of each vulture individual reflects the quality of the solution: the higher the fitness, the better the solution. The behavior of each individual is guided by its current fitness and the best individual in order to search for the optimal solution. The fitness function is designed on the basis of the objective function, and different optimization problems correspond to different objective functions.

The objective of this study is to minimize the value of the objective function; therefore, the fitness function is designed such that a smaller objective function value corresponds to a larger fitness value [

27]. The fitness function is defined as follows:

where

is the designed overall objective function, which takes into account four aspects: navigational safety, COLREGs, turning amplitude, and path economy, so as to ensure the comprehensiveness and rationality of the ship collision avoidance strategy.

2.2.1. Navigational Safety Objective Function

Navigational safety refers to a ship’s ability to navigate safely in a given water area in accordance with relevant rules, technical standards, and environmental conditions, thereby avoiding the risk of accidents. To ensure that the ship does not collide or enter dangerous areas, safety is evaluated by comparing the minimum distance between ships with the radius of the safety domain.

where

x denotes an individual in the vulture population, which corresponds to a collision avoidance path. Equation (15) represents the safety of the entire path.

measures the minimum Euclidean distance between OS and the most dangerous TS at the path point

, and is used to evaluate the safety risk of the current path.

represents the radius of the ship’s safety domain.

2.2.2. COLREG-Based Objective Function

The COLREGs, formulated by the IMO, constitute a set of rules governing collision avoidance between vessels at sea. In this paper, the rules are quantified and transformed into an objective function. At path point

i, OS evaluates the collision risk with the most dangerous TS. For the leg between path points

i and

i + 1, it then checks whether the course change complies with COLREGs. By summing the degree of compliance over all legs, the overall COLREG compliance of the entire path is obtained [

28].

Assume that the course of OS is

, the course of TS is

, the course difference is

, the relative bearing of OS as seen from TS is

, and the relative bearing of TS as seen from OS is

. The encounter situations and corresponding maneuvering requirements are summarized in

Table 1.

Based on the above COLREG-compliant encounter classification and maneuvering rules, each candidate collision avoidance path is evaluated to determine its overall compliance with the COLREGs, and the corresponding objective function is formulated as follows:

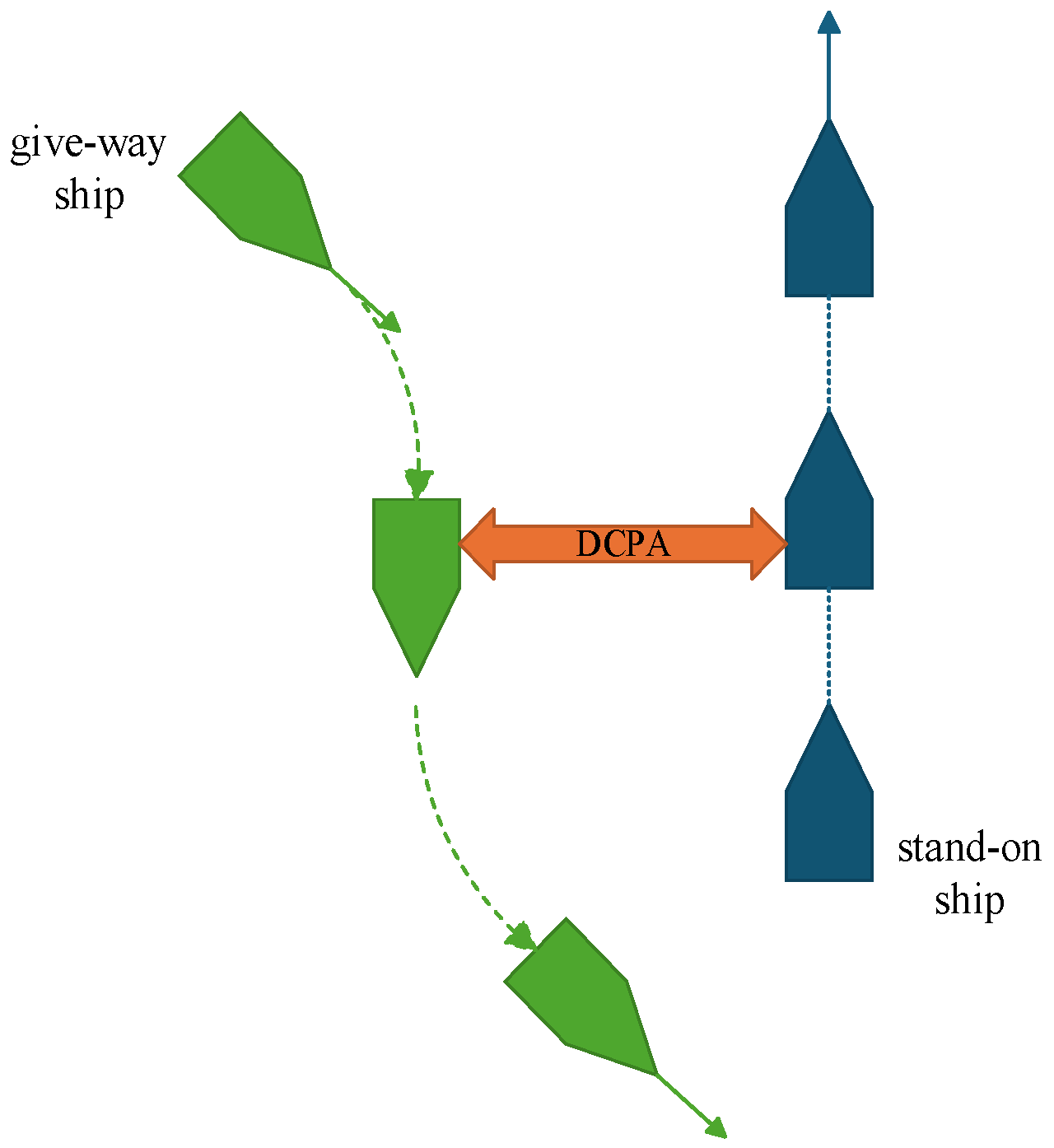

2.2.3. Turning Amplitude Objective Function

Considering the COLREGs requirement that the give-way vessel take early and substantial action, the magnitude of the course alteration is set to be no less than 15°, and starboard alterations are generally given priority during the collision avoidance process. Accordingly, in the collision avoidance optimization of AVOA-SA, starboard course changes are adopted as the preferred maneuver, as shown in

Figure 3.

Moreover, since frequent small heading changes may reduce navigational stability, an angle-based evaluation function is designed to penalize course alterations and indirectly reflect their frequency. The corresponding objective function is defined as follows:

where

is the difference between the ship’s heading before and after the maneuver.

2.2.4. Path Efficiency Objective Function

Economy is one of the key factors in the ship collision avoidance process. The shorter the path, the lower the energy consumption and the better the economy. Conversely, an excessively long avoidance path not only increases energy consumption but also raises the risk of collision. Therefore, the objective function is primarily designed to achieve economic goals by optimizing the total path length.

where

denotes the distance between two adjacent path points

i and

i + 1; the shorter the path length, the better the objective function value.

By linearly weighting and summing the above objective functions, with the sum of the weight coefficients equal to 1, the final collision avoidance objective function is obtained:

where

,

,

, and

are the weight coefficients corresponding to each objective function. With reference to the relevant literature [

29], the weight coefficients in this paper are set as:

= 0.3,

= 0.3,

= 0.2, and

= 0.2.

2.3. Ship Collision Avoidance Decision-Making Based on AVOA-SA

Vultures typically forage in groups, and once food is found, multiple vultures quickly gather and compete for it, exhibiting both competition and cooperation. The vulture group optimizes the foraging process through information sharing, accelerating resource discovery and utilization. In AVOA, each vulture represents a solution to the optimization problem. Let the dimension of the optimization space be

Q, and the population size be

N; then the position of the

i-th vulture in the

Q-dimensional space is represented as:

where

represents the position of the

i-th vulture in the

q-th dimension.

The AVOA consists of two phases: exploration and exploitation. The transition between these phases depends on the hunger rate

of the vultures. When the vultures are less hungry, they tend to fly farther in search of food, whereas when they are hungry, they fly shorter distances. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where

is the hunger rate of the vultures. When |

| ≥ 1, AVOA is in the exploration phase; when |

| < 1, it is in the exploitation phase, during which the vultures forage around the current optimal solution. The parameter

is a predefined coefficient before the optimization process and reflects the balance between exploration and exploitation during optimization.

denotes the current iteration number,

M is the maximum number of iterations,

z is a random number in the range [−1, 1],

h is a random control parameter used to adjust the step size and search direction of the vultures. It is uniformly distributed in the range [−2, 2] to enhance search diversity and ensure a proper balance between exploration and exploitation.

