An Autonomous UAV Power Inspection Framework with Vision-Based Waypoint Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

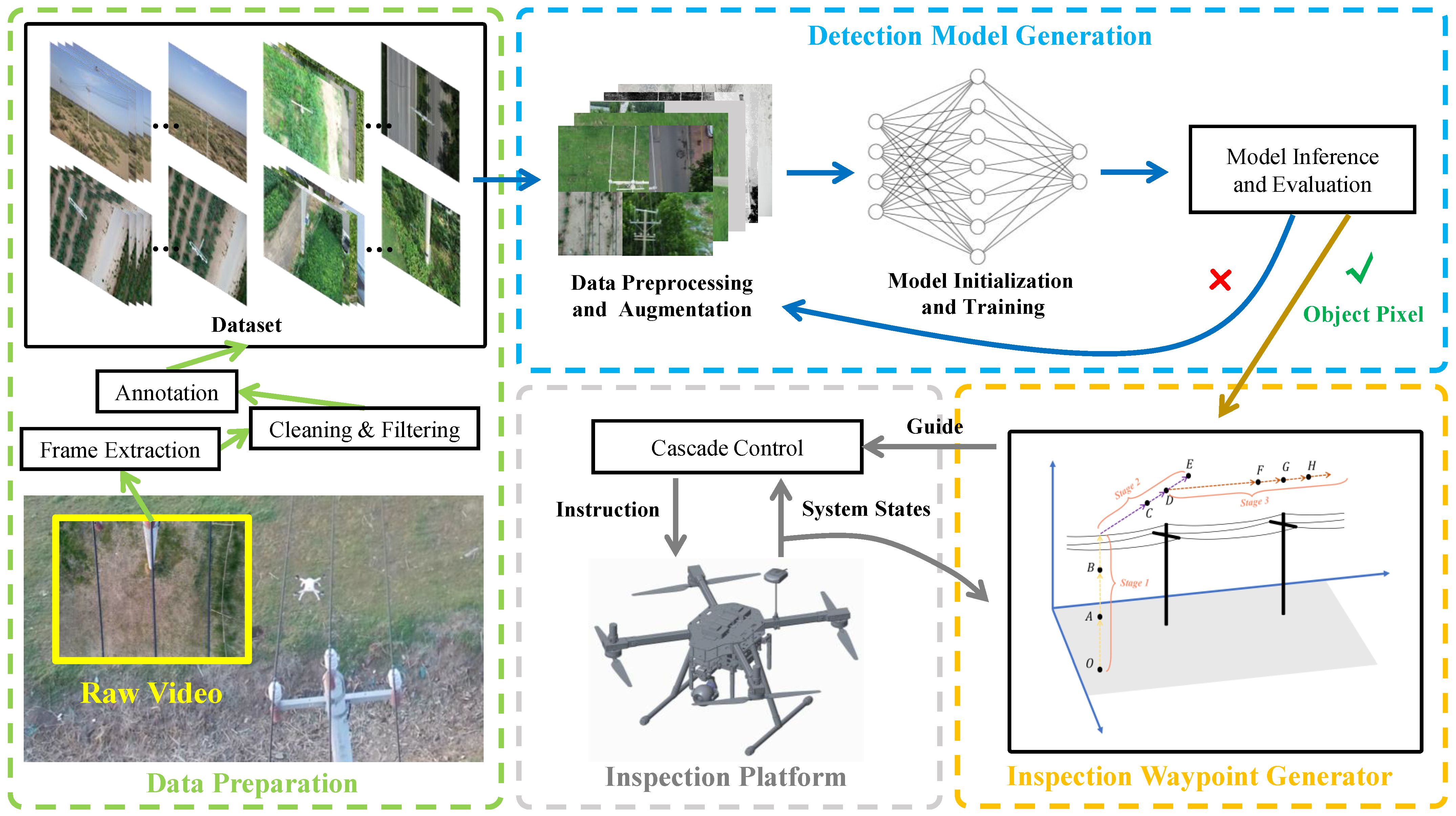

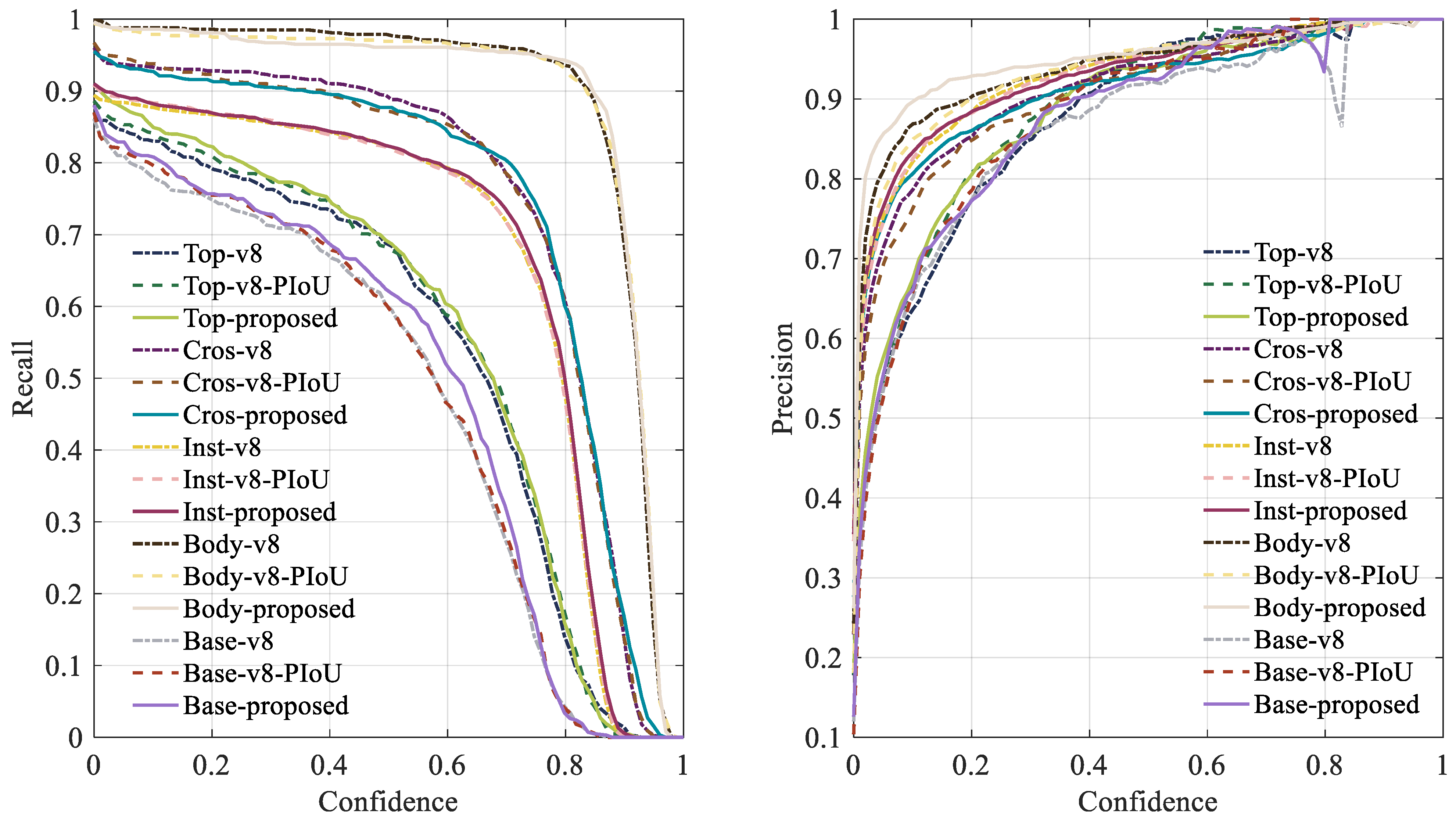

- For object detection, we established a distribution tower dataset, and then incorporated GELAN and PIoU [9] modules to enhance the YOLOv8 model by reducing model parameters and improving bounding box regression accuracy. The improved model achieves a 2.1% increase in mAP50:95 and can run at 56 FPS on an RK3588-based onboard computer.

