Simulation and Experimental Research on the Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Cutting Process Characteristics of Aramid Honeycomb Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

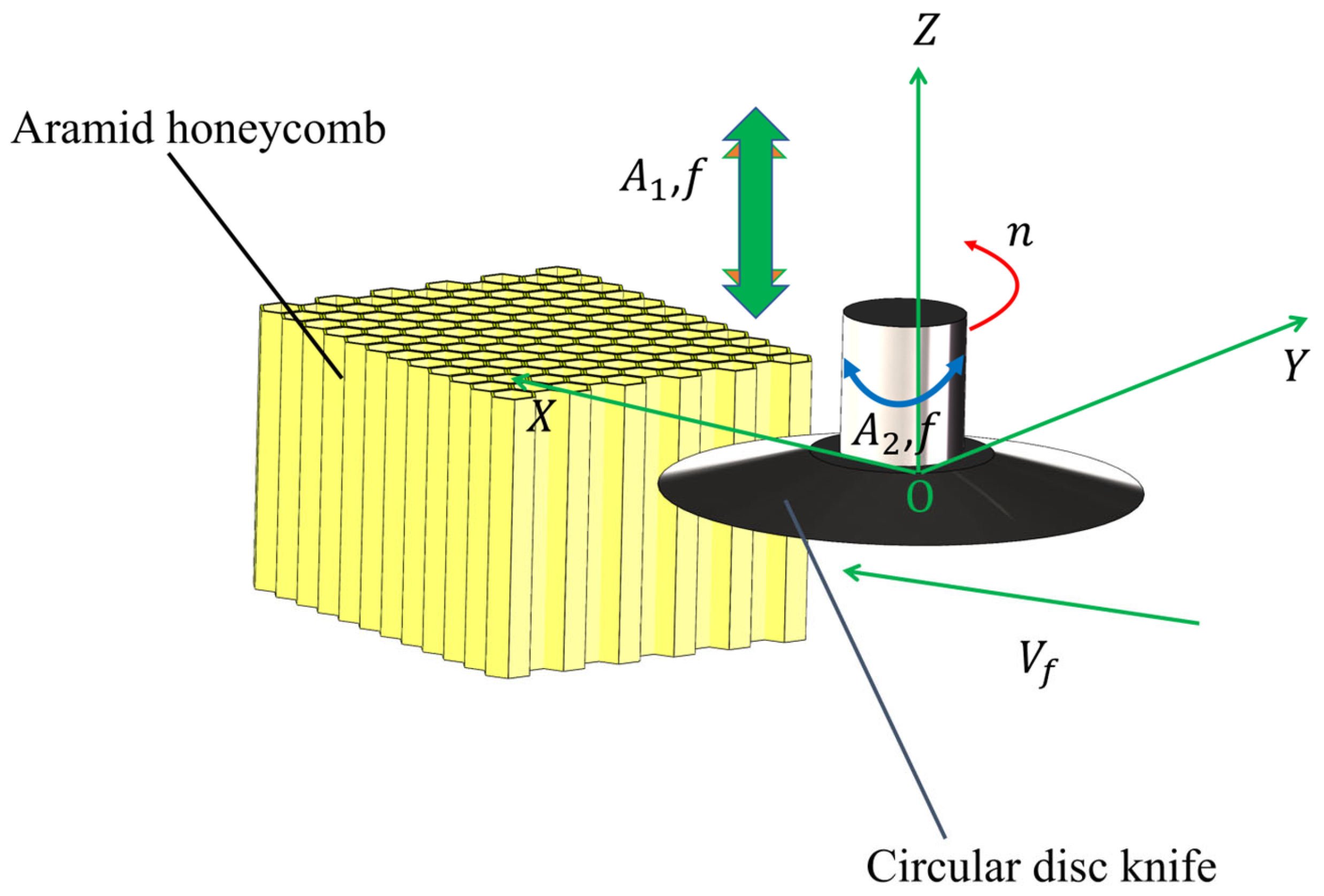

