1. Introduction

Radiology reports are crucial for diagnosing X-ray images, interpreting disease severity, and identifying anatomical positions [

1]. Analyzing these X-ray records requires substantial expertise and time from radiologists [

2]. In the healthcare system, significant delays have been caused by the increasing demand for medical imaging and the global shortage of qualified radiologists [

3]. Hence, generating automatic radiology reports has emerged as a promising deep learning solution to improve diagnostic efficiency and reduce clinical workload [

4].

Most existing methods adapt the image captioning paradigm with traditional encoder–decoder frameworks to generate radiology reports [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, these approaches produce results that differ from natural image descriptions. Image captioning requires all visual elements to be comprehensively described, whereas radiology diagnosis demands a selective focus on abnormal findings while integrating medical knowledge from detailed reports [

9]. This approach requires models that accurately identify pathological regions and generate clinically precise descriptions of specific findings.

Recently, contrastive learning (CL) has emerged as a robust alternative to image captioning models, learning joint visual–textual representations of medical reports and X-rays [

10]. Unlike traditional supervised approaches, CL applies large-scale multimodal data without extensive manual annotations. Several studies have investigated CL for radiology report generation by adapting encoders pretrained on natural images [

11,

12,

13]. However, this domain adaptation approach faces challenges in medical domains [

14]. Radiology datasets often differ from natural image datasets in content and scale. The domain gap between natural and medical images, combined with the limited medical training data, poses challenges for scaling large pretrained models to the medical domain.

To address data scarcity challenges, prior work has explored augmentation techniques to enhance CL performance [

15]. Although these approaches are efficient, they present several critical limitations. These methods necessitate substantial computational overhead and complex implementation with extensive hyperparameter tuning. Input space augmentation of medical data poses significant semantic integrity risks. Unlike natural images, where geometric transformations or color adjustments preserve semantic meaning, augmenting X-ray images via rotation, cropping, or intensity changes can alter critical diagnostic features, potentially creating misleading training signals [

16]. Furthermore, text augmentation using paraphrasing or synonym replacement can alter clinical meanings and compromise diagnostic accuracy.

In response to these limitations, this work proposes a novel CL framework with feature space interpolation for retrieval (CLFIR) that operates directly on learned embeddings rather than raw inputs. Feature interpolation has been extensively explored in computer vision, with previous work [

17,

18,

19,

20] demonstrating superiority over input space methods across tasks. These studies suggest that feature space transformations better preserve semantics while performing comparably with significantly lower computational cost. However, these techniques have not been thoroughly investigated in CL for radiological applications.

