1. Introduction

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is a prevalent middle ear disease characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the middle ear cavity without signs of acute infection [

1]. It is one of the leading causes of hearing impairment, particularly in children, and is closely associated with delays in speech and language development [

2,

3]. Despite its high prevalence and clinical significance, early and accurate detection of OME remains challenging due to its often subtle and nonspecific clinical presentation. Misdiagnosis or delayed treatment can result in prolonged auditory dysfunction and further complications, highlighting the need for more precise and objective diagnostic tools.

The current standard of care for diagnosing OME includes otoscopy, tympanometry, and audiometry [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Among these, otoscopy remains the most used method in clinical settings; however, it depends on the clinician’s subjective visual interpretation, leading to considerable variability in diagnostic accuracy. The other, non-invasive examinations (such as tympan meter, acoustic reflectometry, and impedance audiometry) have been used to diagnose middle ear status through variation in acoustic characteristics such as pressure, impedance, and absorbance of the reflected signal when the artificially injected sound was reflected through the tympanic membrane [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Recently, smartphone-based analysis of acoustic data and tympanic membrane images using machine-learning methods has also been explored for OME assessment [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Inflammatory processes in the middle ear reduce the volume of the air-filled cavity, resulting in a shift of its resonance frequency toward the higher frequency range [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The stiffness of the tympanic membrane is strengthened by the middle ear effusion that contacts the inner surface of the eardrum, thereby suppressing the plane vibration mode of the membrane. Simultaneously, the transmission and reflection of sound between the middle and external ear through the tympanic membrane is impeded, so the impedance characteristics of the sur-face around the middle ear is dominantly presented in the measured acoustic signal response [

21].

The resonance frequency of the middle ear cavity was predicted based on various variables compensated through conditions of admittance, susceptance, conductance, and phase angle derived through multifrequency tympanometry [

22]. The literature has suggested that the resonance characteristics of the middle ear cavity is expressed in the high frequency band for the medium condition of middle ear. It was confirmed that the resonance characteristics of the middle ear fluctuate at high frequencies due to abnormalities (otosclerosis, effusion) existing inside the middle ear; however, since the resonant frequencies are determined according to the types of variables, an exact criterion has not been established.

Conventional 226 Hz tympanometry is effective in assessing tympanic membrane mobility and detecting the presence of middle ear effusion. Yet, it has limited sensitivity in distinguishing among various middle ear pathologies. To address this, wideband tympanometry (WBT) was developed to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of middle ear mechanics by measuring acoustic reflectance and absorbance over a broad frequency range (typically 250–8000 Hz) [

19,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. While WBT has demonstrated improved diagnostic performance for OME, it remains an indirect method that infers middle ear function from pressure-induced mechanical responses.

To overcome the limitations of current diagnostic modalities, alternative approaches that directly assess middle ear dynamics are being explored. Bone conduction hearing mechanisms provide such a framework, as they bypass the external auditory canal and tympanic membrane to deliver vibrational stimuli directly to the cochlea [

28,

29]. These stimuli propagate through multiple pathways including ossicular chain resonance, cochlear compression, and energy radiation through the tympanic membrane each of which may reflect distinct mechanical characteristics of the middle ear.

Among these methods, vibro-acoustic radiation analysis has recently gained attention as a non-invasive technique for evaluating middle ear mechanics [

30,

31] by measuring the acoustic energy radiated from the tympanic membrane and ossicles during bone-conduction stimulation [

32]. Given that otitis media with effusion (OME) alters the mass, stiffness, and resonance properties of middle ear structures, changes in vibro-acoustic responses may serve as a potential biomarker for effusion detection.

In this study, we propose a simplified structural model of the bone-conduction mechanism to calculate frequency responses associated with signal transmission. By analyzing the variation in middle ear cavity resonance frequency based on the type of middle ear status, subjects were classified into normal and OME groups. Furthermore, we investigate the effects of middle ear abnormalities on tympanic membrane stiffness and elasticity and explore the relationship between these mechanical changes and the acoustic radiation components measured via vibro-acoustic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study enrolled a total of 36 patients diagnosed with otitis media with effusion (OME), who were evaluated at a tertiary referral hospital. The participants ranged in age from 13 to 81 years. A total of 43 ears were included and categorized into two groups for analysis: the OME group (n = 28 ears), which consisted of ears diagnosed with OME, and the control group (n = 15 ears), which included ears from individuals without any middle ear pathology. All patients underwent clinical evaluation and audiological testing, and the diagnosis of OME was confirmed based on comprehensive otoscopic, audiometric, and tympanometry assessments performed by otolaryngologists at the tertiary care center.