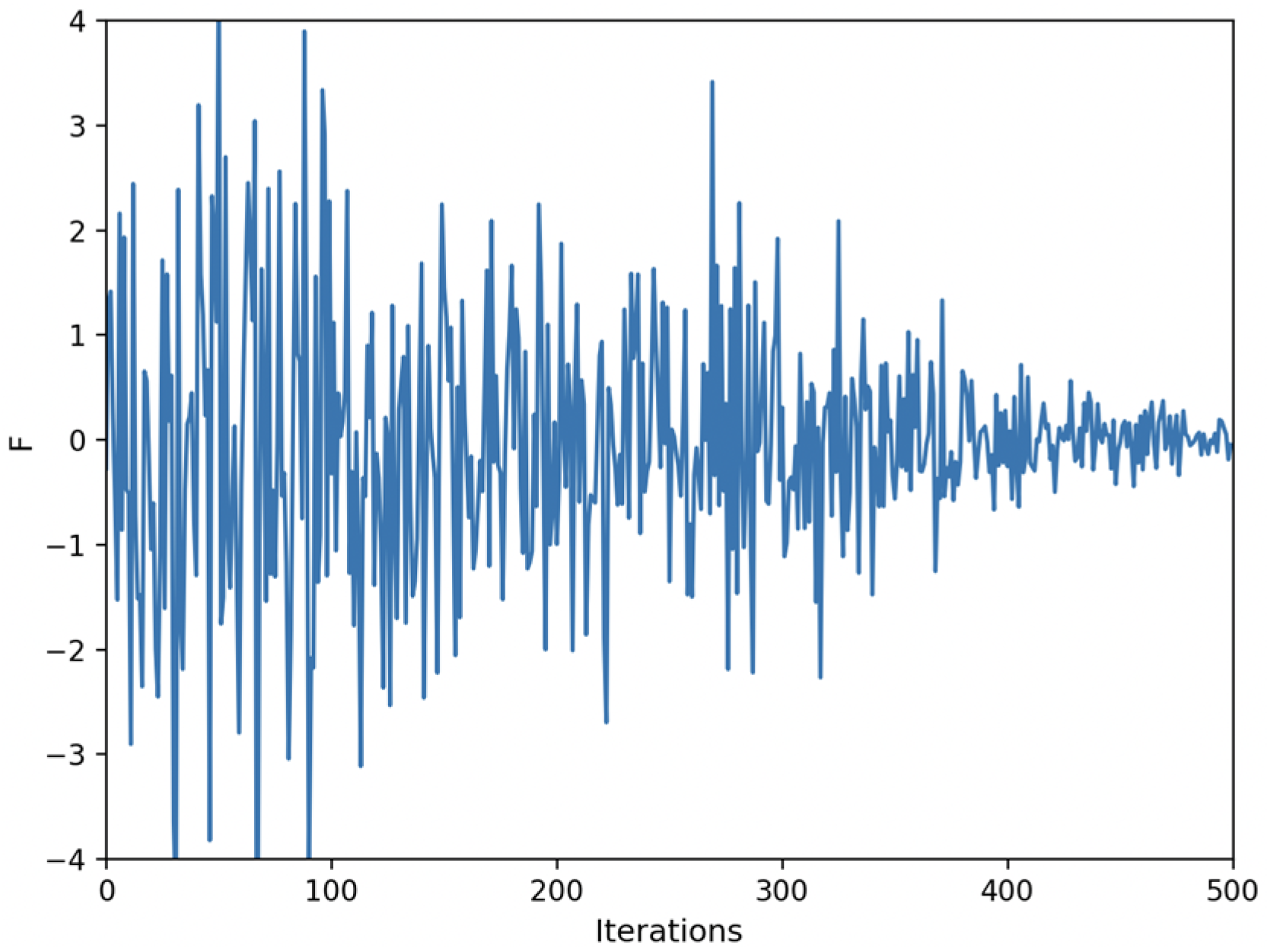

is a random number in the range [0, 1]. The hunger rate defined in Equation (25) is calculated for each individual vulture and controls its transition between exploration and exploitation, independent of the group assignment. The variation in the vultures’ hunger rate is shown in

Figure 4.

2.3.1. The Specific Procedure of AVOA

- (1)

Determination of the global best and second-best vulture positions

After initialization, vultures are grouped by fitness: the best individual forms group 1, the second-best forms group 2, and all remaining individuals form group 3. The best and second-best individuals serve as search leaders, and Equation (26) specifies which leader each individual moves toward.

in the formula,

denotes the leader position selected for the

i-th vulture from the two best vultures, where

and

represent the best and second-best vultures, respectively.

+

= 1, and both are random numbers in the range [0, 1].

represents the fitness value of the

i-th vulture in the first and second groups (leader groups), and

n represents the total number of the first and second groups of vultures.

- (2)

Exploration Phase

In the exploration phase, the vultures’ flight behavior represents gliding for a long time, and the flight distance is relatively large. At this point, the vultures’ hunger degree is relatively low (|

| ≥ 1), so they can perform extensive exploration. In AVOA, the parameter

determines which type of vulture the vulture will explore. The position information of the vulture in the exploration phase is updated according to the following formula:

in the formula,

is a random number between [0, 1], and

is the preset exploration parameter.

is the vulture’s position vector in the next iteration,

is the hunger rate of the vulture in the current iteration,

X is a constant. Both

and

are random numbers between [0, 1].

lb and

ub are the lower and upper bounds for the optimization process.

- (3)

Exploitation Phase

When 0.5 ≤ || < 1, the algorithm enters the mid-term exploitation phase, using a parameter control between 0 and 1 to guide the vulture to perform a rotational flight or encirclement strategy. When || < 0.5, the vulture’s hunger increases, and its behavior becomes more aggressive, leading to the convergence of multiple vultures and aggressive fighting.

2.3.2. The Improvement of AVOA

- (1)

Tent chaotic mapping initial population

In AVOA, the population is initialized by randomly placing individuals. Although this ensures diversity, it may lead to some regions in the solution space being over-concentrated. This results in poor solution quality and the initial values being scattered, causing some individuals to be concentrated in local areas, while others are spread across the entire solution space.

To address this issue, this paper adopts the Tent chaotic mapping [

30] method to initialize the population in the solution space, avoiding excessive concentration, and thus exploring the solution space more comprehensively. The specific expression for initializing the population is:

in the formula,

denotes the position of the

i-th individual;

and

are its upper and lower bounds; and

is its chaotic parameter, initialized with a random value in [0, 1]. The trajectory of the Tent chaotic map is shown in

Figure 5.

- (2)

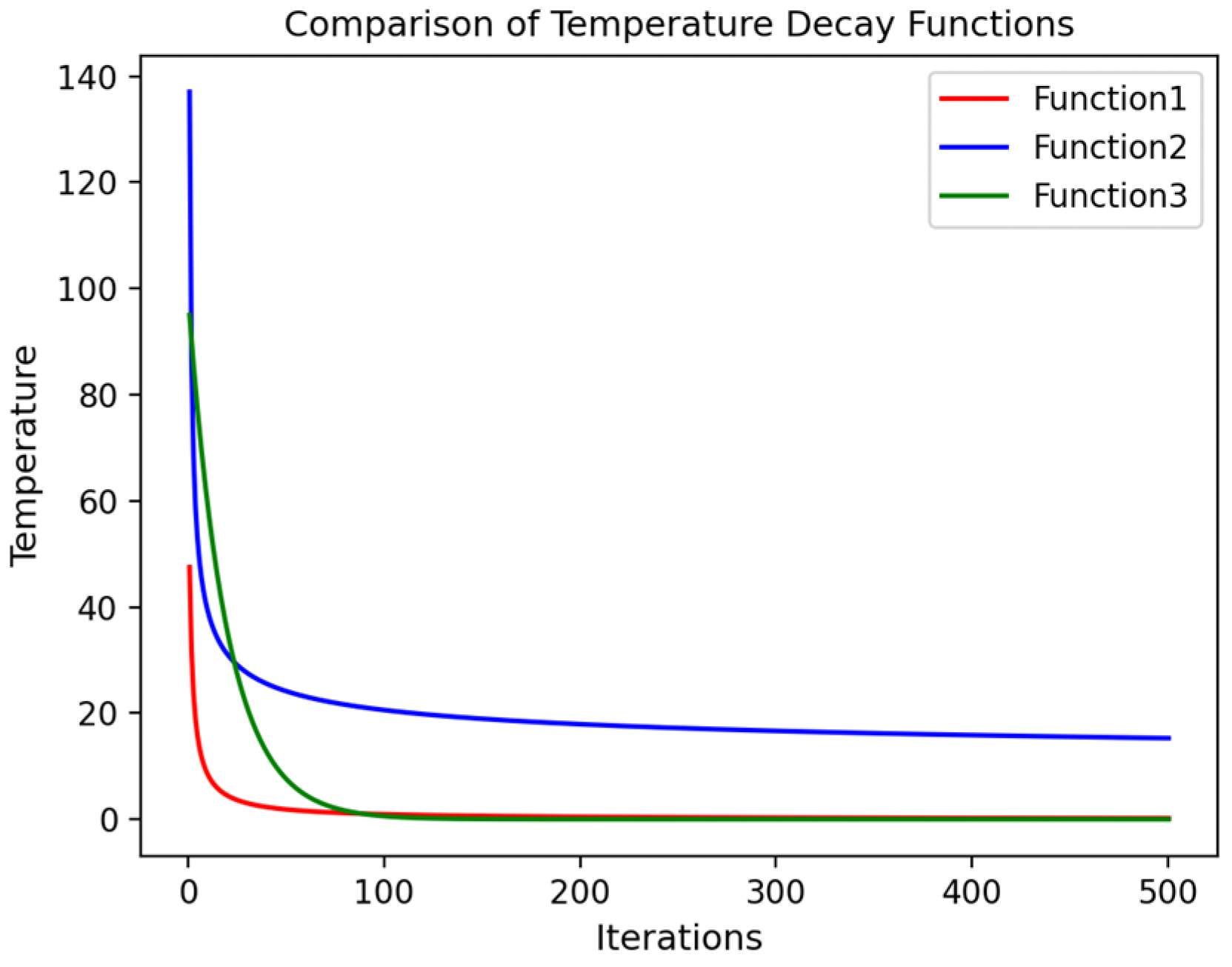

Define the temperature decay function to control the temperature change

The core idea of SA is to initially allow relatively large-scale search, avoiding local optima, and later reduce the search scope to fine-tune and achieve global optimal solutions. Different decay functions have different cooling rates and search characteristics, so selecting the appropriate cooling function is crucial for the algorithm’s performance. The commonly used three temperature decay functions are as follows:

where

is the initial temperature,

is the temperature at the

k-th iteration,

k is the iteration number, and

is the decay constant. Typically,

ranges from 0.8 to 0.99. The cooling curves for the three decay functions are shown in

Figure 6. The first function is given by Equation (32), the second by Equation (33), and the third by Equation (34).

In AVOA, during the early stage, a wide search space is preferred to find the optimal solution, with the goal of maximizing the exploration. As the iterations increase, the algorithm reduces the disturbance, and more focus is placed on local searches to refine the solution. The temperature decay function simulates the gradual change in the cooling rate, which slows down as the search space reaches a stable state.

Figure 6 shows that the change trend of the third cooling function matches the AVOA’s requirement for a gradual decrease in cooling rate, so this paper selects the function represented by Equation (34) to optimize the search process.

- (3)

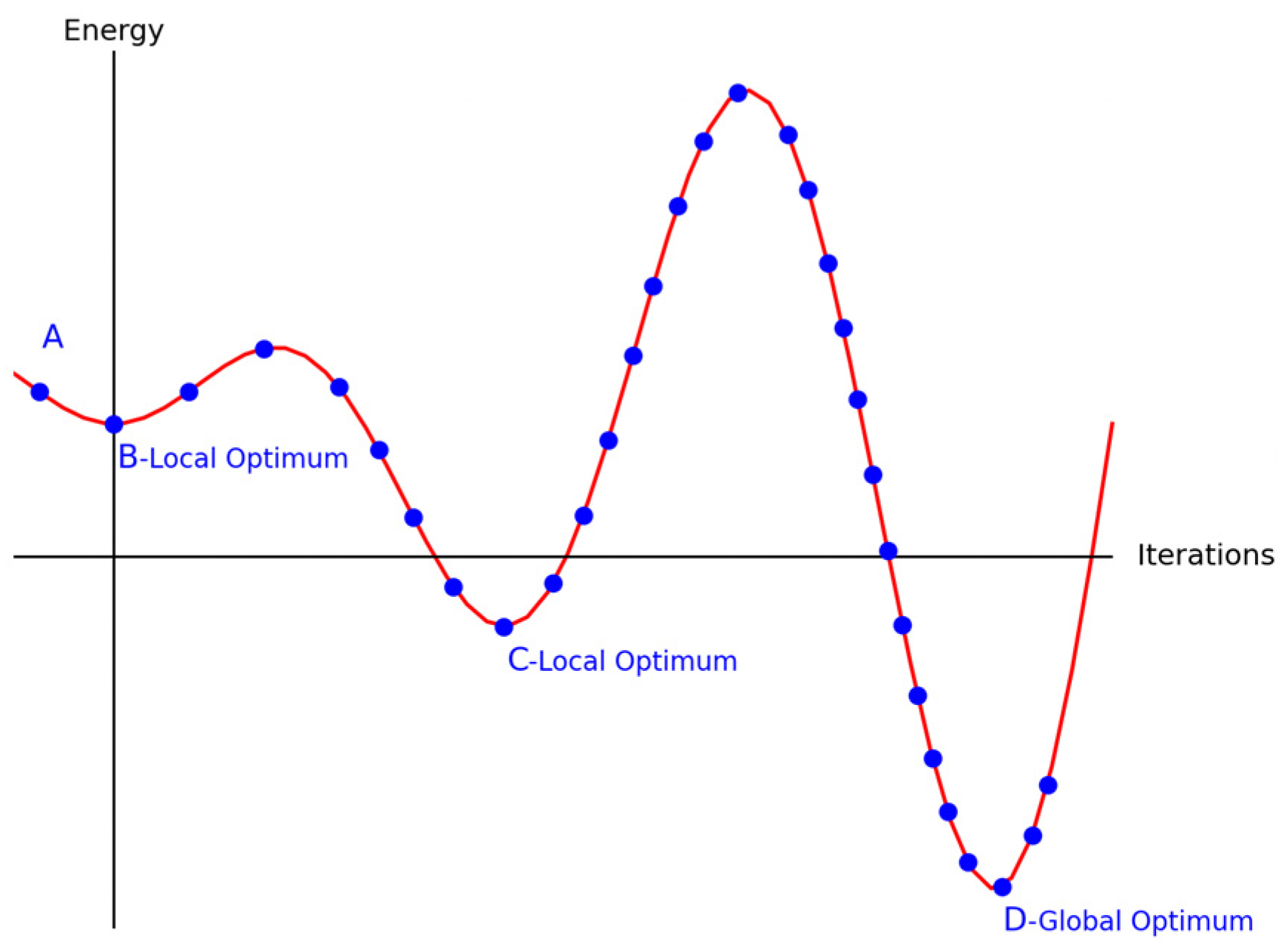

Metropolis algorithm

The Metropolis algorithmis the core of SA and provides a probabilistic mechanism for escaping local optima. Proposed by Metropolis et al. [

31], it introduces importance sampling, allowing a new state to be accepted with a certain probability instead of relying solely on deterministic rules. Starting from an initial state A, repeated updates produce a new state B. If the energy of B is lower than that of A, then B is directly accepted. If the energy of B is higher, then it is accepted with a probability determined by the energy difference and the current temperature. In this way, the algorithm can escape local optima with a certain probability and, under appropriate conditions, converge to a global optimum. The Metropolis acceptance criterion is given by:

in the formula,

represents the probability of transitioning from state

to state

,

and

represent the energy values of states

and

, respectively.

k is the Boltzmann constant, and

T is the current temperature.

Figure 7 shows the energy change in the SA process.

Therefore, the Metropolis criterion is crucial, as it enables the SA to accept suboptimal solutions with a certain probability, effectively avoiding local optima and successfully finding the global optimum.

2.3.3. The Core Idea of AVOA-SA

Under the visibility conditions in open waters, ships often encounter scenarios where two vessels meet and urgently need to make fast and accurate collision avoidance decisions. However, as the maritime navigation environment becomes increasingly complex, how to achieve efficient real-time decision-making during two-ship encounters, while improving response speed and decision accuracy in multi-ship encounters, becomes a key challenge for algorithm improvement. Standard AVOA typically determines the next movement direction based only on the current position in high-dimensional space, which can lead to the algorithm becoming trapped in local optima, thus affecting its optimization performance in complex situations. To address this issue, this study combines the annealing process of SA with AVOA, enabling AVOA to accept worse solutions under certain conditions, avoiding local optima and improving its adaptability and decision accuracy in complex collision avoidance scenarios.

The improved algorithm adopts the following strategies: (1) Temperature adjustment: The temperature gradually decreases in each iteration, affecting the vulture’s movement strategy. In the early stages, higher temperatures make the vulture’s search behavior more random, allowing the acceptance of worse solutions. As the temperature decreases, the vulture gradually tends to accept better solutions, refining the search process. (2) Position update: The vulture’s position update is a continuous process, adjusted based on the difference between the current solution and the global best solution. As the iteration progresses, the vulture’s search step gradually decreases, eventually converging to the optimal solution. Experimental studies show that when a vulture finds a new position that is better than its current one, it moves to the new position. If the new position is worse, then the vulture decides whether to continue moving based on a certain probability, influenced by the global best and individual best solutions.

The novel hybrid optimization algorithm incorporating SA is developed. In this study, the SA mechanism is employed as an optimization strategy to enhance global search capability. It is used to improve solution exploration and avoid premature convergence. On the basis of retaining the core advantages of AVOA, it introduces a probabilistic jump mechanism that effectively alleviates the tendency of the algorithm to become trapped in local optima. By adjusting the temperature parameter, a dynamic balance between global search and local search is achieved, thereby significantly improving the efficiency and performance in solving complex optimization problems. The procedure for applying AVOA-SA to ship collision avoidance is shown in

Figure 8.