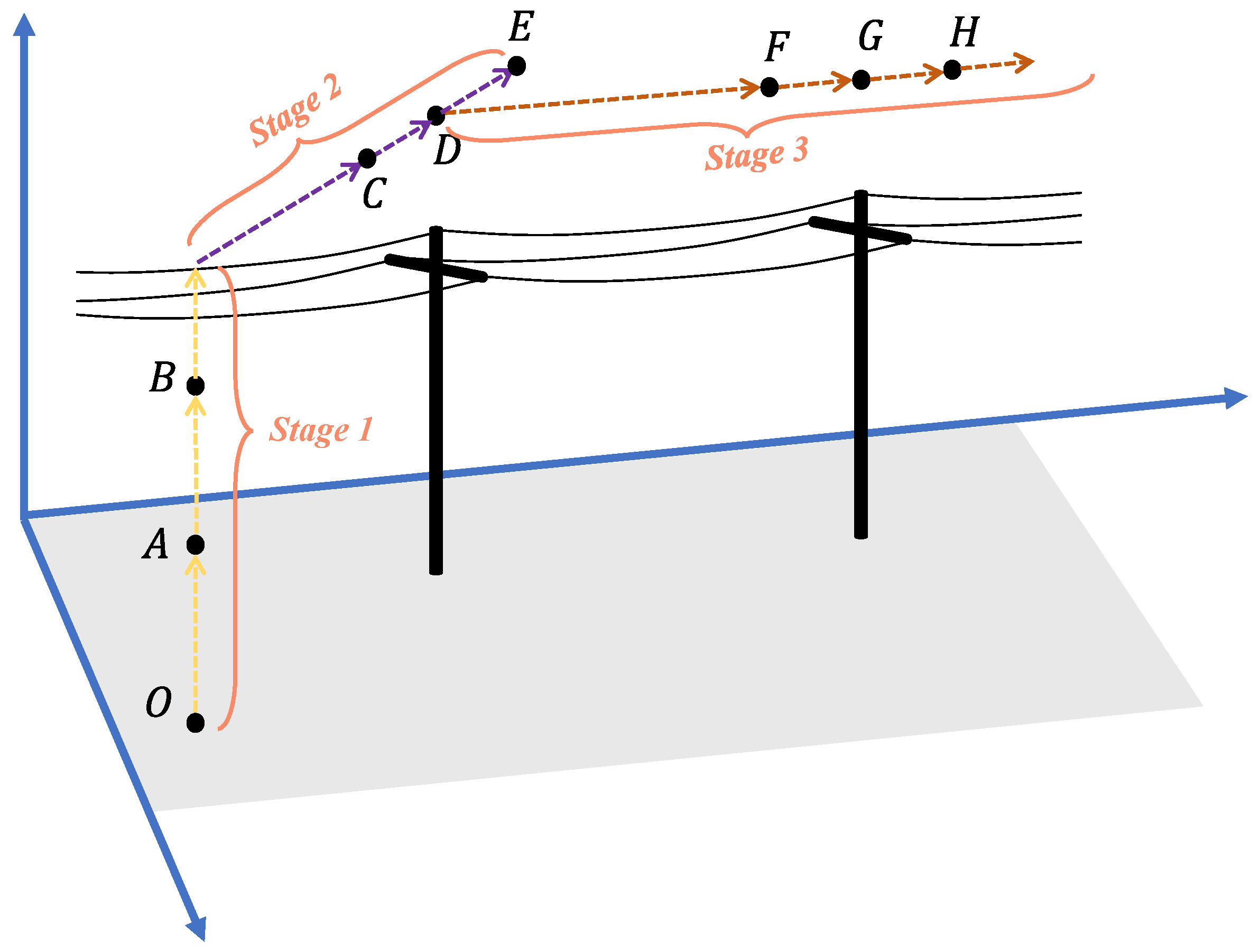

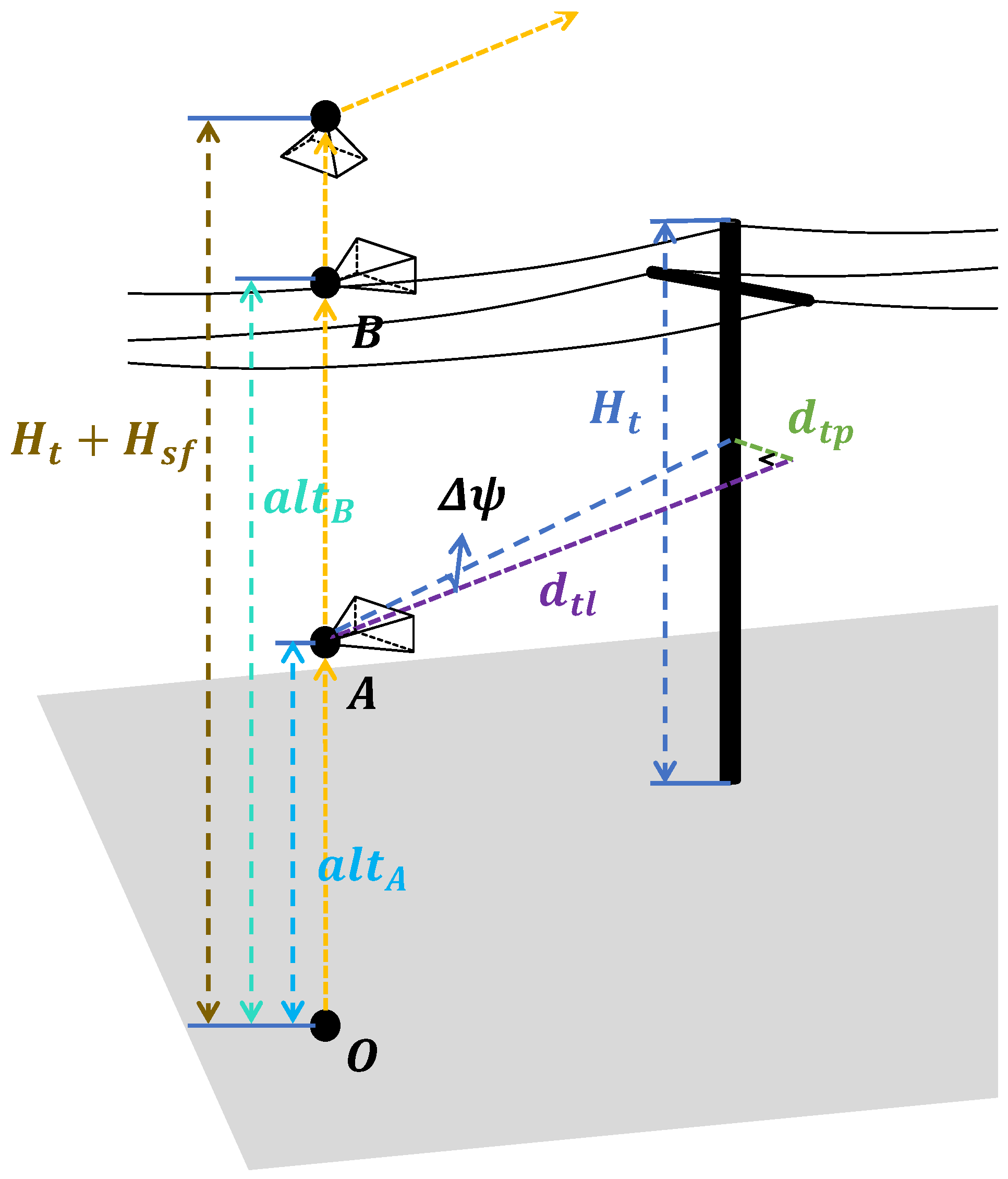

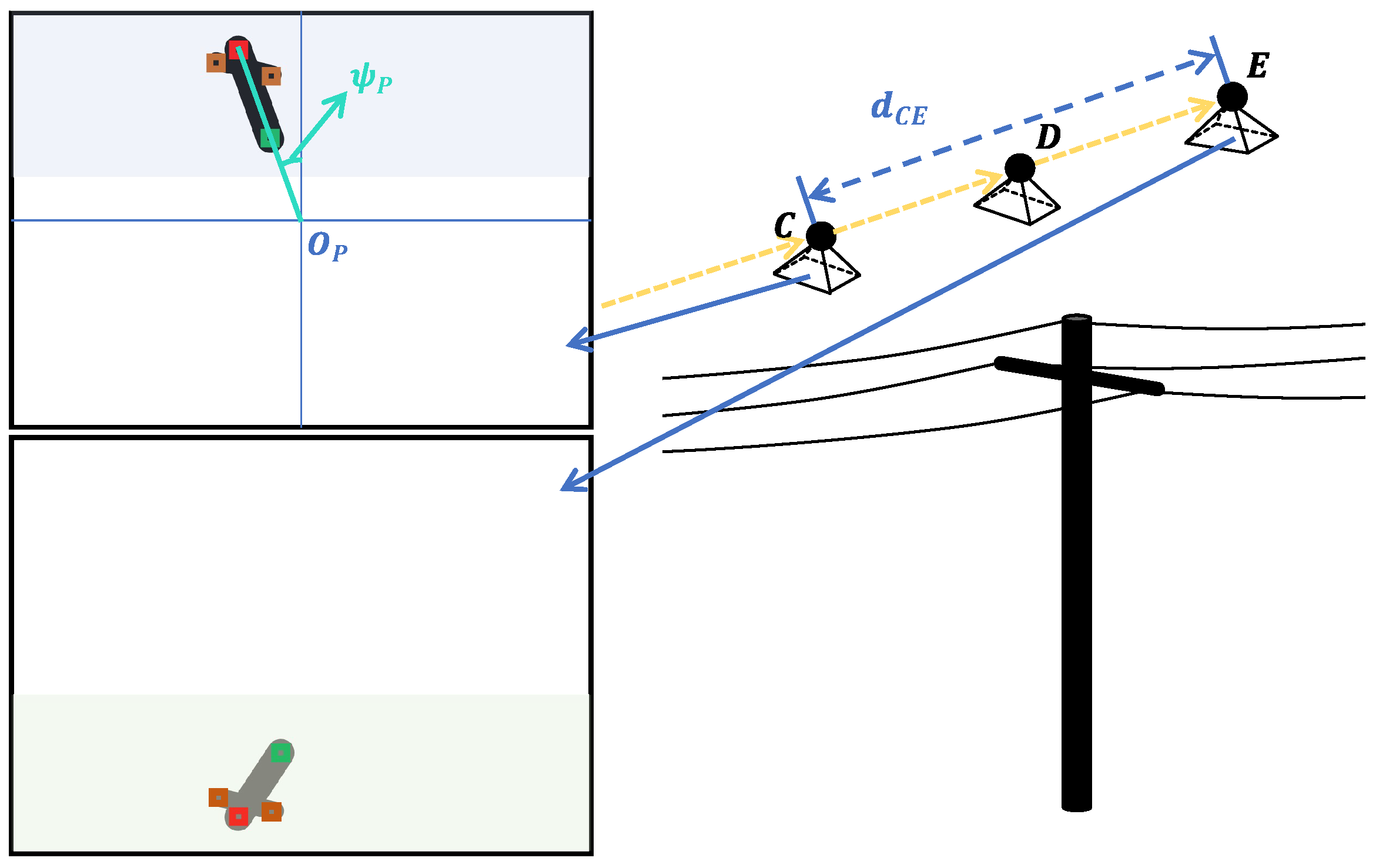

- An inspection waypoint generator is designed, which collects the UAV’s states and detection results at specific intervals, estimates the relative distance between the tower and the UAV by analyzing their relative position and pixel variations, and estimates the tower’s geographic coordinates. The generator operates in three stages: initial tower coordinate estimation, coordinate correction, and refined tower coordinate estimation.

