When Demand Uncertainty Occurs in Emergency Supplies Allocation: A Robust DRL Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Reinforcement Learning

2.1.2. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm

2.2. Related Work

2.2.1. ESA Problems

2.2.2. Solutions of ESA Problems

2.2.3. Research Gap

3. System Description and Problem Formulation

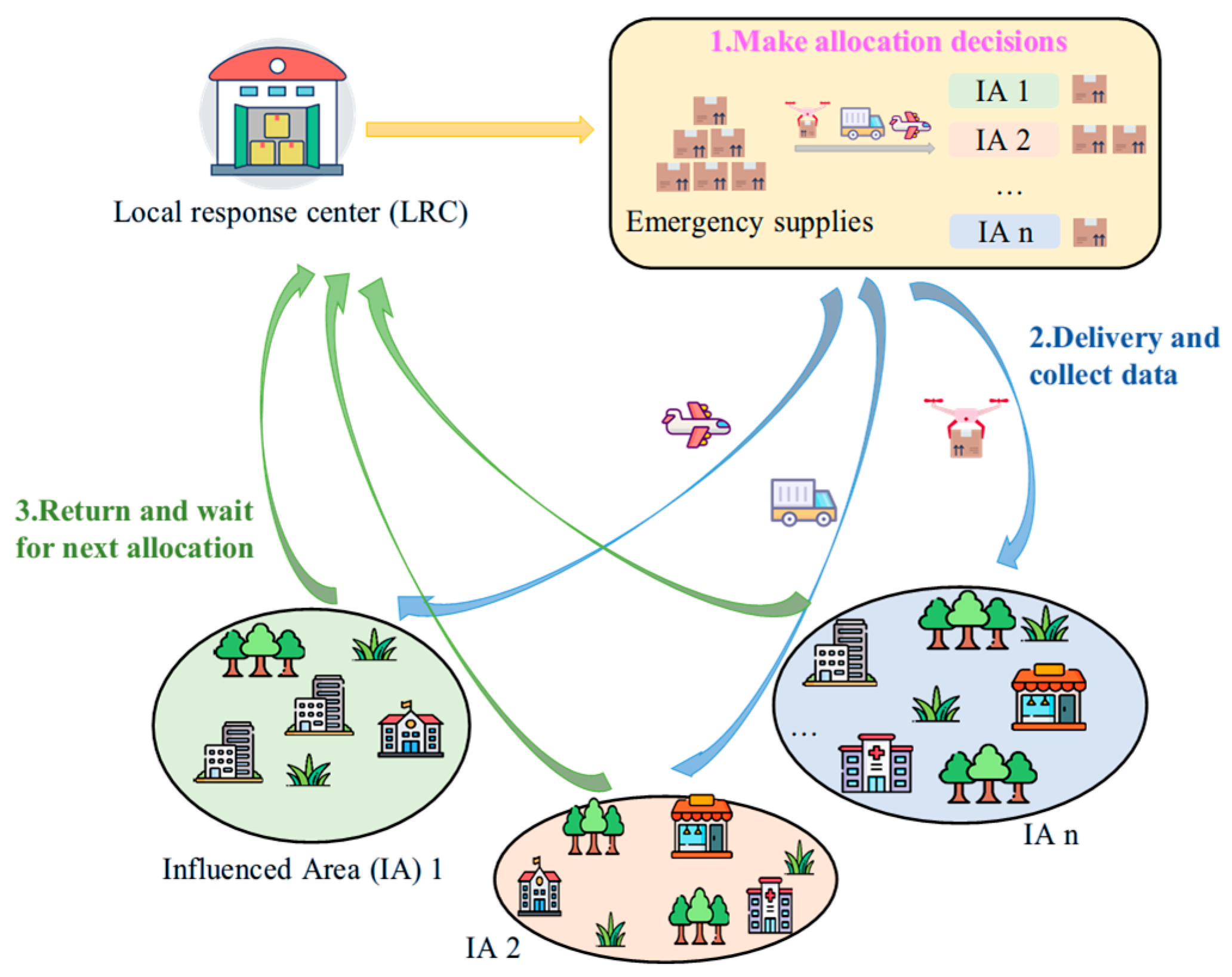

3.1. System Description

- (A1)

- The LRC can only make a nominal estimate of the demand in IAs based on historical data. This assumption is reasonable because it is difficult to estimate the exact demand with imperfect information.

- (A2)

- The LRC can allocate emergency supplies equal to its capacity within a single allocation period [32]. In addition, it is reasonable to assume that these emergency supplies are insufficient to meet demands in all IAs.

- (A3)

- Emergency supplies will be dispatched simultaneously at the beginning of each allocation period and are expected to be delivered by the end of the period [13].

- (A4)

- A fixed delivery cost is incurred based on the distance when delivering one unit of emergency supplies from the LRC to an IA.