3. Results

This section first conducts a performance comparison between the improved AVOA-SA and other intelligent algorithms, and then applies AVOA-SA to simulate and verify ship collision avoidance in three-ship and four-ship encounter scenarios.

3.1. Algorithm Comparison

This section does not aim to directly evaluate ship collision avoidance performance, but to provide a supplementary assessment of the general optimization capability and robustness of the proposed AVOA-SA. Since ship collision avoidance can be formulated as a complex nonlinear optimization problem, standard benchmark functions are widely adopted to verify the convergence behavior and global search ability of optimization algorithms. The practical effectiveness of the proposed method in ship collision avoidance scenarios is mainly validated in

Section 3.2 through dedicated simulation experiments.

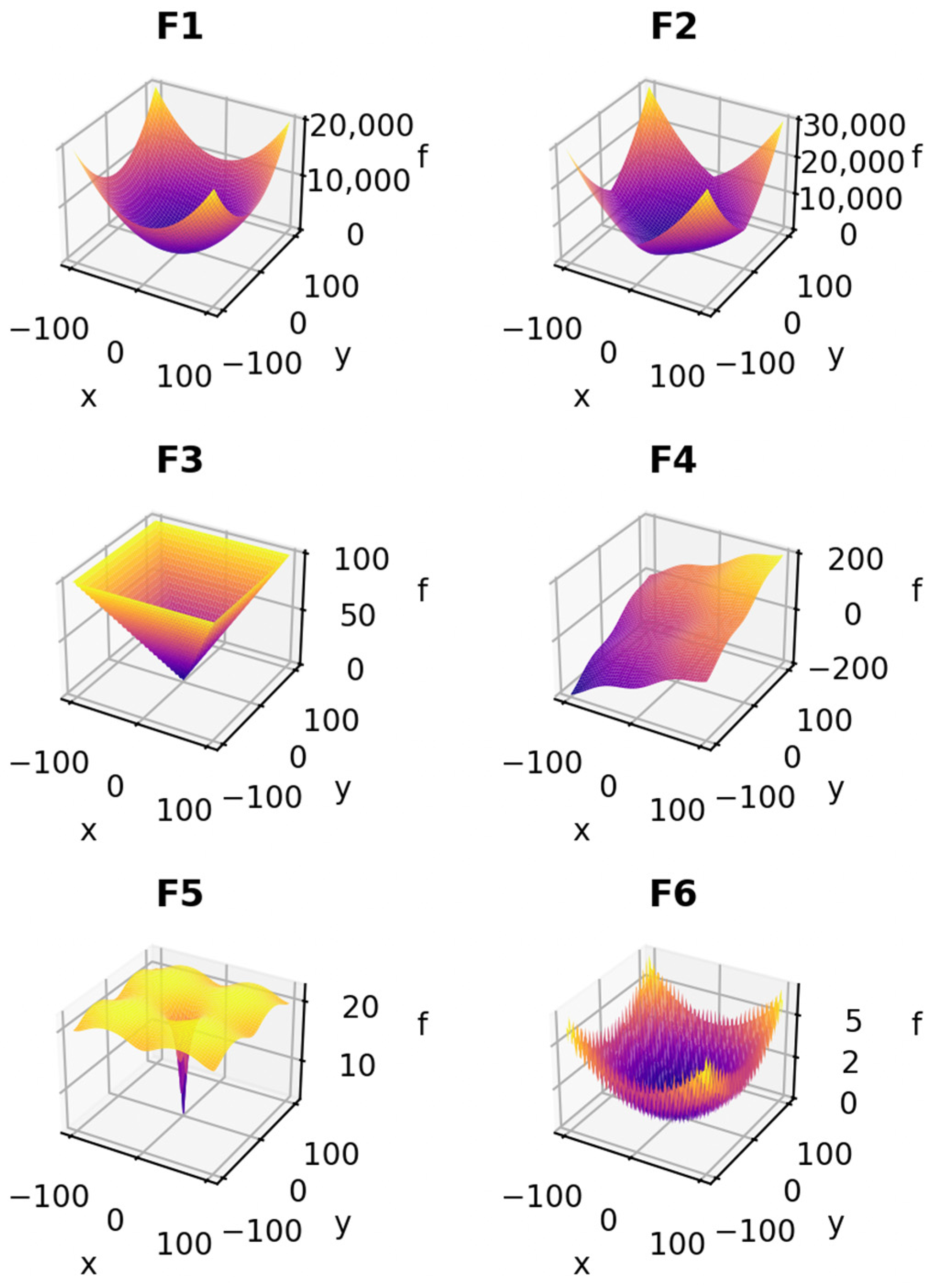

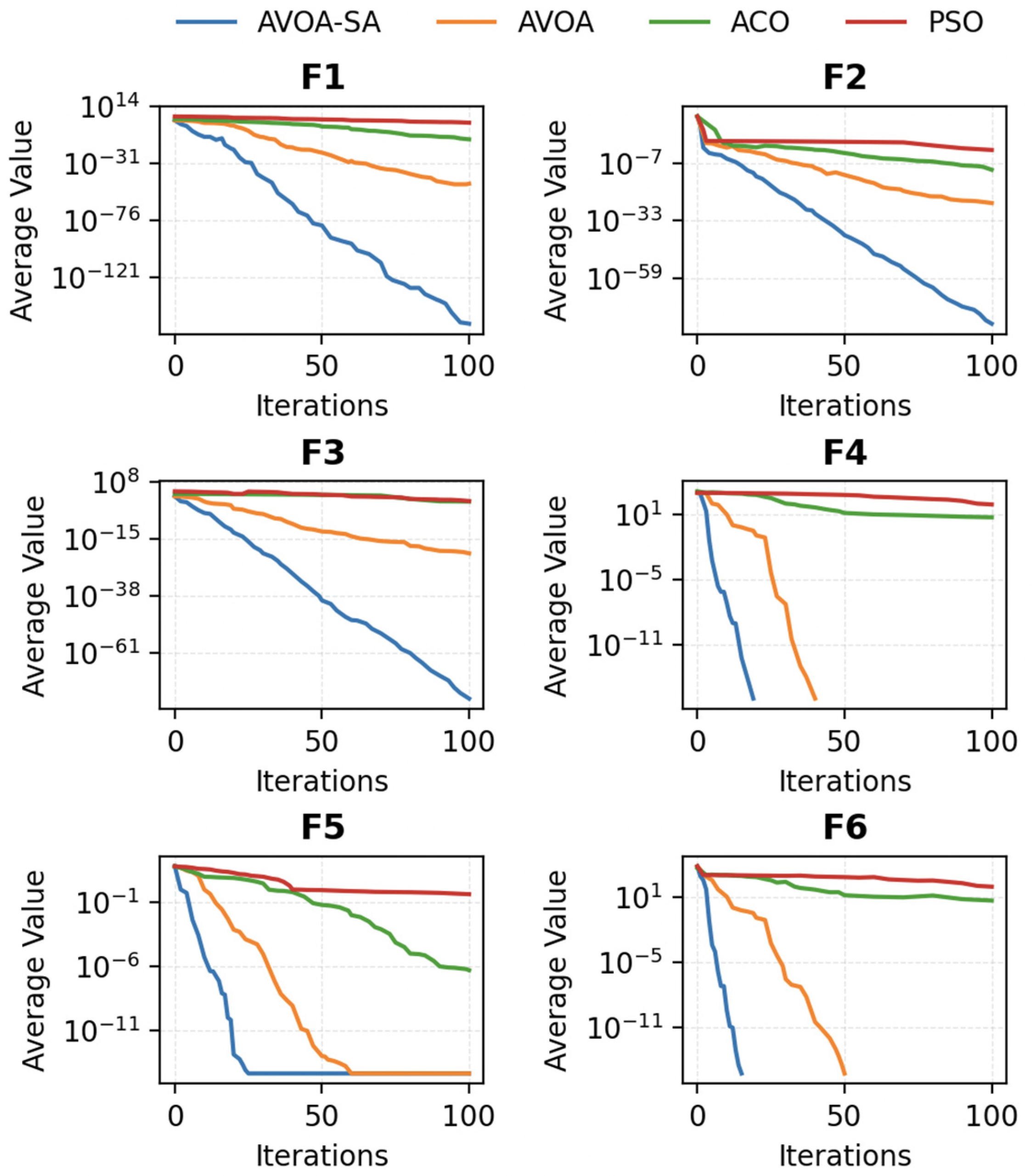

To verify the optimization performance of AVOA-SA, algorithm comparison experiments are carried out. The performance of AVOA-SA is compared with that of AVOA and other optimization algorithms using benchmark test functions. Six classical benchmark functions [

32] are selected: unimodal functions F1–F3 are used to test convergence speed, and multimodal functions F4–F6 are used to evaluate global exploration ability and the capability of escaping local optima. In this section, the dimension of all benchmark functions is set to 30, which is a commonly adopted setting in optimization algorithm benchmarking to evaluate performance in moderate- to high-dimensional search spaces. The domain is [−100, 100], and the global optimum is 0. The specific functional forms are given in

Table 2.

