High-Speed Electric Motors for Fuel Cell Compressor System Used for EV Application—Review and Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Database Selection: The literature search was conducted using MDPI, Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect, which collectively cover the majority of peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings in the field of electric machines, compressors, and fuel cell technologies.

- -

- Search Strategy: Keyword combinations such as “fuel cell air compressor”, “high-speed electric motor”, “materials”, “mechanical challenges and constraints”, “thermal problems”, “efficiency parameters”, “optimization”, and “durability” were applied using Boolean operators (“and”, “or”).

- -

- Time Span and Language: Publications between 2005 and 2025, written in English, were included to capture recent technological and scientific advances.

- -

- Inclusion Criteria: Studies were included if they addressed: the electric motor topology and operation within FC systems, if it would consider the analysis of compressor technologies for fuel cells or if they examined efficiency and durability topics.

- -

- Exclusion Criteria: Publications unrelated to FC applications (e.g., general industrial compressors or non-hydrogen systems) were excluded.

- -

- Screening and Classification: After initial retrieval, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. The remaining studies were classified into categories such as FC compressor topologies, motor variants, materials and durability, and system integration.

- -

- Analysis and Synthesis: Quantitative bibliometric indicators (e.g., publication trends, keyword frequency) and qualitative assessments were combined to identify technological gaps and future research needs.

- -

- Among broader “fuel cell system” reviews, the fraction that dive into compressor/air-supply subsystem is very small.

- -

- The number of dedicated reviews on compressors for fuel-cell systems is extremely limited, since over the past 5 years only one review (from 2025) appears to focus on compressor/air-supply in FC systems, but it concerns mechanical hydraulic topologies.

- -

- The proportion of reviews in the past 5 years that address FC-compressors (or air/oxygen supply systems) is likely < 10% of total “FC system review” articles.

- -

- A comprehensive review dedicated to HSEM has not yet been conducted.

