Modeling and Optimization of Phenolic Compound Adsorption from Olive Wastewater Using XAD-4 Resin, Activated Carbon, and Chitosan Biosorbent

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Materials

2.2. Extraction and Preparation of Chitosan Biosorbent

2.3. Characterization of OMWW and Adsorbents

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherms

2.4.1. Kinetics of Adsorption

2.4.2. Adsorption Isotherms

2.4.3. Experimental Design and Optimization of Adsorption Experiments by RSM

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of OMWW

3.2. Characterization of the Adsorbents Before and After TPhC Adsorption from OMWW

3.2.1. Elemental Analysis

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis

3.2.3. Morphological Characteristics of the Used Adsorbents During Polyphenol Adsorption from OMWW

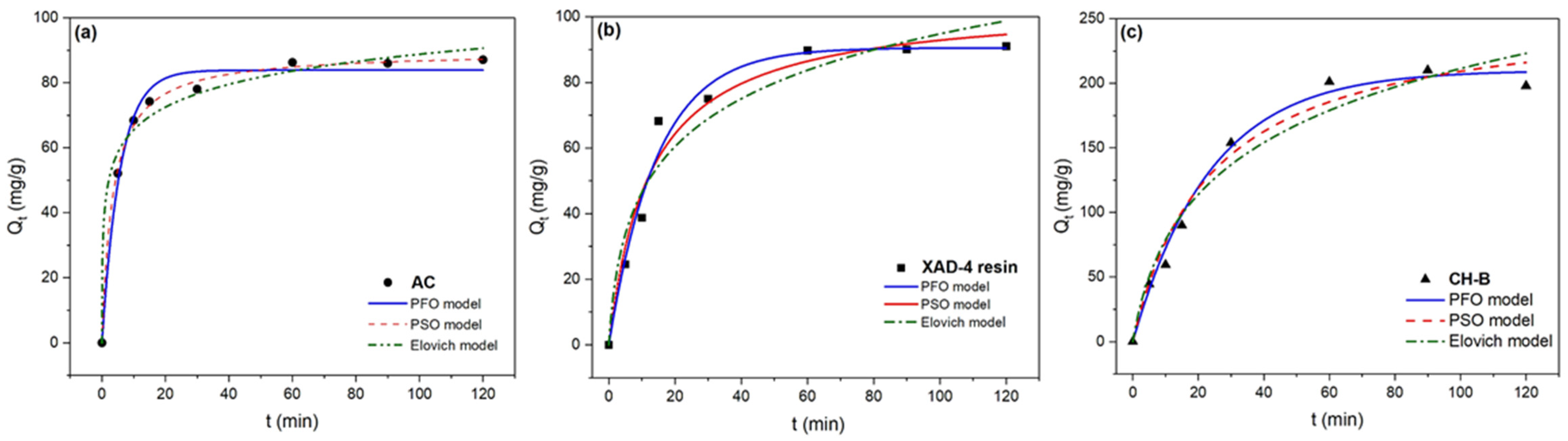

3.3. Batch Adsorption Kinetics

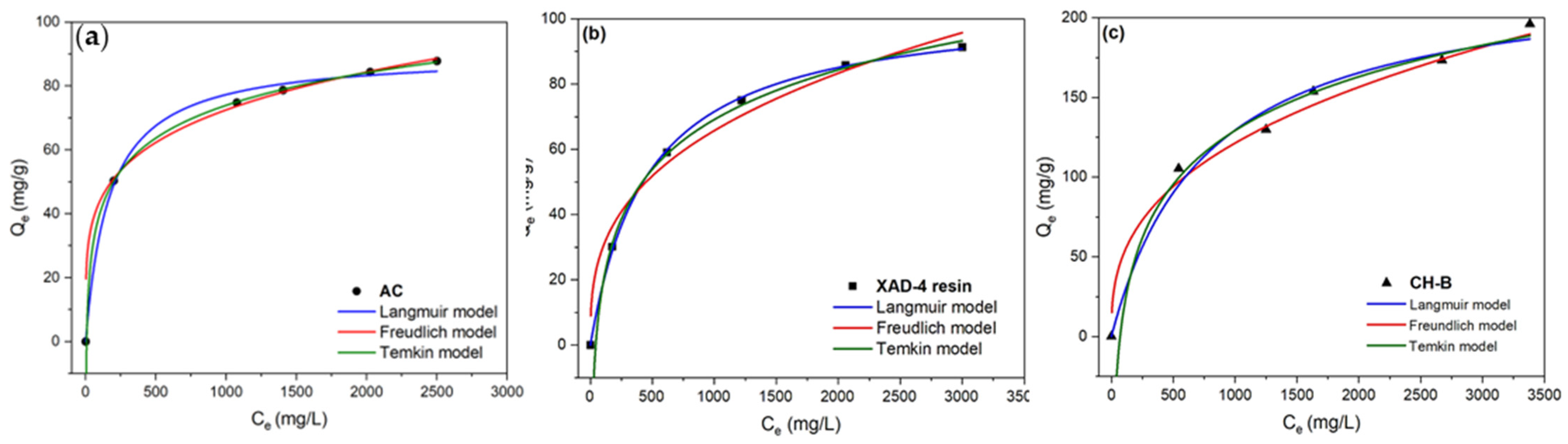

3.4. Batch Adsorption Isotherms

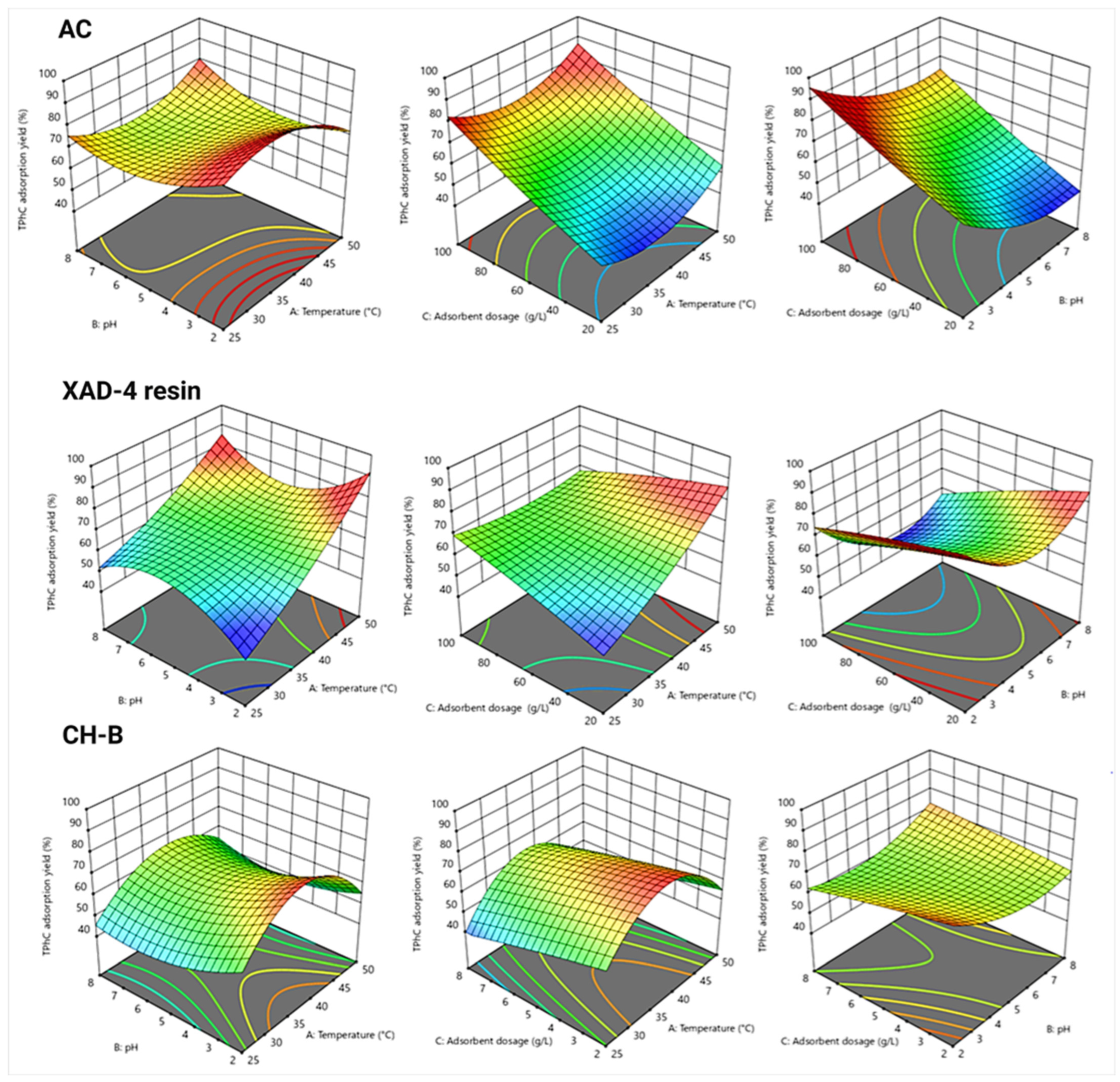

3.5. Adsorption Performance, Process Modeling, and Optimization by Response Surface Methodology

3.5.1. Model Adequacy Checking and Statistical Analysis

3.5.2. Analysis of Process Interactions and Optimization of Operating Conditions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Olive Council (IOC). World Olive Oil Figures—2023/24 Season. 2024. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/economic-affairs-promotion-unit/#figures (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Vaz, T.; Quina, M.M.J.; Martins, R.C.; Gomes, J. Olive Mill Wastewater Treatment Strategies to Obtain Quality Water for Irrigation: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermeche, S.; Nadour, M.; Larroche, C.; Moulti-Mati, F.; Michaud, P. Olive Mill Wastes: Biochemical Characterizations and Valorization Strategies. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1532–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dich, A.; Abdelmoumene, W.; Belyagoubi, L.; Assadpour, E.; Belyagoubi Benhammou, N.; Zhang, F.; Jafari, S.M. Olive Oil Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review on Examination of Toxicity, Valorization Strategies, Composition, and Modern Management Approaches; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; ISBN 1135602536127. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.H.; Juang, R.S. Adsorption of Phenol and Its Derivatives from Water Using Synthetic Resins and Low-Cost Natural Adsorbents: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girometti, E.; Frascari, D.; Pinelli, D.; Di Federico, V.; Libero, G.; Ciriello, V. Polyphenol Adsorption and Recovery from Olive Mill Wastewater: A Model Reduction-Based Optimization and Economic Assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.; Lee, K.C. Removal of Phenols from Aqueous Solution by XAD-4 Resin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 80, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojoudi, N.; Mirghaffari, N.; Soleimani, M.; Shariatmadari, H.