3.2. Formulation as Mathematical Programming

3.3. Formulation as Two-Player Zero-Sum Markov Game

4. RESA_PPO Approach

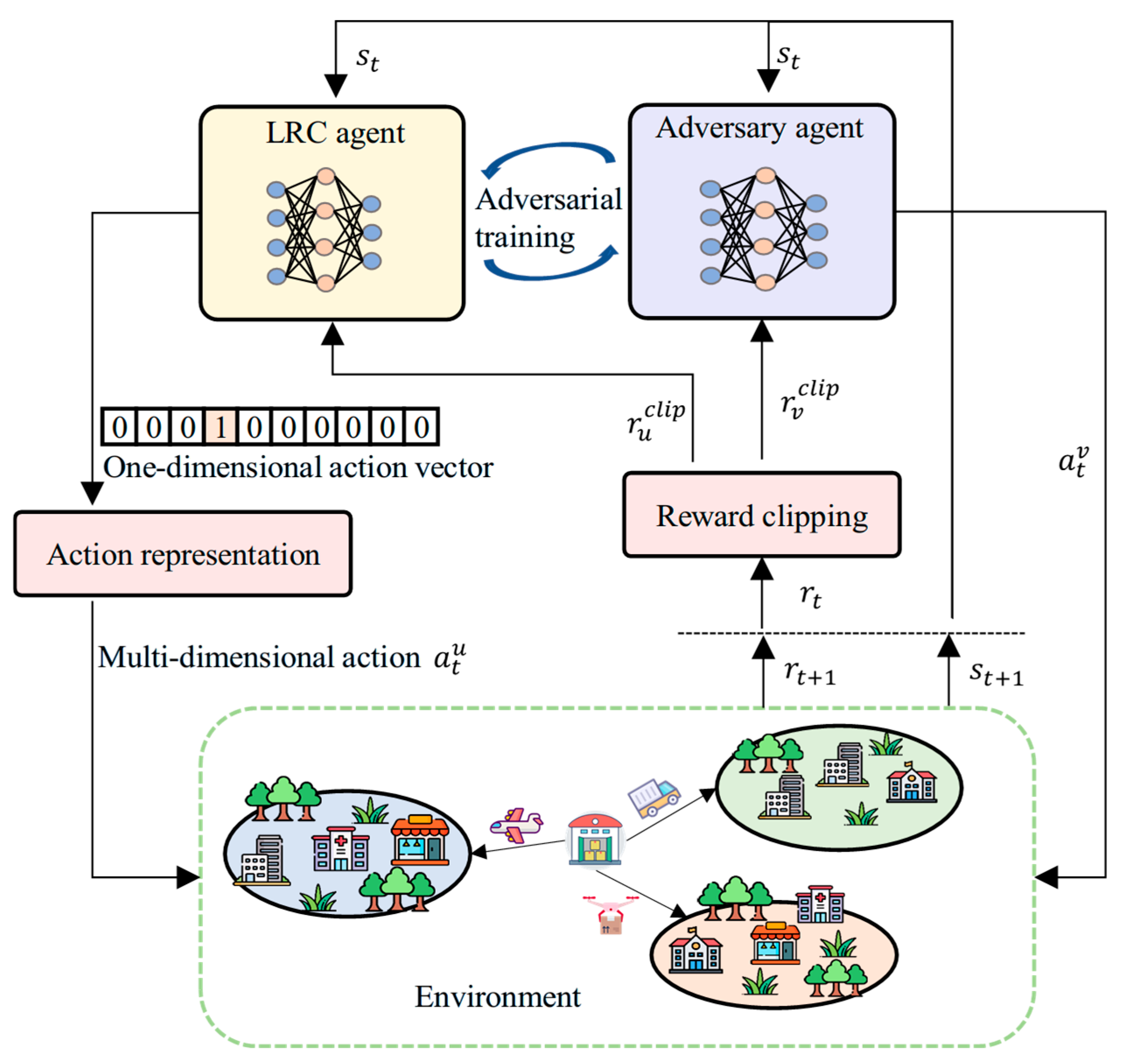

4.1. RESA Framework

4.1.1. Adversarial Training Method

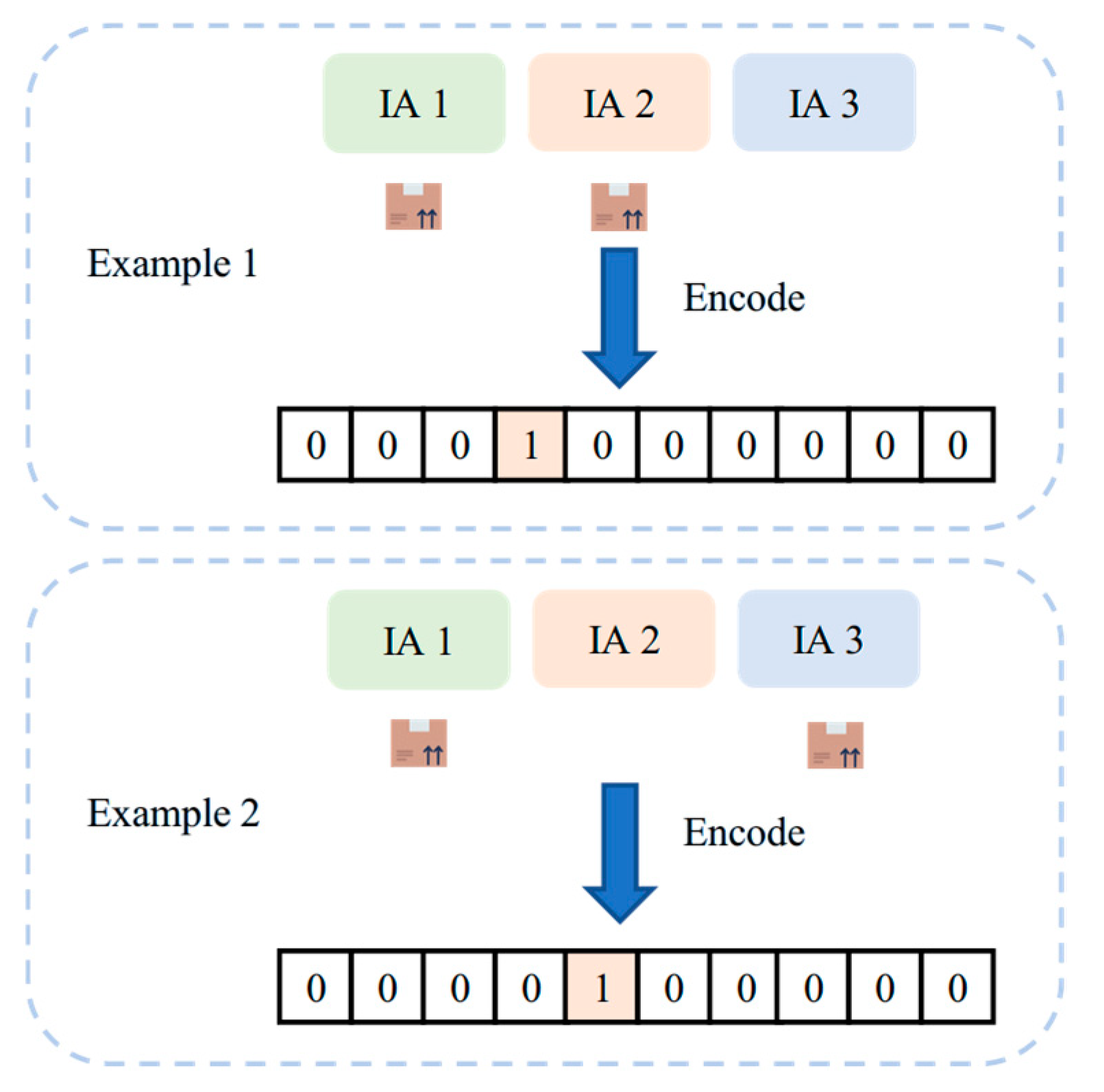

4.1.2. Combinatorial Action Representation Method

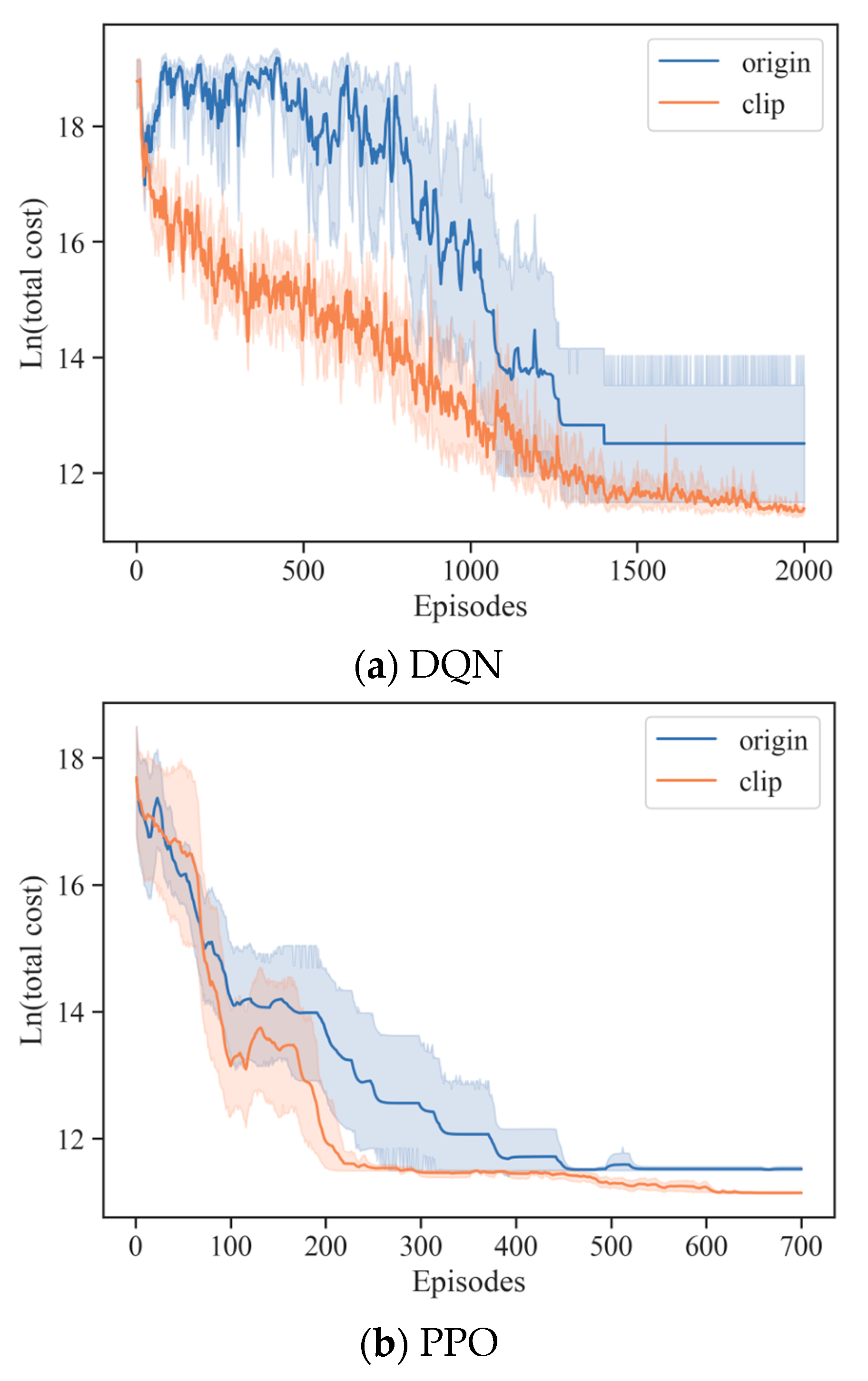

4.1.3. Reward Clipping Method

4.1.4. Summary

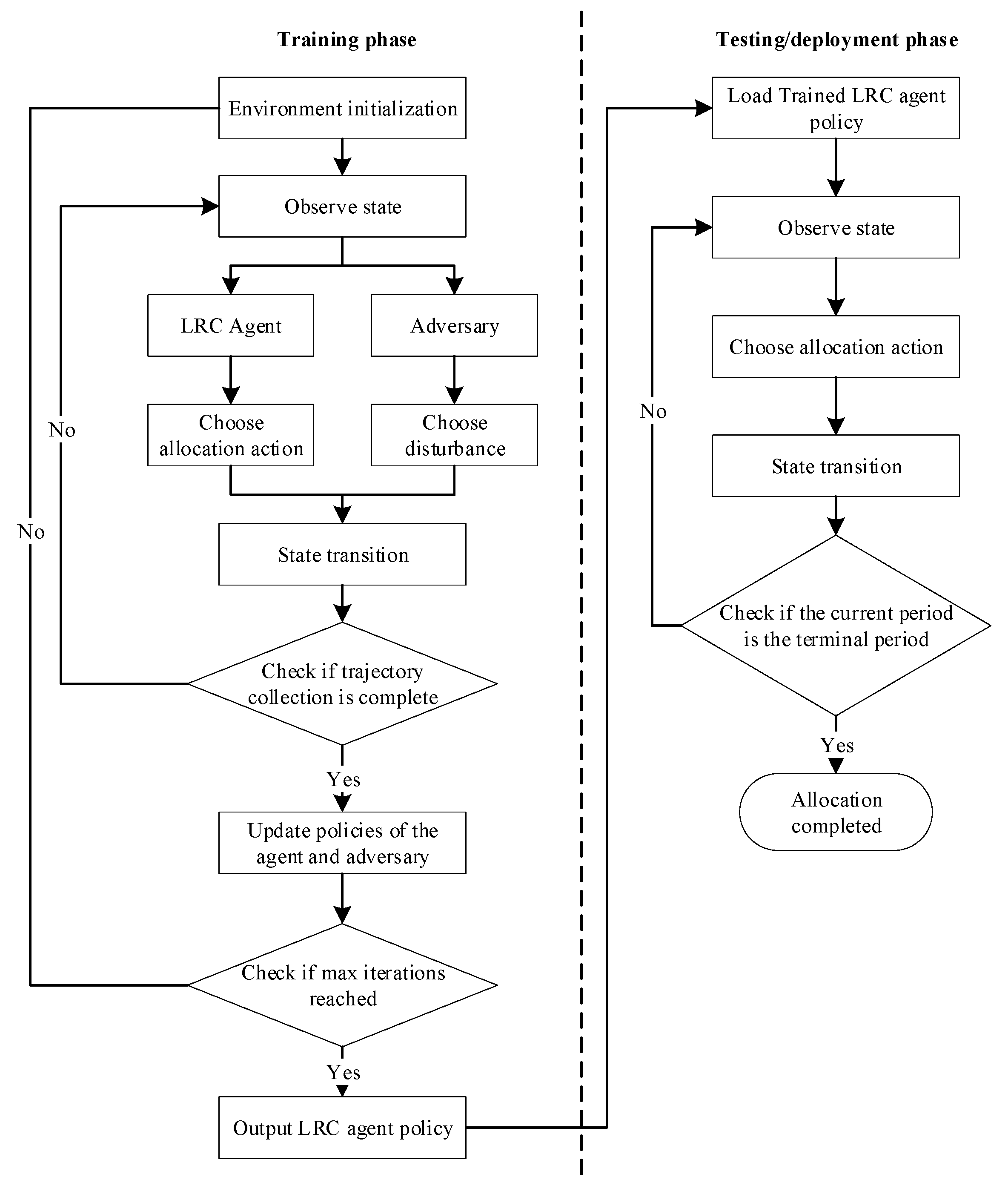

4.2. RESA_PPO Workflow

| Algorithm 1 RESA_PPO | |

| Input: Environment | |

| 1: | do: |

| 2: | |

| 3: | do: |

| 4: | do: |

| 5: | LRC chooses allocation action |

| 6: | Adversary chooses an IA to add disturbance |

| 7: | Take actions, and obtain |

| 8: | according to Equation (6) |

| 9: | |

| 10: | If done, reset the environment and continue |

| 11: | with gradient |

| 12: | End for |

| 13: | End for |

| 14: | |

| 15: | do: |

| 16: | do: |

| 17: | LRC chooses allocation action |