The corresponding function landscapes are shown in

Figure 9.

To illustrate the convergence behavior of the different algorithms, convergence curves are used for comparison. To ensure fairness, the population size is set to N = 30, the maximum number of iterations to T = 100, the dimension of the fitness function to 30, and each algorithm is independently run 50 times. The figures show the average convergence curves of the four algorithms on the six benchmark functions. If a curve tends to become stable as the number of iterations increases, then it indicates that the algorithm has successfully converged to the optimal solution. The average and standard deviation values, together with the convergence curves, indicate that the proposed AVOA-SA exhibits stable performance under the adopted parameter settings.

Although benchmark functions cannot fully represent real ship encounter scenarios, the results in this section provide complementary evidence of the optimization performance of the proposed algorithm, which supports the application-oriented simulations presented in the following section rather than replacing them.

3.1.1. Convergence Curve Comparison

As shown in

Figure 10, AVOA-SA performs best on unimodal functions F1–F3, showing the fastest convergence speed and achieving the closest to the optimal solution. The method’s search efficiency is improved by avoiding local optima and stabilizing the convergence speed. In comparison, ACO and PSO converge more slowly and tend to stall in the later stages. AVOA’s search efficiency is better than AVOA-SA and other algorithms, with minimal stalling. For multimodal function F4, AVOA-SA, and AVOA perform best during the early stages, with convergence speed clearly better than PSO and ACO. In F5 and F6, AVOA-SA demonstrates faster convergence to the optimal solution and better search capability than PSO and ACO, thus exhibiting superior search performance.

3.1.2. Convergence Rate Comparison

According to

Table 3, AVOA-SA demonstrates significantly superior convergence accuracy and stability compared with AVOA on the unimodal benchmark functions F1–F3. For function F1, the average value and standard deviation of AVOA-SA are reported as zero, indicating that the optimization error has been reduced to a numerically negligible level. For functions F2 and F3, the corresponding results of AVOA-SA are reduced by more than 50 orders of magnitude compared with AVOA, PSO, and ACO, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid strategy. For multimodal functions F4 and F5, AVOA-SA and AVOA maintain good stability and global exploration capabilities. Regarding F6, AVOA-SA successfully avoids local optima, and compared to AVOA, the average value and standard deviation are improved by at least two orders of magnitude. In terms of stability, AVOA-SA generally has a lower standard deviation than the other algorithms, demonstrating better stability.

3.2. Ship Collision Avoidance Simulation Analysis

In this study, various multi-ship encounter scenarios are simulated on the VSC platform under an open sea environment, where external factors such as wind, waves, and currents are neglected. In practical navigation under good visibility conditions, collision avoidance is mainly achieved through course alteration in accordance with COLREGs, while engine reversal is generally regarded as an emergency maneuver. Therefore, in the simulations, TS is assumed to act as the stand-on vessel and maintain its course and speed, whereas OS serves as the give-way vessel and executes collision avoidance maneuvers. This modeling assumption allows the decision-making process to focus on typical, COLREG-compliant encounter scenarios. In the simulation figures, the y-axis points to true north and the x-axis to due east.

To simulate shipborne perception and decision support functions within the collision avoidance process, RADAR and ARPA are employed for target detection and tracking. RADAR provides real-time information on the relative distance and bearing of surrounding target ships, while ARPA processes this information to track target motions and estimate key encounter parameters such as DCPA and TCPA. These parameters are then used for collision risk assessment and encounter situation identification, serving as inputs to the proposed AVOA-SA decision-making framework.

In the simulations, both OS and TS are assumed to operate under fully loaded conditions, and their parameters are taken from the ship data listed in

Table 4. Ship displacement and speed are implicitly incorporated through the ship domain constraints and relative motion parameters used in the collision risk assessment, with fixed displacement values adopted throughout the simulations. The collision risk threshold is set to 0.5: when CRI ≥ 0.5, OS plans an avoidance route using AVOA-SA; otherwise, it continues to sail along its original route. The population size is set to 50 and the maximum number of iterations to 100, with the remaining algorithm parameters given in

Table 5.

3.2.1. Three-Ship Collision Avoidance Simulation

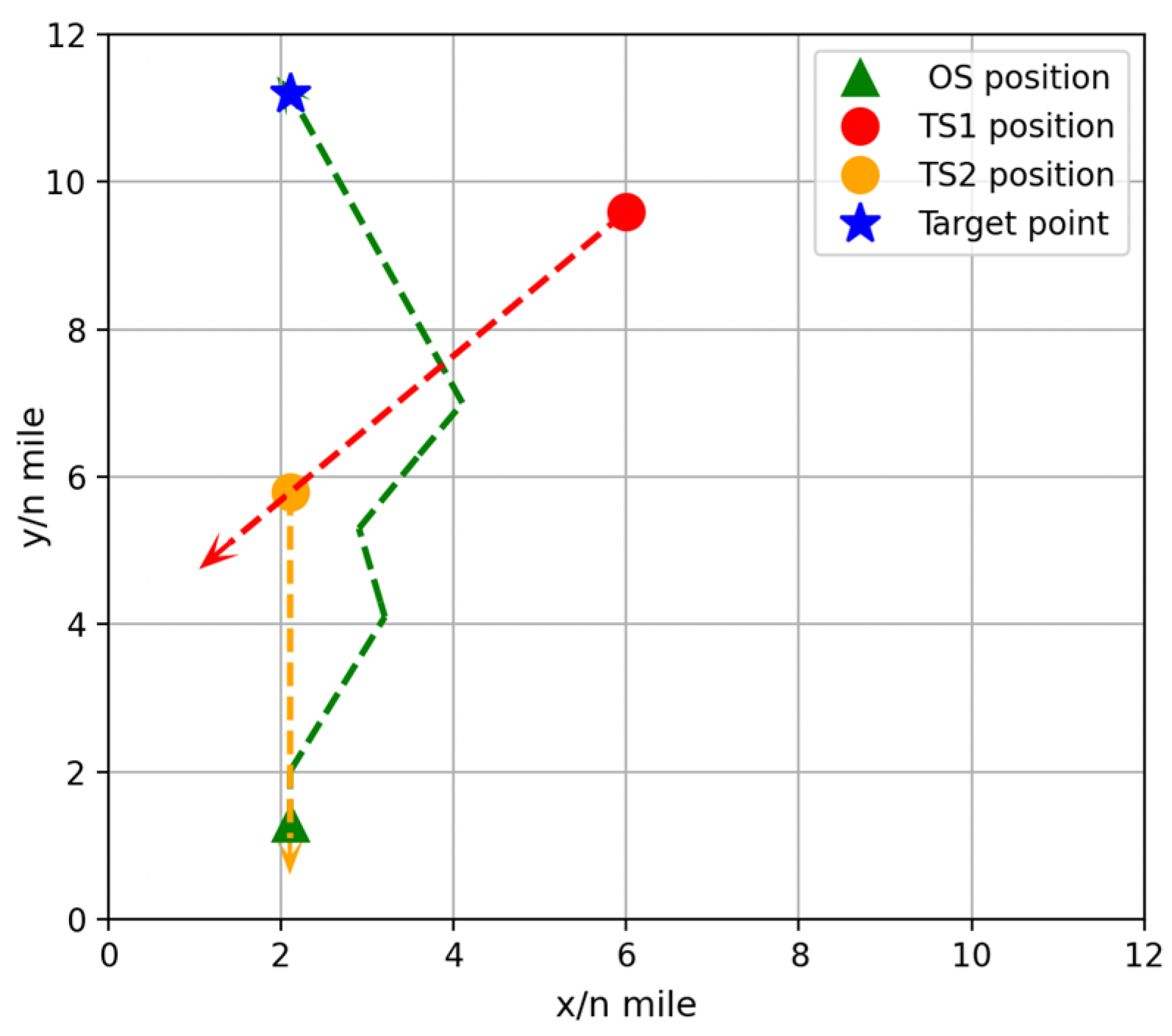

In this study, a three-ship collision avoidance scenario is simulated, and the encounter situation is determined based on the relative motion of TS with respect to OS. TS is assumed to maintain a constant speed and course, and the focus is on analyzing the avoidance behavior of OS.

- (1)

Starboard Small-Angle Crossing and Head-On Situation

The basic parameters of each ship are listed in

Table 6.

As shown in

Figure 11, OS and TS2 are in a head-on situation, so OS alters its course to starboard to give way. As TS1 approaches, OS and TS1 form a small-angle starboard crossing situation, and OS makes a second starboard alteration. In this way, OS successfully avoids both TS1 and TS2 and safely reaches its destination. In the figure, the track of OS is shown as a green dashed line, TS1 as a red dashed line, and TS2 as a yellow dashed line.