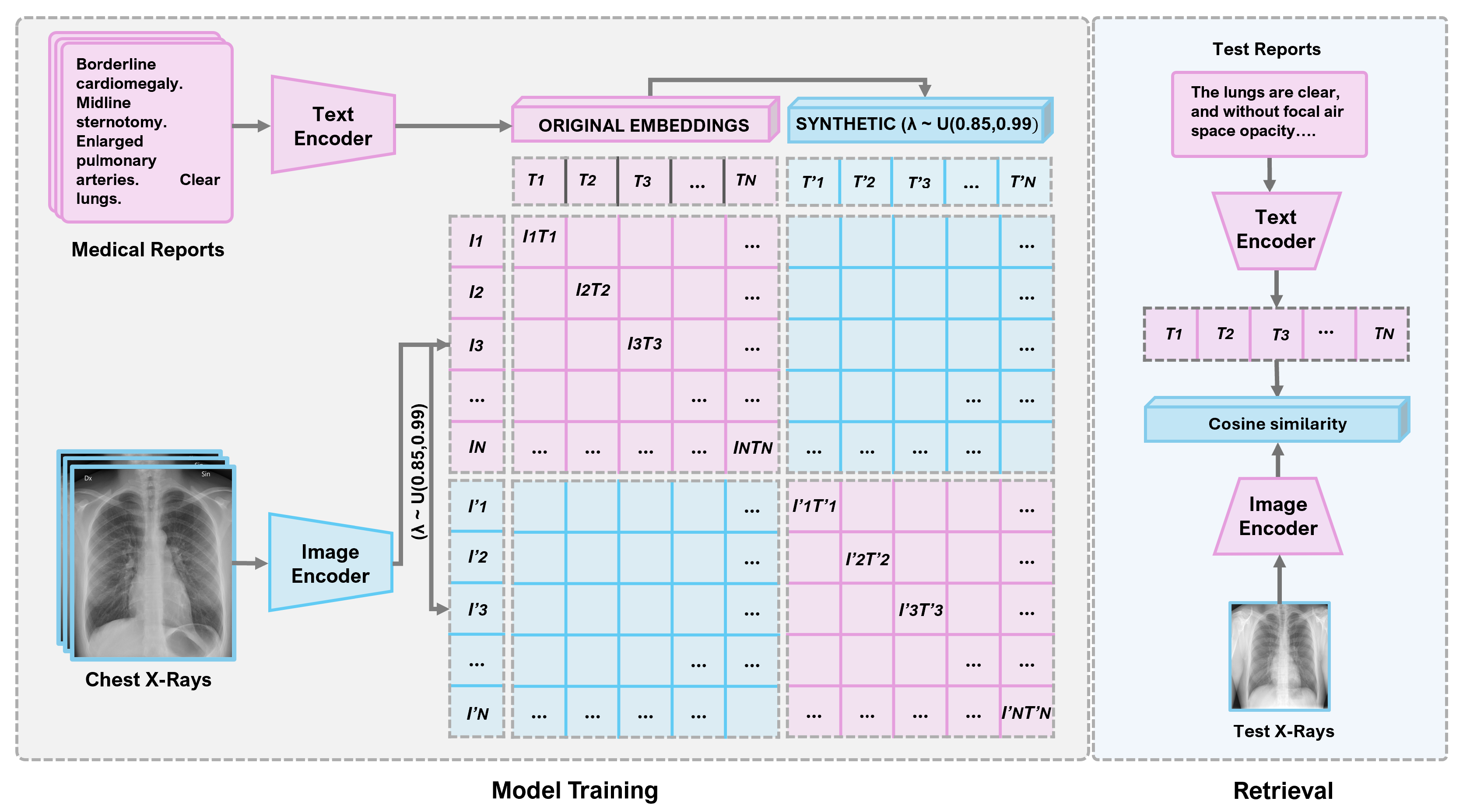

The proposed method operates on learned embeddings to generate an interpolated combination of samples, expanding the training signals while preserving semantic integrity. For each batch of X-ray report embedding pairs, additional mixed pairs are created by combining the original embeddings with shuffled versions from the same batch using a mixing coefficient sampled from a uniform distribution U(0.85, 0.99). This approach maintains consistent cross-modal alignment where the original image embeddings are paired with the original text embeddings, and mixed image embeddings are paired with mixed text embeddings during training. The uniform sampling ensures that interpolated samples retain 85% to 99% of their original semantic content while incorporating 1% to 15% variation from other samples, providing diverse interpolation intensities in each training batch rather than fixed mixing ratios. Therefore, CLFIR avoids the risks associated with input space modifications. The approach creates additional positive and more complex negative pair samples for CL while establishing smoother embedding manifolds that improve model generalization. The major contributions of this work are as follows:

(1) Novel Feature Space Interpolation for Contrastive Vision-Language Pretraining in Data-Scarce Medical Domains: This work introduces CLFIR, which operates directly on learned embeddings, unlike general-domain mixup or input space augmentations that risk diagnostic distortions in sensitive X-ray data.

(2) Batch Expansion and Manifold Smoothing for Enhanced Generalization: By shuffling and interpolating embeddings in mini-batches, CLFIR doubles positive/negative pairs (to 2× per update), mitigating the large-batch requirement of CL image pretraining (CLIP)-style models on small medical corpora. This approach smooths the embedding manifold (by generating intermediate samples between the existing data points), reducing overfitting and improving robustness to rare pathologies.

(3) Superior Computational Efficiency Without Sacrificing Diagnostic Integrity: The CLFIR framework eliminates the overhead of input space augmentations, making it practical for resource-constrained clinical environments while preserving semantic consistency.

(4) State-of-the-Art (SOTA) Performance Across Multiple Tasks: Extensive evaluations on the Indiana University (IU) X-ray and MIMIC-CXR datasets yield new benchmarks in report generation (BLEU-1: 0.51/0.45, ROUGE-L: 0.40/0.34, METEOR: 0.26/0.22), image-to-text retrieval (R@1: 4.14%/24.3%), and zero-shot classification (0.65 accuracy on CheXpert5×200), outperforming prior contrastive and generative methods.

3. Results

3.1. Datasets

This study applies two widely recognized benchmark datasets for a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed CLFIR approach: IU-Xray [

22] and MIMIC-CXR [

23]. Both datasets offer essential resources for training and evaluating medical image–text models.

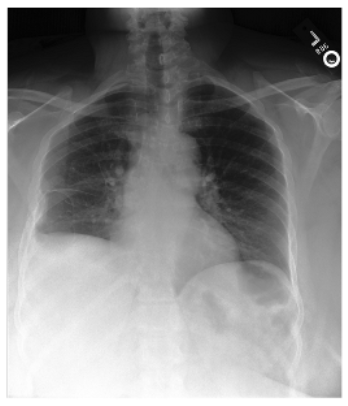

IU X-ray Dataset: This dataset is publicly accessible and comprises 3955 anonymized radiology reports paired with 7470 posterior–anterior and lateral-view chest X-ray images. Each radiology report contains structured sections, including medical subject headings (MeSH), clinical indications, comparative analysis, detailed findings, and diagnostic impressions. For experiments, this work focuses on the findings sections for the ground-truth reference text, given its direct correspondence to observable radiological features. The dataset was carefully filtered to remove incomplete records lacking X-ray images or findings sections. This work adopts the established data partitioning strategy from prior SOTA research, implementing a 7:1:2 split for training, validation, and testing phases while ensuring no patient overlap across partitions.

MIMIC-CXR Dataset: This dataset constitutes a large-scale medical imaging repository with 377,110 chest X-ray images and 227,827 free-text radiology reports covering 65,379 unique patients. This comprehensive dataset originates from clinical studies conducted at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2011 and 2016. Following the established preprocessing protocols, the dataset was filtered to include only frontal and lateral view images, consistent with previous research methods. Similar to the IU X-ray dataset, this work focuses on the findings sections for ground-truth references and applies identical text preprocessing procedures. This work adheres to the official dataset split provided by the original dataset curators for experimental validation, ensuring reproducible results that are comparable with the existing literature.