| 18: | Adversary chooses an IA to add disturbance |

| 19: | Take actions, and obtain |

| 20: | according to Equation (6) |

| 21: | |

| 22: | If done, reset the environment and continue |

| 23: | with gradient |

| 24: | End for |

| 25: | End for |

| 26: | End for |

5. Experimental Results and Discussions

5.1. Experiment Setting

5.2. Ablation Study

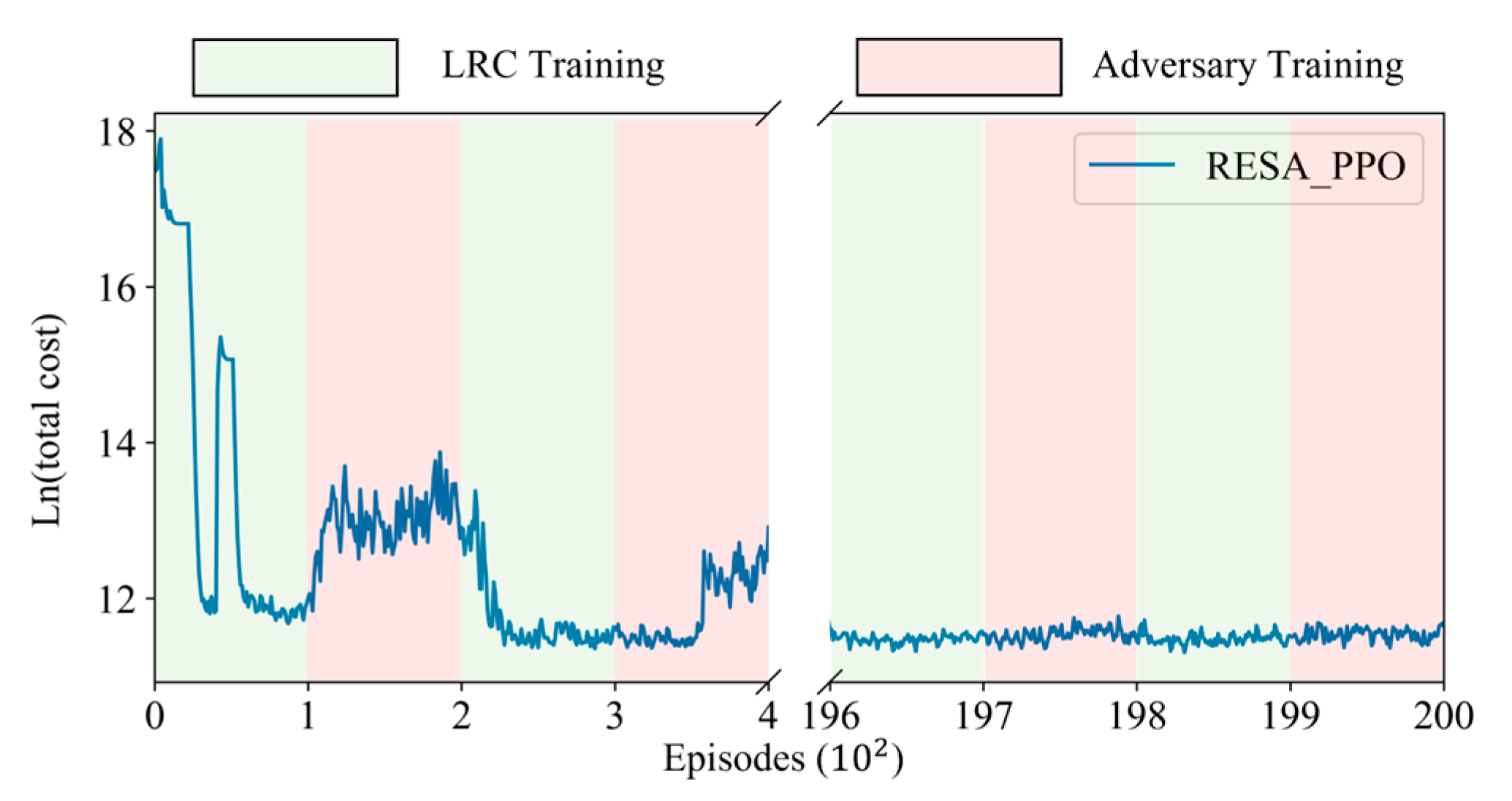

5.3. Convergence Analysis

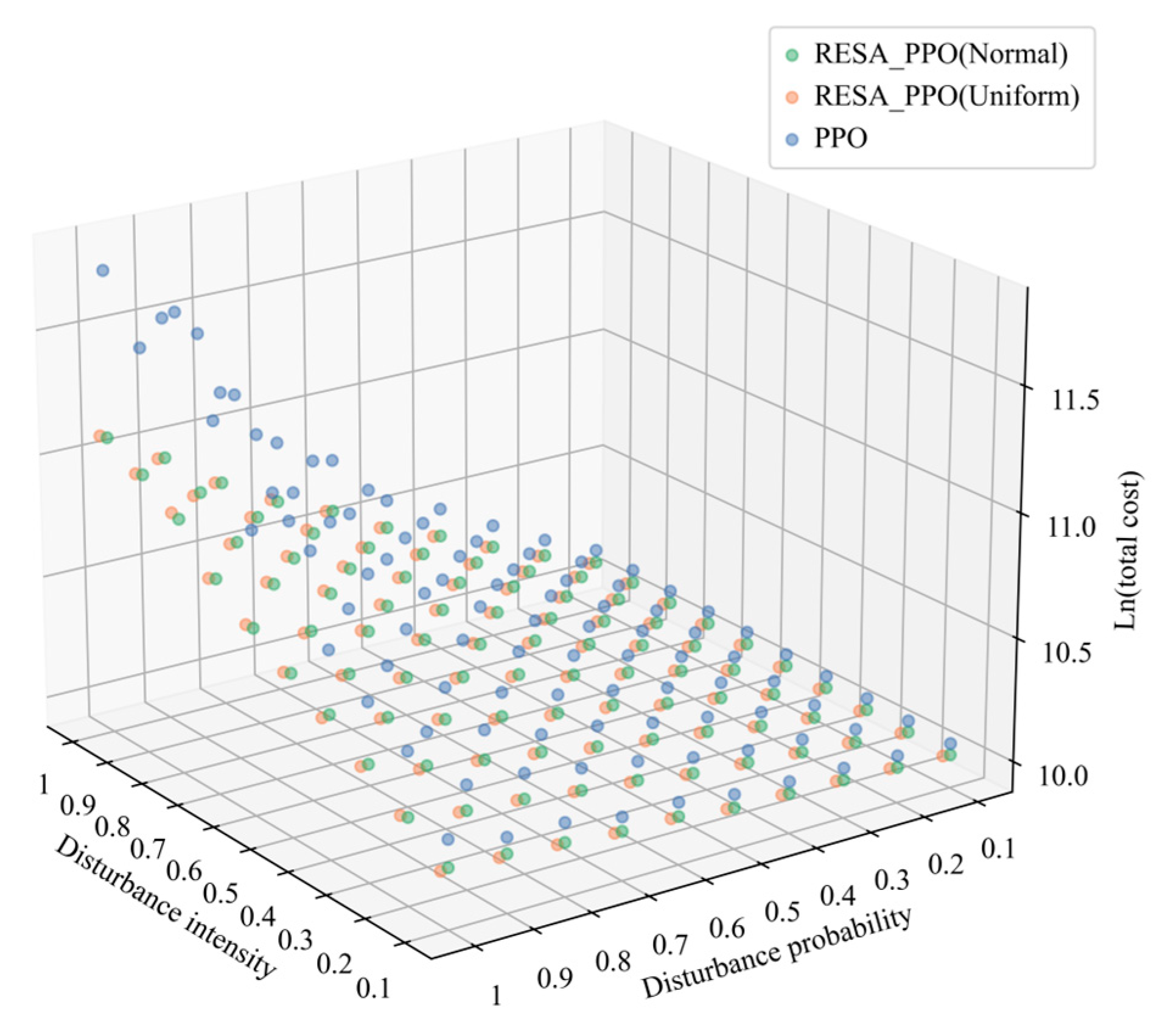

5.4. Comparison Analysis

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gralla, E.; Goentzel, J.; Fine, C. Assessing trade-offs among multiple objectives for humanitarian aid delivery using expert preferences. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, J.; Chu, F.; Wang, D. Distributionally robust multi-period humanitarian relief network design integrating facility location, supply inventory and allocation, and evacuation