2.2. Concepts

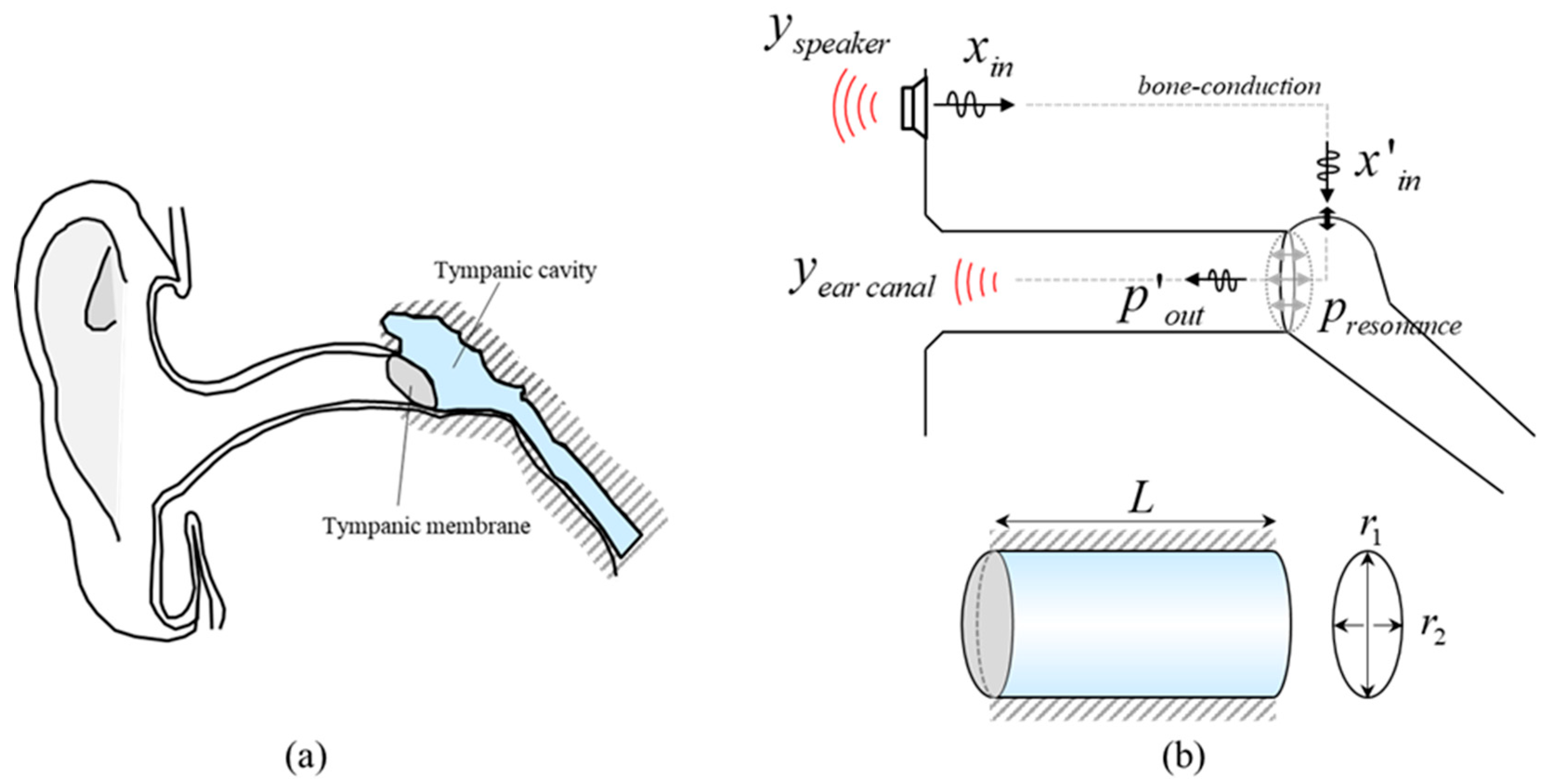

As shown in

Figure 1a, in the vibration wave propagation by bone conduction, the transmission paths related to the vibro-acoustic properties of the wave are referred to as tympanic cavity and tympanic membrane. In the tympanic cavity, not only the vibration of ossicles is converted to the sound, also the amplitude of the signal is amplified by cavity resonance. The tympanic cavity was idealized as an elliptical cylindrical tube representing a typical adult middle-ear cavity. The dimensions were chosen to be consistent with anatomical and radiologic studies reporting adult tympanic cavity sizes and volumes on the order of 500~700 mm

3 [

33]. Although the actual tympanic cavity has an irregular shape and is connected to mastoid air cells, this simplified geometry provides an acoustically reasonable representation of the cavity for analyzing its resonance characteristics. The formula for calculating the cavity resonance of the cylinder structure is as follows:

The first term expressed by the Bessel function in the root of the right equation is the term for the mode elongated to the side, and the second term is related to the longitudinal mode, defined as a function of the pressure

p and the length of the cavity [

34,

35]. The cavity resonance is determined by the combination of the two modes. Since the side surface of the tympanic cavity is in contact with the cranial bone, a fixed boundary condition can be applied. Therefore, the resonance mode for the longitudinal direction will dominate.

Figure 1b is a schematic of the whole process of vibration transmission and conversion of transmitted vibration to sound for the total bone-conduction process. Sound signals generated in the temporal bone by a bone-conduction vibrator are transmitted through the skull and induce motion of the ossicular chain [

36,

37]. This mechanical vibration generates acoustic energy within the middle ear cavity. The signal is selectively amplified at specific frequencies due to the longitudinal resonance characteristics of the tympanic cavity and is subsequently radiated outward through the tympanic membrane, which exhibits broadband resonance properties. The radiated sound then propagates through the external auditory canal and escapes into the surrounding air, and this out-ward radiation from the tympanic membrane–canal system is referred to as the vi-bro-acoustic radiation in this study.