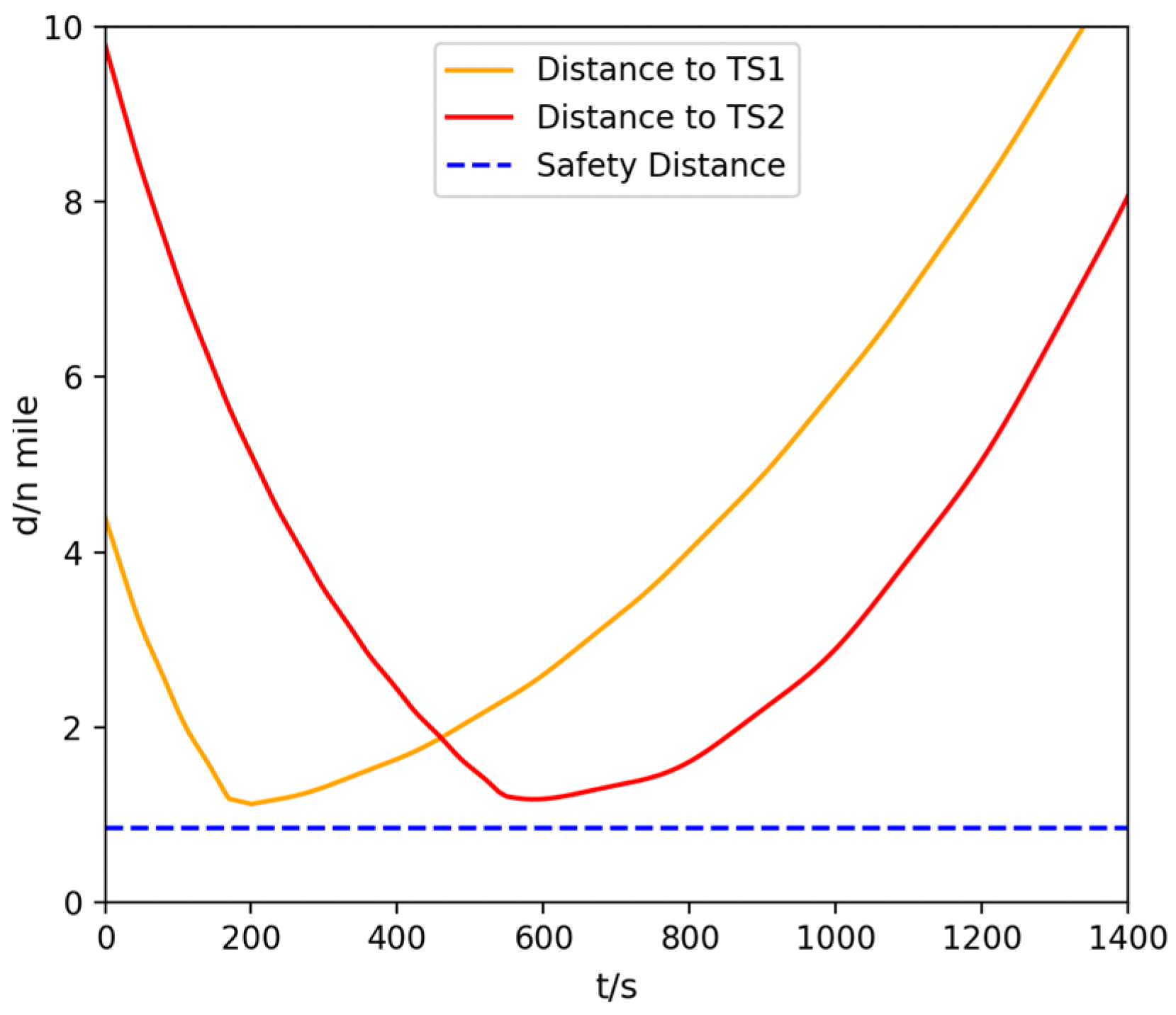

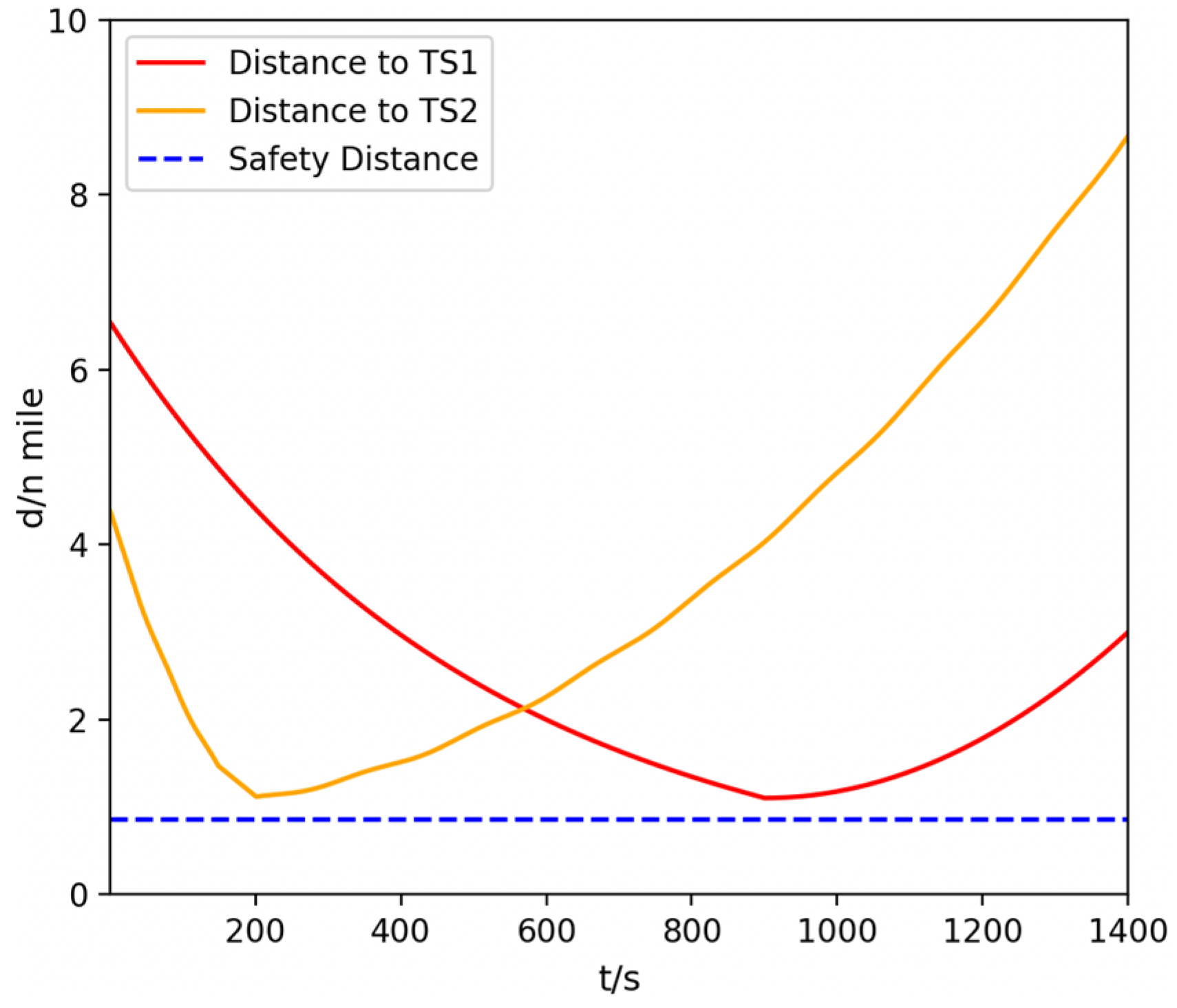

During the starboard small-angle crossing and head-on encounters, the variation in the distance between OS and TS is shown in

Figure 12. It can be seen that, throughout the collision avoidance process, the distances between OS and each TS remain greater than the safety distance of 0.85 nautical miles, thus satisfying the safety requirement.

- (2)