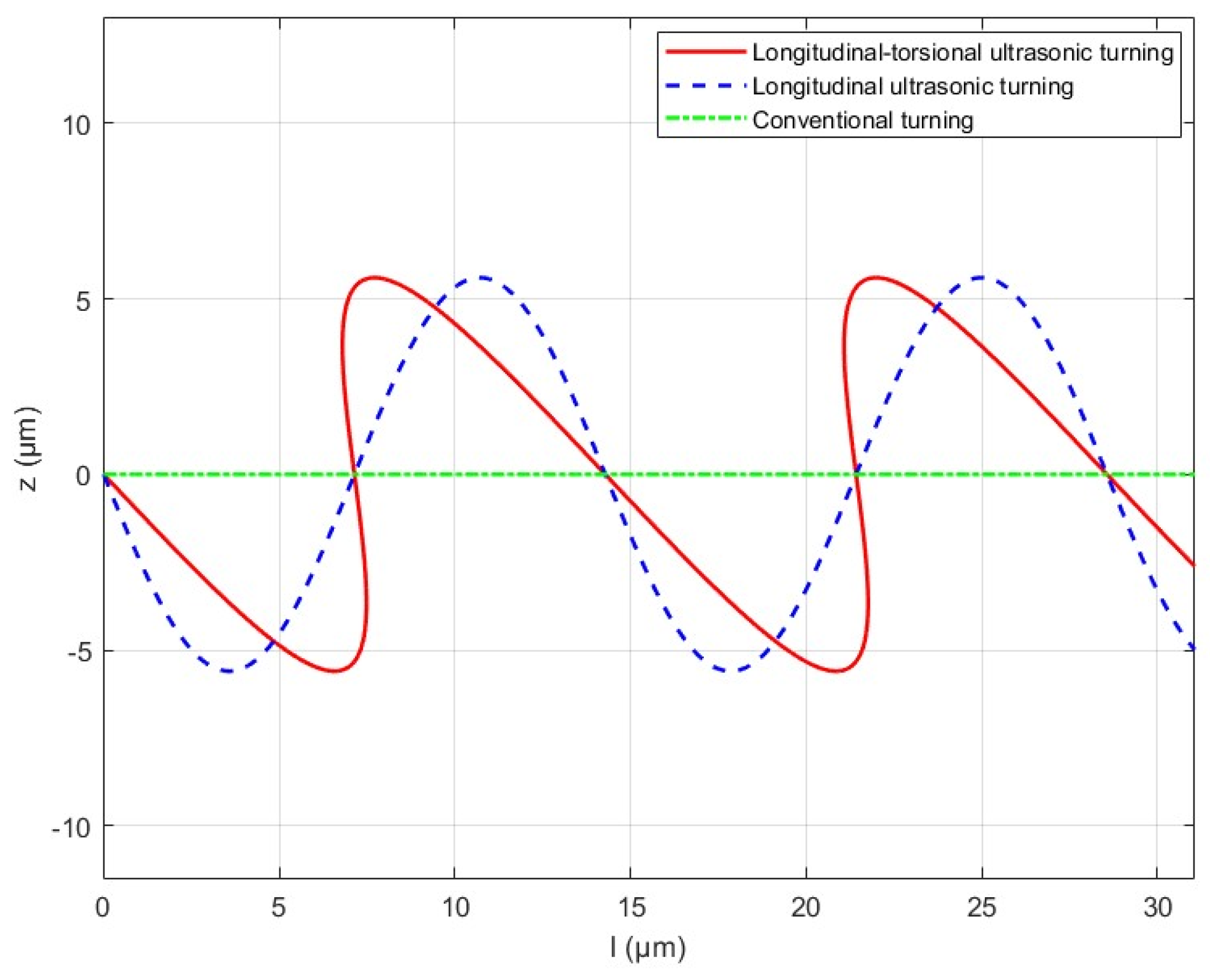

2. Analysis of Ultrasonic Cutting Motion Characteristics

3. Cutting Simulation of Aramid Honeycomb

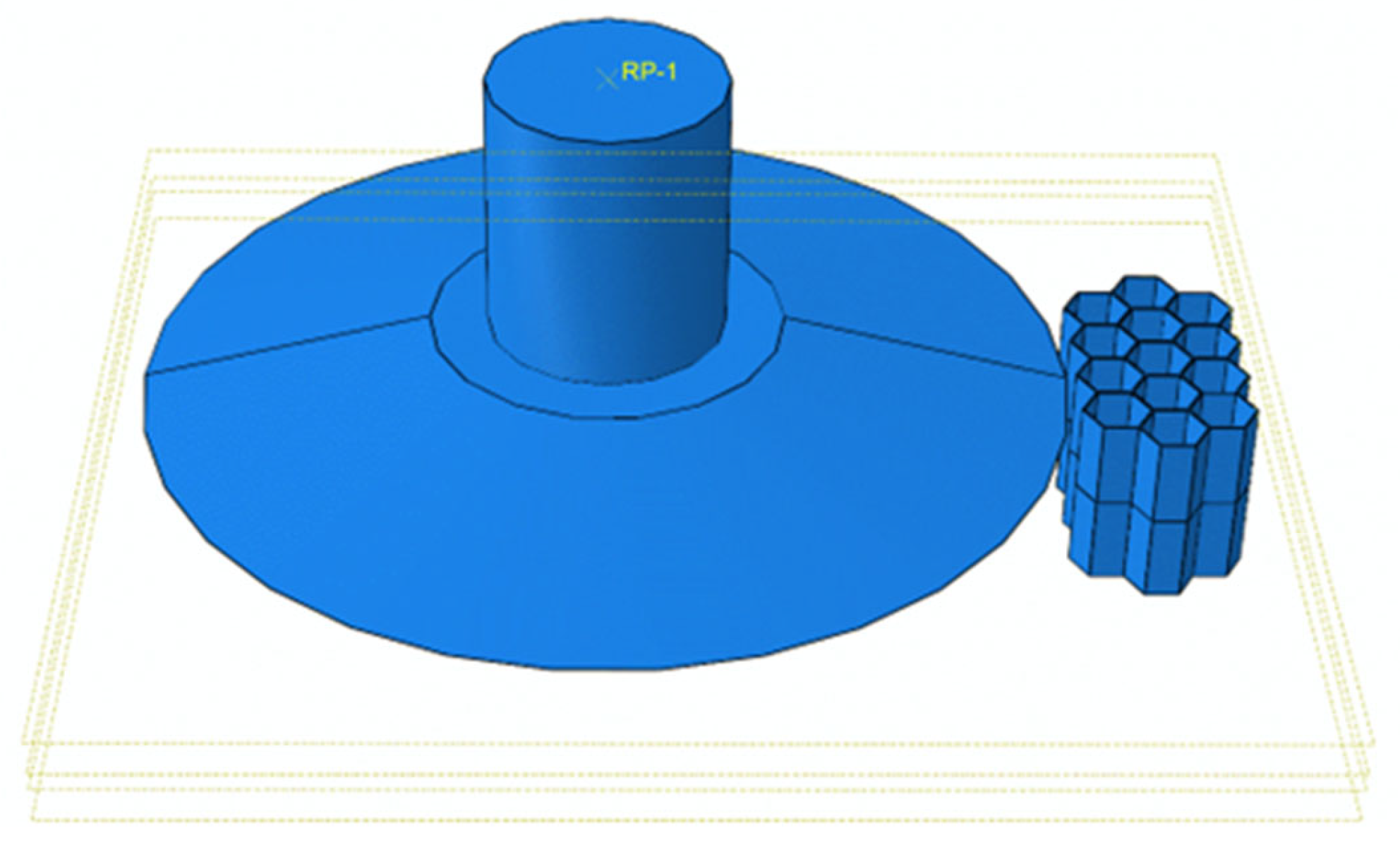

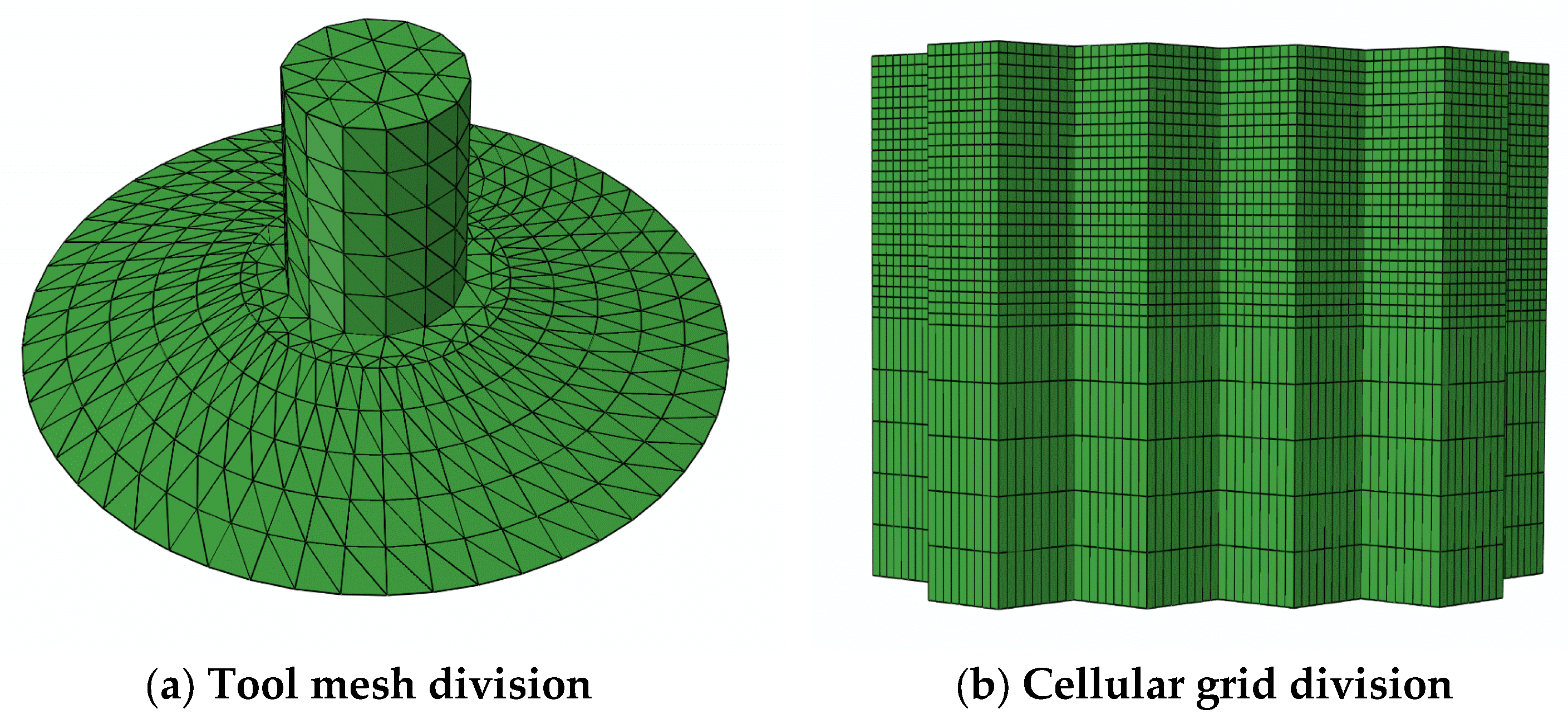

3.1. Simulation Preprocessing

3.1.1. Finite Element Modeling