3.2. Implementation Details

The implementation employed a carefully designed dual-encoder architecture optimized for medical image–text CL. The MobileNetV2 image encoder was initialized using ImageNet pretrained weights, with the first convolutional layer adapted for grayscale input via weight averaging, and all layers remained trainable throughout training. The universal sentence text encoder was similarly set as fully trainable from its pretrained checkpoint. Both encoders were fully fine-tuned during training. For the permutation strategy in the feature space interpolation, a new random permutation was generated for each training batch, with the same permutation consistently applied to the image and text embeddings in the batch to maintain correspondence. Regarding the batch size sensitivity, smaller batch sizes negatively influenced performance due to insufficient negative samples for effective CL. Larger batch sizes (e.g., 150) improved performance on the MIMIC-CXR dataset, given its scale, whereas the performance of the smaller IU X-ray dataset (about 7000 image-report pairs) degraded with excessively large batches due to insufficient iterations per epoch. A batch size of 150 was set to balance these considerations across both datasets.

Training optimization employed the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of and gradient clipping (max norm ) for training stability. Training proceeded for 30 epochs for the IU X-ray dataset and 50 epochs for the MIMIC-CXR dataset with a batch size of 150, incorporating the learning rate reduction on a plateau (factor ; patience 3), and early stopping was based on the validation accuracy (patience 10) to prevent overfitting. Model selection retained the best weights based on the validation performance.

3.3. Quantitative Results

This work evaluates the proposed CLFIR approach against the established baselines using standard natural language generation metrics for medical report generation and image–text retrieval tasks.

3.3.1. IU X-Ray Results

Table 1 presents the comprehensive evaluation results on the IU X-ray dataset. The CLFIR framework achieved SOTA performance across all evaluation metrics, demonstrating the effectiveness of feature space interpolation in medical CL. The results display progression in model sophistication and performance. Early image captioning models (Show-Tell [

24], Att2in [

25], and AdaAtt [

26]) achieved modest scores across all metrics, with BLEU-1 scores ranging from 0.24 to 0.28. Initially designed for natural image description, these approaches struggle to capture the specialized terminology and diagnostic patterns in medical reports. More recent medical-specific approaches introduced substantial improvements. The R2Gen [

7] method, which introduced memory-driven transformers for radiology, achieved notable gains with a BLEU-1 score of 0.47, nearly doubling the performance of basic captioning models. This improvement underscores the importance of domain-specific architectural designs for medical text generation. Later methods (MGRRG [

27], METransformer [

28], ASGMDN [

29], and RRGLKM [

30]) achieved incremental improvements, reaching BLEU-1 scores of around 0.47 to 0.49. Recent CL approaches demonstrated competitive performance. For example, BLLM [

31] and ATL-CAV [

32], which also employ CL strategies, achieved BLEU-1 scores of 0.49 and 0.48, respectively. Although these approaches employ contrastive methods, they differ from CLFIR in architectural settings.

The CLFIR framework demonstrated significant advances across all metrics. The improvement to 0.51 in the BLEU-1 score represents a 4.1% relative gain over the previously best result, and BLEU-2 advances from 0.33 to 0.35, indicating better capturing of medical phrase patterns. The improvement in the METEOR score from 0.20 to 0.26 is significant, representing a 30% relative improvement. The focus of METEOR on semantic similarity and synonym recognition makes this gain valuable for medical terminology. The F1-score improved from 0.39 to 0.42, indicating enhanced clinical entity detection accuracy. In medical report generation, the F1-score measures the ability of the model to identify and correctly generate clinically relevant terms, making this 7.7% improvement clinically meaningful. The consistent improvements across complementary metrics (BLEU for n-gram precision, ROUGE for content recall, METEOR for semantic alignment, and the F1-score for clinical accuracy) demonstrate that the feature space interpolation of CLFIR enhances multiple aspects of medical report quality.

3.3.2. MIMIC-CXR Results

Table 2 presents the performance of CLFIR on the larger MIMIC-CXR dataset, which includes more diverse cases and complex pathological findings than those in the IU X-ray dataset. The results reveal distinct performance patterns between retrieval-based and generative approaches. Retrieval-based methods (CXR-RePaiR-2 [

13] and CXR-RePaiR-Select [

13]) reveal limited performance with sparse metric coverage. The CXR IRGEN [

12] method achieved the highest scores among retrieval methods with a BLEU-1 score of 0.32 and an F1-score of 0.29.

Generative methods demonstrate considerably better performance across all metrics. The R2Gen [

7] method established a strong baseline with a BLEU-1 score of 0.35 and a METEOR score of 0.14. Advanced medical-specific approaches (ASGMDN [

29] and METransformer [

28]) achieved incremental improvements, reaching BLEU-1 scores of 0.37 to 0.38. The current SOTA generative methods (MGGRRG [

27]) displayed competitive results with a BLEU-1 score of 0.40 and an F1-score of 0.33. Among the CL approaches, ATL-CAV achieved competitive results with a BLEU-1 score of 0.38.

The CLFIR method demonstrated significant advances across all evaluation metrics. The improvement in BLEU-1 to 0.45 over the previously best score of 0.40 (MGGRRG [

27]) indicates superior n-gram matching with ground-truth reports. The improvement in the METEOR score from 0.16 to 0.22 represents a 37.5% relative improvement, the most substantial gain across all metrics. This improvement is crucial for MIMIC-CXR, where the larger vocabulary and more diverse pathological descriptions require robust semantic understanding. The F1-score of 0.34 indicates that CLFIR maintains clinical entity detection accuracy while improving the overall report quality. These results validate that the feature space interpolation strategy of CLFIR scales to large, diverse medical datasets while maintaining the semantic preservation crucial for clinical applications.