2. Related Works

3. System Structure and Object Detection

3.1. System Structure

3.2. Tower Detection

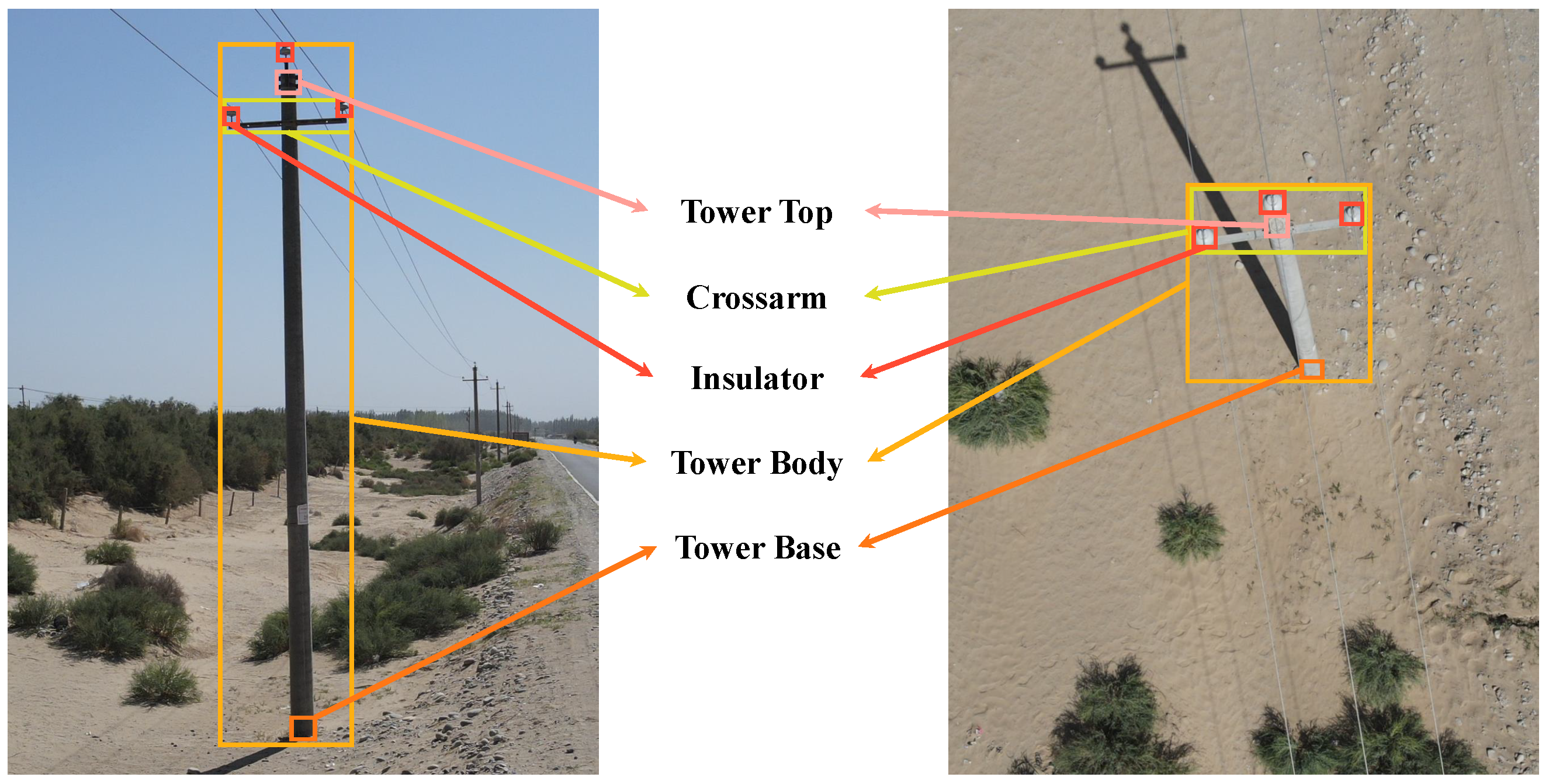

3.2.1. Dataset Description

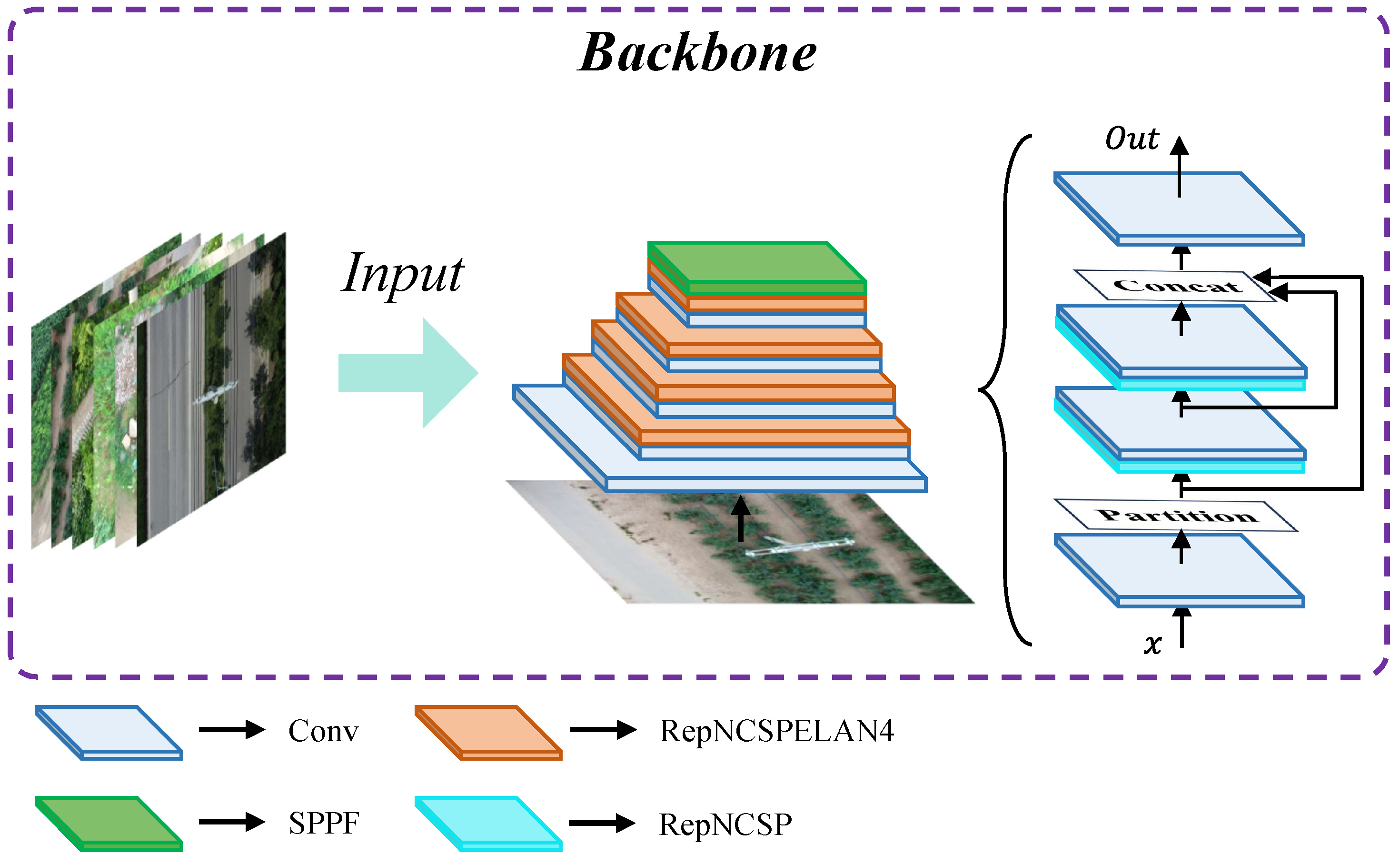

3.2.2. Improved YOLOv8

3.2.3. Lightweight Backbone

3.2.4. Bounding Box Regression

4. Inspection Waypoint Generator

4.1. Overview

4.2. Stage 1: Initial Tower Estimation

4.3. Stage 2: Initial Tower Coordinate Correction

4.4. Stage 3: Subsequent Tower Positioning

4.5. Cascade Control

5. Experiment and Verification

5.1. Model Validation

5.1.1. Model Training

5.1.2. Ablation Validation

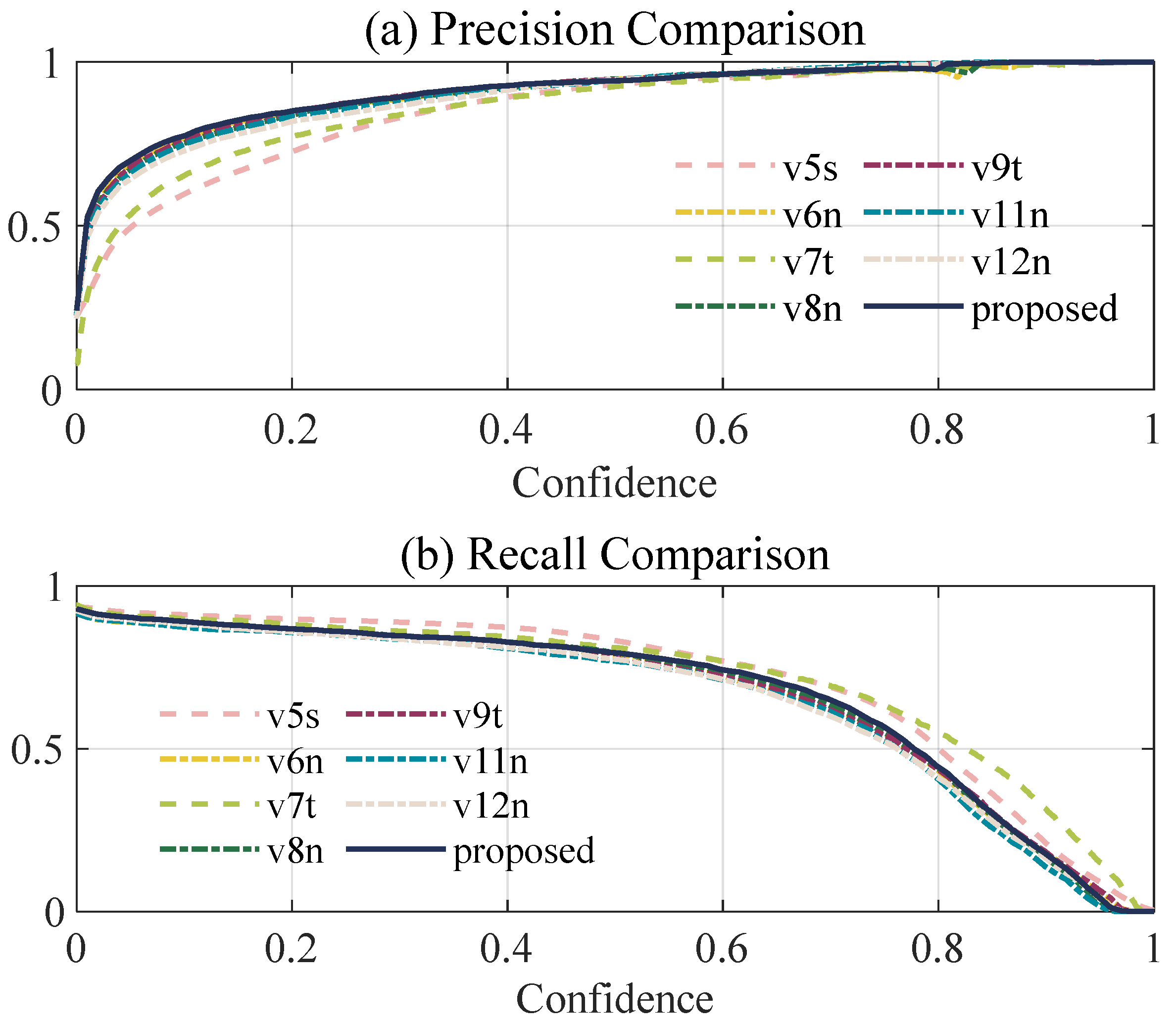

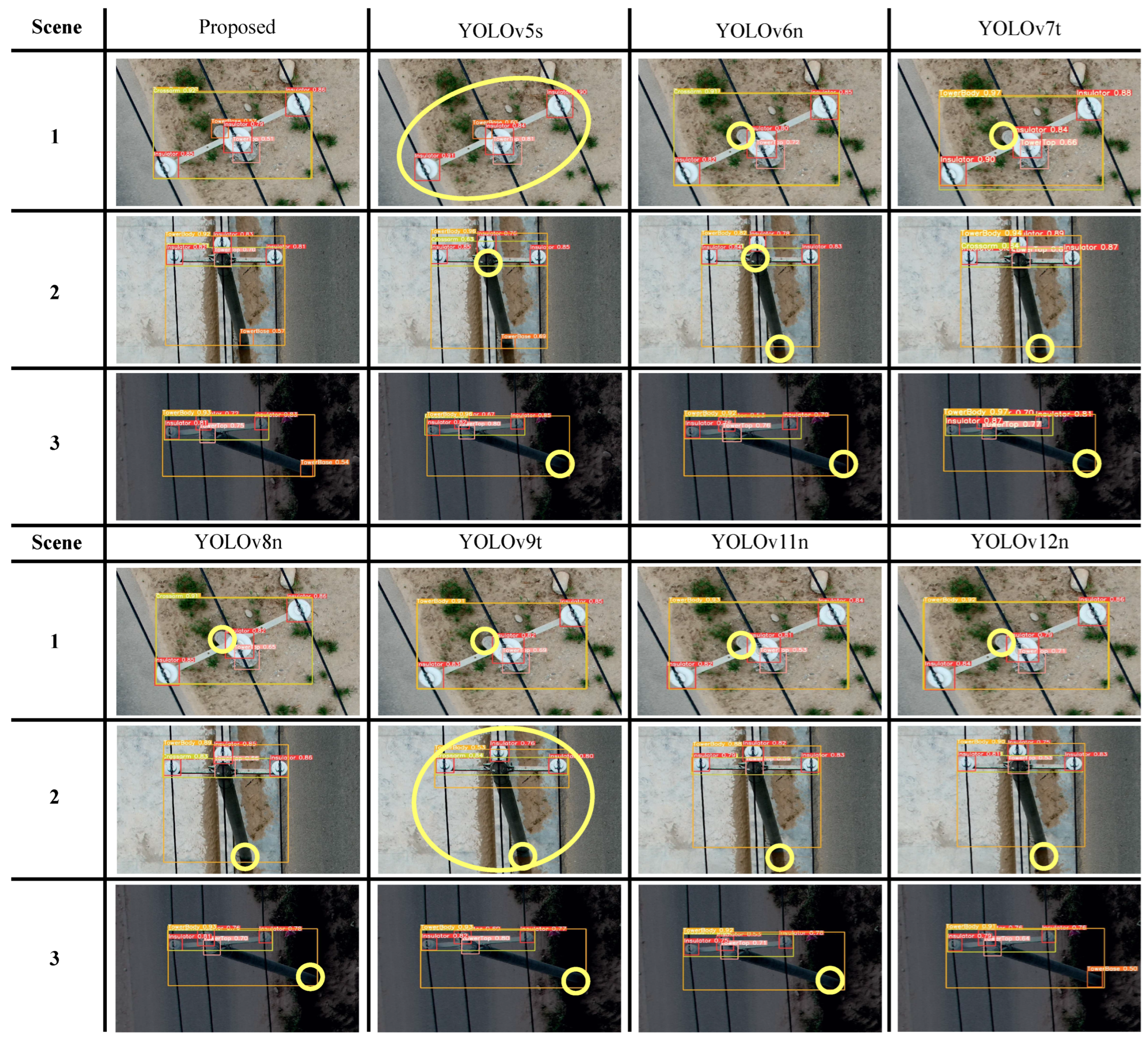

5.1.3. Model Comparisons

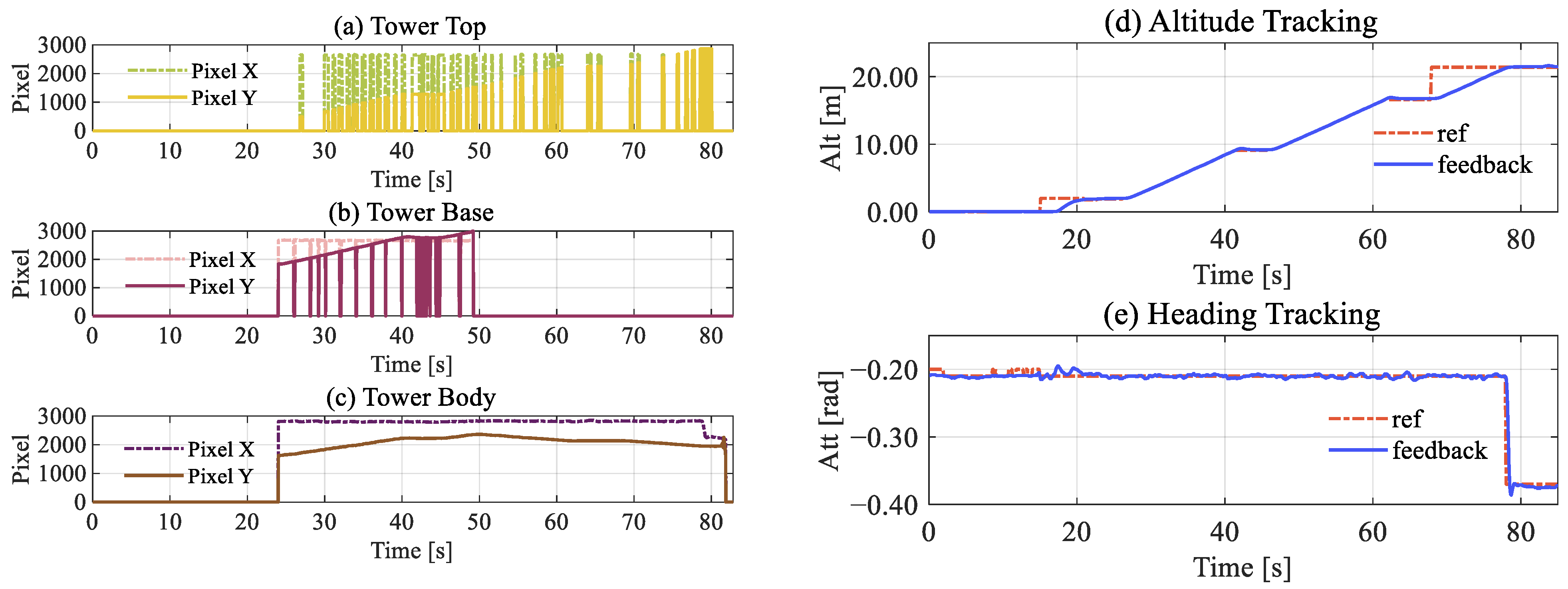

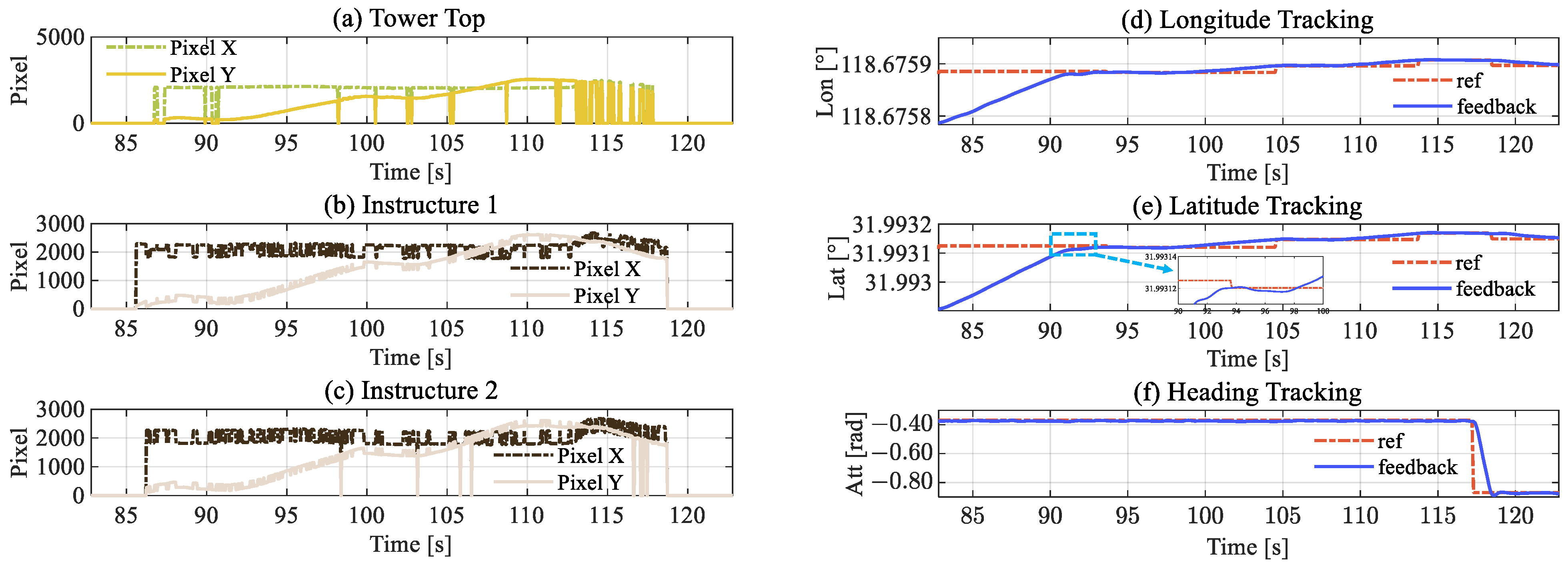

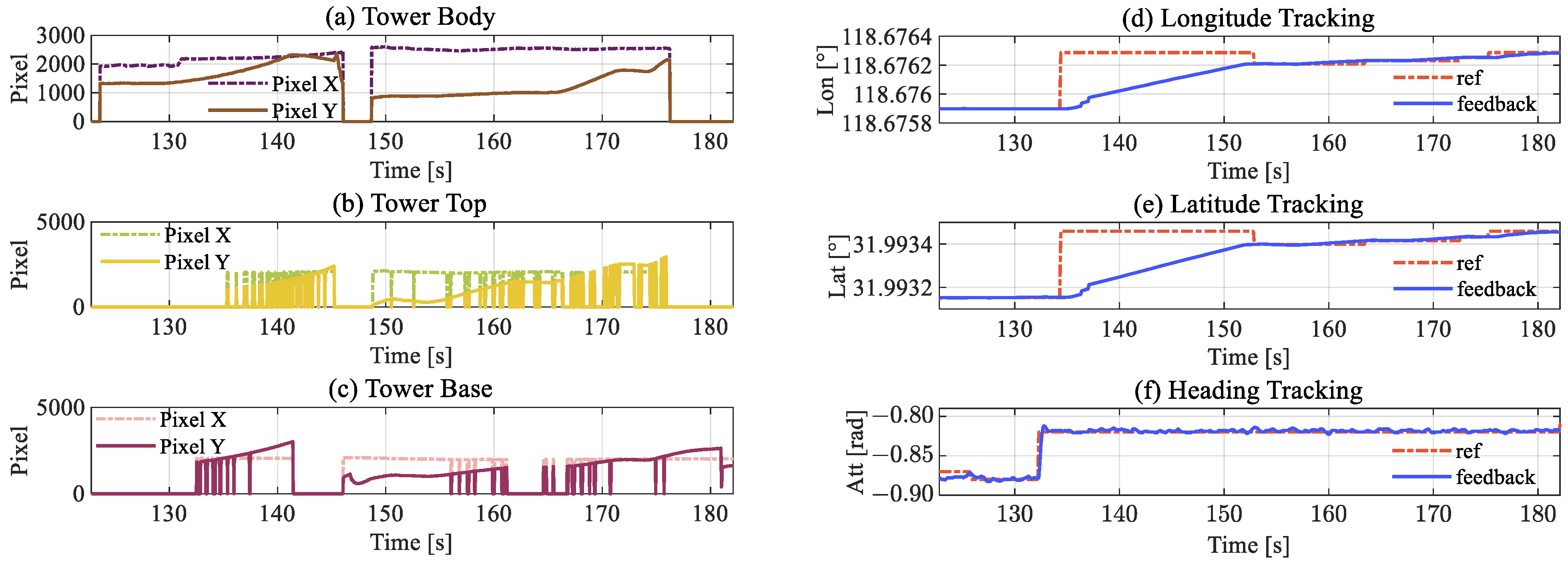

5.2. Inspection Flight Cases

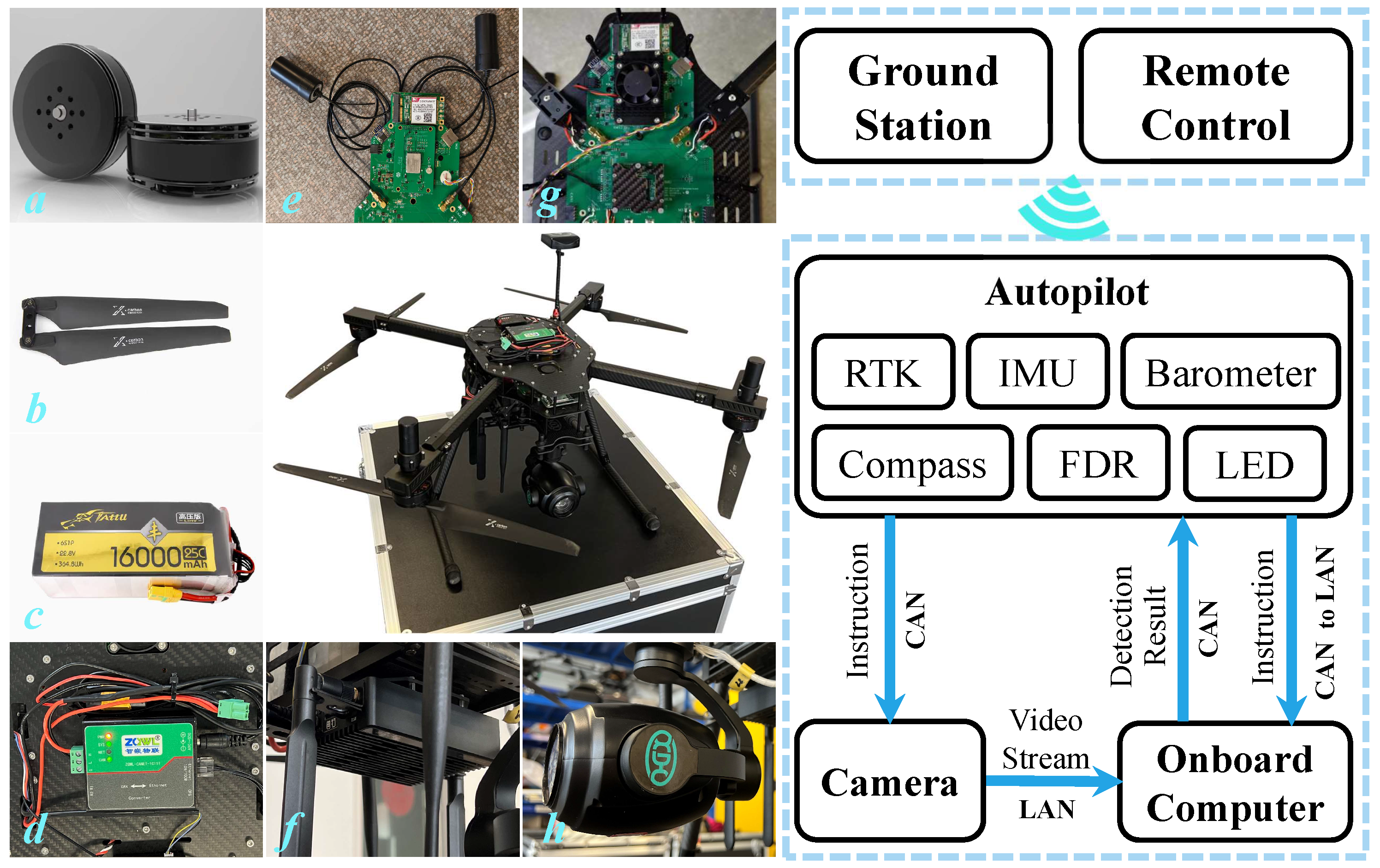

5.2.1. Inspection Platform

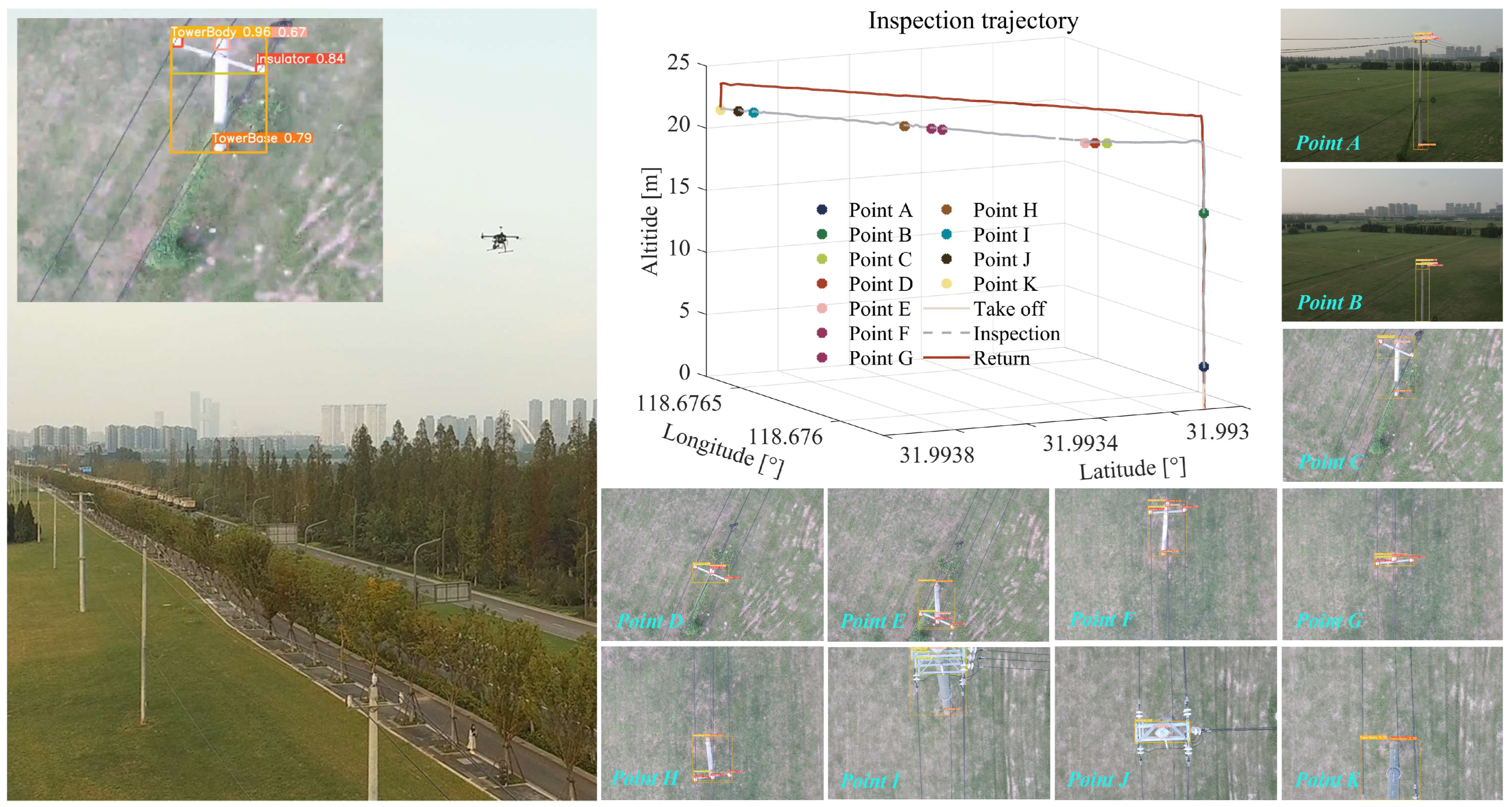

5.2.2. Inspection Implementation

6. Discussion

6.1. Inspection Performance

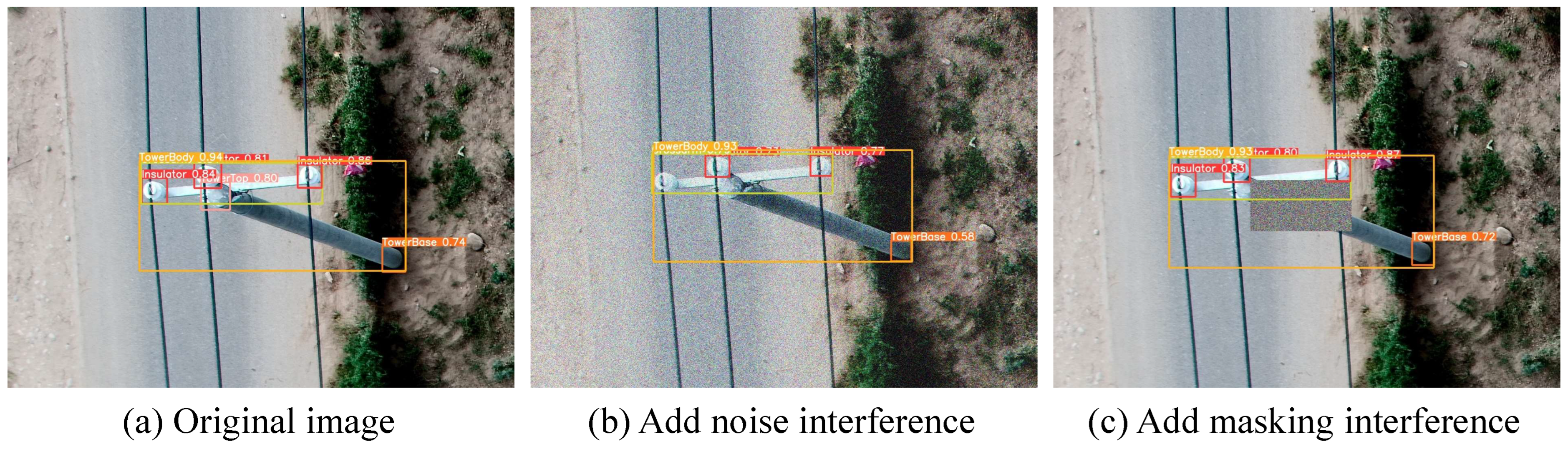

6.2. Sensitivity to Detection Noise

6.3. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, D.E.; Carreras, B.A.; Lynch, V.E.; Dobson, I. Exploring complex systems aspects of blackout risk and mitigation. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2011, 60, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A. Risk analysis and management in power outage and restoration: A literature survey. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2014, 107, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-Q.; Guo, X.-H.; Huang, P.; Li, F.-H. Safety distance analysis of 500 kv transmission line tower uav patrol inspection. IEEE Lett. Electromagn. Compat. Pract. Appl. 2020, 2, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrauri, J.I.; Sorrosal, G.; González, M. Automatic system for overhead power line inspection using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle—RELIFO project. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 28–31 May 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Song, G.; Li, S.; Zhen, F.; Chen, D.; Song, A. LineSpyX: A power line inspection robot based on digital radiography. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 4759–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, N.; Nemati, H.; Haghshenas-Jaryani, M.; Dehghan-Niri, E. An Inflatable Soft Crawling Robot with Nondestructive Testing Capability for Overhead Power Line Inspection. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA, 30 October–3 November 2022; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 86670, p. V005T07A021. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, A. A new design of a flying robot, with advanced computer vision techniques to perform self-maintenance of smart grids. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 2252–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yuan, J.; Yen, I.-L.; Bastani, F. Robust real-time UAV based power line detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 744–748. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Li, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, K.; Ma, H. Powerful-IoU: More straightforward and faster bounding box regression loss with a nonmonotonic focusing mechanism. Neural Netw. 2024, 170, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, A.; Wani, M.A. You only look once-object detection models: A review. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 15–17 March 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1088–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qi, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, W. Detection method based on automatic visual shape clustering for pin-missing defect in transmission lines. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 6080–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Q.; Jin, S.; Chen, C.; Feng, S. Research on detection method of transmission line strand breakage based on improved YOLOv8 network model. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 168197–168212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Fang, X.; Miao, Q. Transmission tower and Power line detection based on improved Solov2. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5015711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, P.; Kong, Q.; Han, Z. Gdipayolo: A fault detection algorithm for uav power inspection scenarios. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qu, C.; Ru, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Multi-objects recognition and self-explosion defect detection method for insulators based on lightweight GhostNet-YOLOV4 model deployed onboard UAV. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 39713–39725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, F.; Wei, S.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Lu, Z. Detail R-CNN: Insulator detection based on detail feature enhancement and metric learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 2524414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Shang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhai, P.; Geng, C. DSA-Net: An Attention-Guided Network for Real-Time Defect Detection of Transmission Line Dampers Applied to UAV Inspections. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 73, 3501022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X. Foreign objects identification of transmission line based on improved YOLOv7. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51997–52008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Guo, L.; Chen, R.; Du, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Kong, X.; Tang, J. Improved YOLOX foreign object detection algorithm for transmission lines. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 5835693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Liao, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Z. A method based on multi-network feature fusion and random forest for foreign objects detection on transmission lines. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yu, D.; Ma, Y. Power line-guided automatic electric transmission line inspection system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3512118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Qin, L.; Deng, X.; Liu, K. MFI-YOLO: Multi-fault insulator detection based on an improved YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 39, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z. Improved YOLOv3 network for insulator detection in aerial images with diverse background interference. Electronics 2021, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Sun, X.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, C.; Guo, Q. UAV-lidar aids automatic intelligent powerline inspection. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 130, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Cioffi, G.; Hidalgo-Carrió, J.; Scaramuzza, D. Autonomous power line inspection with drones via perception-aware MPC. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1086–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, A.; Silano, G.; Capitán, J. Mission planning and execution in heterogeneous teams of aerial robots supporting power line inspection operations. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1644–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Ju, C.; Suzuki, S.; Namiki, A. UAV high-voltage power transmission line autonomous correction inspection system based on object detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 10215–10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Namiki, A.; Suzuki, S. Close-Range Transmission Line Inspection Method for Low-Cost UAV: Design and Implementation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, O.B.; Iversen, N.; Ebeid, E. Autonomous power line detection and tracking system using UAVs. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 94, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, R.; Roverso, D. Automatic autonomous vision-based power line inspection: A review of current status and the potential role of deep learning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 99, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.; Tardos, J.D. Orb-slam3: An accurate open-source library for visual, visual–inertial, and multimap slam. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, J.; Carlone, L. Teaser: Fast and certifiable point cloud registration. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 37, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Vision-based navigation techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: Review and challenges. Drones 2023, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.; Khan, M.A.; Fahim, H.; He, B.; Saeed, N. Explainable AI and monocular vision for enhanced UAV navigation in smart cities: Prospects and challenges. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1561404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Kooistra, L.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Valente, J. Real-time object detection based on uav remote sensing A systematic literature review. Drones 2023, 7, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.; Honegger, D.; Pollefeys, M. PX4: A node-based multithreaded open source robotics framework for deeply embedded platforms. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 6235–6240. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira e Silva, A.L.B.; de Castro Felix, H.; Simoes, F.P.M.; Teichrieb, V.; dos Santos, M.; Santiago, H.; Sgottib, V.; Lott Neto, H. A dataset and benchmark for power line asset inspection in uav images. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2023, 44, 7294–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D. Detection of power line insulator defects using aerial images analyzed with convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 1486–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, R.; Maturana, D.; Scherer, S. Wire detection using synthetic data and dilated convolutional networks for unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3487–3494. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision, Proceedings of the ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part V 13; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.B.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Hasan-Zia, M.; Kashem, S.B.A.; Majid, M.E.; Ansaruddin Kunju, A.K.; Khandakar, A.; Ashraf, A.; Nashbat, M. VisioDECT: A novel approach to drone detection using CBAM-integrated YOLO and GELAN-E models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 20181–20204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Letchmunan, S.; Xiao, R. Gelan-SE: Squeeze and stimulus attention based target detection network for gelan architecture. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 182259–182273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Du, G.-X.; Cai, K.-Y. Proportional-integral stabilizing control of a class of MIMO systems subject to nonparametric uncertainties by additive-state-decomposition dynamic inversion design. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 21, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Agrawal, R. A Comprehensive Review of YOLOv5: Advances in Real-Time Object Detection. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Reddy, R.; Venkata, C. A review on yolov8 and its advancements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics, Tirunelveli, India, 18–20 November 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y.M. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Sensor Cost | Map Dependency | Manual Intervention | Operational Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | Medium | Low | Low | Based on a camera sensor; requires manual guidance to inspection target. |

| [27] | Medium | High | None | Based on a camera sensor; requires a map of tower locations. |

| [28] | Highly | High | None | Based on high-precision positioning devices and predefined waypoints. |

| [29] | Medium | High | High | Based on preset waypoints, radar, and camera sensors. |

| [30] | Medium | Medium | Medium | Based on solid-state LiDAR and cameras; requires manual guidance for UAVs to patrol targets. |

| [32] | Medium | Low | None | Relies on feature points; prone to tracking failure in texture-less backgrounds. |

| [33] | High | High | None | Relies on geometric registration; constrained by high payload weight and power consumption. |