3.1.2. Boundary Conditions and Contact Settings

3.1.3. Material Failure Criteria

3.2. Experimental Scheme Design

3.2.1. Ultrasonic Cutting Comparative Experiment

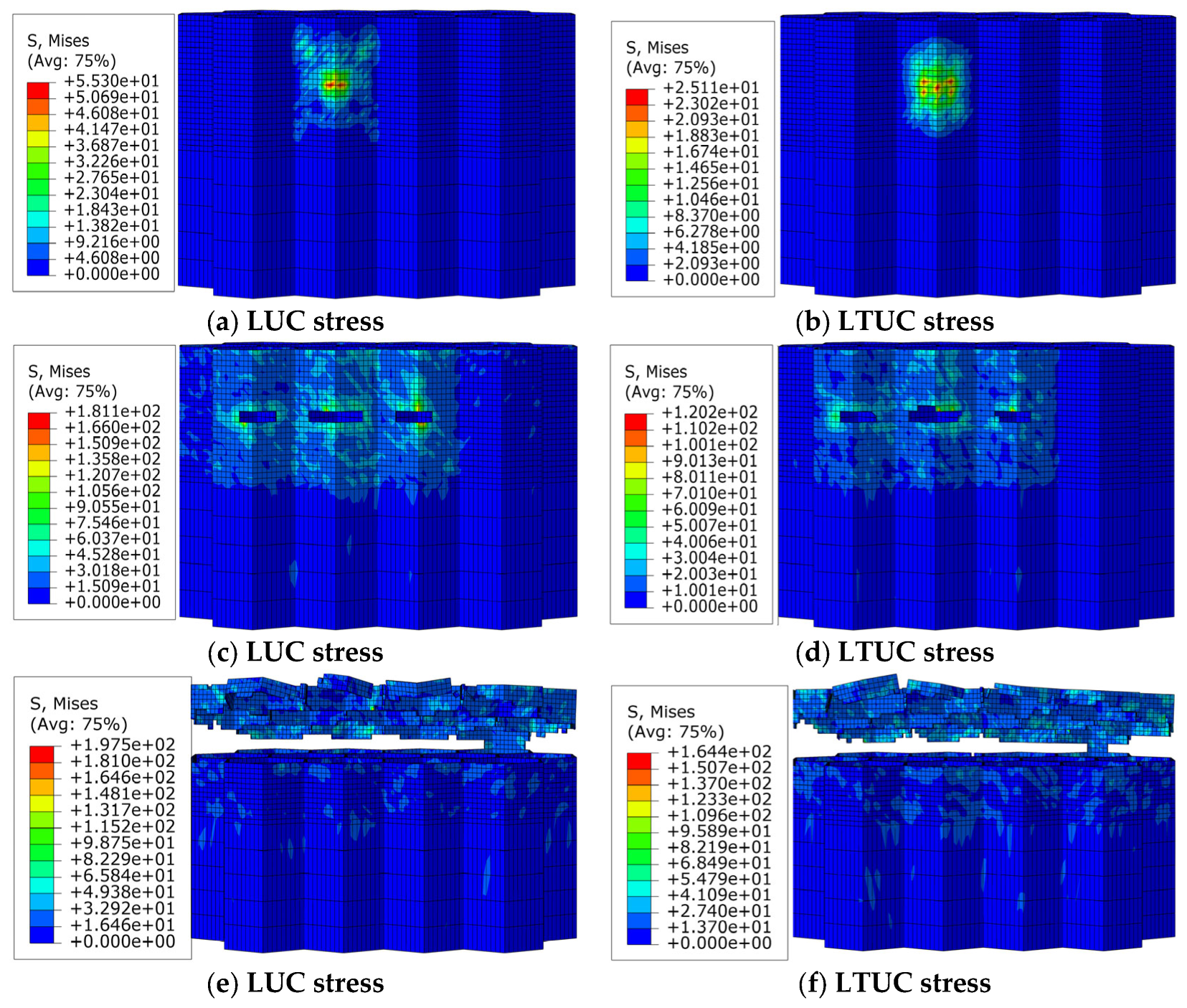

- Comparison of Cutting Stress

- 2.