3.4. Image-to-Text Retrieval

This work evaluates the performance of the model on image–text retrieval tasks to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. This evaluation demonstrates the quality of the learned multimodal representations and their ability to establish meaningful correspondences between radiological images and their associated reports.

This study assesses image–text retrieval performance using the standard recall@k metric (R@K), which measures the recall of the exact report in the top k retrieved reports for a given query image. This metric is relevant for clinical applications as it reflects the ability to identify the correct diagnostic report among multiple candidates. The experiments are conducted on the MIMIC-CXR and IU X-ray (testing) datasets to ensure a comprehensive evaluation and fair comparison with SOTA approaches.

As demonstrated in

Table 3, CLFIR consistently outperformed SOTA approaches across both datasets on the R@K metric. The improvements are substantial on the MIMIC-CXR dataset, where the proposed approach reached notable gains of 2.7 points in R@1, 6.1 points in R@5, and 7.8 points in R@10 compared with the previously best-performing method (CXR-CLIP). On the IU X-ray dataset, the proposed method demonstrated significant improvements, particularly in R@5 and R@10, with gains of 6.94 and 10.78 points, respectively, over CXR-CLIP.

The superior performance in image-to-text retrieval confirms that the feature space mixup interpolation strategy enhances the quality of learned multimodal representations. The substantial improvements in higher k metrics (R@5 and R@10) suggest that the proposed approach enhances exact matches and the overall semantic similarity ranking between images and reports.

3.5. CheXpert5×200 Zero-Shot Classification Performance

This work presents comprehensive zero-shot classification experiments conducted on the CheXpert5×200 dataset to evaluate the cross-dataset generalizability of the proposed CLFIR framework. The validation offers a more rigorous assessment of model robustness on unseen data by focusing on the five clinically critical conditions from CheXpert5×200 (i.e., atelectasis, cardiomegaly, consolidation, edema, and pleural effusion), representing critical pathologies for automated chest radiograph interpretation. The zero-shot classification method applied pretrained vision and text encoders from MIMIC-CXR training. Classification was performed by computing the cosine similarity between the image and condition text embeddings. For each image, 512-dimensional visual features were extracted using the trained vision encoder. Then, cosine similarity scores were computed between the normalized image embedding and each of the five condition text embeddings. Classification decisions were made by assigning positive labels to conditions with similarity scores above a threshold of 0.5. The CLFIR framework achieved superior cross-dataset performance across the five CheXpert conditions, displaying strong zero-shot generalizability. In

Figure 2, the proposed framework substantially outperformed established vision-language models including ConVIRT [

34], GLoRIA [

33], MedCLIP-ResNet, MedCLIP-ViT [

35], and CXR-CLIP [

11].

To provide deeper insight into the diagnostic capabilities of CLFIR, this work presents a detailed per-condition analysis conducted across the five CheXpert pathologies.

