Deep Learning for Real-Time Detection of Brassicogethes aeneus in Oilseed Rape Using the YOLOv4 Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

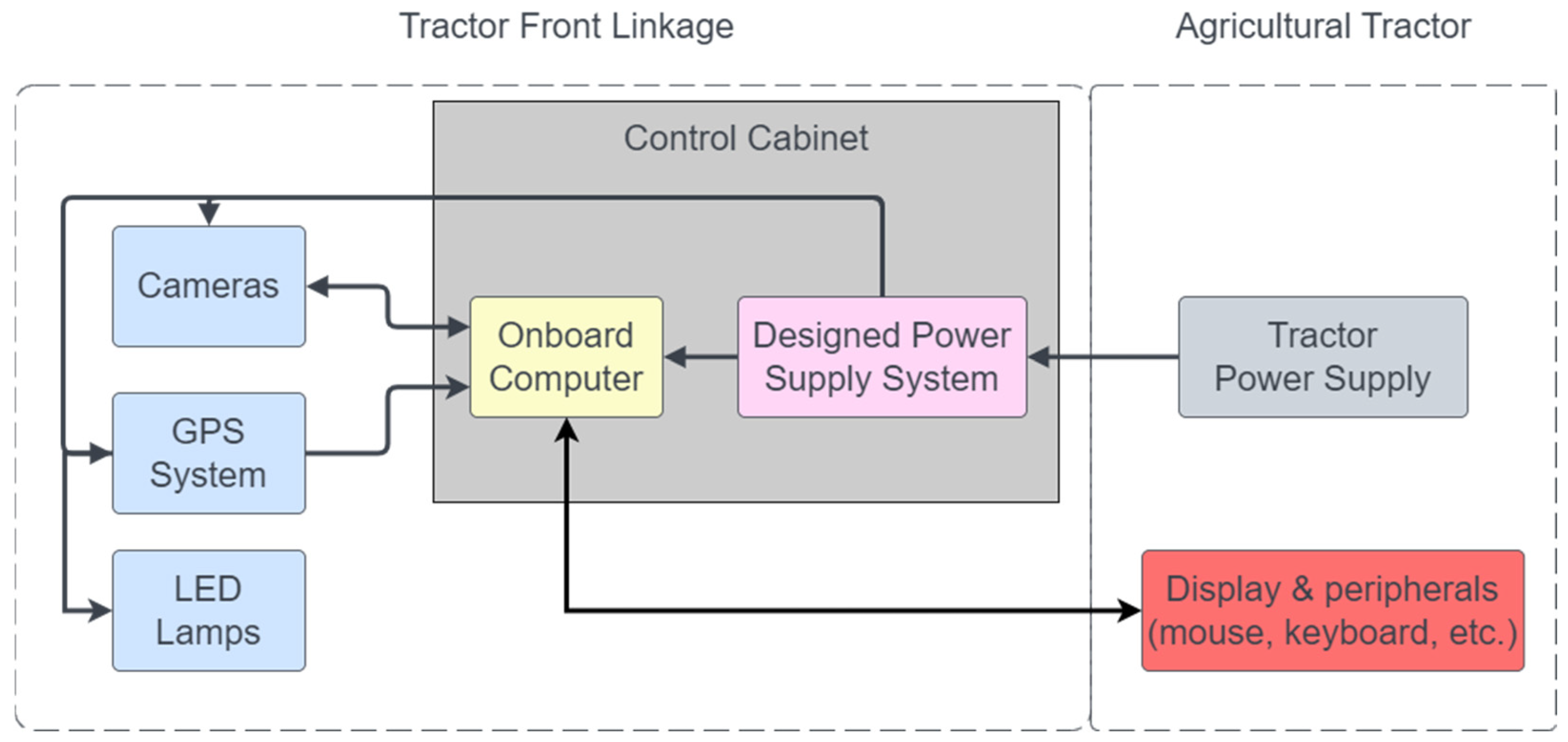

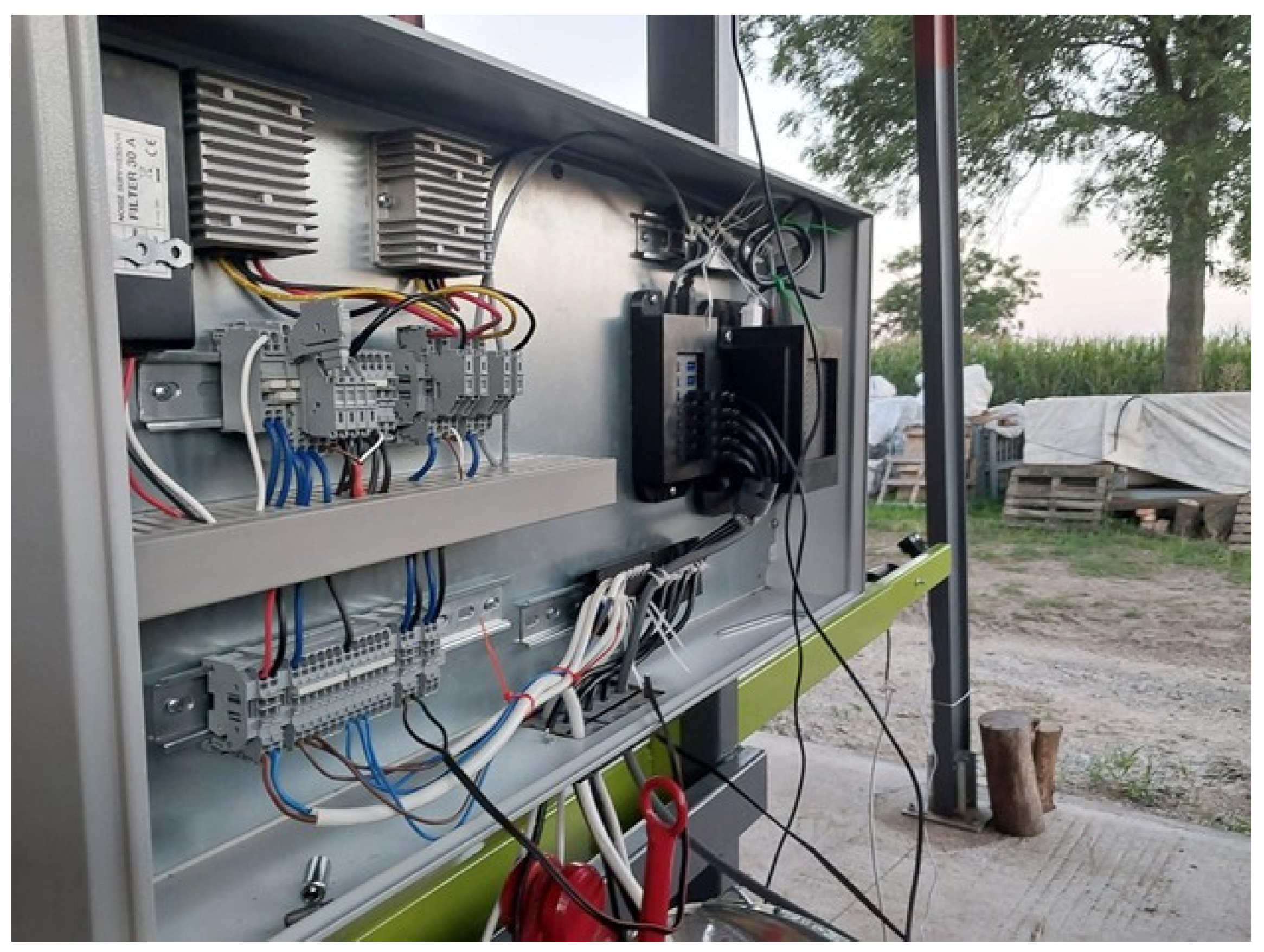

2.1. System Architecture and Hardware Configuration

- An onboard Jetson Orin AGX computer (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DC power supply housed in a protective enclosure.

- Four GoPro Hero 11 Black cameras (GoPro, Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) equipped with integrated GPS.

- Input/output peripherals (LCD display, mouse, keyboard).

- A 12 VDC power connection from the tractor.

2.2. Field Data Acquisition and Site Description

2.3. Dataset Preparation and Annotation

2.4. Object Detection Model and Training Configuration

2.5. Model Evaluation and Ground Truth Correlation

- Effective detection of small objects: Given the pests’ minimal size, often only a few pixels wide.

- Fast object recognition: Required for near-real-time inference on a mobile, tractor-mounted computer.

- Moderate accuracy: Correlation between detected and actual pest count is more critical than individual detection errors for guiding site-specific pesticide application.