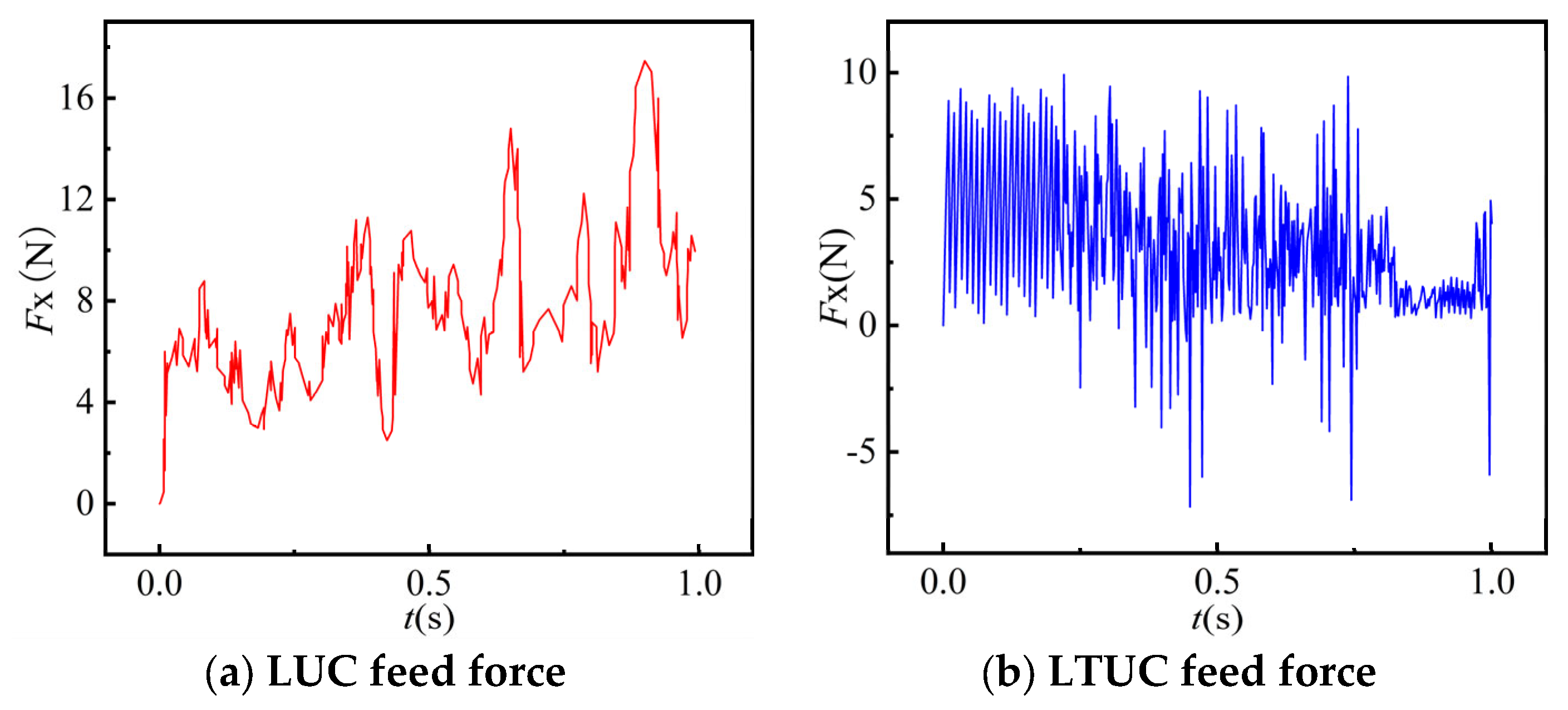

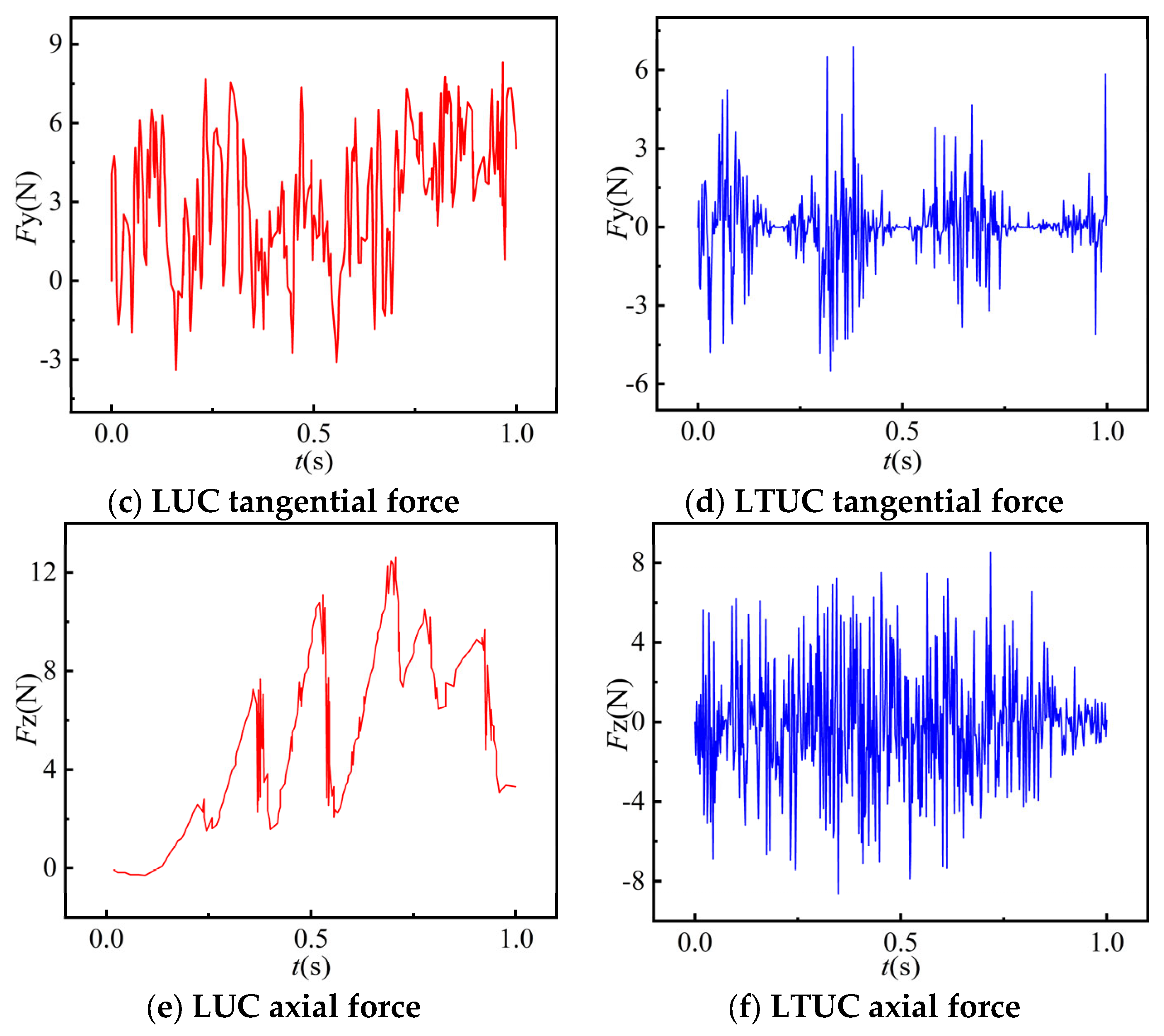

- Changes in cutting force

- 3.

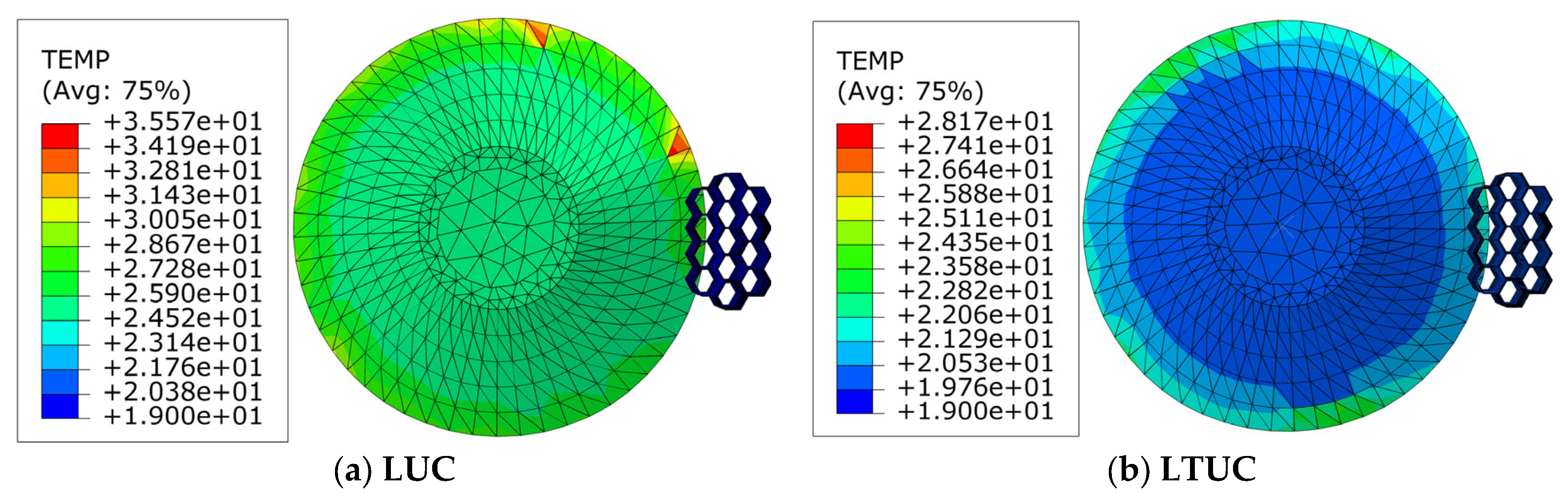

- Comparison of tool cutting temperatures

3.2.2. Single-Factor Simulation Test

- Changes in Cutting Force

- 2.