2. HSEM for FC System

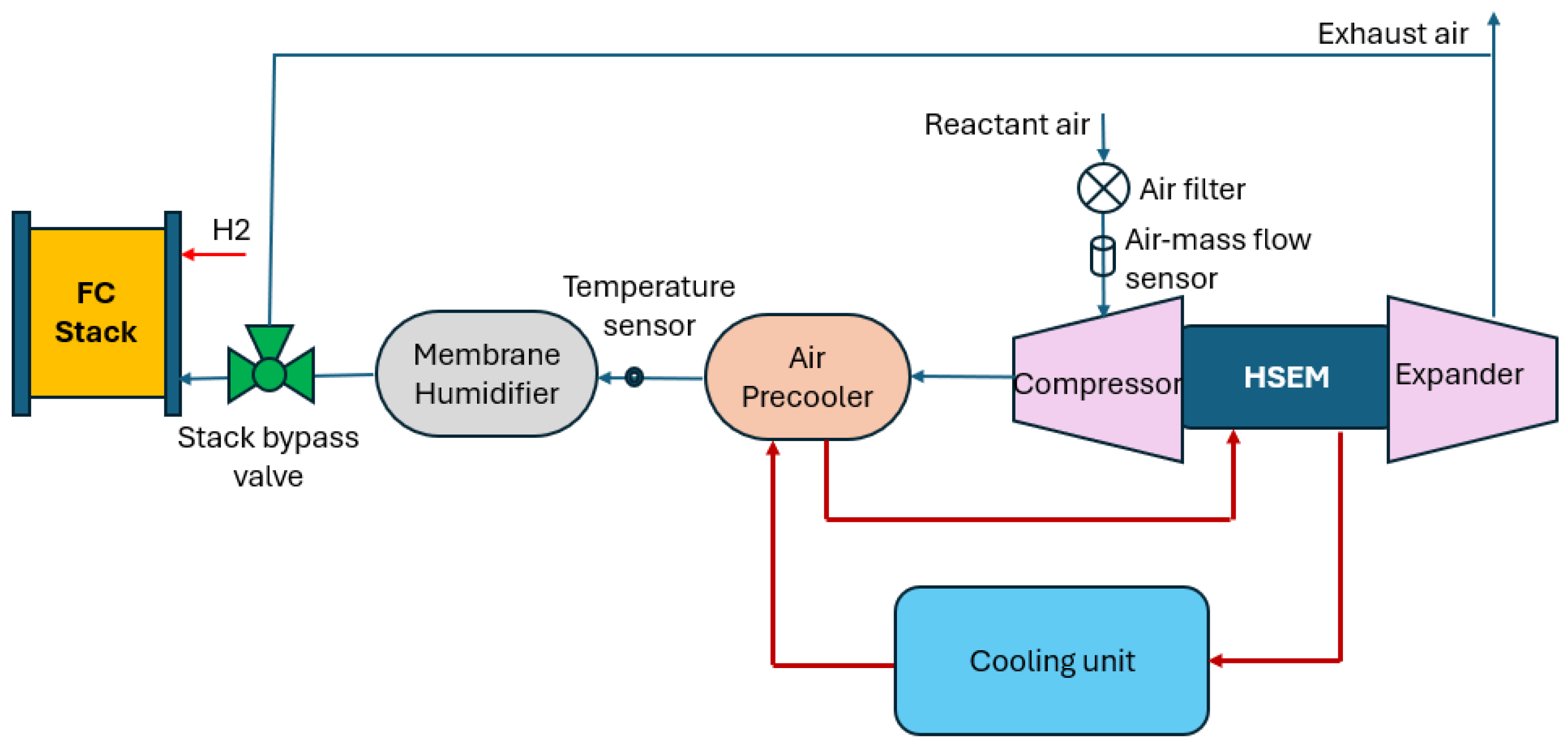

2.1. The FC System Application

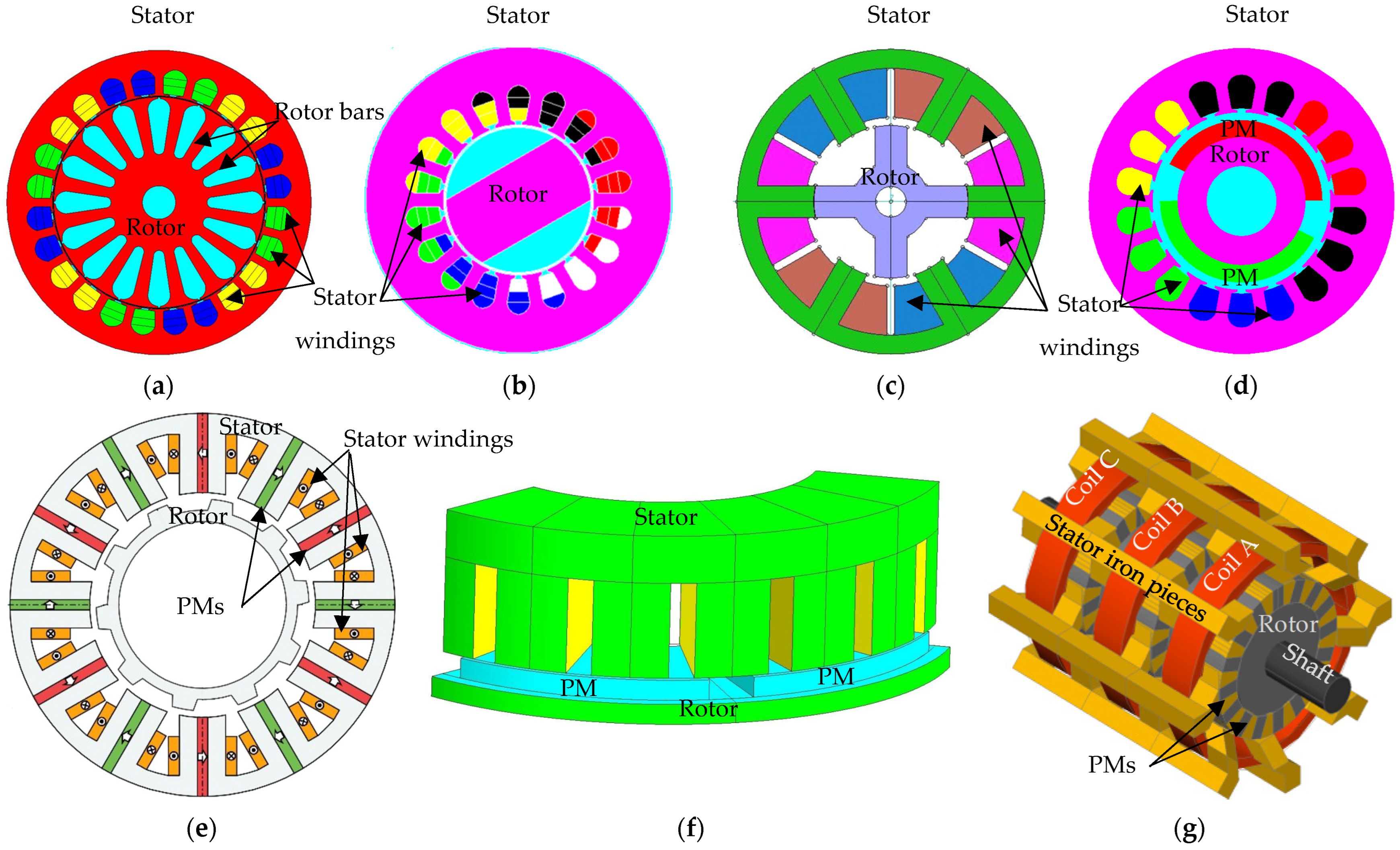

2.2. HSEM Topologies—Current Trends

2.3. Study Cases—HSEM for FC Compressor Application

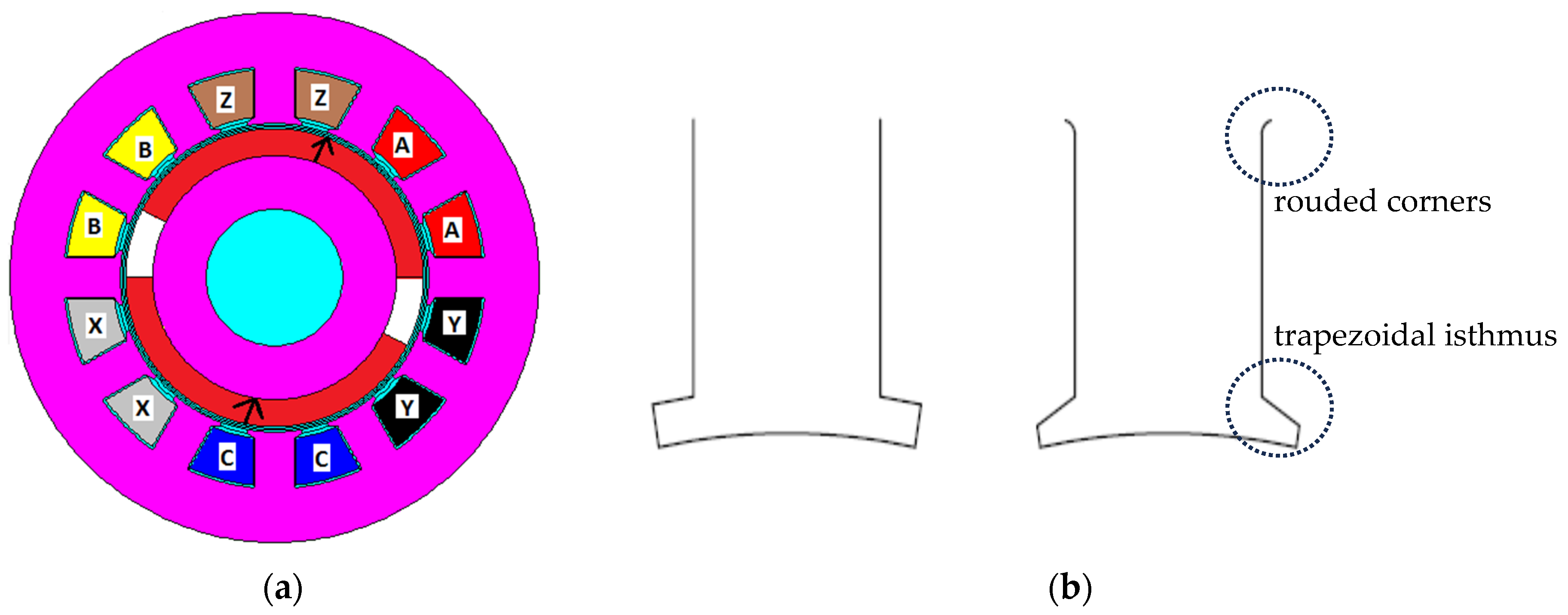

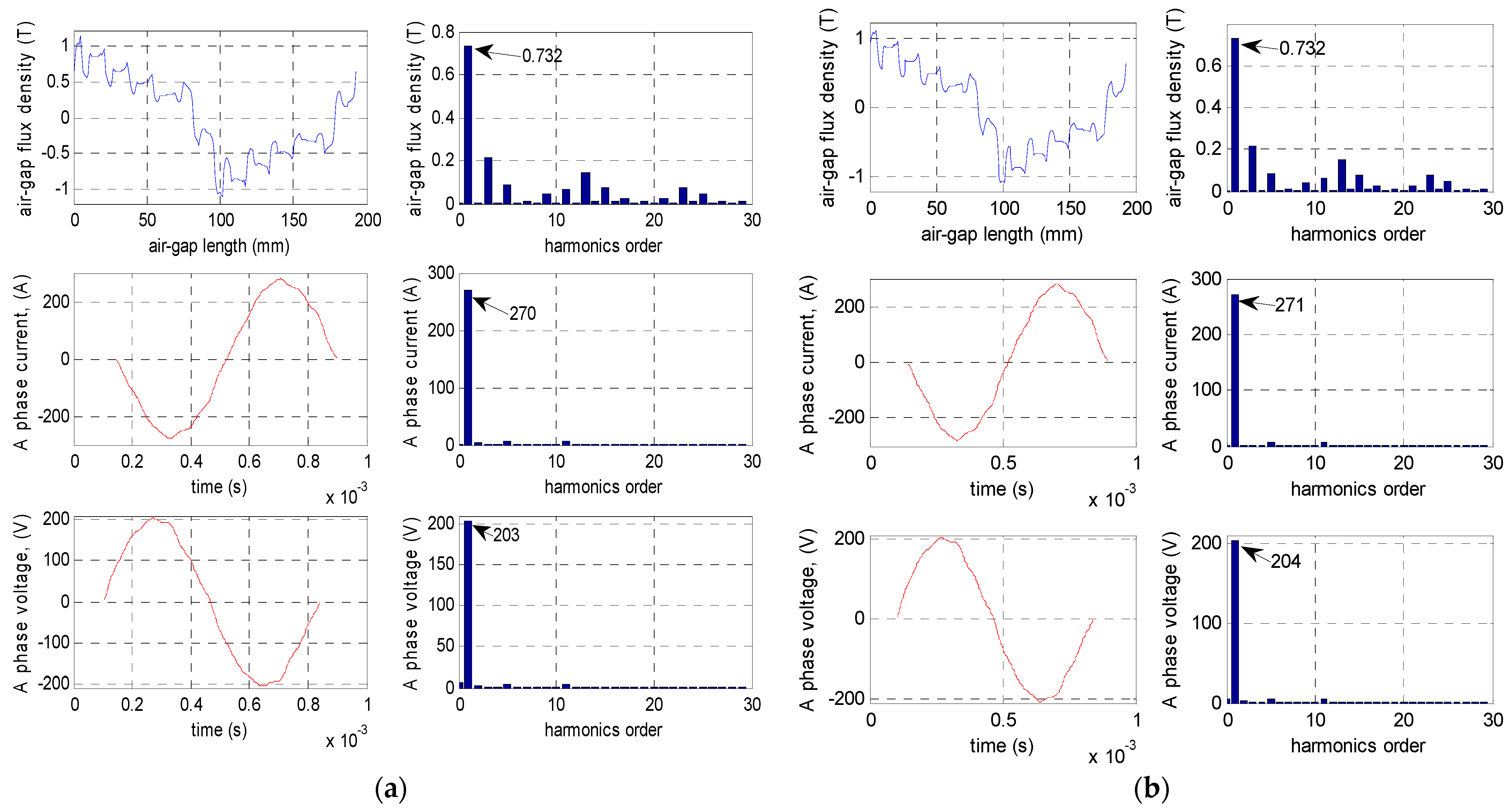

2.3.1. Study Case 1—High Speed Synchronous Reluctance Motor (HS-SynRM)

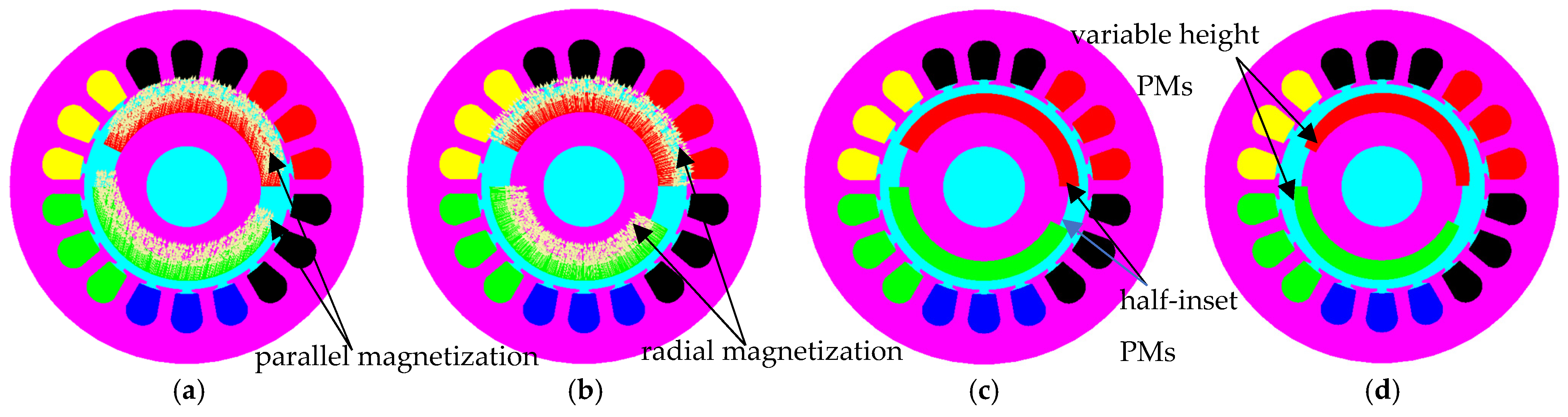

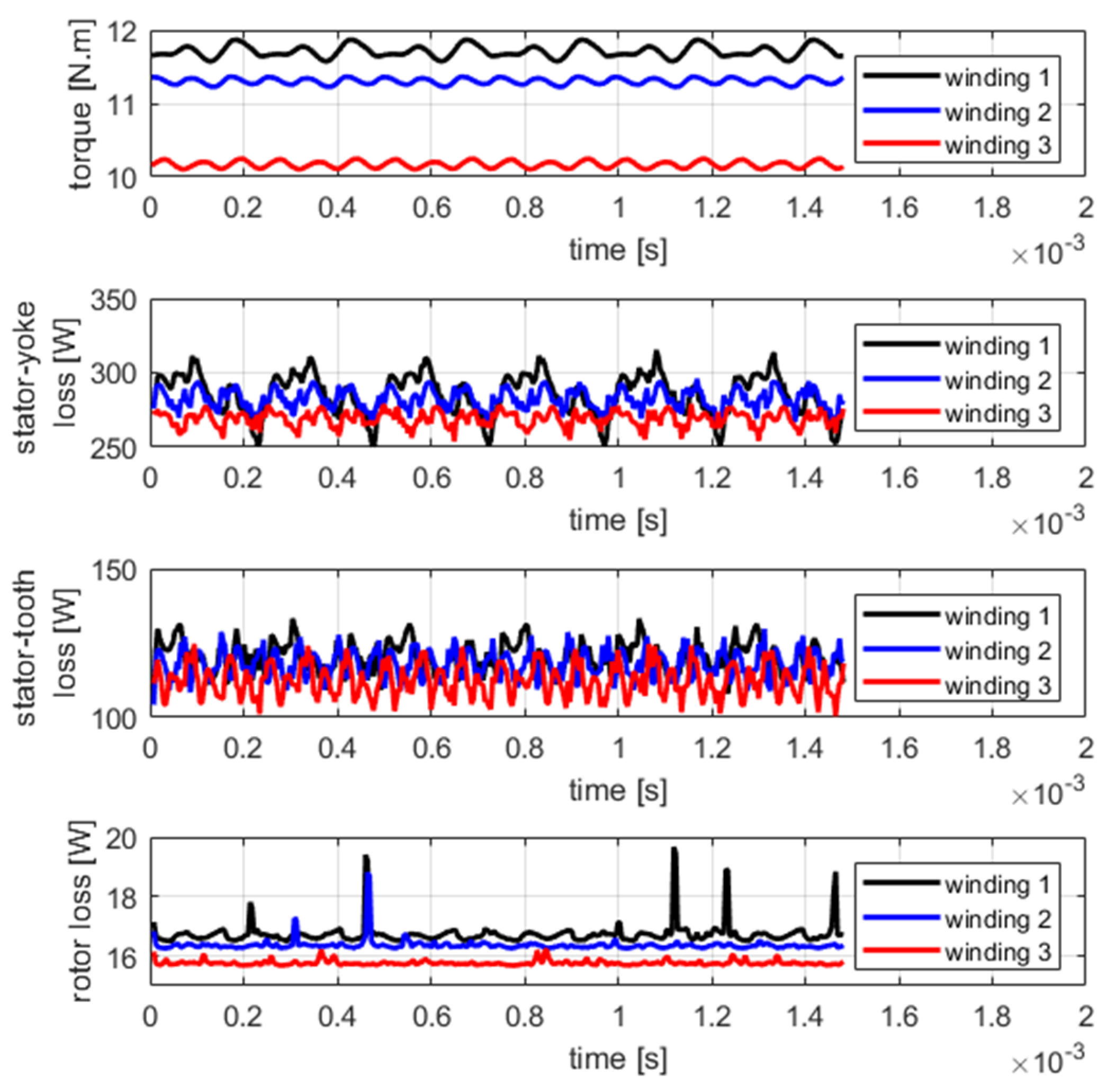

2.3.2. Study Case 2—High Speed Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (HS-PMSM)

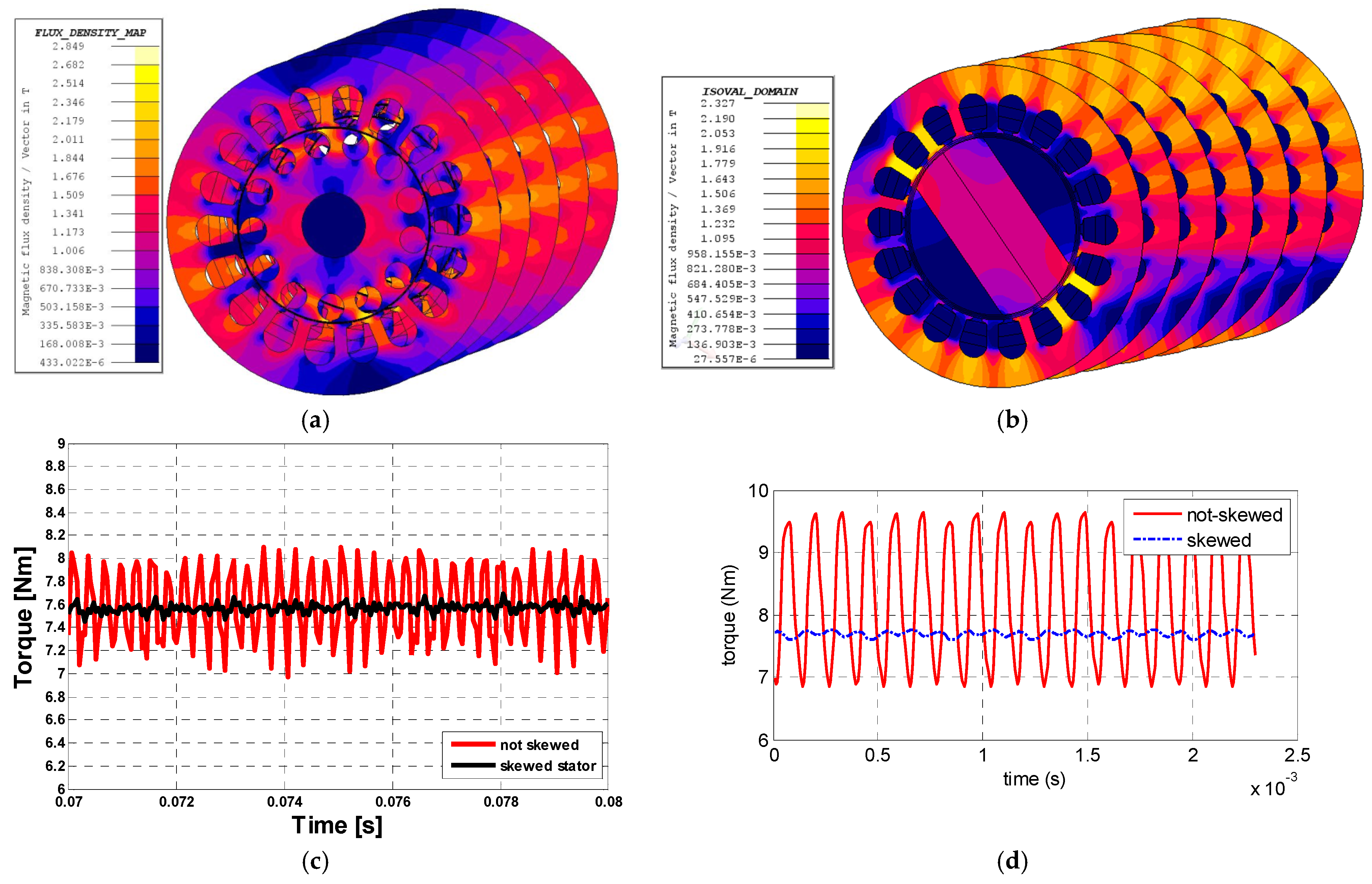

2.3.3. Study Case—High Speed Induction Motor (HS-IM)

3. Technological Trends for Efficiency Improvement for HSEM

3.1. Materials Used in the Construction of HESM

3.2. Technology Improvement for HSEM

3.2.1. Winding Configurations

3.2.2. Insulation

3.2.3. Geometry Configurations

3.2.4. Mechanical Consolidation

3.2.5. Cooling for HSEM

3.2.6. Optimization of HSEM

- Choosing the optimization variables (starting value and boundaries);

- Imposing special limitations on other variables;

- Defining the objective function;

- Setting the initial and final values of global increment (initially, with a larger increment, which will be further decreased to refine the search space);

- Computing the geometrical and electromagnetic parameters, and the objective function;

- Making a movement in the solution space and recomputing the objective function and its gradient;

- Moving to the better solution, while the objective function decreases;

- h.

- Reducing the variation step and repeating the previous steps (the algorithm stops when the research movement cannot find a better solution, even with the smallest variation step).

3.2.7. The Durability of HSEM Within the FC System Application

3.2.8. Comparison of the Studied HS-EM Topologies for a Given Operating Point

3.3. Extras

3.3.1. Discussions on the Impeller of the Compressor Subsystem

- -

- The Centrifugal Compressor is a dynamic compressor that utilizes the centrifugal force generated by a rotating impeller to accelerate and compress the working fluid. It exhibits high efficiency at elevated flow rates; however, its performance decreases at higher pressure ratios.