planning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Chen, W. Application of Distributionally Robust Optimization Markov Decision-Making Under Uncertainty in Scheduling of Multi-category Emergency Medical Materials. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Xie, J.; Jivaganesh, S.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M. Seeing sound, hearing sight: Uncovering modality bias and conflict of ai models in sound localization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Mao, R.; Zhao, S.; Lin, Q.; Jia, Y.; He, L.; Cambria, E. Exploring Cognitive and Aesthetic Causality for Multimodal Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis; IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Jia, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, S.; Chiang, F.; Cambria, E. From query to explanation: Uni-rag for multi-modal retrieval-augmented learning in stem. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.03868. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, S. Towards robust evaluation of stem education: Leveraging mllms in project-based learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17050. [Google Scholar]

- Plaksin, A.; Kalev, V. Zero-sum positional differential games as a framework for robust reinforcement learning: Deep Q-learning approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.02044. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Hsu, H.L.; Gao, Q.; Tarokh, V.; Pajic, M. Robust reinforcement learning through efficient adversarial herding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.07408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xuan, J.; Shi, T.; Li, Y.F. Multi-label domain adversarial reinforcement learning for unsupervised compound fault recognition. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 254, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Liu, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Lu, C. Short-term voltage stability emergency control strategy pre-formulation for massive operating scenarios via adversarial reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 389, 125751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Yang, H.; Shang, H. Reinforcement learning approach for resource allocation in humanitarian logistics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 173, 114663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chang, X.; Mišić, J.; Mišić, V.B.; Kang, H. DHL: Deep reinforcement learning-based approach for emergency supply distribution in humanitarian logistics. Peer–Peer Netw. Appl. 2022, 15, 2376–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Xu, F.; Chen, L.; Hui, P.; Li, Y. Hierarchical reinforcement learning for scarce medical resource allocation with imperfect information. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 14 August 2021; pp. 2955–2963. [Google Scholar]