- Changes in the cutting temperature of the tool.

4. Ultrasonic Vibration Cutting Test of Aramid Honeycomb

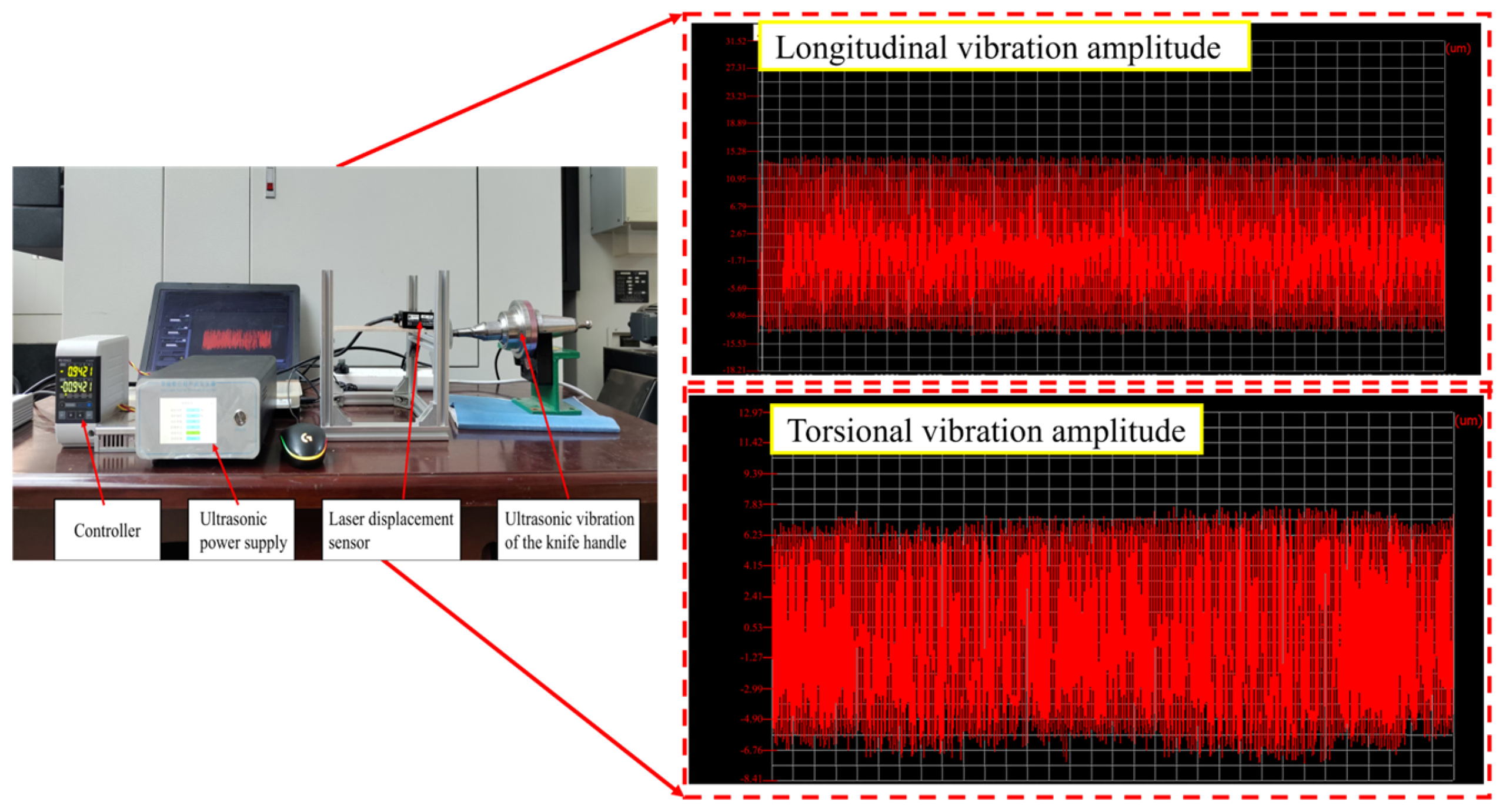

4.1. Test Conditions

4.2. Analysis of Single-Factor Test Results

4.2.1. Test Results of Cutting Force

- The influence of spindle speed on cutting force

- 2.