- -

- The Claw Compressor operates with two non-contact, counter-rotating claw-shaped rotors. This design enables oil-free (dry) compression, ensuring clean gas delivery and high operational reliability, particularly in industrial applications.

- -

- The Lobe Compressor comprises two or more rotating lobes that displace air through the compression chamber. Although it features a simple mechanical design and robust operation, its overall efficiency is generally lower compared to other positive displacement compressors.

- -

- The Membrane Compressor employs a flexible diaphragm that oscillates or pulsates to compress air. It is particularly suited for applications requiring high gas purity, as it eliminates oil contamination and prevents direct contact between moving mechanical parts and the airflow.

- -

- The Piston Compressor utilizes a reciprocating piston within a cylinder to achieve compression. This conventional positive displacement design can attain high pressures, but it is typically characterized by significant weight, noise, and vibration.

- -

- The Rotary Vane Compressor incorporates an eccentric rotor equipped with sliding vanes that divide the compression chamber into variable volumes. It offers compactness, mechanical reliability, and relatively low noise levels, making it a versatile choice for medium-pressure applications.

- -

- The Screw Compressor employs two intermeshing helical rotors to progressively compress air as it is conveyed along the rotor axes. This configuration provides high efficiency, low noise, and long service life, making it well-suited for continuous-duty operation.

- -

- The Scroll Compressor consists of two spiral elements: one stationary and one orbiting, that compress air through a series of increasingly confined pockets. It operates with minimal noise and vibration, does not require lubrication.

- -