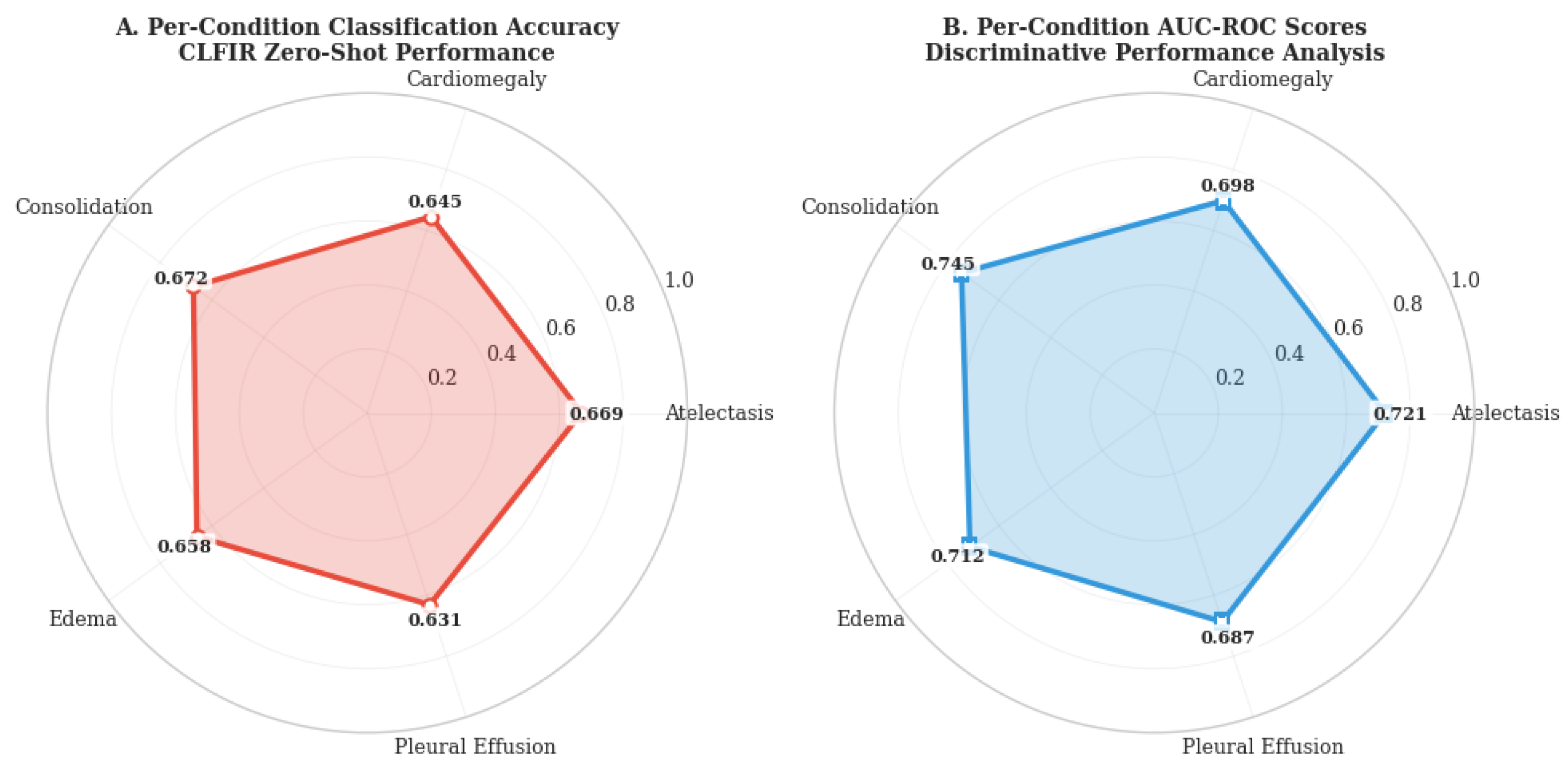

Figure 3 presents the classification accuracy and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) scores for each condition, revealing the granular performance characteristics of the proposed approach.

The CLFIR framework demonstrates consistently robust performance across all five pathologies, with classification accuracy ranging from 0.631 (pleural effusion) to 0.672 (consolidation). The per-condition AUC-ROC scores validate the discriminative capabilities of the model, exhibiting scores between 0.687 and 0.745 across conditions. Notably, CLFIR performs exceptionally well on consolidation (accuracy: 0.672, AUC: 0.745), which is clinically significant because this condition often presents subtle imaging features that challenge automated detection systems.

To contextualize these performance gains,

Table 4 summarizes the critical methodological differences between CLFIR and existing medical vision-language approaches. Although prior methods rely on input space augmentation that may distort diagnostic features, CLFIR operates in the learned embedding space with a negative pairing strategy for interpolated samples. This fundamental difference in the augmentation domain and pairing strategy contributes to the superior zero-shot classification performance of CLFIR.

3.6. Qualitative Results

The qualitative evaluation offers crucial insight into the clinical applicability and semantic coherence of radiological frameworks. Although quantitative metrics measure linguistic similarity, the qualitative analysis indicates whether retrieved reports maintain clinical accuracy and appropriate medical reasoning patterns. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach, this work presents a comprehensive qualitative analysis conducted on the IU X-ray and MIMIC-CXR datasets. This work examines how well the retrieved reports align with ground-truth results in terms of accuracy, focusing on diagnostic completeness and terminology appropriateness.

Table 5 presents examples compared with ground-truth references on both datasets, demonstrating the strong semantic learning capabilities of the proposed model in retrieving clinically relevant and diagnostically accurate reports.

4. Discussion

4.1. Design Validation via Ablation Studies

To further validate the effectiveness of CLFIR, this work presents comprehensive ablation studies examining the critical components and hyperparameters that influence performance. This work systematically analyzes (1) the effect of feature space vs. input space interpolation, (2) the influence of mixing coefficient ranges, (3) computational efficiency comparisons, and (4) the contribution of various interpolation strategies.

4.1.1. Theoretical Justification for Negative Pairing Strategy

A fundamental design in the proposed framework involves treating the combination of original and interpolated pairs to negative during training, requiring theoretical justification. In radiological diagnoses, clinical accuracy demands an exact correspondence between visual pathological findings and textual descriptions. When interpolating , the resulting text embedding contains mixed clinical semantics that may include contradictory diagnostic statements. Unlike natural image–text pairs, where a partial semantic overlap might be acceptable, medical image–text alignment requires diagnostic precision.

A chest X-ray demonstrating specific pathological findings () cannot be correctly paired with a report containing mixed pathological descriptions () because this approach teaches the model to accept clinically inaccurate associations. Furthermore, treating the original interpolated cross-combinations as positive artificially increases positive samples from B to , creating an imbalanced CL scenario with insufficient discriminative signals.

The negative pairing strategy preserves clinical diagnostic integrity while providing challenging negative samples. This approach ensures that the model learns to distinguish between the exact clinical correspondence and mixed pathological descriptions, which is crucial for reliable medical AI systems. To validate this theoretical framework, this work presents comparative experiments conducted between the negative pairing strategy and cross-modal learning approaches, as shown in

Table 6.

The experimental comparison encompasses two distinct pairing strategies. Cross-model learning treats all interpolated combinations as positive pairs, creating

and

as positive samples alongside the original pairs. In contrast, the negative pairing strategy maintains strict positive pairing between semantically consistent samples

and

, while treating cross-combinations

and

as negative samples. As listed in

Table 6, the negative pairing strategy consistently outperformed cross-model learning across all evaluation metrics on both datasets.