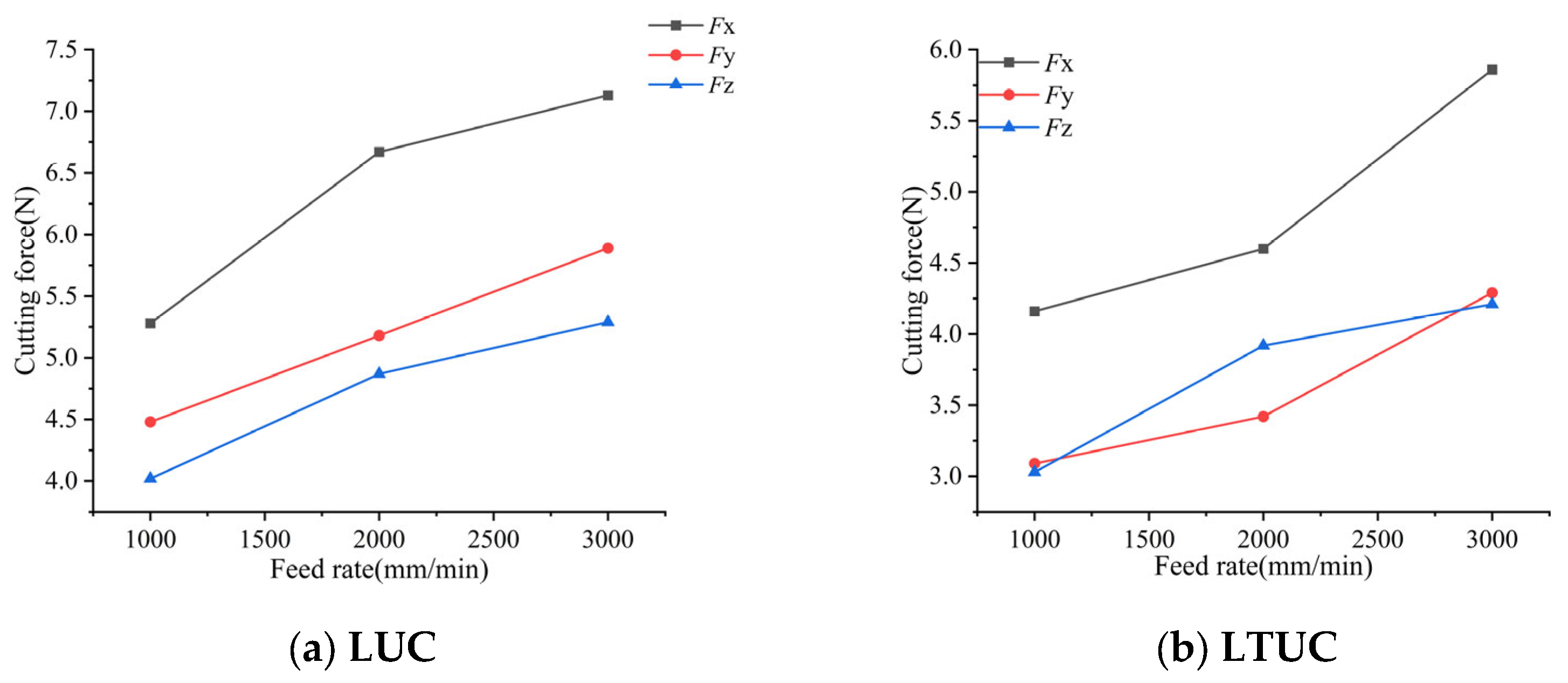

- The influence of feed rate on cutting force

- 3.

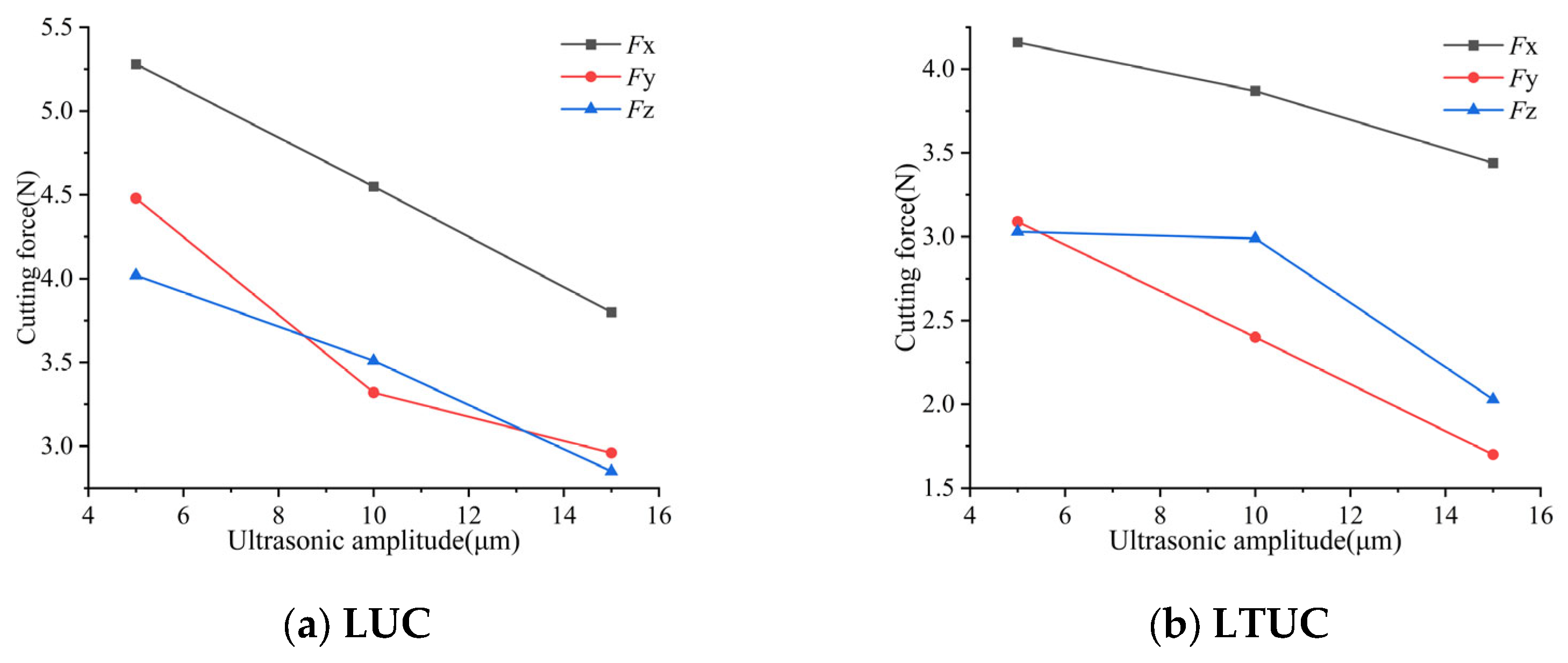

- The influence of ultrasonic amplitude on cutting force

4.2.2. Verification of the Simulation Model

4.2.3. Process Parameter Optimization

- 1.

- Spindle speed

- 2.

- Feed rate

- 3.

- Ultrasonic amplitude

5. Conclusions

- The periodic separation contact characteristics of LTUC reduce the contact time between the workpiece and the tool, increase the cutting speed of the cutting edge, improve the heat dissipation conditions during cutting, and thereby enhance the cutting efficiency.

- Compared with longitudinal vibration ultrasonic cutting, the ultrasonic longitudinal cutting of aramid honeycomb materials can further reduce cutting stress, cutting force and tool cutting temperature. The feed force decreased by an average of 28.2%, the tangential force decreased by an average of 45.8%, the axial force decreased by an average of 31.2%, and the tool temperature decreased by 21%.