- The Side-Channel Compressor, utilizes an impeller with blades rotating within a housing that incorporates side channels to impart both radial and axial velocity components to the air. It enables gentle, oil-free compression at high volumetric flow rates and low pressures; it is commonly employed in blower-type applications.

3.3.2. Compressor’s Duty Cycle and Transient Requirements

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerada, D.; Mebarki, A.; Brown, N.L.; Gerada, C.; Cavagnino, A.; Boglietti, A. High-Speed Electrical Machines: Technologies, Trends, and Developments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 2946–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Le, Y. Rotor dynamics modelling and analysis of high-speed permanent magnet electrical machine rotors. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wu, L.; Zheng, Y. Multi-Objective Optimal Design of High-Speed Surface-Mounted Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for Magnetically Levitated Flywheel Energy Storage System. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8202708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Wang, K.; Han, B.; Zheng, S. Thermal Analysis and Experimental Validation of a 30 kW 60,000 r/min High-Speed Permanent Magnet Motor with Magnetic Bearings. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 92184–92192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lin, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D. Electromagnetic performance analysis of a new high-speed hybrid excitation synchronous machine. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2024, 18, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tameemi, A.; Degano, M.; Murataliyev, M.; Di Nardo, M.; Valente, G.; Gerada, D.; Xu, Z.; Gerada, C. Design procedure and optimisation methodology of permanent magnet synchronous machines with direct slot cooling for aviation electrification. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2023, 17, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.J.; Jordan, S. Comparison of Two Transverse Flux Machines for an Aerospace Application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 5783–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerada, D.