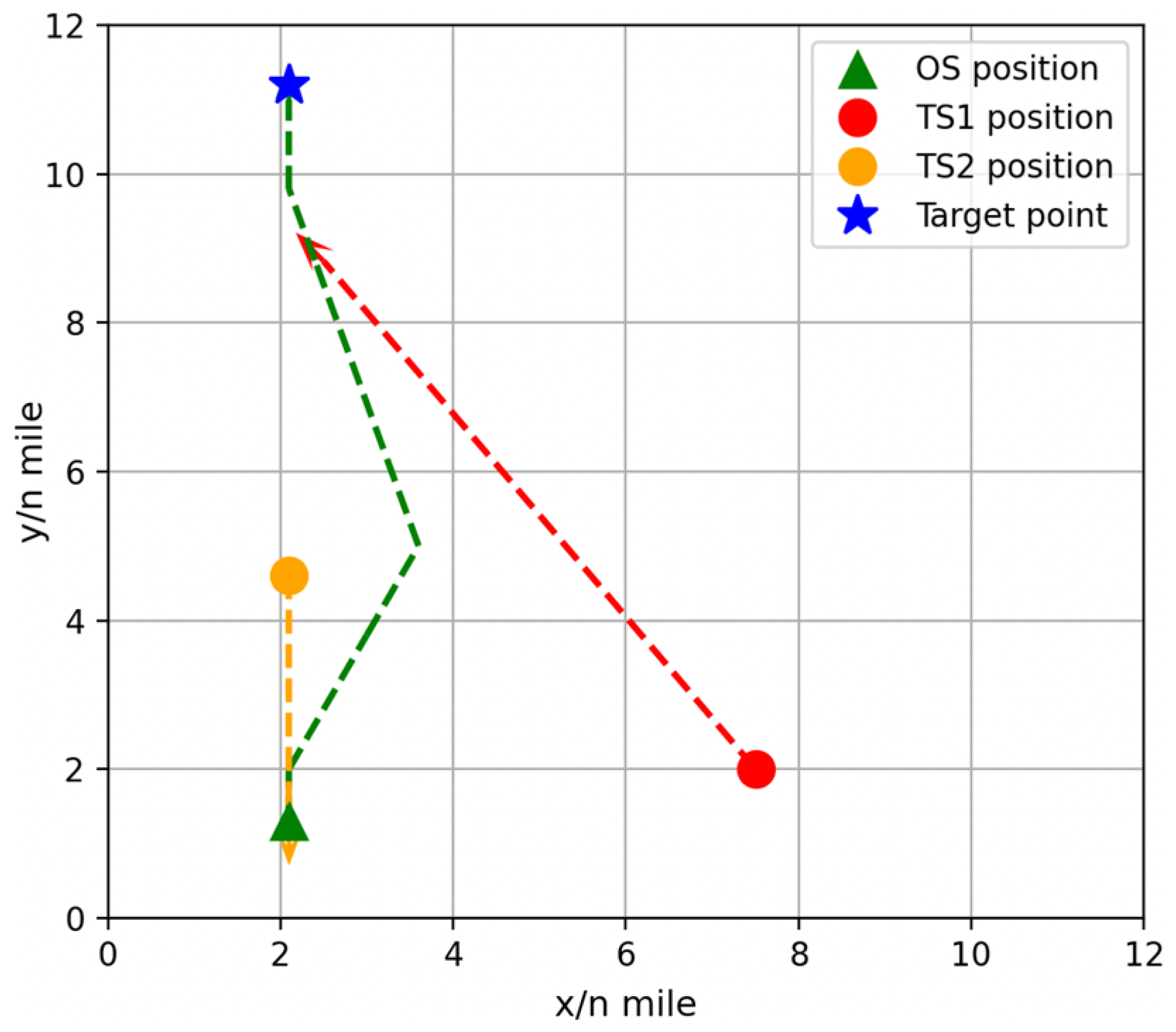

Starboard Large-Angle Crossing and Head-On Situation

The basic parameters of each ship are listed in

Table 7.

As shown in

Figure 13, OS and TS2 are in a head-on situation, so OS first alters its course to starboard to give way. As TS1 approaches, OS and TS1 form a large-angle starboard crossing situation, and OS then makes a second alteration to port, ultimately avoiding both TS1 and TS2 and safely reaching its destination. In the figure, the track of OS is shown as a green dashed line, that of TS1 as a red dashed line, and that of TS2 as a yellow dashed line.

During the starboard large-angle crossing and head-on encounters, the variation in the distance between OS and TS is shown in

Figure 14. It can be seen that, throughout the collision avoidance process, the minimum distance between OS and each TS remains greater than the safety distance, thereby satisfying the safety requirement.

3.2.2. Four-Ship Collision Avoidance Simulation

The initial course and speed of OS are

= 45° and

= 15 kn, respectively. The basic parameters of TS are given in

Table 8.

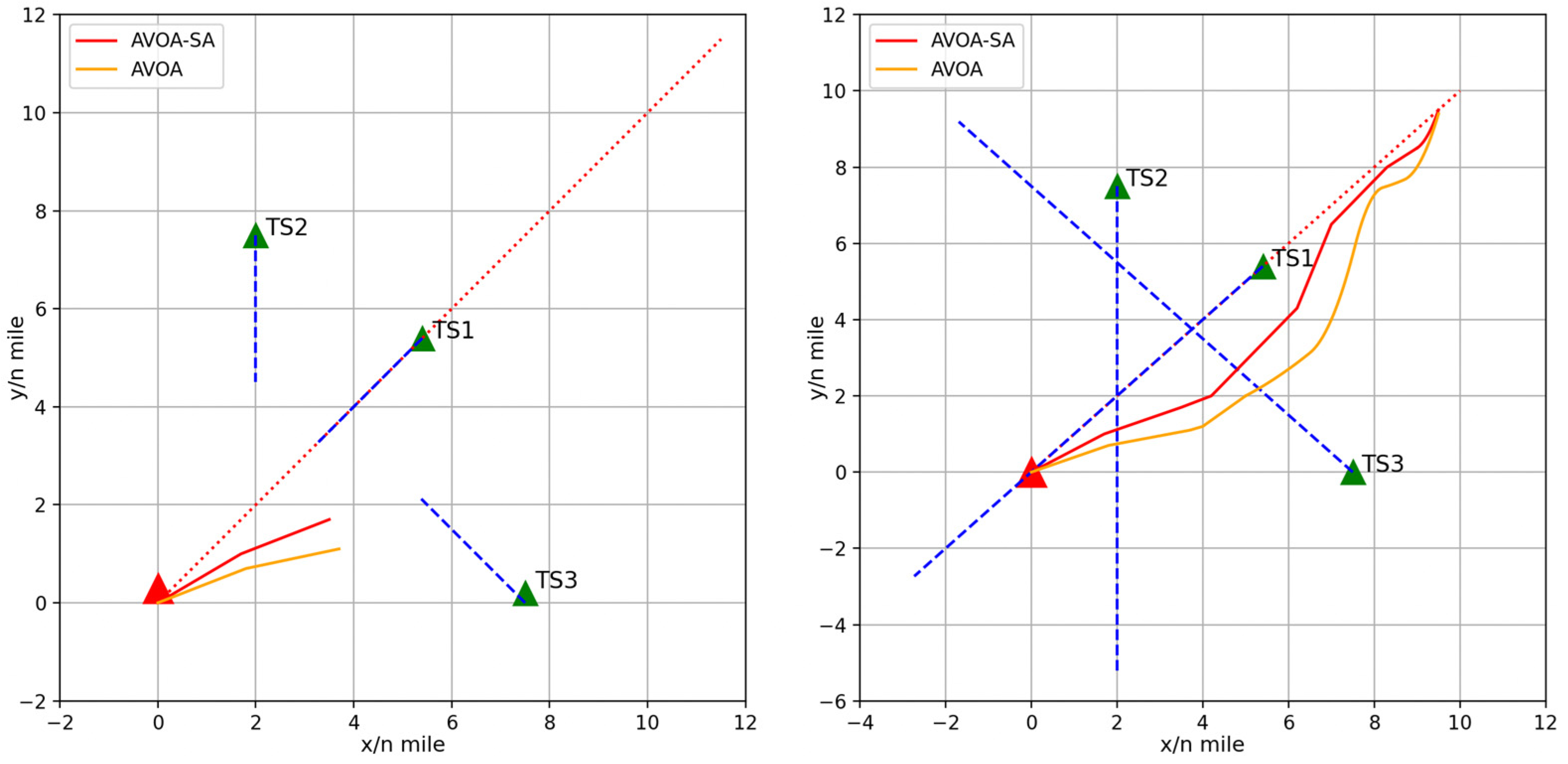

As shown in

Figure 15, in this encounter situation OS and TS1 form a head-on situation, TS2 forms a port crossing situation, and TS3 forms a small-angle starboard crossing situation. In the figure, the red triangles denote the positions of OS, the green triangles denote the positions of TS, the red dotted line represents the original course of OS, and the blue dotted lines represent the original courses of TS. The trajectory of OS planned by AVOA-SA is shown as the red solid line, while that planned by AVOA is shown as the yellow solid line.