3. Results

3.1. Detection Accuracy and Performance Metrics

3.2. Real-Time Inference and Field Testing

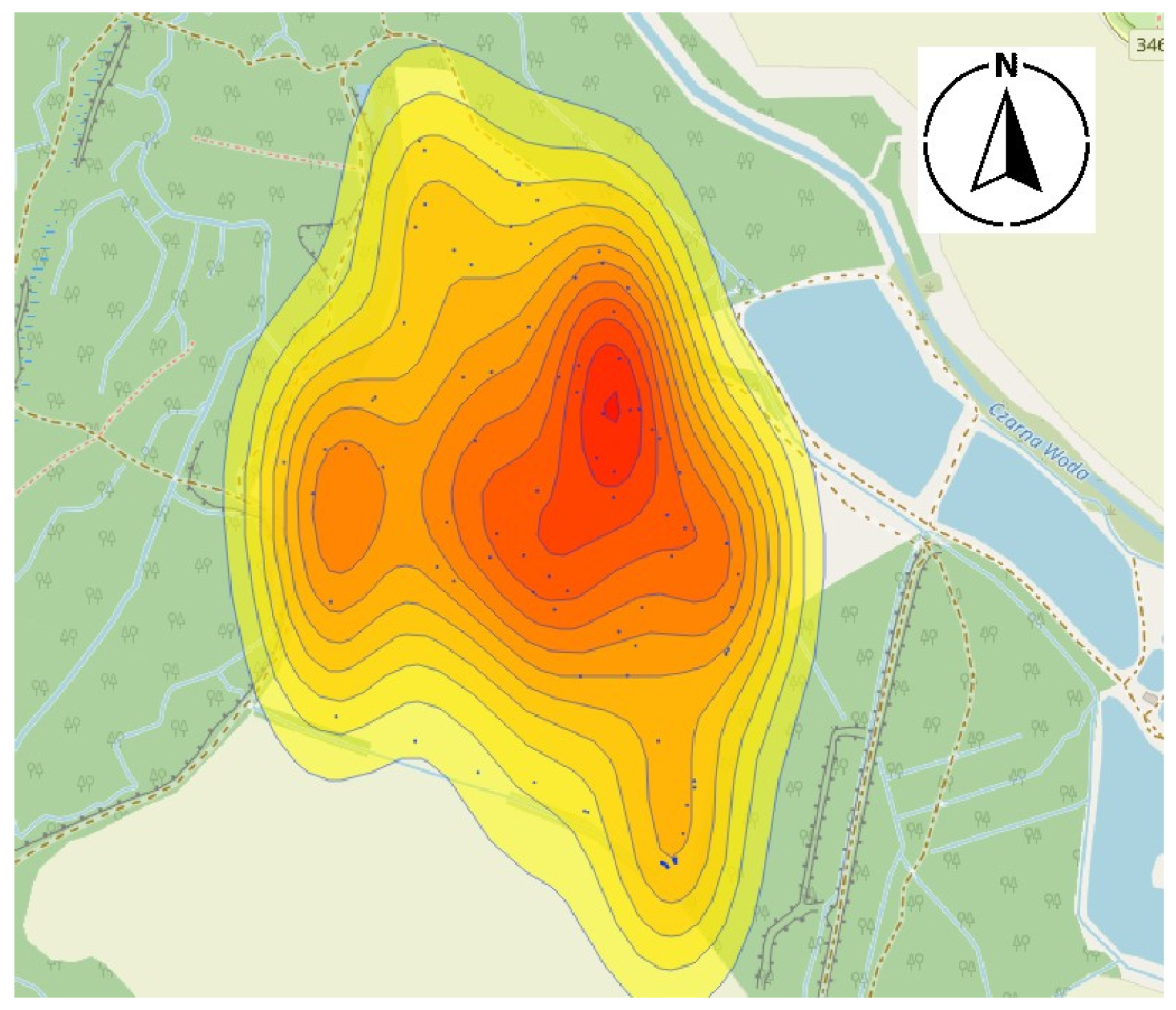

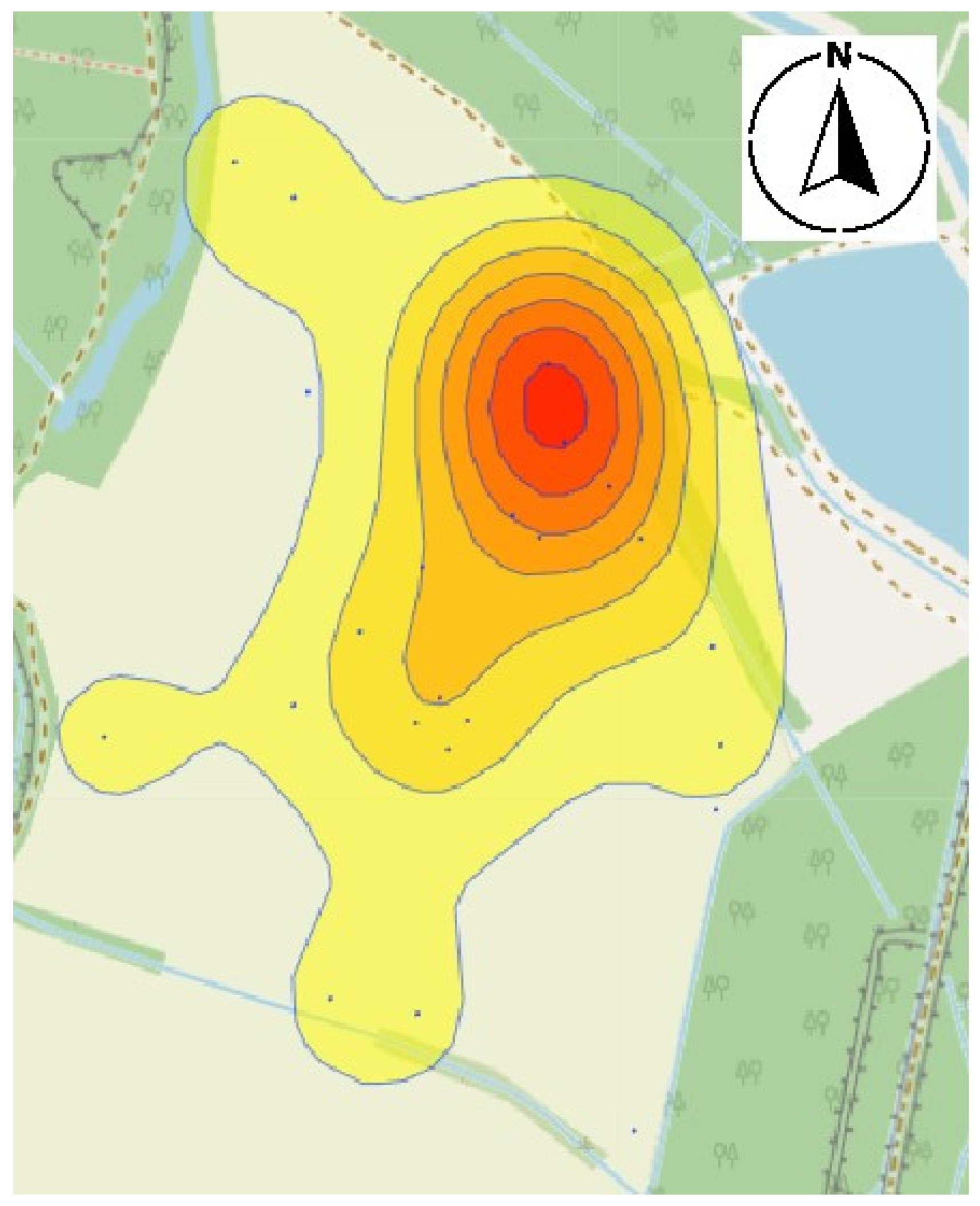

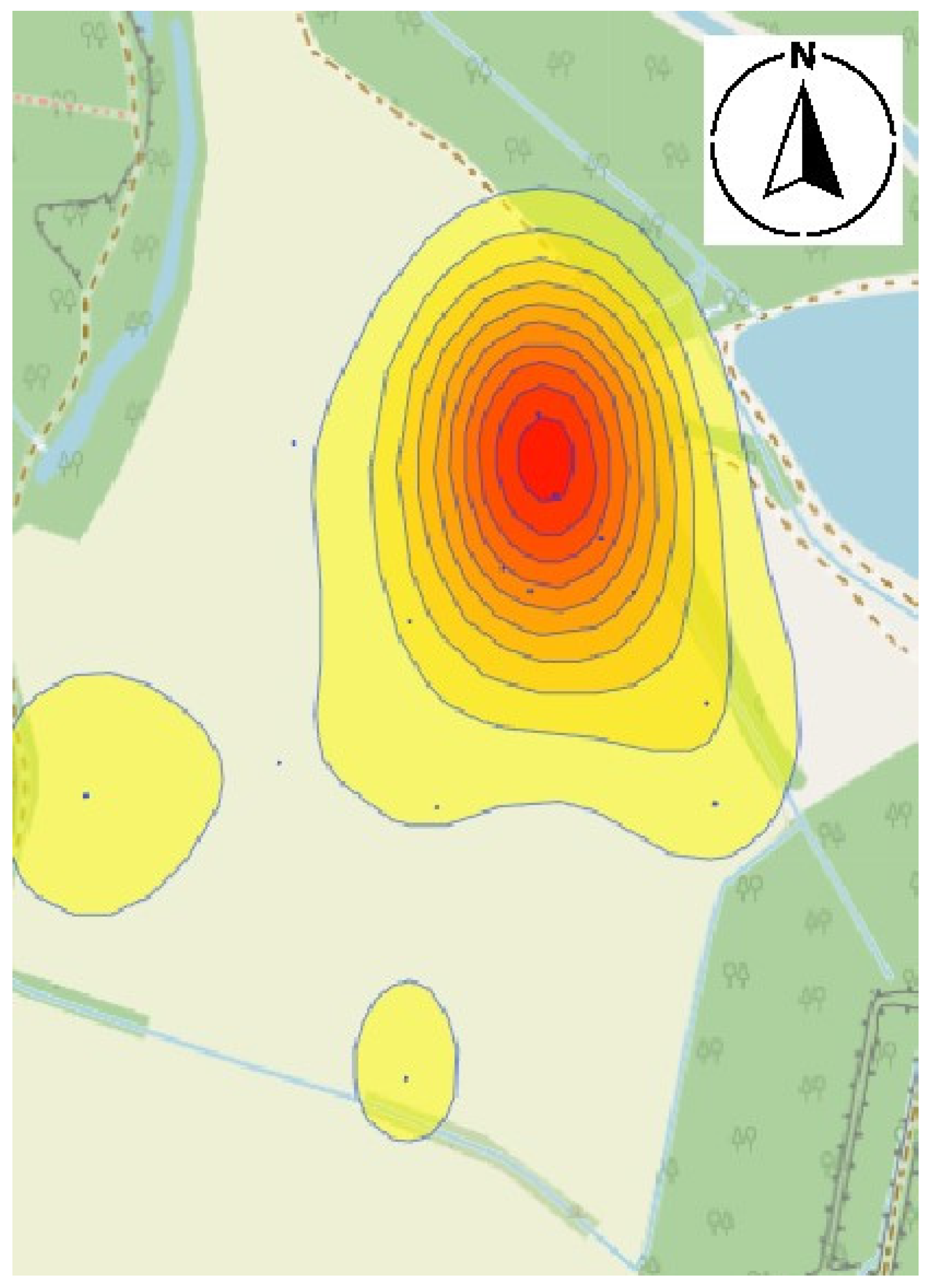

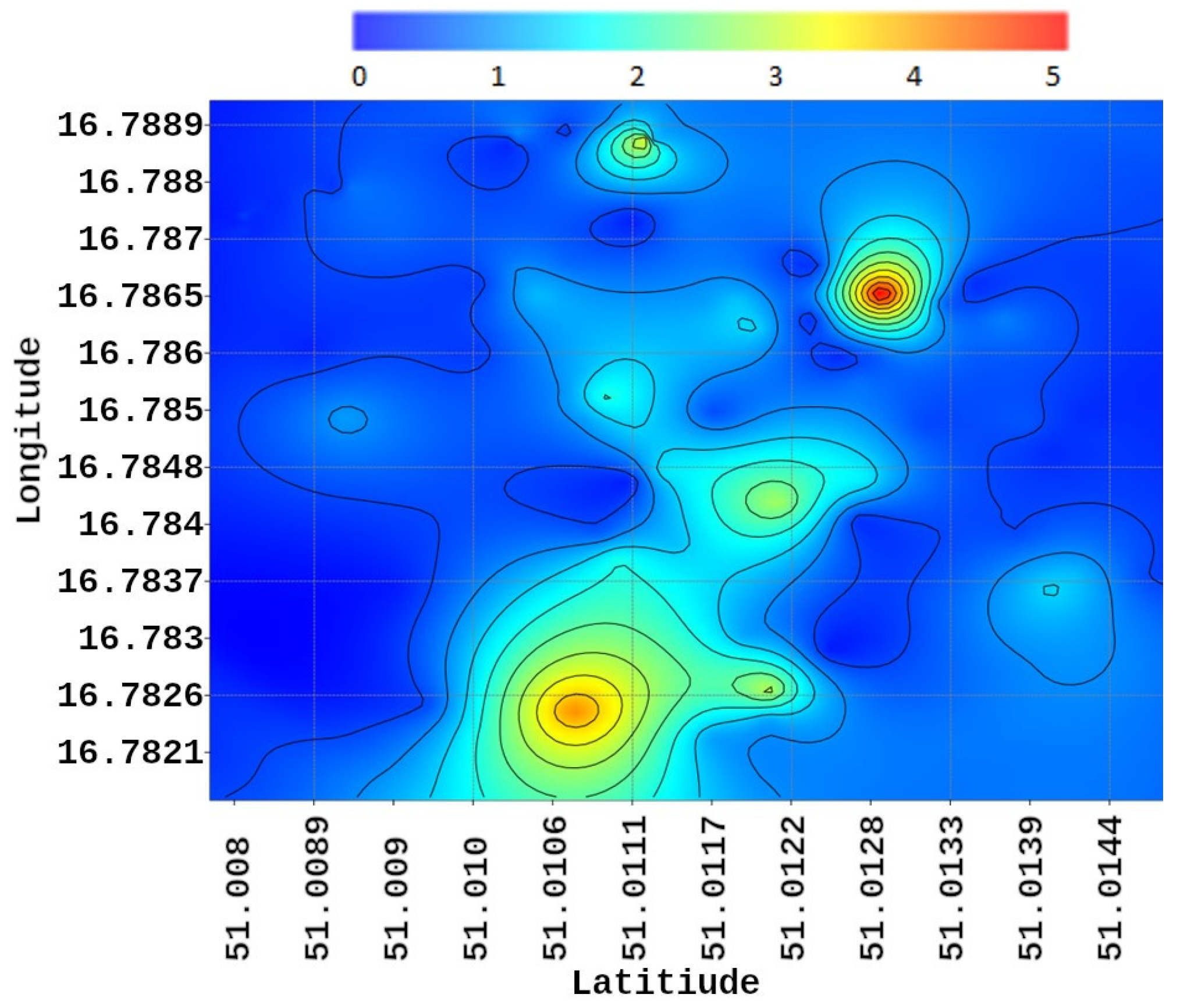

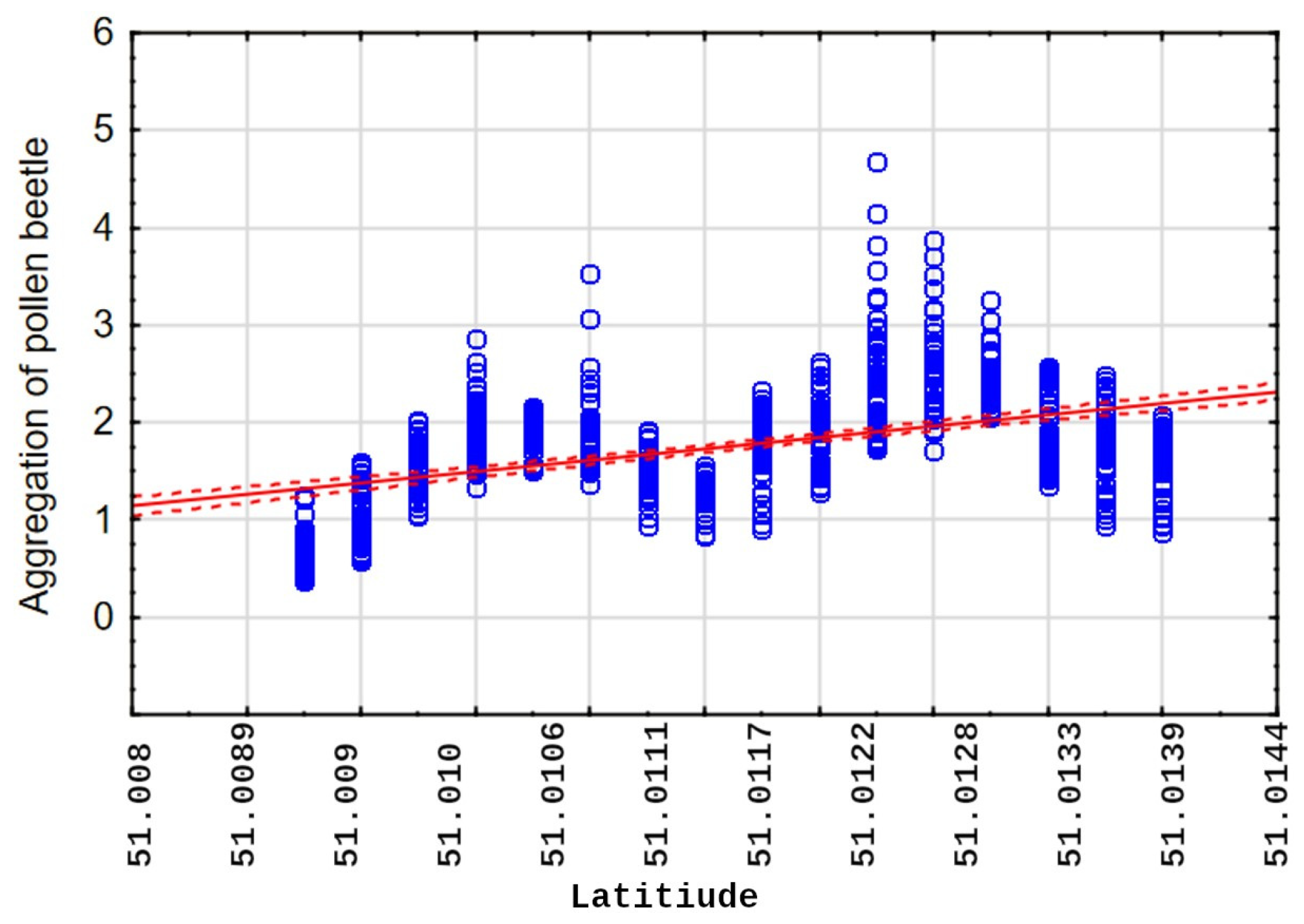

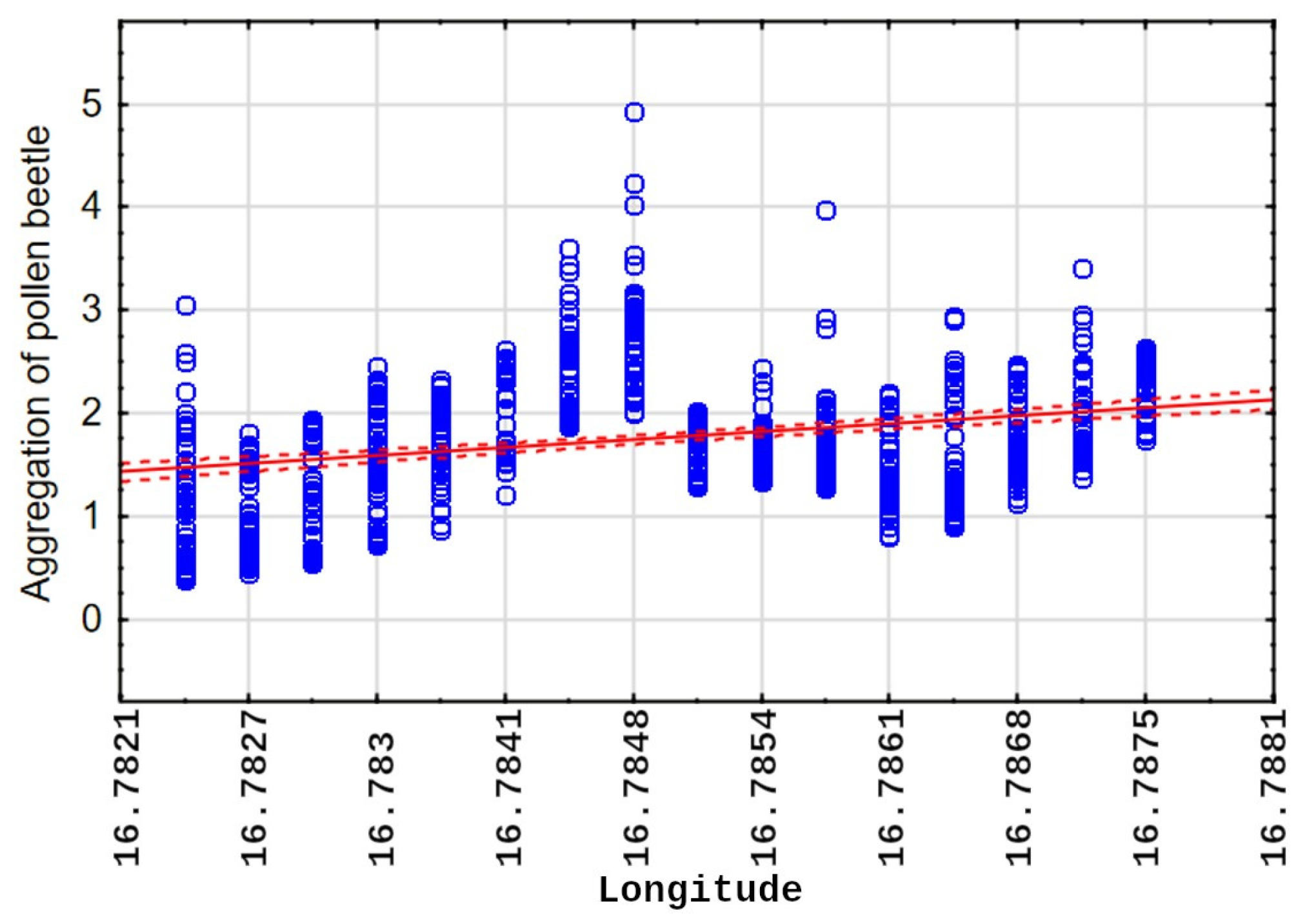

3.3. Derivation of Harmfulness Thresholds and Mapping

4. Discussion

4.1. Pest Migration and Distribution Patterns

4.2. Spatial Correlation and Environmental Proxies

4.3. Technical Optimization and System Scalability

4.4. Economic and Environmental Impact

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Population Review. 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Cook, S.; Jędryczka, M. Integrated pest control in oilseed crops—New advances from the rapeseed research community. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 2217–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausmann, J. Challenges for integrated pest management of Dasineurabrassicae in oilseed rape. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2021, 15, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauchline, A.L.; Cook, S.M.; Powell, W.; Chapman, J.W.; Osborne, J.L. Migratory flight behaviour of the pollen beetle Meligethes aeneus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bick, E.; Sigsgaard, L.; Torrance, M.T.; Helmreich, S.; Still, L.; Beck, B.; El Rashid, R.; Lemmich, J.; Nikolajsen, T.; Cook, S.M. Dynamics of pollen beetle (Brassicogethes aeneus) immigration and colonization of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) in Europe. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, U.; Redlich, S.; Zhang, J.; Benjamin, C.; Englmeier, J.; Ganuza, C.; Haensel, M.; Riebl, R.; Rojas-Botero, S.; Tobisch, C.; et al. Earlier flowering of winter oilseed rape compensates for higher pest pressure in warmer climates. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaller, J.G.; Moser, D.; Drapela, T.; Schmöger, C.; Frank, T. Effect of within-field and landscape factors on insect damage in winter oilseed rape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 123, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhel, A.S.; Barbu, C.M.; Franck, P.; Roger-Estrade, J.; Butier, A.; Bazot, M.; Valantin-Morison, M. Characterization of the pollen beetle, Brassicogethes aeneus, dispersal from woodlands to winter oilseed rape fields. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.H. The major insect pests of oilseed Rape in Europe and their management: An overview. In Biocontrol-Based Integrated Management of Oilseed Rape Pests, 1st ed.; Williams, I.H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ramos, P.A.; Cook, S.M.; Mauchline, A.L. How contradictory EU policies led to the development of a pest: The story of oilseed rape and the cabbage stem flea beetle. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Breeze, T.; Bailey, A.; Garthwaite, D.; Harrington, R.; Potts, S.G. Arthropod pest control for UK oilseed rape—Comparing insecticide efficacies, side effects and alternatives. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nils, C.; Brandes, M.; Ulber, B.; Heimbach, U. Effect of immigration time and beetle density on development of the cabbage stem flea beetle, (Psylliodes chrysocephala L.) and damage potential in winter oilseed rape. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Bohat, V.K.; Ansari, M.D.; Sinha, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Garg, D. A convulation neural network based approach to detect disease in corn crop. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing, IACC, Tiruchirappalli, India, 13–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, L.M. Economic damage threshold model for pollen beetles (Meligethes aeneus F.) in spring oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) crops. Crop Prot. 2024, 23, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratwal, A.; Witaszak, W.; Trzciński, P.; Baran, M.; Bocianowski, J. Analysis