4.1.2. Comparison with Alternative Configurations

This work compares CLFIR against multiple baseline configurations to demonstrate the effectiveness of feature space mixup interpolation. All models employed identical encoder architectures optimized for radiology-specific data. CLFIR is evaluated against three baseline configurations: (1) standard CL with no feature space interpolation and no input space augmentation, (2) CL with input space augmentation (random brightness, contrast, and noise adjustments), (3) standard CL with doubled batch size (300) to match the effective training sample count of the feature space interpolation, and the CLFIR approach.

During experimentation, the optimal batch size selection depended on the dataset. For smaller datasets, such as IU X-ray, excessive batch size increases can degrade accuracy due to insufficient batches per epoch. As demonstrated in

Table 7, the proposed CLFIR with feature space interpolation consistently outperformed all baseline configurations, validating that the proposed strategy offers benefits beyond simple batch size increase or input space augmentation.

4.1.3. Comparison with Gaussian Noise Interpolation

To validate CLFIR performance, this work compares Gaussian noise as an alternative feature space interpolation technique. The analysis was conducted on the IU X-ray dataset due to its manageable size for comprehensive hyperparameter exploration, where both datasets exhibited similar radiological characteristics. All experiments applied a fixed random seed (seed = 42) to ensure reproducibility and fair comparison across configurations.

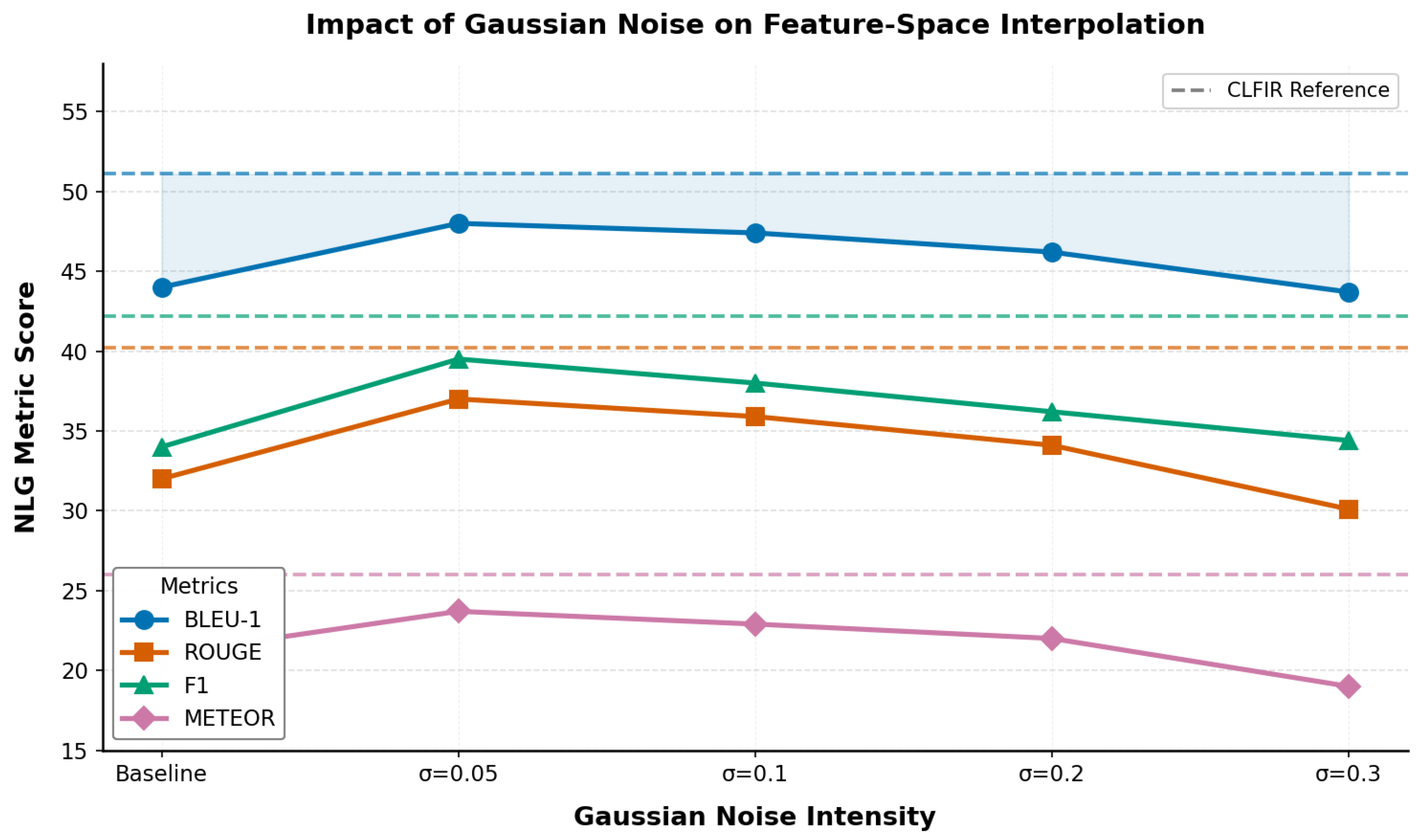

The mixup approach combines embeddings using , ensuring each interpolated sample retains 85% to 99% of its original semantic content while incorporating 1% to 15% from permuted samples. For comparison, this work implements Gaussian noise interpolation by adding random noise to the feature embeddings at varying intensity levels, increasing the feature embedding samples similar to the proposed approach.