The input random vibrations excited by the bone-conduction vibrator are transmitted through the temporal bone. The response measured in the opposite temporal bone is proportional to the magnitude of the input signal, and the transfer function between the input and the output maintains the same magnitude across despite increasing the input vibration. These observations indicate that, within the tested range, the temporal bone path can be approximated as linear. Therefore, in our framework the bone-conduction pathway up to the middle ear is treated as a linear excitation path, whereas the condition-dependent, nonlinear features of the response are mainly attributed to the middle-ear cavity and tympanic membrane and their vibro-acoustic radiation into the ear canal.

However, when the middle ear is filled with exudative fluid, the processes of sound amplification and acoustic radiation through the tympanic membrane are disrupted. The resulting alterations in acoustic transmission can be identified through frequency-domain analysis. In the present model, these effusion-related changes are not explicitly represent-ed as separate stiffness or damping parameters. Instead, they are treated implicitly and characterized through the differences observed in the measured vibro-acoustic responses between normal and effusive middle-ear conditions.

Unlike reflectometry that rely on the ear-canal quarter-wave resonance, our bone-conduction vibrator operates under different boundary conditions; by contrast, reflectometry captures not only middle-ear responses but also contributions from the external auditory canal and pinna, making it difficult to isolate middle-ear effects and to classify outcomes, which increases variability. Consequently, canal-resonance frequencies around 3–4 kHz do not yield robust group separation and are handled during analysis. Based on these considerations, we analyze condition-dependent features of the acoustic signal that reflect middle ear status.

2.3. Measurements

White Gaussian noise (WGN) refers to a signal with a constant power spectral density in the entire frequency band and has a characteristic of Gaussian distribution whose average is 0 in the time domain. In the field of structural dynamics, impulse signals or WGN signals are applied to structures to analyze the frequency response of the system. The system response extracted from WGN is robust to external noise and is accurate for high-frequency-band analysis.