- Shakya, A.K.; Pillai, G.; Chakrabarty, S. Reinforcement learning algorithms: A brief survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 2023, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jia, R.; Pan, H.; Cao, Y. A safe reinforcement learning-based charging strategy for electric vehicles in residential microgrid. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Sun, B.Q. Model of multi-period emergency material allocation for large-scale sudden natural disasters in humanitarian logistics: Efficiency, effectiveness and equity. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarosoğlu, G.; Özdamar, L.; Cevik, A. An interactive approach for hierarchical analysis of helicopter logistics in disaster relief operations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 140, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Allen, T.T.; Fry, M.J.; Kelton, W.D. The call for equity: Simulation optimization models to minimize the range of waiting times. IIE Trans. 2013, 45, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedrich, F.; Gehbauer, F.; Rickers, U. Optimized resource allocation for emergency response after earthquake disasters. Saf. Sci. 2000, 35, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, V.; Mecoli, M.; Nikoi, C.; Storchi, G. Multiperiod integrated routing and scheduling of World Food Programme cargo planes in Angola. Comput. Oper. Res. 2007, 34, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.M.; Vandenbussche, D.; Hermann, W. Routing for relief efforts. Transp. Sci. 2008, 42, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, P.; Zhou, M.; Gu, M. Design of multimodal hub-and-spoke transportation network for emergency relief under COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-heuristic approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 133, 109925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jiang, G.; Yao, X.; Chen, W.; Yue, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, Z. Allocation of emergency medical resources for epidemic diseases considering the heterogeneity of epidemic areas. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 992197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, J.B.; Chen, Y.H.; Lan, L.W. A novel model for quick response to disaster relief distribution. In Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Bangkok, Thailand, 21–24 September 2005; Volume 5, pp. 2454–2462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.P. Multiple-resource and multiple-depot emergency response problem considering secondary disasters. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 11066–11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, S. A novel min–max robust model for post-disaster relief kit assembly and distribution. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 214, 119198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Ye, C.; Peng, D. Multi-period dynamic multi-objective emergency material distribution model under uncertain demand. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Multiperiod optimal allocation of emergency resources in support of cross-regional disaster sustainable rescue. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 12, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, B. Multiperiod optimal emergency material allocation considering road network damage and risk under uncertain conditions. Oper. Res. 2022, 22, 2173–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, D.; Ignatius, J.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Dhamotharan, L. Distributionally robust multi-period location-allocation with multiple resources and capacity levels in humanitarian logistics. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lyu, M.; Sun, B. Emergency resource allocation considering the heterogeneity of affected areas during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, F.; Pizarro, C.; de Blas, C.S.; Ortuño, M.T.; Vitoriano, B. Uncertainty in humanitarian logistics for disaster management. A review. Decis. Aid Models Disaster Manag. Emergencies 2013, 7, 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Deng, W.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, F. A two-stage stochastic optimization for disaster rescue resource distribution considering multiple disasters. Eng. Optim. 2024, 56, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Han, C.; Hu, S. A two-stage chance constrained stochastic programming model for emergency supply distribution considering dynamic uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 179, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Liu, Y.; Tang, O.; Gao, X. A fuzzy bi-level optimization model for multi-period post-disaster relief distribution in sustainable humanitarian supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y. A bi-objective robust optimization model for disaster response planning under uncertainties. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 155, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, K.; Yang, L.; Gao, Z. Distributionally robust chance-constrained programming for multi-period emergency resource allocation and vehicle routing in disaster response operations. Omega 2023, 120, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bai, J.; Wu, D. Medical supplies scheduling in major public health emergencies. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 154, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliakbari, A.; Rashidi Komijan, A.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Najafi, E. A new robust optimization model for relief logistics planning under uncertainty: A real-case study. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 3883–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.M.; Ortuño, M.T.; Tirado, G. A new ant colony-based methodology for disaster relief. Mathematics 2020, 8, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, P.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Panneerselvam, J. Design and Application of Vague Set Theory and Adaptive Grid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm in Resource Scheduling Optimization. J. Grid Comput. 2023, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenbergen, R.; Mes, M.; Van Heeswijk, W. Reinforcement learning for humanitarian relief distribution with trucks and UAVs under travel time uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 157, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraci, G.; Rizzo, S.A.; Schembra, G. Green Edge Intelligence for Smart Management of a FANET in Disaster-Recovery Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 3819–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Miao, L. Novel methods for resource allocation in humanitarian logistics considering human suffering. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 119, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, D. Prepositioning network design for humanitarian relief purposes under correlated demand uncertainty. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Liu, Q.; Yu, G. Robustifying the resource-constrained project scheduling against uncertain durations. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Davidson, J.; Sukthankar, R.; Gupta, A. Robust adversarial reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 2817–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Patek, S.D. Stochastic and Shortest Path Games: Theory and Algorithms. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, D. Online minimax Q network learning for two-player zero-sum Markov games. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 33, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Luo, H.; Wei, C.Y.; Zheng, W. Uncoupled and convergent learning in two-player zero-sum markov games. In 2023 Workshop The Many Facets of Preference-Based Learning; ICML: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Reddi, A.; Tölle, M.; Peters, J.; Chalvatzaki, G.; D’Eramo, C. Robust adversarial reinforcement learning via bounded rationality curricula. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.01642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| The total number of IAs | |

| The total number of ESA periods | |

| The length of each allocation period | |

| The capacity of the local response center | |

| The delivery cost of delivering one unit of emergency supplies from the LRC to the IA | |