The experimental results in

Table 8 demonstrate that the semantic mixup consistently outperformed random noise interpolation across all intensity levels. Although moderate Gaussian noise (

) offers improvement over the baseline, it fails to reach the performance gains of the mixup strategy, which applies semantic relationships between samples rather than random perturbations.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, radiology datasets are sensitive to random perturbations, and semantic preservation via feature space mixing is critical for optimal performance. The degradation with higher noise levels (

) supports the hypothesis that maintaining semantic consistency is critical in medical imaging applications. The visualization reveals the instability of Gaussian noise approaches compared with the robust mixup strategy, which consistently outperformed even the optimal noise configuration.

4.1.4. Optimal Mixup Interpolation Range for CLFIR

To determine the optimal mixup interpolation range for CLFIR, this work presents experiments conducted with various uniform distributions on the IU X-ray dataset. Unlike fixed mixing ratios, the proposed approach samples from uniform distributions, providing variable mixing intensities. This work evaluates four uniform distribution ranges, namely U(0.75,0.99), U(0.80,0.99), U(0.85,0.99), and U(0.90,0.99), where represents the proportion of the original sample retained in the interpolated combination. A fixed random seed (seed = 42) was employed across all configurations to ensure a fair comparison.

As listed in

Table 9, optimal performance was achieved with

U(0.85,0.99), which provides the best balance between preserving the original sample characteristics and introducing beneficial variation.

Figure 5 visualizes these performance trends, demonstrating the superior and consistent performance of U(0.85, 0.99) across all evaluation metrics.

The range ensures that interpolated samples retain 85% to 99% of their original content while incorporating 1% to 15% from shuffled samples. As illustrated in the figure, wider ranges, such as U(0.75, 0.99), introduce excessive variation that could compromise semantic integrity. In contrast, narrower ranges, such as U(0.90, 0.99), offer more conservative mixing, which, while still effective, does not achieve the optimal balance.

This finding indicates that moderate uniform sampling preserves the semantic integrity of medical data while providing sufficient stochastic variation for improved generalization. The uniform distribution approach offers advantages over fixed mixing ratios by delivering diverse interpolation intensities in each batch, preventing the model from overfitting to a single mixing pattern.