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Gerada, C. Fully-integrated high-speed IM for improving high-power marine engines. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2019, 13, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhu, J.; Chen, C. A Novel Detection Scheme for Motor Bearing Structure Defects in a High-Speed Train Using Stator Current. Sensors 2024, 24, 7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, M.; Kawamura, J.; Terauchi, N. Performance Comparison between a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor and an Induction Motor as a Traction Motor for High Speed Train. IEEJ Trans. Ind. Appl. 2006, 126, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.C.; Fodorean, D. Electrical Machines Solutions for Air Conditioning System in Automotive Industry. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference and Exposition on Electrical and Power Engineering (EPE), Iasi, Romania, 20–22 October 2016; pp. 261–266, ISBN 978-1-5090-6128-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yi, F.; Feng, C.; Zhang, C.; Deng, B.; Qi, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. ADRC Control of Ultra-High-Speed Electric Air Compressor Considering Excitation Observation. Actuators 2024, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Peng, X. Performance Assessment and Optimization of the Ultra-High Speed Air Compressor in Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodorean, D. Study of a High-Speed Motorization With Improved Performances Dedicated for an Electric Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, S.; Salazar, M.; Elbert, P.; Bussi, C.; Onder, C.H. Time-optimal Control Strategies for a Hybrid Electric Race Car. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbajit, P.; Pil-Wan, H.; Junghwan, C.; Yon-Do, C.; Jae-Gil, L. State-of-the-art review of railway traction motors for distributed traction considering South Korean high-speed railway. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 14623–14642. [Google Scholar]