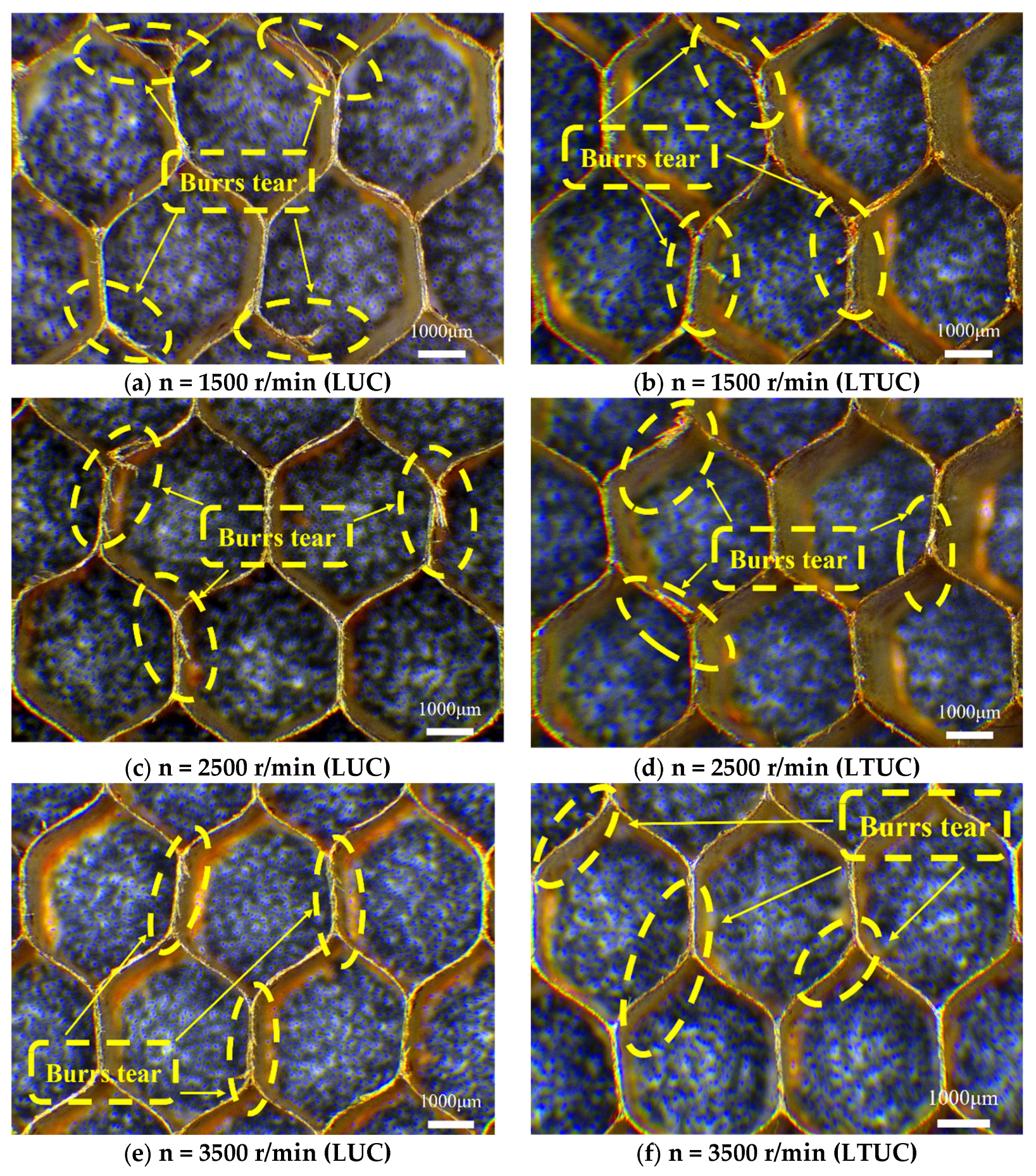

- Simulation and experiments show that the cutting forces of the two processing methods decrease with an increase in the spindle speed and ultrasonic amplitude and increase with an increase in the feed rate. The cutting temperature of the tools in both processing methods increases with an increase in the spindle speed and feed rate and decreases with an increase in the ultrasonic amplitude. Under LTUC, cutting performance is superior to LUC. Meanwhile, the surface burrs and tears of aramid honeycomb after LTUC are smaller than those after LUC, which can improve the processing quality and have better cutting process characteristics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J.; Kang, R.; Zhou, P.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Y. Review on Ultrasonic Cutting of Honeycomb Core. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.; Chen, C.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y. Effects of the tool geometry, cutting and ultrasonic vibration parameters on the cutting forces, tool wear, machined surface integrity and subsurface damages in routing of glass-fibre-reinforced honeycomb cores. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 104, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zuo, X.; Li, Z.; Guan, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. The design of continuous carbon fiber composite honeycombs and study on its properties. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 3729–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Ren, K.; Fu, J.; Yin, L.; Yang, R.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Z. Simulation study on the anti-penetration performance and energy absorption characteristics of honeycomb aluminum sandwich structure. Compos. Struct. 2023, 310, 116776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Wang, M.; Kang, R.; Dong, Z. Equivalent mechanical model of resin-coated aramid paper of Nomex honeycomb. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 240, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dang, X. Research Progress on the Preparation technology and Application of Aramid Paper Honeycomb Core Materials. New Mater. Ind. 2019, 12, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- An, Q.; Dang, J.; Ming, W.; Qiu, K.; Chen, M. Experimental and numerical studies on defect characteristics during milling of aluminum honeycomb core. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2019, 141, 031006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhu, X.; Kang, R.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z. Experimental Study on Ultrasonic Cutting of Honeycomb Core Materials by Circular Disc Cutters. Diam. Abras. Tools Eng. 2017, 37, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C. High-Efficiency Processing Tool Technology for Composite Materials. Aviat. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 6, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, D.; Su, B.; Wang, D.; Peng, P.; Yuan, Z.; Song, C.; Li, B.; Cui, X.; Gao, G.; Zhao, B. Ultrasonic longitudinal-torsional vibration helical milling internal thread of SiCp/Al composites: Finite element simulation and machining quality research. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, F.; Liu, Y.; Sha, Z. Simulation Analysis on the Influence of Tool Parameters on Cutting Force and Temperature in Ultrasonic Cutting of Honeycomb Cores. J. Dalian Jiaotong Univ. 2017, 38, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S. Implementation of new stepped horn in rotary ultrasonic machining of NOMEX honeycomb composites. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 4983–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Feng, P.; Jiang, E.; Feng, F. Meso-scale cracks initiation of Nomex honeycomb composites in orthogonal cutting with a straight blade cutter. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 233, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qin, Y.; Kang, R.; Dong, Z.; Song, H.; Wang, Y. Study on characteristics of tool wear and breakage of ultrasonic cutting Nomex honeycomb core with the disc cutter. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Zou, P.; Wu, H.; Duan, J.; Wang, W. Study on ultrasonic vibration–assisted cutting of Nomex honeycomb cores. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, H.; Khan, M.S.; Munir, A.; Zahid, D.; McDermott, O. Enhancing Cutting Efficiency and Minimizing Forces for Nomex Honeycomb Core Using Grey Relational Analysis and Desirability Function Analysis. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2300958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X. Experimental Research on Honeycomb Processing Technology of Aramid Paper for Aviation Based on 5—Axis High Speed Machining Cente. Fiber Compos. 2024, 41, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Nouari, M.; Makich, H.; Moufki, A. 3D numerical modeling and experimental validation of machining Nomex® honeycomb materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 2853–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, Z. Formation mechanism of tearing defects in machining Nomex honeycomb core. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 3167–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrouk, T.; Nouari, M.; Makich, H. Simulated study of the machinability of the Nomex honeycomb structure. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Pu, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B. Experimental Study on High-Speed Milling of Wave-absorbing Honeycomb Based on Crushing Tooth Tools. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 67, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Zha, J.; Chen, Y. Cutting force prediction and experiment verification of paper honeycomb materials by ultrasonic vibration-assisted machining. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Kang, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Dong, Z. A novel ultrasonic trepanning method for Nomex honeycomb core. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Experimental Study on Damage Inhibition in Edge Cutting Processing of NOMEX Honeycomb Materials. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Guo, F.; Huang, W.; An, Q.; Ming, W.; Chen, M. Material Removal Mechanism and Damage Behavior in High-speed Milling of High-temperature Alloy Honeycomb Core. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 58, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Duan, C.; Tian, X.; Wang, C. Mechanistic modeling considering bottom edge cutting effect and material anisotropy during end milling of aluminum honeycomb core. Compos. Struct. 2024, 327, 117686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, H.; Shang, W.; Xu, J.; Feng, F.; Kong, H.; Jiang, E.; Ma, Y.; Xu, C.; Feng, P. Tool wear characteristics and strengthening method of the disc cutter for nomex honeycomb composites machining with ultrasonic assistance. Technologies 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structural Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Longitudinal Young’s modulus (MPa) | 3000 |