of winter oilseed rape damages caused by Brassicogethes aeneus (Fabricius, 1775) in various regions of Poland, in 2009–2019. Prog. Plant Prot. 2022, 62, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrówczyński, M.; Pruszyński, G.; Walczak, F. Monitoring i progi szkodliwości najważniejszych szkodników rzepaku. Prog. Plant Prot. 2013, 53, 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292315247_Integrowana_Ochrona_Upraw_Rolniczych_Tom_II_Zastosowanie_Integrowanej_Ochrony (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Witzgall, P.; Kirsch, P.; Cork, A. Sex pheromones and their impact on pest management. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwood, T.R.E.; Henderson, P.A. Ecological Methods, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2000; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260051655_Ecological_Methods_3rd_edition (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Walczak, F. Monitoring agrofagów dla potrzeb integrowanej ochrony roślin uprawnych. Fragm. Agron. 2010, 27, 147–154. Available online: https://pta.up.poznan.pl/pdf/2010/FA%2027(4)%202010%20Walczak.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Albanese, A.; Nardello, M.; Brunelli, D. Automated pest detection with DNN on the edge for precision agriculture. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, H.; Horst, L.; Wallhead, M.; Reding, M.; Fulcher, A. Management of pest insects and plant diseases in fruit and nursery production with laser-guided variable-rate sprayers. HortScience 2020, 56, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karise, R.; Eneli Viik, E.; Mänd, M. Impact of alpha-cypermethrin on honey bees foraging on spring oilseed rape (Brassica napus) flowers in field conditions. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, R.; Catal, C.; Kassahun, A. Plant disease detection using drones in precision agriculture. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1663–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, C.; Xiao, D.; Huang, Q. Automatic monitoring of flying vegetable insect pests using an RGB camera and YOLO-SIP detector. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkeby, C.; Rydhmer, K.; Cook, S.M.; Strand, A.; Torrance, M.T.; Swain, J.L.; Prangsma, J.; Johnen, A.; Jensen, M.; Brydegaard, M.; et al. Advances in automatic identification of flying insects using optical sensors and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.A.; Caceres Campana, J.W. Identification of pathogens in corn using near-infrared UAV imagery and deep learning. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 783–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, O.-H. Machine learning algorithms for early detection of legume crop disease. Legume Res. 2024, 47, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.L. Iot-based agriculture and smart farming: Machine learning applications: A commentary. Open Access J. Data Sci. Artif. Intell. 2024, 2, 000110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Qian, M. Small-target weed-detection model based on YOLO-V4 with improved backbone and neck structures. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 2149–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Bais, A. Deepveg: Deep learning model for segmentation of weed, canola, and canola flea beetle damage. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119367–119380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, B.; Passi, K.; Jain, C.K. Applications of artificial intelligence based technologies in weed and pest detection. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 18, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Dong, W.; Li, R.; Chen, T.; Chen, H. Multi-level learning features for automatic classification of field crop pests. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 152, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28, Neural Information Processing Systems Conference (NIPS 2015), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016, Proceedings of the 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9905, pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.T.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. ScaledYOLOv4: Scaling cross stage partial network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13029–13038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Kharade, A.; Kesarkar, A.; Bankarmali, U. Object Detection Using YOLO. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Gao, E.; Ji, Z.; Ganchev, I. BCS_YOLO: Research on Corn Leaf Disease and Pest Detection Based on YOLOv11n. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liang, G. Overview of Research on Object Detection Based on YOLO. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Engineering, Dalian, China, 17–19 November 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, S. A comprehensive review of object detection with deep learning. Digit. Signal Process. 2023, 132, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Du, S.; Lan, X. A review of object detection based on deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 23729–23791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.T.; Wu, X. Object detection with deep learning: A review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldubaikhi, A.; Patel, S. Advancements in Small-Object Detection 2023–2025: Approaches, Datasets, Benchmarks, Applications, and Practical Guidance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Canales, A.; Gomez-Avila, J.; Hernandez-Barragan, J.; Lopez-Franco, C.; Villaseñor, C.; Arana-Daniel, N. Improving Moving Insect Detection with Difference of Features Maps in YOLO Architecture. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.Y.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ni, L.; Cai, F.; Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, N.; Tang, J.; Xue, L. Detection of agricultural pests based on YOLO. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2560, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babicki, S.; Arndt, D.; Marcu, A.; Liang, Y.; Grant, J.R.; Maciejewski, A.; Wishart, D.S. Heatmapper: Web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W147–W153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.W.; Nevard, L.M.; Clark, S.J.; Cook, S.M. Temperature-–activity relationships in Meligethes aeneus: Implications for pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seimandi-Corda, G.; Jenkins, T.; Cook, S.M. Sampling pollen beetle (Brassicogethes aeneus) pressure in oilseed rape: Which method is best? Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2785–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Malecha, Z.; Ożarowski, K.; Siemasz, R.; Chorowski, M.; Tomczuk, K.; Strochalska, B.; Wondołowska-Grabowska, A. Deep Learning for Real-Time Detection of Brassicogethes aeneus in Oilseed Rape Using the YOLOv4 Architecture. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16021075

Malecha Z, Ożarowski K, Siemasz R, Chorowski M, Tomczuk K, Strochalska B, Wondołowska-Grabowska A. Deep Learning for Real-Time Detection of Brassicogethes aeneus in Oilseed Rape Using the YOLOv4 Architecture. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16021075

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalecha, Ziemowit, Kajetan Ożarowski, Rafał Siemasz, Maciej Chorowski, Krzysztof Tomczuk, Bernadeta Strochalska, and Anna Wondołowska-Grabowska. 2026. "Deep Learning for Real-Time Detection of Brassicogethes aeneus in Oilseed Rape Using the YOLOv4 Architecture" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16021075

APA StyleMalecha, Z., Ożarowski, K., Siemasz, R., Chorowski, M., Tomczuk, K., Strochalska, B., & Wondołowska-Grabowska, A. (2026). Deep Learning for Real-Time Detection of Brassicogethes aeneus in Oilseed Rape Using the YOLOv4 Architecture. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16021075