| Proposed | Low | None | None | Based on a camera; |

| Object Class | Training Instances | Validation Instances | Total Instances |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tower Top | 6400 | 1550 | 7950 |

| Tower Body | 6500 | 1570 | 8070 |

| Tower Base | 5200 | 1260 | 6460 |

| Crossarm | 9100 | 2200 | 11,300 |

| Insulator | 26,500 | 6450 | 32,950 |

| Total Images | 7000 | 1700 | 8700 |

| YOLO | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| v8n | 0.8845 | 0.6025 | 0.9133 | 0.8358 |

| v8n-GELAN | 0.8836 | 0.6028 | 0.9110 | 0.8299 |

| v8n-PIoU | 0.8972 | 0.6132 | 0.9128 | 0.8414 |

| Proposed | 0.8971 | 0.6144 | 0.9189 | 0.8368 |

| YOLO | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Precision | Recall | Parameters | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v5s | 0.8897 | 0.5836 | 0.9099 | 0.8653 | 7.03 M | 36 |

| v6n | 0.8842 | 0.5983 | 0.9160 | 0.8290 | 4.24 M | 50 |

| v7t | 0.8864 | 0.5672 | 0.9030 | 0.8417 | 6.03 M | 54 |

| v8n | 0.8845 | 0.6025 | 0.9133 | 0.8358 | 3.01 M | 52 |

| v9t | 0.8853 | 0.6083 | 0.9112 | 0.8303 | 2.01 M | 39 |

| v11n | 0.8792 | 0.5992 | 0.8994 | 0.8373 | 2.59 M | 50 |

| v12n | 0.8834 | 0.5983 | 0.9162 | 0.8096 | 2.57 M | 44 |

| Proposed | 0.8971 | 0.6144 | 0.9189 | 0.8368 | 2.01 M | 56 |

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3-1 | Stage 3-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Coordinate | (118.67588544, 31.99312495) | (118.67589890, 31.99315348) | (118.67628796, 31.99345934) | (118.67665632, 31.99375512) |

| Actual Coordinate | (118.67589719, 31.99314869) | (118.67589719, 31.99314869) | (118.67628744, 31.99345916) | (118.67666469, 31.99376036) |

| N Distance error [m] | 2.641 | −0.533 | 0.02 | −0.583 |

| E Distance error [m] | 1.111 | −0.161 | 0.05 | −0.790 |

| Azimuth error [rad] | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W. An Autonomous UAV Power Inspection Framework with Vision-Based Waypoint Generation. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010076

Wang Q, Zhang Z, Wang W. An Autonomous UAV Power Inspection Framework with Vision-Based Waypoint Generation. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qi, Zixuan Zhang, and Wei Wang. 2026. "An Autonomous UAV Power Inspection Framework with Vision-Based Waypoint Generation" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010076

APA StyleWang, Q., Zhang, Z., & Wang, W. (2026). An Autonomous UAV Power Inspection Framework with Vision-Based Waypoint Generation. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010076