| Lateral Young’s modulus (MPa) | 1700 |

| Young’s modulus in the thickness direction of aramid paper (MPa) | 1700 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.2 |

| Shear modulus (MPa) | 1200 |

| Longitudinal tensile strength (MPa) | 90 |

| Longitudinal compressive strength (MPa) | 45 |

| Transverse tensile strength (MPa) | 60 |

| Lateral compressive strength (MPa) | 30 |

| Tensile strength of aramid paper in the thickness direction (MPa) | 60 |

| Compressive strength of aramid paper in the thickness direction (MPa) | 30 |

| In-plane shear strength (MPa) | 55 |

| Density () | 72 |

| The side length of the honeycomb cell grid (mm) | 2.75 |

| Single-layer wall thickness (mm) | 0.05 |

| Length of honeycomb material (mm) | 24.6 |

| Height of honeycomb material (mm) | 10 |

| Width of honeycomb material (mm) | 14 |

| Tool Diameter (mm) | Tool Thickness (mm) | Tool Wedge Angle (°) | Tool Chamfering (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | 4 | 14 | 2 |

| Materials | Specific Heat Capacity (J/(kg·°C)) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·°C)) | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (10–6/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular disc knife | 420 | 24 | 4.5 |

| Aramid honeycomb | 1300 | 0.123 | 4 |

| Processing Method | Spindle Speed | Feed Rate | Longitudinal Amplitude | Torsional Amplitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (r/min) | (mm/min) | (μm) | (μm) | |

| LUC | 1000 | 500 | 10 | 0 |

| LTUC | 1000 | 500 | 10 | 5 |

| Experiment Number | Spindle Speed, n (r/min) | (mm/min) | (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1500 | 1000 | 5 |

| 2 | 2500 | 1000 | 5 |

| 3 | 3500 | 1000 | 5 |

| Experiment Number | Spindle Speed, n (r/min) | (mm/min) | (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1500 | 1000 | 5 |

| 2 | 1500 | 2000 | 5 |

| 3 | 1500 | 3000 | 5 |

| Experiment Number | Spindle Speed, n (r/min) | (mm/min) | (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1500 | 1000 | 5 |

| 2 | 1500 | 1000 | 10 |

| 3 | 1500 | 1000 | 15 |

| Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Vibration | Longitudinal Ultrasonic Vibration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibration Frequency (kHz) | Electric Current (A) | Longitudinal Vibration Amplitude (μm) | Torsional Vibration Amplitude (μm) | Vibration Frequency (kHz) | Electric Current (A) | Longitudinal Vibration Amplitude (μm) |

| 30 | 0.21 | 5 | 2.5 | 30 | 0.18 | 5 |

| 30 | 0.45 | 10 | 5 | 30 | 0.37 | 10 |

| 30 | 0.63 | 15 | 7.5 | 30 | 0.56 | 15 |

| Processing Method | Variable Factor | Change Quantity Value | Feed Force, | Tangential Force, | Axial Force, | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Cutting Force | Experimental Cutting Force | Relative Error | Simulation Cutting Force | Experimental Cutting Force | Relative Error | Simulation Cutting Force | Experimental Cutting Force | Relative Error | |||

| Longitudinal ultrasonic cutting | Spindle speed (r/min) | 1500 | 4.78 | 5.28 | 9.5 | 3.97 | 4.48 | 11.39 | 3.56 | 4.02 | 11.45 |

| 2500 | 4.11 | 4.87 | 15.61 | 2.98 | 3.4 | 12.36 | 3.07 | 3.36 | 8.64 | ||

| 3500 | 3.94 | 4.51 | 12.64 | 2.75 | 2.95 | 6.78 | 2.89 | 3.12 | 7.38 | ||

| Feed rate (mm/min) | 1000 | 4.78 | 5.28 | 9.5 | 3.97 | 4.48 | 11.39 | 3.56 | 4.02 | 11.45 | |

| 2000 | 5.72 | 6.67 | 14.25 | 4.49 | 5.18 | 13.33 | 4.32 | 4.87 | 11.30 | ||

| 3000 | 6.21 | 7.13 | 12.91 | 5.42 | 5.89 | 7.98 | 4.92 | 5.29 | 7 | ||

| Ultrasonic amplitude (μm) | 5 | 4.78 | 5.28 | 9.5 | 3.97 | 4.48 | 11.39 | 3.56 | 4.02 | 11.45 | |

| 10 | 4.21 | 4.55 | 7.48 | 2.86 | 3.32 | 13.86 | 2.83 | 3.51 | 19.38 | ||

| 15 | 3.95 | 3.80 | 3.8 | 2.52 | 2.96 | 14.87 | 2.60 | 2.85 | 8.78 | ||

| Longitudinal torsion ultrasonic cutting | Spindle speed (r/min) | 1500 | 3.67 | 4.16 | 11.78 | 2.59 | 3.09 | 16.19 | 2.84 | 3.03 | 6.28 |

| 2500 | 3.51 | 3.88 | 9.54 | 2.41 | 2.75 | 12.37 | 2.57 | 2.97 | 13.47 | ||

| 3500 | 2.97 | 3.54 | 16.11 | 1.46 | 2.12 | 31.14 | 1.91 | 1.68 | 12.05 | ||

| Feed rate (mm/min) | 1000 | 3.67 | 4.16 | 11.78 | 2.59 | 3.09 | 16.19 | 2.84 | 3.03 | 6.28 | |

| 2000 | 4.15 | 4.60 | 9.79 | 2.78 | 3.42 | 18.72 | 3.36 | 3.92 | 14.29 | ||

| 3000 | 5.03 | 5.86 | 14.17 | 3.71 | 4.29 | 13.52 | 3.96 | 4.21 | 5.94 | ||

| Ultrasonic amplitude (μm) | 5 | 3.67 | 4.16 | 11.78 | 2.59 | 3.09 | 16.19 | 2.84 | 3.03 | 6.28 | |

| 10 | 3.43 | 3.87 | 11.37 | 1.95 | 2.40 | 18.75 | 2.36 | 2.99 | 21.08 | ||

| 15 | 2.98 | 3.44 | 13.38 | 1.51 | 1.70 | 11.18 | 1.91 | 2.03 | 5.92 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, L.; Meng, T.; Wang, X. Simulation and Experimental Research on the Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Cutting Process Characteristics of Aramid Honeycomb Materials. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031362

Zhang M, Zhang X, Li L, Zhang Y, Fang L, Meng T, Wang X. Simulation and Experimental Research on the Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Cutting Process Characteristics of Aramid Honeycomb Materials. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031362

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingxing, Xinpeng Zhang, Linbin Li, Yuzhu Zhang, Liyuan Fang, Ting Meng, and Xiaodong Wang. 2026. "Simulation and Experimental Research on the Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Cutting Process Characteristics of Aramid Honeycomb Materials" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031362

APA StyleZhang, M., Zhang, X., Li, L., Zhang, Y., Fang, L., Meng, T., & Wang, X. (2026). Simulation and Experimental Research on the Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Cutting Process Characteristics of Aramid Honeycomb Materials. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031362