| The estimated demand for emergency supplies in IA | |

| The disturbance in the demand of IA in allocation period | |

| , | The parameters of the starting-state-based deprivation cost (S2DC) |

| The weights of the three objectives in the objective function | |

| The decision to allocate resources to the IA in allocation period | |

| The state of the IA in allocation period | |

| The factor to control the intensity of demand disturbances |

| Ref. | Objectives | Planning Horizon | Type | Model | Solution Approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Effectiveness | Equity | Single | Multiple | Deterministic | Uncertain | |||

| [12] (2021) | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x | MDP | RL |

| [13] (2022) | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x | MDP | DRL |

| [18] (2023) | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x | Mixed integer programming | Exact |

| [28] (2023) | √ | √ | x | √ | x | x | √ | Robust optimization | Exact |

| [29] (2023) | √ | √ | x | x | √ | x | √ | Fuzzy optimization | Metaheuristic |

| [33] (2024) | √ | x | √ | x | √ | √ | x | MINLP | Exact |

| Ours | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | x | √ | TZMG | DRL |

| Parameters | IA 1 | IA 2 | IA 3 | IA 4 | IA 5 | IA 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ($) | 480 | 710 | 400 | 337 | 610 | 540 |

| (Unit) | 1.73 | 1.35 | 1.82 | 1.6 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Parameters of DQN-Based Approaches | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Greedy factor | 0.5 |

| The size of the memory pool | 1,000,000 |

| Batch size | 256 |

| The interval for updating the target network | 200 (steps) |

| Number of steps per episode | 6 |

| Number of episodes per iteration | 2000 |

| Parameters of PPO-based Approaches | |

| Learning rates of actor network and critic network | 0.0001 |

| Clip factor | 0.2 |

| Number of epochs | 15 |

| Maximum times steps per episode | 500 |

| Number of episodes per iteration | 100 |

| Shared hyperparameters | |

| Number of iterations | 100 |

| Discount factor | 0.9 |

| Number of hidden layers of DNNs | 2 |

| Hidden layer size | 64 |

| Training disturbance intensity factor | 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 |

| Category | Method | Information Availability | Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Bound | Optimal | Current State, Demand across all periods | Gurobi |

| Heuristics | GA | Current State, Current Demand | Greedy Selection |

| RA | Current State | Rule-based | |

| Standard RL | DQN | Current State | Gradient optimization |

| PPO | Current State | Gradient optimization | |

| Robust RL | RESA_DQN | Current State | Gradient optimization |

| RESA_PPO | Current State | Gradient optimization |

| Optimal | DQN | PPO | RESA_DQN | RESA_PPO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 22,077.60 | 23,004.45 | 23,340.41 | 22,307.80 | 22,624.51 | 22,126.40 | 22,748.12 |

| 0.5 | 22,768.01 | 24,874.67 | 24,153.36 | 23,198.12 | 23,789.29 | 22,831.06 | 23,466.43 | |

| 1.0 | 23,675.62 | 26,106.65 | 25,126.09 | 24,237.34 | 24,684.92 | 23,712.20 | 24,390.38 | |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 22,438.21 | 23,374.70 | 23,790.65 | 22,579.58 | 22,995.94 | 22,482.48 | 23,089.99 |

| 0.5 | 24,775.94 | 26,987.43 | 26,693.97 | 25,429.77 | 25,935.87 | 25,047.78 | 25,779.32 | |

| 1.0 | 27,994.24 | 30,404.30 | 30,800.42 | 29,030.53 | 29,287.91 | 28,429.65 | 29,332.43 | |

| 0.5 | 0.1 | 22,808.34 | 23,962.18 | 24,600.46 | 23,247.82 | 23,643.88 | 23,059.83 | 23,749.30 |

| 0.5 | 27,262.65 | 30,459.01 | 31,753.89 | 28,793.31 | 29,190.73 | 28,337.23 | 29,242.92 | |

| 1.0 | 33,203.29 | 37,113.87 | 39,927.27 | 35,651.37 | 35,573.18 | 34,527.71 | 35,827.37 | |

| 0.9 | 0.1 | 23,968.62 | 25,227.27 | 26,451.41 | 24,504.35 | 24,930.79 | 24,248.88 | 24,921.58 |

| 0.5 | 32,583.77 | 42,067.32 | 46,463.51 | 39,376.88 | 39,186.01 | 35,990.21 | 37,259.94 | |

| 1.0 | 49,521.07 | 92,612.60 | 107,427.61 | 105,941.83 | 73,570.86 | 59,668.16 | 63,047.81 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Fan, J.; Zhu, W.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Chang, X. When Demand Uncertainty Occurs in Emergency Supplies Allocation: A Robust DRL Approach. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020581

Wang W, Fan J, Zhu W, Cai Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, Yao Y, Chang X. When Demand Uncertainty Occurs in Emergency Supplies Allocation: A Robust DRL Approach. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020581

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Weimeng, Junchao Fan, Weiqiao Zhu, Yujing Cai, Yang Yang, Xuanming Zhang, Yingying Yao, and Xiaolin Chang. 2026. "When Demand Uncertainty Occurs in Emergency Supplies Allocation: A Robust DRL Approach" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020581

APA StyleWang, W., Fan, J., Zhu, W., Cai, Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, X., Yao, Y., & Chang, X. (2026). When Demand Uncertainty Occurs in Emergency Supplies Allocation: A Robust DRL Approach. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020581