Figure 2a is an excitation signal that is composed of 5 WGN signal windows whose magnitude increases at a constant rate every 9 s. The response amplitude of each window was constantly below 11,050 Hz. The WGN windows with gradually increasing magnitude were used to confirm that, within the tested range, the bone-conduction excitation path behaved approximately linearly. When the input level was increased, the absolute sound pressure level of the recorded vibro-acoustic radiation also increased, but the overall spectral shape of the response remained stable across windows.

An Aeropex bone-conduction headset (AfterShokz LLC, East Syracuse, NY, USA; model AS800) was used to vibrate the temporal bone by the signal. The instrument can activate signals in the frequency range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. The acoustic signals were acquired at two separate locations using a 2-channel stereo microphone. Through the first channel of the instrument, the sound radiated directly from the bone-conduction speaker was measured as shown in

Figure 2b. It has been confirmed that the boundaries of the windows are clearly divided. The first signal was used as reference data to classify noise factors generated from the distortion of the input signal, the characteristics of the amplifier, and the structural resonance of the speaker. Measurements were conducted near the ear canal to obtain an acoustic signal reflecting the state of the middle ear. For the second channel, the microphone was positioned in front of the external auditory canal opening, without inserting the sensor into the ear canal and without sealing the canal entrance. Thus, the recorded VAR signal corresponds to the sound that escapes from the ear canal into the surrounding free field after being radiated through the tympanic membrane.

Figure 2c showed that the amplitude of the signal tends to increase slightly over time, since the speaker and measuring point are not completely blocked.

During data acquisition, several precautions were taken to reduce the influence of external factors such as ear-canal geometry and head movement on the recorded signals. The probe microphone for the ear-canal measurement was positioned at a consistent distance and orientation in front of the canal opening and kept in the same position throughout each recording. The bone-conduction speaker was firmly coupled to the mastoid using an adjustable headband to minimize relative motion between the transducer and the skull. Subjects were seated comfortably and instructed to keep their head still during the measurements. Recordings showing obvious motion artefacts or abrupt changes in overall level, identified by visual inspection in the time and frequency domains, were discarded prior to further analysis.

Frequency analysis for each window was performed on the same timeline of both signals. Signal processing was performed to deduce the nonlinear phenomenon caused by the middle ear structure and to exclude the linear tendency related to the sound amplification of the window.

2.4. Signal Processing

Fourier transform was applied to the acoustic signal measured in the time domain, and the frequency spectrums of the signals were obtained. Since signals from biological or mechanical systems are measured as synthesized, it is not desirable to classify signal components in the time domain, whereas the Fourier transform can extract and analyze the frequency spectrum of the components from a signal that has numerous frequency characteristics through the orthogonality of a periodic signal. As WGN signals have a uniform power spectral density over all frequency ranges, the characteristics of the system cannot be determined solely by the magnitudes of the frequency components. Rather, it is more appropriate to use the tendency of the response overlapping for any specific frequency band.