4.2. Computational Efficiency Analysis

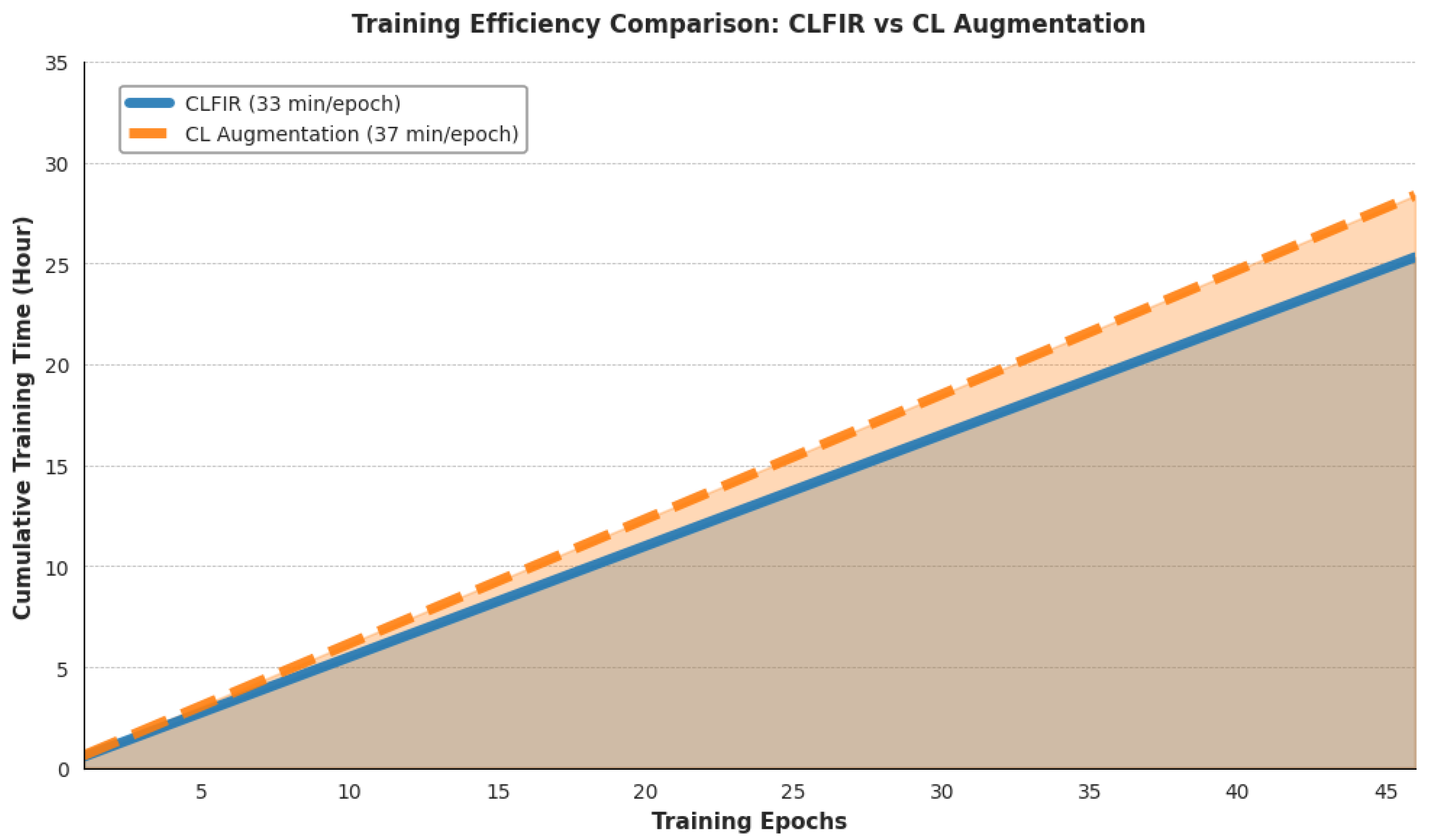

Figure 6 compares the training time on the MIMIC-CXR dataset between CLFIR and the traditional input space image augmentation CL approach. The CLFIR framework requires 33 min per epoch compared to 37 min for input space augmentation methods, representing a 10.8% reduction in training time per epoch. By the end of training, the total training time for CLFIR reaches about 27 h compared to 32 h for augmentation-based approaches, yielding total time savings of 3.3 h. This efficiency gain results from the computational overhead required for input space image augmentation operations. The baseline augmentation process applies random brightness adjustments (±20%), random contrast modifications (±20%), random rotations (±%15°), random cropping and resizing, and Gaussian noise additions (

= 0.01) to each 312 × 312-pixel chest X-ray image during training. These transformations require significant central processing and unit processing time and memory bandwidth for each training batch, creating a computational bottleneck before graphics processing unit-based model training.

In contrast, in CLFIR, feature space interpolation performs simple linear combinations on 512-dimensional embeddings after encoding, eliminating the image preprocessing overhead. The computational savings are even more substantial when text augmentation techniques are included in the baseline because these require additional natural language processing operations, synonym lookup, and text reconstruction processes. The consistent efficiency advantage confirms that feature space interpolation scales favorably for larger datasets while maintaining superior performance, making it more practical for medical imaging research, where computational resources are often limited.

4.3. Synthesis and Limitations

The superior performance of CLFIR across multiple evaluation studies demonstrates its potential to enhance automated radiology report generation. The improvements in METEOR scores on the IU X-ray and MIMIC-CXR datasets compared to previous methods suggest an enhanced semantic understanding of medical terminology, a crucial consideration for medical AI development. Unlike general-purpose image captioning systems that prioritize comprehensive visual descriptions, the proposed approach focuses on pathologically relevant features, aligning with the diagnostic patterns of radiologists. The cross-dataset generalization capabilities (particularly the 65.5% accuracy on CheXpert5×200 zero-shot classification) and SOTA retrieval accuracy demonstrate the robustness of the proposed architecture.

The conservative mixing strategy uses to create interpolated embeddings from the original X-ray and report representations. This approach preserves the diagnostic integrity because interpolation occurs in the learned embedding space rather than modifying raw medical images or text. The negative pairing strategy treats original-interpolated combinations as negative samples during training, ensuring that the model learns to distinguish between exact clinical correspondences and mixed representations.

The substantial performance gaps between CLFIR and input space augmentation methods highlight fundamental differences in how medical and natural image domains respond to data augmentation. Although geometric transformations preserve semantic meaning in natural images, ablation studies confirm that similar operations on radiological images risk altering diagnostically relevant features. The consistent superiority of feature space interpolation across all evaluation metrics validates the hypothesis that learned embedding spaces deliver semantically stable transformation environments. The comparison with Gaussian noise interpolation further reveals the importance of structured semantic relationships in medical data. Random perturbations, regardless of magnitude, fail to achieve the performance gains of the mixup strategy, confirming that structured mixing with intersample relationships outperforms unstructured noise addition.

The computational efficiency demonstrated by CLFIR addresses the computational constraints often encountered in medical imaging research. The elimination of complex input space augmentation processes reduces the computational overhead and hyperparameter tuning requirements. The feature space interpolation increases training samples, mitigating batch size dependencies in CL.

Several limitations require consideration. The evaluation applies standardized benchmark datasets that may not fully represent the variability encountered in clinical practice. Patient demographics (e.g., age and body habitus), imaging acquisition parameters (exposure settings and positioning), and equipment variations across institutions could affect model performance. Although the MIMIC-CXR dataset offers some demographic diversity, a systematic evaluation across patient subgroups (pediatric vs. elderly and different exposure protocols) was not performed. Additionally, the evaluation relies on automated metrics (BLEU, ROUGE, and METEOR) that measure linguistic similarity but do not directly assess clinical correctness. Human radiologists must validate whether generated reports meet clinical standards before future clinical translation.

From a methodological perspective, the mixing coefficient range was empirically optimized for chest X-ray data. Although the principle of conservative interpolation for semantic preservation should generalize across medical imaging modalities, the optimal range may require modality-specific tuning for computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or other imaging types. Furthermore, CLFIR employs global image–text embeddings for retrieval, limiting its interpretability compared with attention-based methods that offer spatial localization of the findings.

Future work should extend the framework to other medical imaging modalities and evaluate its generalizability across healthcare systems. The authors also plan to incorporate human radiologist assessments to validate the clinical reliability and explore region-level CL approaches that could enable spatial attention visualization for improved interpretability.