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Phenol Adsorption on High Microporous Activated Carbons Prepared from Oily Sludge: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Li, D.; Wang, L.j. Functionalized Nanocomposite Biopolymer-Based Environmental-Friendly Adsorbents: Design, Adsorption Mechanism, Regeneration, and Degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 363, 132034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, E.; Daraei, P.; Arabi Shamsabadi, A. A Review on Chitosan-Based Adsorptive Membranes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E.; Wilson, L.D.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; Balasubramanian, P.; Li, F. Chitosan-Based Materials for Emerging Contaminants Removal: Bibliometric Analysis, Research Progress, and Directions. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, V.; Murugan, S.; Kumaresan, R.; Narayanan, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Viet N Vo, D.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Jenis, P.; Potdar, P.; Gadiya, S. Sustainable Adsorbents for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J.; Amin, N.A.S.; Shahzad, K. A Review on Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Water by Adsorption. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 12842–12860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Reina, L.J.; Rodríguez-Cortina, J.; Vaillant, F.; Herrera-Orozco, I.; Carazzone, C.; Sierra, R. Extraction of Fermentable Sugars and Phenolic Compounds from Colombian Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) Nut Shells Using Subcritical Water Technology: Response Surface Methodology and Chemical Profiling. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 20, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fseha, Y.H.; Shaheen, J.; Sizirici, B. Phenol Contaminated Municipal Wastewater Treatment Using Date Palm Frond Biochar: Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayadi, F.; Boumya, W.; Achak, M.; Chhiti, Y.; Alaoui, F.E.M.; Barka, N.; Adlouni, C.E. Experimental and Modeling Studies of the Removal of Phenolic Compounds from Olive Mill Wastewater by Adsorption on Sugarcane Bagasse. Environ. Challenges 2021, 4, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouali, S.; Ait Hamdan, Y.; Benali, S.; Lhomme, P.; Gosselin, M.; Raquez, J.M.; Rhazi, M. Extraction of Chitin and Chitosan from Hermetia illucens Breeding Waste: A Greener Approach for Industrial Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 285, 138302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhadj, R.; Labidi, A.; Salaberria, A.M.; Labidi, J. Comparative Adsorption of Anionic Dye Congo Red and Purification of Olive Mill Wastewater by Chitin and Their Derivatives. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 220, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmeis, R.M.A.; Tarawneh, I.N.; Issa, A.T. Removal of Phenolic Compounds from Olive Mill Wastewater Using Chitosan/Kaolinite/Iron Oxide Nanocomposites. Water Sci. Technol. 2025, 92, 1360–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmane, E.M.; Taourirte, M.; Eladlani, N.; Rhazi, M. Extraction and Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan from Parapenaeus Longirostris from Moroccan Local Sources. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2014, 19, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalami, D.; Carrère, H.; Abdelouahdi, K.; Oukarroum, A.; Dhiba, D.; Arji, M.; Barakat, A. Combination of Dry Milling and Separation Processes with Anaerobic Digestion of Olive Mill Solid Waste: Methane Production and Energy Efficiency. Molecules 2018, 23, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, N.; Sari, F.; Velioglu, Y.S. Effects of Extraction Solvents on Concentration and Antioxidant Activity of Black and Black Mate Tea Polyphenols Determined by Ferrous Tartrate and Folin-Ciocalteu Methods. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, S. Kinetic Models of Sorption: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 276, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S. Review of Second-Order Models for Adsorption Systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.C.; Tseng, R.L.; Juang, R.S. Characteristics of Elovich Equation Used for the Analysis of Adsorption Kinetics in Dye-Chitosan Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 150, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Subbaiah, M.V.; Reddy, A.S.; Krishnaiah, A. Biosorption of Phenolic Compounds from Aqueous Solutions onto Chitosan-Abrus Precatorius Blended Beads. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhoo, A. Unveiling New Insights: Revised Temkin Adsorption Isotherm Parameters from Fresh Curve Fits in Adsorption Studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 311, 121585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; You, S.; Hosseini-bandegharaei, A. Mistakes and Inconsistencies Regarding Adsorption of Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2017, 120, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareda, J.P. On Validity, Physical Meaning, Mechanism Insights and Regression of Adsorption Kinetic Models. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 376, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahkouhmahali, E.; Mohamadzadeh, J. Optimization of Phenolic Compounds Extraction from Olive Mill Wastewater Using Response Surface Methodology. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 2400–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmaz, H.; Kartal, T.; Yildiz, S.Y. Environmental Health Optimization of Lead Adsorption of Mordenite by Response Surface Methodology: Characterization and Modification. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Víctor-Ortega, M.D.; Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Airado-Rodríguez, D.; Martínez-Férez, A. Experimental Design for Optimization of Olive Mill Wastewater Final Purification with Dowex Marathon C and Amberlite IRA-67 Ion Exchange Resins. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 34, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleyfel, L.M.; Leitner, N.K.V.; Deborde, M.; Matta, J.; El Najjar, N.H. Olive Oil Liquid Wastes–Characteristics and Treatments: A Literature Review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace Pavithra, K.; Sundar Rajan, P.; Arun, J.; Brindhadevi, K.; Hoang Le, Q.; Pugazhendhi, A. A Review on Recent Advancements in Extraction, Removal and Recovery of Phenols from Phenolic Wastewater: Challenges and Future Outlook. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamadneh, I.; Abu-Zurayk, R.A.; Al-Dujaili, A.H. Removal of Phenolic Compounds from Aqueous Solution Using MgCl2-Impregnated Activated Carbons Derived from Olive Husk: The Effect of Chemical Structures. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 81, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrotos, K.B.; Gkoutsidis, P.E.; Kokkora, M.I.; Giankidou, K.G.; Tsagkarelis, A.G. A Study on the Kinetics of Olive Mill Wastewater (OMWW) Polyphenols Adsorption on the Commercial XAD4 Macroporous Resin. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013, 51, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Sillanpää, M. Applications of Chitin- and Chitosan-Derivatives for the Detoxification of Water and Wastewater—A Short Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 152, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Barreto, D.F.; Giraldo, L.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C. Dataset on Adsorption of Phenol onto Activated Carbons: Equilibrium, Kinetics and Mechanism of Adsorption. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan: Properties and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomakou, N.; Goula, A.M. Treatment of Olive Mill Wastewater by Adsorption of Phenolic Compounds. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 20, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkakati, P.; Begum, A.; Das, M.L.; Rao, P.G. Adsorptive Separation of Ginsenoside from Aqueous Solution by Polymeric Resins: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 161, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, R.S.; Yeh, C.L. Adsorptive Recovery and Purification of Prodigiosin from Methanol/Water Solutions of Serratia Marcescens Fermentation Broth. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2014, 19, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qodah, Z.; Al-Zoubi, H.; Hudaib, B.; Omar, W.; Soleimani, M.; Abu-Romman, S.; Frontistis, Z. Sustainable vs. Conventional Approach for Olive Oil Wastewater Management: A Review of the State of the Art. Water 2022, 14, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, J.P. On the Comparison of Pseudo-First Order and Pseudo-Second Order Rate Laws in the Modeling of Adsorption Kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 300, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L.; Paul, K.K.; Jena, S. Adsorption Isotherm, Kinetics and Optimization Study by Box Behnken Design on Removal of Phenol from Coke Wastewater Using Banana Peel (Musa Sp.) Biosorbent. Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 2022, 56, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomakou, N.; Tsafrakidou, P.; Goula, A.M. Holistic Exploitation of Spent Coffee Ground: Use as Biosorbent for Olive Mill Wastewaters After Extraction of Its Phenolic Compounds. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahkarami, E.; Dehghan Monfared, A.; Silva, L.F.O.; Dotto, G.L. Lead Ferrite-Activated Carbon Magnetic Composite for Efficient Removal of Phenol from Aqueous Solutions: Synthesis, Characterization, and Adsorption Studies. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, M.; Selim, H.; Shahawy, A.E.L. Chitosan/MCM-48 Nanocomposite as a Potential Adsorbent for Removing Phenol from Aqueous Solution. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 23417–23430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yin, P.; Liu, X.; Qu, R. Design of an Effective Bifunctional Catalyst Organotriphosphonic Acid-Functionalized Ferric Alginate (ATMP-FA) and Optimization by Box-Behnken Model for Biodiesel Esterification Synthesis of Oleic Acid over ATMP-FA. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 173, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Huang, C.P.; Chen, C.W.; Bui, X.T.; Dong, C. Di Alkaline Modified Biochar Derived from Spent Coffee Ground for Removal of Tetracycline from Aqueous Solutions. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Meng, X.G.; Hu, C.W.; Du, J. Adsorption of Phenol, p-Chlorophenol and p-Nitrophenol onto Functional Chitosan. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Younesi, H.; Mahmoud, S.; Akbar, A.; Amini, M.; Daneshi, A. Application of Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Cadmium Biosorption in an Aqueous Solution by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 145, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.K.; Gupta, R.; Yadav, A.B.; Kumar, R. Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption on Treated Sawdust. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 89, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Variable | Coded Levels and Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| A: Temperature (°C) | 25 | 37.5 | 50 | |