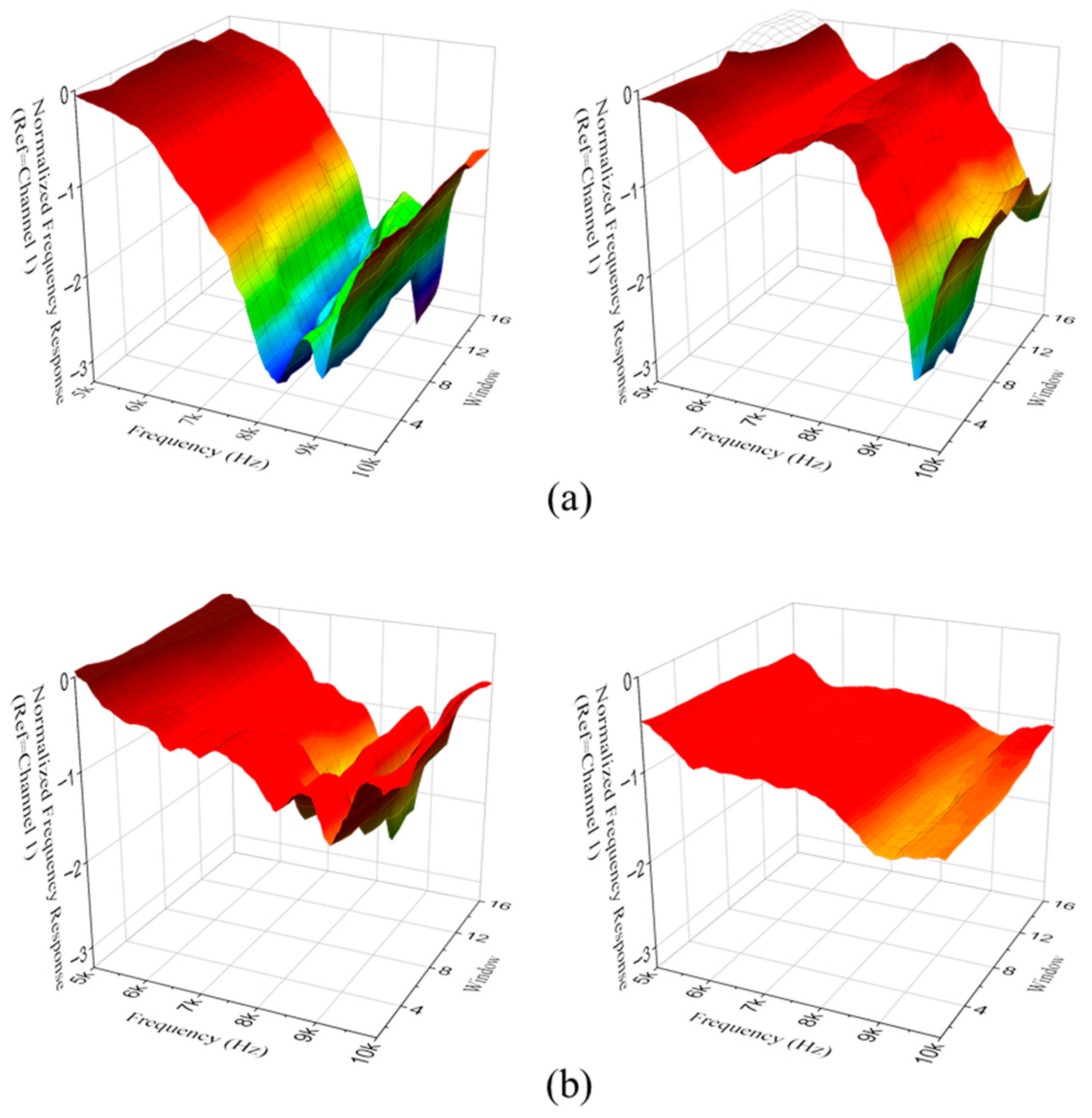

The overlapped spectrum was obtained by applying a band filter of 100 Hz to the measured signal, which was selected as a compromise between spectral resolution and noise reduction. The response was narrow enough to preserve the overall resonance shape, while wide enough to smooth out narrow-band fluctuations and measurement noise that are not relevant for the inspection. When testing is conducted with a normal person as the target, the spectrum of the signal measured near the bone-conduction speaker is shown as in

Figure 3a. Although the average sound level increased with the amplification of the window, the entire spectrum revealed the same tendency across all frequency bands. The spectrums were used as reference data to calculate the sound level spacing between windows. In

Figure 3b, the response spectrum measured close to the ear canal a had similar tendency as the previous spectrum. A transfer function method was applied to infer the correlation between the reference signal and the spectrum of the signal measured near the ear canal. In this step, the complex frequency response function H was calculated as the ratio between the spectrum of the ear-canal sound pressure and the spectrum of the vibrator acceleration. The normalized frequency response function (n-FRF) was then obtained by dividing the magnitude of H by its maximum value within the analyzed frequency range, so that the maximum magnitude of n-FRF becomes unified. The analysis focuses on the spectral shape rather than on absolute level differences between subjects. The function modified through the correlation was the normalized frequency response function (n-FRF).

Figure 4a shows the n-FRF of a normal subject. Despite the decreased high-frequency band due to energy dissipation of sound by cavity resonance, the level tended to increase as the sound leaked out. In

Figure 4b, none of the features of the normal case appeared in the presence of otitis media.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the utility of vibro-acoustic radiation analysis as a novel, non-invasive diagnostic method for detecting otitis media with effusion (OME). The findings demonstrated that VAR analysis, particularly in the high-frequency range of 8000–10,000 Hz, can effectively differentiate OME from normal middle ear conditions. The proposed diagnostic approach yielded promising results, with an overall classification accuracy of 86.7%, sensitivity of 85.0%, specificity of 80.0%, and an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.986, indicating excellent discriminative power.