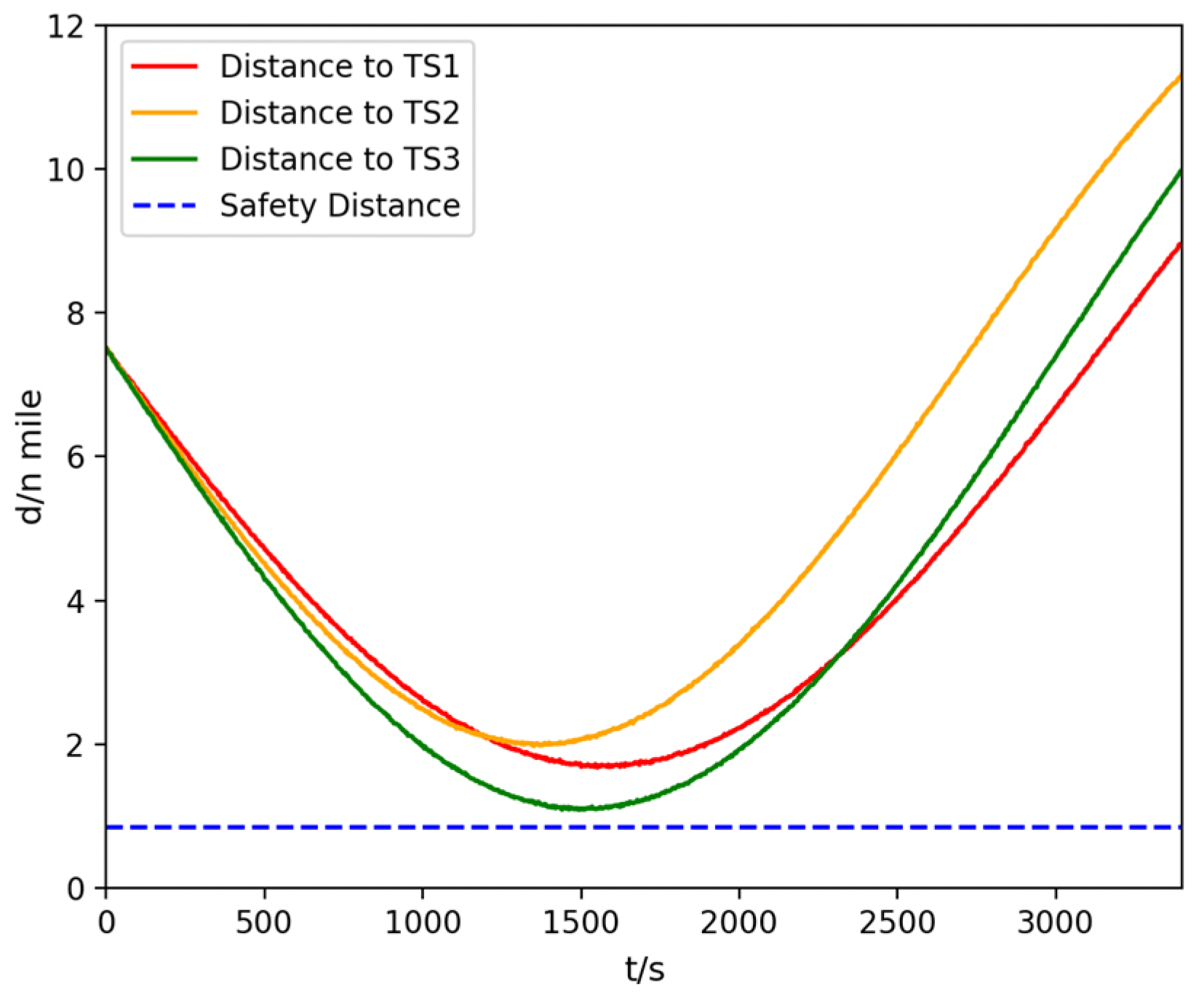

During the four-ship encounter, the curves of the minimum distance between OS and each TS are shown in

Figure 16. It can be seen that, throughout the entire collision avoidance process, the minimum distance between OS and all TS remains greater than the safety distance, thereby satisfying the safety requirements.

3.2.3. Performance Comparison

This study aims to optimize the sailing path and dynamically adjust the collision avoidance strategy to ensure safe and efficient navigation in complex environments. The simulation results show that the maneuvers of OS comply with COLREGs, and safety is verified by the distance-variation curves. The next step is to evaluate the economic performance of the planned paths.

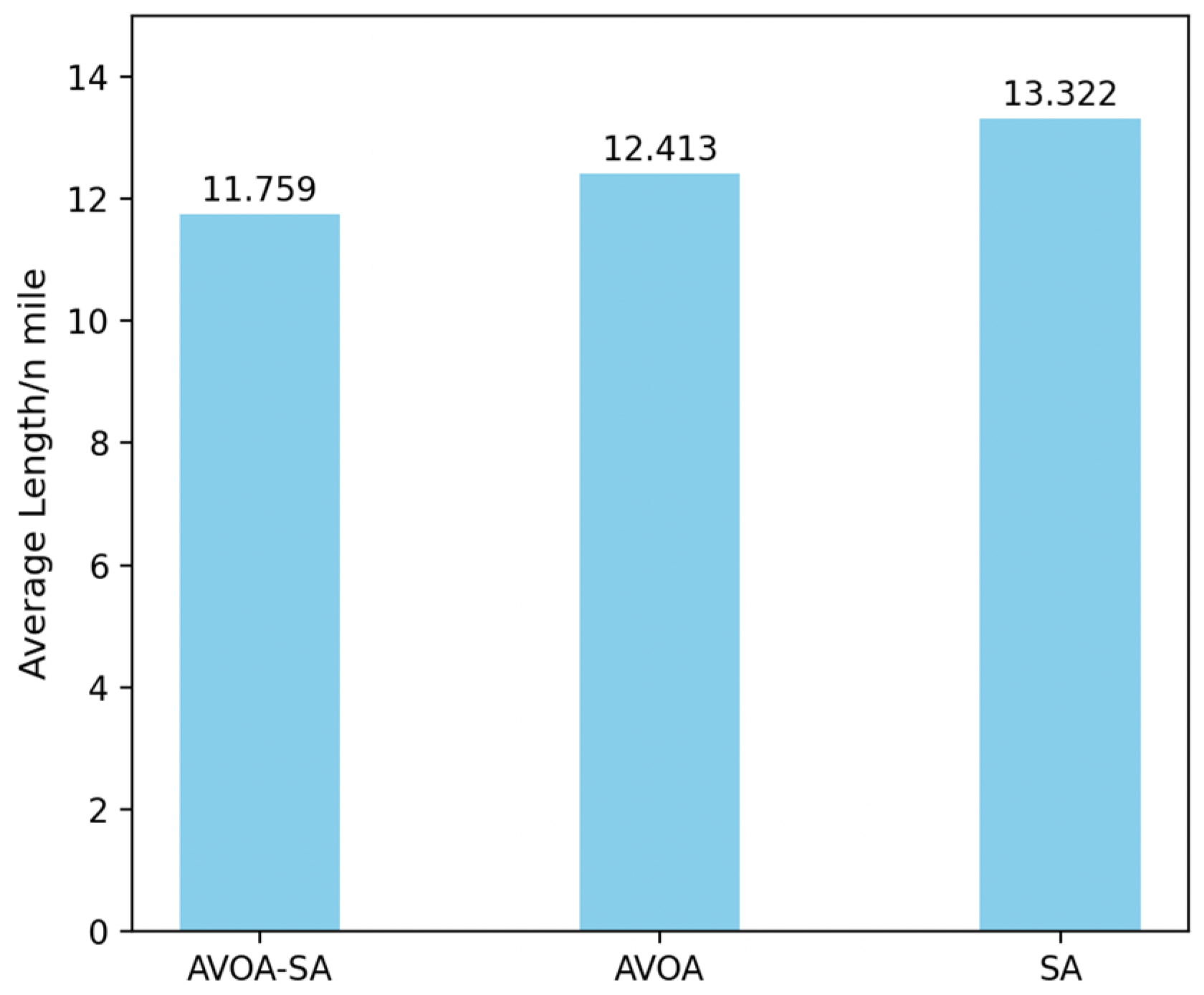

By comparing the average collision avoidance path lengths of AVOA-SA with those of other algorithms, the economic performance is verified. Using the four-ship encounter scenario as the background, AVOA-SA, standard AVOA, and SA are applied, and the average collision avoidance path lengths over 100 runs are calculated for the three algorithms. As shown in

Figure 17 over 100 runs AVOA-SA yields the shortest average collision avoidance path length. Compared with AVOA-SA, the path generated by AVOA is 5.56% longer, and that generated by SA is 13.28% longer. These results indicate that the path economy objective function effectively prevents OS from deviating excessively from its destination during collision avoidance. Therefore, the collision avoidance paths planned by AVOA-SA satisfy the economic requirements.

4. Discussion

This study investigates ship collision avoidance decision-making in open waters by proposing a CRI model based on a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method. By jointly considering navigational safety, compliance with COLREGs, turning amplitude, and path economy, a collision avoidance objective function is constructed to balance safety requirements and maneuvering efficiency.

An improved AVOA-SA is then developed to enhance optimization performance. By introducing the simulated annealing mechanism, the tendency of the original AVOA to become trapped in local optima is effectively alleviated, resulting in improved global search capability and local optimization accuracy. Benchmark function comparisons indicate that the proposed AVOA-SA exhibits favorable convergence behavior and stable performance relative to other optimization algorithms.

Collision avoidance simulations conducted on the VSC platform further demonstrate the applicability of the proposed method in both two-ship and multi-ship encounter scenarios. The results show that feasible and COLREG-compliant avoidance routes can be generated in complex multi-ship situations, while maintaining consistent convergence behavior. These results indicate that the proposed approach is suitable for supporting real-time collision avoidance decision-making in open waters.

While the results are encouraging, certain limitations remain. The proposed model is developed for ship–ship encounters in open waters under good visibility conditions, and scenarios involving fixed obstacles or restricted waters are not considered. Further work may focus on improving computational efficiency to better satisfy real-time requirements, extending the method to more complex navigational environments, and incorporating environmental disturbances such as wind, waves, and currents, as well as uncertainties in target ship behavior.