| B: pH | 2 | 5 | 8 | |

| C: Adsorbent dosage (g/L) | XAD-4 resin, AC | 20 | 60 | 100 |

| CH-B | 2 | 5 | 8 | |

| Parameters | Raw OMWW | Filtered OMWW |

|---|---|---|

| pH (25 °C) | 5.1 | 5.03 |

| TCOD (gO2/L) | 260 ± 6 | 243 ± 2 |

| Total solids(g/L) | 145 ± 4 | 138 ± 2 |

| Total volatile solids (g/L) | 111 ± 3 | 104 ± 4 |

| Total phenolic compounds (g/L) | 8 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 |

| Element | AC | XAD-4 Resin | CH-B | AC | XAD-4 Resin | CH-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Adsorption | After Adsorption | |||||

| Weight Percent (w/w %) | ||||||

| C | 68.0 | 90.0 | 41.8 | 73.8 | 70.7 | 73.8 |

| N | 0.5 | - | 6.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| O | 30.6 | 1.0 | 46.5 | 22.7 | 26.4 | 22.7 |

| H | 0.9 | 9.0 | 5.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Model | Parameters | AC | XAD-4 Resin | CH-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFO (Equation (1)) | q1 (mg/g) | 84.1 ± 0.8 | 90.5 ± 3.1 | 210 ± 6 |

| K1 (×10−2) 1/min | 17 ± 2 | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| AIC | 29.7 | 35.9 | 42.1 | |

| BIC | 23.9 | 30.1 | 33.9 | |

| PSO (Equation (2)) | q2 (mg/g) | 89.6 ± 0.9 | 136.1 ± 0.3 | 258 ± 20 |

| K2 (×10−4 ) g/(mg.min) | 29.7 ± 2.5 | 7.6 ± 2.3 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.97 | |

| AIC | 16.1 | 39.2 | 48.6 | |

| BIC | 10.3 | 24.4 | 40.4 | |

| Elovich (Equation (3)) | a (g/mg) | 656 ± 592 | 1615.9 ± 7.6 | 1514.9 ± 5.9 |

| b (mg/(g min) | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.95 | |

| AIC | 31.8 | 44.6 | 52.9 | |

| BIC | 26.1 | 38.8 | 44.8 |

| Model | Parameters | AC | XAD-4 Resin | CH-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir (Equation (5)) | qm (mg/g) | 90.2 ± 2.1 | 104.8 ± 1.4 | 229.2 ± 17.3 |

| KL (×10−3) (L/mg) | 6.01 ± 0.8 | 2.11 ± 0.09 | 1.01 ± 0.32 | |

| RL | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.17 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | |

| AIC | 27.3 | 14.9 | 42.6 | |

| BIC | 14.6 | 2.3 | 30.02 | |

| Freundlich (Equation (7)) | KF (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n | 16.05 ± 1.32 | 2.36 ± 1.04 | 11.4 ± 2.6 |