One of the most notable findings was the significant difference in VAR signal amplitude between OME and normal ears in the 8–10 kHz frequency range. This suggests that middle ear effusion alters the acoustic properties of the tympanic cavity and ossicular system, specifically affecting the transmission and radiation of vibrational energy at higher frequencies. The 8–10 kHz band sound was associated with the longitudinal resonance of the tympanic cavity predicted by the simplified cavity model in

Section 2.2. The pressure antinode is formed near the tympanic membrane under normal, air-filled conditions. The presence of effusion increases the effective mass and damping of the middle-ear transmission system and partially replaces the air volume with fluid, which is expected to broaden and attenuate this longitudinal cavity resonance and thereby reduce high-frequency sound transmission. Experimental and wideband tympanometry studies have similarly reported that otitis media with effusion shifts middle-ear resonance toward lower frequencies and decreases high-frequency absorbance or energy transmission [

38,

39], consistent with the reduced VAR amplitude observed in the 8–10 kHz band in this study.

In this study, bone-conduction signals amplified in the middle ear and the characteristics of the sound radiated through the tympanic membrane were analyzed to determine the condition of the middle ear. Correlation analysis between the reference sound generated by the bone-conduction speaker and the composite sound measured at the external auditory canal enabled the extraction and exclusion of externally coupled signals (the sound generated from the external ear system or reflected sound from the tympanic membrane). The diagnostic index derived from the extracted responses demonstrated a clear relationship between signal classification and the pathological condition of the middle ear cavity. The physiological basis for these observations lies in the biomechanical changes caused by effusion within the middle ear cavity. The accumulation of fluid increases the effective mass and damping of the system, alters cavity resonance properties, and impairs the mobility of the tympanic membrane and ossicular chain.

Compared to conventional methods, VAR analysis has several practical and clinical advantages. Otoscopy and tympanometry, though widely used, have intrinsic limitations. Otoscopy requires considerable expertise and is inherently subjective. Tympanometry, while objective, often lacks sufficient sensitivity, especially in early-stage OME or when the effusion is minimal. Moreover, wideband tympanometry (WBT), though more informative, is still limited by its dependence on air pressure manipulation and indirect inference of mechanical properties. Recent WBT and wideband absorbance studies have shown that OME was detected accurately based on broadband changes in middle-ear impedance or absorbance [

40] based on air-conduction stimulation through the ear canal. In contrast, VAR proposed in this study does not rely on the pressure modulation or visual interpretation, but rather on quantifiable vibrational–acoustic coupling elicited by the bone-conducted excitation, improving sensitivity. Future work directly comparing VAR with tympanometry and WBT in the same cohort is required to clarify their relative and complementary diagnostic roles.

This study has several limitations. First, the data were collected from a single center with a relatively small number of adult subjects, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations and clinical settings. Larger and more heterogeneous cohorts will be required to validate the robustness of the proposed VAR-based diagnostic index. Second, the middle-ear cavity was modeled using a simplified average adult geometry, without explicitly incorporating patient-specific anatomical variability, such as differences in tympanic cavity volume, geometry, tympanic membrane morphology, or effusion-related changes in stiffness, mass, and damping. As a result, the present model should be regarded as a first-order, group-level approximation intended to facilitate qualitative interpretation of spectral changes rather than a fully personalized predictive model. In addition, the diagnostic index and its threshold were derived from a limited dataset, and extensive cross-validation or external validation was not performed. Consequently, the reported performance metrics, including the high AUC, may be subject to optimistic bias, and the proposed threshold should be interpreted with caution until validated in larger, independent cohorts and directly compared with established diagnostic modalities such as tympanometry and wideband tympanometry. Finally, potential confounding factors, including ear-canal geometry, patient motion, and overlapping acoustic features between different subtypes of otitis media, may have influenced signal quality and classification performance. Future studies incorporating improved motion control, subtype-specific modeling, and more advanced analytical approaches may further enhance diagnostic accuracy.