- Goli, C.S.; Manjrekar, M.; Essakiappan, S.; Sahu, P.; Shah, N. Landscaping and Review of Traction Motors for Electric Vehicle Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference & Expo (ITEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 21–25 June 2021; pp. 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.S.; Lalitha, M.P. Analysis and Review of Various Motors Used for Electric Vehicle Propulsion. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Smart Systems for applications in Electrical Sciences (ICSSES), Tumakuru, India, 7–8 July 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krings, A.; Monissen, C. Review and Trends in Electric Traction Motors for Battery Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), Gothenburg, Sweden, 23–26 August 2020; pp. 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, H.; Gnanavignesh, R.; Narayanan, G. Review of Traction Standards and Simulation of Traction Power Supply System. In Proceedings of the IEEE India Council International Subsections Conference (INDISCON), Bhubaneswar, India, 15–17 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamuk, M. Review of Electric Vehicle Powertrain Technologies with OEM Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Aegean Conference on Electrical Machines and Power Electronics (ACEMP) & 2019 International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM), Istanbul, Turkey, 27–29 August 2019; pp. 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, S.J.; Ren, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L. Configurations and control of traction motors for electric vehicles: A review. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2017, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintu George, T.; Sahayadhas, A. A Review on Drive Selection, Converters and Control for Electric Vehicle. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd International Conference on Technology, Engineering, Management for Societal Impact Using Marketing, Entrepreneurship and Talent (TEMSMET), Mysuru, India, 10–11 February 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.J.; Juliha, J.L.; Josh, F.T. Review on the recent development of the power converters for electric vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 19–20 October 2017; pp. 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, C.S.; Essakiappan, S.; Sahu, P.; Manjrekar, M.; Shah, N. Review of Recent Trends in Design of Traction Inverters for Electric Vehicle Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Chicago, IL, USA, 28 June–1 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, M.L.; Saha, A.K. A Comprehensive Review of Advanced Traction Motor Control Techniques Suitable for Electric Vehicle Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 125080–125108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, S.J.; Jamil, M.; Amjad, A. Electric Motors and Speed Sensorless Control for Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicles: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2018 53rd International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Glasgow, UK, 4–7 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.; Savitski, D.; Shyrokau, B. A Survey of Traction Control and Antilock Braking Systems of Full Electric Vehicles with Individually Controlled Electric Motors. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 64, 3878–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, P.; Vasan, P.V. Review on Energy Management System of Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Power and Embedded Drive Control (ICPEDC), Chennai, India, 21–23 August 2019; pp. 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Schubert, E.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Bobba, D.; Sarlioglu, B. Overview of Electric Turbocharger and Supercharger for Downsized Internal Combustion Engines. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2017, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, C.; Marsano, D. Instability Phenomena in Centrifugal Compressors and Strategies to Extend the Operating Range: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Peng, X. A review of key components of hydrogen recirculation subsystem for fuel cell vehicles. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 15, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Reinforcement Learning Based Energy Management Strategy for Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 38, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Yi, F.; Wang, G.; Pan, C.; Guo, W.; Shu, X. Research on Energy Management of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Bus Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning Considering Velocity Control. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, L.; Hakari, T.; Matsui, Y.; Deguchi, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Inoue, M.; Ishikawa, M. Understanding the improved performances of Lithium–Sulfur batteries containing oxidized microporous carbon with an affinity-controlled interphase as a sulfur host. J. Power Sources 2024, 624, 235572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.topspeed.com/why-toyota-mirai-alive-despite-poor-sales/#:~:text=Ever%20since%20its%20introduction%20in%202015%2C%20Toyota%20has,including%202%2C737%20examples%20in%202023%2C%20according%20to%20CarFigures (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Bao, H.; Fu, J.; Sun, X.; Sun, C.; Kuang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Performance prediction of the centrifugal air compressor for fuel cells considering degradation characteristics based on the hierarchical evolutionary model. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 46, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, G. Research to the strength of High Speed Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. In Proceedings of the 2021 24th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 31 October–3 November 2021; pp. 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durantay, L.; Velly, N.; Pradurat, J.-F.; Chisholm, M. New Testing Method for Large High-Speed Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbir, F. Vehicles with Hydrogen-Air Fuel Cells. Energy Carr. Convers. Syst. 2008, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Klütsch, J.; Pischinger, S. Systematic Design of Cathode Air Supply Systems for PEM Fuel Cells. Energies 2024, 17, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plait, A.; Saenger, P.; Bouquain, D. Fuel Cell System Modeling Dedicated to Performance Estimation in the Automotive Context. Energies 2024, 17, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaelst, R.; Begerow, D.; Timmann, K.B.; Liebe, T.K. Experimental Methods for Evaluating Components of Turbomachinery, for Use in Automotive Fuel Cell Applications. Machines 2022, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunier, B.; Miraoui, A. Air Management in PEM Fuel Cells: State-of-the-Art and Prospectives. In Proceedings of the ACEMP ’07 International Aegean Conference on Electrical Machines and Power Electronics, Bodrum, Turkey, 10–12 September 2007; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Schödel, M.; Menze, M.; Seume, J.R. Numerical Investigation of a Centrifugal Compressor with Various Diffuser Geometries for Fuel Cell Applications. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Turbomachinery Fluid Dynamics & Thermodynamics, ETC2021-686, Gdansk, Poland, 12–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capata, R. Experimental Fitting of Redesign Electrified Turbocompressor of a Novel Mild Hybrid Power Train for a City Car. Energies 2021, 14, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, P.; Burke, R.; Zhang, Q.; Copeland, C.; Stoffels, H. Electric Turbocharging for Energy Regeneration and Increased Efficiency at Real Driving Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoedel, M.; Menze, M.; Seume, J.R. Experimentally Validated Extension of the Operating Range of an Electrically Driven Turbocharger for Fuel Cell Applications. Machines 2021, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Mei, J.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; Yang, W.; Zhuo, R.; Song, K. Self-Tuning Oxygen Excess Ratio Control for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells Under Dynamic Conditions. Processes 2024, 12, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Guoyu, C.; Xiaodong, S.; Zebin, Y.; Yeman, F. Performance optimization design and analysis of bearingless induction motor with different magnetic slot wedges. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerada, D.; Mebarki, A.; Brown, N.L.; Bradley, K.J.; Gerada, C. Design Aspects of High-Speed High-Power-Density Laminated-Rotor Induction Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 4039–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, A.; Asama, J. Influence of Rotor Skew in Induction Type Bearingless Motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 4646–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, F.; Gao, Y. Optimization of an Asymmetric-Rotor Permanent Magnet-Assisted Synchronous Reluctance Motor for Improved Anti-Demagnetization Performance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degano, M.; Carraro, E.; Bianchi, N. Selection criteria and robust optimization of a traction PM-assisted synchronous reluctance motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 4383–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raminosoa, T.; Blunier, B.; Fodorean, D.; Miraoui, A. Design and Optimization of a Switched Reluctance Motor Driving a Compressor for a PEM Fuel-Cell System for Automotive Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 57, 2988–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, G.F.; Hieu, P.T.; Jeong, K.-I.; Ahn, J.-W. Characteristics Analysis and Comparison of High-Speed 4/2 and Hybrid 4/4 Poles Switched Reluctance Motor. Machines 2018, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, J.H.J.; Marquez-Fernandez, F.J.; Fraser, A.G.; McCulloch, M.D. Performance evaluation of a high speed segmented rotor axial flux switched reluctance traction motor. In Proceedings of the XXII International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), Lausanne, Switzerland, 4–7 September 2016; pp. 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Feng, M.; Liu, J.; Du, R. Multi-Physical Field Analysis and Optimization Design of the High-Speed Motor of an Air Compressor for Hydrogen Oxygen Fuel Cells. Energies 2024, 17, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupertino, F.; Leuzzi, R.; Monopoli, V.G.; Cascella, G.L. Design Procedure for High-Speed PM Motors Aided by Optimization Algorithms. Machines 2018, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-W.; Koo, M.-M.; Seo, H.-U.; Lim, D.-K. Optimizing the Design of an Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for Electric Vehicles with a Hybrid ABC-SVM Algorithm. Energies 2023, 16, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.-S.; Kim, J.-M.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Hong, J.-P. Design of an Ultra-High-Speed Permanent-Magnet Motor for an Electric Turbocharger Considering Speed Response Characteristics. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-W.; Hong, D.-K. Rotor Design, Analysis and Experimental Validation of a High-Speed Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for Electric Turbocharger. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21955–21969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdana, V.; Bulic, N.; Gruber, W. Topology Choice and Optimization of a Bearingless Flux-Switching Motor with a Combined Winding Set. Machines 2018, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Niu, S. Flux-Modulated Permanent Magnet Machines: Challenges and Opportunities. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaz, M.R.; Celebi, M. Design and analysis of a new axial flux coreless PMSG with three rotors and double stators. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Kou, B.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H. Electromagnetic Design of a Dual-Consequent-Pole Transverse Flux Motor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Du, H.; Lei, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. Design and Analysis of Modular Permanent Magnet Claw Pole Machines With Hybrid Cores for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangdehi, S.M.K.; Abdollahi, S.E.; Gholamian, S.A. Analysis of a Novel Transverse Laminated Rotor Flux Switching Machine. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2018, 33, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derban, M.-S.; Fodorean, D. A Study of a 7.5 kW and 18,000 r/min Synchronous Reluctance Motor for Fuel Cell Compressor Applications. Eng. Proc. 2024, 79, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodorean, D.; Idoumghar, L.; Brevilliers, M.; Minciunescu, P.; Irimia, C. Hybrid Differential Evolution Algorithm employed for the Optimum Design of a High-Speed PMSM used for EV Propulsion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 9824–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.C.; Fodorean, D. Design and performances evaluation of a high speed induction motor used for the propulsion of an electric vehicle. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, Ischia, Italy, 18–20 June 2014; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendershot, J.R. Tutorial: Electric Machine Design Strategies to Achieve IE2, IE3 & HEM (IE4) Efficiencies. In Proceedings of the ICEM 2014, Berlin, Germany, 2–5 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Artudean, D.; Kertész, N.; Popa, D.-C.; Bacali, L.; Szabó, L. Navigating Supply Chain Shortages in the Transition to Sustainable Transportation: The Role of Critical Materials Beyond Batteries. Eng. Proc. 2024, 79, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhua, F.; Huan, L. High Power Density PMSM with Lightweight Structure and High-Performance Soft Magnetic Alloy Core. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 0602805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Sun, R.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Tang, R. Loss and Thermal Analysis of a High-Speed Surface-Mounted PMSM With Amorphous Metal Stator Core and Titanium Alloy Rotor Sleeve. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.A.; Hsieh, M.-F. Improvement of Traction Motor Performance for Electric Vehicles Using Conductors with Insulation of High Thermal Conductivity Considering Cooling Methods. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 8202405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, J.; Steinborn, G.; Hofmann, W. Torque, Power, Losses, and Heat Calculation of a Transverse Flux Reluctance Machine With Soft Magnetic Composite Materials and Disk-Shaped Rotor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballestin-Bernad, V.; Kulan, M.C.; Baker, N.J.; Dominguez-Navarro, J.A. Power Analysis in an SMC-Based Aerospace Transverse Flux Generator for Different Load and Speed Conditions. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Di Leonardo, L.; Fabri, G.; Volpe, G.; Riviere, N.; Villani, M. Design of Induction Motors with Flat Wires and Copper Rotor for E-Vehicles Traction System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 3889–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Ebizuka, R.; Yasunaga, A. Rotor design for high efficiency induction motors for railway vehicle traction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 15–18 November 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selema, A.; Ibrahim, M.N.; Sergeant, P. Development of Novel Semi-Stranded Windings for High Speed Electrical Machines Enabled by Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.S.; Alvarenga, B.P.; Paula, G.T. Electrical Machine Winding Performance Optimization by Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Algorithm. Energies 2024, 17, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams Ghahfarokhi, P.; Podgornovs, A.; Cardoso, A.J.M.; Kallaste, A.; Belahcen, A.; Vaimann, T. Hairpin Windings for Electric Vehicle Motors: Modeling and Investigation of AC Loss-Mitigating Approaches. Machines 2022, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, D.; Messager, G.; Binder, A. 1 kW/60,000 min−1 bearingless PM motor with combined winding for torque and rotor suspension. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-W.; Hong, D.-K. Electrical and Mechanical Characteristics of a High-Speed Motor for Electric Turbochargers in Relation to Eccentricity. Energies 2021, 14, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.; Zheng, L. Design and Control of a High-Speed Motor and Generator Unit for Electric Turbocharger (E-Turbo) Application. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Detroit, MI, USA, 19–21 June 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.-W.; Seo, U.-J.; Paul, S.; Chang, J. Computationally efficient stator AC winding loss analysis model for traction motors used in high-speed railway electric multiple unit. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28725–28738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubas, F.; Espanet, C.; Miraoui, A. Field Diffusion Equation in High-Speed Surface Mounted Permanent Magnet Motors, Parasitic Eddy-Current Losses. In Proceedings of the ELECTROMOTION Conference, Lausanne, Switzerland, 27–29 September 2005; pp. 1–6, hal-00322441. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S.; Michon, M.; Popescu, M.; Volpe, G. Optimisation of Hairpin Winding in Electric Traction Motor Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Hartford, CT, USA, 17–20 May 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannier, A.; Di Bruno, F.; Fiume, F.; Fedele, E.; Brando, G. Hairpin Winding Technology for Electric Traction Motors: Design, Prototyping, and Connection Rules. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), Valencia, Spain, 5–8 September 2022; pp. 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, W.; Hua, W. Research on Stator Iron Loss of Ultra-high-speed Permanent Magnet Motor for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Air Compressor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific), Haining, China, 28–31 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodorean, D.; Viorel, I.A.; Djerdir, A.; Miraoui, A. Performances for a Synchronous Machine with Optimized Efficiency while Wide Speed Domain is Attempted. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2008, 2, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yi, F.; Hu, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Load Torque Component Extraction and Analysis of Ultra-High-Speed Electric Air Compressors for Fuel Cell Vehicles. Actuators 2024, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepsu, D.; Jastrzebski, R.P.; Pyrhönen, O. Modeling of a 30 000 Rpm Bearingless SPM Drive With Loss and Thermal Analyses for a 0.5 MW High-Temperature Heat Pump. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 6965–6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.M.; Jung, Y.-H.; Lim, M.-S. Design of Ultra-High-Speed Motor for FCEV Air Compressor Considering Mechanical Properties of Rotor Materials. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 2850–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-R.; Sun, J.; Dobbs, H.; King, J. Model Predictive Control for Power and Thermal Management of an Integrated Solid Oxide Fuel Cell and Turbocharger System. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Tong, W.; Zhu, J. Cooling System Design of a High-Speed PMSM Based on a Coupled Fluidic–Thermal Model. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 0601405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hao, D.; Tong, W. Cooling System Design and Thermal Analysis of Modular Stator Hybrid Excitation Synchronous Motor. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2022, 6, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.; Strangas, E.G. Cooling Systems for High-Speed Machines—Review and Design Considerations. Energies 2025, 18, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deisenroth, D.C.; Ohadi, M. Thermal Management of High-Power Density Electric Motors for Electrification of Aviation and Beyond. Energies 2019, 12, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Tai, L.D.; Lee, M.-Y. Numerical Study on the Heat Transfer Characteristics of a Hybrid Direct–Indirect Oil Cooling System for Electric Motors. Symmetry 2025, 17, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, S.; Sang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, B.; Thrassos, P.; Romeos, A.; Giannadakis, A. Spray Cooling as a High-Efficient Thermal Management Solution: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodorean, D.; Idoumghar, L.; N’diaye, A.; Bouquain, D.; Miraoui, A. Simulated Annealing Algorithm for the Optimisation of an Electrical Machine. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2012, 6, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknejad, P.; Agarwal, T.; Barzegaran, M.R. Utilizing Sequential Action Control Method in GaN-Based High-Speed Drive for BLDC Motor. Machines 2017, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ahn, J.; Jeong, S.; Park, Y.-G.; Kim, H.; Cho, D.; Hwang, S.-H. Driving Control Strategy and Specification Optimization for All-Wheel-Drive Electric Vehicle System with a Two-Speed Transmission. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, J.; Maucec, M.S.; Boskovic, B. Differential evolution algorithm for single objective bound-constrained optimization: Algorithm j2020. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC 2020), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fodorean, D.; Idoumghar, L.; Szabo, L. Motorization for electric scooter by using permanent magnet machines optimized based on hybrid metaheuristic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2013, 62, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.W.; Hadi, A.A.; Mohamed, A.K.; Awad, N.H. Evaluating the performance of adaptive gaining sharing knowledge based algorithm on CEC 2020 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC 2020), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar Misra, R.; Singh, D. Improving the local search capability of effective butterfly optimizer using covariance matrix adapted retreat phase. In Proceedings of the IEEE congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC 2017), Donostia, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 1835–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Ravinath, G.; Pushpa Latha, P.; Priya, L.; Ramesh, J. Optimizing and Analyzing a Centrifugal Compressor Impeller for 50,000 rpm: Performance Enhancement and Structural Integrity Assessment. Eng. Proc. 2023, 59, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, N.H.; Ali, M.Z.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble sinusoidal differential covariance matrix adaptation with Euclidean neighborhood for solving CEC 2017 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC 2017), Donostia, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, C.V.; Essaid, M.; Idoumghar, L.; Fodorean, D. Novel Differential Evolutionary Optimization Approach for an Integrated Motor-Magnetic Gear used for Propulsion Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 142114–142128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, X.Z.; Martin, J.J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Wu, S.; Merida, W. A review of PEM fuel cell durability: Degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandesris, M.; Vincent, R.; Guetaz, L.; Roch, J.-S.; Thoby, D.; Quinaud, M. Membrane degradation in PEM fuel cells: From experimental results to semi-empirical degradation laws. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 8139–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, T.; Pei, P.; Liang, C. A review of durability test protocols of the proton exchange membrane fuel cells for vehicle. Appl. Energy 2018, 224, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, R.Z.; Zhao, W.; Chen, G.; Chai, M.R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Recent research progress in PEM fuel cell electrocatalyst degradation and mitigation strategies. EnergyChem 2021, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu-Zagar, C.; Notingher, P.V.; Cristina, S. Ageing and Degradation of Electrical Machines Insulation. J. Int. Sci. Publ. Mater. Methods Technol. 2014, 8, 526–546. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:53612410 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Bian, C.; Yang, S.; Huang, T.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zio, E. Performance Degradation Assessment for Electrical Machines Based on SOM and Hybrid DHMM. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.02342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, M.; Malec, D.; Maussion, P.; Manfé, P. Design of Experiments Predictive Models as a Tool for Lifespan Prediction and Comparison for Enameled Wires Used in Low-Voltage Inverter-Fed Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 3100–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.; D’Amato, D.; Leuzzi, R.; Monopoli, V.G. Analysis of Electrical Aging Effects on AC High Frequency Motor Based on Exchange Market Algorithm Model Parameter Identification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 32753–32761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Liu, S.; Kang, J. Degradation Mechanism and Online Electrical Monitoring Techniques of Stator Winding Insulation in Inverter-Fed Machines: A Review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balitskii, A.I.; Kolesnikov, V.O.; Havrilyuk, M.R.; Balitska, V.O.; Ripey, I.V.; Królikowski, M.A.; Pudlo, T.K. Steel Hydrogen-Induced Degradation Diagnostics for Turbo Aggregated Rotor Shaft Repair Technologies. Energies 2025, 18, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhayeu, P.; Dybiński, O.; Majewska, K.; Martsinchyk, A.; Łazor, M.; Martsinchyk, K.; Szczęśniak, A.; Milewski, J. Degradation and Corrosion of Metal Components in High-Temperature Fuel Cells and Electrolyzers: Review of Protective Approaches. Energies 2025, 18, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirnovan, R.; Giurgea, S.; Miraoui, A.; Cirrincione, M. Surrogate modelling of compressor characteristics for fuel-cell applications. Appl. Energy 2008, 85, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Boua, J. Contribution à la Modélisation et au Contrôle de Compresseurs. Application à la Gestion de l’Air Dans les Systèmes Piles à Combustible de Type PEM. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology from Belfort Montbeliard, Montbeliard, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barbir, F. PEM Fuel Cells, Theory and Practice; EG&G Technical Services; Fuel Cell Handbook; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Bao, H.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Review of recent developments in fuel cell centrifugal air compressor: Comprehensive performance and testing techniques. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 30, 32039–32055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Xue, R.; Wu, Q.; Wang, B.; Fang, M.; Ruan, Q.; Liu, W.; Ren, Y. Polarization-Selective Dynamic Coupling: Electrorotation-Orbital Motion of Twin Colloids in Rotating Fields. Electrophoresis 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Tu, L.; Ren, Y. Alternating-current induced-charge electrokinetic self-propulsion of metallodielectric Janus particles in confined microchannels within a wide frequency range. J. Appl. Phys 2025, 138, 184702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antivachis, M.; Dietz, F.; Zwyssig, C.; Bortis, D.; Kolar, J.W. Novel High-Speed Turbo Compressor With Integrated Inverter for Fuel Cell Air Supply. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 6, 612301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zuo, S.; Wu, Z.; Liu, C. Dynamic Modeling of Fuel Cell Air Management System and Influence Analysis of Motor Torque Ripple; SAE Technical Paper 2022-01-0695; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X. A Reliable and Efficient I-f Startup Method of Sensorless Ultra-High-Speed SPMSM for Fuel Cell Air Compressors. Actuators 2024, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher-Chong, E.; Ayubirad, M.A.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, H.; Goshtasbi, A.; Ossareh, H.R. Hierarchical Fuel-Cell Airpath Control: An Efficiency-Aware MIMO Control Approach Combined With a Novel Constraint-Enforcing Reference Governor. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2024, 32, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peng, B.; Zhu, B. Performance Analysis and Test Research of PEMFC Oil-Free Positive Displacement Compressor for Vehicle. Energies 2021, 14, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application | Average Speed (r/min) | Average Torque (Nm) | Application Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starter-Generator (SG) | 100 | 300 | the best power-density is requested, usually obtained with expensive materials and water cooling |