| 1/n | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |

| AIC | 27.03 | 44.5 | 44.9 | |

| BIC | 1.8 | 19.3 | 19.7 | |

| Temkin (Equation (8)) | qT (mg/g) | 14.7 ± 0.1 | 39.3 ± 2.3 | 48.6 ± 5.04 |

| KT (×10−2) (L/g) | 15 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.09 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| AIC | −1.02 | 19.3 | 39.2 | |

| BIC | −13.6 | 6.7 | 26.6 |

| Adsorbent | Precursor/ Modification | Capacity | Initial Conc. of TPhC (C0, mg/L) | Dosage (g/L) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qexp (mg/g) | Qmax (mg/g) | |||||

| Chitosan Biosorbent (CH-B) | Shrimp Shells (Unmodified) | 196 | 229 | 3765 | 2 | This Study |

| Unmodified Insect Chitosan (H. illucens) | Hermetia illucens Waste | 416 | 269 | 0.5 | Elouali et al. [17] | |

| Chitosan | Lobster wastes (Unmodified, CS) | 83 | 8210 | 30 | Belhadj et al. [18] | |

| chitosan–epichlorohydrin bead (CS-ECH) | 232.6 | |||||

| Chitosan Nanocomposite | Commercial Unmodified Chitosan | 15 | 228 | 10 | Shmeis et al. [19] | |

| Nanocomposite (CKI-CP) | 19.8 | 2 | ||||

| Adsorbent | Reduced Equation | R2 | A.P | S.D | C.V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | Y1 = 58.92 − 1.61A − 11.54B + 16.27C + 4.39AB − 0.58AC + 0.88BC − 0.14A2 + 8.35B2 + 1.33C2 + 10.66A2B | 0.96 | 9.15 | 4.94 | 7.87 |

| XAD-4 resin | Y2 = 85.15 + 3.17A + 53.47B + 0.91C − 1.44AB − 0.02AC − 0.02BC + 0.028A2 − 4.88B2 − 0.0006C2 + 0.14AB2 | 0.94 | 9.39 | 3.63 | 5.68 |

| CH-B | Y3 = 63.38 + 2.20A + 0.4812B − 2.67C + 2.97AB + 0.77AC + 5.59BC − 20.01A2 + 7.08B2 − 0.46C2 + 3.35A2B − 1.48A2C | 0.99 | 37.77 | 1.25 | 2.22 |

| Adsorbent | Temperature (°C) | pH | Dosage (g/L) | TPhC Yield (%) | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 49 | 7 | 100 | 80 | 1 |

| XAD-4 resin | 25 | 4.93 | 100 | 79 | 0.98 |

| CH-B | 39 | 2 | 2 | 78 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hakim, C.; Carrère, H.; Essadek, A.; Terroufi, S.; Battimelli, A.; Escudie, R.; Harmand, J.; Neffa, M. Modeling and Optimization of Phenolic Compound Adsorption from Olive Wastewater Using XAD-4 Resin, Activated Carbon, and Chitosan Biosorbent. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031231

Hakim C, Carrère H, Essadek A, Terroufi S, Battimelli A, Escudie R, Harmand J, Neffa M. Modeling and Optimization of Phenolic Compound Adsorption from Olive Wastewater Using XAD-4 Resin, Activated Carbon, and Chitosan Biosorbent. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031231

Chicago/Turabian StyleHakim, Chaimaa, Hélène Carrère, Abdessadek Essadek, Soukaina Terroufi, Audrey Battimelli, Renaud Escudie, Jérôme Harmand, and Mounsef Neffa. 2026. "Modeling and Optimization of Phenolic Compound Adsorption from Olive Wastewater Using XAD-4 Resin, Activated Carbon, and Chitosan Biosorbent" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031231

APA StyleHakim, C., Carrère, H., Essadek, A., Terroufi, S., Battimelli, A., Escudie, R., Harmand, J., & Neffa, M. (2026). Modeling and Optimization of Phenolic Compound Adsorption from Olive Wastewater Using XAD-4 Resin, Activated Carbon, and Chitosan Biosorbent. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031231