| Electro-Hydraulic Active Suspension (EHAS) | 500 | 10 | high-density currents requested, while coreless solutions are to be employed |

| Electric Power Assisted Steering (EPAS) | 800 | 9.5 | the best power-density is requested, usually obtained with expensive materials |

| Variable Valve Timing (VVT) | 1000 | 7 | high-temperature capability is requested, with artificial cooling |

| Electric Gearbox (EG) | 1000 | 250 | high-density water-cooled poli-phased motors needed, with 3D core materials |

| Electro-Mechanical Active Suspension (EMAS) | 4000 | 95 | higher speed and power density, usually obtained with expensive materials |

| Electric Assisted Front Steering (EAFS) | 6500 | 1 | high-speed and high-current density motors with rare earth materials |

| Hybrid Vehicle propulsion (HV) | 9000 | 250 | maximized propulsion speed, water cooled and pin-type winding, with limited rare earth material |

| Electric Vehicle propulsion (EV) | 11,000 | 400 | maximized propulsion speed, water cooled and pin-type winding, with limited rare earth material |

| Fuel Cell Air-Compressor (FCAC) | 20,000 | 10 | maximized speed, water cooled, decreased magnetic poles and frequency, mechanical stress |

| Heating, Ventilation, Air-Conditioning (HVAC) | 40,000 | 6 | maximized speed, water cooled, decreased magnetic poles and frequency, mechanical stress |

| Electric Assisted Turbochargers (EATC) | 80,000 | 1 | maximized speed, water cooled, decreased magnetic poles and frequency, mechanical stress |

| Parameter | HS-SynRM1 | HS-SynRM2 | HS-SynRM3 | HS-SynRM4 | HS-SynRM5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase current (A, rms) | 18 | ||||

| Winding factor (--) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Average torque (Nm) | 3.98 | ||||

| Torque ripple (%) | 42.85 | 28.96 | 27.66 | 16.07 | 28.12 |

| Active part weight (kg) | 7.69 | 8.01 | 8.75 | 11.16 | 8.90 |

| Active part cost for raw material (EUR) | 41.85 | 42.39 | 44.60 | 59.06 | 44.75 |

| Parameter | Mean Torque (N·m) | Torque Ripples (%) | Stator Iron Loss (W) | Rotor Iron Loss (W) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine | |||||

| Parallel magnetization | |||||

| HS-PMSM1 | 8.41 | 10.69 | 310.46 | 7.68 | |

| HS-PMSM2 | 8.35 | 6.56 | 304.21 | 8.26 | |

| HS-PMSM3 | 7.93 | 3.45 | 281.50 | 8.24 | |

| Radial magnetization | |||||

| HS-PMSM1 | 9.04 | 5.57 | 339.46 | 12.91 | |

| HS-PMSM2 | 8.80 | 5.11 | 334.28 | 12.90 | |

| HS-PMSM3 | 8.70 | 2.49 | 298.61 | 12.32 | |

| Material | Property | Value (Unit) | Material Density (kg·m−3) | Cost (€·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| air | magnetic permeability | 1.2566·10−6 (m·kg·A−2·s−2) | 0.9996 (at 90 °C) | - |

| copper | electric resistivity | 2.438·10−8 (Ω·m) | 8954 | 8 |

| Young’s modulus | 130 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.343 | |||

| aluminum | electric resistivity | 2.65·10−8 (Ω·m) | 2700 | 5 |

| Young’s modulus | 77 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.33 | |||

| Nd-Fe-B magnet | remanent flux density | 1.15 T (at 160 °C) | 7400 | 70 |

| magnetic field coercitivity | 907 (kA·m−1) | |||

| relative magnetic permeability | 1.05 | |||

| Young’s modulus | 150 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | |||

| Sm-Co magnet | remanent flux density | 1.1 T (at 160 °C) | 8300 | 80 |

| magnetic field coercitivity | 1000 (kA·m−1) | |||

| relative magnetic permeability | 1.04 | |||

| Young’s modulus | 150 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | |||

| M530 steel | flux density saturation limit | 1.8 (T) | 7800 | 3 |

| sheet stack coefficient (0.35 mm) | 0.97 | |||

| Young’s modulus | 210 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | |||

| Vacoflux48/Vacodur50 | flux density saturation limit | 2.2 (T) | 8120 | ~100 |

| sheet stack coefficient (0.2 mm) | 0.95 | |||

| Young’s modulus | 150 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | |||

| Somaloy steel | flux density saturation limit | 1.6 (T) | 7800 | 30 |

| stack coefficient | 1 | |||

| Young’s modulus | 170 (GPa) | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.23 | |||

| Titanium alloy | Young’s modulus | 114 (GPa) | 4500 | ~200 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.34 | |||

| Epoxy resin | Young’s modulus | 5 (GPa) | 1300 | ~20 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.4 |

| Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|

| RMS phase emf (V) | 143.5 | 144.2 |

| RMS phase current (A) | 190.9 | 191.6 |

| Mean torque (Nm) | 9.14 | 9.13 |

| Torque’s ripples (%) | 32.1 | 32.2 |

| Total iron losses (W) | 4213.9 | 4181.3 |

| Parameter | Cooling Capacity | Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Method | |||

| Free air-cooling | 0.1–0.3 (W/cm2) | Reduced cooling capacity due to very low heat capacity of air [99]. | |

| Forced air-cooling | 0.5–1.5 (W/cm2) | Limited cooling capacity due to small surface area and air drag [99]. | |

| Water jacket cooling | 1–10 (W/cm2) | Very good cooling capability [100]. | |

| Oil (spray or jet) cooling | 0.75 (W/cm2·K) | 15–19% improved capability with respect to water cooling [101]. | |

| Direct liquid cooling (embedded channels) | 10–40 (W/cm2) | Most effective method for high-speed electrical machines [99]. | |

| Spray cooling (high flux) | 50 (W/cm2) | Not recommended for all application, with cooling capability of up to 500 W/cm2—mainly in electronic applications [102]. | |

| Insulation | Mechanical | Thermal | Bearings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Percentage | 56% | 24% | 17% | 3% |

| Aging | Contamination | Discharge | Turns/Bars Movement | Thermal Overloading | Defective Corona Protection | Overvoltage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Percentage | 31% | 25% | 22% | 10% | 7% | 3% | 2% |

| Parameter | HS-PMSM (Figure 7) | HS-IM (Figure 15a) | HS-SynRM (Figure 15b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rated power (kW) | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Rated speed (r/min) | 26,000 | 26,000 | 2600 |

| Phase current (A) | 55 | 60 | 60 |

| Supplying frequency (Hz) | 433 | 437 | 433 |

| Number of stator slots | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Number of magnetic poles | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Stator and rotor steel material | Vacodur 48 | Vacodur 48 | Vacodur 48 |

| Permanent magnet material | SmCo | - | - |

| Rotor bar material | - | Copper | - |

| Stack length (mm) | 135 | 210 | 250 |

| Stator inner diameter (mm) | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| Stator outer diameter (mm) | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Air-gap (mm) | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Torque ripples, non-skewed/skewed (%) | 10.2/1.8 | 11.9/2.1 | 33.7/2.6 |

| Stator iron loss (W) | 203 | 204 | 454 |

| Rotor iron loss (W) | 40 | 50 | 33 |

| Mechanical loss (W) | 274 | 297 | 436 |

| Power factor (--) | 0.849 | 0.925 | 0.884 |

| Efficiency (%) | 95.6 | 91.5 | 88.9 |

| Cooling | water | water | water |

| Inverter losses | low | high | high |

| Manufacturing challenges | Rotor flux barriers | Rotor slots towards air-gap | - |

| Power density (kW/kg) | 2.48 | 1.68 | 1.33 |

| Critical speed (r/min) | 29,000 | 27,300 | - |

| Cost for the active part (€) | 113 | 92 | 69 |

| Considered bearing type | Aerodynamic bearing | Aerodynamic bearing | Aerodynamic bearing |

| Main advantages | Power density and efficiency | Cost, acceptable power density | Cost and robustness |

| Main disadvantages | Cost and robustness, PM demagnetization risk | Robustness and controllability | Power density and efficiency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fodorean, D. High-Speed Electric Motors for Fuel Cell Compressor System Used for EV Application—Review and Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010476

Fodorean D. High-Speed Electric Motors for Fuel Cell Compressor System Used for EV Application—Review and Perspectives. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010476

Chicago/Turabian StyleFodorean, Daniel. 2026. "High-Speed Electric Motors for Fuel Cell Compressor System Used for EV Application—Review and Perspectives" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010476

APA StyleFodorean, D. (2026). High-Speed Electric Motors for Fuel Cell Compressor System Used for EV Application—Review and Perspectives. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010476